The emergence and development of the Red Guard papers is a great innovation in the history of the proletarian press and a great victory for Chairman Mao's news line. In the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, the Red Guard newspapers have made tremendous achievements and have earned eternal merit. The Red Guard papers deserve our loud praise.

“In praise of the Red Guard newspapers,” Chen Chen 陈晨Footnote 1Red Guard newspapers, or, more precisely, the publications of revolutionary mass organizations, served as important source materials for the first generation of research on the Cultural Revolution.Footnote 2 Valued for their unbridled accounts of inner-Party struggles and juicy details of factional conflicts, Red Guard publications offered unprecedented insights into high-level national and provincial politics and allowed observers to reconstruct in detail the political and social dynamics of the Maoist People's Republic. Collecting the massive amount of material filtering out of mainland China and making it widely available required a concerted effort by the international research community.Footnote 3 However, with the opening of provincial and local archives in the 1990s, increasing access to participants for oral history projects and the rise of “garbology,” Red Guard newspapers were largely eclipsed as primary sources in a new wave of Cultural Revolution research.Footnote 4 In light of these new materials, the Red Guard papers, with their shrill language, repetitive content and narrow focus, lost much of their historiographical appeal and were relegated to the sidelines of historical research. Yet Red Guard publications have only rarely been considered an object of research in their own right. Few studies have systematically probed the inner dynamic of these publications and their status within the public sphere.Footnote 5 Regardless of their (in)significance as informational sources, Red Guard papers are a vitally important chapter in the history of the modern Chinese public sphere.

Official historiography from the People's Republic of China (PRC) deplores the Cultural Revolution as an aberration, a period of mayhem and destruction across all sectors of Chinese society, including the country's press. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, the number of newspapers in circulation dropped precipitously, from 343 in 1965 to 49 in 1966 and just 43 in 1967 – an all-time low not just for the PRC but for 20th-century China as a whole.Footnote 6 Many mainstream histories of journalism published in the PRC go a step further, matter-of-factly equating the quantitative nosedive with a qualitative decline and a sharp drop in the press's ability to perform its proper journalistic functions.Footnote 7 This view has been accepted uncritically by at least some foreign accounts.Footnote 8 Other numbers, however, tell an entirely different story. At the very moment when hundreds of newspapers and journals across China ceased publication, the number of publications produced by mass organizations skyrocketed. Reliable figures are hard to come by, but the National Library in Beijing holds over 2,600 different titles published between 1966 and 1968. Estimates of the total number of publications reach up to 10,000.Footnote 9 These figures, then, represent the highest number of publications in circulation at any time in 20th-century China.Footnote 10 Yet just as declining numbers are not a proxy for a vanishing public sphere, the explosion of Red Guard publications itself does not represent an indicator for diversity and vibrancy. These numbers, however, reveal dramatic shifts in the structure of the public sphere. How to reconcile these numbers and, accordingly, how to interpret the role of the Red Guard press are highly pertinent issues in the history of the modern Chinese public sphere.

The applicability of the Habermasian notion of the public sphere to the Chinese context has a contentious history.Footnote 11 The People's Republic, with its highly regimented propaganda apparatus and predominance of “Party papers” (dangbao 党报), diverges sharply from the idealized intermediate space of autonomous reasoning that is based on Habermas's analysis of 18th- and 19th-century Europe.Footnote 12 Daniel Lynch describes even the reform era media as but a “praetorian public sphere,” characterized by “the cacophonous and unstructured circulation of communication messages” in an adapting authoritarian context.Footnote 13 Yet the Chinese public, as an increasing amount of research demonstrates, has never been a monolithic entity. Once this singular public is disaggregated into its many constituent units – local and regional press networks, sub-spheres of public communication, niche publics, counter-publics and more – a heterogeneous terrain emerges that allows for more nuanced accounts of seemingly paradoxical phenomena such as the Red Guard press. How do we characterize the nature of these publications, as well as their status and function within the larger information ecosystem of the People's Republic? Was the Cultural Revolution an information “desert” or an “information revolution”?Footnote 14 When the vast majority of newspapers and journals were shut down in the spring and summer of 1966 and central and local propaganda departments were rendered dysfunctional by infighting and power seizures, Red Guard publications emerged as crucial sites of public discourse. The vast body of Red Guard newspapers constitutes a test case to re-examine the functioning of the public in a decidedly “uncivil” polity.

This article situates Red Guard newspapers within their larger historical context, examining their perceived and actual roles in Cultural Revolutionary political culture. A fully fledged account of the Red Guard press's history is impossible in the space of an essay and must await further research. On the following pages, however, I will reflect on the vision of the public sphere formulated by at least some of these publications. In particular, I will address the question of legitimacy: how did the Red Guard press justify its existence and its function within the emerging political and cultural landscape of a radical mass movement? How did these publications position themselves vis-à-vis the leadership in Beijing, the revolutionary mass organizations, and their peers and rivals? And how did they define their relationship with the existing press (dabao 大报)? To answer these questions, I will zoom in on a particular group of Red Guard papers, namely those published by radical groups within the PRC's press and publication system. Intimately familiar with the functioning of the Chinese press since 1949, these papers were uniquely positioned to critique the pre-Cultural Revolution press and, more importantly, to ponder the possible futures of a new, revolutionary Chinese press. At a metadiscursive level, thus, these papers deliberated on their own nature, eventually sketching the contours of an entirely new form of a public sphere – a vision fundamentally different from any previous Chinese public. Promethean and praetorian at the same time, they merged radical anti-establishmentarian and grassroots elements with expressly “uncivil” practices. More empirical work is needed to evaluate how these normative positions translated into the journalistic practices of the Red Guard press. Yet the visions articulated in these papers throw into sharp relief the ambiguous potential of the public for both consensus and conflict, liberation and repression, which characterizes the press in 20th-century China as a whole.

