Introduction

European colonisation of the Americas had a dramatic impact on the indigenous communities with which it came into contact, nowhere more so than in the case of hunter-gatherers. Southernmost South America had been occupied by hunter-gatherers since the early peopling of continental Patagonia c. 12000 BP, and Tierra del Fuego two millennia later, at a time when the Magellan Strait did not yet exist (Borrero Reference Borrero2001; Martin & Borrero Reference Martin and Borrero2017) (Figure 1). The region has been inhabited by highly mobile societies ever since, but the history of the different indigenous hunter-gatherer groups was profoundly affected by the arrival of Europeans in southern Patagonia during the sixteenth century (Pigafetta Reference Pigafetta1946 [1536]), resulting in significant changes in their lifeways (e.g. Borrero Reference Borrero1991; Martinic Reference Martinic1995).

Figure 1. Map showing southern continental Patagonia (Argentina and Chile), Tierra del Fuego and sites considered throughout the paper.

Intensive European colonisation of the area only began in the nineteenth century. By this time, the Tehuelche-Aonikenk groups of southern continental Patagonia were using horses for hunting. Their main prey was the guanaco (Lama guanicoe), a medium-sized, social camelid (90–120kg) (e.g. Martinic Reference Martinic1995). Meanwhile, the groups inhabiting the northern steppe of Tierra del Fuego, known as the Onas-Selk'nam, still hunted (again mostly guanaco) on foot (e.g. Borrero Reference Borrero2001), while the canoe people who lived in the southern and western channels had a marine-oriented diet comprising sea mammals, birds, fishes and mussels (e.g. Orquera et al. Reference Orquera, Legoupil and Piana2011).

The incorporation of new raw materials—especially glass and stoneware—into the production of traditional artefacts is one of several modifications recorded archaeologically, historically and ethnographically (e.g. Musters Reference Musters1871; Borrero Reference Borrero1991; Martinic Reference Martinic1995; Barbería Reference Barbería1996; Topcic Reference Topcic1998; Aguerre Reference Aguerre2000; Parmigiani et al. Reference Parmigiani, De Angelis and Mansur2013; Charlin et al. Reference Charlin, Augustat and Urban2016). At first glance, this change appears to have happened equally across the whole region. Deeper analysis, however, reveals inter-cultural differences. Our data from the late sixteenth century AD onwards, from both southern continental Patagonia and the island of Tierra del Fuego, show remarkable differences in the type and frequencies of artefacts manufactured from these newly introduced materials. We propose an explanation for the above situation, considering demographic and economic variables related to local indigenous groups.

The incorporation of new raw materials, particularly glass, into the production of traditional artefacts due to European contact is not a phenomenon exclusive to Patagonia; it has been recorded archaeologically in other areas too (Martindale & Jurakic Reference Martindale and Jurakic2015). As such, the information from Patagonia has wider implications in that it may relate to broader geographic trends regarding interactions between hunter-gatherers and capitalist European colonisers during periods of early contact.

Patagonia and the impact of outsiders

The first recorded contact between hunter-gatherer populations and Europeans was by Magellan's crew in 1520 (Pigafetta Reference Pigafetta1946 [1536]). Most encounters for many years after were restricted to the coastal fringe, either through direct contact or through the scavenging of shipwrecked materials (especially in Tierra del Fuego and along the Magellan Strait). Following the failed attempt by the Sarmiento de Gamboa expedition to fortify the Magellan Strait in 1580 (Sarmiento de Gamboa & Desquivel Reference Sarmiento de Gamboa and Desquivel1768), many navigators sailed through this region (e.g. Drake in 1578, Cavendish in 1586, Narborough in 1670, Anson in 1740 and Fitz-Roy in 1834, among others; Cuasnicú Reference Cuasnicú1935). More than 150 years passed before the first European settlements were established in southern Patagonia, with the object of controlling traffic through the strait. Shortly afterwards, settlements, mainly in the form of small forts, were established on the Atlantic coast for military purposes (Ortiz Troncoso Reference Ortiz Troncoso1970; Massone Reference Massone1978; Senatore Reference Senatore2007; De Nigris & Senatore Reference De Nigris and Senatore2011). In Tierra del Fuego, the first settlement—an Anglican mission station—was established later, in 1869 (Stirling Reference Stirling1869).

