Social isolation, a multi-dimensional experience characterized by few meaningful social connections and contacts (Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012; Smith & Victor, Reference Smith and Victor2018), remains at the forefront of concerns over the well-being of older people 60 years of age and older. Consequently, hundreds of interventions have been developed and implemented to reconnect those who are isolated from the social world (Dickens, Richards, Greaves, & Campbell, Reference Dickens, Richards, Greaves and Campbell2011). There remains, however, a significant gap in the literature on social isolation interventions regarding best practices, and there is a great deal of disagreement within the literature regarding how it should be identified, prevented, and addressed (Cattan, White, Bond, & Learmouth, Reference Cattan, White, Bond and Learmouth2005; Findlay, Reference Findlay2003). Recent developments in the field have brought about great interest in particular aspects of interventions including social prescribing, assistive technology, and intergenerational components, with studies identifying mixed success with forms of each of these (Poscia et al., Reference Poscia, Stojanovic, La Milia, Duplaga, Grysztar and Moscato2018). Friendly visiting programs, often referred to as befriending schemes, have been a mainstay in the world of isolation and loneliness interventions, and are widely implemented across geographical regions, contexts, and settings. They have also been used to combat loneliness (Siette, Cassidy, & Priebe, Reference Siette, Cassidy and Priebe2017), a subjective feeling of having insufficient social connection (de Jong Gierveld & Keating, Reference de Jong Gierveld and Keating2015). Although many program developers and researchers alike agree that friendly visiting programs hold great potential to improve the lives of socially isolated older people, few research studies have been able to determine why and how these types of programs may be so successful (Andrews, Gavin, Begley, & Brodie, Reference Andrews, Gavin, Begley and Brodie2003). Given the various links between social isolation and all-cause mortality (Steptoe, Shankar, Demakakos, & Wardle, Reference Steptoe, Shankar, Demakakos and Wardle2013), improved intervention efforts are needed to connect with isolated and at-risk older people and mitigate harmful effects when possible.

This study contributes to the existing body of literature on friendly visiting programs by conducting a realist evaluation of friendly visiting programs addressing social isolation in order to determine what works, for whom, and under what conditions. Unlike other review methods (e.g., systematic reviews) that primarily focus on whether or not a given intervention is successful, realist syntheses are concerned with identifying the mechanisms and contextual factors underlying successful and unsuccessful interventions in order to better understand why and how an intervention may be successful or not, and with which populations (Pawson, Reference Pawson2002). By deconstructing a sample of friendly visiting programs intended to reconnect older people who are isolated or at risk, this study investigates the central program components that enable success within this type of intervention. The hope is that realist insights can be applied to the refinement of existing friendly visiting programs and the development of new ones in a variety of contexts.

The present article outlines relevant background knowledge concerning social isolation in later life, in addition to the state of the evidence related to friendly visiting programs and isolation interventions more broadly. The realist review method is then outlined. The results of the realist review analysis are summarized in the form of mechanisms and contextual factors that appear to lead to the success of friendly visiting programs. Lastly, these mechanisms and contextual factors are used to sketch a working diagram of a friendly visiting program theory that can be taken up and revised as additional evidence comes to light as well as used in the refinement and development of programs.

Background

Growing numbers of older people worldwide are experiencing social isolation – a harmful social state characterized by few to no reliable social contacts and little social support (Hortulanus, Machielse, & Meeuwesen, Reference Hortulanus, Machielse and Meeuwesen2006; Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012). However, it is not possible to determine precisely how many people may be isolated at one time because of the very nature of the problem; specifically, that socially isolated older people are typically hard to find and hard to reach and are often considered to be “hidden” (Chan, Yu, & Choi, Reference Chan, Yu and Choi2017; Portacolone, Perissinotto, Yeh, & Greysen, Reference Portacolone, Perissinotto, Yeh and Greysen2018). Those who are experiencing isolation and exclusion are likely to have fewer relationships and community connections to link them with programs of support, resources, and other amenities. Studies in the Anglo-American world estimate that as many as 30 per cent of older adults may be at risk of isolation. In Canada, estimates of older adults at risk of social isolation vary between 12 and 30 per cent (Gilmour & Ramage-Morin, Reference Gilmour and Ramage-Morin2020; Keefe, Andrew, Fancey, & Hall, Reference Keefe, Andrew, Fancey and Hall2006); compared with 17 per cent in the United States (Ortiz, Reference Ortiz2011); and 20 per cent in the United Kingdom (Victor, Scambler, Bond, & Bowling, Reference Victor, Scambler, Bond and Bowling2000). Elsewhere, the World Health Organization has stated that there are currently no estimates of social isolation prevalence on a global scale because of significant differences in how isolation is measured and defined (World Health Organization, 2021).

Aside from challenges with identifying and connecting with socially isolated older people, other measurement issues exist. Notably, social isolation has commonly been conflated with loneliness, a negative and subjective feeling stemming from a discrepancy between desired quality and/or quantity of social engagement and actual quality and/or quantity of social engagement (Machielse, Reference Machielse2015). Prevalence of social isolation and loneliness are often reported together (see World Health Organization, 2021). Although closely related, experts tend to distinguish experiences of loneliness from social isolation, which tends to be conceptualized as a multi-dimensional and at least partially objective social circumstance characterized by few social connections, low social support, and low social engagement (Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012). These experiences often overlap (Machielse, Reference Machielse2015; Smith & Victor, Reference Smith and Victor2018), and can be detrimental to overall well-being (Courtin & Knapp, Reference Courtin and Knapp2017). Longitudinal data suggest that social isolation is more closely associated with risk of mortality (Steptoe et al., Reference Steptoe, Shankar, Demakakos and Wardle2013), although studies have also shown that loneliness in later life predicts several considerable aspects of morbidity (Ong, Uchino, & Wethington, Reference Ong, Uchino and Wethington2016). Additionally, older people who are socially isolated may experience a greater risk of loneliness as a result (Djernes, Reference Djernes2006), contributing to concurrent experiences of the two. Preventing and remedying social isolation therefore becomes increasingly critical as it may – for many – prevent or reduce loneliness as well.

Despite challenges with measurement, it is likely that the overall prevalence of social isolation in later life has likely increased throughout the COVID-19 global pandemic (Holt-Lunstad, Reference Holt-Lunstad2021). This is a troubling possibility, especially given that experiencing social isolation in later life has been linked to numerous negative health and social effects including cardiovascular disease, depression, and cognitive impairment (Alspach, Reference Alspach2013; Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012; Shankar, McMunn, Banks, & Steptoe, Reference Shankar, McMunn, Banks and Steptoe2011), and has been identified as a significant predictor of mortality in older people (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, Reference Holt-Lunstad, Smith and Layton2010). As a result of recent estimates on the prevalence of social isolation and a growing body of literature on its consequences to health and well-being, several countries including Canada and the United Kingdom have identified the prevention and/or reduction of social isolation as a policy priority (Cattan, Kime, & Bagnall, Reference Cattan, Kime and Bagnall2011; Weldrick & Grenier, Reference Weldrick and Grenier2018).

To ameliorate the problem and increase connection among isolated seniors, many group interventions have been developed and implemented in a wide array of contexts. These interventions have come in many forms with varying degrees of success over recent decades. Many interventions have incorporated various forms of information technology (e.g., computers, tablets) (Bradley & Poppen, Reference Bradley and Poppen2003; Breck, Dennis, & Leedahl, Reference Breck, Dennis and Leedahl2018) with the hope of encouraging online or telephone communication. Otherwise, intergenerational engagement programs have been developed with the intent of building up the social networks of isolated older people by connecting them with younger people in various settings, such as in technology training programs and choirs (Harris & Caporella, Reference Harris and Caporella2014; Lee & Kim, Reference Lee and Kim2019). Other group-based programs have come in the form of community arts programs (Teater & Baldwin, Reference Teater and Baldwin2014), museum-based programs (Thomson, Lockyer, Camic, & Chatterjee, Reference Thomson, Lockyer, Camic and Chatterjee2018), and physical activity programs (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Yu and Choi2017).

