Introduction

The Great Recession of 2007-2008, which followed on the bursting of the US housing bubble and the global financial crisis, caused dramatic changes in the economic circumstances of families. This has prompted vigorous debate on whether the recession led to a polarisation in deprivation and living standards or a ‘squeezed middle’ where the middle classes were worse affected (Whelan et al., Reference Whelan, Nolan and Maitre2017). In this paper, we extend this discussion by adopting a comparative perspective on the social stratification of changing patterns of deprivation dynamics.

Extending earlier discussions relating to social class, we focus on ‘social risk’ groups. These groups are likely to differ in their risk of negative outcomes due to non-social class, personal or family factors, including life-course stages. The comparative element of the paper recognizes that European countries were unevenly hit by the recession and that the negative consequences of the recession were cushioned/exacerbated by different national welfare regime arrangements.

Our analysis focuses on deprivation dynamics of ‘social risk’ groups across eleven European countries representing a range of welfare regimes between 2005 and 2014. Our descriptive analyses draw on the longitudinal component of the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) data and our dynamic perspective builds on the analysis of adjacent years for three critical periods.

Our paper focuses on three key research questions:

-

Is the pattern of ‘social risk’ group differentiation in persistent deprivation similar across countries and welfare regimes?

-

Is the ‘social risk gap’ – the absolute difference in deprivation across groups – larger in less generous welfare systems?

-

Did the recession lead to polarisation between the vulnerable social risk groups and the more advantaged groups?

The concept of social risk groups

The conceptual understanding of social risk was developed in contrast to social class as an important principle of differentiation. Following the Weberian tradition, social classes can be distinguished based on differing command over market resources (Goldthorpe, Reference Goldthorpe2007). As Goldthorpe (Reference Goldthorpe2007b: 13) observes, one of the primary objectives of the development of social class schemas is to bring out the constraints and opportunities typical of different class positions as they bear on ‘individuals’ security, stability and prospects’. As Goldthorpe and Jackson (Reference Goldthorpe, Jackson, Lareau and Conley2008: 528) stress, where economists’ notion of ‘permanent income’ can be measured only in a ‘one-shot’ fashion, social class may provide important information relating to longer-term command over resources.

Nevertheless, social class distinctions do not capture all the principles of differentiation that are relevant to a heightened risk. Life-course differences are an important element in distinguishing between groups, because of norms regarding the distribution of work across life stages and regarding the distribution of caring roles (Macmillan and Copher, Reference Macmillan and Copher2005). The development of the European welfare state has been linked to a political commitment to smoothing out the supply of resources across the life course (Dewilde, Reference Dewilde2003; Leisering and Liebfried, Reference Leisering and Liebfried1999). However, the life course perspective does not adequately encompass certain other dimensions of inequality to which the welfare state responds, such as lone parenthood, illness and disability, and barriers to labour market entry (Freeman and Rothgang, Reference Freeman, Rothgang, Castles, Liebfried, Lewis, Obinger and Pierson2010; Gibson-Davis, Reference Gibson-Davis, Brady and Burton2016; Priestley, Reference Priestley, Castles, Liebfried, Lewis, Obinger and Pierson2010; Kenworthy, Reference Kenworthy, Castles, Liebfried, Lewis, Obinger and Pierson2010). Life-course differences can be considered as a subset of a broader range of non-market social risks whose consequences are addressed by the welfare state. Social risk, in this sense, could be seen as associated with challenges arising from the increasing ‘commodification’ of welfare in the post-industrial economy, whereby needs are increasingly met through the market rather than through the family or as an entitlement from the state (Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby and Taylor-Gooby2004; Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990).

If social class captures differences in market power, ‘social risk’ captures barriers to accessing the market in the first place and the ability to convert such access into economic resources. Our focus on social risk can be located within the ongoing debate on the salience of social class in structuring social exclusion. Pintelon et al. (Reference Pintelon, Cantillon, Van Den Bosch and Whelan2013) note that the continued relevance of social class has been challenged by two partly competing perspectives. The individualization thesis (Beck, Reference Beck1992) draws attention to a range of factors including diversification of family structures which contribute to a diversification of routes into poverty resulting in a more heterogeneous poor population. The life-course perspective also challenges the traditional class perspective in focusing on social risks associated with a phase in the person’s life trajectory (Vandecasteele, Reference Vandecasteele2010). Taylor-Gooby (Reference Taylor-Gooby and Taylor-Gooby2004) connects new social risks with the life-course as the former are frequently associated with earlier stages of the life-cycle including entry to the labour force and care responsibilities at the stage of family formation. However, the perspective can incorporate a range of risks which are not adequately captured by hierarchical stratification structures such a social class.

Social risks are associated with both access to resources generated in the labour market and the ability to convert such resources into desirable outcomes. Looking at such risks implies a focus shift towards non-traditional social stratification factors as well as further consideration of the outcomes which we direct our attention to. Sen’s (Reference Sen2009) capability approach argues that in understanding poverty, people’s resources are only of instrumental importance in signalling what they enable a person to be or do; while what is of intrinsic importance is what a person can be or do. As Hick and Burchardt (Reference Hick, Burchardt and Burton2016:75) observe, this distinction is important as individuals differ in the resources required to achieve a specific level of functioning. Sen (Reference Sen1992: 26-38) labels these variations ‘conversion factors’. Thus, the ability to convert resources into the typical bundle of goods and services considered normative in a society may be qualified by a range of additional factors relating to needs and associated demands and restrictions (Alkire et al., Reference Alkire, Foster, Seth, Santos, Roche and Ballón2015; Ringen, Reference Ringen1988).

The primary concepts of the capability approach are functionings and capabilities. A ‘functioning’ is something a person succeeds in doing or being (Sen, Reference Sen2009: 75) while a person’s ‘capability’ refers to the ‘alternative combinations of functionings a person can achieve, and from which he or she can choose one collection’ (Sen, Reference Sen1992: 31). Thus, for Sen the relationship between resources is variable and deeply contingent. This has relevance for poverty analysis given the continued dominance of income-centric approaches to understanding poverty (Hick and Burchardt, Reference Hick, Burchardt and Burton2016: 77). While capabilities have priority over functionings in Sen’s framework, operational difficulties in capturing the former have led to arguments for focusing on the latter. Sen (Reference Sen1992: 112) has suggested that it may be possible to use information about a person’s functionings to draw inferences about their relatively basic capabilities – where we are confident that differences in outcomes are not a matter of choice. This is important for our later discussion of the relative advantages of income and deprivation indicators.

