Bipolar disorder is characterised by periods of depression and/or (hypo)mania, with periods of residual symptoms prior to recovery. Reference Perlis, Ostacher, Patel, Marangell, Zhang and Wisniewski1 Individuals with bipolar disorder often experience impairment in many areas of functioning, Reference Angst, Stassen, Clayton and Angst2–Reference Martínez-Arán, Vieta, Colom, Torrent, Sánchez-Moreno and Reinares7 with depressive symptoms accounting for a considerable portion of the burden of the illness. Reference Kessler, Akiskal, Ames, Birnbaum, Greenberg and Hirschfeld6,Reference De Dios, Ezquiaga, Garcia, Soler and Vieta8–Reference Baldessarini, Salvatore, Khalsa, Gebre-Medhin, Imaz and González-Pinto10 Given that pharmacological treatments often fail to bring patients with bipolar disorder to sustained remission, Reference Gitlin, Swendsen, Heller and Hammen11,Reference Harel and Levkovitz12 several adjunctive psychosocial interventions have been developed to treat depression in people with bipolar disorder, Reference Miklowitz13,Reference Lauder, Berk, Castle, Dodd and Berk14 including family-focused treatment (FFT Reference Miklowitz, Simoneau, George, Richards, Kalbag and Sachs-Ericsson15,Reference Rea, Tompson, Miklowitz, Goldstein, Hwang and Mintz16 ), cognitive–behavioural therapies (CBT Reference Cochran17–Reference Scott, Paykel, Morriss, Bentall, Kinderman and Johnson22 ) and interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT Reference Frank, Swartz and Kupfer23,Reference Frank, Kupfer, Thase, Mallinger, Swartz and Fagiolini24 ). One of largest randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of the efficacy of psychotherapy for depression in bipolar disorder was conducted in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Reference Sachs, Thase, Otto, Bauer, Miklowitz and Wisniewski25,Reference Miklowitz, Otto, Frank, Reilly-Harrington, Wisniewski and Kogan26 This found that FFT, IPSRT and CBT were equally effective in reducing the length of time until recovery from depressive episodes. Reference Miklowitz, Otto, Frank, Reilly-Harrington, Wisniewski and Kogan26 Despite these available treatments, many individuals with bipolar disorder recover slowly. Reference Goodwin and Jamison4,Reference Mitchell and Malhi27–Reference Gitlin29

Previous studies have suggested that factors such as low thyroid functioning, Reference Cole, Thase, Mallinger, Soares, Luther and Kupfer30 familial expressed emotion, Reference Miklowitz, Goldstein, Nuechterlein, Snyder and Mintz31 low social support, Reference Johnson, Winett, Meyer, Greenhouse and Miller32 negative life events Reference Johnson and Miller33 and extreme thinking Reference Stange, Sylvia, da Silva Magalhães, Miklowitz, Otto and Frank34 are associated with a longer course of bipolar depression, but researchers and clinicians have called for an improved understanding of which patients are most likely to respond to psychosocial treatments. Reference Strakowski35 One characteristic that may be promising for identifying individuals at risk for poorer outcomes is affective instability, defined as the tendency to experience mood shifts over time that are frequent (highly variable, changing from moment to moment) and large (extreme or very intense), rapidly shifting from positive or neutral states to intensely negative affective states. Reference Trull, Solhan, Tragesser, Jahng, Wood and Piasecki36,Reference Berenbaum, Bredemeier, Boden, Thompson and Milanak37 Affective instability is hypothesised to play a role in mood disorders, Reference Ebner-Priemer, Eid, Kleindienst, Stabenow and Trull38 with previous studies demonstrating that affective instability is elevated in depression and anxiety. Reference McConville and Cooper39–Reference Thompson, Mata, Jaeggi, Buschkuehl, Jonides and Gotlib41 One study reported that affective instability (assessed by an item in a personality disorder interview) was associated with having a family history of mania or depression. Reference Berenbaum, Bredemeier, Boden, Thompson and Milanak37 Degree of mood lability distinguished between offspring with bipolar disorder from offspring without bipolar disorder whose parents have bipolar disorder, and healthy children of healthy parents. Reference Birmaher, Goldstein, Axelson, Monk, Hickey and Fan42 However, to our knowledge, no psychotherapy studies in bipolar disorder have evaluated affective instability as a predictor of the duration of mood episodes or as a moderator of treatment response.

