Fruit and vegetable consumption is a key part of a healthy balanced diet, as they contain essential vitamins, minerals and dietary fibre(1). The WHO recommends that children from the age of 2 years consume at least five portions of fruit and vegetables daily(2). In 2018, only 18 % of children aged 5–15 years in England ate five portions of fruit and vegetables daily(3). It was reported that the average number of portions that children were eating was three portions per d(3). Alarmingly, in Northern Ireland, consumption of five portions of fruit and vegetables is below the recommendation in all age groups(4).

High fruit and vegetable intake is associated with physical health benefits such as reduced risk of cancer and CVD(Reference Aune, Giovannucci and Boffetta5,Reference Wang, Li and Bhupathiraju6) and low fruit and vegetable intake has been associated with a higher risk of obesity in school-aged children(Reference Mekonnen, Tariku and Abebe7). Fruit and vegetable intake has also been shown to be associated with greater respiratory health and children who consumed a higher intake of fruit at the age of 8 years had a lower risk of asthma which lasted up to the age of 24 years(Reference Sdona, Ekström and Andersson8). Fruit and vegetable intake is therefore essential for physical health. For every additional portion of fruit and vegetable intake, it has been found that the risk of mortality from CVD, cancer and respiratory disease decreases up to a threshold of about five portions of fruit and vegetables per d(Reference Wang, Li and Bhupathiraju6). Fruit and vegetable intake has also been linked to mental health benefits. A systematic review of fruit and vegetable intake and mental health found an association between fruit and vegetable intake and better mental health in children aged 4–13 years(Reference Guzek, Głąbska and Groele9). However, it is unknown whether fruit and vegetable consumption on its own has physical and mental health benefits or whether these individuals have a healthier lifestyle in general. There is also the possibility that poor mental health may impact engagement in healthier dietary intake.

Improving the diet of children is particularly important as poor diet in childhood has been associated with adult health problems such as obesity(Reference Rampelli, Guenther and Turroni10), CVD(Reference Kaikkonen, Mikkilä and Magnussen11) and diabetes(Reference Jääskeläinen, Magnussen and Pahkala12). There is evidence that dietary habits acquired in childhood carry on into adulthood(Reference Movassagh, Baxter-Jones and Kontulainen13) and that adults prefer to eat foods that they ate as children(Reference Wadhera, Capaldi Phillips and Wilkie14). Therefore, early intervention in children’s diet will result in health benefits not only in childhood but also when they reach adulthood.

Previous research has shown that parents’ dietary habits, availability, accessibility and preferences are correlated with fruit and vegetable intake in children(Reference Bere and Klepp15,Reference Wolnicka, Taraszewska and Jaczewska-Schuetz16) . However, Bere and Klepp (2005) also found that past intake was the strongest predictor of future fruit and vegetable intake which supports the importance of targeting healthy eating habits early(Reference Bere and Klepp15). Nepper and Chai (2016) who carried out interviews with parents of 6–12-year-olds identified the following themes as barriers to their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption: parents’ time, cost of fruit and vegetables, children asking for junk food, children being picky eaters and their child’s early exposure to unhealthy eating(Reference Nepper and Chai17).

Underpinning interventions with psychological theory have been effective in bringing about behaviour change(Reference Painter, Borba and Hynes18). The Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) framework which incorporates the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behaviour (COM-B) model (Fig. 1)(Reference Michie, Atkins and West19) ascertains that for behaviour to occur there must be physical and psychological Capability, social and physical Opportunity, and reflective (thought processes) and automatic Motivation (intrinsic responses such as desires and impulses). To change a behaviour, one or more of the components need to be changed. The BCW framework consists of eight steps for behaviour change; however, this study will focus on the first five steps to identify the behaviours that are associated with increasing children’s fruit and vegetable consumption and will suggest possible intervention functions to target this behaviour. The COM-B model will be mapped out onto the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) (Fig. 1)(Reference Cane, O’Connor and Michie20). The TDF consists of fourteen domains across numerous theoretical constructs. These domains are ‘Knowledge’, ‘Skills’, ‘Social/Professional Role and Identity’, ‘Beliefs about Capabilities’, ‘Optimism’, ‘Beliefs about Consequences’, ‘Reinforcement’, ‘Intentions’, ‘Goals’, ‘Memory, Attention and Decision Processes’, ‘Environmental Context and Resources’, ‘Social Influences’, ‘Emotion’ and ‘Behavioural Regulation’. The TDF can be used to provide a framework of questions that will give an understanding of increasing children’s fruit and vegetable consumption. The components of the TDF that are identified as being pertinent to the behaviour of interest can then be mapped onto intervention functions and corresponding evidence-based behaviour change techniques. Most research on the application of the COM-B and the TDF to understand dietary behaviour has focused on adult populations(Reference Timlin, McCormack and Simpson21) or adults with pre-existing health conditions(Reference Keaver, Douglas and O’Callaghan22). There is limited research on applying the COM-B and TDF to understand children’s dietary behaviour. Porter et al.’s. (2023) application of the COM-B and TDF focused on the influences on families feeding practices in using effective strategies to increase their child eating vegetables(Reference Porter, Chater and Haycraft23). Using semi-structured interviews with parents of 2–4 years of age found that five of the six components of the COM-B were identified as components for change, supporting previous research that child food preferences, cost and food waste are barriers. In addition to previous findings, they identified that some feeding practices did not align with parental perceptions, and that knowledge regarding their child’s eating behaviour enabled them to persevere with feeding techniques. Specifically, they assessed that education, persuasion, training, enablement, modelling and environmental restructuring as suitable intervention functions. This study aims to build on this research in two ways: it will measure and address fruit and vegetables as both fruit and vegetables intake have been associated with health benefits(Reference Aune, Giovannucci and Boffetta5,Reference Wang, Li and Bhupathiraju6,Reference Guzek, Głąbska and Groele9) , and it will also focus on increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in children of primary school age.

