In this drawing, [Figure 1] a man in a top hat smokes a cigar while ordering a European soldier to point his gun at an Arab farmer. The farmer plows the fields, while bombs erupt in the background, blowing a group of domed buildings to smithereens. The same cigar-smoking man orders a dark-skinned soldier to fire on a group of striking workers on a cobbletone street. Finally, something happens. Top hat flying, the rich man runs for his life. The men he had ordered to fire on one another have turned their guns on him, as the crowd cheers them on, safe. This cartoon appears in the Journal des Peuples Opprimés, from March 1934.Footnote 1 This was the periodical of the French section of the League Against Imperialism, and it depicts the logic of this organization clearly and without a word.

Figure 1. Cartoon from Journal des Peuples Opprimés (March 1934).

The League Against Imperialism (LAI) was founded in 1927 at a meeting in the Palais d’Egmont in Brussels, and was active for ten years. 174 people attended the 1927 Brussels congress, representing 134 organizations from 34 countries. The LAI’s aim was to coordinate the various movements against imperialism and capitalism, making up a united front against a common enemy. The LAI was one of many overlapping anticolonial groups and networks crisscrossing the globe. But it stood out for its members’ extraordinary attempt to coordinate myriad anti-colonial groups with the Communist movement in Europe. This began in earnest with the initial meeting in February 1927. For the next year, members corresponded and worked to build up local sections in several countries. In summer 1928, the Communist International shifted its strategy of a united front, accommodating to communists and non-communists it considered to be strategic partners in the struggle against capitalism and imperialism. Instead, the LAI’s executive committee was instructed to expel social democrats, ‘bourgeois nationalists’, and others who would not facilitate the sharpening of class consciousness and the organization of communist trade unions and parties. In 1933, the German police raided the offices of the LAI in Berlin, and the headquarters moved to London. This disrupted the organization’s activities as had the narrowing of its mission due to the Comintern’s shift in strategy in 1928. Nevertheless, the LAI sections continued their political activities within the most powerful European empires of the period: Britain and France. The British and French sections continued to publish material, organize meetings and protests, and correspond with other groups both in their respective countries and across the world. The organization continued operating from its headquarters in London, and national sections continued to print materials and meet, until the group was quietly dissolved in 1937.

One of the most ambitious attempts to re-order the relationship between imperialism and capitalism before the Second World War came from the revolutionaries of the future Soviet Union. Following the British liberal J.A. Hobson’s influential text, Imperialism: A Study, V.I. Lenin and Nikolai Bukharin, among others, articulated a theoretical and revolutionary analysis of the relationship between ‘imperialism and the world economy’.Footnote 2 After the Second World War, leaders in the Caribbean, South America, Africa, and Asia attempted to re-order the relationship between capital and empire in two main ways. First, leaders of new postcolonial states saw this as an integral part of the process of formal decolonization. Second, states in the Caribbean and South America attempted to break the stranglehold of American control in the economies of the Western hemisphere which had achieved formal independence a century or more before. Just as the twinning of states and peoples proved difficult in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, the extension of freedom and prosperity wholesale from that equation proved more difficult still for states decolonizing during the Cold War.Footnote 3

By the 1970s, a re-organization of power by way of resource use and international trade emerged as a solution to the problem of unfinished decolonization. Historians have recently shown how this took place, in studies of the ‘oil revolution’ of 1973–74 and the proposal for a New International Economic Order made at the United Nations in 1974.Footnote 4 In addition, recent histories of the transformation of international order in the twentieth century have continued to examine the dichotomy between high-politics-from-below, and mass-politics-from-above.Footnote 5 A synthesis of these vantage points suggests that at every juncture, the centre of gravity for global transformation has teetered between the spaces of international organizations and the spaces of mass politics. The relationship between the two was central to discussions of making new worlds in the three decades after the Second World War. For example, historians have approached the Cold War and decolonization from diplomatic and state archives as well as via the popular press and rumour.Footnote 6 This article draws on this framing of inventive forms of state-making and global re-ordering to examine the LAI as an idiosyncratic and short-lived international organization, whose members aimed for that body to become a mass movement. This mass movement was meant to disrupt the relationship between imperialism and capitalism by spurring workers around the world to coordinate their struggles for trade unions, political independence, land, and more.

Nested inside this international project was a logic for synthesizing forms of difference into a global vision. Rather than facilitating or immediately re-organizing global production, consumption, or trade, the LAI’s members sought to disrupt it. The road to an anti-imperial future first required the global and systematic sabotage of the joint operations of imperialism and capitalism. This would be achieved by drawing European and colonial workers into a coordinated effort to interrupt the expropriation of land, the exploitation of labour, and the control over transport and trade. The LAI’s form of anti-imperial politics foresaw an international organization to address these global problems, while working-class people’s calls for action showed the specificities of how these rather abstract problems affected everyday lives. Members attempted to forcefully articulate the relationship between foreign rule and material dispossession linked by a closed, unequal, and interconnected system of exchange. They did this in the organization’s publications and in between the conference rooms of a Belgian palace and an open square in Palestine. These delegates represented free nations that did not yet exist under international law. Their organizations were under siege and de-centralized from almost their very inception. This kind of disjointedness at the helm of a project of global transformation is not unprecedented, but it is useful. In this article, I show how members of the LAI fused the form of an international organization with the content of mass politics by analyzing their speeches, resolutions, pamphlets, and performances. This attempt did not, in the end, succeed as they had hoped, but its articulation allows us to think the international organization at the limits of both the nation and the international organization itself.

Historians of interwar anti-imperialism and anti-colonialism have demonstrated the explosion of political activity and exchange that characterized the 1920s and 1930s on every inhabited continent.Footnote 7 These concerns also animate the interwar conflicts at the heart of Giorgio Poti’s article in this issue, on the dispute between Great Britain and Egypt over territory in Sudan after the Ottoman defeat in the First World War. The League of Nations functioned in the realm of governance, law, and arbitration – a far cry from the politics of solidarity and aspirational gestures towards governance made by would-be statesmen and fellow travellers in the LAI, but Poti’s emphasis on an anti-teleological reading of interwar conflict suggests historians read anti-imperial and imperial politics as part of the same historical transformations in these years. Participants were at once grasping at normative statehood (naming ‘national independence’ as their aim) and rejecting the apparatus by which it was upheld (the prevailing system of international order). Bogdan C. Iacob shows in this issue how experts in malariology and disease control from Eastern Europe produced knowledge that contested Western worldviews. Cindy Ewing’s article in this issue shows how, in the wake of the Second World War, the Arab-Asian group at the United Nations was similarly a site for neither uniformity nor consensus, but rather a demonstration of the tension between common goals and a shared strategy. Many international organizations produced the appearance of a coherent politics and call to action, but upon closer examination, held up difficult contradictions. Members of the LAI took up an end to imperialism as their collective aim and named the nation-state as the goal of their organization. The world they anticipated was not quite the world that came to be after formal decolonization in the 1940s–1960s.