Affective instability is associated with several characteristics that suggest that it may hold promise as a predictor of outcome in bipolar disorder. Individuals who are affectively unstable are often emotionally reactive to situational stimuli and have an attenuated ability to regulate their emotions. Reference Thompson, Dizen and Berenbaum43 Indeed, research has demonstrated that individuals who are affectively unstable have poorer physiological capacity for emotion regulation Reference Koval, Ogrinz, Kuppens, Van den Bergh, Tuerlinckx and Sütterlin44 and display dysfunctional prefrontal network activity during cognitive reappraisal of negative emotions. Reference Schulze, Hauenstein, Grossmann, Schmahl, Prehn and Fleischer45 Affective instability is also associated with neuroticism Reference Miller, Vachon and Lynam46,Reference Miller and Pilkonis47 and is a hallmark feature of borderline personality disorder, Reference Nica and Links48 which is both commonly comorbid with bipolar disorder and associated with a poorer course of illness in bipolar disorder. Reference Dunayevich, Sax, Keck, McElroy, Sorter and McConville49,Reference Zimmerman, Chelminski, Young, Dalrymple and Martinez50

The goal of the current study was to evaluate whether affective instability in bipolar disorder (instability in symptoms of depression and mania) is associated with a lower likelihood of recovery, and a longer time until recovery, from a depressive episode of bipolar I or II disorder. We also investigated whether affective instability moderated the effects of psychosocial treatment on likelihood of recovery and time until recovery from depression. Because intensive psychotherapies provide behavioural skills for managing fluctuations in mood, we hypothesised that the effects of intensive psychotherapy (FFT, IPSRT or CBT, compared with a brief psychoeducational comparison condition) on likelihood of recovery and time until recovery would be stronger among patients with more rather than less affective instability. This study represents one of the first studies to use a clinical sample of individuals with mood disorders to assess a validated measure of affective instability (the extent to which consecutively measured moods differ from each other) over a period of time, which may be more important than affective variability (a measure of shifts in affect irrespective of when the shifts took place) as often has been used in the past. Reference Ebner-Priemer, Eid, Kleindienst, Stabenow and Trull38,Reference Jahng, Wood and Trull51

Method

Study design and participants

Participants were out-patients enrolled in the RCT comparing the efficacy of psychotherapy and collaborative care treatment as part of STEP-BD. Reference Miklowitz, Otto, Frank, Reilly-Harrington, Wisniewski and Kogan26 STEP-BD is a National Institute of Mental Health-sponsored multicentre naturalistic study of the effectiveness of treatments for bipolar disorder. Reference Sachs, Thase, Otto, Bauer, Miklowitz and Wisniewski25 Inclusion criteria for the RCT included: (a) 18 years of age or older, (b) DSM-IV criteria 52 for bipolar I or II disorder with a current (during the prior 2 weeks) major depressive episode, (c) current treatment with a mood stabiliser, (d) not currently undergoing psychotherapy, (e) speaking English, and (f) ability and willingness to give informed consent. Exclusion criteria were (a) requiring immediate treatment for a DSM-IV substance or alcohol use or dependence disorder (excluding nicotine), (b) current or planned pregnancy in the next year, (c) intolerance, non-response or contraindication to bupropion or paroxetine, and (d) requiring dose changes in antipsychotic medications. The study was reviewed and approved by the human research institutional review boards of all participating universities.

The subsample of 252 patients in the present report (Table 1) were selected from 293 out-patients enrolled in the RCT based on having completed at least four assessments with the Clinical Monitoring Form (CMF) Reference Sachs, Guille and McMurrich53 prior to recovery from depression (if recovered) or the end of the study (if not recovered). The other 41 individuals in the original sample of 293 had completed fewer than 4 CMFs prior to recovery (for those who recovered) or the end of the study (for those who did not recover); fewer than four observations precluded obtaining a reliable measure of affective instability. Reference Jahng, Wood and Trull51 In the sample of 41 excluded patients, fewer patients were taking lithium (χ2 = 5.12, P = 0.02), and more were taking other mood stabilisers (χ2 = 9.62, P<0.01). The 252 patients who participated were less likely to have a comorbid anxiety disorder than the 41 who were excluded (χ2 = 4.38, P = 0.04). No other patient characteristics differed between these groups (χ2s<2.51, ts<1.14, Ps>0.11).

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of 252 patients with bipolar disorder who are depressed a