In what follows we discuss the impact of a range of factors that have implication for one’s ability to participate in the labour market and to convert resources into a variety of desirable outcomes relating to both current and persistent income poverty and deprivation. Here we distinguish non-market differentiation challenges to meeting one’s material needs that are linked to:

-

Life-course stage: children and people older than ‘working-age’;

-

Personal resources: illness or disability may limit a person’s capacity to work as well as involve additional costs associated with treatment, medication or disability-specific devices and aids;

-

Non-work caring responsibilities: responsibility for childcare or others who have an illness or disability is likely to reduce the time available for paid work;

-

Barriers to labour market entry that affect young adults who are seeking their first jobs.

Comparative welfare regime perspective

Individuals in Western economies meet their needs through markets, families and the state (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990). Markets are the main source of welfare for most working-age adults because their incomes come via labour and many of their welfare needs are met through purchasing goods and services. Families provide welfare through care services (mainly for children and adults with a disability), through pooling of incomes from the market and pooling of risks including the income shocks associated with illness or unemployment (Daly, Reference Daly2002; Western et al., Reference Western, Bloom, Sosnaued and Tach2012). Finally, states provide welfare by virtue of a redistributive social contract which has its roots in collective solidarity.Footnote 1

In identifying the regimes set out below, we combine the classic Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) threefold schema, subsequently extended with a fourth (Southern) regime by Ferrera (Reference Ferrera1996), with employment regime typologies (Gallie and Paugam, Reference Gallie, Paugam, Gallie and Paugam2000). Gallie and Paugam (Reference Gallie, Paugam, Gallie and Paugam2000) focus on the degree of benefit coverage and level of financial compensation for the unemployed and the scale of active employment policies. Focusing on European countries which are similar in terms of level of economic development, we distinguish the following regimes:Footnote 2

The social-democratic regime is characterised by its emphasis on universalism and redistribution. Employment flexibility is combined with generous social welfare and unemployment benefits to guarantee adequate economic resources independently of market or family. From this regime, we focus on Sweden, Finland and the Netherlands.

The corporatist regime places less emphasis on redistribution. Rights to benefits depend on being already inserted in the labour market with entitlements linked to lifelong employment. There is a greater emphasis on income protection and transfers and less emphasis on the provision of services. We include Austria, Belgium and France from this regime type.

The liberal regime emphasises provision through the market with the state acting only to support the market. Social benefits are typically targeted, using means tests, though there has been a recent shift towards negative income tax policies. These countries are characterised by flexible labour markets and low provision of services to promote and sustain employment. We include Ireland and the UK as representatives of this regime.

The southern regime is characterised by an emphasis on family as the provider of welfare with labour market policies relatively undeveloped and selective. The benefit system tends to be uneven and minimalist with no guaranteed minimum income. From this regime, we include Italy, Spain and Greece.

Transfers through the family across the life-course take place in all regimes but the form of the transfers can vary. In the social-democratic countries, financial transfers from older parents to adult children are more common than elsewhere. However, the amounts transferred tend to be the highest in Spain and Italy. The main form of support from older parents towards adult children in the southern regime is via prolonged co-residence (Attias-Donfut et al., Reference Attias-Donfut, Ogg and Wolff2005; Kohli and Albertini, Reference Kohli, Albertini and Saraceno2008; Albertini et al., Reference Albertini, Kohli and Vogel2007).

Conceptual and methodological aspects of income poverty and deprivation

Here we argue that our ability to proxy capabilities with functionings – following Sen –, will strengthen by moving our focus from point-in-time measures of disadvantages to the persistence of disadvantages. In addition, we argue that such ability can be further enhanced by focusing on material deprivation rather than income. A large body of research has criticized the use of income alone (Ringen, Reference Ringen1988; Nolan and Whelan, Reference Nolan and Whelan2011). Comparative European analysis has shown that the overlap between income poverty and deprivation measures is modest. The findings suggest that this is related to the extent to which current disposable income serves as an adequate proxy for longer-term resources. However, even when measured over time and adjusted for measurement error, income poverty and deprivation continue to capture distinct phenomenon, despite being substantially correlated (Kus et al., Reference Kus, Nolan and Whelan2016).

In brief, using indicators of material deprivation instead of income allows to better identify the poor and to capture what being poor means. In fact, deprivation indicators directly capture the multifaceted nature of poverty and social exclusion. While the specific focus of the paper is on persistent material deprivation, in the following we discuss income poverty dynamics because much of the existing literature has focused on poverty and, importantly, most of the following discussion can arguably be applied to deprivation.

Research based on panel data has established that poverty is an experience of varying duration (Bane and Ellwood, Reference Bane and Ellwood1986; Jenkins, Reference Jenkins1999; Fouarge and Layte, Reference Fouarge and Layte2005). The distinction between persistent and transient poverty is also important because the two have very different policy implications (Walker, Reference Walker1994). Whether many people experience poverty but quickly escape from it or poverty is a persistent and long-term phenomenon strongly matters. Persistent poverty has more serious consequences for a range of outcomes such as current and future labour market outcome, family behaviours/decisions, health, well-being and child development (Duncan and Brooks-Gunn, Reference Duncan and Brooks-Gunn1999; Power et al., Reference Power, Manor and Matthews1999). In this paper, we follow Polin and Raitano (Reference Polin and Raitano2014), and Ayllón and Gábos (Reference Ayllón and Gábos2017) who define persistence as being income poor or deprived in the current year and in the previous year.

Existing research

Several recent studies have focused on material deprivation (Guio et al., Reference Guio, Marlier, Pomati, Atkinson, Guio and Marlier2017; Ayllón and Gábos, Reference Ayllón and Gábos2017). Guio and Marlier (Reference Guio, Marlier, Atkinson, Guio and Marlier2017) employed EU-SILC data to analyse the evolution of material deprivation over time across the EU. They found that the increase in the level of material deprivation characterizing the countries most affected by the recession was the result of both an increase in entry rates into material deprivation and a decrease in exit rates. In an extension of this work Guio et al. (Reference Guio, Marlier, Pomati, Atkinson, Guio and Marlier2017) examined which material deprivation items people do without as their income decrease. There is a high level of similarity across countries in the items that are curtailed. Across the six items available in the longitudinal EU-SILC data for 2011, the first item to be curtailed was an annual holiday, followed by the capacity to meet unexpected expenses, a protein meal, keeping the home adequately warm, avoiding arrears, and having a car or van. Based on the 13 items available in the cross-sectional EU-SILC data for 2009, the order of curtailment was the following: inability to afford holiday, unexpected expenses, replacing worn-out furniture, pocket money, leisure activity, drink/meal out with friends, new clothes, protein meal, keeping home warm, avoiding arrears, a car/van, computer/internet, new shoes.

