Entering the zeitgeist as a social media phenomenon and hashtag, the term ‘mansplaining’ is commonly used to capture instances of a man providing an unrequested explanation to a woman in a condescending tone, with the assumption that it is not something with which she is already familiar (Bridges, Reference Bridges2017). Lutzky and Lawson (Reference Lutzky and Lawson2019) revealed the pervasive use of the term mansplaining, highlighting that the neologism was mentioned at least 10,000 unique times on the social media platform Twitter during just a 6-month period spanning 2016 and 2017. This ongoing social conversation begs the question of whether this form of inappropriate behavior or rudeness is similarly prevalent in modern workplaces, and if so, what effect it is having.

Organizational research documents that more covert forms of workplace mistreatment have increased in prevalence (Pearson & Porath, Reference Pearson and Porath2005), which some authors attribute to the condemnation of overt discrimination in the modern Western context (e.g., Cortina, Reference Cortina2008; Kabat-Farr, Settles, & Cortina, Reference Kabat-Farr, Settles and Cortina2020). Indeed, the majority of incidents of mistreatment in a modern workplace are more likely to be behaviors that lack civility or are considered to violate social norms (Andersson & Pearson, Reference Andersson and Pearson1999; Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Magley, & Nelson, Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Magley and Nelson2017), as compared to ones that are overtly discriminatory, hostile, or violent. Acts that include disrespect, condescension, and degradation are particularly effective in harming their target due to the inherent ambiguity surrounding perpetrator intent (Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Magley and Nelson2017; Cortina, Magley, Williams, & Langhout, Reference Cortina, Magley, Williams and Langhout2001).

Rudeness in the workplace is both prevalent and problematic (Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Magley and Nelson2017), yet whether mansplaining is just as pervasive and insidious as other forms of mistreatment remains to be seen. Moreover, we question whether mansplaining is just workplace incivility by another name, or whether it is a distinct concept altogether (see Hershcovis, Reference Hershcovis2011). Advancing research on both mansplaining and incivility requires responses to these questions.

As such, our research endeavors to make four contributions. First, we propose a more comprehensive definition of mansplaining that is grounded in the popular use of the term. We employ this definition to propose a scale for measurement. Second, we establish the extent to which mansplaining is ubiquitous in modern workplaces. Furthermore, we investigate whether men are indeed the typical perpetrators and women the usual targets. Third, we highlight that mansplaining may have deleterious effects by establishing its relationship to several known outcomes of mistreatment (e.g., turnover intentions, emotional exhaustion). Fourth, we explore whether mansplaining is a distinct form of workplace incivility. The results of this research further both our understanding of mansplaining and highlight the importance of including these behaviors in the study and management of workplace mistreatment.

Our research encompasses two studies. First, we qualitatively explore the characteristics and themes of mansplaining through its uses and mentions on Twitter, one of the original venues of the term (Bridges, Reference Bridges2017). We then apply the results of our first study to quantitatively investigate the nature and prevalence of mansplaining in the workplace, including the proposal of a short mansplaining scale, and the possible connection between mansplaining and negative outcomes, as well as its association with incivility. In the following sections, we first provide a brief overview of the concept of mansplaining. We then describe the process and results of our qualitative exploration of mansplaining in Study 1. For Study 2, we first review the literature on mistreatment and incivility, and outline our hypotheses related to mansplaining at work, which are followed by a description of our quantitative methods for investigating the prevalence and correlates of mansplaining, as well as its potential distinctiveness from incivility. Finally, our quantitative results and overall discussion are provided, with implications for researchers and practitioners alike.

Mansplaining

Mansplaining is a portmanteau that combines the words ‘man’ and ‘explain’ (Bridges, Reference Bridges2017). Mansplaining is conventionally understood as an exchange where a man clarifies something to a woman in a condescending tone and with the assumption that the woman does not already know what he is telling her (Bridges, Reference Bridges2017). First popularized in her essay entitled ‘Men Explain Things to Me,’ Solnit (2008/Reference Solnit2014) recounted an instance when a man explained the premise and importance of a book to her. The book in question was in fact Solnit's own – and after her friend's repeated attempts to clarify this to the man by interjecting, ‘That's her book,’ several times, the man eventually appeared to be embarrassed. The mansplaining phenomenon has been characterized by the confidence with which the perpetrator delivers the unrequested message, a tone of condescension, and often involves an interjection, interruption, and a belief that the target has no prior knowledge of the subject (Bridges, Reference Bridges2017).

Women experience mansplaining in a wide variety of fields (Bates, Reference Bates2016). Interestingly, Twitter, the social media platform, has provided extensive evidence of this notion, and is argued to be a key driver of the increased societal discussion of mansplaining (Lutzky & Lawson, Reference Lutzky and Lawson2019). Famously, NASA astronaut Dr. Jessica Meir tweeted about a space-equivalent zone in which water boils instantly, only to have a male Twitter user (with no relevant credentials) attempt to correct her (Bates, Reference Bates2016). Similarly, astrophysicist Dr. Katie Mack's climate change commentary was admonished by a man tweeting a response that she should ‘learn actual science’ (Bates, Reference Bates2016). After Dr. Mack responded that acquiring more than her current credentials – a doctorate in astrophysics – might be ‘overkill,’ the perpetrator asserted that she did not get her money's worth for her degree (Bates, Reference Bates2016).

These accounts are certainly spectacular and raise cause for concern. However, just because there is prominent conversation of a phenomenon does not necessarily entail that it is pervasive. Moreover, even if it is pervasive, it does not necessarily follow that it is harmful. Finally, given that mansplaining is a neologism, it remains to be seen whether our working definitions actually capture how it is being used in the popular lexicon. It is this final unknown that our first study seeks to address.

