Introduction

Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) can first emerge during pre-adolescent years, with a mean age of OCD onset reported as 10.5 years in paediatric populations (Geller et al., Reference Geller, Biederman, Jones, Park, Schwartz, Shapiro and Coffey1998a; Geller et al., Reference Geller, Biederman, Jones, Shapiro, Schwartz and Park1998b; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Geller, Jenike, Pauls, Shaw, Mullin and Faraone2004), and is associated with substantial impairment to the child’s home, school and leisure time (Piacentini et al., Reference Piacentini, Bergman, Keller and McCracken2003; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Hu, Leung, Chan, Hezel, Lin, Belschner, Walsh, Geller and Pauls2017). Younger onset of OCD is associated with a more chronic course (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Geller, Jenike, Pauls, Shaw, Mullin and Faraone2004); however, the sooner that treatment is provided, the better the outcomes (Mancebo et al., Reference Mancebo, Boisseau, Garnaat, Eisen, Greenberg, Sibrava, Stout and Rasmussen2014) – highlighting the need for timely access to evidence-based treatment for pre-adolescent children with OCD.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) including exposure and response prevention (ERP) is an effective, gold standard psychological treatment for pre-adolescent children with OCD (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Garcia, Coyne, Ale, Przeworski, Himle and Leonard2008; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Sapyta, Garcia, Compton, Khanna, Flessner and Franklin2014; Ivarsson et al., Reference Ivarsson, Skarphedinsson, Kornør, Axelsdottir, Biedilæ, Heyman, Asbahr, Thomsen, Fineberg and March2015; McGuire et al., Reference McGuire, Piacentini, Lewin, Brennan, Murphy and Storch2015; National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2005; Öst et al., Reference Öst, Riise, Wergeland, Hansen and Kvale2016; Paediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team, 2004). Despite this, existing CBT treatments for pre-adolescent children with OCD typically consist of at least 10 hours of therapist support (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Farrell, Pina, Peris and Piacentini2008; Franklin et al., Reference Franklin, Kratz, Freeman, Ivarsson, Heyman, Sookman, McKay, Storch and March2015). Briefer treatments could bring potential to increase the number of children who can benefit from this treatment, particularly given the lack of mental health professionals who are sufficiently trained to deliver CBT treatments (Baker and Waite, Reference Baker and Waite2020; Stallard et al., Reference Stallard, Udwin, Goddard and Hibbert2007). Indeed, Chessell et al. (Reference Chessell, Harvey, Halldorsson, Farrington and Creswell2023) highlighted the ‘battle’ that parents describe in trying to access CBT treatment for pre-adolescent children with OCD.

Brief, parent-led treatments have been used to increase access to treatments for pre-adolescent children with anxiety difficulties and behavioural problems (Ludlow et al., Reference Ludlow, Hurn and Lansdell2020) and may be a potential way to increase access to CBT for pre-adolescent children with OCD. Brief, parent-led treatments involve a therapist working directly with a parent to empower them to apply CBT-based strategies at home with their child (Creswell et al., Reference Creswell, Violato, Fairbanks, White, Parkinson, Abitabile, Leidi and Cooper2017) and can increase access to treatments as, although this approach still requires access to a therapist, parent-led treatments can be delivered briefly and cost-effectively (e.g. Creswell et al., Reference Creswell, Violato, Fairbanks, White, Parkinson, Abitabile, Leidi and Cooper2017) with good outcomes achieved when delivered by non-specialist therapists (Thirlwall et al., Reference Thirlwall, Cooper, Karalus, Voysey, Willetts and Creswell2013). Delivering treatment via parents may also be particularly advantageous for this population, given that pre-adolescent children are more dependent on their parents than adolescents (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Garcia, Fucci, Karitani, Miller and Leonard2003) and parents of pre-adolescent children with OCD frequently report challenges not knowing how to help or respond to their child’s difficulties (Chessell et al., Reference Chessell, Harvey, Halldorsson, Farrington and Creswell2023).

To date, limited research has explored the potential for parent-led treatments to increase access to CBT for pre-adolescent children with OCD. Exceptions to this include Lebowitz (Reference Lebowitz2013) and Rosa-Alcázar et al. (Reference Rosa-Alcázar, Iniesta-Sepúlveda, Storch, Rosa-Alcázar, Parada-Navas and Olivares Rodríguez2017, Reference Rosa-Alcázar, Rosa-Alcázar, Olivares-Olivares, Parada-Navas, Rosa-Alcázar and Sánchez-Meca2019). Lebowitz (Reference Lebowitz2013) examined the preliminary efficacy of a 10-hour parent-led intervention specifically designed to reduce family accommodation among parents of children and adolescents (aged 10–13 years old) with OCD, and Rosa-Alcázar et al. (Reference Rosa-Alcázar, Iniesta-Sepúlveda, Storch, Rosa-Alcázar, Parada-Navas and Olivares Rodríguez2017, Reference Rosa-Alcázar, Rosa-Alcázar, Olivares-Olivares, Parada-Navas, Rosa-Alcázar and Sánchez-Meca2019) examined the efficacy of 12 hours of parent-led CBT for very young children (aged 5–7 years old) with OCD. Despite significant improvements in children’s OCD severity in these studies, these treatments consisted of at least 10 hours of individual support, often with specialist therapists, limiting the potential widespread dissemination of these treatments in routine clinical services where resources are often limited. Thus, there is a need to develop and evaluate a brief, parent-led CBT treatment that can be delivered by non-specialist therapists to provide a cost-effective way to increase access to treatments for pre-adolescent children with OCD and that is acceptable to parents.

The current study is a preliminary evaluation of a brief, parent-led CBT treatment for pre-adolescent children with OCD using a non-concurrent, multiple baseline approach. The treatment was adapted from an existing, evidence-based parent-led CBT treatment for pre-adolescent children with anxiety disorders (Thirlwall et al., Reference Thirlwall, Cooper, Karalus, Voysey, Willetts and Creswell2013) and themes identified from recent qualitative work on the experiences of parents of pre-adolescent children with OCD (Chessell et al., Reference Chessell, Harvey, Halldorsson, Farrington and Creswell2023). This included the need for guidance to be sensitive to the challenges and emotional difficulties that parents experience, and the need to provide clear, manageable advice to parents on how they should respond to their children’s OCD to reduce parental helplessness and to empower parents in their ability to support their children. Specifically, this study aimed to examine: (1) the clinical outcomes for children whose parents participated in a brief, parent-led CBT treatment, and (2) acceptability of the treatment to parents.

Method

This article is written in accordance with the recommended reporting guidelines for multiple baseline approaches (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Perdices, Rosenkoetter, Shadish, Vohra, Barlow, Horner, Kazdin, Kratochwill and McDonald2016).

Study design

A non-concurrent multiple baseline approach was used to evaluate the treatment as this is appropriate when evaluating novel treatments with clinical populations (Horner et al., Reference Horner, Carr, Halle, McGee, Odom and Wolery2005; Watson and Workman, Reference Watson and Workman1981). In line with previous case series research (e.g. Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Oar, Waters, McConnell, Tiralongo, Garbharran and Ollendick2016; Ollendick et al., Reference Ollendick, Muskett, Radtke and Smith2021), we aimed to recruit approximately 10 families to participate in this study. A series of AB replications were conducted across participants and consisted of a no-treatment baseline phase (A) and a treatment phase (B). Families were randomly allocated (using block randomisation) to one of three pre-determined baseline lengths of 3, 4 or 5 weeks to control for the confound of time (Kratochwill and Levin, Reference Kratochwill and Levin2010). Treatment commenced immediately after the baseline phase.