Origins, Legitimacy, Trajectory

There is some disagreement as to what qualifies as the first Red Guard newspaper. Both Hongweibing bao 红卫兵报 (Red Guard News) and Hongweibing 红卫兵 (Red Guard) lay claim to the title “first,” having published their respective first issues on 1 September 1966.Footnote 15 The actual origin of the Red Guard papers, however, must be sought in an altogether different medium: big-character posters (dazibao 大字报). The starting shot for the Red Guard press was arguably Mao's 5 August “Bombard the headquarters: my big-character poster” (Paoda silingbu: wo de yi zhang dazibao 炮打司令部:我的一章大字报).Footnote 16 Big-character posters had been deployed to great effect in previous political campaigns, but they rose to prominence at the onset of the Cultural Revolution with Nie Yuanzi's 聂元梓 inflammatory big-character poster attacking the Peking University leadership on 25 May, which was broadcast publicly on radio a few days later. In his own poster, Mao endorsed not just Nie's attack but also the medium she had chosen. His praise indicated that the border between official and unofficial written sources was becoming porous: both his own and Nie Yuanzi's opinions travelled from big-character posters to the news media, showing the permeability of the border separating the two and thus elevating the posters’ relevance. Big-character posters received a further legitimacy boost a few days later when the Central Committee's famous “August 8” decision called on the revolutionary masses to “make the fullest use of big-character posters and great debates to argue matters out.”Footnote 17 The signature document of the 11th Plenum, which opened the floodgates of the Cultural Revolution, thus endorsed the circulation of grassroots opinion, a momentous shift in the structure of the public sphere. The Red Guard papers that were soon springing up everywhere self-consciously referred to the rhetoric of grassroots debate and big-character posters to enhance their own legitimacy.

From early September 1966, there was an explosion of Red Guard publications across the country. Yet these publications were not uniform in style or form, and the organizations publishing these papers were as heterogeneous as the publications themselves. The publications ranged from crudely mimeographed tabloids that lasted for just one or two issues to papers printed with professional metal type in broadsheet format which ran for years and very occasionally made the leap from “small paper” to mass medium. The Red Guard press is often referred to as xiaobao 小报 (tabloid), a term that in both English and Chinese carries negative connotations. Contemporary official documents tend to use the more precise though bulky moniker geming qunzhong zuzhi baokan 革命群众组织报刊 (newspapers and periodicals of revolutionary mass organizations). The notion of “Red Guard papers” is, in short, vague: it denotes a large and heterogeneous group of publications and it is characterized by fuzzy borders with the official press.

The rise of the Red Guard press was a radical break with the institutional conventions of journalism established after the founding of the People's Republic.Footnote 18 Ever since 1949, the socialist Chinese press had been closely intertwined with the political-ideological regulatory structures embodied in the propaganda system. Party papers (dangbao) occupied the apex of this system at the national and provincial levels, and the integration of the press – Party papers and others alike – into the propaganda system had been ensured through Party committees within these work units. The assault on the Central Propaganda Department, declared a “demon's den” (yanwang dian 阎王殿) by Mao, had rendered this central node of the propaganda system dysfunctional by late 1966. Following Lu Dingyi's 陆定一 overthrow, the Propaganda Department ceased to function and was not rebuilt until 1977. Without support of the centre, local propaganda bureaus also came under assault and the surviving newspapers were left to figure out by themselves how to engage in journalism amid a disruptive political campaign. The Red Guard papers faced an analogous situation. There was no precedent, no institutional chain of command and no obvious model to follow. They had to reinvent journalism. Mao had called for “smashing the demon's den” and “liberating the small devils” (jiefang xiao gui 解放小鬼).Footnote 19 Having achieved their freedom, the papers had to figure out what to do next.

Red Guard newspapers did what they could. In search of legitimacy, they turned to two sources: Chairman Mao and the big papers. From their onset, Red Guard publications generally tried to emulate the big papers and especially the esteemed Renmin ribao 人民日报. This presented a conundrum, as the big papers were the targets of attack and an “old” mode to be overcome. In many respects, however, they were the only model available. Red Guard newspapers adopted standard journalistic practices, publishing founding notices (fakanci 发刊词), editorials (shelun 社论) and commentator articles (ben bao pinglunyuan 本报评论员). The Red Guard press frequently reprinted articles from People's Daily, Liberation Army Daily (Jiefangjun bao 解放军报) and Red Flag (Hongqi 红旗), which was a practice common for provincial-level papers. They also peppered their articles with quotations from Chairman Mao, copying the practice, established by People's Daily at the start of the Cultural Revolution, of setting these quotations in bold print. Most notably, Red Guard papers imitated the visual appearance and layout of the big papers. They ran quotations from Chairman Mao on the top of the frontpage and invariably chose Mao's calligraphy for their masthead. All of these practices were designed to bolster their legitimacy and limit their vulnerability in a volatile political environment.