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 40.57 (11.70) |

| Female, % | 56 |

| Ethnicity, % | |

| White | 93 |

| African-American/Black | 4 |

| Asian-Pacific Islander | 1 |

| Other | <1 |

| Hispanic ethnicity, % | 3 |

| Education >1 year of college, % | 80 |

| Income <US$29999, % | 69 |

| Marital status, % | |

| Married | 32 |

| Never married | 37 |

| Separated/divorced | 30 |

| Widowed | 2 |

| Diagnosis, % | |

| Bipolar I disorder | 61 |

| Bipolar II disorder | 39 |

| >10 Previous depressive episodes, % | 52 |

| >10 Previous manic episodes, % | 62 |

| Age at illness onset, years: mean (s.d.) | 22.16 (9.94) |

| Baseline depression symptoms, mean (s.d.) | 7.07 (2.32) |

| Baseline mania symptoms, mean (s.d.) | 1.13 (1.02) |

| Baseline Global Assessment of Functioning score, mean (s.d.) |

61.87 (10.86) |

| Medication, % | |

| Lithium | 36 |

| Atypical antipsychotic | 28 |

| Anticonvulsant | 53 |

| Benzodiazepine | 24 |

| Antidepressants | 44 |

| Stimulants | 1 |

| Valproate | 34 |

| Other mood stabilisers | 25 |

| Comorbid diagnoses, % | |

| Anxiety disorder, current | 43 |

| Substance misuse/dependence, current | 18 |

| Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, current | 9 |

| Any lifetime comorbid disorder | 83 |

a. Percentages are not always based on 252 patients because of missing data (see Miklowitz et al Reference Miller and Pilkonis47 ).

Procedures and outcomes

Patients were diagnosed with bipolar disorder by study psychiatrists using the Affective Disorders Evaluation. Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams54,Reference Sachs55 A second interviewer verified the results using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (version 5.0 Reference Sachs, Thase, Otto, Bauer, Miklowitz and Wisniewski25,Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller56 ). The 252 participants included in the present report were randomly assigned to an intensive psychotherapy (n = 141; CBT: n = 66, IPSRT: n = 54 or FFT: n = 21) or to the collaborative care (n = 111) control condition (for more information about these treatments see Frank et al, Reference Frank, Kupfer, Thase, Mallinger, Swartz and Fagiolini24 Otto et al, Reference Otto, Reilly-Harrington, Knauz, Henin, Kogan and Sachs57 Miklowitz Reference Miklowitz58 and Miklowitz et al Reference Miklowitz, Otto, Frank, Reilly-Harrington, Wisniewski and Kogan26 ). Collaborative care was a minimal psychosocial intervention consisting of three 50 min individual sessions completed within 6 weeks of randomisation. It was intended to provide a brief version of the most common strategies shown to benefit patients with bipolar disorder, and included psychoeducation about bipolar disorder and development of a relapse prevention contract. Reference Miklowitz58 The intensive psychosocial treatments consisted of up to 30 sessions of 50 min conducted by therapists who received training and supervision from nationally recognised experts in the specific intensive treatments. Reference Miklowitz, Otto, Frank, Reilly-Harrington, Wisniewski and Kogan26

Measures

CMF

The primary outcome measure in the present study was patients' clinical recovery status, which was assessed via the CMF Reference Miklowitz, Otto, Frank, Reilly-Harrington, Wisniewski and Kogan26 by psychiatrists treating patients at regular out-patient pharmacotherapy visits that occurred during the course of the psychosocial treatment trial (mean 9.67 CMFs completed; range 4–40). The CMF is a measure of the severity of DSM-IV mood symptoms and clinical status that has been well-validated. Reference Perlis, Ostacher, Patel, Marangell, Zhang and Wisniewski1,Reference Sachs, Thase, Otto, Bauer, Miklowitz and Wisniewski25,Reference Miklowitz, Otto, Frank, Reilly-Harrington, Wisniewski and Kogan26,Reference Sachs, Guille and McMurrich53,Reference Otto, Simon, Wisniewski, Miklowitz, Kogan and Reilly-Harrington59 The CMF was used as the primary outcome measure in STEP-BD and other clinical trials because of its ability to be non-intrusively implemented by the treating psychiatrist as part of standard clinical care. Its benefits include reduced time for administration and greater acceptability by patients, with the benefits of capturing much of the same information about affective symptoms as formal rating scales. Indeed, the CMF symptom measures are strongly correlated with ratings produced by other rating scales. Reference Sachs, Guille and McMurrich53 Psychiatrists rated patients' symptoms during the acute stabilisation period (first four medication visits held once every 1 to 2 weeks) after entry into the trial, followed by regularly scheduled medication management visits thereafter. Intraclass interrater reliability coefficients (compared with gold standard ratings for CMF depression and mania items) ranged from 0.83 to 0.99. Reference Miklowitz, Otto, Frank, Reilly-Harrington, Wisniewski and Kogan26

Clinical status (for example ‘recovered’) is based on the presence of DSM-IV criteria for episodes of depression or mania/hypomania. Recovered status is defined as <2 moderate symptoms of depression for >8 of the previous weeks. The CMF also yielded the depression and mania symptom severity scores (sum of the severity of all depression/mania symptoms) at study entry, and the mean symptom severity scores, which were computed across follow-up prior to recovery (for those who recovered) or the end of 365 days (for those who did not recover).

