Health technology assessment (HTA) is conducted and used by government and quasi-governmental bodies in most high-income countries and an increasing number of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and it has become a critical step for access to, and reimbursement and pricing of, health technologies. Whether HTA-informed decisions are viewed as legitimate, fair, and transparent is closely linked to the concept of deliberation, defined generally as the critical examination of an issue (by one person or a group) involving the weighing of reasons for and against a course of action (Reference Gauvin1). Within HTA circles, this definition has been taken to suggest a series of coordinated activities (e.g., review of clinical and economic data), allowing a group of people to receive and exchange information, to critically examine an issue, and to come to an overall group judgment (Reference Gauvin1). This group judgment can constitute a binding decision, take the form of a general recommendation, or inform a subsequent decision.

Deliberative processes are not new to HTA and their important connection to a reasonable and fair approach for making decisions regarding access to health technologies is generally acknowledged. One prominent use of a deliberative process in HTA is that used for making reimbursement and access decisions for healthcare technologies, including pharmaceuticals, medical devices, surgical procedures, and diagnostics tests. Deliberations may involve examining the uncertainty of evidence and the weighing of those factors for which there is valid information (quantitative and qualitative) to arrive at an overall decision. These deliberative processes, it is argued, provide the best way to combine complex sets of evidence, perspectives, and values (Reference Douglas2), while also allowing these aspects to be identified and openly discussed, thus making reimbursement and other HTA-supported decisions more inclusive, transparent, and trustworthy (Reference Hofmann, Cleemput, Bond, Krones, Droste and Sacchini3). Deliberative processes in HTA have been established in most high-income countries, and some process elements, for example, those of England's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), Canada's Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), and the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC), are seen as references for those seeking to establish new deliberative processes or to strengthen existing processes (Reference Oortwijn, Determann, Schiffers, Tan and van der Tuin4). There is evidence illustrating that the expert or advisory bodies making access and reimbursement decisions, even those within similar health systems, reach different conclusions regarding the same technologies for a variety of reasons. Yet, there is little documentation and research to inform the design and development of effective and efficient deliberative processes (5;6), and both producers and users of HTA, as well as a range of stakeholders, are interested in better understanding why and how particular HTA decisions are made with the intent of improving the legitimacy, consistency, and quality of these decisions more generally.

In light of these interests and opportunities, the HTAi Global Policy Forum (GPF) (https://htai.org/policy-forum/global-policy-forum/) selected deliberative processes in HTA as the topic for its meeting held 26–28 January 2020 in New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. The meeting was attended by eighty participants from twenty-two countries representing fourteen not-for-profit organizations (public HTA agencies; private HTA organizations, public and private payers, representing in part the perspective of the tax- and premium-paying public; and health systems), seventeen for-profit organizations (pharmaceutical, biotech, and device companies), HTAi leadership, and invited speakers (Supplementary Table 1). The objective of the meeting was to review and discuss both challenges and opportunities in managing the deliberative process, to learn about novel approaches to and innovations in deliberation, and to agree on a set of core principles and supporting actions around the deliberative process to help move the field forward. While there are various components of HTA processes where deliberation may be used, the GPF meeting focused specifically on deliberations for pharmaceutical adoption and reimbursement decisions.

This article provides a summary of the discussions held at the 2020 GPF meeting. The meeting was conducted under the Chatham House Rule (7), whereby participants are free to share information obtained at the meeting, but they may not reveal the identity or affiliation of the person providing the information. Our summary presents the authors' view and is not a consensus or other statement from individuals who attended the meeting or of their organizations; this summary is intended, in part, as an invitation to others involved in HTA to discuss and debate the issues raised.

Meeting Structure and Proceedings

To inform the meeting discussion and activities, a background paper was developed (Reference Bond8) based on issues identified in the scientific and grey literature, through semi-structured discussions with a convenience sample of seventeen expert informants selected to represent a variety of stakeholder perspectives and content knowledge, a review of relevant HTA agencies' Web sites and documents, and input from the GPF Organizing Committee, GPF members, HTAi Board members, and the wider HTA community. The background paper described various aspects of deliberative processes that may influence decisions and identified aspects that may present opportunities for encouraging efficiency and consistency, including potential stakeholder involvement, in each aspect of the process. Examples of the former include whether a committee reaches a decision by consensus or majority vote and the form of patient input into deliberations. Examples of the latter include having a technical sub-committee that makes an initial recommendation based on clinical and economic evidence or preserving time for the committee members to discuss differing views (Reference Bond8).