This pool of ‘first encounters’ affected both coastal and inland groups, as recorded in the chronicles of explorers who travelled throughout the interior of Patagonia during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (e.g. Fitz-Roy Reference Fitz-Roy1839; Darwin Reference Darwin1860; Musters Reference Musters1871; Steffen 1909–Reference Steffen1910). Diseases carried by outsiders radically diminished local hunter-gatherer groups in southern continental Patagonia, and especially in Tierra del Fuego, around the beginning of the twentieth century (Massone Reference Massone1982; Borrero Reference Borrero1991; Guichón Reference Guichón1995; Goñi Reference Goñi, Belardi, Carballo and Espinosa2000; García Guráieb et al. Reference García Guráieb, Goñi and Tessone2015). Although newly introduced diseases spread all over Patagonia, their impact on Tierra del Fuego may have been compounded by the nucleated environment of missions in an island setting. This, in addition to the open killing of indigenous peoples, resulted in a more devastating demographic decline than that recorded on the continent (Martinic Reference Martinic1995; Borrero Reference Borrero2001).

During the nineteenth century, the Argentinian and Chilean governments started to take an economic interest in the region, incorporating Patagonian land into their territories through military campaigns (Bandieri Reference Bandieri2005; Coronato Reference Coronato2010). In order to populate the newly conquered areas, European immigration was encouraged both in continental Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. A sheep-herding economy was promoted, leading to the available land being divided and fenced off. This new system of land use, implemented from around 1880 onwards, was another devastating process for the highly mobile indigenous groups (Borrero Reference Borrero, Burch and Ellanna1994; Barbería Reference Barbería1996).

Although the historical development and tempo of occupation by outsiders may be regarded as similar between the mainland and the island, there were, nevertheless, major differences in its effect on the indigenous groups. In continental Patagonia, the land was divided into ranches (estancias), with indigenous groups either recruited or coerced into semi-sedentary ‘reservations’ (Barbería Reference Barbería1996; Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2010), in a process similar to that which occurred in North America. In Patagonia, this reservation policy was chiefly planned by the Argentinean government. As an alternative strategy, a minority of Tehuelche-Aonikenk people managed to occupy marginal areas, occasionally participating in the new sheep-herding economy (e.g. Nuevo Delaunay Reference Nuevo Delaunay2012, Reference Nuevo Delaunay2015).

In Tierra del Fuego on the other hand, several religious missions (both Salesians in the north and Anglicans in the south of the island) were created in order to evangelise and nucleate indigenous communities, in a similar process to that recorded in New Zealand and Australia (e.g. Middleton Reference Middleton2010). As a consequence, indigenous groups from northern Tierra del Fuego implemented different strategies to avoid contact as a means for dealing with the outsiders’ policies (e.g. Borrero Reference Borrero1991; Horwitz et al. 1993–Reference Horwitz, Borrero and Casiragui1994; Casali Reference Casali2013). These missions lasted until the beginning of the twentieth century. It was during this time that the first ranches were created and open indigenous killings occurred (Borrero Reference Borrero1991), a practice not observed on the mainland. In addition to all of this, the deleterious effects of exposure to alcohol among indigenous groups on both sides of the Magellan Strait should also be mentioned (Martinic Reference Martinic1995).