Affective instability variables were computed for symptoms of depression and mania from scores on the CMF. The recommended measure of affective instability is the root mean square successive difference (rMSSD) score, which reflects the extent to which consecutively measured moods differ from one another. Reference Ebner-Priemer, Eid, Kleindienst, Stabenow and Trull38,Reference Jahng, Wood and Trull51 The rMSSD reflects both the size and the temporal order of changes in affect, making it a superior measure of affective instability relative to other measures such as the standard deviation of scores, which does not account for the temporal order of affective changes. Reference Jahng, Wood and Trull51 The MSSD was computed for each symptom of depression and mania from consecutively assessed CMFs. For each symptom, the squared difference between symptom severity at each consecutive time point (for example squared difference between time 1 and time 2, time 2 and time 3, etc.) was computed; these squared differences were then averaged for each symptom for each participant across the study. We then computed the mean rMSSD across depressive symptoms and the mean rMSSD across mania symptoms (prior to recovery or end of study), which served as the measures of affective instability and as the primary predictor variables in this study. Depression and mania instability scores were moderately correlated (r = 0.43, P<0.001). Previous reports have demonstrated the construct validity of affective instability Reference Jahng, Wood and Trull51,Reference Ebner-Priemer, Eid, Kleindienst, Stabenow and Trull38 and have shown that instability of mood symptoms is relatively consistent over time. Reference McConville and Cooper60 In our sample, affective instability was not associated with diagnoses of either anxiety disorders or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the associations between affective instability and likelihood of recovery and time until recovery, we conducted logistic regressions and Cox proportional hazards models respectively. All analyses were by intention-to-treat. Patients were included until their final assessment point with a maximum of 365 days in the study Reference Miklowitz, Otto, Frank, Reilly-Harrington, Wisniewski and Kogan26 (mean 291.09 days, s.d. = 90.77). Analyses controlled for treatment condition, baseline symptoms of depression and mania, and average symptoms of depression and mania prior to recovery (for individuals who recovered) or the end of 365 days (for individuals who did not recover). This improved the ability to conclude that associations between affective instability and course of depression were a result of the instability, rather than the intensity, of affect. Reference Ebner-Priemer, Eid, Kleindienst, Stabenow and Trull38

The proportionality of risk assumption was not upheld for survival analyses involving depression symptom instability and number of assessments, so the time-dependent covariates (interaction terms between time and depression symptom stability and number of assessments) were included in the relevant analyses. Reference Tabachnik and Fidell61 The results were consistent regardless of whether these terms were included in the model. Odds ratios (ORs) less than one indicate lower likelihood of recovery and greater time until recovery. Prior to evaluating affective instability variables as moderators of treatment effects, we determined whether there were significant effects of treatment condition on the likelihood of recovery and time until recovery. Reference Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn and Agras62 Moderation analyses controlled for the same variables noted above, followed by the main effects of treatment and affective instability, and the interaction term between these two variables.

Results

Clinical and demographic characteristics are displayed in Table 1 (for the characteristics of the original sample see Miklowitz et al Reference Miklowitz, Otto, Frank, Reilly-Harrington, Wisniewski and Kogan26 ).