The fortunes of the Red Guard press waxed and waned over the ensuing months, closely tracking the shifts in the Cultural Revolution's political direction. They thrived with the Red Guard movement in the autumn of 1966 and received a further boost in January 1967 as the Cultural Revolution entered its most radical phase. During another radical phase, in May 1967, the Central Committee issued the first ever circular that officially acknowledged the Red Guard press. The promulgation of the “Opinions on improving the press and propaganda of revolutionary mass organizations” was an attempt to establish rules for the rapidly proliferating Red Guard press.Footnote 20 The “Opinions” endorsed the existence and function of the Red Guard press: “In the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, the papers and leaflets compiled and printed by revolutionary mass organizations play an important role on the propaganda front.”Footnote 21 The document also encouraged these mass organizations to “consult important editorials and commentaries of People's Daily, Red Flag and Liberation Army Daily for their own propaganda.”Footnote 22 The effort to more closely integrate the mainstream press with the Red Guard papers and to establish a rule-based system demonstrates an attempt to envision a new structure for the public sphere, a structure with a permanent place for the Red Guard press.

At other times, attempts to rein in the revolutionary mass organizations, such as in February, June and September 1967, also hurt these organizations’ propaganda organs. A document issued by the Beijing Municipal Revolutionary Committee on 30 June, for instance, called for out-of-town Red Guards to leave the city and ordered local mass organizations to confine their activities to their home units, a measure that affected the burgeoning Red Guard press in the capital.Footnote 23 The Beijing authorities reiterated these demands in the wake of the Wuhan Incident. A decree issued on 8 September bluntly declared, “Out-of-town people are forbidden to set up liaison stations in universities, schools, organs or work units in Beijing, and they are not allowed to publish newspapers in Beijing.”Footnote 24 After September 1967, the vast majority of Red Guard papers across the nation were forced to close down. By early 1968, only the most prestigious papers remained – i.e. those published by large umbrella organizations and thus with the strongest claims to legitimacy.

Journalistic Metadiscourses

The proliferation of Red Guard publications at the very moment when the regulatory structures of the propaganda system were disintegrating did not result in the growth of a public sphere in the Habermasian sense. Neither the numerical explosion of press outlets nor the shrill denunciations dominating their pages make a case for an intermediate sphere of public reasoning. But how, then, did the Red Guard papers envision their own role and the future of journalistic practice in China? While it is impossible to generalize about such a large and heterogenous body of material, some answers may be gleaned from the more self-consciously reflexive among the Red Guard press. I therefore turn to a special segment within the vast landscape of Red Guard newspapers: publications of mass organizations within the news media themselves. Just like in other work units, “revolutionary rebels” seized power in newspaper offices across the nation and soon set out to publish their own papers. And, just as elsewhere, these papers provided a platform to denounce the old leadership, detailing its mistakes and misdeeds. They hence offer important insights into the functioning of the press before 1966. At the same time, these papers contain deliberations about the efforts to move beyond the mistakes of the past and create a genuinely new journalism. In the course of these debates, these papers inevitably reflect on themselves and about the Red Guard press as an institution.

Such metadiscursive publications constitute a small but significant subset of the Red Guard press. A rebel organization of Xinhua News Agency employees, for instance, published the short-lived Xinhua zhanbao 新华战报 (Xinhua Battle Bulletin, four issues, 12 May–15 September 1967).Footnote 25 Another group, also from Xinhua News Agency, allied with the journalism branch of a larger coalition of rebels to issue Xinwen zhanxian 新闻战线 (News Front).Footnote 26 Journalists at the prestigious Guangming ribao 光明日报 (Guangming Daily) founded Guangming zhanbao 光明战报 (Guangming Battle Bulletin).Footnote 27 Likewise, rebels at local newspapers in Guangzhou, Guangxi, Fuzhou and Hunan all produced their own papers.Footnote 28 Perhaps the most interesting of these self-reflexive publications is Xinwen zhanbao 新闻战报 (News Battle Bulletin).Footnote 29 Founded by a coalition of rebel groups calling itself the “Capital news criticism liaison station,” Xinwen zhanbao published a total of 19 issues, making it one of the longest lasting publications in the news sector. It boasted extensive ties with other papers and with the leading journalism research institutions, lending it considerable theoretical firepower.Footnote 30 Through its umbrella organization, Hongdaihui 红代会 (Red Guard Congress), Xinwen zhanbao maintained close relations with the Cultural Revolution Small Group, the radical hardcore clique surrounding Jiang Qing 江青 and Zhang Chunqiao 张春桥.Footnote 31 In the six months of its existence, Xinwen zhanbao produced a significant amount of theoretical reflections about the Chinese press. Writing from the apex of the Chinese news sector, the paper's authors offered its readers extensive insights into past and current developments of journalism in socialist China, making the paper an essential source for the Cultural Revolution in the news sector.