Study 1: what is mansplaining?

Methods

To more comprehensively explore how the term ‘mansplaining’ is being used in popular discourse, we adopted a qualitative approach. Much discussion of mansplaining has occurred on Twitter, and as such, to solicit a broad range of mansplaining experiences, we built a corpus of data from tweets, scraped from the platform using a Python application (https://pypi.org/project/GetOldTweets3/). After receiving ethics approval and permission to connect to the Twitter API, we developed a Python script to capture English tweets mentioning the term ‘mansplain’ that obtained engagement from other users (i.e., ‘Top Tweets’) published in the 2019 calendar year. This resulted in an initial collection of 2,312 tweets. To preserve anonymity, usernames and identification numbers that are automatically associated with the data were discarded. Because the purpose of our research is to examine mansplaining in the workplace, we used purposive, critical case sampling (Etikan, Musa, & Alkassim, Reference Etikan, Musa and Alkassim2016) to select the 300 tweets most strongly related to the experience of mansplaining at work. These were identified by searching for work-related terms (e.g., coworker, office, boss) or industry specification while reading each tweet that was compiled.

Working with this smaller sample, we conducted a thematic analysis of the data corpus. The first round of coding, performed by one of the authors, built from an established definition of mansplaining (‘a man explaining something to a woman in a tone perceived as condescending’; Bridges, Reference Bridges2017: 94), and further integrated the unsolicited and unwelcome explanation of ‘something one well knows’ from Solnit's (2008/Reference Solnit2014) original description. Using these anchors, tweets were coded as meeting the extant conceptualization for mansplaining if they included these known factors (i.e., unsolicited or unwelcome advice, related to a topic the speaker knows well, provided in a condescending tone), with attention devoted to coding for other aspects (e.g., context, speaker's tone) beyond the extant definition.

The second round of coding was collectively undertaken by three of the authors to confirm the assessment of tweets that fell under the traditional conceptualization of mansplaining and to further consider those that integrated concepts beyond the traditional definition. The intent of this second round of coding was to determine whether there are aspects of mansplaining that the traditional conceptualization has omitted.

Results

As predicted, the three traditional themes of mansplaining were evident in the tweets we collected: (1) unsolicited and unwelcome advice; (2) explanations of a topic or issue one knows well; and (3) condescending and patronizing tones. In addition to the points mentioned above, three additional themes emerged. The tweets we reviewed indicated that mansplaining experiences might also include (4) a ‘mansplainer’ questioning the target's knowledge or expertise; and (5) speaking in an arrogant or overconfident manner, or with persistence after having been rebutted against. A sixth theme reflected the notion that the ‘mansplainer’ was incorrect or mistaken, explaining something to the target incorrectly.

The first theme, unsolicited and unwelcome work advice, was evident in tweets such as:

I'm still sore from the BRUTAL mansplaining of my own research program I received yesterday. Did you guys know the brain only generates rhythms at THREE frequencies?

An epic case of mansplaining today. So happy for his suggestions, ‘that I feel will help both you and the literary industry.’

I won't bore you with the contents of the actual mansplaining but here are some highlights, including ‘you are the wife of someone I respect’. This from a white man who is a distant acquaintance, re: a company I myself founded. I don't need to tell you the advice was unsolicited.

With regards to the second theme, explanations of a well-known topic, tweets such as the following were demonstrative:

Some white guy agent was mansplaining how great the Asian American Writers Workshop is … to me. I had to mention I cofounded the organization + was its board president for 10 years … …he went on to explain what the AAWW does + said I should go to their programs some time

he kept mansplaining my own job to me, even though he works in a completely different field and had no idea what he was talking about

If you are planning on mansplaining something to me maybe pick cars, or sport or something I don't actually know about rather than the field I actually trained and worked in. it'll still piss me off but at least I won't know if you're wrong or not …

Occasionally, the third theme – mentions of condescending and patronizing talk – was identified explicitly, whereas on other occasions, this was implicit.

Some mighty fine #mansplaining here. We love it when men tell us what we should be calling our campaign about women's experiences in the workplace. Apparently our name is ‘stupid’ and we should call ourselves something that evokes more seriousness.

Every woman knows this look. Every woman knows this tone. Every woman knows this condescension. Every woman has experienced this level of mansplaining. On behalf of every woman, thank you Elizabeth Warren. You are one class act. #DemDebate #TeamWarren

Interestingly, a fourth theme of questioning a target's knowledge or expertise emerged from our data, as exemplified in the following:

One of my peer's students sent her an email about their lab report grade mansplaining that scatter plots in research papers don't have error bars ‘This actually happens in research’ so she sent him one of her published papers. What a power move…

Female sports reporter writes a column on mansplaining in sports. Comments from men: ‘Now let me tell you why you're wrong about this.’

Today in mansplaining: man is trying to tell me how to pronounce my own name.

In addition to the patronizing and condescending tones represented by the third theme, a fifth theme described the mansplaining as overconfident, arrogant, or pursued with fervent persistence.

Mansplaining: The intersection of overconfidence & cluelessness where some men get stuck. For men: if you aren't an expert, maybe you don't need to talk. Orgs can help w/ mtg guidelines which allow everyone to talk & facilitators to shut down mansplainers.

when I've pointed out that men are mansplaining to me they just continue mansplaining with even more mansplaining. every time. I've finally realized they don't care at all, even if you're an expert – they're just strutting their peacock plumage & we're supposed to clap

Finally, a cluster of tweets suggested a sixth theme: that some perpetrators will mansplain even though they are explaining the fact or issue incorrectly, with seeming ignorance to their error. This theme revealed itself in tweets from women in both more skilled and less skilled professions.

white dudes!!!! stop mansplaining to baristas in 2020!!! about coffee or anything!! MY GOD Y'ALL ARE ANNOYING – and usually WRONG.