Effects of affective instability on recovery from depression

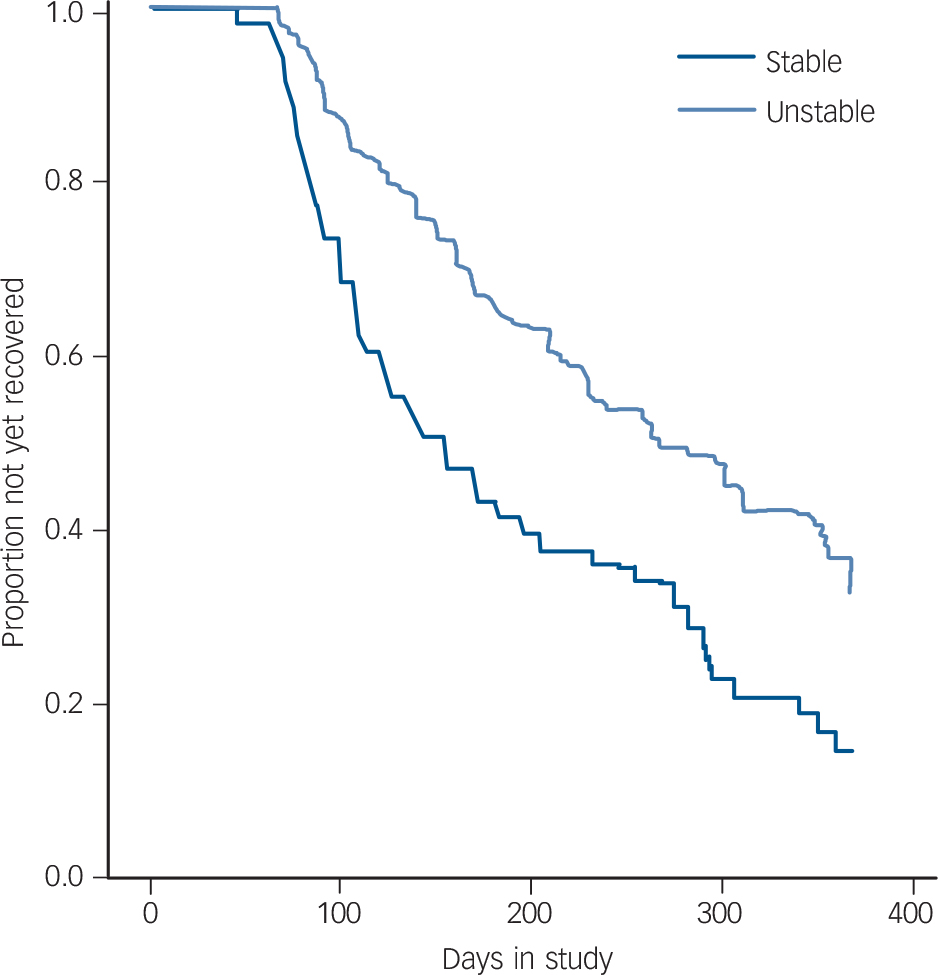

Results of primary analyses are presented in Tables 2 (depression symptom instability) and 3 (mania symptom instability). Controlling for treatment condition and other affective variables, depressive symptom instability predicted a significantly lower likelihood of recovery and a longer time until recovery from depression (Fig. 1). Correspondingly, analyses indicated that a one-standard deviation increase in stability of depressive symptoms was associated with a 60% greater likelihood of recovery.

Table 2 Logistic regression and Cox regression analyses evaluating depression symptom instability as predictor of likelihood of recovery and time until recovery from depression a

| Step and predictor | B | Wald | OR (95% CI) | P | ΔR 2b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic regression: predicting recovery | |||||

| Step 1: treatment group | 0.16 | 0.22 | 1.17 (0.61–2.26) | 0.64 | 0.02 |

| Step 2 | |||||

| Time in study | 0.01 | 34.73 | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | <0.01 | 0.42 |

| Number of assessments | −0.15 | 20.64 | 0.86 (0.81–0.92) | <0.01 | |

| Initial depression symptoms | 0.09 | 1.23 | 1.10 (0.93–1.29) | 0.27 | |

| Initial mania symptoms | 0.18 | 0.95 | 1.20 (0.83–1.73) | 0.33 | |

| Average depression symptoms | −0.36 | 9.14 | 0.70 (0.56–0.88) | <0.01 | |

| Average mania symptoms | −0.46 | 4.35 | 0.63 (0.41–0.97) | 0.04 | |

| Step 3: depression symptom instability | −0.47 | 5.47 | 0.63 (0.42–0.93) | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Cox regression: predicting time until recovery | |||||

| Step 1: treatment group | 0.10 | 0.28 | 1.09 (0.79–1.51) | 0.60 | 0.02 |

| Step 2 | |||||

| Initial depression symptoms | 0.09 | 3.35 | 1.09 (0.99–1.20) | 0.07 | 0.46 |

| Initial mania symptoms | 0.08 | 0.65 | 1.08 (0.90–1.30) | 0.42 | |

| Average depression symptoms | −0.22 | 13.87 | 0.80 (0.72–0.90) | <0.01 | |

| Average mania symptoms | −0.22 | 3.84 | 0.80 (0.64–1.00) | 0.05 | |

| Number of assessments | −1.10 | 27.76 | 0.33 (0.22–0.50) | <0.01 | |

| Number of assessments × time | 0.19 | 22.82 | 1.20 (1.12–1.30) | <0.01 | |

| Depression symptom instability × time | 0.48 | 6.18 | 1.62 (1.11–2.37) | 0.01 | |

| Step 3: depression symptom instability | −2.94 | 9.28 | 0.05 (0.01–0.35) | <0.01 | 0.03 |

a. n = 252. Treatment group is intensive psychosocial treatment (coded 1) v. collaborative care (coded 0). Average symptoms represent mean Clinical Monitoring Form (CMF) symptoms across follow-up period prior to recovery (for those who recovered) or end of study (for those who did not recover). Number of assessments is the number of CMFs completed prior to recovery (for those who recovered) or end of study (for those who did not recover). Symptom instability is the mean square successive difference in symptoms occurring prior to recovery (for those who recovered) or end of study (for those who did not recover). The proportionality of risk assumption was not upheld for survival analyses involving depression symptom instability and number of assessments, so the time-dependent covariates (interaction terms between time and these predictors) are included in Cox regression analyses. Reference Tabachnik and Fidell61

b. Change in R 2 for logistic regressions represents Nagelkerke R 2 change since previous step, an estimate of the increment in variance in the probability of recovery accounted for by the predictors tested since the previous step. Change in R 2 for Cox regressions represents Cox-Snell R 2 change since previous step, an estimate of the relative association between survival and the predictors tested since the previous step. Reference Tabachnik and Fidell61