Recent work has compellingly narrated the emergence of the world economy as both material condition and analytic category in the twentieth century.Footnote 8 The integration of more and more parts of the world into a circuit of circulation, exchange, and increasingly, exploitation coincided with the expansion of European and later, US empire and the creation of trading blocs inside and between these imperial zones of control.Footnote 9 Patricia Clavin has shown how the crises of the 1920s prompted the League of Nations to take on a responsibility its architects had not intended: the management of the world economy and the safeguarding of the conditions for capitalism’s survival.Footnote 10 This intervention, along with Susan Pedersen’s work on how the League of Nations preserved imperial control over territories outside Europe, shows that at the level of the interwar period’s most influential international organization lay the entwined missions of the preservation of capital and empire.Footnote 11

The LAI was not exactly an expansive internationally-run organization, disconnected as it became from the core functions of the Comintern after 1928. Nor did it function with the strictures and privileges afforded by international law and the endorsement of world powers, like the League of Nations. It was an international organization insofar as it brought together representatives of various places and projects, many national in scope. Some members, like the representatives of the Comité de Défense de la Race Nègre or those of various trade unions, operated inside national or imperial contexts but articulated their aims in terms of a political subject distinct from that of the national community.Footnote 12 The study of the international organization as a discrete object of study has exploded in the last decade, with critical scholarship on its origins, operations, political worlds, and limitations buttressing an even wider field of scholarship on internationalism more broadly.Footnote 13 This article examines the LAI in its capacity as a discursive space and political contact zone, two key aspects of international organizations that have been drawn out in recent work.Footnote 14 As a discursive space, it was a site for working through problems and concepts that emerged in members’ attempt to articulate their particular struggles to one another. As a contact zone, it was a site to establish relationships of friendship and solidarity, which at times succumbed to political conflict. Taken together, these aspects allow us to examine how activists in the interwar period used depictions of the world economy and its specific, material effects to make a case for a global struggle.

Historians have largely written about the LAI as part of larger narratives about the political currents that characterized the 1920s and 1930s, including anti-colonial nationalism, international communism, Black internationalism, and policing, with many of these stories themselves intertwined.Footnote 15 Indeed, the LAI itself was a site for the interaction between individuals and organizations that worked to merge what might otherwise appear as entirely distinct movements. In the last decade, historians have used organizations like the LAI as an opening to explore the particularities of this unprecedented confluence. Recent studies of the LAI have foregrounded the complex political networks, specificities, and long afterlives of the questions that arose at the 1927 Brussels Congress and the subsequent decade of activity carried out by LAI members. In the introduction to their edited volume on the organization, Michele Louro, Carolien Stolte, Heather Streets-Salter, and Sana Tannoury-Karam argue that the LAI is an object of study in its own right because of its role as a meeting-place for people with strikingly varied experiences and politics, for its impact on many influential world leaders, and because it is a way into understanding the frenetic internationalist moment of the years between the First and Second World Wars.Footnote 16 Previous studies focused on the LAI include Fredrik Petersson’s two-volume account of the organization, which examines Willi Münzenberg’s role and the operations of the group from 1925 to 1933, informed by extensive research in the archives of the Communist International. Jean Jones’s 1996 history of the British section details the activities of the section and relationships with other groups on the British left.Footnote 17 Studies of well-known figures involved in the organization for even a brief period, such as Jawaharlal Nehru, Soong Ching-ling (Madame Sun Yat-sen), and Josiah Tshangana Gumede, have noted the importance of this milieu for the development of their political outlooks.Footnote 18 Biographies of the LAI’s two prominent leaders Virendranath Chattopadhyaya and Willi Münzenberg detail their travels and work with this organization, and in the wider world of European left.Footnote 19 This work has largely focused on the operations of the LAI in the years 1927–33, when the German headquarters of the organization were active, and when, via Münzenberg, the group hewed closer to its original role as a Comintern hub and agitational arena. This article builds on this increasingly comprehensive account of the LAI’s members, operations, and networks in order to examine the relationship between political independence and the world economy as a critical aspect of the organization’s political outlook. This argument draws analytically from the emphasis on the ‘futures past’ of the early anti-colonial and socialist movements of interwar period as well as the emphasis on the control of resources and economies urged by historians of the later decades of twentieth century’s long and incomplete decolonization.Footnote 20 Shifting focus away from the centres of the European communist movement in Moscow and Berlin to the belly of the imperial beast in London and Paris, this analysis begins with the initial framing of the LAI’s international aims and leads from that brief coherence to the ultimately quixotic enactment of the organization’s mission among workers, activists, and mere passersby.

I examine this aspect in its founding moment (when the openness of Comintern policy allowed the confluence of tendencies in the anti-imperialist movement that would then move apart), as well as in the centres of the two most expansive European empires of the period: Britain and France. These spaces, I argue, allow us to examine a site in which activists worked through the relationship between political independence and control over land, labour, and capital, under the auspices of an international organization with an explicit aim to carry out mass struggle. This occurred, as I show, via members’ pulling together the form of the international organization (with aims on a global scale) and calls to action from below (which attended to the specificities of dispossession in individual places). This article contributes to the growing field of global intellectual history by looking closely at a varied set of archival sources drawn from an international organization and asking the same question of all of them: how were the worldviews represented here supposed to translate to global political transformation? Below, I examine this question through the way delegates mapped the contours of a global problem at the first meeting in February 1927, the translation of this vision into calls to action in memoranda, speeches, and pamphlets, and the forms of mass politics enacted and represented by the LAI in its final years.

Mapping the contours

As an organization, the LAI functioned as the periodic, institutionalized, and largely aspirational meeting place for activists and dissidents concerned with anti-imperial politics in Europe, international in composition and in scope but crucially not comprised of the representatives of sovereign states, discrete and bounded. But in texts produced at the highly publicized conferences of its early years, or for dispatch to other organizations, or for dissemination to the public, the LAI articulated a form of internationalism that sought to undercut the authority of the established international order. For the LAI, this was made possible, and indeed, presented as necessary, via the architecture of the international organization. In this context, the LAI’s geographically and racially diverse membership, its conscious mirroring of the League of Nations in form, and its origins in the Comintern’s political world allow us to examine the interstices of the stark ideological divides that otherwise marked the period’s political alliances and disagreements.

The LAI was charged by its members at the February 1927 Brussels Congress with coordinating the struggle against both capital and empire. It failed in its mission to bring about an end to an imperial world, but what persisted in the decades that followed the abortive projects of international re-ordering of the 1920s and 1930s was a persistent vocabulary for projects of liberation, even as many of them found their form in the borders of a nation-state and the bounds of the national economy, which in many cases had been inherited from colonial regimes. When we apply this to the materials that the LAI left behind, we can read members’ attempts to describe and denounce the specifically economic role of imperialism.

Observers and participants in the LAI’s 1927 founding congress immediately identified it as the ‘real’ League of Nations.Footnote 21 The list of attendees and organizations identifies delegates from the following places: the United States, Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Peru, Venezuela, ‘Central America’, Colombia, China, India, the ‘Dutch East Indies’ [Indonesia], Korea, ‘Indo-China (Annam)’, Persia, the Philippines, [A. Alminiana, from the Filipino Association of Chicago], South Africa, ‘West Africa’ [Sierra Leone], ‘North Africa’ [Lamine Senghor, from Senegal, representing the Comité de Défense de la Race Nègre], Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Germany, England, France, Holland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Italy, Syria, and Palestine. The Comité de Défense de la Race Nègre (CDRN) was headquartered in Paris, and listed under a subheading ‘colonial organizations having their headquarters in Paris’, along with the Kuomintang Section in France, the Constitutional Party of Indochina, and the Intercolonial Union. The congress produced 16 reports on various places, and the main surviving collection of the LAI’s documents at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam also contains several pamphlets, presumably written by associated members. These include treatments of the Japanese occupation of Korea and the situation in Persia. In the programs of the congress, delegates were listed under the countries and organizations they represented, and not necessarily their places of origin. For example, Manuel Ugarte, an Argentinian writer and socialist, was listed as a representative of the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico.Footnote 22

Organizers adhered to the formality, structure, and aesthetic of the international meeting, with delegates representing different places and organizations gathering over days to deliberate over resolutions, attend afternoon teas, and pose for photographs. In the years that followed, this capstone moment for the organization was followed by the establishment of national sections in several countries, the public demonstration and mass meeting, and the proliferation of published material for a wider readership. LAI members explicitly aimed in 1927 to use the structure of an international organization to facilitate the political agitation of working-class people in their home countries, in order to coordinate the disruption of the imperial/capitalist machine. They believed that failure to disrupt capitalism would worsen the ongoing suffering of the world’s peoples and, most urgently, bring about another world war. Stirring up awareness of the connection between the project of imperialism and the profit gained by European and American capitalists was key to this disruption.