In other settings, program developers and community service agencies have instead opted for one-to-one based programs. These programs have included interventions such as gatekeeping/referral programs (Bartsch, Rodgers, & Strong, Reference Bartsch, Rodgers and Strong2013) and virtual learning programs (Botner, Reference Botner2018) amongst other designs. To date, both group-based and one-to-one interventions have had mixed results, with some studies reporting successful reduction in social isolation, and others reporting no such change (Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, White, Bond and Learmouth2005). To muddy the waters further, systematic reviews and meta-analyses have also reported conflicting findings. For example, one review found that one-to-one-based programs have more commonly shown significant effects on isolation (Poscia et al., Reference Poscia, Stojanovic, La Milia, Duplaga, Grysztar and Moscato2018), whereas others have reported that group-based programs tend to be more successful (Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, White, Bond and Learmouth2005; Dickens et al., Reference Dickens, Richards, Greaves and Campbell2011). With respect to other defining features, a systematic review by Hawton et al. (Reference Hawton, Green, Dickens, Richards, Taylor and Edwards2011) found that interventions with an explicitly articulated theoretical basis were more likely to result in successful outcomes. On the other hand, they also found that interventions were less likely to be successful if they exclusively targeted socially isolated older people as opposed to opening up the intervention to all older people regardless of isolation (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Green, Dickens, Richards, Taylor and Edwards2011). Ultimately, no single isolation intervention has garnered enough evidence to be considered more effective than all others.

Overall, many questions remain regarding social isolation interventions and how they might be successful for older people including what works, for whom, how, and under what conditions. For example, age ranges and inclusion criteria for program participants often range between ≥ 50 and ≥ 65 years of age, depending on who is administering the intervention, and in what type of setting. Likewise, many differences exist across participant demographics (e.g., functional status, residential status, co-morbidities) contingent on either the organizational mandates of the host organization and/or the research questions of the program evaluators. Indeed, further research and refined evaluations are needed to draw meaningful conclusions for future program development (Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, White, Bond and Learmouth2005; Dickens et al., Reference Dickens, Richards, Greaves and Campbell2011; Findlay, Reference Findlay2003) to determine the relative benefits of both one-to-one and group-based interventions for different sub-groups of older people. These could include those recently widowed, individuals belonging to specific religious or cultural groups, those with particular physical conditions or mental illnesses, or those of particular age ranges, among others. (Kobayashi, Cloutier-Fisher, & Roth, Reference Kobayashi, Cloutier-Fisher and Roth2009).

One model of one-to-one social isolation intervention which has been implemented across many contexts and locations is the friendly visiting model. In a typical friendly visiting program, socially isolated older people are visited in their homes by volunteers. These volunteers are usually facilitated by a host organization, such as a non-profit group, seniors’ service agency, or other community group. Many programs that fit into this category involve weekly or biweekly visits by the volunteer and operate under the assumption that the volunteer may be able to become a friend or confidante, thereby filling a void in the isolated client’s social network or assisting in development of new social connections (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Gavin, Begley and Brodie2003; Calsyn, Munson, Peaco, Kupferberg, & Jackson, Reference Calsyn, Munson, Peaco, Kupferberg and Jackson1984; Korte & Gupta, Reference Korte and Gupta1991). Although these programs have been implemented across many countries over the past several decades, there remains a dearth of knowledge with respect to how, when, and why these programs may successfully reduce social isolation in later life. Early studies purported that friendly visiting programs had not been sufficiently evaluated (Bogat & Jason, Reference Bogat and Jason1983), and that many studies were too flawed methodologically to draw credible conclusions (Calsyn et al., Reference Calsyn, Munson, Peaco, Kupferberg and Jackson1984). Others have stated an explicit need for studies of friendly visiting programs in non-Western contexts (Cheung & Ngan, Reference Cheung and Ngan2000), and scholars have begun to address this need in recent years (see Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Gavin, Begley and Brodie2003; Wiles et al., Reference Wiles, Morgan, Moeke-Maxwell, Black, Park and Dewes2019).

Additional evidence of underlying mechanisms and important contextual factors is needed to support the development of effective friendly visiting programs, especially given the immense potential that they hold. Unlike many other types of isolation interventions, friendly visiting schemes can be easily modified to meet the needs of the individual clients. For example, they may be structured or unstructured, and can involve intergenerational components (Calsyn et al., Reference Calsyn, Munson, Peaco, Kupferberg and Jackson1984). They can be made available to both community-dwelling older people and those living in long-term care or nursing institutions (Damianakis, Wagner, Bernstein, & Marziali, Reference Damianakis, Wagner, Bernstein and Marziali2007), who may experience different risk factors to those living alone in the community (Boamah, Weldrick, Lee, & Taylor, Reference Boamah, Weldrick, Lee and Taylor2021). Friendly visiting programs are also widely considered to be cost effective and may even be conducted over the phone when in-person visiting is not possible (Calsyn et al., Reference Calsyn, Munson, Peaco, Kupferberg and Jackson1984; Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, Kime and Bagnall2011), meaning that friendly visits can be successfully implemented in rural and/or remote areas where other forms of engagement may be less accessible. Because friendly visiting programs already exist across many settings and locations, existing programs could, in theory, adjust operations according to emerging evidence in order to better serve participants. In other words, research on friendly visiting programs has the potential to create a sizable impact because of the widespread popularity of this type of approach.

In this article, we seek to better understand the potential of friendly visiting interventions for reducing social isolation using a realist synthesis, a method of knowledge synthesis. Realist syntheses are somewhat unique in that they are concerned with theory development and refinement (Rycroft-Malone et al., Reference Rycroft-Malone, McCormack, Hutchinson, DeCorby, Bucknall and Kent2012). Unlike systematic reviews, they are not concerned with whether or not a given intervention works, but rather how it works, for whom it works, and under what circumstances (Pawson, Reference Pawson2002; Wong, Greenhalgh, Westhorp, Buckingham, & Pawson, Reference Wong, Greenhalgh, Westhorp, Buckingham and Pawson2013). Importantly, realist reviews are underpinned by a realist philosophy of science (Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Chilton, Wyatt, Abraham, Ford and Woods2015). Realist reviews take the perspective that programs/interventions and policies are theories and recognize that theories only work within certain contexts. It is not programs that “work” but rather the mechanisms that lead to change, and these mechanisms are only “triggered” within certain circumstances (i.e., contexts).

The realist synthesis methodology is considered by many to be especially helpful for reviewing and synthesizing knowledge from complex social interventions (Rycroft-Malone et al., Reference Rycroft-Malone, McCormack, Hutchinson, DeCorby, Bucknall and Kent2012; Wong, Greenhalgh, & Pawson, Reference Wong, Greenhalgh and Pawson2010). Typically, complex interventions exist within open systems (i.e., not controlled experimental settings or limited in their components), and have varying degrees of success depending on the context, but rely on mechanisms which may “misfire” at any point (Pawson, Reference Pawson2002, p. 342). According to this definition, all social isolation interventions would fit in the category of “complex intervention”. In fact, recent work has called for a realist review to investigate social isolation and loneliness interventions among older people because of the complex nature of such interventions and the need to more clearly conceptualize how and why such interventions may bring about successful outcomes (Fakoya, McCorry, & Donnelly, Reference Fakoya, McCorry and Donnelly2020). The present review seeks to answer this call by conducting a realist synthesis of friendly visiting programs for socially isolated older people. The overall purpose of this synthesis is to take steps towards filling several gaps in the social isolation literature while simultaneously identifying how friendly visiting programs work, for whom, and in what circumstances. As noted, this synthesis will provide the foundation for a friendly visiting program theory.