Participants

Children were required to be UK residents, aged 5–12 years old, and meet DSM-5 criteria for OCD as assessed using the Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule-Parent Report (ADIS-P). Children were excluded if: (1) they were currently receiving a psychological intervention for any mental health difficulty, (2) they were receiving psychotropic medication and the dose had not been stable for at least 2 months, (3) they had a confirmed autism diagnosis, were suspected to have autism (indicated by a score of ≥15 on the Social Communication Questionnaire, SCQ), or had a profound learning disability, and/or (4) there were significant safety concerns that were paramount and would interfere with treatment delivery (i.e. suicidal ideation, recurrent/potentially life-limiting self-harm, or if the child had a child protection plan/was on the child protection register). Parents needed to be UK residents and were excluded if they had a significant intellectual impairment or were unable to understand written English.

Procedure

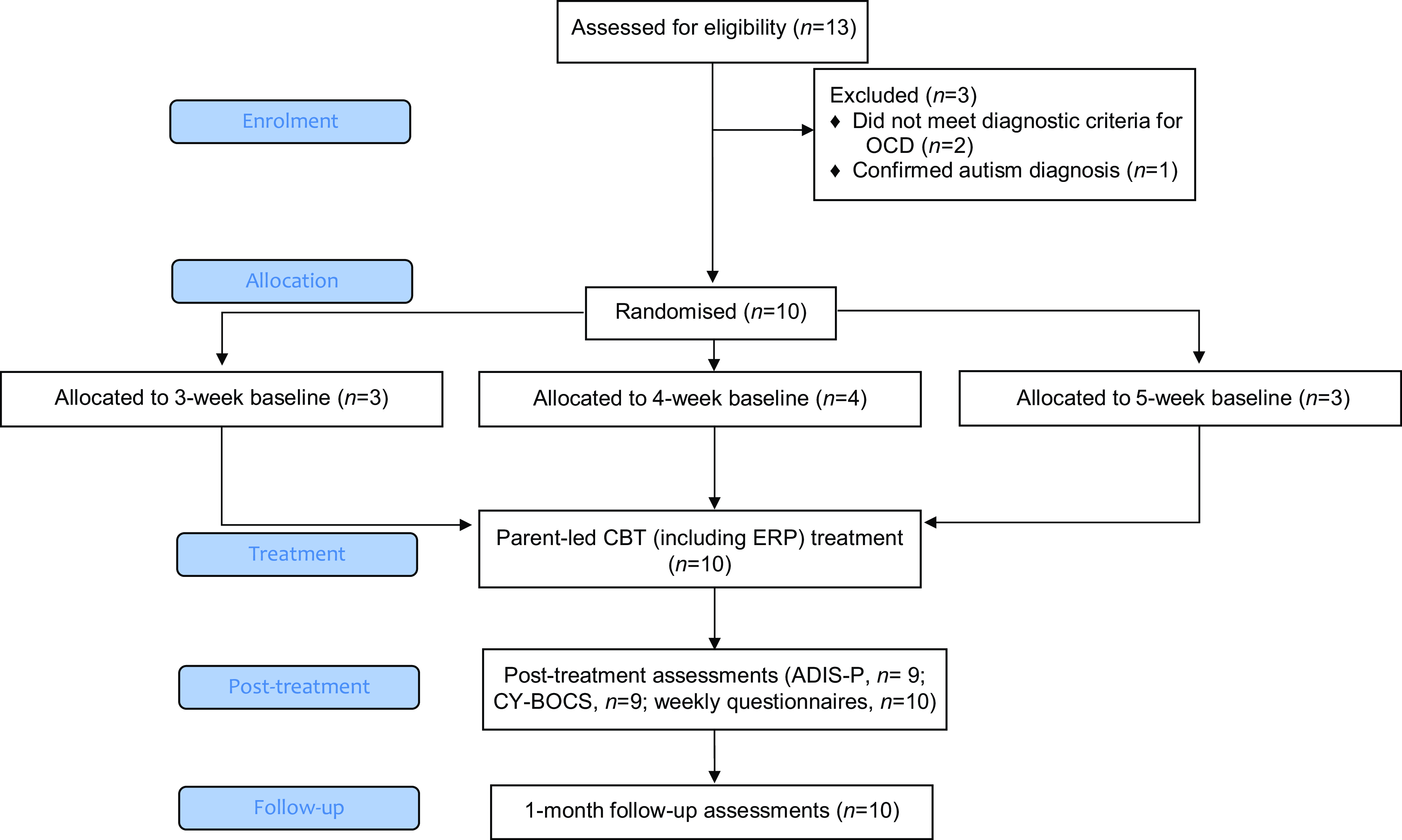

Potential participants were recruited from a local Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) in South-East England (n=2) and advertisements distributed via social media and mental health charities (n=11). Thirteen families were assessed for eligibility; ten families were included in the study and three families were excluded (see Fig. 1). Study procedures are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 1. Flow of participants.