Table 3 Logistic regression and Cox regression analyses evaluating mania symptom instability as predictor of likelihood of recovery and time until recovery from depression a

| Step and predictor | B | Wald | OR | P | ΔR 2b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic regression: predicting recovery | |||||

| Step 1: treatment group | 0.12 | 0.14 | 1.13 (0.59–2.19) | 0.71 | 0.02 |

| Step 2 | |||||

| Time in study | 0.01 | 35.15 | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | <0.01 | 0.42 |

| Number of assessments | −0.14 | 19.17 | 0.87 (0.82–0.93) | <0.01 | |

| Initial depression symptoms | 0.09 | 1.17 | 1.09 (0.93–1.29) | 0.28 | |

| Initial mania symptoms | 0.14 | 0.57 | 1.15 (0.80–1.65) | 0.45 | |

| Average depression symptoms | −0.44 | 14.97 | 0.65 (0.52–0.81) | <0.01 | |

| Average mania symptoms | −0.09 | 0.11 | 0.91 (0.52–1.60) | 0.75 | |

| Step 3: mania symptom instability | −0.53 | 4.21 | 0.59 (0.36–0.98) | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Cox regression: predicting time until recovery | |||||

| Step 1: treatment group | 0.16 | 0.92 | 1.17 (0.85–1.63) | 0.34 | 0.02 |

| Step 2 | |||||

| Initial depression symptoms | 0.08 | 3.15 | 1.08 (0.99–1.18) | 0.08 | 0.41 |

| Initial mania symptoms | 0.09 | 0.83 | 1.09 (0.91–1.31) | 0.36 | |

| Average depression symptoms | −0.29 | 23.05 | 0.75 (0.67–0.85) | <0.01 | |

| Average mania symptoms | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.02 (0.75–1.39) | 0.89 | |

| Number of assessments | −0.93 | 21.10 | 0.40 (0.27–0.59) | <0.01 | |

| Number of assessments × time | 0.16 | 17.09 | 1.17 (1.09–1.26) | <0.01 | |

| Step 3: mania symptom instability | −0.33 | 6.34 | 0.72 (0.56–0.93) | 0.01 | 0.03 |

a. n = 252. Treatment group is intensive psychosocial treatment (coded 1) v. collaborative care (coded 0). Average symptoms represent mean Clinical Monitoring Form (CMF) symptoms across follow-up period prior to recovery (for those who recovered) or end of study (for those who did not recover). Number of assessments is the number of CMFs completed prior to recovery (for those who recovered) or end of study (for those who did not recover). Symptom instability is the mean square successive difference in symptoms occurring prior to recovery (for those who recovered) or end of study (for those who did not recover). The proportionality of risk assumption was not upheld for survival analyses involving number of assessments, so the time-dependent covariates (interaction terms between time and these predictors) are included in Cox regression analyses. Reference Tabachnik and Fidell61

b. R 2 for logistic regressions represents Nagelkerke R 2 change since previous step, an estimate of the increment in variance in the probability of recovery accounted for by the predictors tested since the previous step. Change in R 2 for Cox regressions represents Cox-Snell R 2 change since previous step, an estimate of the relative association between survival and the predictors tested since the previous step. Reference Tabachnik and Fidell61

Fig. 1 Cox regression of depression symptom instability predicting time until recovery from depression.

Symptom instability was used as a continuous variable in analyses but is presented using a median split for illustrative purposes in the figure.