Methods

This realist synthesis followed the iterative seven-step process outlined by Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey, and Walshe (Reference Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey and Walshe2005) and is reported in accordance with Realist And MEta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) publication standards for realist reviews (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Greenhalgh, Westhorp, Buckingham and Pawson2013). The first step involves clarifying the focus and scope of the study, including the research questions. The second step entails searching for relevant evidence to address the scope and research question. This is a crucial step in the process and differs significantly from the literature searching process in other types of reviews (e.g., systematic reviews) in that it is non-linear and often continues concurrently with later steps (Pawson, Reference Pawson2002; Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey, & Walshe, Reference Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey and Walshe2004). The third step involves appraising studies for relevance and rigour to determine which pieces of evidence are to be included in the review. Notably, steps four and five consist of extracting and synthesizing evidence from studies deemed relevant in order to identify potential program theories and mechanisms. Finally, steps six and seven involve drawing conclusions, making recommendations, and disseminating those recommendations with the ultimate goal of eventually influencing the development of new interventions and/or refinement of existing interventions (Pawson et al., Reference Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey and Walshe2004). These steps are discussed in greater detail in the following sections.

Clarifying the Scope of the Review

In order to address the topic at hand, the following research questions were used to guide the realist review: (1) How are friendly visiting programs successful (e.g., in terms of the strength of their theoretical foundations)? (2) For whom are friendly visiting interventions effective (e.g., demographics, sub-groups of older people)? and (3) Under what conditions are friendly visiting interventions successful (e.g., program design, context, location)? By synthesizing evidence regarding these three questions, this review aims to uncover efficacious program design features and target population characteristics that can be used to inform the development and/or refinement of friendly visiting interventions.

For this review, interventions or programs were deemed “successful” based on their reported outcomes. Definitions of “success” varied quite significantly depending on the study design, population, outcome measures, and other contextual factors. For example, one study measured life satisfaction as a primary outcome measure (Calsyn et al., Reference Calsyn, Munson, Peaco, Kupferberg and Jackson1984), whereas another study used qualitative interviews and a combination of standardized scales measuring isolation, loneliness, and life satisfaction to determine the impact of the program (Roberts & Windle, Reference Roberts and Windle2020). This is to be expected, as realist reviews compile a wide variety of evaluation and study designs. As methodologies differed across studies, so too did the accompanying evidence. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies are included in the sample, meaning that not all evidence came in the form of validated scales or from interviews/narratives.

Search for Relevant Evidence

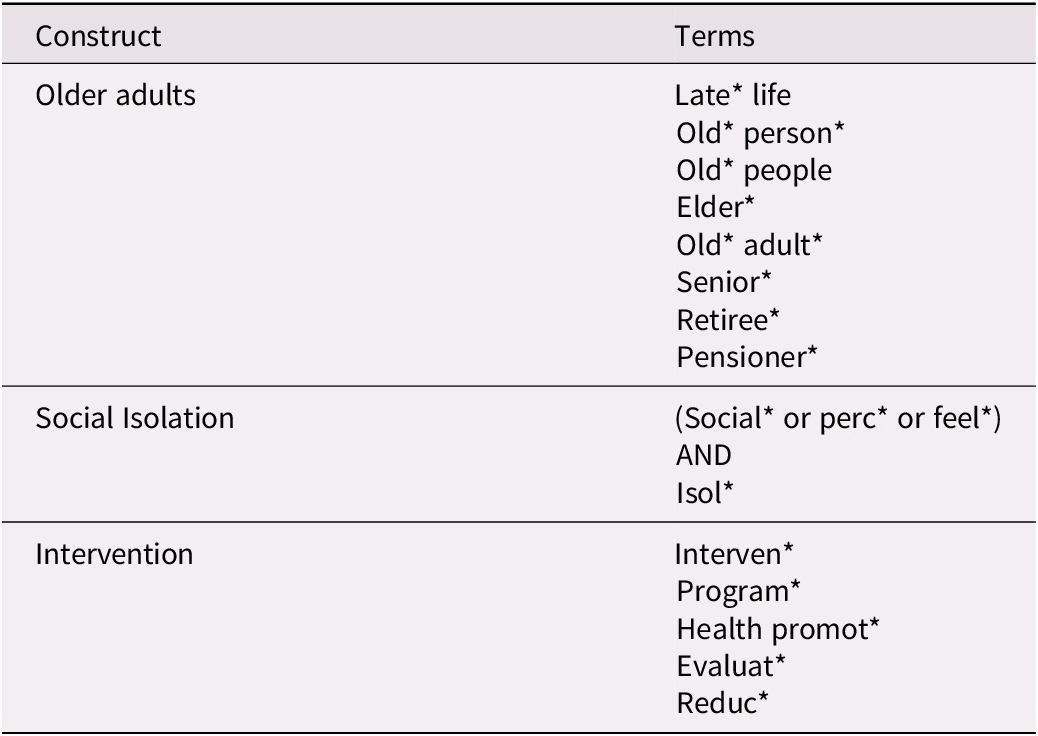

Initial searching was conducted in Web of Science using several combinations of relevant keywords. We read several published studies of friendly visiting interventions and hand searched reference lists to elucidate how these studies are typically described and named in the scholarly literature. Using these preliminary insights, a comprehensive search strategy was developed and used to conduct a search for relevant intervention studies. Six search engines and databases were searched, including: AgeLine, Social Work Abstracts, Social Science Abstracts, MEDLINE®, PsycInfo, and Web of Science. Search terms differed slightly across the databases as there are differences in how articles are indexed, and under what terms, but all searches included a combination of terms relating to older people, social isolation, and interventions. Examples of relevant search terms are included in Table 1. No data parameters were set on the search. The final search took place in December 2021.

Table 1. Example of search terms used

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

R.W. reviewed the studies to determine their inclusion eligibility. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria:

-

1. The study pertains to older people (as defined in the study). No specific age range was specified in the search strategy.

-

2. The program is intended to reduce or alleviate social isolation. Studies that were explicitly intended to reduce loneliness (as opposed to social isolation) were not included as per the review objectives.

-

3. The study included/reported some form of outcome measure(s).

-

4. The program involved friendly visiting and/or befriending.

-

5. The study was published in English.

Study Appraisal

When the final search of the literature had been conducted and initial screening was complete, relevant full texts were appraised. Once again, this process differs from the process of quality appraisal in other types of reviews that may utilize a “hierarchy” of evidence. In realist reviews, studies are judged based on relevance and rigour (Pawson et al., Reference Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey and Walshe2004). In terms of relevance, studies are judged on whether they address a particular program theory (i.e., via some type of friendly visiting scheme), not whether they address a particular topic (i.e., some other type of intervention that does not relate to friendly visiting). This is a critical distinction, as other social isolation interventions (e.g., social prescription, computer learning programs) likely function as a result of unique mechanisms and contexts. With regard to rigour, studies are judged on whether the inference(s) made by the original researchers can carry enough weight “to make a methodologically credible contribution” (Pawson et al., Reference Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey and Walshe2005, p. 30). This process is not used to determine whether a given study is methodologically flawless, but rather whether the study is appropriate for inclusion in a particular review. In other words, the reviewer assesses a study based on “fitness for purpose” (Pawson et al., Reference Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey and Walshe2005). In doing so, the reviewer ensures that only relevant intervention studies that speak to the review at hand are included. These two appraisal criteria guide the process of determining which evidence is analyzed.