My face when my answer to an attendee gets interrupted by some guy mansplaining to me that a 3D printer isn't capable of what is on its spec sheet. His qualifications? His team had 3DP a bone in plastic this one time. Not that this is ever okay, but I was the invited keynote.

As indicated in some quotes above and in the following, the emotional impact of mansplaining was evident in certain tweets. Frustration, annoyance, and feeling offended were the emotions that targets most commonly expressed in their tweets; culminating in fatigue over time.

I'm tired of mansplaining colleagues who try to take credit or diminish the importance of what I've said in a meeting because they couldn't come up with the ideas themselves. Contrary to popular belief, it is rude, disrespectful, and really doesn't make one look clever.

A further issue that our qualitative analysis revealed is the notion that targets of mansplaining are not always women. For instance:

Gotta roll my eyes when I tell a mathematician what my book is about and then they proceed to lecture me about the topic. I literally wrote the book on the topic! (Like mansplaining, but I'm not a woman. Mathsplaining?)

Additionally, the perpetrators of mansplaining are not exclusively men, as demonstrated by this tweet:

We talk a lot about mansplaining but not nearly enough about the related phenomenon of feminists who've never done sex work lecturing anti-trafficking activists about sex trafficking because they read an article on the topic

Based these themes, we propose an expansion of Bridges' (Reference Bridges2017) definition of mansplaining: providing an unsolicited or unwelcome, condescending or persistent, explanation to someone, either questioning their knowledge or assuming they did not know, regardless of the veracity of the explanation. The mansplainer is most typically a man and the recipient is most typically not a man.

Given the potential for a broader array of perpetrators and targets, it is important to consider whether the phenomenon may be more pervasive than originally conceived, as well as that the term itself may be a misnomer. With this broadened perspective, we proceeded to investigate the prevalence of the six identified mansplaining themes in modern workplace with the purpose of more firmly establishing who is experiencing mansplaining, who is perpetrating mansplaining, and its potential effects on the recipient.

Study 2: mansplaining prevalence, correlates, and association with incivility

Our qualitative findings replicate past research that suggests all employees are potential targets of disrespect, yet women – and especially women of color – are systemically more likely to experience gender-based mistreatment at work (McCord, Joseph, Dhanani, & Beus, Reference McCord, Joseph, Dhanani and Beus2018). Individuals from hegemonically powerful groups are believed to be the most common perpetrators (McDonald & Charlesworth, Reference McDonald and Charlesworth2016; Rospenda, Richman, & Nawyn, Reference Rospenda, Richman and Nawyn1998), implicitly or explicitly exerting their social power (and perhaps even acting upon their prejudices; Cortina, Reference Cortina2008) to police gender role stereotypes through gender-based mistreatment toward their colleagues (Berdahl, Reference Berdahl2007a, Reference Berdahl2007b; Kabat-Farr & Cortina, Reference Kabat-Farr and Cortina2014; Leskinen, Rabelo, & Cortina, Reference Leskinen, Rabelo and Cortina2015). Disrespectful gender-based conduct – or in this case, mansplaining – may therefore be perpetrated by any individual toward any other (as the tweets suggest; see also Fitzgerald & Cortina, Reference Fitzgerald, Cortina, Travis, White, Rutherford, Williams, Cook and Wyche2018), but empirical evidence and theory support that those with lower social and organizational power will be the most common targets and those with higher social and organizational power will be the most common perpetrators. Thus, as an initial investigation of the prevalence of mansplaining at work, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: There will be gender and race differences in mansplaining experience such that (a) women and gender minorities (vs. men) and (b) visible minority (vs. Caucasian) employees will experience significantly higher rates of mansplaining.

Hypothesis 2: (a) Men will not be the only perpetrators of mansplaining, but (b) men (vs. women and gender minorities) will perpetrate mansplaining at higher rates.

Mansplaining as mistreatment

Interpersonal workplace mistreatment is an umbrella term that represents all negative behavior (or failure to engage in positive behavior) directed toward another individual in the workplace that results in psychological and/or physical harm to the target (Cortina & Magley, Reference Cortina and Magley2003; Hershcovis & Bhatnagar, Reference Hershcovis and Bhatnagar2017), and that targets are motivated to avoid (Hershcovis & Barling, Reference Hershcovis and Barling2010). Behaviors subsumed under this construct range in intentionality and severity, from those of low intensity and ambiguous intent, such as incivility, to those of high intensity with clear intent to harm, such as bullying and violence. In the workplace, mistreatment can occur between coworkers, across hierarchical levels, and can be perpetrated by organizational outsiders (e.g., clients, customers, patients), as well (Barling, Dupré, & Kelloway, Reference Barling, Dupré and Kelloway2009).

Meta-analytic findings (e.g., Bowling & Beehr, Reference Bowling and Beehr2006; Hershcovis, Reference Hershcovis2011; Hershcovis & Barling, Reference Hershcovis and Barling2010) indicate that workplace mistreatment is reliably associated with deleterious attitudinal (e.g., reduced job and life satisfaction, affective organizational commitment, self-esteem; increased turnover intentions), behavioral (e.g., increased counterproductive work behavior, withdrawal, absenteeism; reduced job performance), and well-being (e.g., poorer physical health, sleep; increased emotional exhaustion, psychological distress) outcomes. Though harm tends to increase with greater exposure (Hershcovis & Barling, Reference Hershcovis and Barling2010), experiencing mistreatment of any intensity from even a single perpetrator, and in some cases, on merely a single occasion, is sufficient to threaten well-being (Hershcovis, Ogunfowora, Reich, & Christie, Reference Hershcovis, Ogunfowora, Reich and Christie2017).