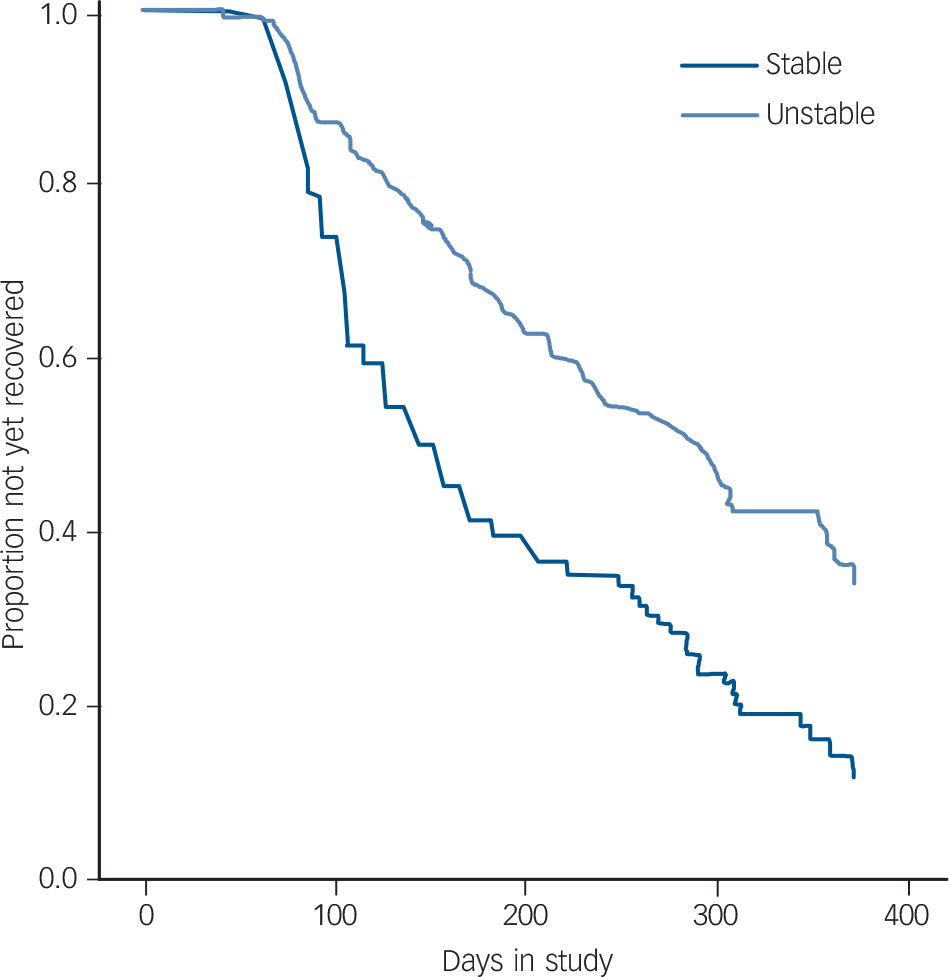

Similarly, manic symptom instability predicted a significantly lower likelihood of recovery and a longer time until recovery from depression (Fig. 2). A one-standard deviation increase in stability of manic symptoms was associated with a 69% greater likelihood of recovery.

Fig. 2 Cox regression of mania symptom instability predicting time until recovery from depression.

Symptom instability was used as a continuous variable in analyses but is presented using a median split for illustrative purposes in the figure.

Notably, all results remained consistent after controlling for number of psychosocial treatment sessions, bipolar I or II status, age, gender, number of lifetime episodes of depression and mania/hypomania, anxiety disorders, ADHD, medical conditions, history of rapid cycling and age at onset of bipolar disorder. When controlling for duration of illness, the effects of manic symptom instability on likelihood of recovery (OR = 0.50, 95% CI 0.20–1.12, P = 0.11) and time until recovery (OR = 0.78, 95% CI 0.52–1.08, P = 0.12) were reduced to non-significance, likely as a result of reduced power due to missing data (n = 217).

Affective instability as a moderator of effects of treatment on recovery from depression

In this sample, as in the larger sample of 293, Reference Miklowitz, Otto, Frank, Reilly-Harrington, Wisniewski and Kogan26 individuals who received an intensive psychotherapy were more likely to recover from depression (OR = 1.69, 95% CI 1.01–2.83, P<0.05) and recovered more quickly (OR = 1.39, 95% CI 1.01–1.92, P<0.05) than individuals who received collaborative care.

Depressive symptom instability did not moderate the effects of treatment on likelihood of recovery (OR = 1.52, 95% CI 0.71–3.25, P = 0.28) or time until recovery from depression (OR = 1.14, 95% CI 0.76–1.71, P = 0.53). Similarly, manic symptom instability did not moderate the effects of treatment on likelihood of recovery (OR = 0.90, 95% CI 0.43–1.88, P = 0.78) or time until recovery (OR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.69–1.37, P = 0.86). When controlling for depressive or manic instability, the effects of treatment on recovery were reduced to non-significance.

Discussion

Main findings

Consistent with our hypotheses, among patients who are depressed and have bipolar I or II disorder and are treated with medications and different intensities of psychotherapy, affective instability predicted a lower likelihood of recovery from depression and a greater time until recovery. These results were similar for instability of depressive symptoms and for instability of manic symptoms across the study period. Notably, depressive and manic symptom instability continued to predict a more severe course of depression even after accounting for initial depression severity, average symptom intensity across follow-up and other clinical and demographic characteristics, suggesting that patients whose condition was affectively unstable did not experience a longer course of depression simply as a result of experiencing more severe symptoms overall. In contrast, affective instability did not moderate the effect of psychosocial treatments on recovery from depression. Although previous reports have documented that residual symptoms predict episode recurrence in bipolar disorder, Reference Perlis, Ostacher, Patel, Marangell, Zhang and Wisniewski1 this is the first study to demonstrate that depressive and manic instability are associated with a poorer course of bipolar depression.