The inaugural issue of Xinwen zhanbao, dated 28 April 1967, offers a good overview of the main issues occupying the paper, its general tone and its discursive structure. The front page, apart from an oversized portrait of the Chairman, consists of a collection of Mao quotations related to the press. Page two contains an editorial, a report on the Liaison Station's founding, and brief news items from the news sector itself. On page three, a lengthy article denounces Liu Shaoqi's 刘少奇 policies on news and propaganda. Page four, finally, must be read as an inversion of page one: under the title “Liu Shaoqi's black words in journalistic circles,” readers find extensive quotations on the press from Liu. With Mao's instructions on the one hand, and Liu's utterances on the other, the discursive field for the assessment of the Chinese press and the theoretical tenets guiding this field have been staked out. The Cultural Revolution in the news sector, as elsewhere, is presented as the culmination of an extended struggle between two lines represented by Mao and Liu.

The logic of two-line struggle is formulated in one of the quotations gracing Xinwen zhanbao's front page, which in fact is taken from the 8 August 1966 Central Committee decision: “To overthrow a political power, it is always necessary, first of all, to create public opinion, to do work in the ideological sphere. This is true for the revolutionary class as well as for the counter-revolutionary class. This thesis of comrade Mao Zedong's has been proved entirely correct in practice.”Footnote 32 The press, in other words, is a site of acute class struggle and both sides use it for their own political purposes. Xinwen zhanbao hence sets out to dig up evidence of Liu Shaoqi's attempts to manipulate the press in order to undermine Chairman Mao's revolutionary line. An article in issue eight, for example, denounces the “three black flags” (san mian heiqi 三面黑旗) of Liu Shaoqi's press theory: (1) the allegedly bourgeois concepts of “truthfulness” (zhenshi 真实), “impartiality” (gongzheng 公正) and “objectivity” (keguan 客观); (2) the idea of “press freedom” (xinwen ziyou 新闻自由); and (3) the notion of “entertainment” (quweixing 趣味性).Footnote 33 In a society where class struggle still exists, so the authors write, there can be no such notions as impartiality and objectivity; any compromise with bourgeois ideas advantages the class enemy and works against the revolutionary proletariat. “The proletarian press is a tool of the dictatorship of the proletariat,” the article declares. “Therefore, it must resolutely stand on the proletariat's side and make propagating and defending the invincible Mao Zedong Thought its most basic task.”Footnote 34 The Chinese press under Liu Shaoqi's command had erred on this account. The article offers ample “evidence” of perceived mistakes that often went back to the 1950s, and the authors do not hesitate to twist Liu's words by quoting them out of context.Footnote 35 They are unapologetic about these partisan distortions – they are not bound to impartiality and objectivity, and the article itself is a demonstration of the new journalistic practices proposed by Xinwen zhanbao.

Xinwen zhanbao and other papers of the metadiscursive variety thus embarked on a dual mission: to criticize pre-Cultural Revolutionary journalistic practices and to propose new modes of journalism. While both of these tasks were intertwined, the papers tended to dwell on the criticism of the “Liu line,” which apparently was the easier part of their mission. The demand for partiality, in theory as well as practice, was not in fact a new one. Partiinost (dangxing 党性), or party-mindedness, had been a crucial requirement of the Communist press in both the Soviet Union and China before and after 1949. Papers such as People's Daily can hardly be called objective or impartial, nor were they ever supposed to be. What the Red Guard press accuses Liu Shaoqi and the PRC's propaganda system of, then, is having not lived up to the demands of a proper Communist press. They denounce the Propaganda Department and the papers under its control for having followed the (essentially correct) guidelines of a true Communist press in a half-hearted manner. What was wrong with the Chinese press before 1966, in other words, was not so much its premises, but rather its failure to reflect these premises in actual journalistic practice. Far from regarding the public sphere as an autonomous space, then, the journalism promoted by Xinwen zhanbao makes a case for a battlefield, a site of acute struggle between antagonistic parties. Its position is decidedly praetorian – in a setting without effective hierarchical controls and valid rules of engagement, extreme partisanship prevails.

There was, however, one problem the paper and its peers had to grapple with: how to ensure the proper direction of the press in such a praetorian public sphere? The Party organization and its surrogates in the editorial rooms of the nation's press had proven themselves unreliable guardians of the partisan position in the two-line struggle. But if the Party and its official press could not be entrusted with the stewardship of public communication, who else could guarantee that the nation's press would uphold the correct line? Who would be the stewards and the guardians of the radical public of the future? Deliberations on this most crucial problem, on the central conundrum of the Cultural Revolutionary public sphere, would lead the metadiscursive papers to some surprising conclusions.

The Power of the Masses

Chairman Mao has taught us: “The people, and only the people, are the moving force creating world history.” The mass line is the fundamental line of a proletarian political party. How they treat the masses is the benchmark for revolution, non-revolution and counterrevolution, and it has always been the focus for the proletariat's revolutionary line and the bourgeoisie's reactionary line. In the same manner, there exists a fierce two-line struggle on the question of how to run newspapers.Footnote 36

An article signed Lu Qun 路群 (an apparent allusion to qunzhong luxian 群众路线, or mass line, a crucial Maoist concept) in the 30 July issue of Xinwen zhanbao addresses the issue of two-line struggle but shifts the emphasis in a new direction: the role of the masses.Footnote 37 The problem of a mass line in journalism – how to write for the masses and also give them a voice – had haunted Chinese socialist journalism since the 1940s, a tension that troubled other industries as well and was captured in the formula “both red and expert.”Footnote 38 Articles in Xinwen zhanbao and other metadiscursive papers routinely accuse Liu Shaoqi of ignoring or circumventing the demands of the mass line. For a bottom-up revolutionary movement, the question of mass involvement was naturally of crucial importance and the Red Guard papers seemed to propose a solution to the red/expert conundrum. They themselves represented a genuinely popular form of journalism. Could the emerging Red Guard press effectively do away with the pretentions of a politically suspect, exclusive journalistic professionalism?