Socio-evolutionary explanations (Baumeister & Leary, Reference Baumeister and Leary1995; Lind & Tyler, Reference Lind and Tyler1988), theories of interpersonal injustice (Bies, Reference Bies, Greenberg and Cropanzano2001; Bies & Moag, Reference Bies, Moag, Lewicki, Sheppard and Bazerman1986; Folger & Cropanzano, Reference Folger, Cropanzano, Greenberg and Cropanzano2001), and affective events theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, Reference Weiss, Cropanzano, Staw and Cummings1996), have all been provided to support the association between mistreatment and related outcomes. Social feedback of exclusion arising from mistreatment – especially when tied to immutable aspects of one's identity – can lead to a sense of injustice, negative emotions, a shattered sense or hope of inclusion or belongingness, and feelings of being devalued (Buchanan & Settles, Reference Buchanan and Settles2019; Cortina & Magley, Reference Cortina and Magley2009; Dionisi, Barling, & Dupré, Reference Dionisi, Barling and Dupré2012; Hershcovis et al., Reference Hershcovis, Ogunfowora, Reich and Christie2017; Hershcovis & Barling, Reference Hershcovis and Barling2010). Even micro-events, when left unresolved, are daily hassles that can accumulate and wither well-being over time (DeLongis, Folkman, & Lazarus, Reference DeLongis, Folkman and Lazarus1988; Lazarus & Folkman, Reference Lazarus and Folkman1984).

These extensive impacts on the lives and work of mistreatment targets highlight the importance of a complete understanding of mansplaining. If mansplaining is a form of mistreatment, and if mansplaining is found to be present in modern workplaces, then there is strong reason to worry that mansplaining might also carry similar deleterious effects.

Hypothesis 3: Mansplaining experience will be significantly related to individual and work outcomes, such that mansplaining will be positively associated with (a) emotional exhaustion, (b) psychological distress, and (c) turnover intentions, and negatively associated with (d) organizational commitment and (e) job satisfaction.

Mansplaining as incivility?

The rudeness of interactions characterized as mansplaining is arguably self-evident, and given that rudeness is a hallmark of uncivil behavior (Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Magley and Nelson2017), this leads to the consideration of whether mansplaining might be related to incivility. Lay descriptions of mansplaining share many characteristics of incivility, including condescension and belittlement, not listening, disregard for others' opinions, doubting others' judgment, lack of respect, rudeness, insensitivity, and accusations of incompetence (Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Magley, Williams and Langhout2001; Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Leskinen, Huerta, & Magley, Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Leskinen, Huerta and Magley2013; Martin & Hine, Reference Martin and Hine2005; Matthews & Ritter, Reference Matthews and Ritter2016; Porath & Pearson, Reference Porath and Pearson2012). Furthermore, Cortina et al. (Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Leskinen, Huerta and Magley2013) describe workplace incivility as particularly effective due to its ambiguous nature; the ambiguity of intent in instances of incivility prevents targets and onlookers from clearly identifying negative intentions in the perpetrator. Incivility, particularly when it targets women or people of color, can often be falsely attributed to misunderstanding, perpetrator personality, or work-related frustration; rather than discriminatory messages (Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Leskinen, Huerta and Magley2013). Similarly, mansplaining carries the potential for ambiguity: observers and targets could misinterpret mansplaining as an attempt to inform with ostensibly good intentions despite their ingrained biases (Buerkle, Reference Buerkle2019).

Evidence suggests that 96% of employees can expect to experience incivility and up to 99% of employees will witness incivility while at work (Porath & Pearson, Reference Porath and Pearson2010, Reference Porath and Pearson2013). In their recent review, Schilpzand, De Pater, and Erez (Reference Schilpzand, De Pater and Erez2016) highlight a litany of consequences meaningfully associated with incivility, including (but not limited to) negative emotions, emotional exhaustion and burnout, stress and psychological distress, the perpetration of incivility and other forms of mistreatment, counterproductive work behavior, absenteeism and withdrawal from work, intended and actual turnover, as well as reduced organizational commitment, job and life satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior, and job performance (see also Andersson & Pearson, Reference Andersson and Pearson1999; Kabat-Farr, Cortina, & Marchiondo, Reference Kabat-Farr, Cortina and Marchiondo2018; Kabat-Farr, Walsh, & McGonagle, Reference Kabat-Farr, Walsh and McGonagle2019; Lim, Ilies, Koopman, Christoforou, & Arvey, Reference Lim, Ilies, Koopman, Christoforou and Arvey2018; Porath & Pearson, Reference Porath and Pearson2010). Moreover, despite the low intensity of uncivil interactions, the results of daily diary studies suggest that targets who experience workplace incivility during a given workday are more likely to display negative affect and distress at the end of that workday (Park, Fritz, & Jex, Reference Park, Fritz and Jex2018; Zhou, Yan, Che, & Meier, Reference Zhou, Yan, Che and Meier2015). Therefore, given this high prevalence and potential to influence individual and organizational outcomes, incivility poses a potent threat to employee well-being and organizational success (Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Magley and Nelson2017; Porath & Pearson, Reference Porath and Pearson2010).