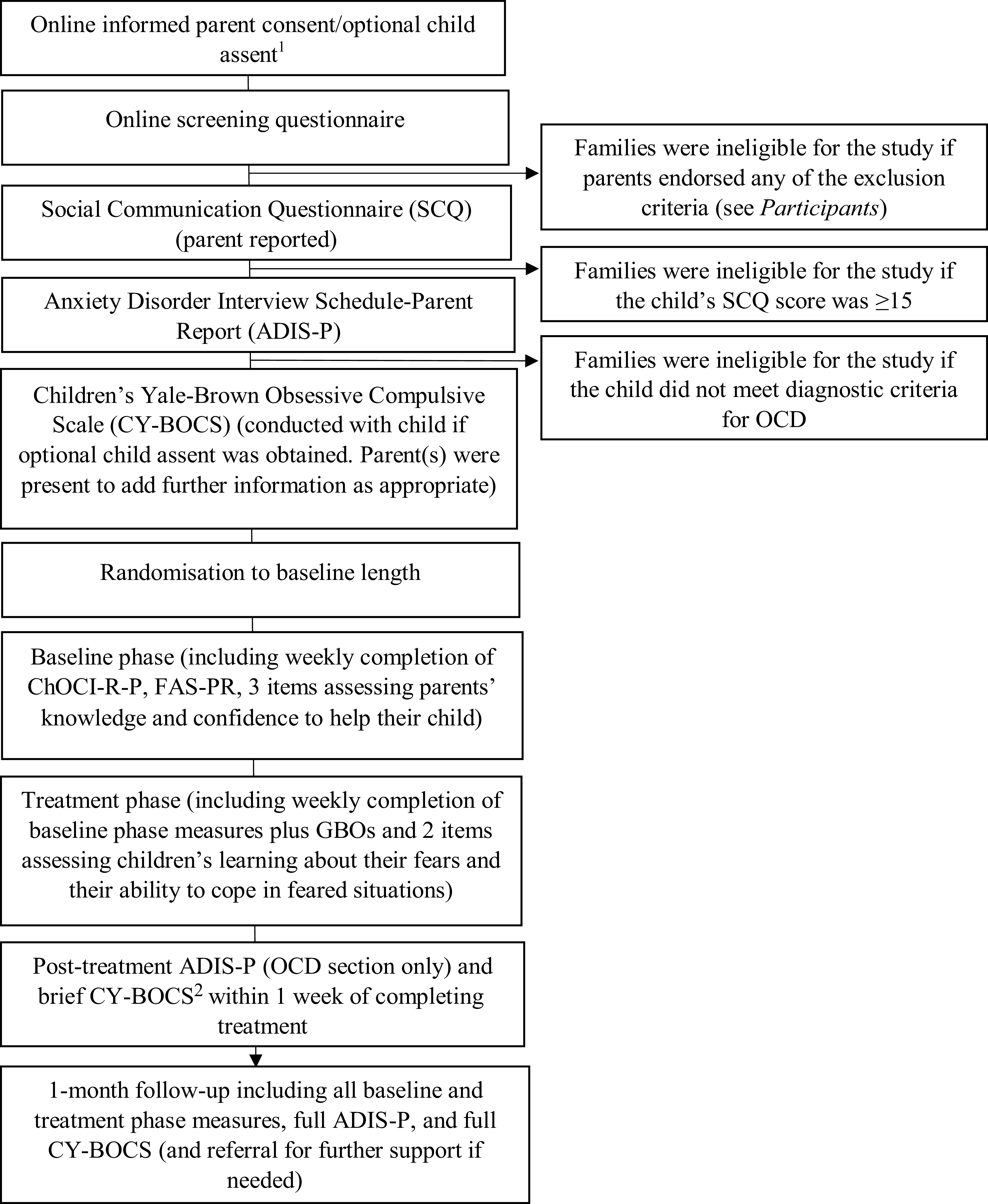

Figure 2. Study procedures. Note. ChOCI-R-P, Children’s Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Revised-Parent Report; FAS-PR, Family Accommodation Scale-Parent Report; GBOs, goal-based outcomes. 1Informed consent was required from all parents who attended at least one assessment and/or treatment session. Child assent was optional; parents were provided with written/audio materials to explain the study to their child and seek optional assent for their child to participate in relevant diagnostic interviews. If child assent was not obtained, diagnostic interviews were completed with parents only. 2The brief CY-BOCS included a review of pre-treatment symptoms, identification of any new symptoms, and completion of post-treatment severity ratings.

Treatment

The treatment was adapted from an existing parent-led CBT treatment for children with anxiety disorders (Creswell and Willetts, Reference Creswell and Willetts2019; Halldorsson et al., Reference Halldorsson, Elliott, Chessell, Willetts and Creswell2019; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Reardon, Taylor and Creswell2022b) to ensure suitability for children with OCD (see Table S1 for treatment adaptations and Table S2 for treatment content in the Supplementary material). The treatment emphasised a step-by-step ERP approach (i.e. where children are gradually exposed to their obsessions, whilst refraining from performing their compulsions; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Thamrin, Pérez, Peris, Storch and McGuire2020) with a focus on helping children to learn new information about their fears/worries/obsessions and their ability to cope in feared situations without performing compulsions (Craske et al., Reference Craske, Treanor, Conway, Zbozinek and Vervliet2014). Parents were offered six to eight individual treatment sessions: four videocall sessions each lasting 1 hour, and two to four shorter telephone/videocall review sessions (mode dependent on parent preference) each lasting 30 minutes (totalling 5–6 hours of therapist input per family). Sessions 1–6 were typically delivered weekly and the remaining two sessions (if needed, based on parent-reported weekly treatment measures and a collaborative discussion with participating parents) were delivered over a 2- to 6-week period (based on clinical judgement and families’ preferences). Parents had information to read prior to six of the treatment sessions and completed between-session tasks with their child. Treatment was delivered by a qualified Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner (PWP graduate psychological therapist; C.Ch.) with experience of delivering parent-led CBT for child anxiety disorders.

Measures

Screening measures

Screening questionnaire

Parents completed a screening questionnaire to determine their potential eligibility for the study (see Supplementary material, section 3).

Social Communication Questionnaire-Lifetime Version (SQC; Rutter et al., Reference Rutter, Bailey and Lord2003)

The SCQ is a 40-item parent-report screening measure for autism and has good psychometric properties (Berument et al., Reference Berument, Rutter, Lord, Pickles and Bailey1999). Individuals who score ≥15 may have autism and further assessment is recommended (Berument et al., Reference Berument, Rutter, Lord, Pickles and Bailey1999).

Diagnostic outcome measures

Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule-Parent Report (ADIS-P; Silverman, Reference Silverman1996)

The ADIS-P is a semi-structured interview assessing DSM-IV anxiety, mood, and externalising disorders in children and adolescents. The ADIS-P was adjusted to align with the DSM-5 and clinician severity ratings (CSRs) were allocated from 0 to 8 for each diagnosis (with a CSR of ≥4 indicating diagnostic criteria had been met). C.Ch. administered all ADIS-P assessments which were discussed with C.Cr. (a clinical psychologist with extensive experience with the ADIS-C/P). C.Cr./C.Ch. independently assigned diagnoses and CSRs prior to reaching consensus ratings (Creswell et al., Reference Creswell, Nauta, Hudson, March, Reardon, Arendt, Bodden, Cobham, Donovan, Halldorsson, In-Albon, Ishikawa, Johnsen, Jolstedt, de Jong, Kreuze, Mobach, Rapee, Spence, Thastum, Utens, Vigerland, Wergeland, Essau, Albano, Chu, Khanna, Silverman and Kendall2021). The ADIS-P has good test–re-test reliability (Silverman et al., Reference Silverman, Saavedra and Pina2001), concurrent validity (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Piacentini, Bergman, McCracken and Barrios2002), and is sensitive to treatment change (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Healy-Farrell and March2004). Percentage agreement on the presence or absence of diagnoses was 94.4% and inter-rater reliability for CSRs was moderate to good (κ=0.7; ICC=0.9).

Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS; Scahill et al., Reference Scahill, Riddle, McSwiggin-Hardin, Ort, King, Goodman, Cicchetti and Leckman1997)

The CY-BOCS is a semi-structured, clinician-administered measure assessing children and adolescent’s OCD severity. The CY-BOCS is considered the ‘gold standard’ assessment for OCD in young people (Lewin and Piacentini, Reference Lewin and Piacentini2010) and is routinely used in OCD treatment trials (e.g. Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Williams, Perrin, Atkinson, Gallop, Waite and Salkovskis2011; Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, de Diaz, Mathieu, McKenzie, Miyamoto, Donovan, Waters, Bothma, Kroon, Simcock, Ware, Selles, Storch and Ollendick2022; Melin et al., Reference Melin, Skarphedinsson, Thomsen, Weidle, Torp, Valderhaug, Højgaard, Hybel, Nissen, Jensen, Dahl, Skärsäter, Haugland and Ivarsson2020) and was therefore selected as the primary outcome measure for this study. Obsession and compulsion severity are each measured using five scales: (1) time consumed, (2) interference caused, (3) level of distress experienced, (4) effort to resist, and (5) extent of control. Total scores range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater severity. C.Ch. administered all CY-BOCS assessments which were discussed with S.W. (a clinical psychologist with extensive experience with the CY-BOCS). C.Ch./S.W. independently assigned ratings for each scale prior to reaching consensus ratings. The CY-BOCS has good test–re-rest reliability (Storch et al., Reference Storch, Murphy, Geffken, Soto, Sajid, Allen, Roberti, Killiany and Goodman2004), convergent and divergent validity (Scahill et al., Reference Scahill, Riddle, McSwiggin-Hardin, Ort, King, Goodman, Cicchetti and Leckman1997) and can reflect treatment change (Scahill et al., Reference Scahill, Riddle, McSwiggin-Hardin, Ort, King, Goodman, Cicchetti and Leckman1997). Inter-rater reliability across all assessments was excellent (ICC=1.0).