Figure 1. COM-B model components mapped onto the corresponding TDF domains. COM-B, Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behaviour; TDF, Theoretical Domains Framework.

Rationale

This study utilised the BCW and TDF to explore behaviours related to increasing primary school-aged children’s fruit and vegetable consumption from a parent’s perspective. The BCW and TDF are effective models that have been applied to explore diet-related behaviour(Reference Timlin, McCormack and Simpson21,Reference Porter, Chater and Haycraft23) . However, as far as the authors are aware, they have not yet been applied to increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in this age group.

Latest figures in England indicate that 9·2 % of reception aged children (4–5 years) are living with obesity. This increases to 22·7 % of children by the time they leave primary school (aged 10–11 years)(24). As obesity correlates with low intake of fruit and vegetables(Reference Mekonnen, Tariku and Abebe7), targeting dietary interventions at primary school-aged children is critical. It is important to increase children’s fruit and vegetable consumption due to the impact that it has on their current and future physical and mental health. This study will specifically target children who are not eating the recommended amount of fruit and vegetables to help aid intervention development for this at-risk group. As primary school-aged children do not control the purchasing and availability of fruit and vegetables, this study is aimed at parental behaviours. Parents have a strong influence in shaping their child’s eating habits(Reference Scaglioni, Salvioni and Galimberti25), and research highlights the importance of targeting parental feeding behaviours(Reference Mahmood, Flores-Barrantes and Moreno26).

This study used the COM-B model to identify and explore parental factors that are associated with their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption, with findings being used to identify intervention functions that are likely to lead to the behaviour change of increased fruit and vegetable consumption in children. Specifically, the objectives were to explore parental perceived capability, opportunity and motivation to increase their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption and determine parental barriers and facilitators using the BCW and TDF to increase their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption and identify intervention functions that are likely to increase fruit and vegetable consumption in children.

Methods

Design

A qualitative design was used to elicit an understanding of behaviours surrounding COM-B on increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in primary school-aged children. Capability, Opportunity and Motivation were further divided using the TDF into the fourteen domains to provide a more detailed understanding of the behaviour. An online open-ended survey hosted on Gorilla was administered to capture in-depth information about parents’ thoughts and behaviours around their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption.

Participants

The ideal suggested sample size for participant-generated text is 10–50 participants(Reference Braun and Clarke27), and Francis et al., (2004) advise that for an elicitation study using open-ended questionnaires a sample size of 25 is ideal(Reference Francis, Eccles and Johnston28). Therefore, to extract enough data from the online surveys, a total of twenty-eight parents, both female (n 26) and male (n 2) aged between 29 and 51 years, participated in this study. Other qualitative design studies using the COM-B and TDF to understand health behaviours have used a similar number of participants(Reference Timlin, McCormack and Simpson21–Reference Porter, Chater and Haycraft23). Participants consisted of parents of primary school-aged children (children aged between 4 and 11 years). Participants were recruited via email advert through their child’s primary school, via online social media platforms, and to enhance recruitment, via Ulster University’s internal email system. Interested participants were able to access the survey by a link in the advert. Participants were able to complete the survey at any time, and there was no time limit imposed to complete the survey. The online survey included the consent form, the participant information sheet and debrief information. The inclusion criteria for the study were parents over the age of 18 years with a primary school-aged child who were not eating five portions of fruit and vegetables daily and live in the UK. The exclusion criteria were parents of children with food allergies or intolerances and parents of children with a learning disability or a health condition.