Seven studies were included in the final analysis following the study appraisal phase and hand searching (Figure 1). Hand searching included manually searching reference lists of relevant scholarly papers and grey literature publications. Grey literature publications were eligible for inclusion, but none met all inclusion criteria. It should also be noted that many of the full texts that were excluded were removed for lack of detail on program components or execution. This obstacle is unpacked later in the article.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

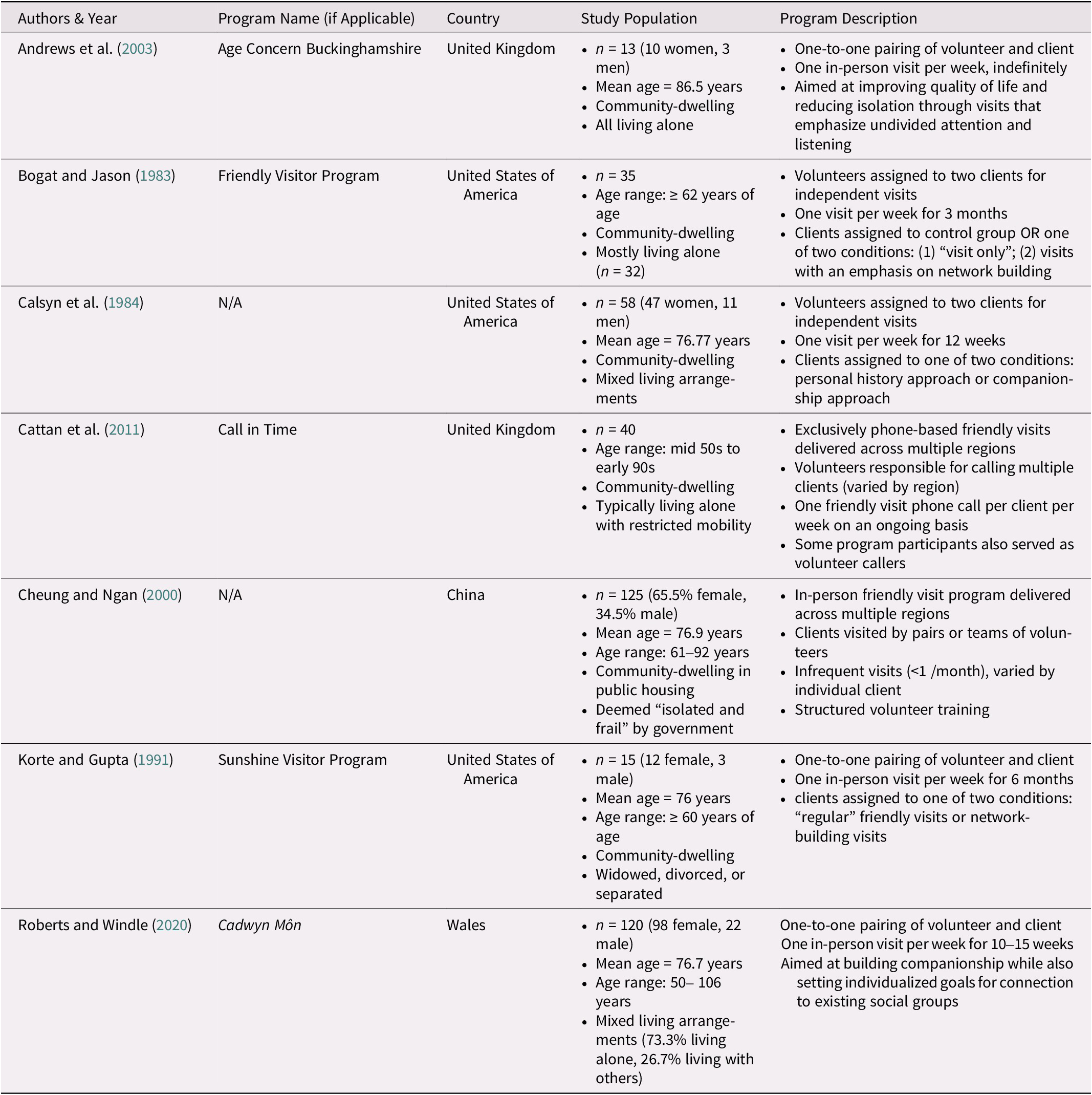

Data Extraction

Basic descriptive information was initially extracted from all studies, including authors and year, program name, location, study population, and program description. This information is summarized in Table 2. The next phase of data extraction involved scanning articles/reports for demi-regularities. In realist syntheses, demi-regularities are prominent themes and/or “patterns of outcomes” (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Greenhalgh, Westhorp, Buckingham and Pawson2013, p. 10). The goal of the realist review is not to explain every aspect of the moving parts and interacting contexts within an intervention, but rather to identify these patterns and gain insights into the inner workings of a given family of interventions. For this first phase of the analysis, key information was not always taken from the actual results of a given program or intervention, but rather from their respective methods and discussion sections. Key descriptive information regarding program implementation (e.g., how volunteers were trained, how clients were recruited), barriers to success (e.g., challenges experienced by the host agency), facilitators of success (e.g., insights from clients on what elements were effective), and authors’ reflections on the process of performing the intervention or implementing the program tended to occur within the Methods and Discussion sections of most reports, rather than in the Results sections of the articles included. This strategy of sifting helpful bits of knowledge from descriptive information is a tactic used by many scholars who conduct realist syntheses and is a distinguishing feature of this type of review (Greenhalgh, Macfarlane, Steed, & Walton, Reference Greenhalgh, Macfarlane, Steed and Walton2016; Pawson, Reference Pawson2002).