In this scenario of dramatic change, one of several modifications to the life of indigenous Patagonian groups, recorded archaeologically and historically, was that mobility strategies became more logistically oriented, both on the mainland (Goñi Reference Goñi, Belardi, Carballo and Espinosa2000) and on the island (Borrero Reference Borrero1991). The introduction of the horse (Equus caballus) on the mainland from the seventeenth century (e.g. Outes Reference Outes1915; Palermo Reference Palermo1986; Martinic Reference Martinic1995; Goñi Reference Goñi, Belardi, Carballo and Espinosa2000; Gómez Otero & Moreno Reference Gómez Otero and Moreno2015; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2015), along with the use of new raw materials (mainly the replacement of lithics with glass, stoneware and, later, metal), were among the most frequently recorded changes. Ethnographic records indicate that artefacts manufactured from European raw materials were being used either on an everyday basis, or as trade goods throughout Patagonia (e.g. Lovisato Reference Lovisato1883; Martinic Reference Martinic1995; Borrero & Borella Reference Borrero and Borella2010). The use of glass and stoneware from bottles obtained from shipwrecks, as well as through exchange and commerce, has been identified both archaeologically and ethnographically in the production of traditional instruments such as scrapers and projectile points (e.g. Jackson Squella Reference Jackson Squella1991a & Reference Jackson Squellab, Reference Jackson Squella1999; Manzi Reference Manzi and Otero1996; Nuevo Delaunay Reference Nuevo Delaunay, Morello, Martinic, Prieto and Bahamonde2007, Reference Nuevo Delaunay2012, Reference Nuevo Delaunay2015; Belardi et al. Reference Belardi, Carballo Marina, Nuevo Delaunay and De Angelis2013; Parmigiani et al. Reference Parmigiani, De Angelis and Mansur2013; Saletta Reference Saletta2015; Charlin et al. Reference Charlin, Augustat and Urban2016).

Glass and stoneware in Patagonia

Data were obtained from fieldwork, archaeological literature and the review of chronicles relating to southern continental Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego (Tables 1 & 2) from the late sixteenth to twentieth centuries AD. In most cases, chronological assignation is relative and based on associated archaeological evidence. This is because the scrapers and projectile points that typify most glass assemblages are too small to allow reliable identification of the bottles from which they were sourced. In a few cases, bottle fragments recovered at the sites allow certain diagnostic observations to be made, about neck shape or inscriptions, for example (Belardi et al. Reference Belardi, Carballo Marina, Nuevo Delaunay and De Angelis2013).

Table 1. Scrapers recovered from continental Patagonia (N/D = no data; * = former ‘reservation’ area).

Table 2. Projectile points and scrapers recovered from Tierra del Fuego Island (N/D = no data).

References to scrapers (Figure 2) and projectile points (Figure 3) manufactured mainly from glass, and much less frequently from stoneware, were recorded at 30 sites (Figure 1): 21 in continental Patagonia, and 9 on Tierra del Fuego (Tables 1 & 2). As shown by these data, 96.6 per cent of the samples come from continental Patagonia. Glass artefacts represent 99.2 per cent, while stoneware is seldom used, and is only ever observed on the mainland. It is worth noting that higher overall frequencies were observed at sites of the twentieth century AD. In continental Patagonia, the use of glass and stoneware has been recorded only for scrapers, despite the fact that lithic projectile points are a conspicuous archaeological Late Holocene tool. On Tierra del Fuego, both scrapers and projectile points have been recorded.

Figure 2. Examples of glass scrapers recovered from the site of Puesto Yatel, located on continental Patagonia (number 4 in Figure 1). (Photograph by Amalia Nuevo Delaunay.)

Figure 3. Example of a glass projectile point recovered from an unknown location on Tierra del Fuego (Fonck Museum collection, Valparaiso, Chile). (Photograph by Fernanda Kangiser.)

Although reports do not always give the detailed techno-morphological characteristics of the instruments, some general trends may nevertheless be outlined from the extant information (Tables 1 & 2). Glass and stoneware scrapers and glass projectile points are morphologically similar to lithic ones (Nuevo Delaunay Reference Nuevo Delaunay, Morello, Martinic, Prieto and Bahamonde2007, Reference Nuevo Delaunay2012, Reference Nuevo Delaunay2015; De Angelis Reference De Angelis, Salemme, Santiago, Piana, Vázquez and Mansur2009; Belardi et al. Reference Belardi, Carballo Marina, Nuevo Delaunay and De Angelis2013). In nearly 48 per cent of the sites where glass-scraper technology has been recorded in continental Patagonia, fragments of the bottles used as raw materials (mostly tall cylindrical bottles) are also recorded, as well as scraper blanks and edge-sharpening and re-sharpening flakes. This suggests in situ manufacturing, as recorded ethnographically (Gómez Otero Reference Gómez Otero1987). The most commonly used part of the bottle is the main body (close to 90 per cent of cases), although bottle bases, shoulders and necks were also exploited. Variation in scraper length is usually between 15 and 56mm, while the width usually measures between 18 and 55mm. Size variation is explained by continued edge resharpening due to the high rate of wear suffered by glass. This appears to be confirmed by the presence of edge-resharpening flakes in some assemblages. Variation of thickness for scrapers is generally between 3 and 30mm (on average 5mm), depending on the type and section of the bottle used. Finally, scrapers are retouched mainly on frontal-lateral edges, followed by frontal, peripheral and lateral edges.