Procedure and materials

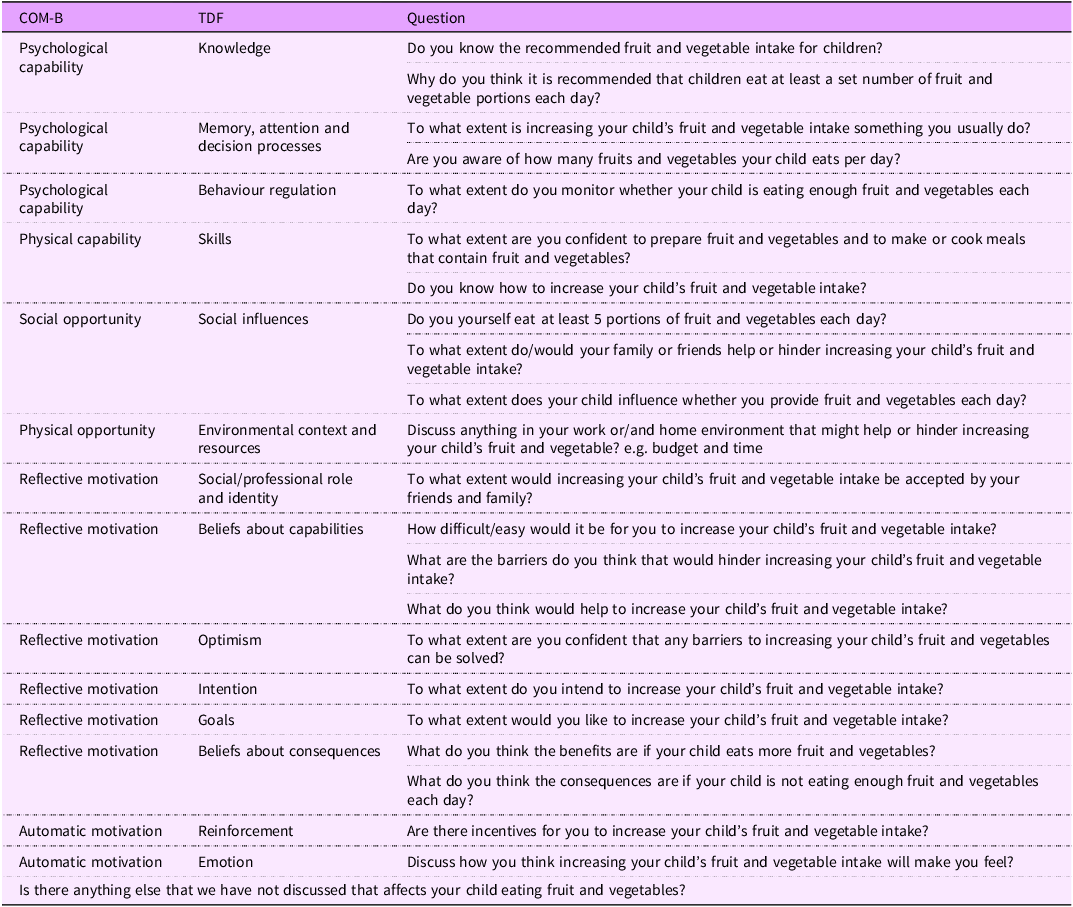

Participants were recruited via an advert that contained the link to the online survey. At the start of the online survey, participants were able to read the participant information form and provide consent if they wished to participate. Participants were informed that the study was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw at any time up until submission of their completed survey, that the survey was anonymous, that any personal data provided would be confidential and no identifiable information would be used in the study. Once consent was completed, participants were able to answer the survey questions. The survey consisted of demographic questions to explore any trends in responses, behavioural questions concerning their child’s current fruit and vegetable consumption, and twenty open-ended theoretical questions relating to their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption. The open-ended survey questions were developed with and informed by the COM-B model(Reference Michie, Atkins and West19) and then mapped onto each of the domains of the TDF(Reference Atkins, Francis and Islam29) (Table 1). Examples of the questions included ‘To what extent is increasing your child’s fruit and vegetable intake something you usually do?’, ‘Do you know how to increase your child’s fruit and vegetable intake?’ and ‘To what extent would increasing your child’s fruit and vegetable intake be accepted by your friends and family?’. At the end of the survey questions, participants were debriefed and signposted to resources if they had concerns about their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption.

Table 1. Open-ended survey questions devised from the COM-B model and Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF)

COM-B, Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behaviour.