Table 2. Brief overview of friendly visiting programs included in analysis

Data Synthesis and Analysis

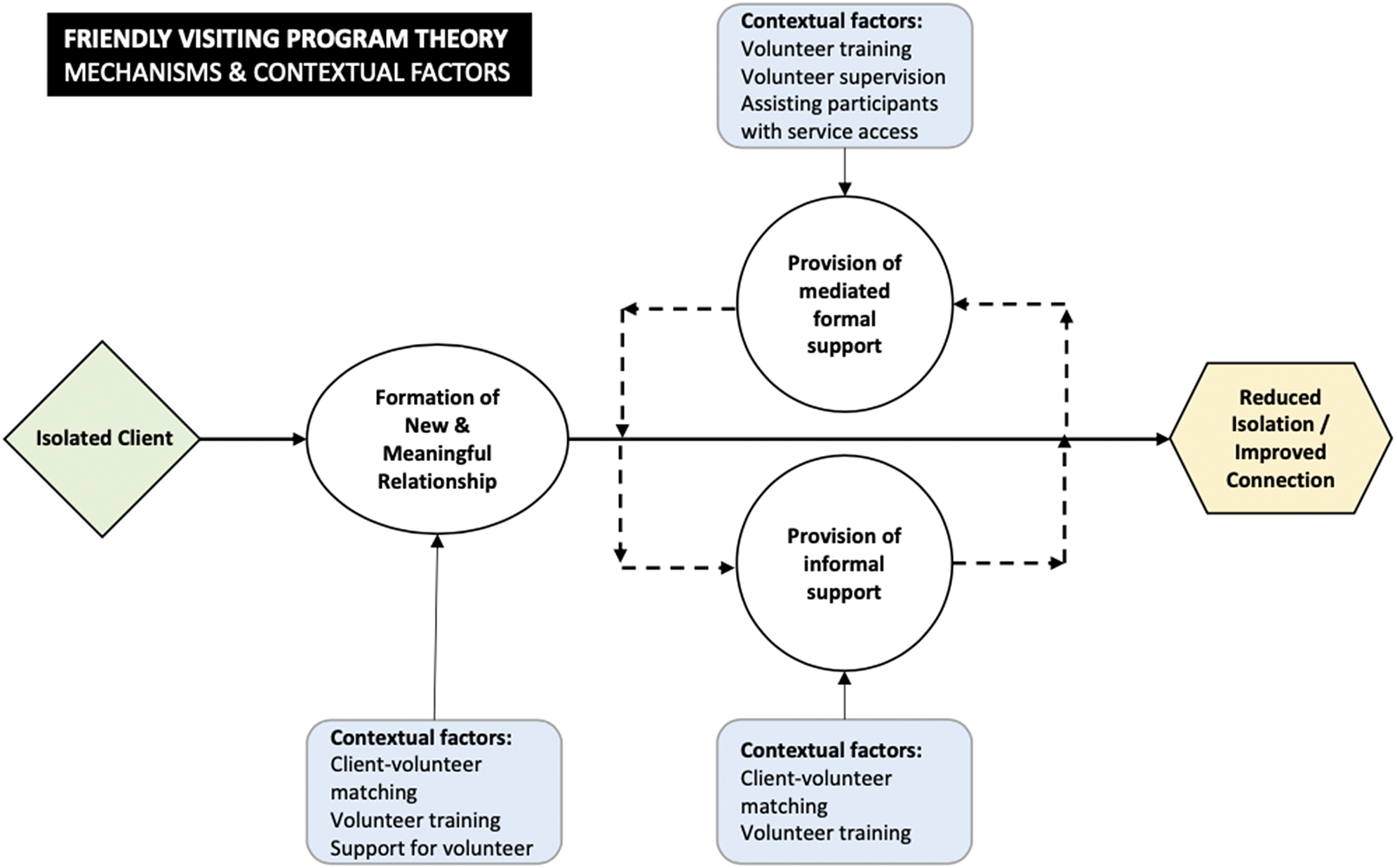

Information extracted from programs was compiled during the data synthesis phase, although data extraction and data synthesis are often concurrent. In many cases, data extraction happens iteratively, as one study will shed light on a program characteristic (e.g., volunteer training) that might shed light on possible mechanisms that lead to program success. In this study, the reviewer moved between the extraction and synthesis phases iteratively identifying new information that may not have appeared relevant in the initial extraction. The process of data synthesis and analysis involved piecing together demi-regularities with the intent of forming a coherent theory of how they may fit together and function. The goal of data synthesis is to develop a middle-range theory about how (i.e., through what mechanism[s]) friendly visiting programs have the potential to reduce social isolation among older people. Several preliminary arrangements of the program theory were constructed and revised as additional data were compiled. The final program theory is presented in Figure 2. This program theory is not a rigid understanding of how friendly visiting works, but rather a theory that can be tested, re-tested, and refined through further research and program development.

Figure 2. Friendly visiting program theory.

Recommendations and Dissemination

The final two steps in this realist review involved making recommendations and disseminating findings with the intention of influencing policy and/or existing interventions (Pawson et al., Reference Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey and Walshe2004). Within the context of this article, observations and recommendations for future research and program development are provided in the Discussion section according to the proposed program theory.

Results

Included Studies

Seven studies were included in the final analysis. A brief overview of the included studies is provided in Table 2.

Research Question 1: How are friendly visiting programs successful?

The first demi-regularity (n = 3) identified in the sample of studies pertaining to how friendly visiting programs may function successfully was related to reciprocity between clients and volunteers. This reciprocal, two-way dynamic was described in several studies as being a meaningful and important characteristic of the newly formed relationship. For example, Andrews et al. (Reference Andrews, Gavin, Begley and Brodie2003) stated that “reciprocity in the befriending relationship was regarded by clients as important and they needed to feel that both they themselves and their befrienders were getting ‘something’ out of the relationship” (p. 358). Additionally, Cattan et al. (Reference Cattan, Kime and Bagnall2011) reported that participants in the Call in Time program experienced benefits stemming from the fact that their relationship with the volunteer was not one-sided. Participants articulated that the befriending program enabled them to engage in friendly, two-way conversations about everyday life, whereas “doctors or social workers dealt with problems” (Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, Kime and Bagnall2011, p. 203).

Other program evaluations, including the one reported by Calsyn et al. (Reference Calsyn, Munson, Peaco, Kupferberg and Jackson1984), also found reciprocity to be a key factor in the success of the client–volunteer relationship. The authors of this study report the findings of two experimental conditions: one “traditional” friendly visiting program, and one that involved a personal history component. Reciprocity was identified as a key determinant of success in both conditions. Calsyn and co-authors (Reference Calsyn, Munson, Peaco, Kupferberg and Jackson1984) stated quite plainly that from their perspective “clients in both conditions had more positive outcomes the more reciprocal the relationship was between client and visitor” (p. 38), and that some clients went out of their way to reciprocate by giving their volunteers a homemade pie or other token of appreciation. In this regard, truly reciprocal relationships between clients and volunteers may mirror the benefits gained through existing friendships and relationships outside of arranged programs. The development of a meaningful and reciprocal friendship between the volunteer and client may set friendly visiting programs apart from other forms of arranged and/or formal social support.

The second demi-regularity identified pertaining to how friendly visiting programs may successfully improve the social well-being of isolated older people was connected to knowledge of local services and amenities. Several studies (n = 3) described an improvement in clients’ knowledge of services and programs accessible to them in their respective communities over the course of their involvement with the friendly visiting program. For example, Roberts and Windle (Reference Roberts and Windle2020) stated that the participants in their program “were often not aware of groups and clubs in their communities, and the majority report having joined groups or classes during their time with the volunteer” (p. 159). Likewise, Cheung and Ngan (Reference Cheung and Ngan2000) intentionally measured “knowledge of services” as an outcome measure and found that participants in the program reported a significantly greater knowledge of community services and amenities 6 months after completing the initial survey.

Research Question 2: For whom are friendly visiting interventions effective?

The gender distribution of sample interventions arose as the most noteworthy demi-regularity related to the second research question. Most studies in the sample described a mix of both male and female participants but tended to have a greater proportion of female participants (n = 5). These proportions ranged quite significantly. For example, Cheung and Ngan (Reference Cheung and Ngan2000) reported that 65 per cent of their participants were women, whereas Korte and Gupta (Reference Korte and Gupta1991) reported that 80 per cent of their participants were women. Likewise, Andrews et al. (Reference Andrews, Gavin, Begley and Brodie2003) reported that all but three of the participants interviewed were women, which was representative of the 150 service users enrolled in the befriending program. Other programs, including the Call in Time program (Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, Kime and Bagnall2011) and the Friendly Visitor Program (Bogat & Jason, Reference Bogat and Jason1983) did not provide gender distributions. The presence of a female-skewed gender distribution is both expected, and yet illuminating with respect to the success of the friendly visiting programs. As a demi-regularity, this finding suggests that friendly visiting programs have a real potential to improve social connection among older women in particular, given the success of the programs included.

The second demi-regularity revealed in the analysis pertaining to participant characteristics related to “homebound” or “housebound” participants. Three studies described participants as being housebound, meaning that they were largely confined to their homes with limited time spent out in the community or beyond. Cattan and co-authors (Reference Cattan, Kime and Bagnall2011) stated that participants in the Call in Time program “were often housebound, had restricted mobility, lived alone and were reliant on external agencies for their health and social care needs” (p. 200). Similarly, Cheung and Ngan (Reference Cheung and Ngan2000) describe a process through which a government department prioritized vulnerable older people living in public housing for participation in the friendly visiting program. Based on the prioritization factors, older people with significant mobility concerns and/or those who were bedridden were enrolled prior to those without such concerns (Cheung & Ngan, Reference Cheung and Ngan2000). This finding is promising and suggests that friendly visiting programs have the potential to improve the social lives of isolated and/or at-risk and homebound older people, who may be especially susceptible to experiencing long-term isolation.