The Comintern’s broadest institutional framing of this relationship followed from Lenin’s formulation of ‘imperialism: the highest stage of capitalism’. This argument emphasized the relationship between the expansion of European control over Asia and Africa in the nineteenth century, and the persistence of control of those territories in the twentieth, by describing how ‘capitalist countries’ exploited the land, labour, and natural resources found there.Footnote 23 Besides the European empires that dominated most of the world, Lenin and communists after him described the ‘semi-colonies’ of Latin America as subject to the imperial control of the United States of America.

The Comintern set the stage for the LAI’s establishment by laying out the global and fundamental relationship between the economic system of private ownership and profit and the political system of foreign rule and the material dispossession it engendered. The LAI’s informal leader and Comintern functionary Willi Münzenberg had begun a ‘Hands Off China’ campaign in Germany in 1925, a response to the crackdown against Chinese workers in Shanghai by British police in May of that year. The idea for an ‘all-encompassing’ anti-imperialist meeting came from representatives of Chinese trade unions at the 1925 ‘Hands Off China’ congress in Berlin, and over the next two years, Münzenberg worked to establish this as a priority for the Comintern.Footnote 24

The loss of land and the exploitation of labour were some of the starkest ways in which colonized people experienced the imperial expansion of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Through the LAI’s internal reports as well as through their appeals to the public, members described and emphasized how this loss affected various aspects of life in the colonies. At the Brussels Congress in February 1927, several delegates took the opportunity to share these accounts with one another and an eager press. Among these delegates were Josiah Tshangana Gumede from the African National Congress, the Indonesian activist Mohammad Hatta, Sen Katayama from Japan, José Vasconselos from Mexico, the Guadeloupean lawyer Max Bloncourt, and Jawaharlal Nehru from India. The delegates chose a general council and planned to found sections of the LAI in their home countries when they returned. For the next year, many members would plan meetings, print and distribute materials, and attempt to grow the organization into something that could fulfil the potential of the energetic founding congress, by soliciting support from as varied a slate of possible participants as they could muster.

Rather than an internationalism grounded in the sovereignty of a state, or the popular mandate of successful revolution, or the rubber stamp of an election, or the mantle of international law, the internationalism enacted at the Brussels congress was one held together by the shared condition and discourse of subjection. The delegates at Brussels who did speak on behalf of their homelands were often members of dissident organizations or political parties that had uncertain levels of support or influence among the people they claimed to represent, and indeed, no interest in behaving as though there were a broad mandate back home for their participation.Footnote 25 Among these delegates were E.W. Kim and Kim Pob In from the Korean students associations of Paris and Columbia University, A. Alminiana of the Filipino Association of Chicago, and E.A. Richards from the Sierra Leone Railwaymen’s Association.Footnote 26 Claims were made at the congress on behalf of trade unions, communist and socialist organizations, and anti-colonial nationalist organizations, as well as by individuals speaking on the basis of their participation in politics, arts, and letters, such as Henri Barbusse, Manuel Ugarte, and Diego Rivera. The way imperialism appeared and acted on people living and working around the world was clear; a great deal of the material produced by the LAI was dedicated to demonstrating the adverse effects of foreign rule and economic exploitation. They reminded one another of the need to act in advance of the next ‘imperialist’ world war. Footnote 27 On the one hand, speeches and printed materials contained a concrete explanation of the structural relationship between each instance of violence, dispossession, or suffering discussed at the congress. On the other, the ‘particular conditions’ of each place were both evidence of the specificity of the phenomena of imperialism and capitalism, as well as the very means by which a universal struggle could, and should, be waged against both at once.

The structure of the various speeches and reports that survive from the 1927 congress is strikingly similar, which we may attribute to the uniformity produced in the agenda of a conference, the directives of the organizers, or an understanding amongst participants.Footnote 28 None of these explanations negate, however, the result for the reader and, perhaps the listener too, of the repetition of similar reports from every inhabited part of the world, attributed to global developments. At Brussels, delegates began with a sketch of the situation in their home country, or the place from which they were reporting. Indeed, national origin was not always the basis of the claim to speak; they came from the places where they were living or were studying, representing student groups, trade unions, political parties, and other organizations. Nonetheless, an explicit purpose of the congress, and of much of the political activity of the LAI in the decade that followed, was focused on getting information about a particular place to the ‘wider world’ in order to generate support for struggles in those places and make clear the relationship between strife in one place and a global system.

The North Africans at Brussels, for example, provided a stark account of how their political freedom was tied to material expropriation. Footnote 29 Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia were represented by the organization Étoile nord-africaine, which had been founded by Algerian members of the French Communist Party (PCF) in 1926. Footnote 30 The ENA was led by the Algerian nationalist Messali Hadj, and put forward a resolution at Brussels that began with an overarching description of French imperial governance, and then broke down into specific sets of demands by nation, including calls for the complete independence of Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. The report on the North African situation listed the following grievances: the expropriation of land, the destruction of Arabic schools, the control of movement, the military occupation, and the destruction of cultural and artistic life. Delegates also noted the hypocrisy of the French imperial ideology: ‘this expropriation is done, as always, under the sign of civilization’. Footnote 31 In the name of the ‘civilizing mission’ of the French, tens of thousands of ‘rebels’ had been exterminated, the majority of the rural population had been displaced, and that population was now being exploited for profit.

Delegates wrote that in Algeria, 2,800,000 hectares of the best land had become the property of Europeans by 1927, the land that ‘contained natural riches and was the most cultivable’. Meanwhile ‘the indigène families whose lands were expropriated had to sell their physical labour to the new landowners or emigrate to the urban centres’. Not ‘content with the expropriation of the indigenous population of Algeria’, the report continued, the ‘French instituted a system of political domination and destroyed the ancient forms of Islamic democracy that existed before colonization, maintaining only a caricature of these forms’. In response, the exploited and oppressed working people of Algeria would continue the ‘permanent fight against imperialism, to free themselves from this yoke and win independence’.Footnote 32

North African delegates were keen to show the ubiquity of the large-scale expropriation of land across the region, and how it transformed native people’s relationship to their livelihoods. They wrote that in Tunisia, out of 2,100,000 hectares of workable land, 37,000 European settlers occupied 700,000 hectares chosen from among the best land. The rest of the 2,100,000 hectares for 2,200,000 Tunisians, ‘among whom is a stratum of landowners, who exploit the peasant masses of Tunisia the same way as the colons’.Footnote 33 In Morocco too, the situation was similar, and there, despite the ‘regime of terror that reigned over [the country], labour unions had begun to emerge’. With such encouraging signs from the workers of the region, with the ‘help and fraternal welcome of the workers of France’, delegates were confident the fight for independence in North Africa could continue and grow. Messali Hadj concluded his statement to the congress with a simultaneous appeal to the past, present, and future: ‘About our evolution, Sirs, not only do we belong to and are the descendants of an old civilization that you all know of, but we are not at all indifferent to civilization or modern progress. […] This is why, Sirs, we affirm before the entire world that we are capable of leading the destiny of our country and securing our political and social life’. Footnote 34 For Hadj, by undermining the civilizational logic of the French imperial mission, showing the reality of French dispossession of North Africans and the proof of their politicization and capacity to resist, the case could be made (not to the French establishment, but to fellow anti-colonial activists) that North Africans were already on the path to realizing an anti-imperialist future. The North African delegates argued for the urgency of the struggle by forcefully demonstrating how far the French had expropriated land and labour.