Data analysis

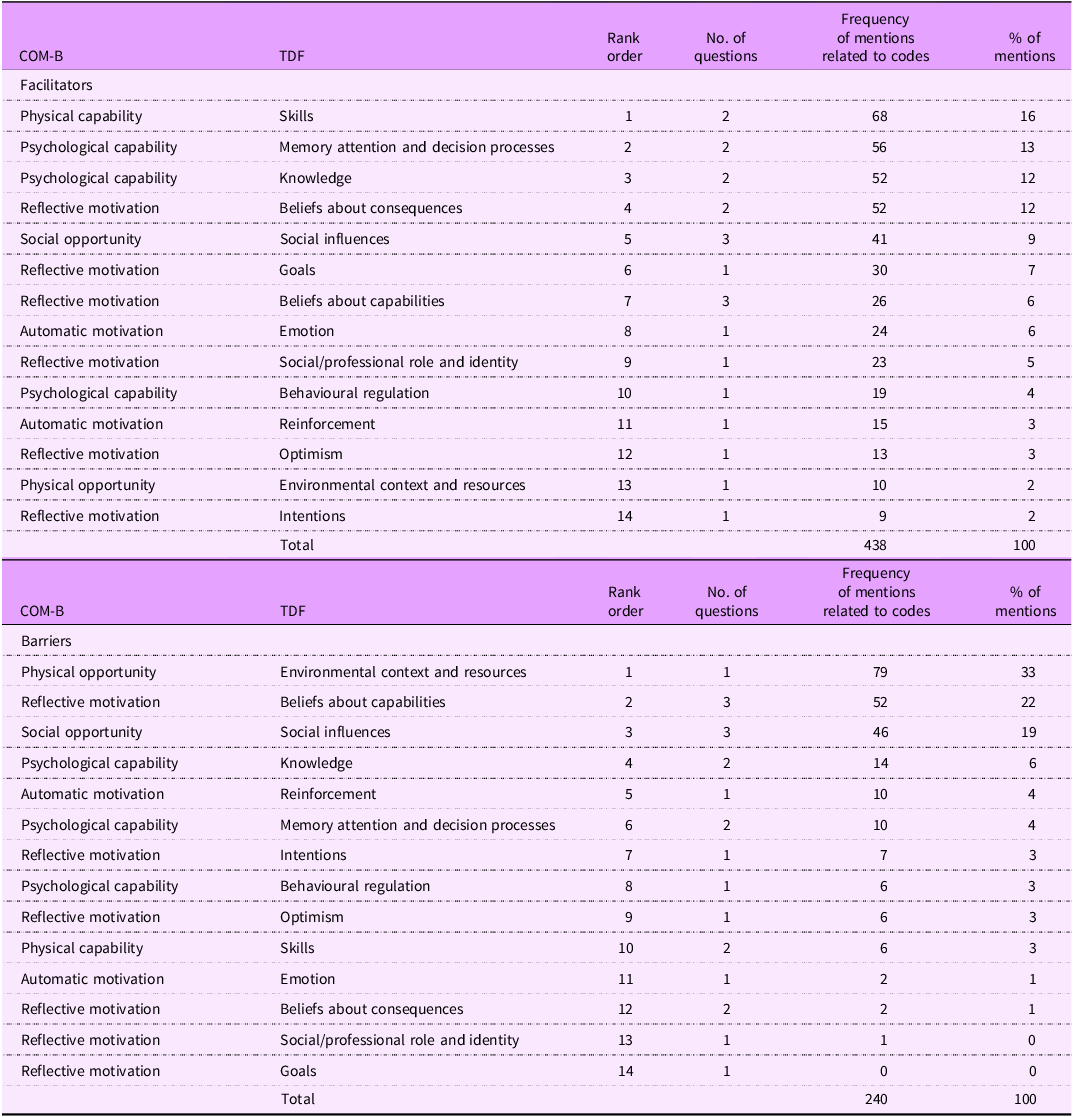

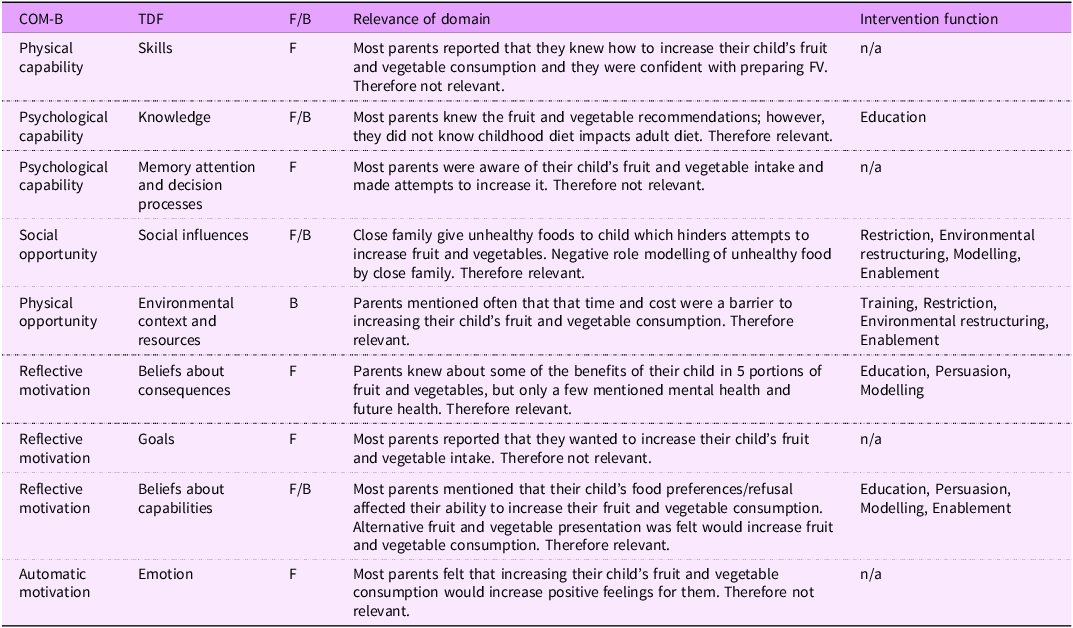

Qualitative data from the online survey were analysed and coded using thematic analysis(Reference Braun and Clarke30). The researcher (LG) conducted a thorough familiarisation with the dataset and kept a reflective diary throughout the process to ensure a clear overview of the material. Inductive coding was utilised on survey responses with each code identified as either a facilitator or barrier to increasing fruit and vegetable consumption. From the data coded, 10 % was cross-checked (with JD). There was a strong inter-rater agreement (83 %)(Reference McHugh31) on coding achieved with differences discussed and resolved. Once the codes had been agreed upon, summative content analysis(Reference Hsieh and Shannon32) was applied, where the researcher searched the text for occurrences of codes and frequency counts for each identified code. The TDF domains were judged based on the frequency count of coding for each TDF domain. TDF domains were then ranked-ordered as either a facilitator or as a barrier (see Table 2). From the COM-B and TDF analysis, a ‘behavioural diagnosis’ was formed (see Table 3). This was then mapped onto the nine intervention functions from the BCW(Reference Michie, Atkins and West19) namely, ‘Education’, ‘Persuasion’, ‘Incentivisation’, ‘Coercion’, ‘Training’, ‘Restriction’, ‘Environmental restructuring’, ‘Modelling’ and ‘Enablement’.

Table 2. Barriers and facilitators in rank order of mentions in relation to parental perspectives of their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption

COM-B, Capability (C), Opportunity (O), Motivation (M), Behaviour (B); TDF, Theoretical Domains Framework.

Information above the thick line represents the top-mentioned TDF domains. 80 % of mentions fell under these TDF domains.

Table 3. Behavioural diagnosis of increasing child’s fruit and vegetable intake using the BCW and COM-B

BCW, Behaviour Change Wheel; COM-B, Capability (C), Opportunity (O), Motivation (M), Behaviour (B); TDF, Theoretical Domains Framework; F, identified as a facilitator; B, identified as a barrier.