Discussion and final remarks

The introduction of European raw materials (mainly glass, but also stoneware), alongside or as a replacement for local lithic materials, to be used for the production of traditional artefacts such as scrapers and projectile points is one of many consequences of European colonisation on the indigenous communities of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego.

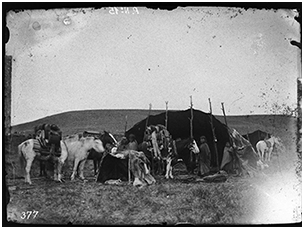

According to ethnographical and historical records, glass scrapers were used to process hides, an activity typically associated with women (e.g. Musters Reference Musters1871; Aguerre Reference Aguerre2000). This use has been corroborated by use-wear analysis on archaeological and experimental scrapers (Belardi et al. Reference Belardi, Carballo Marina, Nuevo Delaunay and De Angelis2013). Processed hides were used to manufacture cloaks—quillangos—and large tents—toldos—in continental Patagonia (Figure 4), and cloaks and wind breakers in Tierra del Fuego. Cloaks and shelter tents were manufactured mainly from guanaco hide, although the use of other hides (e.g. fox, puma, rodents, Darwin's rhea—a flightless bird—cow and horse) has also been recorded (Musters Reference Musters1871; Gusinde Reference Gusinde1951; Martinic Reference Martinic1995; Prieto Reference Prieto, McEwan, Borrero and Prieto1997; Casamiquela Reference Casamiquela2000; Caviglia Reference Caviglia2002). The re-use of sailcloth or burlap has also been recorded for toldos during the early and middle twentieth century (e.g. Casamiquela Reference Casamiquela2000; Halvorsen Reference Halvorsen2011). One major difference between the two areas relates to the fashion in which the cloaks were worn, and may attest to the level of labour invested in hide treatment. In continental Patagonia the fur was usually worn on the inside, while complex decorations were generally displayed on the scraped side (e.g. Casamiquela et al. Reference Casamiquela, Martinic, Mondelo and Perea1991; Caviglia Reference Caviglia2002). In Tierra del Fuego, on the other hand, cloaks were generally worn with the fur on the outside, and were left undecorated on the scraped side (e.g. Spears Reference Spears1895; Gallardo Reference Gallardo1910; Gusinde Reference Gusinde1951). Although there is no accepted explanation for this difference, variation in climatic conditions is generally acknowledged as a probable factor (e.g. Musters Reference Musters1871: 161; Gallardo Reference Gallardo1910: 104; Lothrop Reference Lothrop1928: 53; Gusinde Reference Gusinde1951: 177–78). Furthermore, processed hides were an important trade good between indigenous groups and Europeans for export from continental southern Patagonia during the nineteenth century (e.g. Martinic Reference Martinic1995; Topcic Reference Topcic1998). Glass projectile points were used for hunting on an everyday basis and were also valuable as souvenirs, and thus became important as trade goods themselves (Lovisato Reference Lovisato1883: 195), as evidenced by several ethnographic collections in museums in both America and Europe (Charlin et al. Reference Charlin, Augustat and Urban2016).

Figure 4. Photograph showing examples of toldos (large tents) and quillangos (cloaks) in continental Patagonia c. AD 1900. Reproduced from Proyecto Allen under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 unported (CC-BY-SA 3.0) licence. Available at: http://bit.ly/2q0bLIE (accessed 26 May 2017).

Data gathered and presented in this paper show important differences between artefactual glass and stoneware samples from continental Patagonia and the island of Tierra del Fuego, especially in the frequencies with which they are encountered archaeologically (Tables 1 & 2). In order to understand these differences, the distinctive historical trajectories of the two areas rooted in the context of their particular demographic and economic variables must be considered.