A longer history of dispossession was also key to the LAI’s articulation of the origins of the world economy. It was this long history that members argued joined together the various groups they hoped to spur to mass mobilization in their respective home countries. The Senegalese activist Lamine Senghor attended the Brussels Congress as a representative of the Comité de Défense de la Race Nègre (CDRN), an organization based in Paris.Footnote 35 Senghor was a member of the Parti communiste français (PCF) and a former soldier, a veteran of the First World War. In a speech at the Congress, he outlined the relationship between the enslavement of Africans in the past, and the continued exploitation of African labour in the present. ‘Slavery has not been abolished’, Senghor argued: ‘It has been modernized’.Footnote 36 The enslavement of individual African people, Senghor argued, was replaced by the wholesale exchange of African nations between Europeans, as control over the territories of the African continent grew after the Berlin Conference (1884–5), using the Agadir Crisis of 1911 as an example. In exchange for French control over Morocco and a resolution of the dispute that had originated in the port of Agadir, the French government allowed Germany control over parts of French-administered territory in Congo. Senghor drove home his argument by referring to this so-called resolution by pointedly asking in his speech: ‘Did [France] ask the Negroes of the Congo whether they wanted to be exploited by the Germans?’Footnote 37 As part of his critique, Senghor also rather sarcastically pointed out the persistence of democratic language in the political framing of an age after abolition: ‘[Slavery] we are told, has been abolished, and one might almost grant that the sale of slaves is forbidden, and that one can no longer sell Negroes to a white, to a Chinese, or even another Negro. But we see that the imperialists very democratically reserve the right to sell an entire Negro people to another imperialist’.Footnote 38 The ‘modernization’ of slavery thus resulted in the continued and entrenched oppression of Black people the world over. It was the exploitation of Black labourers that tied their present condition to a longer history of exploitation.

This argument was also made by a group of Black delegates in 1929 at the LAI’s Second World Congress in Frankfurt am Main, in the resolution ‘on the Negro question’. Delegates noted that ‘[the imperialists] are training black armies for the next war and are using black troops to suppress the struggles of European workers (France); and to conquer new areas for colonial exploitation’.Footnote 39 The resolution included in its demands specific items that addressed the racism experienced by Black workers in particular. The resolution also included universal demands such as a commitment to ‘the struggle against all racial barriers in the Trade Movement’ – a demand which included ‘the creation of a single all-including class international embracing the Trade Unions of all countries and all races’.Footnote 40 In this resolution, delegates also articulated a long history of capitalism and imperialism that predated the consolidation of European empires that occurred at the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote 41 Delegates specified: ‘the economic and political enslavement of the Negro peoples has extended over a period of 300 years which may be divided into three stages’.Footnote 42 The first period was that of ‘merchant capitalism, which stood everywhere for a system of robbery and the snatching of slaves, and marked the birth of the infamous African slave trade’. The second period was that of ‘industrial capitalism’ which ‘marked the beginning of the territorial division of Africa, and the capitalist exploitation of its resources through the exploitation of native labour power’. The third period was the ‘epoch of imperialism’ – defined for them as the period characterized by the ‘completion of the partitioning of Africa and the complete enslavement of its peoples’. This period is one in which merchant capitalism went global: ‘this period brought with it the intensification of the exploitation and oppression of Negroes in all parts of the world’.Footnote 43 Here, the delegates established the history of slavery and colonization both as central to the history of the world’s economy and situated Black struggle at the heart of the project started at the Brussels Congress.

As scholars of global history have pointed out, anti-colonial activists of many types used several ‘publicity strategies’ in the interwar years.Footnote 44 These strategies included correspondence, published material, and physical gatherings such as conferences and assemblies to influence the press and bring together the anti-colonial struggle with others, such as the growing international women’s movement. The ‘global public’ onto which this circulation mapped was ‘often driven from above and meticulously engineered to attract global attention’.Footnote 45 In the years that followed, the LAI sent missives and reports to other organizations, in the form of correspondence between members (in private) and in public, addresses published in their own and other periodicals, and memoranda to conferences of international participants.Footnote 46 The LAI also addressed the public they encountered in the streets, in the form of mass protests, large public meetings, or street theatre. In both these registers, it was not the discussion between delegates already committed to the cause that was at stake. Rather, this was part of the LAI’s mission to agitate around the specific issues of colonial repression and the exploitation of workers and channel that into a coordinated worldwide assault against capital and empire.Footnote 47

For the LAI, this attempt was carried out beyond the conference room and private correspondence in these addresses to sympathetic (or sometimes apathetic) audiences, who were the kinds of people who might be stirred to join the movement. In particular, the economic relationship between different types of workers in different places was a theme the LAI returned to time and again. Between Geneva’s great halls and the streets of Preston and St-Denis, the LAI calibrated its message about the interconnectedness of workers and the world economy to what they hoped to help along – the growth of anti-imperialist public opinion.Footnote 48

Calls to action

In order to turn the statements at the Brussels Congress into mass action, part of the assumption underlying the organization’s political activities was that European workers needed to be educated as to their shared plight with colonial peoples, and that colonial workers and peasants needed to be educated as to their political role in revolutionary change. In the LAI’s call for a mass movement at the first meeting, organizers had exhorted those delegates who could assemble, educate, and organize ‘workers and peasants’ to do precisely that, in order to establish a global movement: ‘The League, therefore, must explain the situation to the toiling masses [European workers] in order to mobilize them in a real struggle against imperialism in conjunction with the oppressed peoples’. Footnote 49 The British socialist George Lansbury, unable to attend the Brussels congress, had sent a message instead. In it, he had written: ‘I would like to bid my Comrades from Africa and Asia to be of good cheer. It is certain as the sun shines that Imperialism is doomed: it is doomed because with the rising of the working-class intelligence this imperialism with all its poisoned gas and disciplined armies, cannot overcome the boycott which it is within the power of the workers to enforce’.Footnote 50 In extending this hearty encouragement, Lansbury identified the relationship between class consciousness and the ability (and willingness) to interrupt the workings of imperialism. He went on: ‘[The imperialists] want trade, they want markets, and these they will never obtain by the measures they are adopting at present’.Footnote 51 He noted that anti-imperialists would need to ‘teach the workers not to enlist in National armies, not to manufacture armaments’.Footnote 52 The relationship between the war machine, imperial expansion, and the expansion of trade and markets were thus at the center of this analysis of the situation before the Brussels delegates. This was a common position among broad swathes of the liberal and left political spheres in the years after the war and would continue to resonate for decades. The repeated and simultaneous calls for workers to disrupt these operations formed the backdrop to the specific demonstrations of the sites of land expropriation and labour exploitation that anti-colonial nationalists from outside of Europe as well as metropolitan anti-imperialists would bring together in their call for mass mobilization.