Research Question 3: Under what conditions are friendly visiting interventions successful?

The most significant demi-regularity addressing this research question was client and volunteer matching within the friendly visiting programs. Most studies (n = 5) clearly articulated the importance of appropriately matching clients and visitors in order to encourage the formation of a strong and supportive relationship. For example, Roberts and Windle (Reference Roberts and Windle2020) states that one of the keys to the success of the Cadwyn Môn program was the care taken in putting together compatible client–volunteer matches. They go on to write that the interviews with clients reflected the importance of the matches. Likewise, Andrews and co-authors identified in their qualitative interview data that “good matching appeared to be a prerequisite for the development of an enduring relationship” (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Gavin, Begley and Brodie2003, p. 356). In terms of program conditions, it appears that forming compatible matches is a cornerstone of success in friendly visiting interventions.

The demi-regularity of client and volunteer matching is a helpful finding that may serve to guide program development in the future, and yet it is not clear how exactly good matches may be formed, and what characteristics may be most beneficial to use as the foundation for the matching. Korte and Gupta (Reference Korte and Gupta1991) described a process of volunteer and client matching in order to meet the needs of both parties. They stated that matches were determined “with consideration given to the perceived compatibility between the two individuals (e.g., gender, personality, background) and any personal requests that either party had made” (Korte & Gupta, Reference Korte and Gupta1991, p. 406). They also stated that matches were “cleared” with both the volunteer and the client prior to the first visit. It is not clear what this entailed, but the presumed goal was to assure that both parties were satisfied with the pairing. Calsyn et al. (Reference Calsyn, Munson, Peaco, Kupferberg and Jackson1984) also reported attempts “to match clients and visitors on the basis of expressed interest and other preferences as well as demographic characteristics” (p. 39), but reported that they did not have a systematic method for doing so. Overall, it became clear that host organizations could encourage the success of the friendly visiting program by forming compatible matches, but it remains unclear what criteria may be best used for this purpose.

Another notable demi-regularity that became apparent among the included studies was the role of volunteer training in the success of the friendly visiting programs. Most programs in the sample (n = 4) included a description of training provided to the volunteers involved with the program. Although training content varied across programs, most included some form of communication skills training, and education on local services and amenities for older people. Cheung and Ngan (Reference Cheung and Ngan2000) emphasized the significance of thorough volunteer training, and described the training process as including eight distinct topics such as communication skills and knowledge of local services for older people. Calsyn et al. (Reference Calsyn, Munson, Peaco, Kupferberg and Jackson1984) report that in their study, volunteers were trained during three 4-hour sessions that included topics such as aging, death, communication skills, and active listening, among others. By training volunteers, host organizations can extend their influence and support to the isolated individual through the volunteer. In this way, volunteers can perhaps be seen as paraprofessionals delivering indirect or mediated formal support to the isolated clients.

In some cases, the volunteer training was quite thorough. Korte and Gupta (Reference Korte and Gupta1991) specified that volunteers in both their regular friendly visiting and their “network building” conditions received several hours of training. Volunteers in the friendly visiting condition received 4 hours of training, whereas the volunteers in the network building condition received 8 hours. Both groups of volunteers received 4 hours of training on aging, skills needed for friendly visiting, and community services for older people. The volunteers in the network building condition then received an additional 4 hours of training on specific aspects of social networks and network deficiencies that they would be attempting to improve upon during their time as visitors (Korte & Gupta, Reference Korte and Gupta1991). It is not clear whether the additional 4 hours of training for the volunteers in the network building condition led to any additional benefits. However, this is a distinction that could be further explored in future programs and reviews.

The final demi-regularity identified pertaining to program conditions relates to ongoing support for volunteers throughout the duration of the friendly visiting program. Four studies in the sample included a description of some form of ongoing volunteer support provided by host organizations. This support varied across programs but appears to be an important contextual factor in shaping the success of these befriending programs. For example, Bogat and Jason stated that volunteers in the Friendly Visitor Program participated in weekly supervision sessions with the host organization in order to “generate resources, strategies, and support” for the volunteers to pass on to their respective clients (Bogat and Jason, Reference Bogat and Jason1983, p. 271). Not only did these supervision sessions ensure that volunteers felt equipped to support their isolated client, they also enabled the organization to indirectly provide additional individualized support to the clients.

Calsyn and co-authors (Reference Calsyn, Munson, Peaco, Kupferberg and Jackson1984) provided a helpful and detailed look into the supervision process within their program. Supervision meetings, which included between six and eight volunteers and one of the authors, provided opportunity for the volunteers to discuss each of their clients individually. Through this process, volunteers and organizers would provide “suggestions regarding activities to do on the visit and/or agencies which might provide needed services” (Calsyn et al., Reference Calsyn, Munson, Peaco, Kupferberg and Jackson1984, p. 34). Once again, this type of supervision was a means through which the program organizers may have been able to influence the success of the program. Without some form of supervision and/or check-in procedure volunteers may be left to rely upon their existing knowledge and skills in order to improve the social well-being of their paired client. Future friendly visiting programs, and indeed other social programs that rely upon volunteers, are encouraged to build in ongoing supervision or support where feasible.

Mechanisms

Based on the analysis of demi-regularities presented, we identified three main mechanisms through which friendly visiting programs/befriending schemes appear to achieve the goal of reducing social isolation (see Figure 2).

Mechanism 1: Formation of a new and meaningful relationship

Most studies in the sample described the formation of a new relationship between client and volunteer visitor and emphasized the importance of this relationship being as much like a “real” friendship as possible within the confines of an arranged friendly visiting scheme. Based on the evidence, it seems likely that socially isolated older people are more likely to experience positive results from a friendly visiting program if they can form a new and meaningful friendship with the volunteer. Reciprocity, reliability, and authenticity were all key elements in successful formation of client–volunteer relationships across the programs included. Together these findings suggest that clients may experience social benefits from friendly visiting that they may not experience in other types of relationships with service providers or health professionals.

Our sample of studies identified several vital contextual factors that influence that successful triggering of this mechanism. The most critical contextual factor appears to be thoughtful matching of clients and volunteer visitors. The programs included in our sample provided varying degrees of detail pertaining to how matches were determined, although most studies explicitly stated that matching was an important determinant of program success. Likewise, volunteer training in many programs involved some aspect of communication and/or active listening skills training. This training appears to have greatly supported the development of authentic relationships between volunteers and isolated clients. In some cases, the ongoing support of volunteers, such as through supervision and/or check-in meetings, may have also provided volunteers with helpful feedback regarding their new relationship with the client. These contextual factors facilitate the building of a supportive relationship with a new social contact, previously unknown to the isolated client. When this newly formed relationship feels authentic, the isolated client may experience greater benefits. It is also worth noting that the cultivation of a new and meaningful social contact could be equally beneficial to older people who are lonely but not socially isolated, suggesting that programs with this underlying mechanism could be widely advantageous for older people.