Weekly baseline and treatment phase measures

Children’s Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Revised-Parent Report (ChOCI-R-P; Uher et al., Reference Uher, Heyman, Turner and Shafran2008)

The ChOCI-R-P is a questionnaire measuring the presence and severity of children and adolescents’ obsessions and compulsions. Twenty items assess symptom presence (producing a total symptom score out of 40) and 12 items assess symptom severity (producing a total impairment score out of 48). Higher scores indicate greater OCD symptoms/impairment and a total impairment score >17 has shown sufficient sensitivity to indicate an OCD diagnosis on the ChOCI (Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Frampton, Heyman, Reynolds, Teachman and Rachman2003). The ChOCI-R-P has been shown to have good internal consistency and convergent validity with the CY-BOCS (Uher et al., Reference Uher, Heyman, Turner and Shafran2008) and is sensitive to treatment change (Aspvall et al., Reference Aspvall, Andrén, Lenhard, Andersson, Mataix-Cols and Serlachius2018).

Family Accommodation Scale-Parent Report (FAS-PR; Flessner et al., Reference Flessner, Sapyta, Garcia, Freeman, Franklin, Foa and March2011)

The FAS-PR is a 12-item questionnaire measuring the frequency and severity of parental accommodation of OCD over the past month and has good psychometric properties (Flessner et al., Reference Flessner, Sapyta, Garcia, Freeman, Franklin, Foa and March2011). To ensure suitability for weekly administration, we adapted the frequency of accommodation items (i.e. 0, never; 1, one or two times per week; 2, three to six times per week; 3, daily) producing a total score out of 43.

Items assessing parents’ knowledge and confidence to help their child to overcome OCD

Parents completed three items (each using a 5-point scale) each week to assess the effects of the parent-led intervention on parents’ knowledge and confidence to help their child to overcome OCD (see Supplementary material, section 3). These items were devised by the study authors; no psychometric data are available.

Additional treatment phase measures

Goal-based outcomes (GBOs; Law & Jacob, Reference Law and Jacob2013)

Parents identified up to three therapeutic goals for their child to work towards during the treatment. Parents rated their child’s progress at each treatment session from 0 (no progress towards goal) to 10 (goal achieved). Psychometric data on GBOs are currently limited; however, acceptable internal consistency of GBOs has been shown (Edbrooke-Childs et al., Reference Edbrooke-Childs, O’Herlihy, Wolpert, Pugh and Fonagy2015) and GBOs are widely used in services that offer brief CBT interventions (Ludlow et al., Reference Ludlow, Hurn and Lansdell2020).

Items assessing children’s learning about their fears and their ability to cope in feared situations

Parents completed two items (each on a 5-point scale) after each treatment session to measure their perception of whether their child had learned new information about their fears/worries/obsessions and their ability to cope in feared situations without performing compulsions over the past week (see Supplementary material, section 3). These items were devised by the study authors; no psychometric data are available.

Treatment acceptability measures

Post-treatment questionnaire

All parents who attended at least one treatment session were invited to complete a feedback questionnaire consisting of six closed questions and four open questions assessing the acceptability of the treatment (see Supplementary material, section 3). These items were devised by the study authors; no psychometric data are available.

Session Rating Scale (SRS; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Duncan and Johnson2000)

The SRS was administered at each treatment session to measure the measures therapeutic alliance, and is measured along four 10 cm lines, producing a total score ranging from 0 to 40. The SRS has adequate psychometric properties (Campbell and Hemsley, Reference Campbell and Hemsley2009; Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Miller, Sparks, Claud, Reynolds, Brown and Johnson2003) (see Supplementary material, section 3).

Data analysis

The data analytic plan was pre-registered on the Open Science Framework (see Chessell et al., Reference Chessell, Halldorsson, Walters, Farrington, Harvey and Creswell2022) and deviations from this protocol are outlined.Footnote 1 The primary outcome measure for this study was the CY-BOCS; all other measures were secondary outcome measures (see Chessell et al., Reference Chessell, Halldorsson, Walters, Farrington, Harvey and Creswell2022). Quantitative data were analysed using statistical and visual analyses (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Perdices, Rosenkoetter, Shadish, Vohra, Barlow, Horner, Kazdin, Kratochwill and McDonald2016). Rates of clinical ‘response’ and ‘remission’ were calculated based on the CY-BOCS and ADIS-P (respectively) using guidance from international consensus guidelines (Mataix-Cols et al., Reference Mataix-Cols, de la Cruz, Nordsletten, Lenhard, Isomura and Simpson2016), whereby we defined clinical ‘response’ as ≥35% reduction in CY-BOCS scores for at least one week,2 and clinical ‘remission’ as no longer meeting diagnostic criteria for OCD on the ADIS-P for at least one week. Reliable change was calculated for the CY-BOCS, ChOCI-R-P and FAS-PR from pre-treatment (final baseline scores) to post-treatment, and pre-treatment to 1-month follow-up (Jacobson and Truax, Reference Jacobson and Truax1991). Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated for the CY-BOCS, ChOCI-R-P and FAS-PR from pre-treatment (final baseline scores) to post-treatment, and pre-treatment to 1–month follow-up to ensure comparability with other treatment studies (Lakens, Reference Lakens2013) and were interpreted according to Cohen’s (Reference Cohen1988) conventions. Cohen’s d was calculated using https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html which subtracts the later mean from the baseline mean and divides this by the pooled SD.

Visual analyses were used to assess the extent to which observed gains were likely to be the result of the treatment. Visual analyses used questionnaire data that corresponded to the eight treatment sessions to ensure a consistent approach across participants. Systematic visual analysis involved examination of within- and between-phase changes in: (1) level, (2) trend, (3) data stability, (4) onset of change, (5) overlapping data, and (6) consistency of observations across participants (Kratochwill et al., Reference Kratochwill, Hitchcock, Horner, Levin, Odom, Rindskopf and Shadish2010) and was assisted by https://manolov.shinyapps.io/Overlap/ (Manolov, Reference Manolov2018). Here, the trend line was fitted using the mean absolute scaled error (MASE) method, and stability was assessed using the trend stability envelope (where stability was shown if 80% of the data points fell within 25% of the stability envelope; Lane and Gast, Reference Lane and Gast2014). Individual participant outputs from https://manolov.shinyapps.io/Overlap/ are shown in Supplementary material, section 4. Visual analyses were used to determine whether the intervention showed a ‘clear’, ‘possible’ or ‘little-to-no’ effect on participants’ outcomes, with particular weight given to comparisons of observed and projected intervention values (i.e. where the trend of the baseline data is extrapolated across the intervention phase). A ‘clear’ effect was based on the data pattern in the intervention phase being sufficiently different from what would be expected from the baseline phase data (Horner et al., Reference Horner, Carr, Halle, McGee, Odom and Wolery2005). A ‘possible’ effect was concluded when visual analyses showed improvements in participants’ outcomes; however, these improvements were not superior to the improvements projected from the baseline data. ‘Little-to-no’ effect was concluded when visual analyses showed limited improvements or a deterioration in participants’ outcomes following the introduction of the intervention.