The LAI also used media such as newspapers, pamphlets, and theatre to communicate the necessity of a worldwide struggle to workers in European cities, and thus transmitted news of anti-colonial struggles to its audiences.Footnote 53 Jonas Brendebach, Martin Herzer, and Heidi Tworek have shown that international organizations ‘used media from the start’ and these media themselves ‘spurred the establishment of international and transnational institutions’.Footnote 54 They contend that sometimes, activists chose to shift focus to mass media and the dissemination of information in the absence of a path to concrete political victories for their campaigns. Indeed, the LAI’s early aspiration to bolster a global revolutionary movement was thwarted within two years. This occurred because of the rending of the Brussels alliances by both the Comintern’s directives as well as the Labour and Socialist International, which pulled communists and non-communists in different directions. In the absence of a broad base of institutional support, it may have been that members felt the best course of action was an agitational campaign. Despite this, there is evidence that for the LAI, the circulation of newspapers and pamphlets especially rested on the idea of a public that was primed and ready to become politically active, even militant, once they learned the truth of colonial oppression. But this audience proved to be fragmented, circumscribed, and difficult to map effectively. As Valeska Huber and Jürgen Osterhammel have shown, the rise of self-determination as an agenda during first decades of the twentieth century was given specific political valence by way of an emerging ‘global public’, incomplete and elite-driven as it may have been. The ‘general criticisms’ against the old international order that emerged in the 1910s were transformed by tying them to concrete situations and circulating information about these situations through various media.Footnote 55

The League of Nations also produced an extensive range of documents for a public readership, including a pamphlet series which mirrors the LAI’s own. The League of Nations’ Information Section, for example, published such short explainers as a survey of the League’s operations, its constitution and organization, its economic and financial organization, intellectual cooperation, and political activities. Its pamphlets on specific places mapped onto the locales of the period’s flashpoints (from the League of Nations’ perspective): the mandates, Austria, the Saar basin, Danzig.Footnote 56 The LAI’s British series covered ‘China’s appeal to British workers’, ‘the war danger in Abyssinia’, ‘India and a new dictatorship’, and ‘Palestine’.Footnote 57 The French section published a series overall titled ‘dossiers on colonization’, included topics such as Madagascar, the war in Ethiopia, the Algerian question, and the relationship between colonialism and fascism.Footnote 58 It is difficult to ascertain precisely the reach or impact of these media, as much of their transmission was interrupted, curtailed and censored by metropolitan and colonial police. However, as the records of police and colonial offices in both Britain and France show, these materials were distributed at public meetings that were hundreds strong, were mailed across the world, and were published out of the same left presses as trade union and communist literature.Footnote 59

In order to present a message about the colonial situation and ongoing concerns by activists in those years, the LAI’s sections produced newspapers and pamphlets that were meant to be both informational and agitational, and attended to the timely issues of the day. Subscriptions to periodicals such as Contre l’Imperialisme were open to people around the world, and in the case of that newspaper, cost 18 francs for a twelve-month subscription from France or its colonies, and 25 francs from elsewhere. In these materials, authors highlighted the historical relationship between political control and economic exploitation, and highlighted protests and other events in the metropole and the colonies. In order to achieve a future after empire that addressed both concerns, participants laid out distinct histories of how the economic and political fates of their people became tethered to the logic of the contemporary world.

An early and striking example is the pamphlet likely produced by the Persian delegates to the 1927 congress.Footnote 60 The delegates who spoke on behalf of the Persian situation in Brussels were members of a Berlin-based dissident organization, likely founded in 1926, and made up mostly of students. Ahmed Assadoff and Mortaza Alawi were both known to German police in 1926, and in the next few years, would evade the Persian government’s calls for their deportation, more than once with the cooperation of the German authorities themselves. Footnote 61 The organization they founded was called the Revolutionary Republican Party of Persia, about which little information exists beyond its dissident activities in Berlin, including holding meetings of Persian students and publishing at least two pamphlets. (Their 1927 pamphlet is likely the document included in the League collection from the Brussels Congress.) The text began with an assessment of the place of Persia in the world economy and among the imperialist powers. The pamphlet described the situation in Persia as ‘imperial’, because of the economic and political domination of Britain in the region.

As dissidents of Persian origin living and working in Germany, the authors of this pamphlet found themselves well placed to critique both the government of Persia (in a place where the Shah’s laws could not reach them) as well as Anglo-American imperialism (a critique for which German authorities would not pursue them). Footnote 62 Assadoff and Alawi did not proceed from the assumption that rule by one’s own was necessarily more just; they discussed the difference between the form of governance under which Persians lived, ‘feudalism’ and the form that was the result of foreign influence, ‘imperialism’.Footnote 63 They explained how the two forms co-existed by explaining the relationship between capitalism and imperialism, in historical terms. ‘The history of the development of the capitalist economy, with all its anarchy, has its own laws’, the pamphlet began.Footnote 64 It was a tendency of this ‘modern economy’ to ‘liberate its narrow national confines and to conquer as vast as possible economic domains’, which resulted in their present political situation.Footnote 65 The authors noted too that ‘there is one law more powerful than all the economic conditions: economic laws are the mothers of all policies’.Footnote 66 They emphasized that their present political situation originated from the fact that European ‘imperialists’ had taken control of land, commodities, and trade in the country. The assessment of the situation in Persia that followed explained the political strife of the country’s poor under the Shah in terms of the gradual incorporation of the region into capitalism, and the resulting social relations and power imbalance. The historical specificity of the moment was clear; this was no general struggle between states, but the kind of arrangement that was only possible under modern capitalism.

Members continued to historicize this struggle throughout the LAI’s ten-year existence. In 1936, the French section published a pamphlet to mark the three hundredth anniversary of the French Antilles, ‘under the auspices of the French League Against Imperialism and Colonial Oppression’ in 1936. In this text, the tricentenary was described as ‘une fête impériale’.Footnote 67 The author was the Guadeloupean communist Stéphane Rosso, who began his case for this occasion’s absurdity with a history of the region. Beginning with ‘the Carib period’, Rosso explained the first encounter of Christopher Columbus with a ‘lush and fertile island’ that its inhabitants called ‘Kakukera’ and the Europeans named ‘Guadeloupe’. Rosso reminded readers that ‘contrary to what the official history reports, the indigenous people of “Kakukera” were not savages’.Footnote 68 Rosso described the Carib people and their pre-invasion society next. He emphasized their comfortable lodgings, knowledge of animal husbandry, agriculture, fishing, navigation, medicine, textiles, art, and sculpture. He noted that according to Columbus’s accounts, their society had no need of police, and that they lived in ‘complete liberty’.Footnote 69 The pamphlet went on to describe the establishment of slavery in the Antilles, its re-establishment, its eventual abolition, and the state of the government under the Third Republic. Such an account, with its empasis on the ‘non-savage’ and free lives of the original peoples of the islands despite the typical view (positioned against the account of slavery as imposed by European invaders) forcefully made the case for the unjustness of continued French control over territories overseas.

These types of analyses were meant to describe the present situation and relate it both to a long history of imperialism and the current relationship between economic exploitation and foreign rule. In order to try and spur the public on to participating in revolutionary activity, members of the LAI used various media to make legible a coherent and unified struggle against a common enemy. This was meant to translate into the disruption of the war machine and imperial economy, via specific forms of protest carried out where the LAI was most active.

Towards mass politics

The LAI was headquartered in Berlin from 1927 to 1933, when their offices were raided by the German police and staff were forced to flee the Nazi regime. In the years before the final raid, the LAI’s executive had overseen the distribution of materials and the support of various sections in Germany and around the world. They had also facilitated communication between the hundreds of organizations and individuals in the orbit of international dissident networks. Inside Britain and France, thriving sections of the LAI had brought together men and women from communist and socialist groups, trade unions, and anti-colonial organizations, and functioned as part of the multi-racial fabric of dissident activity situated in these broad imperial spheres.