Participants were also given a “Guide for Construction of Principles,” in advance of the meeting (Reference Bond9). Principles for deliberative processes are often characterized as being either substantive or procedural in nature. Substantive principles specify the normative criteria or reasons that ought to provide the basis for priority setting decisions to cover particular health technologies or not; procedural principles describe characteristics that ought to be present in priority setting processes (Reference Clark and Weale10). The guide described eleven draft principles for deliberative processes and associated supporting actions for GPF members to use as a starting point for discussion, and was gleaned from multiple sources in the HTA and broader ethics communities (11). The principles refer to “highly generalized right-making characteristics of actions or rules that govern actions” (Reference Veatch12), in this case, actions related to a deliberative process and its outcome. For example, a “principle of consistency” might articulate the belief that the consistent application of a process and decision criteria by a deliberating body is an important characteristic of an appropriate recommendation or decision process. The supporting actions are a way of specifying individual principles to indicate how a principle might guide action within this context and to encourage an iterative process of reflection on and accommodation of the principles in light of the outcome of their application in specific cases (Reference Daniels13). In the case of consistency, an associated action could be that the deliberating body will provide a clear description of whether a decision is similar to judgments in previous cases, the aspects that made it similar, and how it may have differed in important respects.

Large and small group discussion was used to enable participants to reflect and comment on the draft principles. Live polling, using a real-time tool, was also employed to gather feedback on the acceptability and priority of suggested principles and actions and to generate further reflection and discussion among meeting participants. A list of “core principles” was developed through three rounds of polling (Figure 1). As polling rounds progressed, principles that were suggested by participants were added and other principles were removed, and some principles were identified as being part of other principles. GPF participants were asked to score each of the eleven draft principles on a four-point scale according to its perceived importance for producing legitimate and fair deliberative decisions across HTA processes and contexts: 1 = not important; 2 = somewhat important; 3 = important; 4 = very important. Decisions about which principles would be carried forward for discussion were based on majority vote.

Figure 1. Identification of “core principles” for deliberative processes.

After discussion in large and small groups about what supporting actions might be needed for the three most important principles, a poll was conducted that asked participants to rate a list of potential supporting actions for each of the three principles as: 3 = important for any setting; 2 = important, but may be more so in some settings than others; and 1 = not important and/or difficult to implement. A mean score of 2.5 was employed as the cutoff for retaining actions on the belief that a score of 2.5 or greater indicated that the action is important and likely to be realizable in any HTA setting.

To help facilitate and structure discussion about principles and actions, the deliberative process was conceptualized in terms of five components using an “input-throughput-output” (ITO) model (Figure 2). The ITO model describes a deliberative process in terms of five different aspects: (i) the way in which deliberators are identified and selected and the general conditions under which the committee will conduct deliberation and reach decisions; (ii) the collection of information that forms the basis for deliberation; (iii) the individual cognitive and relational aspects that enable the presentation and weighing of facts, values, and reasons that lead to a collective judgment (including formal decision frameworks such as MCDA); (iv) the way in which the content and result of the deliberation is communicated and learning is consolidated; and (v) the opportunities within the process where important stakeholders such as patients, clinicians, manufacturer representatives, and payers might provide input and participate in other ways to better fulfill the aims of the deliberative process. Some researchers consider deliberative processes in HTA to encompass a broad range of decision points and activities, including topic identification, scoping, and appeal (Reference Oortwijn, Jansen and Baltussen14). As illustrated in the ITO diagram, the deliberative process, as considered by GPF participants, was not this expansive.

Figure 2. Input-throughput-output model.