In continental Patagonia, land division into ranches from the nineteenth century onwards led to most of the local groups inhabiting the region being recruited as labourers, or coerced into semi-sedentary ‘reservations’. Within the ‘reservations’, groups were able to maintain traditional aspects of everyday life such as semi-nomadism—although within a far more restricted territory (Barbería Reference Barbería1996)—including the use of toldos (e.g. Aguerre Reference Aguerre2000). The latter were recorded in some places as late as the 1960s (Halvorsen Reference Halvorsen2011). Another important factor was the introduction of the horse into daily life and its role as facilitator for guanaco hunting, not only for hide procurement, but also as a source of hide itself. In addition to this, the horse played a key role in the progressive abandonment of projectile points for hunting, as lithic bolas came to be used more frequently (Outes Reference Outes1915; Vecchi Reference Vecchi2010; Nuevo Delaunay Reference Nuevo Delaunay, Zangrando and Barberena2013).

In Tierra del Fuego, by contrast, most of the indigenous inhabitants, and especially the Onas-Selk'nam peoples, were relocated into missions (Borrero Reference Borrero1991), thereby enforcing a more direct control over lifeways, and making it more difficult for them to sustain most of their traditional customs openly. It is worth mentioning that although the use of bolas has also been recorded here, this differed from the way in which they were used by hunters mounted on horseback on the mainland (e.g. Torres & Morello Reference Torres, Morello, Borrero and Borrazzo2011).

It appears that the higher frequencies of glass scrapers recorded in southern continental Patagonia as compared to Tierra del Fuego are related to the higher incidence of guanaco hide use (large toldos and cloaks) in the former area. The scrapers were associated with the processing of guanaco hides, both for manufacturing toldos and cloaks, and for sale and exportation in a market economy (e.g. Topcic Reference Topcic1998). The hunting of guanaco, in turn, was probably greatly enhanced by the introduction of the horse, which played a key role in the progressive abandonment of projectile points on the mainland, just as its absence played a role in the persistence of projectile points on Tierra del Fuego. Additionally, the trading of hides was more important in the economies of groups located north of the Magellan Strait. A higher human population and the lack of bio-geographic barriers on the mainland were also key elements differentiating the trajectories seen on the island and the mainland. Tehuelche-Aonikenk societies, although highly affected by European contact, managed to endure with greater resilience than the more isolated islanders. Moreover, the ‘reservations’ may have been more ‘permissive’ than missions on Tierra del Fuego, perhaps because they were partly negotiated by indigenous groups (Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2010). These factors may explain why traditional Tehuelche-Aonikenk ‘know-how’ persisted longer than that of their southern neighbours, an inference which is further supported by the higher overall frequencies of glass scrapers recorded in the twentieth century.

The scenario discussed here presents contrasting contexts for the use of new raw materials by hunter-gatherer groups due to European contact within two distinct geographic areas of southern Patagonia: the mainland and the island of Tierra del Fuego. The differences were underpinned by a number of key factors interacting with one another to varying extents: the introduction of the horse on the mainland but not on the island; the integration of commercial networks based on local resources such as guanaco into a newly imposed capitalist economic framework; different demographic patterns; bio-geographic barriers; and the establishment of ‘reservations’ and missions. The resulting archaeological landscape pattern that arises is diverse, depicting a heterogeneous scenario for Patagonia during historical times. Finally, considering that the use of introduced European raw materials to manufacture traditional instruments is not a phenomenon exclusive to Patagonia, the data presented herein has wider implications in that they reveal the various ways in which hunter-gatherers coped with culture contact.

Acknowledgements

We thank Luis Borrero, Adolfo Gil, César Méndez and Gustavo Martínez for comments on previous versions of this work, and Rafael Goñi, Mark MacGranaghan, Elisa Figueroa Cox and Fernanda Kangiser (Museo Fonck, Valparaíso, Chile) and Sergio Raggi (Ea. La Margarita). Peter Mitchell and Alistair Paterson made valuable comments that helped to improve this manuscript. Thanks also go to the UNPA (PI 29/A360-1, PI 29/A304-1), PIP/CONICET N° 11220120100406, UBACYT N° 20020130100293BA and the Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación-INAPL.