The LAI also took up the form of an international organization in its interactions with other interwar international groups. For example, its leaders responded in writing to the twelfth session of the International Labour Conference, which met in Geneva in 1929. The conference produced a report on forced labour, the session’s main topic. This report detailed the forms of forced labour that persisted, the law and practice of forced labour, ‘opinions on the value and effects of forced labour’, and ‘the necessity for its regulation’.Footnote 70 In a memorandum addressed to the representatives of working-class organizations at this session, the LAI’s general secretaries Willi Münzenberg and Virendranath Chattopadhyaya, along with the British communist Emile Burns detailed the various forms of forced labour in the colonies to make the case that working conditions in the colonies were not only unjust (a point driven home by the comparison of these conditions to slavery in the nineteenth century and before) but also hurt working conditions for European workers.Footnote 71 This was an instance of one international organization addressing another, attentive to the in-betweenness of the particular audience of this memorandum – those ‘working-class organizations’ that attended to the International Labour Office (ILO)’s form of international politics. The three men used this memorandum to levy a critique that the narrow definition of ‘forced labour’ that came under the jurisdiction of the ILO’s conference ignored how coercion and force acted on workers the world over simply by virtue of their class position in Europe and that position coupled with the presence of colonial rule overseas.

The French section brought this mandate to bear on Paris, where workers from across the French empire encountered one another and built relationships based on their shared experiences.Footnote 72 For activists in the LAI and in other organizations like it, this gave them an opportunity to develop an argument against capitalism and imperialism specific to the forms of rule in each of the places where these workers came from. For example, when the Egyptian delegate at Brussels, Hafiz Ramadan Bey described his home country as ‘free and independent’ (presumably because it was not under direct colonial rule), Senghor refuted this characterization by referring to the position of his fellow activists in France: ‘As a representative of the Negro Defense Committee, I am bound to declare here that the Egyptian workers who support our committee are not of that opinion’.Footnote 73 Senghor argued that the ‘British paternalism in Egypt’ and the ‘occupation of the Suez Canal by Britain’ amounted to colonization, whether or not Egyptians were even nominally in high office – ‘what is colonization? To colonize is to rob a people of the right to manage its own affairs as best it can and as it sees fit’.Footnote 74 To Senghor and the Egyptian workers he cited, foreign control over a key waterway (and thus control over trade) was a fixture of enduring colonization.

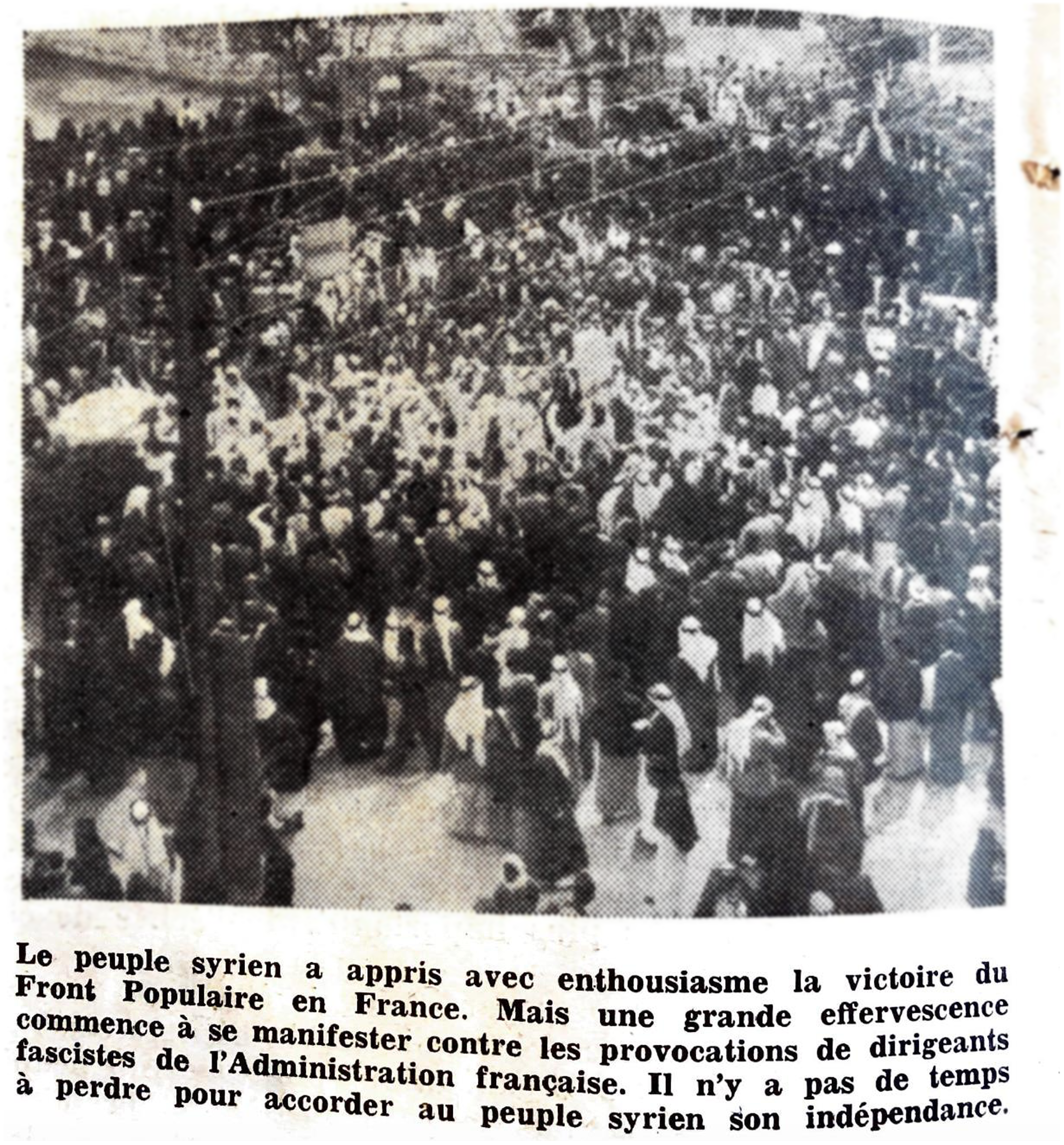

The LAI was eager to demonstrate the strength of working-class organization both in the metropole and the colonies. In the monthly journal Libération, published by the French section of the LAI, members published bulletins on the conditions in various French colonies. In an issue published June 1936, readers learned of the situation in Algeria, Morocco, Syria, Indochina, Martinique, and Palestine.Footnote 75 Photographs of public meetings and demonstrations punctuated these descriptions, conveying news of the conditions of oppression in these places but also of the desire of colonized people to gather, organize, and protest.

Figure 2. Photograph of open-air meeting in Palestine from Libération (June 1936).

For the Palestinian Arabs pictured here [Figure 2], Libération specified that the reason for their protest was the ‘systematic expropriation of land’.Footnote 76

Figure 3. Photograph of a crowd in Syria from Libération (June 1936).

This caption [Figure 3] suggests that the Syrian crowd’s support for the Popular Front and opposition to fascism should urge the reader to understand that the independence of the Syrian people should matter to those living in France.Footnote 77 The writers of this publication took care to show the presence of a mass movement in Palestine and Syria, as they did elsewhere, because it underscored the through-line of all the LAI’s public materials: colonial workers were ready to fight for their freedom.