A keynote presentation was delivered each day on a specific topic relevant to the discussion of principles and actions for deliberative processes. The keynote presentations addressed, respectively, thoughts about the history and development of deliberative processes in HTA at NICE, innovations in deliberative processes in HTA (specifically in the context of ongoing experimentation in South Africa), and approaches to successful patient and citizen involvement within HTA reimbursement deliberations. The keynote presentations, as well as case studies presented by GPF members and panel discussions, provided members with the opportunity to think about the importance of various activities within deliberative processes from a variety of stakeholder perspectives, and to learn about innovative approaches for strengthening such processes.

Two panel sessions provided important reflections on the potential benefits and challenges of common principles and actions for deliberative processes. The first panel consisted of four GPF industry representatives, who shared their thoughts on what the global pharmaceutical and medical device industry might hope to achieve by adherence to a set of commonly accepted principles and what responsibility industry might play in addressing major gaps. The panel discussion centered on three main themes: the importance of the context of deliberation and decisions, how to better involve patients and incorporate patient-important information in deliberations, and the role of industry on deliberative committees. The discussion highlighted the fact that evaluations and reimbursement decisions must be made locally, which means, for example, that developing markets in LMICs cannot simply take the reimbursement recommendations or decisions from developed markets and apply them to their settings. This reflects the lack of transferability of evidence as well as that of social and political values. Additionally, identifying patient-important outcomes and other aspects important for deliberation need to be identified and assessed in a way that is considered methodologically rigorous and acceptable to decision makers. Finally, it was noted that having an industry perspective in deliberative committees can help to strengthen the knowledge and diversity of committees and potentially increase the acceptability to the industry of the process and the resulting decisions.

The second panel session consisted of four GPF members who provided reflections from the perspectives of an HTA agency, a patient organization, industry, and a payer on the importance of partnership as a guide to thinking about what might be required to involve stakeholders in a constructive and meaningful way. Discussion highlighted that including patients requires reflecting on why patients are being involved in a specific part of the deliberative process and clarifying and supporting those roles, identifying opportunities for a stronger involvement in evidence generation, developing communication materials and methods guidance, and bringing payer perspectives into the discussion.

Meeting Output

The ITO model proved helpful in fostering discussion about a complex process. It was also noted that the traditional boundary between “assessment” and “appraisal” is perhaps not as clear-cut as has traditionally been assumed, and the terms are often used interchangeably. This distinction assumes that there is a clear separation between facts and values within HTA in processes where these elements are considered to be collected and analyzed separately from one another and are then “integrated” through an appraisal process, for example, deliberation (Reference Hofmann, Bond and Sandman15). The ITO model, and the feedback loops between the activities, helped to show why this traditional distinction is problematic and highlighted the need for principles to cover the entirety of the deliberative process (leaving open the question of whether and how these principles might apply to other aspects of the HTA process).