The Lu Qun article promises a frontal attack on professionalism in the press. Entitled “Open ferocious fire on Liu Shaoqi's ‘professional’ journalistic line” (Xiang Liu Shaoqi de “zhuanjia” ban bao luxian menglie kaihuo 向刘少奇的“专家”办报路线猛烈开火), it presents a sustained argument for new forms of grassroots journalism. Sporadic efforts to give the proletariat a voice in the Chinese newspaper system date back to the 1940s. Both in Yan'an and in the early 1950s, the CCP had encouraged the cultivation of “worker-peasant correspondents” (gong-nong tongxunyuan 工农通讯员), an institution originating in the Soviet Union.Footnote 39 These attempts to involve the proletariat in Chinese socialist journalism, however, had failed to change the basic conventions of CCP newspaper practice. Journalism, so the article maintains, remained an essentially top-down practice controlled by the Party's propaganda system, which had utterly failed the test of the Cultural Revolution. “Lu Qun” demands a new approach to implementing the mass line in journalism: “Without this line, it is impossible to guarantee the correct political direction of the Party papers, impossible to realize the Party's leadership of the press, impossible to accomplish the political task of the Party papers; without this line, the newspapers cannot become the eyes and ears, the tongue and throat of the Party, cannot become the bridge and the bond between the Party and the masses.”Footnote 40 Mass involvement in the entire journalistic process, from news collecting to the writing of articles and editorials, would be essential for both the papers’ success and the proper functioning of the Party itself.

But what is the benchmark of mass involvement in journalism? It is in their answer to this crucial question that the article's author(s) venture onto new terrain:

Marxism-Leninism Mao Zedong Thought has always held that a proletarian party paper must not only rely on the masses of workers, peasants, and soldiers for its making, but the judgement and criticism of the papers’ correctness and quality should also be made by the worker-peasant-soldier masses. Only if a paper is endorsed and approved by the masses of workers, peasants and soldiers can it count as a truly revolutionary newspaper.Footnote 41

This proposition, offered in the article's final sentence, effectively cuts out the Party altogether. It turns a top-down system into a bottom-up system – a radical inversion of existing practices. The ultimate source of a newspaper's legitimacy is no longer its endorsement by the hierarchical administrative system of the party-state, but rather “approval” from the masses, from the grassroots itself. It is up to them to convey (or withhold) authority to the press. In a sign of how far the article pushes its argument, “Lu Qun” attributes what is presented as a commonly agreed principle (“has always held”) to “Marxism-Leninism Mao Zedong Thought,” but fails to provide a more specific source. In a rhetorical environment ever eager to invoke Chairman Mao's utterances as a source of support, the article's failure on this occasion to come up with a suitable quotation indicates that the call for popular legitimacy, and the denial of the Party's authority, was pushing the boundaries of the discursive terrain. The article advocates a journalistic landscape without the monitoring framework of the propaganda apparatus, a self-regulatory system of news production originating from the masses and addressed to the masses. How would such a radically new system look in practice?