The cover of the issue featured a quote attributed to Karl Marx translated into French: ‘A people which oppresses another cannot [itself] be free’.Footnote 78 Publications like Libération were meant to inform the French public but also to make the case for the imbrication of white French people in a shared struggle with those living under French rule overseas. The issue ended with a report on ‘slavery and forced labour in French colonies’, which detailed the various forms of indenture and coercion experienced by colonial workers. The attempt to draw together the radical trade union movement with the anti-colonial struggle in France was implicit in every instance of the enumeration of such conditions.

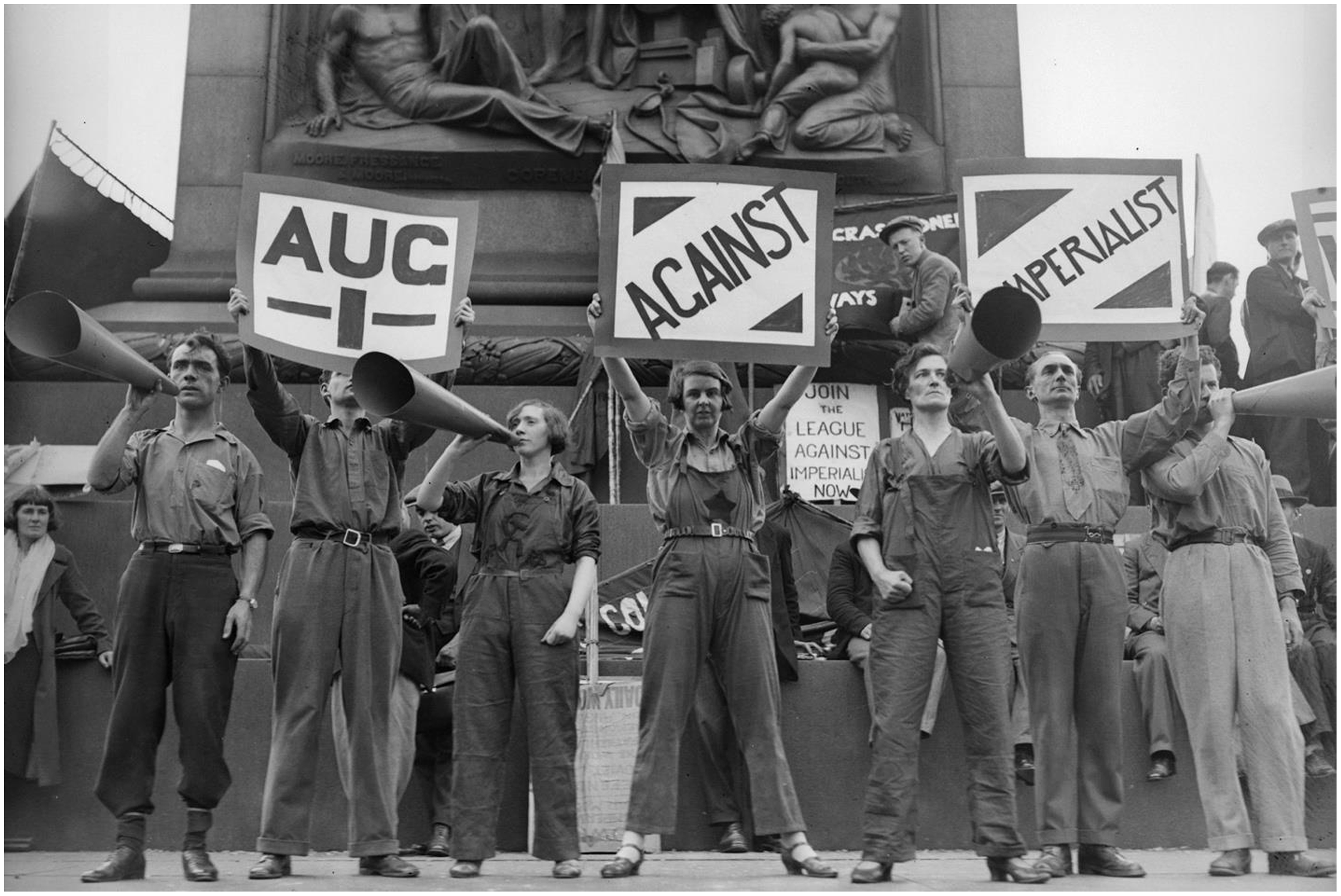

The LAI’s British section put on public displays to bring supporters to the anti-imperialist cause and demonstrate the relationship between working class struggle in Britain and struggles in British colonies. The working-class theatre group Red Megaphones participated in a LAI-organized demonstration at Trafalgar Square on August 1, probably in 1932. The actors were photographed [Figure 4] demonstrating at the base of Nelson’s column, with signs behind them that read ‘Join the League Against Imperialism Now’.Footnote 79

Figure 4. A demonstration at Trafalgar Square.

These demonstrations were not uncommon in these years and were organized by a variety of groups. What is significant about these gatherings was the conviction that the large public spectacle would serve to educate and agitate working people into an understanding of the specifically economic and political relationships they had with workers in the colonies, simply by virtue of their shared class position.

Working class theatre groups such as the Manchester-based Red Megaphones staged a play about the Meerut Conspiracy Trial several times in between 1931 and 1933, as did the Lewisham Red Players.Footnote 80 This was a form of ‘street theatre’, intended to be easily performed in front of a crowd, without a stage or crew. The short sketch was titled ‘Meerut’ and was written by the North-West London Hammer and Sickle Group. These actors were young: between fifteen and seventeen, four men and three women.Footnote 81 Men and women alike dressed in plain work-clothes suited to the aesthetic of the period’s ‘agit-prop’ performances. The play included the following exhortation to the audience – an audience we know was comprised of passersby in front of groups of workers off from their shifts, or by the government offices where people ‘lined up for the dole’.Footnote 82

The actors described the conditions experienced by Indian workers, and the repression they faced at the hands of British police and military. Harsh weather, poor wages, and ‘forced famine, forced starvation, forced disease’ were among the things the workers and peasants of India faced, and the actors used the details of these conditions to elicit not only feeling – but solidarity. Staging instructions from 1933 instructed actors: ‘feel the sketch, mean it, and you will convey the message in a way that will strike home to class-consciousness that is latent in even the most reactionary member of your worker audience’.Footnote 83 This message was detailed, vivid, and specific: ‘In Bengal mines are 35,000 women, working UNDERGROUND – forced to take their children with them from their hovels of sun-baked mud – to die at their sides as they work’.Footnote 84 They appealed to the crowds to use their organization as workers in Britain to disrupt the imperial machine, and they appealed to specific types of working people. The script reads:

-

FIFTH: Factory workers

-

SECOND: Housewives

-

FOURTH: Trade unionists

-

FIRST: By resolutions

-

THIRD: Demonstrations

-

FIRST: By strikes

-

ALL: FORCE THE RELEASE OF THE MEERUT PRISONERS (With hands through the bars) –COMRADES, HANDS ACROSS THE SEA! COMRADES, SOLIDARITY!Footnote 85

The reactions from these crowds were mixed, even hostile, and police often broke up the show. At one performance, police confiscated the broomsticks the actors used to represent the bars of the jail, ‘as being offensive weapons’.Footnote 86 The performance of ‘Meerut’ was dangerous to its actors, who faced confrontations with police, and was not always met with the response they hoped for. The aim, however, was the same as the aim of members of the French section when they distributed information on the origins of the French occupation of the Antilles, or conference delegates posing for a photograph. The attempt to reach a crowd in a British city [Figure 5] with messages of solidarity may appear to be worlds apart from the tableau [Figure 6] presented by the images of the Brussels Congress in 1927, but the performance of solidarity and the call to mass action embedded in both these gatherings was a constant throughout the LAI’s ten-year existence.