Mechanism 2: Provision of informal social support

In successful programs, it appears that the formation of a new and authentic relationship with the volunteer enables the volunteer visitor to provide informal support to the client much like a friend or family member would. Informal social support is conceptualized here as the social and personal supports received from friends, kin, neighbours, and other network members that exist outside of the formal social support system (e.g., public assistance) (Cantor, Reference Cantor1979), and includes support in the form of socialization, personal assistance, and advice, among many other forms of support. As volunteers and clients meet during the weekly or biweekly visiting sessions, isolated older people build up a new and trusting relationship (Mechanism 1). Once this relationship is built, the isolated individual may begin to reap the benefits of the informal support, which is crucial for retaining a sense of well-being in later life (Morano & Morano, Reference Morano, Morano, Gallo, Bogner, Fulmer and Paveza2006). Engaging in everyday activities, discussing mutual interests, and sharing stories are all examples of activities undertaken by volunteers, which may provide informal support and contribute to the reduction of social isolation and associated experiences (e.g., loneliness). Although the benefits of informal support may be less obvious and more difficult to measure when compared with the benefits of formal support, participants across the sample programs described multiple social benefits experienced as a result of the friendly visits. This informal support appears to act as a mechanism through which the isolated older person may receive assistance with aspects of their social network and/or personal life. As the volunteer and client meet repeatedly throughout the duration of the program, it is likely that this mechanism is triggered repeatedly and/or in an ongoing fashion.

Mechanism 3: Provision of mediated formal support

In addition to informal support, descriptions of programs in this sample suggest that volunteers are in some cases able to successfully provide mediated formal support. Whereas informal support may take the form of casual advice, active listening, and emotional connection, mediated formal support involves indirect assistance from a community organization or host agency through a third party (i.e., volunteer). Most descriptions of the programs included in the sample indicated an increase in knowledge of local amenities and services among their isolated clients. In some cases, friendly visitors accompanied clients to community groups and/or programs based on the guidance of the host organization. Together, these findings provide evidence for the role of the community agencies in these friendly visiting programs. Although the volunteer is the primary, if not only, individual directly interacting with the isolated client, it is clear that the host organization is playing a critical role behind the scenes.

The sample of studies identified several key contextual factors that appear to influence the triggering of this mechanism. This is articulated in part by Cheung and Ngan (Reference Cheung and Ngan2000), who describe the volunteers in their program as being mediators of the host organization. As mentioned, descriptions of many programs included in the sample mentioned volunteer training that typically touched on communication and listening skills. Several studies, however, described training modules specifically pertaining to seniors’ services and programming in their respective areas. This training appears to be crucial in terms of capacity building for volunteers and their ability to link older people to available services, particularly as many older people are not aware of the services available to them in their local area (Denton et al., Reference Denton, Ploeg, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2008). In some instances, programs in the study provided supervision and/or check-in meetings for volunteers where clients’ needs could be discussed with the program organizers and other volunteers. By enabling volunteers to seek individualized guidance and advice regarding recommended services and supports for their clients, volunteers are then able to direct this support towards the isolated individual.

Program Theory

This theory depicts three primary mechanisms that appear to contribute to the success of friendly visiting programs aimed at ameliorating social isolation among older people (Figure 2). The three mechanisms are depicted by the white nodes. Important contextual factors that are theorized to influence these mechanisms are depicted in the blue nodes. As previously described, these contextual factors are the elements thought to determine in part whether or not the mechanisms are “triggered”. The three theorized mechanisms (and their accompanying contextual factors) are intentionally depicted in a sequential order. We have theorized that the development of a new and meaningful relationship between the program participant and volunteer is one mechanism, and the provision of support (formal and informal) are conceptualized as separate mechanisms that repeatedly trigger (or fail to trigger) throughout the duration of the friendly visiting scheme. Based on the evidence gathered in this review, we have theorized that it is the combination of these mechanisms, when triggered successfully under the influence of certain contextual factors, that have the potential to explain how and why friendly visiting programs can lead to such positive outcomes among certain participants. The yellow node represents a positive outcome in the intervention. We have intentionally used the terms “reduced isolation” and “improved connection” to account for the fact the studies included in this review differed with respect to what type of outcome they deemed successful.

Discussion

Unlike other types of reviews that may focus on if programs work, realist reviews concentrate on how, for whom, and under what circumstances programs work. The results of the realist review presented here provide a starting point for the development of effective friendly visiting programs aimed at reducing social isolation among older people by illuminating mechanisms and contextual factors that may bring about a positive outcome. The mechanisms identified highlight the ways in which these types of programs may have meaningful impact on the lives of those participating, and the vital contextual factors identified provide important insight into when and how these mechanisms may be “triggered”. Together, results present several implications for future research and program development.

The findings in this study underscore the importance of matching clients and volunteers that are on some level compatible. As mentioned, however, many of the studies included in the sample provided little detail pertaining to how and why pairings were made. Aside from basic requests for a volunteer of a specific gender, it is not clear what may constitute a best practice. This gap represents a noteworthy area for future consideration and may have significant implications for certain sub-groups of older people. For example, LGBTQ+ older people may experience additional vulnerability to social isolation as a result of victimization, discrimination, and other life course factors (Perone, Ingersoll-Dayton, & Watkins-Dukhie, Reference Perone, Ingersoll-Dayton and Watkins-Dukhie2020). Additionally, language barriers among language minorities can present significant access issues in terms of both formal and informal support (Scharf, Shaw, Bamford, Beach, & Hochlaf, Reference Scharf, Shaw, Bamford, Beach and Hochlaf2017). It is therefore critical that program developers and researchers alike consider ways in which social isolation interventions can be adapted to support varying levels of risk and need. Developing best practices for matching volunteers and clients in friendly visiting programs could help to ensure that these types of programs are safe, accessible, and inclusive of older people with a variety of identities and backgrounds.

Results highlight the immense value of educating older people about the services and amenities in their respective communities. Although on the surface this finding may seem slightly removed from the end goal of re-connecting socially isolated older people, the implications of increased awareness of services are likely far-reaching. A study of adults 50 years of age and over found that many older people are not aware of the community support services available to them (Denton et al., Reference Denton, Ploeg, Tindale, Hutchison, Brazil and Akhtar-Danesh2008). Furthermore, older people experiencing social exclusion are often marginalized from accessing local services (Scharf, Phillipson, & Smith, Reference Scharf, Phillipson, Smith, Walker and Hennessy2004). Connecting isolated older people with supportive volunteers who are knowledgeable about local services may therefore represents an important first step in re-engaging these isolated people with supports in their communities. Indeed, the benefits that may be derived here can go a step further if and when the host organization has a direct connection to a service agency or program that may provide these services and supports.

The findings also pose questions related to gender diversity and participation. The studies in this sample tended to include more women than men in both the evaluation component (i.e., sub-sample) and the full study population (when applicable). This is in many ways representative of wider trends in social programming whereby older men are less actively involved than older women (Golding, Brown, Foley, Harvey, & Gleeson, Reference Golding, Brown, Foley, Harvey and Gleeson2007). A portion of this participation discrepancy may also be the result, in part, of the reality of life expectancy differences between men and women, and the “social gatekeeping” roles often held by women in long-term heterosexual relationships that often leave male partners with few high-quality social contacts following divorce or widowing (Wister & Strain, Reference Wister and Strain1986). As evidence mounts pertaining to the rise of both isolation and loneliness among older men (Beach & Bamford, Reference Beach and Bamford2014), it is more important than ever for program developers and researchers to redouble their efforts to include greater gender diversity in program design and related research and evaluation. Furthermore, the active inclusion of gender minorities (e.g., transgender men/women, non-binary older people) is a critical next step in the development of all social isolation interventions. Gender diversity and inclusion is necessary for the well-being of all older people.

The findings also raise several questions about temporal aspects of friendly visiting programs. The sample of studies included in the analysis varied greatly in terms of both the duration of the friendly visiting program (e.g., 6 months, 1 year), and frequency of visits (e.g., weekly, biweekly). As such, we were unable to identify any significant demi-regularities or contextual factors linking program duration to outcome. Likewise, studies in this sample conducted evaluations, both surveys and interviews, at different points in time (e.g., 1 month post-program, 3 months into the active program) rendering it nearly impossible to draw meaningful conclusions about the lasting effects of these programs. Although it may not be feasible in all cases because of practical constraints, we recommend that future evaluations of friendly visiting programs include outcome measurements at various points in time – particularly post-intervention – to clarify these outstanding questions.