Results

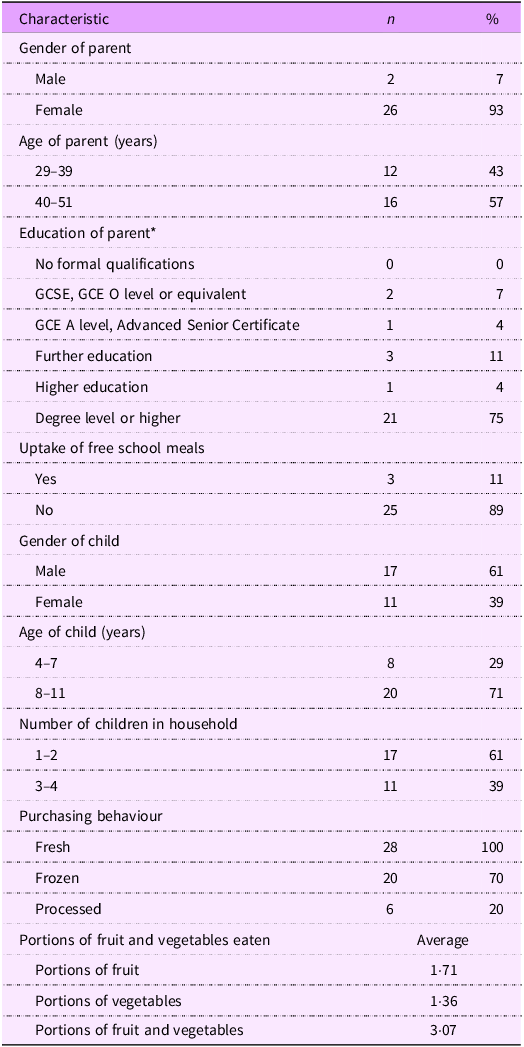

In total, twenty-eight participants participated in the study. Of the twenty-eight responses that completed the survey, one response contained missing data to ten out of the thirty-five questions (28·57 % missing). However, all data have been included in the analysis. Participants were both male (n 2; 7 %) and female (n 26; 93 %) with an age range of 29–51 years and an average age of 40·14 years (sd = 4·98). The children were both male (n 17; 60 %) and female (n 11; 40 %) with an average age of 8·12 (sd = 2·06) years. Of the participants’ children, 11 % were in receipt of free school meal entitlement. All participants reported that they purchased fresh fruit and vegetables with 71 % of participants purchasing frozen and 21 % of participants purchasing processed fruit and vegetables. Parents reported that their children were eating on average 3·07 portions of fruit and vegetables per d with slightly more fruit portions being eaten than vegetables (see Table 4 for summary of participant characteristics).

Table 4. Summary of participant characteristics (n 28)

* Higher education, BTEC (Higher), BEC, TEC, HNC, HND; further education, BTEC (Further/National), ONC, OND.

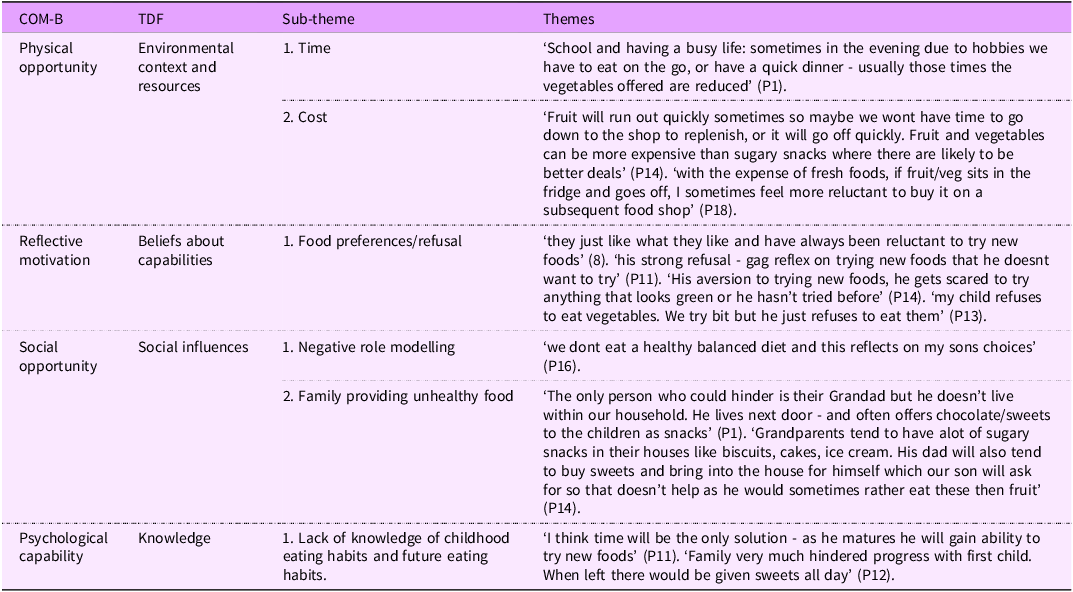

Table 2 represents the rank order of the barriers and facilitators of the COM-B and TDF domains relating to parental perspectives on their children’s fruit and vegetable consumption. All reports of barriers and facilitators to their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption were able to be mapped onto the TDF and COM-B. Of these, 65 % of mentions were identified to be a facilitator and 35 % were identified as a barrier. The TDF domains above the thick black line represent the key reported TDF domains and corresponding COM-B components which account for over 80 % of data. These cut of figures have been used in previous studies that have implemented the TDF with health-related behaviours(Reference Timlin, McCormack and Simpson21,Reference Lake, Browne and Rees33) . Of the facilitators, 80 % were captured by eight of the TDF domains: ‘skills’, ‘memory, attention and decision processes’, ‘knowledge’, ‘beliefs about consequences’, ‘social influences’, ‘goals’, ‘belief about capabilities’ and ‘emotion’. Likewise, 80 % of the barriers were captured by four of the TDF domains: ‘environmental, context and resources’, ‘beliefs about capabilities’, ‘social influences’ and ‘knowledge’. See Tables 5 and 6 for key COM-B facilitators and barriers and the sub-themes and quotes relating to these domains. The findings of these key domains and the corresponding COM-B components will be reported in more detail.