Research on eight countries using EU-SILC data has found a high level of persistence of income poverty and a somewhat lower level of persistence of severe material deprivation between waves (Ayllón and Gábos, Reference Ayllón and Gábos2017) with a very strong persistence of low work intensity.Footnote 3 All three indicators showed evidence of genuine state dependence between waves, namely being in the state in one wave was causally related to being in the state in a subsequent wave even when individuals’ observed and unobserved characteristics were taken into account.

Data and methods

In this study, we draw on the longitudinal component of the EU-SILC data over the period 2005 to 2014 that allows us to examine the impact of the boom, recession and early recovery on trends in deprivation for the different social risk groups.Footnote 4 More precisely, we focus on pairs of years in three periods and examine transitions between waves: pre-recession (2005-2006), early recession (2008-2009) and early recovery (2013-2014). The EU-SILC is an annual survey that collects information on households and individuals across a wide range of social and economic domains from individual income and household income to labour market status, health, education, housing. The survey was launched in 2003 and the data is output-harmonised to allow European comparisons. The EU-SILC is used to monitor poverty, social inclusion and living conditions across EU-member states within the Europe 2020 strategy.Footnote 5

The EU-SILC longitudinal component follows a 4-years rotational design, where every year 25% of the sample exits the survey and a new random sample of household enters the survey.Footnote 6 Although EU-SILC follows individuals for up to four waves, the number of cases available for analysis declines very rapidly as the period of observation extends because of the high rate of ‘field’ attrition – which is particularly high in countries such as the UK and Ireland (Grotti et al., Reference Grotti, Maître, Watson and Whelan2017; Jenkins and Van Kerm, Reference Jenkins, Van Kerm, Atkinson, Guio and Marlier2017). For this reason, we follow Krell, Frick and Grabka (Reference Krell, Frick and Grabka2017) and focus on transitions between pairs of waves rather than following people across longer periods of time. This also minimizes the potential for non-random attrition to influence the results (Ayllón, Reference Ayllón2008; Cappellari and Jenkins, Reference Cappellari and Jenkins2004; Jenkins and Van Kerm, Reference Jenkins, Van Kerm, Atkinson, Guio and Marlier2017). Given the limitation of the data available to us, our focus is inevitably on short-term effects. However, we recognise the need for further exploration of longer-term consequences (Brandt and Hank, Reference Brandt and Hank2013). This is likely to be particularly crucial in the case of children; hopefully such effects can ultimately be explored, making use of longitudinal cohort data.

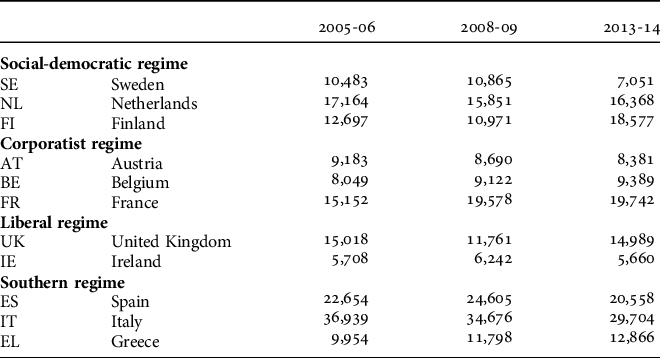

We focus on eleven countries selected to reflect welfare regimes variation – see Table 1 (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Eurofound, 2007; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Maître and Kingston2014). Our sample includes all individuals of any age who are observed for two consecutive waves, namely in both 2005 and 2006; or 2008 and 2009; or 2013 and 2014. The final samples size are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Number of cases available by country and pair of years.

Source: EU-SILC data.

All the results in the paper are based on descriptive analyses and we use statistical modelling to test for the significance of the differences in material deprivation between social risk groups. All the analyses adjust the standard errors for weighting of the data and clustering of the observations at household level. We employ longitudinal weights to ensure that the longitudinal sample is representative of the national population.

Measuring deprivation

We use the official measure of material deprivation as endorsed in 2009 by the EU (European Commission, 2015). Material deprivation is measured at the household level with the score attributed to all household members. It involves living in a household that is unable to afford 3 or more out of the following 9 basic goods and services:

-

1. To pay on time mortgage, rent, utility bills, hire purchase or other loan payments;

-

2. One week’s annual holiday away from home;

-

3. A meal with meat, chicken, fish (or vegetarian equivalent) every second day;

-

4. To meet unexpected financial expenses (set amount corresponding to the monthly national at-risk-of-poverty threshold of the previous year);

-

5. A telephone (including mobile phone);

-

6. A colour TV;

-

7. A washing machine;

-

8. A car;

-

9. To keep its home adequately warm.

The content of the items and the focus on affordability together with our subsequent focus on persistent deprivation is consistent with our desire to capture genuinely enforced deprivation and thus to provide, in Sen’s terms, as solid a basis as possible for inferences from functionings to capabilities.

Although a newer indicator of deprivation is being introduced, which includes a wider range of items (see Guio and Marlier, Reference Guio, Marlier, Atkinson, Guio and Marlier2017), we focus on the nine-item indicator here since it is available for the three periods we examine. Although examining the nine material deprivation indicators one at a time might provide some additional insights, we are reluctant to do this because the material deprivation index has been constructed and tested for validity and reliability as a composite measure. An examination of the number of items lacked has shown that the recession not only has pushed more households into material deprivation, but has also intensified its impact (Guio et al., Reference Guio, Marlier, Pomati, Atkinson, Guio and Marlier2017).

Results

The context

The period from 2005 to 2014 is one of dramatic economic change, encompassing a period of economic growth, the Great Recession, and early recovery. Accordingly, in this paper we focus on three pairs of years: 2005-2006, a period where unemployment rates were generally stable or falling; 2008-09, the period with the sharpest rise in unemployment in most of the countries; and 2013-14, the early recovery period in the countries characterized by the biggest rise in unemployment with the recession.