Affective instability may in part represent the effects of comorbid personality. Indeed, a large proportion (at least 28%) of patients with bipolar disorder meet criteria for borderline personality disorder when in remission. Reference George, Miklowitz, Richards, Simoneau and Taylor63 Other correlates of affective instability may be germane, such as chaotic social environments or medical disorders – such as thyroid dysfunction – that may cause affective instability.

Individuals whose condition was affectively unstable showed more rapid time to recovery in intensive therapy than in collaborative care, as was true for the rest of the sample. Nonetheless, receiving more targeted treatments or more frequent treatment monitoring would have improved their course of depression. For example, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy Reference Deckersbach, Hölzel, Eisner, Stange, Peckham and Dougherty64 and dialectical behavioural therapy, Reference Linehan65 both of which focus on tolerating and regulating aversive emotions, may be particularly useful for individuals with bipolar disorder with affective instability.

Possible explanation for our findings

The mechanisms whereby affective instability leads to a longer course of bipolar depression remain to be explored. It seems likely that these patients have poorer emotion regulation skills (see for example Thompson et al Reference Thompson, Dizen and Berenbaum43 ) or that they frequently experience strong emotions that are difficult to regulate (see for example Schulze et al Reference Schulze, Hauenstein, Grossmann, Schmahl, Prehn and Fleischer45 ). Alternatively, their use of emotion regulation strategies may be ineffective in downregulating negative emotions as a result of deficits in executive functioning (see for example Pe et al; Reference Pe, Raes and Kuppens66 Schulze et al; Reference Schulze, Hauenstein, Grossmann, Schmahl, Prehn and Fleischer45 Martínez-Arán et al; Reference Martínez-Arán, Vieta, Colom, Torrent, Sánchez-Moreno and Reinares7 Robinson et al Reference Robinson, Thompson, Gallagher, Goswami, Young and Ferrier67 ). Given the well-documented effects of mood symptoms in contributing to the occurrence of stressful events, Reference Liu and Alloy68 it is possible that frequent mood shifts could lead to secondary interpersonal difficulties (such as a romantic partner becoming irritated with the patient's behaviour) or achievement problems (such as starting a project at work one week but failing to follow through with it the next week when symptoms worsened), which would serve as additional stressors that could exacerbate or maintain the patient's depression. Implementing effective psychological treatments, then, will require observing moods on a rapidly changing basis; weekly sessions may be inadequate for this purpose. These possibilities should be explored in future research.

Strengths and limitations

This study had several strengths, including the use of a clinician-rated scale of mood symptoms with up to 1 year of follow-up, and the use of a large sample of treatment-seeking adults who entered the study close to the beginning of their depressive episodes, thus enhancing the clinical applicability of these results to adults presenting for treatment for depression. This also is one of the first studies that used a clinical sample of individuals with mood disorders to assess a validated measure of affective instability. Reference Ebner-Priemer, Eid, Kleindienst, Stabenow and Trull38,Reference Jahng, Wood and Trull51 Although the CMF has been well-validated with other established mood rating scales, we did not use other mood disorder rating scales frequently enough to create comparable measures of affective instability.

Several other limitations should be noted. First, although our use of multiple observations of clinician-assessed mood symptoms was a strength of the study, more frequent assessment of affect (for example using ecological momentary assessment Reference Ebner-Priemer, Eid, Kleindienst, Stabenow and Trull38,Reference Jahng, Wood and Trull51 ) may have been able to capture more frequent fluctuations in affect than we could assess in the present study. Second, these results may not be fully generalisable to the full study sample given that the present sample was more likely to be taking lithium, less likely to be taking a mood stabiliser, less likely to have an anxiety disorder and completed more assessments. Although we do not know why some patients did not continue with treatment, it is possible that their anxiety disorders interfered with their willingness to attend treatment sessions. Third, the sample also was quite morbid, with over half of the sample having experienced more than 10 episodes of depression and/or mania; thus, implications for individuals with better illness history is not clear. Fourth, recovery from depression was defined by the same measure used to compute instability. However, whereas recovery was defined as low absolute levels of symptoms, instability was computed as visit-to-visit fluctuations in symptoms; indeed, instability predicted depression course beyond the impact of absolute symptom levels, suggesting that the instability of mood symptoms may carry additional importance in contributing to the course of bipolar depression. Nevertheless, the possibility of shared method variance between instability and recovery must be noted.

Future directions

In conclusion, although this area of enquiry is relatively new in bipolar disorder, the results of the current study suggest that affective instability may be a clinically relevant and important characteristic that influences the course of bipolar depression. Future work should consider personality comorbidities, the mechanisms by which affective instability contributes to poorer course of illness, and whether psychosocial or pharmacological treatments can attenuate affective instability over time, thereby reducing the burden of depression in bipolar disorder.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.