For brevity in the Results section, plots illustrating trend stability, overlapping data, and observed and projected intervention phase values are shown in Supplementary material section 4. Analyses of parents’ knowledge and confidence to help their child to overcome OCD and children’s learning about their fears and their ability to cope in feared situations are reported in the supplementary analyses only (see Supplementary material, section 5). Treatment acceptability data are briefly reported in the Results section, with additional information presented in the Supplementary material (section 5).

Results

Missing data

One participant (P4, who was allocated to a 4-week baseline) did not complete their final baseline questionnaire. We therefore analysed their data as if they were allocated to a 3-week baseline. One family (P1) did not complete the post-treatment ADIS-P and CY-BOCS, and one family (P10) completed their follow-up ADIS-P and CY-BOCS two months after completing treatment (rather than one month). For diagnostic measures, we present both intention-to-treat (ITT) and completer analyses.

Participant descriptives

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Participants were ten children aged 9–12 years old (M=10.9 years, SD=1.1 years, 70% female) and their parent(s). Primary parents (i.e. parents who attended all assessment/treatment sessions and who completed the weekly baseline and treatment measures) were eight mothers and two fathers. They all completed the treatment and received eight treatment sessions. For five families, an additional parent (one mother and four fathers) attended four or more treatment sessions (range=4–8 treatment sessions, mean=6.6 treatment sessions). Eight children were White British, one child was White and Asian, and one child was White and Black African. Nine parents identified as White British, and one parent identified as British Indian. Children’s pre-treatment ADIS-P clinical severity rating (CSR) scores ranged from moderate (i.e. CSR of 4 to 5, n=6) to severe (i.e. CSR of 6 or 7, n=4), and children’s pre-treatment CY-BOCS scores ranged from moderate (i.e. CY-BOCS score of 14–24, n=6) to moderate-severe (i.e. CY-BOCS score of 25–30, n=4; Lewin et al., Reference Lewin, Piacentini, De Nadai, Jones, Peris, Geffken and Storch2014).

Table 1. Participant descriptives

To preserve anonymity, parent and child age are presented as ranges, and parent and child ethnicity are not reported here. For five families, two parents attended four or more treatment sessions. Demographic information was only obtained for the primary parent (i.e. the parent who attended all assessments/treatment sessions and who completed the weekly baseline and treatment measures), 1One parent identified that their child was diagnosed with Tourette’s disorder; however, this was not formally assessed as part of this study; ADIS-P, Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule-Parent Report; CSR, clinical severity rating; CY-BOCS, Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale.

Clinical response and remission

On the primary outcome measure (i.e. the CY-BOCS), 40% (n=4/10, ITT; 44%, n=4/9, completer) of children met criteria for ‘clinical response’ at post-treatment, and 40% (n=4/10, ITT; 40%, n=4/10, completer) at the 1-month follow-up. On the secondary outcome measure (i.e. the ADIS-P), 60% (n=6/10, ITT; 67%, n=6/9, completer) of children met criteria for ‘clinical remission’ at post-treatment, and 50% (n=5/10, ITT; 50%, n=5/10, completer) at the 1-month follow-up assessment. Forty percent (n=4/10, ITT; 40%, n=4/10, completer) of children met criteria for one or more co-morbid diagnoses on the ADIS-P at the 1-month follow-up, specifically social anxiety disorder (n=2), separation anxiety disorder (n=1), specific phobia (n=1), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD, n=1).Footnote 2

Reliable change (Jacobson and Truax, Reference Jacobson and Truax1991)

On the primary outcome measure (i.e. the CY-BOCS), 60% (n=6/10, ITT; 67%, n=6/9 completer) of children showed reliable improvement at post-treatment, and 70% (n=7/10, ITT; 70%, n=7/10, completer) at the 1-month follow-up. On the secondary outcome measure, 50% (n=5/10, ITT; 50%, n=5/10 completer) of children showed reliable improvement on ChOCI-R-P symptom scores at post-treatment and at the 1-month follow-up. Sixty percent (n=6/10, ITT; 60%, n=6/10, completer) of children reliably improved on ChOCI-R-P impairment scores and no longer scored in the clinical range at post-treatment. These six children also scored in the non-clinical range at the 1-month follow-up; however, only five of these children showed reliable change on impairment scores from the baseline phase. Forty percent (n=4/10, ITT; 40%, n=4/10, completer) of families showed reliable improvement in FAS-PR scores at post-treatment and at the 1-month follow-up.

Effect sizes

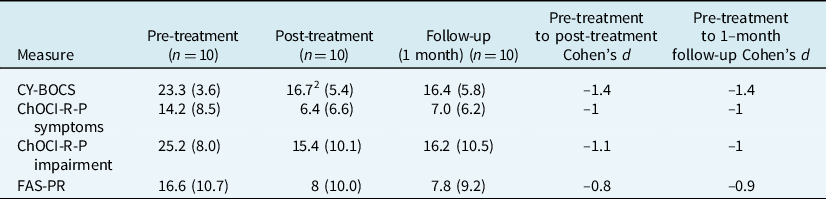

Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for the CY–BOCS, ChOCI-R-P and FAS-PR were calculated using completer data (see Table 2). Large effect sizes were observed for all measures at each time point.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and effect sizes for outcome measures 1

1 Effect sizes were calculated using completer data only. 2 n=9. CY–BOCS, Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; ChOCI-R-P, Children’s Obsessional Compulsive Inventory-Revised-Parent Report; FAS-PR, Family Accommodation Scale-Parent Report.