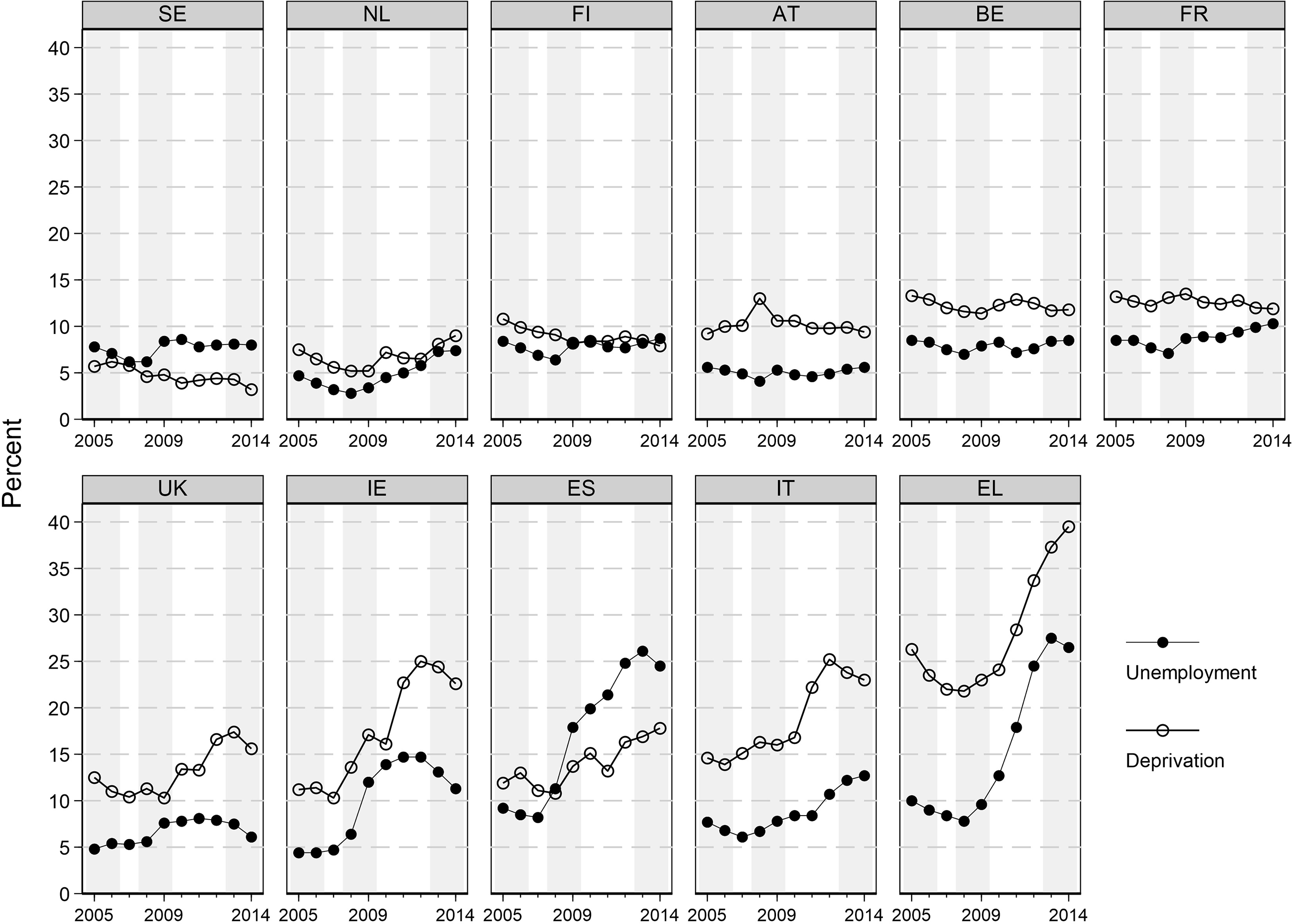

Figure 1 shows the unemployment rate and the deprivation rate from 2005 to 2014 across the eleven countries we examine in this study. In this figure, as well as in those which follow, countries are ordered according to the welfare regimes they belong to: from the left to right (here also from the top to the bottom) we have the social-democratic regime (SE, NL and FI); the corporatist regime (AT, BE and FR); the liberal regime (UK and IE); and the southern regime (ES, IT and EL).

Figure 1. Trends in unemployment rate and material deprivation rate, 2005-2014

Source: Eurostat LFS statistics (unemployment) and EU-SILC (deprivation).

Note: unemployment rate for persons aged 15-74. The vertical grey bands indicate the periods we focus on.

As Figure 1 shows, the sharpest increase in unemployment was between 2008 and 2009 for most countries, but with substantially greater increases in Greece, Spain, Italy and Ireland before the turning point in 2012 and 2013. There is no sign of a fall in unemployment in Italy by 2014, however. Ireland had a very low unemployment rate in 2005 at just over 4%. It rose very sharply in the recession, reaching almost 15% in 2012 before dropping back to just over 11% by 2014. Spain and Greece began with a higher-than-average unemployment rate (over 8% for Spain and Greece in 2005). In both countries, it rose very sharply during the recession, reaching over 26% by 2013. Italy’s unemployment rate was lower than this initially, at about the average across the remaining seven countries; but it rose to a higher level during the recession remaining high at over 12% in 2014. In the remaining seven countries, the rate averaged about 7% in 2005, falling to under 6% by 2008 before rising in the recession to reach about 8% in 2014.

Concerning material deprivation, Figure 1 shows a wide variation between countries and over time. Overall, we see that in the social-democratic and the corporatist regimes, material deprivation never exceeds 15%. Material deprivation is significantly higher in the other regimes, and it reaches the peak of 40% in Greece in 2014. This country particularly stands out: its lowest value in 2008 (22%) was higher than the highest reached in all other countries apart from Ireland and Italy mid-recession.

The lowest values were found in the three social-democratic countries, which averaged between 6 and 8%. The impact of the recession is very clear for Greece, Ireland and for Italy. Material deprivation was less responsive to the recession in other countries.

The dynamics of material deprivation

As shown in the previous section, European countries vary significantly in the levels and trends of both unemployment and material deprivation rates. On the one hand, we have found social-democratic countries experience the lowest rates in both outcomes, while on the other hand southern countries and Ireland experience the highest levels of unemployment and deprivation, and the highest increases with the recession.