“Core” Principles and Supporting Actions

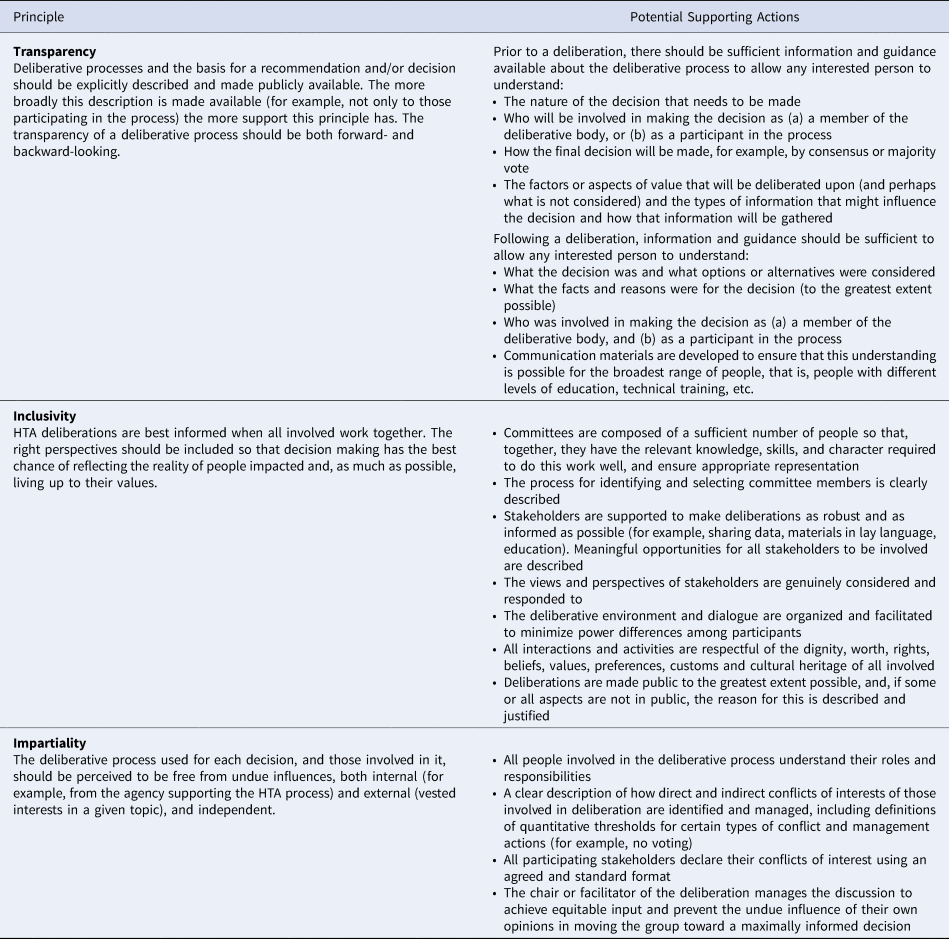

The most common principle suggested by members, in addition to those provided in the Guide, was respect, followed by common sense, evidence-based, efficiency, adaptability, validity, patient centricity, timeliness, uncertainty, and coherence between substantive and procedural values. The third round of polling found strong agreement among members for three principles: transparency, inclusivity, and impartiality (Figure 1). The three principles were not ranked in order of importance or by the need to satisfy any one before the others. In addition, GPF members discussed and described the actions that can be undertaken to support each of the principles within deliberative processes (Table 1).

Table 1. Core Principles and Actions for Deliberative Processes in HTA

Transparency

Transparency refers to the importance of explicitly describing, and making publicly available, information on the deliberative process and the basis for a recommendation or decision. Transparency of the entire deliberative process promotes accountability and legitimacy and allows stakeholders to judge whether the deliberative process and the resulting decision is fair. Associated actions for this principle include providing sufficient information for any interested person to understand who will be involved in the decision, how the decision will be made, and what aspects of value will be deliberated upon. A concrete example of transparency of this kind is provided by the chair and deputy-chair of Australia's Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) speaking directly with patient groups and other stakeholders to explain PBAC decisions, their context, and the deliberation.

Inclusivity

Inclusivity refers to the importance of bringing the right perspectives together so that decision making has the best chance of reflecting the reality of people impacted by the decision and living up to their values as much as possible. Achieving inclusivity requires, among other things, fostering a deliberative environment in which stakeholders can meaningfully share their views, and minimizing power differences among participants. For example, the SMC PACE (Patient and Clinician Engagement) meetings provide an opportunity for patients and clinicians to provide information on the added value of a medicine that may not be captured through the typical reimbursement review process.

Impartiality

The principle of impartiality recognizes that the deliberative process used for each decision, and those involved in it, should be perceived to be free from undue influences, both internal (e.g., from the agency supporting the HTA process) and external (vested interests in a given topic). Some actions that support this principle are a clear description of the process for identifying and managing perceived conflicts of interest among all participants in the process, and the meeting chair managing discussion in a way that allows deliberators to have equitable input. In practice, many committees require the public declaration of conflicts of their members prior to deliberation and have a defined conflict of interest threshold beyond which participation in the deliberation is not allowed.