Visual analyses

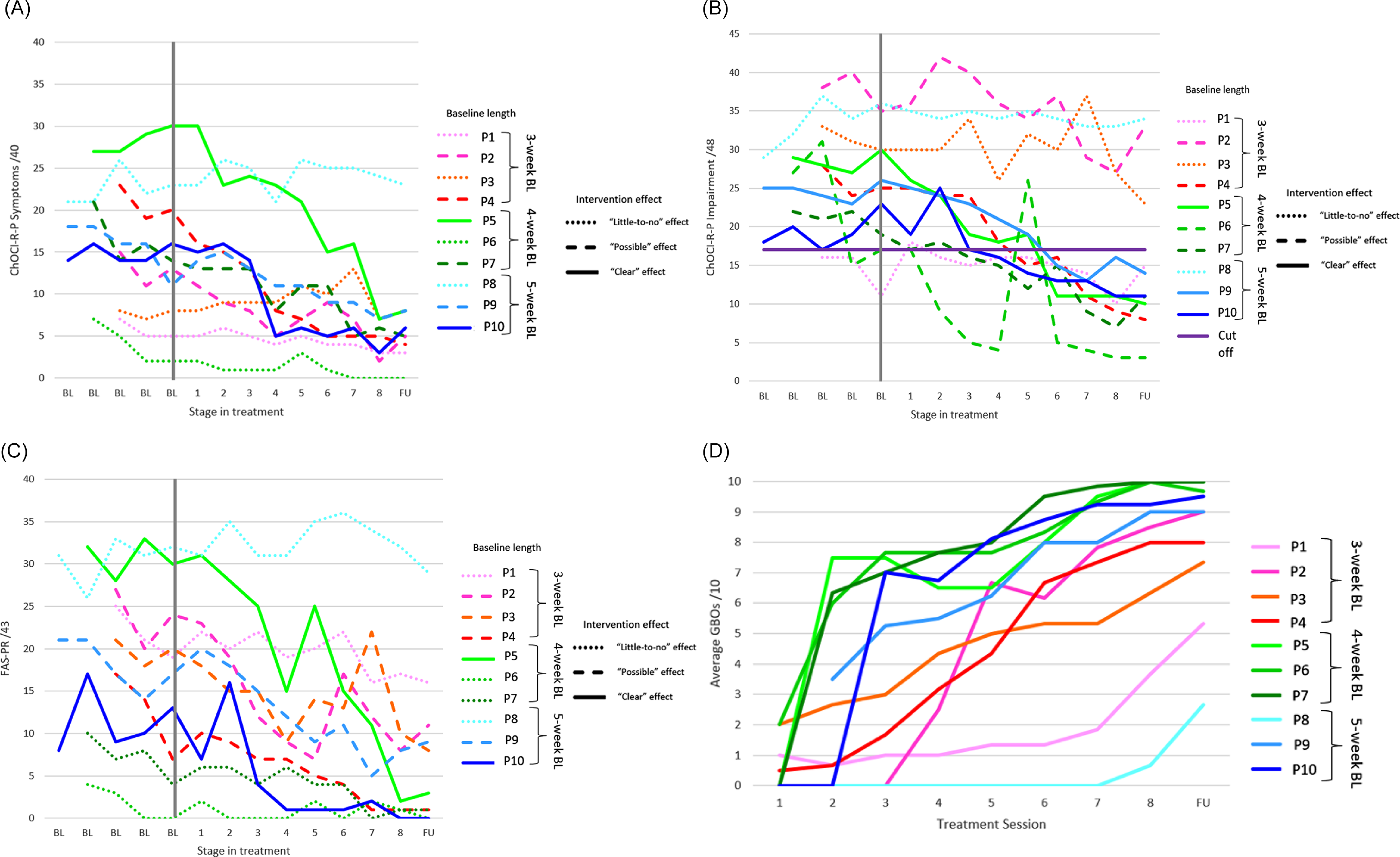

Individual participant data for the ChOCI-R-P symptoms, ChOCI-R-P impairment and FAS-PR are shown in Fig. 3A–C, respectively.

Figure 3. A, individual ChOCI-R-P symptoms; B, individual ChOCI-R-P impairment scores; C, individual FAS-PR scores; D, averaged goal-based outcomes (GBOs) for each participant. ChOCI-R-P, Children’s Obsessional Compulsive Inventory-Revised-Parent Report; FAS-PR, Family Accommodation Scale-Parent Report; BL, baseline; FU, 1-month follow-up. Dotted lines denote ‘little-to-no’ effect of the intervention; dashed lines denote a ‘possible’ effect of the intervention; continuous horizontal lines denote a ‘clear’ effect of the intervention; continuous vertical line denotes final baseline data point; continuous purple horizontal line denotes clinical cut-off for the ChOCI-R-P.

ChOCI-R-P symptoms

Visual analyses revealed a ‘clear’ effect of the intervention in reducing OCD symptoms for two participants (P5, P10), a ‘possible’ effect for four participants (P2, P4, P7, P9) and ‘little-to-no’ effect for four participants (P1, P3, P6, P8). Where there were ‘clear’ effects, participants either had a deteriorating (i.e. an increase in OCD symptoms, P5) or a zero-celerating (i.e. neither improving nor deteriorating) baseline trend (P10) followed by an overall improving treatment trend and reduction in average OCD symptoms across phases. Where there were ‘possible’ effects, all participants had improving baseline trends, which continued to improve (albeit, in most cases, at an overall slower rate) during the treatment phase (P2, P4, P7, P9). Where ‘little-to-no’ effect of the intervention was observed, two participants had improving baseline trends which continued to improve (at an overall slower rate) during the treatment phase, as well as limited reductions in their average OCD symptom scores across phases (P1, P6). One participant had a deteriorating baseline trend but showed a small overall improving treatment trend (P8), and one participant had a zero-celerating trend in both phases (P3). Furthermore, both of these participants experienced an increase in average OCD symptom scores across phases. Overall, the majority of participants experienced an initial reduction in OCD symptoms during the first four treatment sessions.

ChOCI-R-P impairment

Visual analyses showed a ‘clear’ effect of the intervention in reducing impairment scores for three participants (P5, P9, P10), a ‘possible’ effect for four participants (P2, P4, P6, P7) and ‘little-to-no’ effect for three participants (P1, P3, P8). Where there were ‘clear’ effects, participants either had a small improving baseline trend (P5, P9) or a deteriorating baseline trend (P10) followed by clear overall improving treatment trends and a reduction in average impairment scores across phases. Where there were ‘possible’ effects, all participants had overall improving baseline and treatment trends and experienced a reduction in average impairment scores across phases. Where there was ‘little-to-no’ effect, two participants (P1, P3) had overall improving trends during the baseline and treatment phase; however one participant (P1) had an increase in average impairment scores during the treatment phase and one participant (P3) showed limited improvement in average scores across phases. One participant (P8) had a deteriorating baseline trend and a small improving treatment trend but experienced limited change in average impairment scores across phases. The majority of participants experienced an initial reduction in OCD impairment between the second and fourth treatment sessions.

FAS-PR

Visual analyses showed a ‘clear’ effect of the intervention in reducing family accommodation for two participants (P5, P10), a ‘possible’ effect for four participants (P2, P3, P4, P9) and ‘little-to-no’ effect for four participants (P1, P6, P7, P8). Where there were ‘clear’ effects, participants either had a zero-celerating (P5) or a deteriorating baseline trend (P10) followed by an overall improving treatment trend and reduction in average family accommodation symptoms across phases. Where there were ‘possible’ effects, all participants had overall improving baseline and treatment trends and experienced a reduction in average scores across phases (P2, P3, P4, P9). Where there was ‘little-to-no’ effect, three participants had improving baseline trends (P1, P6, P7) that either continued to improve (but at an overall slower rate) during the treatment phase (P1, P7) or showed a zero-celerating treatment trend (P6). One participant (P8) had a deteriorating baseline phase and zero-celerating treatment trend. Three participants showed small average reductions in scores across phases (P1, P6, P7) and one participant showed an increase in average scores (P8). Overall, the majority of parents reported an initial reduction in family accommodation during the first four treatment sessions.