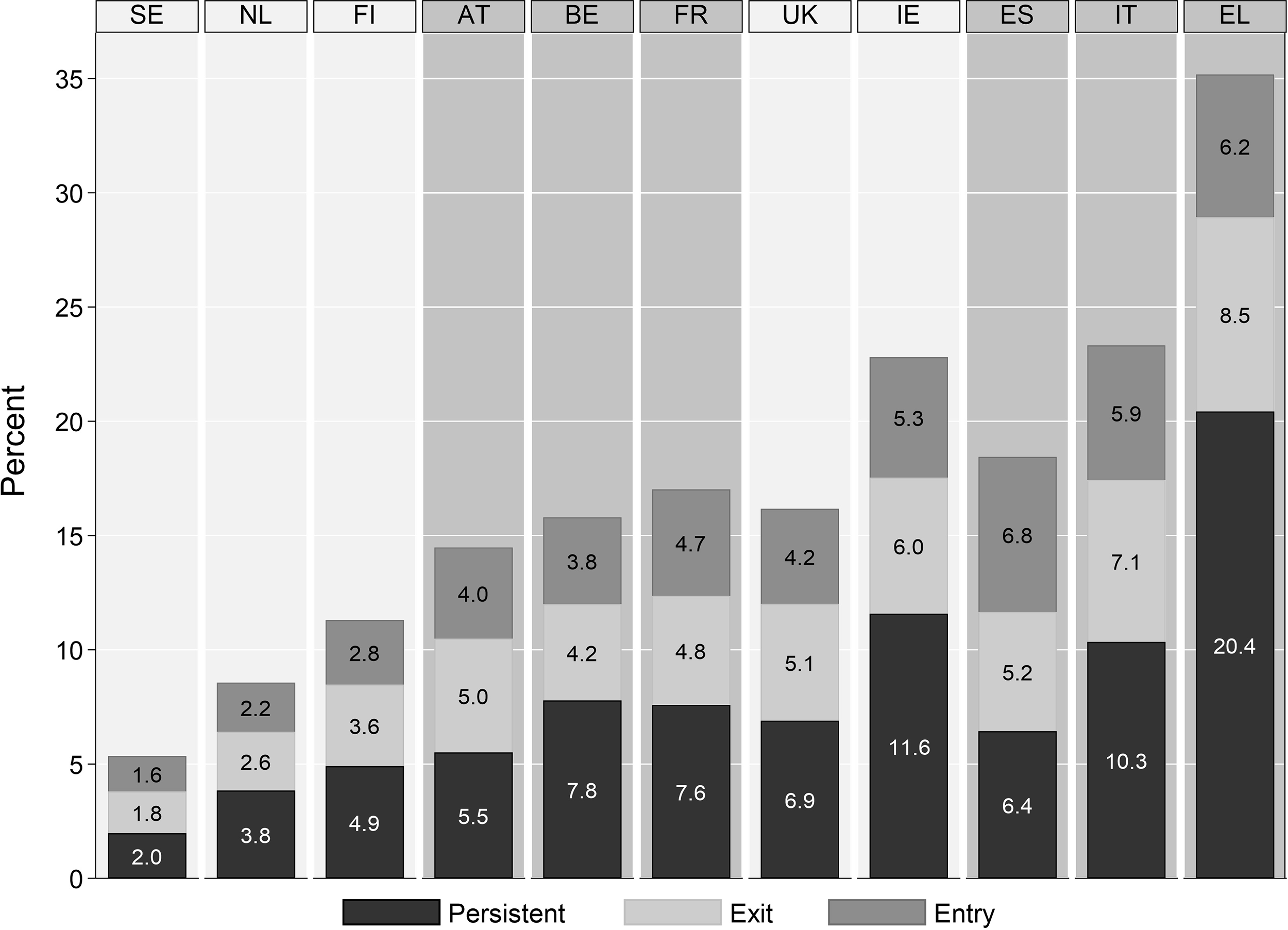

Figure 2 reports deprivation dynamics for the 11 countries examined.Footnote 7 As noted earlier, we focus on the transitions between 2005 and 2006; 2008 and 2009; and 2013 and 2014. In Figure 2, we pool the three periods and distinguish between those persistently deprived, those entering deprivation and those exiting deprivation.

Figure 2. Deprivation dynamics by country, % (average across periods)

Source: EU-SILC data, for 2005-06, 2008-09 and 2013-14.

The overall levels of deprivation – captured by the total height of the bars – mirror the unemployment levels presented in Figure 1, in terms of country ranking. Country differences are striking also in this case. Comparing Sweden with Greece, the two countries at the extremes, overall deprivation in the latter is 7 times higher than in the former (35 vs 5%), while persistent deprivation is more than 10 times higher (20 vs 2%).

Focusing on individuals in households that have experienced some deprivation, Figure 2 shows that individuals are more likely to be persistently deprived rather than to be entering or exiting deprivation. Persistent deprivation, indeed, represents the most widespread situation in all countries but Spain. Between 35% and 58% of overall dynamics are represented by persistent deprivation. Greece and Ireland represent the worst-case scenarios in terms of deprivation persistence and its contribution to overall deprivation.

The results presented so far are in line with the expectations relating to lower levels of both overall and persistent deprivation for the countries associated with the most generous welfare regimes. However, differences between the UK and Ireland are greater than might have been expected with the former more closely resembling the corporatist countries.

Persistent deprivation of social risk groups

In this section, we focus on variation in the most severe deprivation dynamic, i.e. persistent deprivation, across social risk groups. As discussed above, we identify social risk groups based on the challenges individuals face to meet their material needs, including lone parenthood, disability, age-dependency (children, those transitioning to adulthood and people of retirement age). The groups we identify are:

-

Lone parents (all ages) and their children;

-

Working-age adults aged 18-65 with a disability and their children (excluding lone parents);

-

Other children under age 18 (children of two-parent families);

-

Other young adults aged 18-29 (not a lone parent and not having a disability);

-

Other working-age adults aged 30-65 (not a lone parent and not having a disability);

-

Other older adults aged over 65.