While members agreed most strongly on the overall importance of transparency, inclusivity, and impartiality, other principles were supported also to varying degrees. Members reiterated the need to think further about reviewability (e.g., update of an appraisal vs. appeal of a decision) and what that means, as well as the importance of consistency and need for clarity about what is being identified to avoid misinterpreting this as sameness of decision rather than as the consistent application of a process (“predictability” was suggested as an alternative). There was also some debate as to whether consistency was in fact an important principle because it was thought that adhering to this principle might prevent deliberative processes from responding to the need for change or allow for appropriate variability between HTA settings.

Respect was another principle and it was suggested that this might be considered a part of inclusivity. However, some members believed respect is distinct and important enough to be recognized as a stand-alone principle; others argued respect is an attitude rather than a process characteristic. There was also discussion about whether other concepts, such as integrity and timeliness, capture important values of this process. Reasonableness was also considered by many to be a characteristic of the entire deliberative process, and that reasonableness might be thought of as a precondition for realizing the other principles. Likewise, the principles of respect and accountability might also be better thought of as preconditions to the entire deliberative process. Discussion also highlighted that the principles are meant, in part, to be aspirational—ideals that HTA organizations and all stakeholders might strive to uphold. Relatedly, the general point was made that the three principles (and perhaps others) could be adopted as long as they do not conflict with an agency's organizational values. It was argued that all relevant principles should be mentioned, even if they are not currently supported in particular cultural or political contexts, so that they may be promoted.

In practice, the principles may conflict with each other and it was recognized that specifying the actions is particularly important to help guide agencies and stakeholders to navigate this conflict and to make explicit what is being done to live up to the principles being espoused. For example, an agency might be transparent about managing conflicts of interest, but may still not achieve impartiality, which requires the balancing of views. Agencies may also be pressured to operationalize actions in a way that is not feasible, for example, by having lengthy patient input processes to support inclusivity. It was believed important to be able to explain that certain actions supporting one principle might conflict with the need to satisfy another principle or to contend with some practical limitation.

The actions developed for the three proposed core principles help to specify what HTA agencies should do and what activities they should support to live up to each of the principles. The participants discussed the potential need to separate scoring of whether actions are deemed important from the scoring of whether they are feasible or implementable in various contexts. Suggestions were made about how the proposed actions might be modified in various ways and where potential challenges might arise. For example, achieving transparency requires trust on the part of all stakeholders, limits on what is kept confidential to the bare minimum necessary to protect stakeholder interests, and buy-in among all involved. Achieving inclusivity requires sensitivity to patient preferences for engagement, and recognizing the diversity of input, for example, clinical input must strive to include many provider types, including physicians, nurses, and social workers.

Practical Limitations on Principles and Actions

Important characteristics of deliberative processes, such as timeliness, have been suggested as principles. We believe such characteristics are best seen as aspects of management that influence the implementation of a deliberative process rather than as principles (see references (Reference Bond8) and (Reference Bond9) for further discussion). These aspects of management will vary according to the social, cultural, political, economic, and legislative context within which a deliberative process occurs. What “timeliness” means will vary according to the decision-making demand by a particular government or set of payers, and this demand will restrict the range and duration of actions that might be taken to support principles such as inclusivity or transparency. Other examples of practical limitations include the breadth of responsibility for the HTA agency (based on its legislative authorization or mandate); cost; technical specifications, such as facilities for those not able to attend in person; and translational aspects of reviews, such as producing lay-friendly summaries. Practical limitations are important to identify because they influence what actions might be achievable within local contexts and set the standard that should be used to judge the success of a particular deliberative process.

Implementing Principles in Different Contexts

Regional considerations (cultural and political relevance and transferability) are very important, and it was noted that it would be essential to see how HTA stakeholders from other regions might view the three principles and their associated actions to better gauge their broad acceptability. There may be large differences in attitudes and approaches toward the proposed principles and actions, and this will be important to understand.

The discussion also highlighted the challenges, political background, and other preconditions for implementing deliberative processes. Some principles may be part of legislation in some contexts, and so they may be more easily promoted and upheld. While there was general congruence among attendees about what some principles meant, this was not always the case. The challenge and importance of working across languages and political contexts in developing the principles was noted as an important consideration and something that may lead to differences of opinion about the relative importance of each principle. For example, not all languages will make a distinction between the terms “accountability” and “responsibility.” Likewise, reviewability is seen as integral to any public process in some contexts, but not so in others.