It is important to reconcile the association between incivility and mansplaining ahead of future research in either area for two key reasons. First, though mansplaining is a neologism, it is not necessarily a novel phenomenon, nor is it beyond the conception of phenomena previously studied in organizational science. There has been a proliferation of workplace mistreatment constructs, many of which overlap to some extent (Hershcovis, Reference Hershcovis2011). Efforts have been made to reconcile these constructs in order to streamline research in the area (e.g., Bowling & Beehr, Reference Bowling and Beehr2006; Hershcovis, Reference Hershcovis2011; Hershcovis & Barling, Reference Hershcovis, Barling, Langan-Fox, Cooper and Klimoski2007; Raver & Barling, Reference Raver, Barling, De Dreu and Gelfand2008). Working from the assumption that there may be overlap between incivility and mansplaining allows us to pre-emptively protect against the jangle fallacy, whereby a single construct of interest is investigated under two or more different names (Johnson, Rosen, & Chang, Reference Johnson, Rosen and Chang2011; Kelley, Reference Kelley1927). Second, if it is found that mansplaining is indeed prevalent and associated with deleterious outcomes, it would be beneficial to provide recommendations to both employees and organizations on how to reduce its incidence and harm. If mansplaining is likewise found to be related to incivility (and selective incivility, in particular), there is a broad base of literature that can be confidently drawn upon to support targets, rather than waiting to engage in more onerous research. Conversely, if mansplaining is found to lack considerable overlap with incivility, relying upon findings from incivility research may not be sufficient, and further research will be needed to more comprehensively understand the phenomenon before targeted recommendations can be offered.

At this time, however, there is reason to believe that mansplaining and incivility may be conceptually related. Operating on this premise, we build on past findings related to incivility (and selective incivility, in particular) to propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4: Mansplaining items will load as a second factor onto an existing incivility scale (i.e., Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Leskinen, Huerta and Magley2013).

Hypothesis 5: Mansplaining will explain a significant proportion of variance in individual and work outcomes beyond that predicted by incivility.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Participants (N = 543) were adult citizens or permanent residents of the United States or Canada who self-reported working at least 20 h per week during the 12 months prior to completing the study. After receiving ethics approval, these participants were recruited through Prolific, an online recruitment tool designed to maximize both research validity and the ethical treatment of participants (Palan & Schitter, Reference Palan and Schitter2018). The first three questions of our study confirmed the recruitment criteria, and participants (n = 43) who did not meet these criteria were directed to return their submissions. Participants who did meet our inclusion criteria first responded to questions about their experiences in their work environment (as further outlined below), followed by demographic information. On average, participants required 12.5 min to complete the survey. Once completed, participants were debriefed, thanked for their time, and paid £1.60 (approximately$2.20 USD or $2.75 CAD). Through data cleaning, we sought to remove responses that demonstrated no variability, including among reverse coded items. One participant's response was removed. The final sample comprised 499 participants.

Men formed the majority of the sample (n = 277; 55.4%), with 215 women (43.0%) and 8 nonbinary and transgender (1.6%) participants also taking part. American participants formed 70.6% of the sample. When asked of their cultural or racial identification, 67.4% of participants self-identified as white, 17.4% as east, south, or south-east Asian, 4.8% as Black, 4.0% as Latin American, and 5.6% as mixed race. The average age of the sample was 32.0 years (SD = 8.44) and their average tenure at their current workplace was 5.5 years (SD = 4.34). The majority of participants (70.4%) had obtained at least a Bachelor's degree, and 87.1% worked full-time (30 h or more per week) during the calendar year of 2019.

Measures

As this study was conducted during the fall of 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we chose to ask participants about their work experiences during the calendar year of 2019. While this had the potential to introduce bias due to errors in memory or insufficient effort being put forth to recall events from the appropriate timeframe (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2012), these concerns were balanced by a desire for participants to consider only routine work experiences. As previous mistreatment scales have been demonstrated to be valid and reliable when asking participants to remember experiences over the previous 2–5 years (e.g., Berdahl & Moore, Reference Berdahl and Moore2006; Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Magley, Williams and Langhout2001, Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Leskinen, Huerta and Magley2013), we considered this recall task to be reasonable.

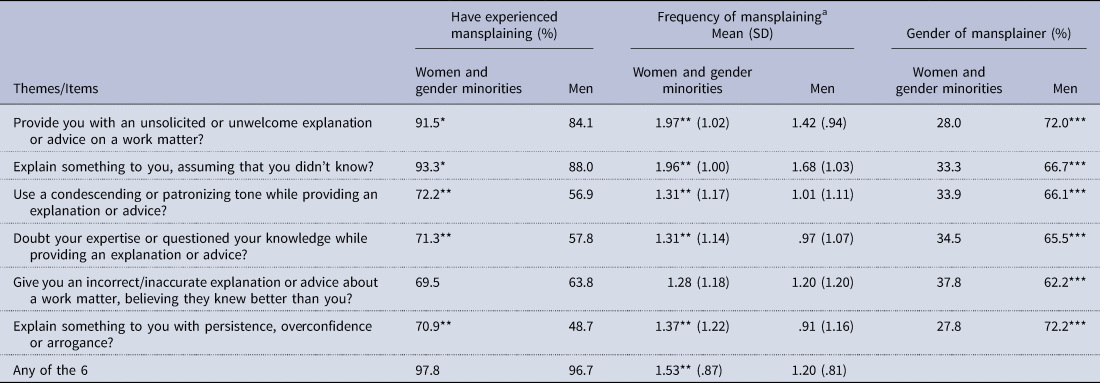

Mansplaining

Based on our identification of six themes of mansplaining identified in Study 1, we developed six associated questions. To address the notion that the perpetrator and target may be of any gender, we ensure that the questions did not reference the gender of either. Implementing the same frequency scale as that from the Workplace Incivility Scale (Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Magley, Williams and Langhout2001, Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Leskinen, Huerta and Magley2013), we conducted a brief pilot test of the items with 10 participants (women, men, and nonbinary individuals with at least 5 years of work experience) to assess its face validity before including the items in our scale (further details available from the authors upon request). The resulting questions (listed in Table 1) asked participants to indicate their frequency of experiencing any of the six items while at work along a scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 4 (Many times). The scale was reliable (α = .86). Further description of this scale's performance is presented in the results section.