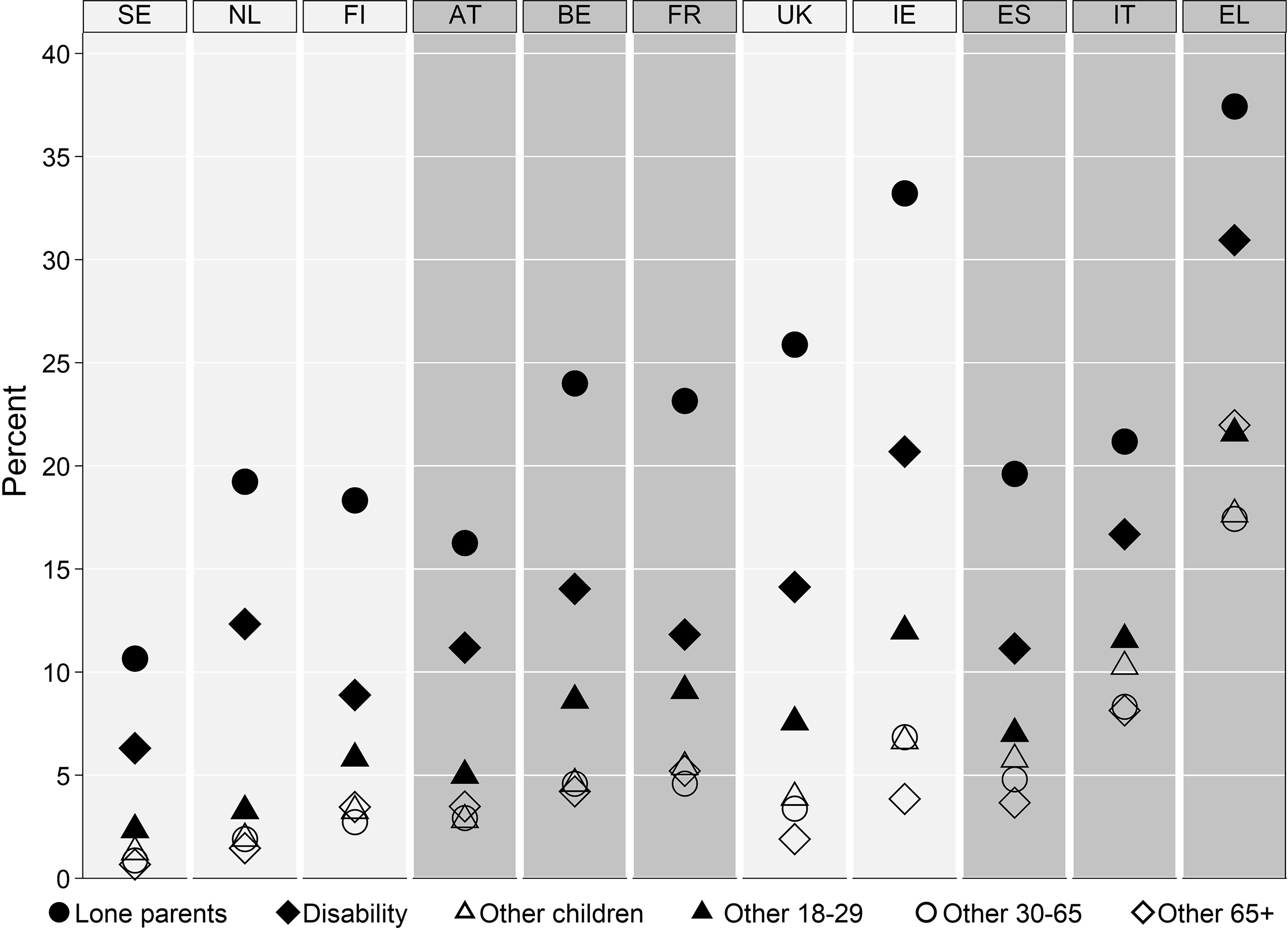

Figure 3 shows persistent deprivation rates by country and social risk group. As the figure shows, there is a wide heterogeneity in the risk of being persistently deprived across groups and this is true for all countries. Moreover, the pattern of stratification in deprivation risks is strikingly stable across countries. On the one hand, working age adults (in Figure 3 labelled ‘Other 30-65’), other children, and other adults over 65 (‘Other 65+’) are the groups which experience the lowest risk of being persistently deprived, and experience very similar rates within countries – differences between these groups do not exceed 5 percentage points; on the other hand, people with a disability and especially lone parents are the most disadvantaged groups. This is true for all countries.

Figure 3. Persistent deprivation of social risk groups by country

Source: EU-SILC data, for 2005-06, 2008-09 and 2013-14.

Persistent deprivation rates for working age adults aged 30-65, which represents the largest group in size (see Figure A1 in the Appendix) but the least disadvantaged group in most countries, range between 1% in Sweden and 8% in Italy, with Greece being an outlier in this case with a rate of 17%. At the other extreme, persistent deprivation for lone parents, who represent the smallest group but the most deprived, ranges between 11% in Sweden and 37% in Greece. In all countries, this group is followed by people with a disability and then by young adults (‘Other 18-29’). In Greece, older adults have a similarly high deprivation rate to the young adults. In the UK, Ireland and Spain, older adults 65+ are the least likely to be persistently deprived.

Therefore, to answer our first question we can say that the way in which risks are stratified between groups is remarkably similar across countries. Notwithstanding this, great variation across countries is visible in levels and in the gap in persistent deprivation between the most and the least disadvantaged groups.