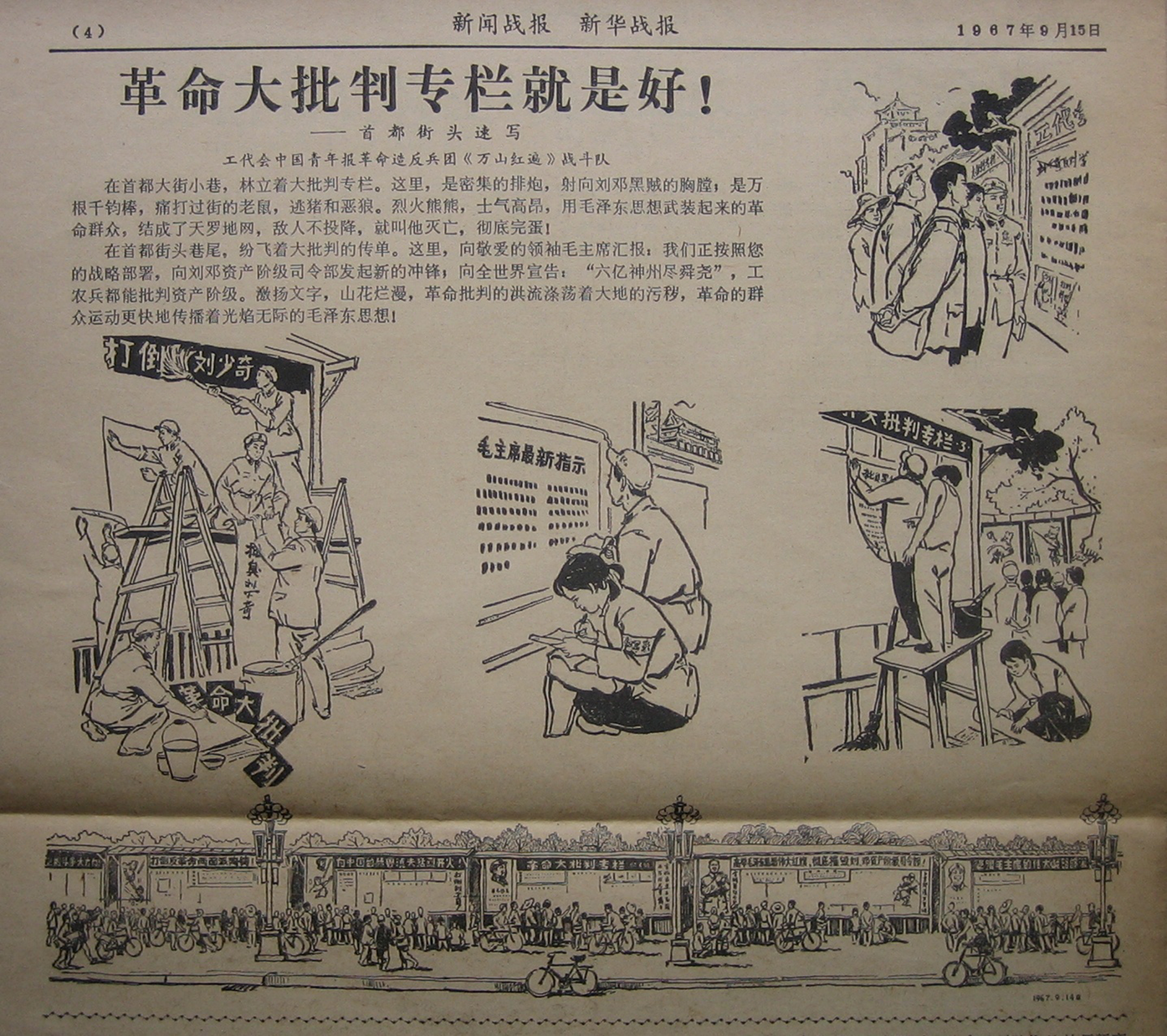

The closest equivalent of the media landscape envisioned in the article could be found, in fact, in the wallposters that had provided the model and the source of legitimacy for the earliest xiaobao. The Red Guard papers were clearly aware of this kinship, and the metadiscursive publications contain many reflections on dazibao and their function within the Cultural Revolutionary information ecosystem. Issue 17 (15 September) of Xinwen zhanbao portrays the ideal of mass involvement in this new ecosystem with a set of five illustrations that depict the discursive practice of wallposters (see Figure 1). The illustrations, which take up the top half of the issue's last page, render with much liveliness all the stages of wallposter production. In the top most picture, workers, a peasant (identified by his straw hat) and soldiers read a denunciation of Liu Shaoqi – his name is crossed out, a common practice in wallposters. The second picture shows what are presumably Red Guards in PLA uniforms pasting new posters to a wall. The central image depicts two Red Guards studying the latest instructions from Chairman Mao and copying them into notebooks, possibly to reprint them in the Red Guard papers. The image to the right shows the masses writing new posters. The grand panorama at the bottom presents the masses, who have acted as writers and producers of wallposters in the pictures above, now in their role of readers. Along a grand avenue that suggests Chang'an Boulevard 长安街 in Beijing, they read and avidly discuss the latest wallposters, whose layout, incidentally, resembles those of the Red Guard papers (note the Mao posters to the left of the “mastheads”). The medium of wallposters, then, signals a route to bridge the gap between writers and readers, between the producers and consumers of journalism. What is notably absent in the collage is any sign of institutional authority, a system of controls or approval, of powers intervening in the masses’ journalistic project.Footnote 42 The flat hierarchy presented in the idealized depiction of the wallposters levels the field not just by erasing the difference between writers and readers but also by imagining an organic flow of information that is horizontal rather than vertical, as the wide-angled panorama of the final image drives home visually. Yet while wallposters had become an important segment of the Cultural Revolutionary media landscape, they were not mass media. Their mode of dissemination entailed a necessarily limited scope. This is where the crucial difference between wallposters and xiaobao lies.

Figure 1: The Revolutionary Great Criticism Wallposters are Excellent!

Source: Xinwen zhanbao 17 (15 September 1967), 4.

The quasi-autonomous nature of wallposters, their obvious strength in the Red Guards’ eyes, was checked by their limited reach, a weakness the Red Guard papers compensated for. To justify similarly flat hierarchies and, accordingly, the journalistic autonomy inherent in a true grassroots press, however, required a more robust legitimation. In spite of the Cultural Revolution's anti-establishmentarian character, including Mao's call to “bombard the headquarters,” both Mao and the remnants of the Party apparatus had hesitated to hand over power completely to the radical mass organizations at critical junctions such as the insurrections of the “January storm” that toppled provincial Party committees nationwide. This hesitance had also left the boundaries of the Red Guard papers’ autonomy in a state of flux.