Table 1. Prevalence of mansplaining

a Of those reporting mansplaining (1 = once or twice; 4 = often).

*Significantly different at p < .05; **significantly different at p < .01; ***significantly different at p < .001.

Mansplaining context

Participants who indicated having experienced mansplaining during the previous year (i.e., selected a response greater than 0 on any item in the mansplaining scale) were asked follow-up questions. They were asked to think of a specific time when someone directed that behavior towards them and to indicate the gender of the perpetrator.

Outcomes of mistreatment

We used the emotional exhaustion subscale of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (Demerouti, Bakker, Vardakou, & Kantas, Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Vardakou and Kantas2003), finding that the eight items (e.g., ‘There are days when I felt tired before I started work’) performed reliably (α = .82) when participants provided their ratings along the recommended 4-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 4 = Strongly agree).

The 10-item version of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K-10; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Andrews, Colpe, Hiripi, Mroczek, Normand and Zaslavsky2002) was then used to assess psychological distress along a 5-point scale (1 = None of the time to 5 = All of the time) how frequently participants experienced various psychological symptoms (e.g., ‘Did you feel hopeless?’) in a typical month (α = .94).

Organizational commitment (Mowday, Steers, & Porter, Reference Mowday, Steers and Porter1979) was assessed using nine items (e.g., ‘I really care about the fate of this organization’) assessed along a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree), demonstrating a reliability of α = .92.

The three-item Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire (Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins, & Klesh, Reference Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins, Klesh, Seashore, Lawler, Mirvis and Cammann1983) was used to reliably (α = .92) measure job satisfaction (e.g., ‘All in all, I am satisfied with my job’) along a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree).

Kelloway, Gottlieb, and Barham's (Reference Kelloway, Gottlieb and Barham1999) four-item measure investigated participants' turnover intentions (e.g., ‘I am thinking about leaving this organization’) along a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree), and performed reliably (α = .94).

Incivility

Experiences of incivility were measured using Cortina et al.'s (Reference Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Leskinen, Huerta and Magley2013) updated Workplace Incivility Scale, which asks participants to indicate the frequency (0 = Never to 4 = Many times) of experiencing 12 uncivil behaviors (e.g., ‘Gave you hostile looks, stares, or sneers.’). Our final scale comprised nine items demonstrating a reliability of α = .92. Further description of this scale's treatment is presented in the Results section.

Finally, participants responded to demographic questions asking them their age, gender, ethnic or racial identity, highest level of education, and tenure with their employer.

Results

Overall, more than 95% of our respondents reported having experienced at least some form of mansplaining as exemplified by our six themes. Pairwise tests of proportions indicated no significant differences between men vs. women and gender minorities with respect to having experienced any form of mansplaining. However, looking at the six forms of mansplaining individually, men were significantly less likely to report having experienced five of the six forms, as compared to women and gender minorities (see Table 1). There were no significant differences in the sixth form of mansplaining that involved an explanation that is incorrect/inaccurate. Similarly, for those that had experienced each form of mansplaining, men reported significantly lower frequency in the same five of the six forms of mansplaining. As such, hypothesis 1a was partially supported: equal proportions of men and women and gender minorities have experienced mansplaining, but women and gender minorities experience mansplaining at significantly higher frequencies. It should be noted that only eight respondents identified themselves as a gender minority, rendering statistical tests of differences for this as a separate category impractical.

Hypothesis 1b was not supported. There were no significant differences between visible minorities and nonvisible minorities in either experience or frequency of mansplaining across any of the six items.

Men, women, and gender minorities were all reported to be perpetrators of mansplaining (see Table 1). However, binomial tests of proportions for each of the six forms of mansplaining indicated that men were significantly more likely to be reported as the perpetrators. As such, both hypotheses 2a and 2b were supported.

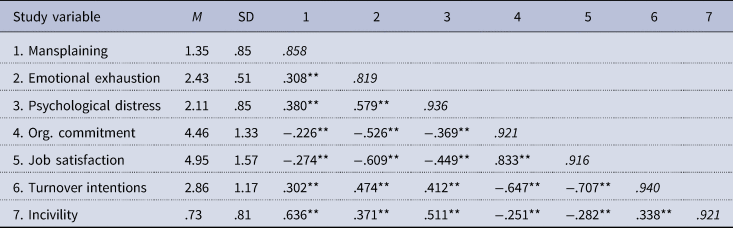

The means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations of our study variables are presented in Table 2. To explore the outcomes associated with mansplaining, we tested the correlations (pairwise Pearson) between each of the six mansplaining items and the five attitudinal and well-being outcomes (see Table 3). Hypothesis 3 was supported. Each of the six mansplaining items was significantly correlated with emotional exhaustion (H3a), psychological distress (H3b), turnover intentions (H3c), organizational commitment (H3d), and job satisfaction (H3e).

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and inter-correlations of study variables (N = 499)

Note: Cronbach's alphas are italicized and presented along the diagonal.