Figure 5. The Red Megaphones in Preston, Lancashire in 1932.Footnote 87

Figure 6. The Executive Council of the LAI at the Brussels Congress, 1927.Footnote 88

For the Red Megaphones, the specific injustice of the Meerut conspiracy trial was meant to agitate the crowd into joining a movement that would free dissidents half a world away. For the Brussels delegates, the singular event of their meeting was meant to coordinate myriad struggles the world over into a united effort that would emanate outwards as everyone returned home and began the work of spurring on their respective constituencies. Rather than an abstract vision of a world free from empire, however, those calls were underwritten by the collection of information, development of arguments, and demonstration of a universal problem through its specific effects on land, labour, and trade. It was the form of an international organization brought to life with the aspiration to mass action that facilitated this process and allowed the LAI to occupy a position in between the worlds of formal international politics and the politics of the streets.

After the interwar

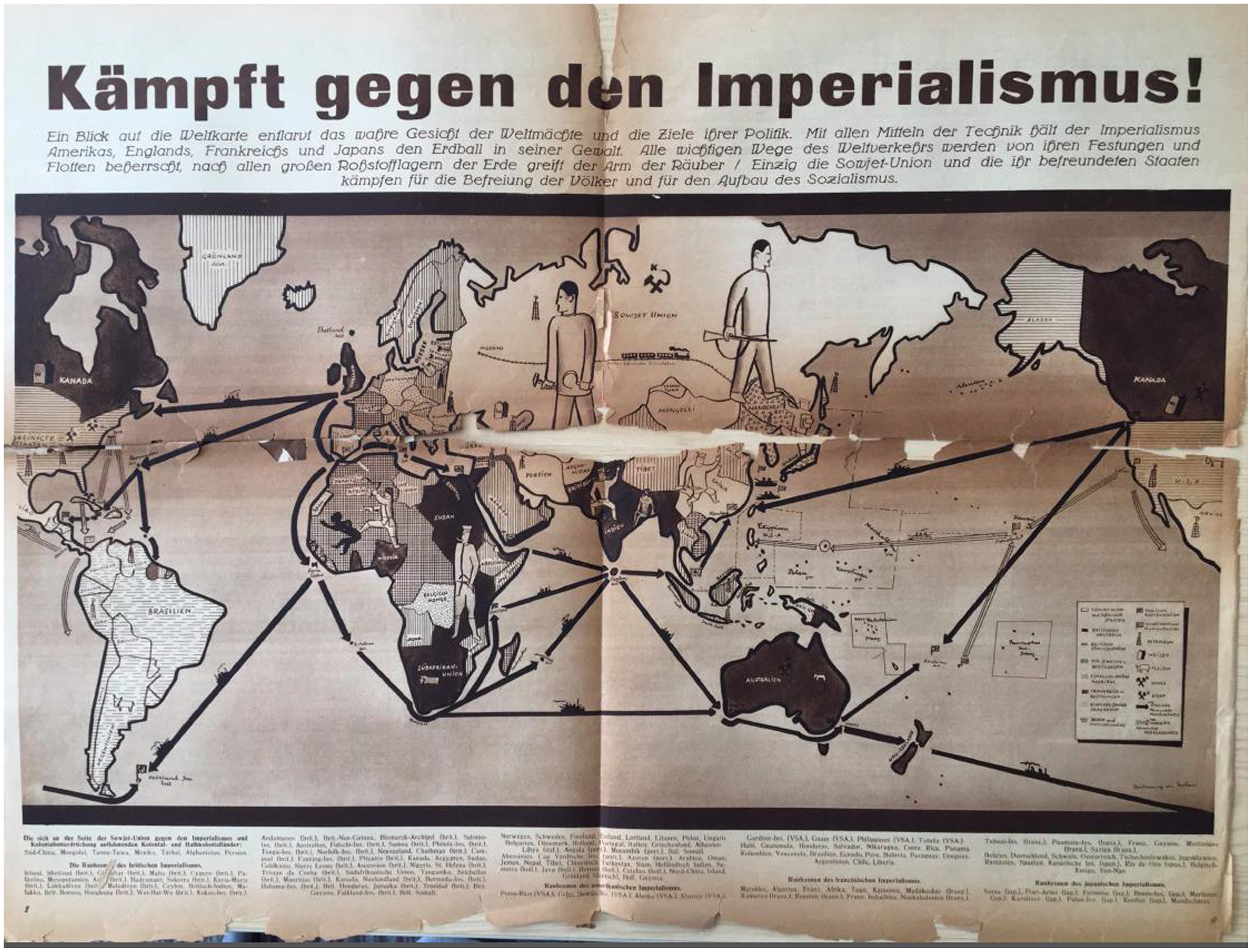

The LAI ultimately aimed to re-arrange the global political and economic relationships that allowed imperialism and capitalism to persist, like so:

Figure 7. A world map depicting the struggle against imperialism, Papers of Rajani Palme Dutt, People’s Museum, Manchester, UK.

When spatialized as in the map above [Figure 7], the flow of commodities and labour could be seen as crisscrossing territories governed by imperial powers, with the presence of police and troops overseeing it all.Footnote 89 In this map, one can see a specific vision of international order – depicting the world as cut up not by the political unit of the nation-state, but rather of the imperial bloc, and as divided by forms of economic activity.

If the first decades of the twentieth century had witnessed the near total spread of capitalism and imperialism, then the LAI’s participants argued that their struggle had to be global too. An emphasis on specificity inside of this single unit was built into the LAI’s mission; it was precisely the point that different parts of the world would need different approaches in order to bring about an anti-imperialist future, and it was in order to ascertain these conditions that delegates delivered reports to one another and drew links between their own experiences. As Adom Getachew has shown, ‘by the mid-1960s, statesmen and social scientists were wrestling with the limited economic gains of the first two decades of decolonization and began to question the ways in which the ideal of a universal process of development failed to correspond to the conditions of postcolonial states’.Footnote 90 She writes that for them, these conditions ‘cast the underdevelopment of the postcolonial world as the product of an imperial global economy’.Footnote 91 In the 1960s and 1970s, Third World leaders and economists would make the same case, before very different sorts of international organizations.

Perhaps there is not a direct causal link between these two moments. A new generation was at the helm of these governments, and the radical shift in the language and infrastructure of the international organization, coupled with the project of the developmentalist postcolonial state prove a barrier to a simple through-line. What emerges from the scattered archive of the LAI is a premonition of this postcolonial ‘underdevelopment’, woven into the exhortations to all workers in the heart of the empire to undermine this machine from the inside, precisely because it functioned as one economic unit. For global historians concerned with the relationship between political concepts and political practices (from ‘above’ and ‘below’), the LAI offers a site where these analytic categories were necessarily blurred from the outset. This blurring took place by necessity, because the very task of the LAI’s members was to join up particulars to form a universal. Through the framing of their current predicament as the result of a longer political and historical development, detailed descriptions of specific forms of land expropriation and labour exploitation, and the dissemination of this message through newspapers, pamphlets, and public performances, the LAI functioned as an international organization in between the spaces of formal, institutional politics and the agitational politics of mass struggle. Both aims, in the end, were largely aspirational, but as the material that survives from their brief association shows, members of the LAI embodied the material and utopian dimensions of this unstable global moment.

Disha Karnad Jani is a PhD Candidate in the Department of History and the Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in the Humanities (IHUM) at Princeton University.