Goal-based outcomes

Participants’ progress towards each of their treatment goals was averaged (see Fig. 3D). All participants made progress towards their goals during the treatment; however, two participants (P1, P8) made less progress than the others. Interestingly, participants with a 4-week baseline appeared to make the fastest initial gains towards their treatment goals.

Treatment acceptability

Post-treatment questionnaire

All parents who completed the post-treatment questionnaire (n=11 out of 15, 73% response rate) ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that they were satisfied with the treatment, the length of the treatment, and would recommend the treatment. Ten parents ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that they were satisfied with the number of treatment sessions, the outcomes of treatment, and felt equipped to help their child. One parent neither agreed nor disagreed with these statements (see Supplementary material, section 5).

SRS

Parents’ average total SRS scores across all treatment sessions (M=38.7, SD=2.8) and each individual treatment session were above the cut-off of 36, indicating that the treatment was broadly acceptable to parents (see Supplementary material, section 5).

Discussion

We used a multiple baseline approach to evaluate the initial efficacy and acceptability of an adapted brief therapist-guided, parent-led CBT intervention for pre-adolescent children with OCD. Promising outcomes were shown, with 70% (ITT; 78% completer) of children classed as ‘responders’ (on the CY-BOCS) and/or ‘remitters’ (on the ADIS-P) at post-treatment, and 60% (ITT; 60% completer) at the 1-month follow-up. Moreover, the majority of children showed reliable improvements on the CY-BOCS, ChOCI-R-P symptom scores, and ChOCI–R-P impairment scores at post-treatment and at follow-up, and just under half of parents reported reliable improvements in family accommodation at these time points. Reductions in the number and severity of co–morbid diagnoses were also observed across the sample at the 1-month follow-up. Parents reported gradual improvements in their child’s learning about their fears/their ability to cope throughout the treatment, as well as their own knowledge and confidence to help their child to overcome OCD, and the treatment was found to be acceptable to parents.

Notably, treatment outcomes varied depending on the measure and method of analysis. For example, on the primary outcome measure (i.e. the CY-BOCS), only 40% (ITT; 44% completer) of children met criteria for ‘response’ at post-treatment and at the 1-month follow-up (40% ITT; 40% completer), whereas 60% (ITT; 67% completer) of children showed reliable change on this measure from pre- to post-treatment and 70% (ITT; 70% completer) from pre-treatment to the 1-month follow-up. Our definition of treatment ‘response’ on the CY-BOCS was informed by international consensus guidelines (i.e. ≥35% reduction; Mataix-Cols et al., Reference Mataix-Cols, de la Cruz, Nordsletten, Lenhard, Isomura and Simpson2016) which are more conservative than other guidelines (i.e. >25% reduction; Storch et al., Reference Storch, Lewin, De Nadai and Murphy2010). Furthermore, discrepancies between ‘response’ rates on the CY-BOCS at post-treatment (i.e. 40% ITT; 44% completer) and at follow-up (40% ITT; 40% completer) and ‘remission’ rates on the ADIS-P at post-treatment (60% ITT; 67% completer) and follow-up (50% ITT; 50% completer) (which were notably higher than CY-BOCS ‘response’ rates) may be the result of the CY-BOCS being primarily conducted with the child (with the parent present to add additional information where necessary) whereas the ADIS-P was conducted with parents only. Such parent–child discrepancies have been noted in other OCD treatment trials (e.g. Storch et al., Reference Storch, Murphy, Adkins, Lewin, Geffken, Johns and Goodman2006). Although international consensus guidelines suggest prioritising parent-report for pre-adolescent children with anxiety disorders (Krause et al., Reference Krause, Chung, Adewuya, Albano, Babins-Wagner, Birkinshaw, Brann, Creswell, Delaney and Falissard2021), future evaluations of this treatment may benefit from combining the information obtained from parent and child diagnostic interviews. Encouragingly, reliable change indices for parent-reported ChOCI-R-P symptom and impairment scores at post-treatment and at 1-month follow-up closely reflected ‘remission’ rates on the ADIS-P, suggesting that parents were reporting consistently across measures.

When examining the visual analyses of the ChOCI-R-P symptom and impairment scales, although the majority of participants showed promising outcomes, four participants showed limited improvements on at least one of these scales. For two of these participants this may reflect floor effects, where parents reported low symptom (P1, P6) or impairment (P1) scores during the baseline period. However, some parents (P1, P8) found it challenging to engage their child in their step-by-step ERP plan, potentially due to child fear (Mancebo et al., Reference Mancebo, Eisen, Sibrava, Dyck and Rasmussen2011). Thus, the lack of improvement for these participants is unsurprising given that exposure to fears/feared situations is key for treatment change (Peris et al., Reference Peris, Compton, Kendall, Birmaher, Sherrill, March, Gosch, Ginsburg, Rynn and McCracken2015; Whiteside et al., Reference Whiteside, Sim, Morrow, Farah, Hilliker, Murad and Wang2020). Future evaluations of this treatment should therefore consider additional ways to support parents to engage their children in exposure-based approaches, for example, by providing parents with greater psychoeducation on the use of rewards for motivating children (Bouchard et al., Reference Bouchard, Mendlowitz, Coles and Franklin2004). Finally, despite the remaining participant (P3) experiencing over 40% reduction in their CY-BOCS scores at post-treatment, limited improvements were observed on their parent-reported ChOCI-R-P symptom and impairment scores, which may reflect discrepancies in parent and child report.

The outcomes of this research are encouraging when compared with other OCD treatment trials for children. In line with meta-analytic research (McGuire et al., Reference McGuire, Piacentini, Lewin, Brennan, Murphy and Storch2015), we observed large effects on all outcome measures from pre- to post-treatment. Furthermore, these effect sizes were consistent with a brief individual CBT intervention for children and adolescents with OCD (consisting of 7 hours of therapist support; Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Williams, Perrin, Atkinson, Gallop, Waite and Salkovskis2011) and a parent-led CBT intervention for young children with OCD (consisting of 12 hours of therapist support; Rosa-Alcázar et al., Reference Rosa-Alcázar, Iniesta-Sepúlveda, Storch, Rosa-Alcázar, Parada-Navas and Olivares Rodríguez2017; Rosa-Alcázar et al., Reference Rosa-Alcázar, Rosa-Alcázar, Olivares-Olivares, Parada-Navas, Rosa-Alcázar and Sánchez-Meca2019). However, notably, the pre–post treatment CY-BOCS effect sizes seen in Rosa-Alcázar et al. (Reference Rosa-Alcázar, Iniesta-Sepúlveda, Storch, Rosa-Alcázar, Parada-Navas and Olivares Rodríguez2017, Reference Rosa-Alcázar, Rosa-Alcázar, Olivares-Olivares, Parada-Navas, Rosa-Alcázar and Sánchez-Meca2019) (d=–3.4 in both studies) were considerably larger than the current study (and the majority of other treatment trials in this field) due to particularly small standard deviations and lower post-treatment mean CY-BOCS scores. Comparison of ‘response’ and ‘remission’ rates with other OCD trials is challenging, given that previous studies have used inconsistent criteria (Mataix-Cols et al., Reference Mataix-Cols, de la Cruz, Nordsletten, Lenhard, Isomura and Simpson2016).