**Significantly different at p < .01.

Table 3. Mansplaining themes correlations with mistreatment

**Significant at p < .01.

To test whether mansplaining represents a second factor of incivility (hypothesis 4), we performed confirmatory factor analysis (Child, Reference Child1990) using structural equation modeling, programmed in IBM SPSS AMOS (version 27), with incivility and mansplaining representing two correlated factors (items in the incivility scale are included in Appendix A). All of the six mansplaining items and the 12 incivility items loaded well onto their respective factors (>.6), but the model exhibited poor fit (χ2 = 538.1, df = 134, CFI = .878, RMSEA = .106, SRMR = .079). Based on modification indices, we covaried the errors on two similar incivility items (items 7 and 11; Hermida, Reference Hermida2015) and removed three other items from the incivility scale that did not load uniquely onto either factor (items 1, 2, and 5 in Appendix A). The resulting model exhibited excellent fit (χ2 = 180.2, df = 88, CFI = .978, RMSEA = .046, SRMR = .037) (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). The standardized parameter estimates for the resulting two factors are included in Appendix A. We compared our hypothesized two-factor model to an alternative one-factor model as well as a two-factor model (incivility and mansplaining) with uncorrelated factors (see Table 4). Our hypothesized two-factor, correlated model provided the best fit (Δχ2 = 411.1, p < .01 and Δχ2 = 260.2, p < .01, respectively) with the factors highly correlated at r = .72.

Table 4. Confirmatory factor analysis

The confirmatory factor analysis of the hypothesized two-factor, correlated model also showed good reliability for both factors, good to borderline convergent validity, but inadequate discriminant validity (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010). The incivility factor had good reliability (CR = .97) and convergent validity (AVE = .57). The mansplaining factor had good reliability (CR = .86) and borderline convergent validity (AVE = .50). The discriminant validity for the model was not adequate (MSV = .51, which is less than AVE = .5), suggesting that there is a non-negligible amount of shared variance between the two factors (Farrell, Reference Farrell2010; Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010).

For the remaining analyses, we aggregated the six mansplaining items into a single mansplaining variable and employed the nine-item incivility scale. We performed linear regressions controlling for age, education, tenure, and visible minority status (step one). We added incivility at the second step, before adding mansplaining to the model during the third step (see Table 5).Footnote 1 In each case, incivility was a significant predictor of the attitudinal and well-being outcomes. In turn, even with incivility in the model, mansplaining was a significant predictor of both job satisfaction (B = −.263, SE = .104) and turnover intentions (B = .153, SE = .076). Thus, mansplaining accounted for a small but statistically significant proportion of the variance in the outcomes beyond that of incivility in the case of both job satisfaction (ΔR 2 = .012, ΔF(1,486) = 6.41, p = .012) and turnover intentions (ΔR 2 = .007, ΔF(1,486) = 4.10, p = .043). Hypothesis 5 was therefore partially supported.

Table 5. Hierarchical regression of mistreatment correlates on demographic predictors, incivility, and mansplaining experience

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Discussion

Based on our qualitative findings, we propose an expansion of Bridges' (Reference Bridges2017) definition of mansplaining: someone (usually a man) providing an unsolicited or unwelcome, condescending or persistent, explanation to someone (usually not a man), either questioning their knowledge or assuming they did not know, regardless of the veracity of the explanation.

Our results also indicate that mansplaining is much more than a social media phenomenon, and in fact permeates beyond the virtual realm to affect employees in their day-to-day work lives. Nearly every individual within our sample, regardless of gender, reported experiencing mansplaining at work at least once during the previous calendar year. Indeed, we found that women, gender minorities, and men alike all experienced mansplaining, and that individuals of all genders perpetrated mansplaining (albeit at different rates). Concurrently, as predicted and as the term itself suggests, men were indeed the most common perpetrators of mansplaining (almost twice as likely), and women and gender minority individuals were the most common targets. More than merely being an interaction whereby a man provides an unwelcome explanation to a woman, however, our qualitative study indicates that mansplaining is more multifaceted. More specifically, we identified six characteristics of mansplaining (unsolicited and unwelcome advice; explaining a topic the target knows well; condescending and patronizing tones; questioning a target's knowledge; speaking with arrogance, overconfidence, or persistence; explaining something incorrectly) that might arise individually or in concert within any given interaction identified as mansplaining. Together, these results suggest that mansplaining is both greater in scope than its name suggests and that it is seemingly ubiquitous in modern workplaces.

Beyond merely occurring in modern workplaces, however, our quantitative analyses suggest that mansplaining affects those who are targeted. That is, each of the types of mansplaining were significantly negatively associated with organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and significantly positively associated with turnover intentions, emotional exhaustion, and psychological distress.

Our analyses further suggest that mansplaining may be a form of incivility. Although mansplaining did not account for significant variance in all of the aforementioned outcomes when controlling for incivility experience, it did explain variance in job satisfaction and turnover intentions beyond that of traditional incivility. It could be that mansplaining is on the less severe side of incivility, leading to dissatisfaction rather than more serious psychological outcomes such as burnout and distress.

Given the gendered origins of the term mansplaining as well as the associated gender differences identified in this study, we checked for similar differences in incivility (ANOVA) but found no significant gender differences. This suggests that mansplaining may represent a type of gendered incivility – a form of rudeness most often experienced by women and gender minorities and most likely to be perpetrated by men.

Implications

These findings lead to several implications. First, it is important that practitioners take note of the fact that mansplaining is not merely a social media phenomenon, but a form of mistreatment that is pervasive in modern workplaces. As our qualitative findings indicate, the experience of mansplaining is associated with negative emotions (at the very least) and leads employees to become tired of such experiences over time. Theory and evidence support that even low-level rudeness, such as a thoughtless act, can escalate to higher intensity mistreatment, such as verbal abuse and violence, perpetrated by either targets or observers of the interaction (e.g., Andersson & Pearson, Reference Andersson and Pearson1999; Ghosh, Dierkes, & Falletta, Reference Ghosh, Dierkes and Falletta2011; Groth & Grandey, Reference Groth and Grandey2012). It is therefore vital to address instances of low-level rudeness, such as mansplaining, to prevent reciprocation and escalation in the form of mistreatment or deviance (directed either toward the perpetrator or the organization, respectively; Pearson and Porath, Reference Pearson and Porath2005).