It is also important to note here that the deliberative processes considered within the background materials, and most processes referred to in discussion, were established in Western, high-income countries. LMICs are also interested in establishing deliberative processes as part of their healthcare priority setting. The HTAi Latin American Policy Forum has indicated the need for best practices in the region (Reference Pichon-Riviere, Soto, Augustovski, Garcia Marti and Sampietro-Colom16), while also emphasizing that principles of good practice cannot be uncritically adopted from their application in high-income countries—any such principles must respond to the contextual realities of countries striving to adopt and establish HTA systems. Some LMICs may face particular challenges in adopting and promoting the three principles because of a history of corrupt decision making, poor management of conflicts of interest, and lack of capacity for producing scientific evidence, as well as a lack of political will to use that evidence for policy making. Similarly, researchers examining HTA systems in Central and Eastern Europe have urged that there is no single or common direction for HTA development, and that the institutionalization of HTA should proceed according to a country's developmental stage and the characteristics of the health system (Reference Garcia-Mochon, Espin Balbino, Olry de Labry Lima, Caro Martinez, Martin Ruiz and Perez Velasco17).

With respect to achieving inclusivity, it may be difficult to engage patients and citizens for various political or cultural reasons in certain settings. In particular, a lack of understanding around the key goals of the process, and the opportunities for engagement, as well as difficulty understanding important technical information that is part of deliberation, such as cost-effectiveness analyses, are often challenges. It may also be challenging to foster participation if there is no direct interest at stake in the decision. Nevertheless, if patients are given the right background and context to be able to contribute effectively, there is significant merit in patients contributing to the discussion, for example, by providing important insights about patient-relevant end points, factors not captured by the value determination, and patient-borne costs. It is therefore critically important that all participants and stakeholders in deliberative processes receive sufficient education to understand what is being discussed and its relative importance to the process. Indeed, this support for transparency and inclusivity has been highlighted by others as fundamental to promoting the fairness of resource allocation decisions (Reference Rid18).

Discussion

The idea of a set of “core principles” is common within biomedical and health policy ethics; prominent examples include Beauchamp and Childress's four principles of biomedical ethics (respect for autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice) (Reference Beauchamp and Childress19) and Daniels and Sabin's four conditions of “accountability for reasonableness” (publicity, relevance, appeal, and enforcement) (Reference Daniels and Sabin20). Nevertheless, there is a long-standing debate about the extent to which such sets of core principles are sufficient to capture the range of concerns that are important to decisions (21;22;23). For example, some have argued that the conditions of accountability for reasonableness might be supplemented by a principle of empowerment (Reference Gibson, Martin and Singer24) and a condition of impartiality (Reference Rid18). The vigorous discussion among GPF members suggests that there is likely similar uncertainty regarding the sufficiency of the three core principles described here and the important concerns of deliberative processes in HTA. Nevertheless, we believe a set of broadly accepted core principles can help avoid the opposing risks of moral relativism (any principles will do) and a restrictive moral imperialism (there is one and only one set of correct principles) regarding deliberative processes in HTA.

Within HTA, there is debate about the appropriate balance between substantive and procedural principles. The three core principles (transparency, inclusivity, impartiality) would usually be considered procedural, though some might argue that they can be construed as substantive principles. While participants settled more easily on these ostensibly procedural principles, this should not be taken as an indication that GPF members promote a proceduralist approach to deliberation, and, as noted above, there was a vigorous debate about the relevance and importance of more clearly substantive principles such as respect. Indeed, some have argued that securing social legitimacy, transparency, accountability, and consistency in health resource allocation decisions requires both substantive and procedural principles (Reference Biron, Rumbold and Faden22). While countries that engage in deliberative processes for HTA typically include substantive and procedural values, it is interesting to note that some have argued that NICE has adopted an entirely proceduralist approach in the recent revision to its explicit statement of social values (Reference Littlejohns, Chalkidou, Culyer, Weale, Rid and Kieslich25).