Table 5. Key COM-B facilitators, sub-themes and quotes from participants regarding increasing their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption

COM-B, Capability (C), Opportunity (O), Motivation (M), Behaviour (B); TDF, Theoretical Domains Framework.

Table 6. Key COM-B barriers, sub-themes and quotes from participants regarding increasing their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption

COM-B, Capability (C), Opportunity (O), Motivation (M), Behaviour (B); TDF, Theoretical Domains Framework.

Capability

Psychological capability

Psychological capability was identified as a facilitator and as a barrier to increasing their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption. These facilitators accounted for 25 % of mentions and fell into two of the fourteen TDF domains: ‘knowledge’ and ‘memory, attention and decision processes’. The barriers accounted for 6 % of mentions and were captured under the TDF domain: ‘knowledge’.

Knowledge

All but one participant (n 27; 96 %) were aware of how many portions of fruit and vegetables were recommended for children, and twenty-six (93 %) participants knew that the recommendations were for health benefits to their child: ‘Better overall health which affects their immune system, their oral health (teeth) and also their wellbeing’ (P1). One-quarter of parents (25 %) believed that fruit and vegetable intake would increase with age, for example, one parent reported that ‘I think time will be the only solution, as he matures, he will gain ability to try new foods’ (P11).

Memory, attention and decision processes

Memory, attention and decision processes were recorded when parents mentioned that they were aware of their child’s fruit and vegetable intake, made attempts to increase it and reported the mental effort of increasing fruit and vegetables. All parents were aware of their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption when they were at home, and 11 % of parents reported that they were unaware of fruit and vegetable consumption when their child was at school or with a caregiver such as a childminder or grandparent. Most participants attempted to try and increase their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption. One parent responded: ‘I try my best to offer multiple fruits and vegetables each day, however, some days this will not happen due to busy lifestyles, choosing convenience over quality when busy, etc’ (P18).

Physical capability

Physical capability was a key COM-B facilitator in this study for increasing their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption. This facilitator accounted for 16 % of mentions and came under the TDF domain: ‘skills’.

Skills

Skills were defined as the ability and competence to prepare and cook fruit and vegetables, along with the knowledge and ability to increase fruit and vegetable consumption. Most parents (89 %) felt confident in cooking and preparing fruit and vegetables, and parents reported that they were offering and encouraging their child to eat fruit and vegetables. For example, one parent reported that they ‘keep trying foods even if he indicated that he didn’t like (them) the last time he tried them’ and using ‘reward charts for trying new fruit and vegetables’ (P2). However, four participants reported that they did not know how to increase their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption.

Opportunity

Social opportunity

Social opportunity was reported as a facilitator (9 % of mentions) and as a barrier (19 % of mentions) to increasing their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption. The TDF domain that social opportunity falls under is ‘social influences’.

Social influences

Social influences were measured in terms of the influences that family and friends have on increasing their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption and the modelling of the desired behaviour. The most reported barriers that were recorded under social influences were that close family members, especially grandparents were giving their child unhealthy foods which hindered their ability to increase fruit and vegetables: ‘family is still counterproductive. one member actively gives child fizzy drinks, and junk food behind our back, to undermine progress’ (P12). In half of the participants (53 %), there was negative role modelling of unhealthy food eaten by close family members and the parents not eating five portions of fruit and vegetables themselves, such as one parent reported that ‘we don’t eat a healthy balanced diet, and this reflects on my son’s choices’ (P16). Only 46 % of parents were eating five portions of fruit and vegetables daily themselves. Some parents reported that family and friends actually helped to increase their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption.

Physical opportunity

Physical opportunity was the most frequently reported COM-B component in this study and was identified as a barrier to increasing fruit and vegetables with 33 % of mentions in the survey.

Environmental context and resources

Physical opportunity was defined as anything in the parent’s environment or situation that was associated with increasing their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption such as time, cost and availability. Nearly two-thirds of parents (64 %) mentioned time as a barrier to increasing fruit and vegetables. Parents reported that activities after school that their children are participating in and not being at home long enough affected their ability to offer fruit and vegetables. This was captured in one parent’s comment that ‘sometimes in the evening due to hobbies we have to eat on the go or have a quick dinner, usually those times the vegetables offered are reduced’ (P1).

Several parents also reported that fresh fruit and vegetables do not last long and therefore need replenishing throughout the week which is difficult due to busy lifestyles. Almost half (46 %) of parents mentioned that the cost of fruit and vegetables was a barrier to increasing their child’s consumption: ‘budget would be a big factor in increasing fruit and vegetables. I tend to look for multibuy deals for breakfast and lunches to save money’ (P5). Food waste of uneaten fruit and vegetables was also reported as a barrier.

Motivation

Reflective motivation

Reflective motivation was identified as a facilitator and as a barrier to increasing their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption. The facilitators accounted for 25 % of mentions and out of the six TDF domains that fall under reflective motivation, three of them were in the top 80 % of mentions. These were ‘beliefs about consequences’, ‘goals’ and ‘beliefs about capabilities’. The barriers accounted for 22 % of mentions and fell under the TDF domain: ‘beliefs about capabilities’.

Beliefs about consequences

Beliefs about consequences was coded when parents reported the anticipated outcomes of their children eating the recommended amount of fruit and vegetables each day. This TDF domain was a facilitator in increasing fruit and vegetables and accounted for 12 % of utterances. Parents reported that their children’s physical health, diet, sleep and concentration would be better if their children ate the recommended portions of fruit and vegetables. A few parents mentioned an improvement in mental health and only two parents reported the impact of fruit and vegetables on their child’s future health, for example, one parent reported that a ‘decreased immunity is the only consequence I can detect (in) them, this may also be caused by other factors’ (P15).