Fortuitously, there are interventions designed to address uncivil behavior in the workforce that have demonstrated beneficial effects. For instance, the Civility, Respect, and Engagement in the Workplace (CREW) intervention is an empirically supported, facilitator-led training that endeavors to mitigate incivility and encourage civility in the workplace (Leiter, Day, Oore, & Spence Laschinger, Reference Leiter, Day, Oore and Spence Laschinger2012; Leiter, Spence Laschinger, Day, & Oore, Reference Leiter, Spence Laschinger, Day and Oore2011). If, as our research suggests, mansplaining is indeed incivility and rudeness by another name, then this intervention may well serve to address mansplaining in addition to other forms of disrespect. Other more informal interventions might include introducing a civility moderator in workplace meetings (as astutely noted in one of the tweets above), or actively promoting a culture of voice, whereby targets of mistreatment feel comfortable and supported when speaking up (civilly) either to perpetrators or leaders about their experience (Cortina, Cortina, & Cortina, Reference Cortina, Cortina and Cortina2019; Olson-Buchanan, Boswell, & Lee, Reference Olson-Buchanan, Boswell and Lee2019).

That CREW might be used as an intervention to address mansplaining at work, however, leads to several implications for scholars – most importantly, that mansplaining might be a previously unacknowledged (or at the very least, underacknowledged) form of selective incivility. We recommend that future research be conducted to clarify the extent to which incivility and mansplaining overlap and advocate that the streams of research continue. Many authors have strongly advised against further fragmenting the mistreatment literature unnecessarily, citing that this has hindered progress in the past (see Hershcovis, Reference Hershcovis2011 for a discussion). Thus, as our evidence suggests that mansplaining may well be distinct from but highly related to incivility, the two should be investigated simultaneously. Until then, however, as there is evidence for some conceptual overlap between mansplaining and incivility, it may be worth investigating whether adding mansplaining to training addressing civility in the workplace (e.g., CREW) demonstrates additional benefits.

Limitations and future directions

In addition to the research suggested above, certain methodological limitations and select findings from our study suggest several future directions. Most notably, our quantitative study was cross-sectional in nature and therefore precludes causal inference. Past studies (e.g., Park, Fritz, & Jex, Reference Park, Fritz and Jex2018; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Yan, Che and Meier2015) have made beneficial use of daily diary methodologies to investigate the effects of incivility at a more granular level. Including mansplaining in future research investigating mistreatment and its effects longitudinally is thus recommended.

We have provided a starting point for the measurement of mansplaining. Further research can refine and validate our initial scale. Our factor analysis results revealed that there was a fair amount of shared variance between the two latent factors that we have named ‘mansplaining’ and ‘incivility,’ suggesting that these constructs are highly related. This was reinforced in our hierarchical regression analyses, which indicated that mansplaining accounted for only a small, but in some cases statistically significant, amount of variance in the mistreatment correlates, after accounting for incivility. Nevertheless, the mansplaining items on their own were significantly related to the mistreatment correlates, as predicted. Taken together, these findings suggest that mansplaining is an experience related to incivility and is just as common as incivility, but its patterns of prevalence may differ from those of incivility. Thus, as mentioned above, it is important to continue studying mansplaining and incivility jointly, until the similarities and differences in the experiences of these rude behaviors are better understood.

The small number of respondents self-identifying as a gender minority prevented robust tests regarding the prevalence and outcomes of mansplaining particular to this diverse community. Future qualitative or quantitative mansplaining research which endeavors to recruit members of gender minorities would be beneficial. Similarly, we did not find differences in mansplaining prevalence across participant racial groups. Past research supports this finding (e.g., Berdahl & Moore, Reference Berdahl and Moore2006; Raver & Nishii, Reference Raver and Nishii2010), but further suggests that while frequency of mistreatment experiences may not meaningfully differ between ethnic groups, variability regarding the type of mistreatment they experience (perhaps due to cultural stereotypes; Buchanan, Settles, & Woods, Reference Buchanan, Settles and Woods2008), as well as the intensity, has emerged. Interestingly, the tweets we collected indicated that ‘whitesplaining’ (e.g., a Caucasian individual explaining racial injustices to a person of color) is also a phenomenon rather frequently discussed on social media. Considering both mansplaining and whitesplaining within research on selective incivility may add nuance to such investigations.

Finally, our investigation was limited to the targets of mansplaining. As past research suggests that incivility affects observers of incivility in a similar manner (e.g., Miner & Cortina, Reference Miner and Cortina2016), it is possible the same is true with regards to mansplaining, and thus might be considered worthy of future investigation.

Conclusion

More than just a social media phenomenon, our study reveals that mansplaining not only occurs in modern workplaces, but that it is pervasive. Through our qualitative evidence, we provide a multi-dimensional view of the construct. In turn, our quantitative evidence suggests that women are not the only targets of mansplaining nor are men the only perpetrators, and more broadly highlights the detrimental effects mansplaining can have. Our research suggests that mansplaining is distinct from incivility, and may be a gendered form of selective incivility. This requires further research and theorizing. Nevertheless, our research indicates that mansplaining should not be considered a petty grievance, nor merely a passing fad, but rather should be understood as an issue related to selective incivility, whereby individuals are targeted based on their identity and made to feel like they do not belong.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2022.81

Financial support

This work was supported by Mitacs (Canada) through the Mitacs Research Training Award.