The findings from this review flag critical questions about evaluation and outcome measurement as well. Across the studies included in the sample, several different outcome measures were used to determine program “success”, in addition to qualitative outcomes that did not rely on scales or objective measurements. This is commonplace in realist syntheses but can pose a challenge in certain scenarios. Within the broader social isolation literature there exists significant dialogue and debate related to objective isolation, perceived isolation, loneliness, and how these various experiences intersect and/or potentially overlap (Smith & Victor, Reference Smith and Victor2018). When comparing quantitative studies using different outcome measures (i.e., quality of life, social support scales), it can be challenging to compare various instances of success, particularly when scale or quantitative outcome measures are built to measure distinct constructs or experiences.

This problem can be further exacerbated when one considers that many studies articulate a goal to ameliorate one problem (e.g., social isolation) but benchmark their success on the outcome of a different experience (e.g., life satisfaction). In principle, the connection between the two concepts may not be so far-fetched, and there may in fact be a theoretical justification for why a change in one experience may bring about a measurable change in another experience. Yet, if researchers fail to provide adequate detail regarding the proposed underlying mechanism through which this may occur, knowledge users may overlook critically important connections. Indeed, O’Rourke and colleagues conducted a scoping review of social connection interventions for older people and found that there were many inconsistencies in the literature “regarding the mechanisms by which the interventions have been conceptualized to affect loneliness/social connectedness” (O’Rourke, Collins, & Sidani, Reference O’Rourke, Collins and Sidani2018, p. 10). They then go on to conclude that in many of these programs, it may not be possible to determine the extent to which a given intervention actually achieved what it set out to achieve (O’Rourke et al., Reference O’Rourke, Collins and Sidani2018). We raise this consideration because social isolation is often conflated with associated concepts; namely, loneliness and living alone, despite continued efforts to build a unified typology (Machielse, Reference Machielse2015; Smith & Victor, Reference Smith and Victor2018). Future efforts should consider methods of avoiding the conceptual confusion amongst these related social concepts and outcomes by clearly outlining inclusion and exclusion criteria among potential participants and providing operational definitions where applicable. These considerations would go a long way in supporting subsequent program development and scholarship.

The last consideration relates to the optimal time to intervene in the trajectory of social isolation. We have seen in this study that friendly visiting programs hold great promise for improving the lives of older people who are isolated, in part because these programs are cost effective and replicable across a variety of settings. And yet, social isolation remains a highly complex and harmful social outcome that can reduce life expectancy, increase risk of death by suicide, and contribute to depression (Holt-Lunstad et al., Reference Holt-Lunstad, Smith and Layton2010; Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012). Evidence has also suggested that the longer someone lives in a state of social isolation, the more difficult the task may be to re-socialize them (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Gavin, Begley and Brodie2003; Machielse & Duyndam, Reference Machielse and Duyndam2020). Likewise, there is no universal intervention that will serve as a cure-all for social isolation in later life (Machielse & Duyndam, Reference Machielse and Duyndam2020). However promising friendly visiting programs and other interventions may be, the literature clearly points to prevention as being the primary means through which to tackle the ongoing concern of social isolation. As such, we encourage program developers, researchers, and policy makers alike to consider ways in which older people may be supported and empowered, particularly individuals who may be experiencing multiple forms of risk and/or vulnerability. Governing bodies and service providers must consider novel methods for identifying those who are at risk in order to intervene and prevent the onset of social isolation when possible. This may include developing risk assessments for unique risk factors in various residential or institutional settings (Boamah et al., Reference Boamah, Weldrick, Lee and Taylor2021), and enhancing age-friendly policies more broadly to promote the meaningful participation and inclusion of older people in their communities (de Biasi, Wolfe, Carmody, Fulmer, & Auerbach, Reference de Biasi, Wolfe, Carmody, Fulmer and Auerbach2020; Syed et al., Reference Syed, McDonald, Smirle, Lau, Mirza and Hitzig2017). This is a considerable and yet necessary task if the goal is to tackle late-life social isolation directly.

Limitations

The realist synthesis presented in this article is subject to several limitations. First, many studies of friendly visiting/befriending programs were not included in the final sample because sufficient detail regarding process, methods, participants, or other important factors was not included. Because of the nature of realist reviews, studies may only be included in the analysis if authors provide detailed information about the intervention and how it was conducted. This can often present challenges for researchers undertaking realist syntheses. In fact, other realist evaluations (see Wong et al., Reference Wong, Greenhalgh and Pawson2010) have also found that many primary studies did not include sufficient detail pertaining to process and implementation of their respective interventions or programs. It is therefore our recommendation that, when publishing outcome studies, those conducting evaluations of social programming take care to provide detailed accounts of how the programs were implemented. This information likely holds the key to learning from past failures and successes. Without it, evaluators and program developers may be inadvertently experiencing similar pitfalls or barriers time and time again.

Second, several studies were excluded from the final sample because of the conflation of and/or lack of separation between loneliness and isolation. Many of the studies included in the analysis discuss both social isolation and loneliness, although distinctions were made to recognize the crucial differences between the two inter-related concepts. However, other studies that conflated the terms “social isolation” and “loneliness” were not included. This particular problem is long-standing within the social isolation literature and is exceedingly problematic. As it stands, there is no universal definition of social isolation, but most scholars tend to agree that it involves objectively low social support and/or few social contacts, whereas loneliness is typically described as a subjective feeling (Smith & Victor, Reference Smith and Victor2018; Victor et al., Reference Victor, Scambler, Bond and Bowling2000). Unfortunately, many scholars continue to confuse the two terms and use them interchangeably (Fakoya et al., Reference Fakoya, McCorry and Donnelly2020). This ongoing dilemma has impeded progress in social isolation research and will likely continue to pose a challenge until clear boundaries are drawn between the two concepts by those conducting the research and evaluation. Nevertheless, we recognize that an effective friendly visiting program that intends to reduce social isolation is also likely one that will address and reduce loneliness simultaneously.

Conclusion

Friendly visiting programs have the potential to provide effective social support to socially isolated older people in a variety of contexts. The results of this realist synthesis begin to unravel the mechanisms that may be responsible for the success of these programs, and provide a preliminary blueprint for programmers looking to address social isolation and loneliness. It is our hope that the mechanisms identified in this review will be tested and refined. We encourage program organizers, where possible, to develop friendly visiting programs that: (1) encourage meaningful relationships between volunteers and participants by carefully matching volunteers and participants based on preferences and values, (2) promote the sharing of informal support via effective volunteer training and matching, (3) prompt the delivery of formal support by emphasising connection with participants and providing effective supervision of volunteers, and (4) evaluate the efficacy of these components using thorough evaluation methods. When applicable, this could include developing a program logic model, conducting pre- and post-intervention surveys, administering validated instruments or scales, conducting interviews with clients and volunteers, and maintaining detailed documentation of all planning and implementation details. These efforts will provide the evidence needed to determine the extent to which this program theory accurately explains the mechanisms that underly successful visiting programs. As there exists a wide variety of social isolation interventions following different program theories not covered in this synthesis (e.g., arts-based programs, support groups), it is also our recommendation that others conduct additional syntheses. More evidence is needed to determine when, where, and for whom interventions may be most beneficial, and realist reviews can begin to address these gaps.

Funding

This work was funded by the Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship. The funder was not involved in the production of this piece.