It is in an effort to define the proper scope and the basis of the Red Guard press's legitimacy that Xinwen zhanbao published, in issue 19 (28 September), an unusually eloquent and boldly argued article with the title “In praise of the Red Guard newspapers” (Zan hongweibing bao 赞红卫兵报).Footnote 43 Making a case for the Red Guard papers and their permanent place in a post-Cultural Revolutionary PRC, the article is among the most radical proposals emerging from the metadiscursive papers. It begins with a brief history of the Red Guard papers that invests them with the utmost amount of symbolic legitimacy but then quickly turns to the question of mass involvement in journalistic practice by invoking Mao Zedong: “With our newspapers, too, we must rely on everybody, on the masses of the people, on the whole Party to run them, not merely on a few persons behind closed doors.”Footnote 44 Mao's call for popular involvement in newspaper making, taken from his widely transmitted 1948 conversations with journalists at Jin-Sui ribao 晋绥日报 (Jin-Sui Daily), is rhetorically juxtaposed to the idea of news professionalism, attributed to Liu Shaoqi. Surveying the history of Party journalism since 1949, the author(s) conclude that the Chinese press has consistently repressed Mao's demands and favours Liu's line. Until the appearance of the Red Guard papers, that is:

The little generals of the Red Guards have never studied the “science” of journalism, they know nothing about the “five Ws” and the “eight factors.”Footnote 45 But they are warriors in the revolutionary struggle, storm troopers of the Cultural Revolution, each of their pens is a sword directed at the enemy, every single one of their papers is a battleground. The little generals of the Red Guards live among the masses, they have the broadest mass base, their newspapers carry out the mass line in the most thorough way. The major problem that remains unresolved after more than a decade – the detachment of those doing the reporting from those doing practical work – has been finally overcome in the Red Guard newspapers.

The article effectively links mass involvement in the process of newspaper making – the mass line in journalism – with the specific needs of class struggle. The Cultural Revolution itself had been defined from the outset as an instance of acute class struggle. Rather than withering away in a socialist nation, the bourgeoisie had regained momentum through “those in authority taking the capitalist road” (zou zibenzhuyi daolu de dangquan pai 走资本主义道路的当权派).Footnote 46 The accordingly intensified class struggle was now concentrated in the cultural realm, hence the need for a cultural revolution. In the PRC's political imaginary, the press is of course a crucial subsector of the cultural realm, the nation's newspapers becoming the very battleground on which the struggle between the two lines is waged. The article highlights this reasoning, noting that the Red Guard papers are not just the “warriors” and “storm troopers” of the Cultural Revolution, but “a battleground.” The newspapers, journals and pamphlets published by mass organizations all over the country, all hundreds and thousands of them, play a most crucial role at the very centre of the political maelstrom engulfing the nation.

The big question, then, is: are the Red Guard papers more than a transitional phenomenon, a convenient but momentary tool? In other words, would the Red Guard press have a permanent role to play in the post-Cultural Revolutionary nation? The authors’ answer, in the article's final paragraph, expands on the line of reasoning outlined above and is clearly in the affirmative. The Party press had comprehensively failed as a bulwark against attacks from the class enemy, and only the Red Guard papers were able to defeat the enemy. The Red Guard papers, consequently, would be needed in the future, for the same reason and purpose: to guard against future threats to the socialist system. The article concludes with the paean:

With their resolute and courageous action, the Red Guard newspapers have criticized the bourgeois, revisionist news line in a most thorough way. This is a great revolution with mass involvement on a scale unprecedented in the history of the proletarian press; it is a new victory for Chairman Mao's news line. The Red Guard newspapers have made a tremendously useful and valuable contribution to the experience of the proletarian press, a contribution that deserves to be seriously studied and explored by every revolutionary news worker. Let us loudly and with revolutionary enthusiasm praise this great new thing of historical significance, let us loudly and with revolutionary enthusiasm praise this great innovation in the history of the proletarian press!

Quite apart from its self-congratulatory prose, the article aims to cement the Red Guard papers’ permanent place within the Marxist pantheon and within the public sphere. It is because of its practical value, its “contribution” (gongxian 贡献), that the Red Guard press demands to be recognized as an indispensable part of any future arrangement of the Chinese public sphere. Implicit in this proposition is the notion that the Red Guard papers were able to fulfil their mission not in spite of their standing outside the traditional propaganda apparatus, but precisely because of their essentially autonomous nature. Situated outside the Party press system, they serve as a check on a system susceptible to hostile attacks. Put differently, their very grassroots nature, their immediate and organic connection with the popular masses, permit the Red Guard press to claim legitimate powers of oversight over the Party press – an essentially undemocratic medium that is, therefore, prone to failure. Their radical struggle against Chairman Mao's enemies had, in the final consequence, led the Red Guard papers to what appears to be a truly a promethean position.

Conclusion

“In praise of the Red Guard newspapers” was published at a critical juncture for the mass organizations and their publications. By autumn 1967, both were under intense pressure from a central leadership increasingly irritated by the mass movement's erratic course. The Wuhan Incident had initiated one of the most radical phases of the Cultural Revolution, but by August 1967, the Cultural Revolutionary left was in retreat.Footnote 47 Factional struggles had turned increasingly bitter and divisive, and once the political winds turned against the most radical elements in the leadership, the Red Guard press came under siege as well. Hundreds of papers across the nation ceased publication. The article was a bold proposition but also a defensive move, an attempt to carve out a permanent role for papers of its kind in an increasingly precarious environment. As it turned out, it was also a last hooray. Like so many of its peers, Xinwen zhanbao ceased publication after the issue in which “In praise” had appeared.