Social risk gap

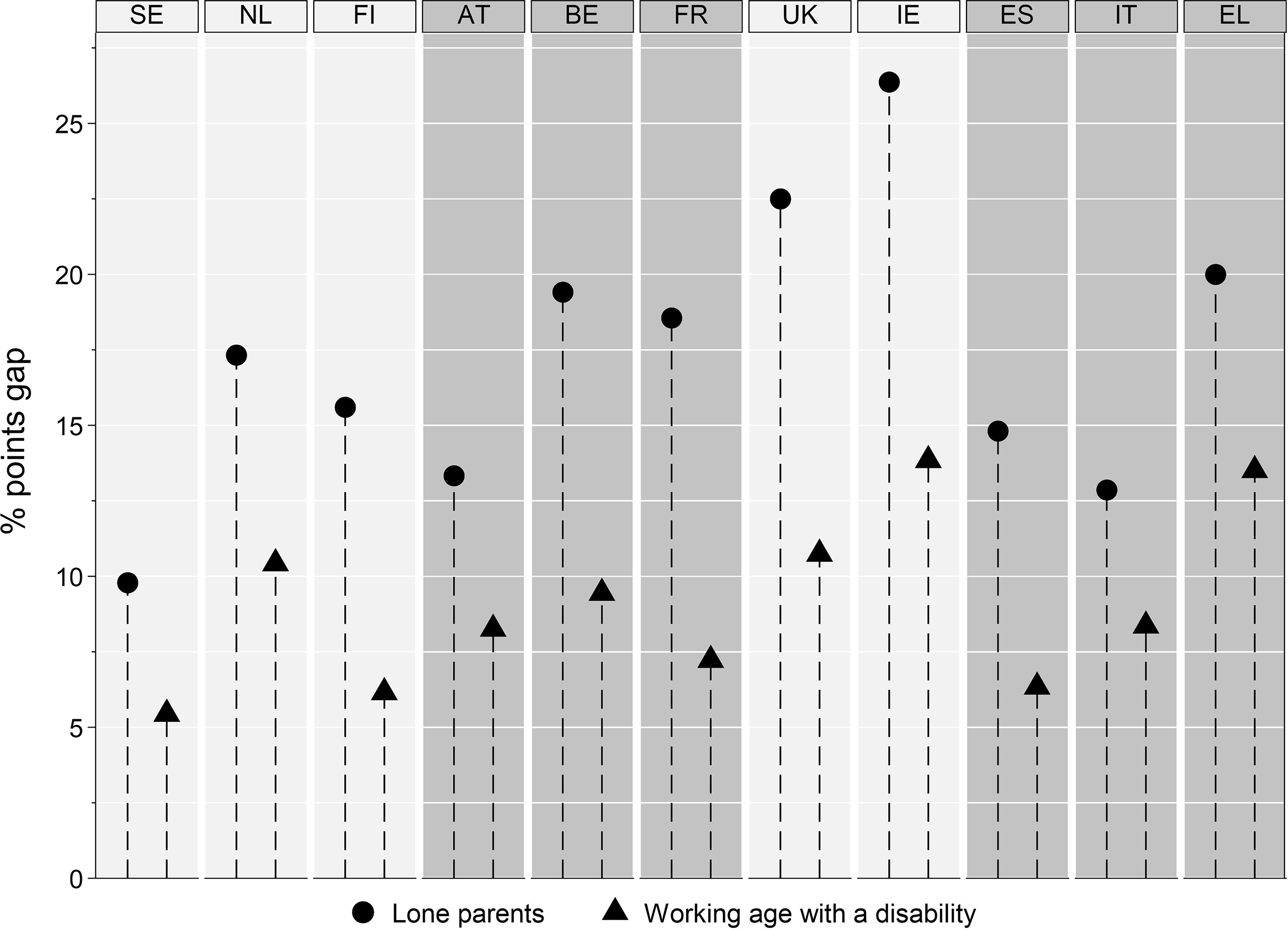

Here, we focus on the two groups that are distinctive in their experience of persistent deprivation, namely lone parents and people with a disability. In Figure 4 we present what we term the ‘social risk gap’ which represents the absolute gap in persistent deprivation for the two most disadvantaged groups and the reference group represented by working-age adults – the largest and generally least disadvantaged group.

Figure 4. Social risk gap. Persistent deprivation gap for lone parents and people with a disability compared with working age adults, by country

Source: EU-SILC data, for 2005-06, 2008-09 and 2013-14.

The gap for lone parents is represented in Figure 4 by a dot while the gap for people with a disability is represented by a triangle. The patterns that we observe across countries do not conform closely to our expectations: a smaller gap in countries characterized by a generous welfare state. Looking at lone parents, while, on the one hand, they present the largest risk gap in Ireland (almost 27 percentage points) and the United Kingdom (22.5 percentage points), on the other hand we do not observe the smallest gap in the social-democratic countries.Footnote 8 While Sweden is certainly the country that provides the best protection for this group with a gap of 10 percentage points, Italy and Spain perform better than Finland and the Netherlands. Corporatist countries lie between the liberal and the southern countries.

Concerning people with a disability, we observe a considerably smaller gap compared with lone parents, and certainly much more similar gaps across countries. Indeed, while the gap for lone parents has a range of 17 percentage points (comparing the two extremes Sweden and Ireland), the gap for people with a disability has a range of 8 percentage points (comparing the extremes Sweden and Ireland again). No clear pattern is observed across welfare regimes. Although Greece certainly emerged as the country where persistent deprivation was more widespread (with an overall rate of 20.4%), it does not represent the most unequal country in the way deprivation risks are distributed across groups.

Overall, our hypothesis that the social risk gap was larger in less generous welfare systems is not fully supported. Indeed, vulnerable groups do not seem to be more protected in more generous welfare regimes.

Social risks and the recession

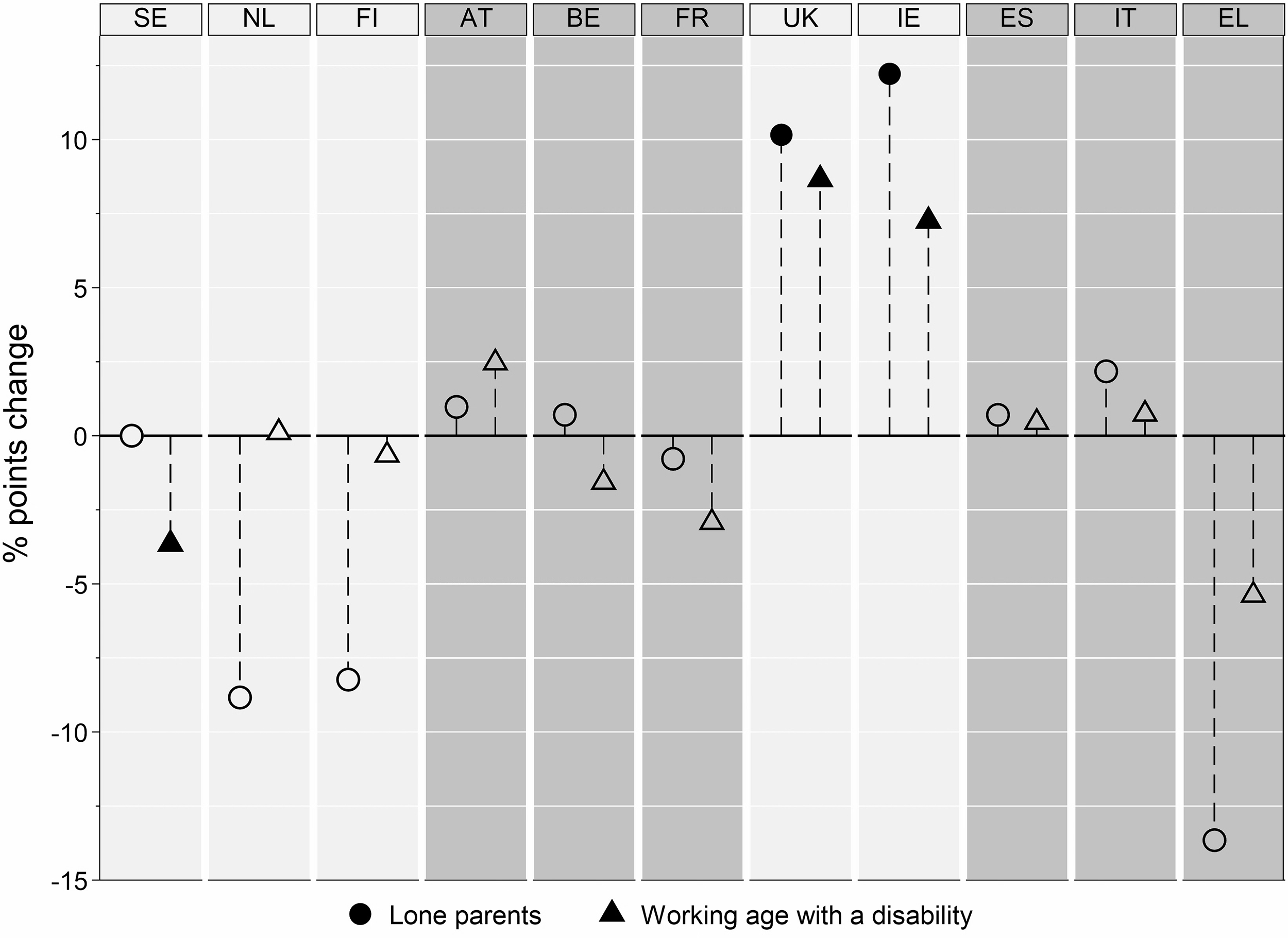

As a final step, we investigate the extent to which the recession led to polarisation or convergence between the vulnerable social risk groups and the more advantaged groups. Figure 5 reports changes between 2005-06 and 2013-14 in the social risk gap. A positive change indicates that the gap between the vulnerable and advantaged groups has increased over time, signalling polarisation. A negative change indicates convergence. Solid symbols indicate that the changes in the social risk gap are statistically significant at the conventional 95% level.