Goals

Goals were coded when parents mentioned in the survey that they want to or try to increase their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption such as ‘I fully intend to increase her fruit and vegetable intake’ (P5). The majority of parents (n 23; 82 %) reported that they would like to increase their child’s fruit and vegetable intake.

Beliefs about capabilities

Beliefs about capabilities was defined by how difficult parents felt that increasing their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption would be and their perceived ability to increase fruit and vegetables. Beliefs about capabilities were reported as a facilitator (6 %) and as a barrier (22 %) to increasing fruit and vegetable consumption. Many parents (64 %) felt that their child’s food preferences and food refusal affected their ability to increase their child’s fruit and vegetable intake: ‘they just like what they like and have always been reluctant to try new foods’ (P8). Several parents reported that if they provided an alternative presentation, blended fruit and vegetables and hid them in meals, this would increase their child’s intake. Almost a third (36 %) of parents felt that it would be easy to increase their child’s fruit and vegetable intake, especially if they had more time. Half of parents (50 %) mentioned that it would be difficult for them to increase their child’s fruit and vegetable intake, for example, ‘I would have to have to put quite a bit of effort into increasing my child’s vegetable intake as they claim to not enjoy the taste of many vegetables’ (P15).

Automatic motivation

Automatic motivation was identified as a facilitator to increasing fruit and vegetables. This component accounted for 6 % of mentions as a facilitator. Out of the two TDF domains that fell under automatic motivation. Emotion was identified as a facilitator and reinforcement was not identified as a key facilitator or a barrier to parents increasing their child’s fruit and vegetables consumption.

Emotion

Emotion was measured by parents’ reported feelings on how increasing their child’s fruit and vegetables would make them feel, with 82 % of parents mentioning that increasing their child’s fruit and vegetable intake would result in positive feelings for them. Such as, one parent reported that they would feel ‘happier because I feel I am helping him learn to be healthier and hopefully he will continue this as he gets older’ (P14) and another parent stated ‘I would love my child to eat more fruits and vegetables, it would make meal times calmer and more enjoyable’ (P24).

Behavioural diagnosis

Using the BCW to identify intervention functions, the key TDF domains and the corresponding COM-B components for facilitators and barriers were assessed as to whether they are relevant for behaviour change (see Table 3). The intervention functions identified as most likely to change parents increasing their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption are ‘Education’, ‘Persuasion’, ‘Training’, ‘Restriction’, ‘Environmental restructuring’, ‘Modelling’ and ‘Enablement’.

Discussion

This study sought to apply the BCW and TDF to explore parents’ perspectives increasing their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption. Data from parental responses identified that 80 % of the facilitators came under eight TDF domains (skills; memory, attention, and decision processes; knowledge; beliefs about consequences; social influences; goals; beliefs about capabilities; and emotions) and 80 % of barriers fell under only four TDF domains (environmental, context and resources; beliefs about capabilities; social influences; and knowledge). The results confirmed previous findings that parents’ dietary habits and child’s food preferences(Reference Bere and Klepp15,Reference Wolnicka, Taraszewska and Jaczewska-Schuetz16,Reference Porter, Chater and Haycraft23) , budget and time(Reference Nepper and Chai17,Reference Porter, Chater and Haycraft23) , were factors that were associated with increasing their children’s fruit and vegetable intake. Novel findings that were a barrier to increasing their children’s fruit and vegetable intake were incorrect parental beliefs and lack of knowledge.

Parents were knowledgeable about the recommended daily amount of fruit and vegetables for their children and the associated health benefits. Parents were also aware of how many fruits and vegetables their children were eating and knew how to prepare and cook fruit and vegetables, consistent with previous research which found that cooking and preparation skills were associated with a greater consumption of fruit and vegetables(Reference Hanson, Kattelmann and McCormack34). This highlights capability as a key facilitator in increasing fruit and vegetable consumption. However, a novel finding from this study was that a quarter of parents (25 %) reported/believed that their child’s fruit and vegetable intake will increase with age regardless. This may explain why only a small number of parents (32 %) intended to increase consumption. Given that considerable research shows that repeated exposure over time can increase fruit and vegetable consumption(Reference Appleton, Hemingway and Rajska35,Reference Nekitsing, Blundell-Birtill and Cockroft36) , it is possible that parents are confused as to the mechanisms/techniques that increase fruit and vegetable consumption with age. Therefore, it is suggested that future interventions target parental and skills around how to increase fruit and vegetables at home as their child ages. This highlights and supports the importance of targeting fruit and vegetable intake in children whilst they are young, especially considering that dietary behaviours in childhood are more likely to continue into adulthood(Reference Movassagh, Baxter-Jones and Kontulainen13).

Interestingly, it was not only the parents of children entitled to free school meals who reported that cost was a barrier. Almost half of parents surveyed felt that the cost and food waste from uneaten fruit and vegetables hindered their ability to increase their child’s consumption. This finding is supported by the research literature(Reference Nepper and Chai17). However, recent research has found that if households prioritise healthy eating, such as eating more fruit and vegetables, then they are better able to afford and consume more fruit and vegetables(Reference Stewart, Hyman and Dong37). In contrast, a UK study by Dogbe and Revoredo-Giha (2021) suggested that to increase fruit and vegetable consumption by 10 %, the price of fruit needs to decrease by 13 % and vegetables need to decrease by 21 %(Reference Dogbe and Revoredo-Giha38). Therefore, finding more affordable ways to eat fruit and vegetables is essential. Canned (processed) or frozen fruits and vegetables are lower or comparable to fresh fruit and vegetables and are therefore a cost-effective way to meet recommendations(Reference Miller and Knudson39). With 70 % of parents in this study reporting that they purchase frozen and only 20 % of parents reporting that they purchased processed fruit and vegetables, this may be a cost-effective alternative to increase their child’s consumption.