Strengths of this study include the evaluation of a brief treatment for pre-adolescent children with OCD that was delivered by a non-specialist therapist. In line with Bower and Gilbody’s (Reference Bower and Gilbody2005) criteria for first-line interventions, this treatment has shown promising outcomes compared with other CBT treatments for children with OCD, requires considerably less therapist input than traditional CBT approaches, and shows promising acceptability to parents. Moreover, we included children with co-morbid diagnoses (with the exception of autism/learning disabilities) and children who had previously received psychological support, increasing the generalisability of our findings to routine clinical practice. Given the tendency for parent involvement in treatment to predominantly involve mothers (e.g. Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Healy-Farrell and March2004), we were pleased that six fathers participated in at least one treatment session (four attended all eight sessions), particularly given that both maternal and paternal accommodation of OCD symptoms have been associated with children’s treatment outcomes (Monzani et al., Reference Monzani, Vidal-Ribas, Turner, Krebs, Stokes, Heyman, Mataix-Cols and Stringaris2020). This level of father engagement may reflect the flexible treatment delivery (i.e. remote appointments, evening appointments) (Thurston and Phares, Reference Thurston and Phares2008). The use of a multiple baseline approach enabled us to examine the effect of the intervention whilst controlling for factors that may impact internal validity (e.g. time, external events that coincide with the introduction of the treatment, etc.; Kratochwill et al., Reference Kratochwill, Hitchcock, Horner, Levin, Odom, Rindskopf and Shadish2010). Our results indicated that treatment gains were not influenced by baseline length (with the potential exception of treatment goals), strengthening the conclusions that can be made regarding treatment efficacy (Kazdin, Reference Kazdin2019; Watson and Workman, Reference Watson and Workman1981).

Despite these strengths, there are important limitations to consider. First, although the sample size (n=10) is appropriate for this study design (i.e. Kratochwill et al., Reference Kratochwill, Hitchcock, Horner, Levin, Odom, Rindskopf and Shadish2010), the generalisability of the conclusions are limited and it will be crucial to examine this intervention on a larger scale (i.e. using a sufficiently powered randomised controlled trial) to draw firm conclusions regarding treatment efficacy. Second, a number of participants had improving baseline trends, meaning that we could not infer with confidence whether there was a ‘clear’ effect of the intervention, as there was a considerable overlap between the observed and projected treatment data. Given that OCD is often chronic in nature (Micali et al., Reference Micali, Heyman, Perez, Hilton, Nakatani, Turner and Mataix-Cols2010), we would not typically expect participants’ improving baseline trends to continue in a linear fashion. Furthermore, we calculated participants’ treatment trends based on all of their session-by-session data, despite not anticipating observing treatment effects during the first few treatments sessions (when sessions were mainly psychoeducational). Thus, our approach to classifying treatment effects based on visual analyses was conservative. Third, due to the preliminary nature of this research, we were unable to use blind assessors to conduct and score diagnostic assessments, which may have resulted in over-estimated treatment effects (Savović et al., Reference Savović, Turner, Mawdsley, Jones, Beynon, Higgins and Sterne2018). Whilst we also used parent-reported questionnaires to assess treatment efficacy, the lack of assessor blinding means that the results of this study need to be interpreted with caution. Moreover, the items assessing parents’ knowledge and confidence to help their child to overcome OCD, and parents’ perception of whether their child had learned new information about their fears and their ability to cope in feared situations (see Measures section) were specifically designed for this study and have not been psychometrically tested – thus, the results of these measures should also be interpreted with caution. Fourth, we used a between-groups measure of Cohen’s d to calculate effect sizes that were comparable to other treatment studies – however, this effect size does not consider the relationship between pre- and post-/follow-up treatment data and may therefore have resulted in inaccurate effect size calculations. Fifth, we only conducted a 1-month follow-up of participants, limiting our understanding of the longer-term impacts of this intervention. Sixth, our sample predominantly consisted of White British children and parents. Although this reflects families who typically access CAMHS services (Messent and Murrell, Reference Messent and Murrell2003), the lack of ethnic diversity restricts our understanding of the efficacy and acceptability of this treatment for families from more diverse backgrounds. Seventh, although our sample included children with moderate to severe pre-treatment OCD symptoms, no children met criteria for very severe OCD – thus, the applicability of this approach to children with very severe OCD remains unknown. Eighth, we did not assess other variables that may be related to children’s treatment outcomes (e.g. parental mental health difficulties) which may be important to assess in future evaluations of this treatment. Finally, despite the brief nature of this treatment, all families received eight (rather than six) treatment sessions, equating to 6 hours of therapist support. Whilst this is still considerably less therapist support than existing treatments (e.g. Rosa-Alcázar et al., Reference Rosa-Alcázar, Iniesta-Sepúlveda, Storch, Rosa-Alcázar, Parada-Navas and Olivares Rodríguez2017; Rosa-Alcázar et al., Reference Rosa-Alcázar, Rosa-Alcázar, Olivares-Olivares, Parada-Navas, Rosa-Alcázar and Sánchez-Meca2019), it will be important to consider ways to further decrease the amount of therapist support needed, to further increase access to treatment for affected families. Recent research has shown promising outcomes following a brief online therapist-supported, parent-led CBT intervention for pre-adolescent children with anxiety problems, with only 2.5 hours of therapist support (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Chessell, Percy and Creswell2022a). Thus, future research would benefit from considering whether a brief online therapist-guided, parent-led CBT intervention would be a suitable way to further increase access to CBT for pre-adolescent children with OCD.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated promising outcomes for pre-adolescent children with OCD following a brief therapist-guided, parent-led CBT intervention that was delivered by a non-specialist therapist. More rigorous evaluation (i.e. a randomised controlled trial) of this intervention is now warranted and should recruit a demographically diverse sample of children and parents and use independent blind assessors to increase confidence in the intervention effects. However, subject to the findings of further evaluations, our findings suggest that this brief treatment, developed to be delivered by non-specialist therapists, may be a good candidate as a first-line treatment to ultimately substantially increase access to evidence-based treatments for pre-adolescent children with OCD.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465823000450

Data availability statement

The data are not available due to ethical restrictions whereby information could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the charities, OCD-UK and No Panic, who provided feedback on our treatment materials prior to the treatment being delivered to families, and the families who participated in the treatment.

Author contributions

Chloe Chessell: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Resources (lead), Validation (lead), Visualization (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Brynjar Halldorsson: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Funding acquisition (lead), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Supervision (lead), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Sasha Walters: Conceptualization (supporting), Data curation (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (equal), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Alice Farrington: Conceptualization (supporting), Data curation (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Funding acquisition (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Kate Harvey: Conceptualization (supporting), Data curation (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Cathy Creswell: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Funding acquisition (lead), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Resources (equal), Software (equal), Supervision (lead), Validation (equal), Visualization (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number ES/P00072X/1) and from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration Oxford and Thames Valley at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests

C.Cr. receives royalties for the sale of the original treatment book ‘Helping Your Child with Fears and Worries’, but does not receive royalties for any of the treatment materials used in this study.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was obtained from West Midlands–South Birmingham Research Ethics Committee (REC reference: 21/WM/0077) and the University of Reading Research Ethics Committee (UREC: 21/27). Authors abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct set out by the BABCP and BPS, and participants provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.