The closure of countless publications run by mass organizations was a rejection of the Red Guard newspapers’ model, but, paradoxically, also a confirmation of the validity of the reasoning presented by “In praise.” Mao Zedong, too, had recognized that if thought through to its logical conclusion, the radical position of the Red Guard press and its rejection of any external oversight would eventually challenge the Party's monopoly on power. This conundrum was of course not particular to the Red Guard press but pertained to the Red Guard movement as a whole and in fact to the philosophical underpinnings of the Cultural Revolution itself. The Li Yizhe 李一哲 group famously reached similar conclusions in 1974, and contemplation of the movement's liberatory potential inspired a generation of dissident thought.Footnote 48 Heterodox ideas also drove the radical thinkers behind Shengwulian 省无联, one of the local groups that resisted orders to dissolve in 1968. As Wu Yiching has shown, groups across the nation sought recourse to Mao Zedong Thought to justify their radical positions.Footnote 49 But when the Cultural Revolution threatened to devour its own creator, he turned against it. The closing of the vast majority of Red Guard publications became a prelude to the demobilization of the Red Guards a few months later, in August 1968.

The radical position articulated in “In praise” but supported more widely in the metadiscursive Red Guard papers was complicated by another problem, an inherent contradiction of the Red Guard press. While proposing truly bottom-up forms of journalism and rejecting outside oversight, papers such as Xinwen zhanbao were themselves close to, and likely in close contact with, the radical wing of the Cultural Revolution leadership. While there is no direct evidence of interventions from Jiang Qing and others, Xinwen zhanbao, as noted above, had ties to the very apex of Cultural Revolution politics through its own institutional affiliations. Traces of such connections surface in the positions and rhetoric of Xinwen zhanbao and many other Red Guard papers. These ties call into the question not just the grassroots nature of Xinwen zhanbao but also the top-down versus bottom-up binary itself, constructed by the papers in their deliberations on the nature of the press. As Denise Ho argues in the context of class education exhibitions in the 1960s, grassroots organizations were susceptible to guidance from above, and information flows during the Cultural Revolution were decidedly more complex than simple bottom-top and up-down patterns suggest.Footnote 50 While we do not know to what extent the positions and propositions of “In praise” were coordinated or inspired by the more radical elements of the Cultural Revolution left, these entanglements at least suggest that the radical idea of a Red Guard press free from any form of oversight needs qualification.

The Red Guard press's claims for a quasi-autonomous position within the Chinese socialist system also leave unaddressed the question of Chairman Mao's authority. The radical propositions of “In praise” draw on Mao Zedong Thought, and the Chairman's charismatic authority was crucial to Cultural Revolution politics, often replacing institutional or bureaucratic forms of legitimacy. Yet the ultimate authority of Chairman Mao stands in tension with the vision of a truly bottom-up and autonomous press. It is also here that we may observe remnants, conscious or not, of the Party's well-known claim to represent “the people,” a fundamental Leninist tenet.Footnote 51 Renmin ribao was “the people's paper,” all the while functioning as the CCP Central Committee's official mouthpiece – a contradiction which did not exist in the CCP's own definition but became one once the inner-Party consensus collapsed at the start of the Cultural Revolution. In this sense, the Red Guard papers’ claim to speak for the masses, truly and directly, harbours the same built-in tension centred on the problem of how to define the “people” or “masses” as well as their agency. “In praise of the Red Guard newspapers” sidestepped these questions. Yet in doing so it adopted a radical position, outlining the vision of a public sphere in which the Red Guard press would play an important and in fact central role.

The author(s) of “In praise” did not go on to endorse the principles of a free press or of liberal freedom of expression. Little could be further from the minds of the militant partisan publications of the Cultural Revolution. As the current article suggests, they operated in and supported a public sphere that was decidedly illiberal in nature or what I have called “praetorian.” Rather than opening themselves to public reasoning, the central tenet of the Habermasian public sphere, their stated aim was the destruction of their enemy, rhetorical or otherwise. And yet, even with the qualifications noted above, their conscious evocation of their grassroots legitimacy led the Red Guard papers, or at least those of a more self-conscious, metadiscursive variety, to a position that must be called promethean: once launched on a path of rebellion, the limits of legitimate discourse were sent into permanent retreat, to the point where limits of any kind appeared to become illegitimate. This fundamentally paradoxical situation in fact characterizes the Cultural Revolutionary public sphere as a whole: the collapse of the Party press, of hundreds of established newspapers and journals, under a ferociously illiberal assault, which in turn gave rise to an anarchic chorus of autonomous pamphlets and grassroots publications, each claiming legitimacy precisely because of the fall of their predecessors. The demise, temporary as it turned out to be, of Leninist Party journalism gave birth to a cacophony of new, radical publics. With the limits of discourse in flux, these radical publics created an opening for thought experiments unheard of since 1949. The “small devils” had been liberated and were dancing in the streets.

Acknowledgements

This article and the ideas presented here were shaped at an Association of Asian Studies panel and the 2018 conference “Publicness beyond the public sphere.” I am indebted to Sebastian Veg, organizer of both events, and the other participants for their input and insights.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical note

Nicolai VOLLAND is associate professor of Asian studies and comparative literature at Penn State University. His work focuses on modern Chinese literature, print culture and Sinophone studies.