Close family members, particularly grandparents, were hindering increasing fruit and vegetable intake by offering unhealthy foods; this finding is consistent with previous research where grandparents have been found to negatively influence the dietary intake of their grandchildren(Reference Young, Duncanson and Burrows40). However, other research found evidence that grandparents generally provide healthy foods(Reference Jongenelis, Talati and Morley41). Given that about 50 % of grandparents are providing some proportion of childcare(Reference Hank and Buber42), strategies and interventions need to also be aimed beyond the home environment.

Parents were able to state the benefits of their child eating the recommended amount of fruit and vegetables; however, what this study found was that parents were not aware of the mental health benefits of fruit and vegetable consumption(Reference Guzek, Głąbska and Groele9) nor the impact that their child’s fruit and vegetable consumption could have on their future health(Reference Rampelli, Guenther and Turroni10). Research indicates that one in five children have a probable mental health disorder(43) and that incidences of type 2 diabetes is increasing in children(44). Therefore, it is crucial that early parental dietary interventions are prioritised. It is recommended that there is a focus on expanding parental knowledge to lead to a greater understanding of the many benefits of their children eating five portions of fruit and vegetables daily which may influence their intentions and attempts to increase intake.

The ‘behavioural diagnosis’ produced in this study indicates that five out of the six COM-B components are potential areas for change. The TDF domains that were deemed relevant are knowledge, social influences, environmental context and resources, beliefs about consequences, and beliefs about capabilities. The intervention functions relating to these domains are Education, Persuasion, Training, Restriction, Environmental restructuring, Modelling and Enablement. The BCW provides a systematic approach to behaviour change, and further research is recommended to identify appropriate behaviour change techniques, modes of delivery and policy categories that best target the intervention areas identified in this study(Reference Michie, Atkins and West19).

Limitations

The study was undertaken with a small sample size of parents (n 28); however, this is in line with previous dietary studies that incorporated the COM-B model and TDF(Reference Timlin, McCormack and Simpson21–Reference Porter, Chater and Haycraft23). Most parents in the sample were educated to at least a degree level (75 %), and only 11 % were entitled to free school meals. In 2023, 23·8 % school-aged children in the UK were eligible for free school meals(45). This would suggest that the participants in this study were of higher socio-economic status than the population as a whole. As the ethnicity of parents was not gathered, it is unknown whether the sample included parents from a range of cultural backgrounds. Therefore, the findings in this study may not be generalised to the general population. However, the aim of the study was to gain a greater depth of understanding of parental perspectives.

As the majority of participants were mothers, the results may not be representative of fathers’ perspectives. However, it is likely that mothers will engage most on this issue as they are generally the primary caregivers. This has been found in previous research that aimed to understand children’s dietary behaviour(Reference Kim, Park and Ma46). It is therefore suggested that future research aims to gather data from a greater diverse population representative of socio-economic status, level of education, ethnicity and gender. Researcher subjectivity may have been a limitation in the study; however, the researcher aimed to minimise this by keeping a reflective diary throughout analysis, and codes were cross-checked with a second individual (JD) who is experienced in qualitative research.

Lastly, the data collection method used in the study may have limitations such as the use of self-report and using an open-ended survey as opposed to focus groups or interviews. Self-reporting can be affected by recall and memory and influenced by various factors such as time, emotions and motivation(Reference Ravelli and Schoeller47). These factors could have affected reliability of parental responses. While focus groups and interviews can increase the desire for social acceptability(Reference Acocella48), this study was anonymous and online; therefore, participants would have been less likely to respond to social pressures.

Strengths

The COM-B is a successful theory-based model for understanding behaviour and has been utilised extensively in dietary change behaviour(Reference Timlin, McCormack and Simpson21,Reference Porter, Chater and Haycraft23) . Using the BCW allowed a systematic approach to identifying the barriers and facilitators to enable a ‘behavioural diagnosis’. To the researcher’s knowledge, this study was the first to develop a ‘behavioural diagnosis’ using the BCW and TDF to identify what needs to change to increase children’s fruit and vegetable consumption in primary school-aged children and link this to intervention functions to inform future intervention development.

Conclusion

The findings from this study using the BCW and TDF identified that for fruit and vegetable intake behaviour change to occur that ‘knowledge’, ‘social influences’, ‘environmental context and resources’, ‘beliefs about consequences’ and ‘beliefs about capabilities’ need to change. From the results obtained, five out of the six components of the COM-B model are required to increase fruit and vegetable consumption. The findings from this study recommend using the intervention functions identified to inform behaviour change techniques, modes of delivery and policy categories. As parents have a pivotal role in their child’s dietary intake, it is suggested that behaviour change techniques address the home environment as well as the wider home environment for successful behaviour change to increase children’s fruit and vegetable consumption.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the parents who gave their time to participate in this research.

Authorship

Both authors were responsible for the conception of the research idea and contributed to the study design and management. LG led data collection and undertook the analysis. Both authors were involved in drafting the paper and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics of human subject participation

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Ulster University School of Psychology Staff and Postgraduate Research Ethics Filter Committee (FCPSY-23–037). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients prior to taking part in the study.