Figure 5. Changes between 2005-06 and 2013-14 in the social risk gap. (Solid symbols indicate statistically significant changes at 95%)

Source: EU-SILC data, for 2005-06 and 2013-14.

For most of the countries, the absolute gap for lone parents and people with a disability compared to the reference group has not registered a statistically significant change over time, as indicated by the empty symbols in the Figure 5. In many cases (e.g. Greece) a seemingly large change did not reach statistical significance possibly because of the small size of the group in question (see Appendix Figure A1).

The only significant changes were for the two liberal countries and Sweden. The United Kingdom and Ireland experienced an increase of more than 10 percentage points in the social risk gap for lone parents and an increase of between 7 and 9 percentage points for working age people with a disability. This indicates a polarisation of the social risk gap in persistent deprivation for both lone parents and people with a disability in the two liberal countries. The only sign of statistically significant convergence is registered in Sweden for working age people with a disability, who experience a decrease in the social risk gap of about 4 percentage points.

Conclusions

Atkinson and Morelli (Reference Atkinson and Morelli2011: 49) in an analysis of the relationship between economic crisis and inequality conclude that there is no hard and fast pattern and crises differ greatly from each other in their causes and outcomes. Focusing specifically on the recent Great Recession, Jenkins et al. (Reference Jenkins, Brandolini, Micklewright and Nolan2013) showed that the initial distributional effects varied widely across countries, reflecting differences not only in the macroeconomic downturn but also in the cushioning effects of cash transfers and direct taxes. Thus, it is far from clear whether the literature relating to long-term trends in inequality enables us to understand the impact of the recent economic crisis and the way it has varied across countries.

Whelan and colleagues (2017), focusing on trends in income, material deprivation and economic stress provided evidence of the extent to which the impact of the Great Recession varied even among the hardest hit countries, and even more so between them and the less affected countries. Several studies have shown the advantage of going beyond income and incorporating direct measures of material deprivation to understand the socio-economic distribution of the impact of economic shocks. In this paper, we have sought to extend this approach by focusing on a comparative analysis of the deprivation dynamics for social risk groups. In adopting this approach, we sought to address some of the problems involved in operationalising Sen’s distinction between functionings and capabilities by providing a stronger basis for inferences relating to the latter based on the observation of the former. Countries included in the study cover different welfare regimes and the time span covered goes from the pre- to the post-recession period.

It is worth noting that the countries included in the analysis had very different experiences with the recession over the period. Focusing on the unemployment rate as a key indicator of the capacity of individuals and families to meet their needs through the market, three countries stand out: Spain, Greece and Ireland. Countries’ different experiences are reflected in the changes over time in material deprivation, with very sharp increases in Greece; sharp increases in Ireland; and a substantial, though less dramatic, increase in Spain, perhaps moderated by familial supports in this country. Italy also experienced a sizeable increase in material deprivation, similarly to Ireland from 2010 onwards. Most of the increase in deprivation happened during the course of the recession rather than at the very start in 2008-09. This is consistent with households maintaining their standard of living by drawing on accumulated resources in the early recession but curtailing consumption later as resources are eroded.

Our results show that two groups stood out as having substantially higher levels of (persistent) material deprivation: lone parent families and families affected by working age disability. Both groups had a markedly higher deprivation rate than the reference group of other adults aged 30-65. In line with our expectations, the ranking of social risk groups in terms of deprivation rates was roughly the same in all countries, although with varying levels of deprivation. Contrary to our expectations, instead, the deprivation gap between both lone parents and working-age adults with a disability and the less vulnerable groups was uniform across countries. In fact, the social risk gap was not appreciably smaller in the most generous countries of the social-democratic regime, but the gap tended to be noticeably larger in the two liberal countries characterized by less generous welfare provision, the UK and Ireland. It is striking that the same two groups emerged as experiencing higher deprivation rates across very different types of welfare system. This suggests that none of the systems is particularly successful at addressing the particular barriers faced by these groups, and that the liberal system is distinctively worse in this respect.

Finally, we investigated the impact of the recession across social risk groups. Our results suggest that there was no overall evidence of polarisation in material deprivation in the sense of an increase in the gap between the two vulnerable groups and the reference group. There were differences in this respect between countries, however. Again, the most distinctive pattern was found for the two liberal countries, the UK and Ireland. These countries, with their means-tested, targeted approach that emphasises cash transfers performed poorly in protecting the living standards of vulnerable groups during the recession as reflected in a polarisation in persistent deprivation.

The limited evidence for ‘hard and fast patterns’ relating to the nature of the relationship between economic crisis and persistent inequality means that a fuller explanation of trends in polarisation clearly requires a more detailed focus on micro-factors or country-specific welfare provision. However, data limitations relating to the quality of the panel data in the EU-SILC are likely to set severe constraints on the extent to which such a comparative agenda can be successfully pursued employing that source.

Our use of the welfare regime approach was intended to bring out similarities and differences in the short-term effects of the Great Recession. Clearly such approaches ultimately need to be complemented by in depth historical analysis of specific contexts and strategic responses of individual countries as in Eichengreen’s (Reference Eichengreen2015) treatment of Iceland, Ireland and Greece. Furthermore, while the data available to us mean that our focus was necessarily on short-term effects, inevitably the impact of the Great Recession will involve much longer-term effects. This is likely to be particularly true in relation to its consequences for children and hopefully the increasing availability of longitudinal cohort studies will allow these issues to be addressed. Ultimately addressing the issues of winners and losers will require longitudinal and comparative analysis at both macro and micro levels.

To conclude, we should note that the emphasis, on whether there was a polarisation or convergence of social risk, might lead to missing some important nuances. Polarisation can hide a good news story if the circumstances of all families improve but the polarisation is due to a faster improvement for the initially advantaged group. Convergence can hide a worrying story if it is driven by a deterioration in the circumstances of the initially advantaged group with no real improvement for the vulnerable group.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279421000210