Collections of principles can be criticized for being nothing more than checklists or headings of “values worth remembering,” and that do little more than point to ethical themes that merit consideration (Reference Beauchamp and Childress19). To address this, and to provide guidance for implementation, GPF members sought to agree on specific actions that HTA agencies and stakeholders might reasonably take to demonstrate a commitment to the three core principles. We believe these actions are an important contribution to the discussion about what principles ought to govern deliberative processes in HTA and how governments, HTA agencies, and stakeholders can benchmark and evaluate their adherence to these principles.

Next Steps

We cannot take for granted the various factors beyond the evidence itself that contribute to HTA recommendations. However, we have a poor understanding currently of how these factors influence decisions, for better or worse, and how fair and effective HTA processes can be best constructed in light of these potential influences. HTA agencies and ministries looking to implement new or strengthen existing deliberative processes should seriously consider formally adopting the three principles of transparency, inclusivity, and impartiality as defined here. In addition, they might use the associated actions as a starting place for determining what could be done to support these principles to the greatest extent possible within their specific operational contexts.

Based on the rich discussion among members, and the variety of perspectives that were considered, we provide suggestions below for what might be done to continue to make progress toward a set of defined best practices for deliberative processes within HTA:

• Beginning with the list of core principles and supporting actions developed at the 2020 GPF, those responsible for specific deliberative processes should attempt to document and share any practical limitations within their local context, and how these limitations influence the feasibility of and adherence to each principle within their HTA organization. This documentation should include features of the specific culture, health system, political structures, operational constraints, and other key contextual elements relevant to the HTA agency that may influence how the principles are interpreted and the feasibility of the proposed actions.

• While the three core principles were identified and developed through vigorous debate and discussion, additional principles may be added through other group consultations or dialogues. Those involved in various HTA societies and networks, such as HTAi, the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR), the International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment (INAHTA), HTAsiaLink, and the Health Technology Assessment Network of the Americas (RedETSA), should help to determine whether and how to integrate future conversations.

• Mature HTA bodies should rigorously document and periodically review their own composition and processes, examining variability among different committees, as well as impacts of changes to process and composition over time, clearly explaining the process and justification for changes.

• More comparative work should be done across HTA organizations to catalog and evaluate aspects of HTA composition, format, and deliberative models, especially among multi-country initiatives using similar evidence inputs, for example, the European Network for Health Technology Assessment (EUNetHTA), and similar collaborations and networks.

• As new HTA processes are developed and introduced in LMICs, research should be conducted to understand the potential implications of different appraisal and committee models, their resource requirements, and how to evaluate their quality.

Given the importance of deliberative processes in HTA and healthcare resource allocation decision making, agreement on a common set of core principles for deliberative processes that can be used globally would help strengthen the quality and consistency of these processes. The principles of transparency, inclusivity, and impartiality, as defined here, provide this starting point. Additionally, we have proposed concrete actions that might reasonably demonstrate that a deliberative process is designed and conducted in accordance with the three core principles. We hope that these core principles and actions provide a springboard for further research and better documentation of those aspects of deliberation that, while crucial, have been less well studied.

Acknowledgements

The HTAi Global Policy Forum (GPF) was made possible with the support of the members in providing funding and by attending and contributing to the discussions. We would like to thank the GPF Organizing Committee members for their guidance on this work: Joseph Cook, Pfizer, Inc, USA; Wim Goettsch, National Health Care Institute (ZIN), The Netherlands; Iñaki Gutierriez-Ibarluzea, Basque Foundation for Health Innovation and Research, Spain; Mark McIntyre, Boston Scientific, Inc., England; Andrew Mitchell, Office of HTA, Department of Health, Australia; Wija Oortwijn, Radboud University Medical Centre, The Netherlands; Gesa Pellier, Novartis, Inc., Switzerland; Jean Slutsky, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), USA. We would also like to thank the HTAi Secretariat for administrative and logistical support for the meeting, and the GPF 2020 meeting participants and invited speakers for their engagement and dedication to developing the principles and actions. Full details of the GPF members can be found on the HTAi Web site and attendees of the 2020 meeting are shown in the Supplementary Table.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462320000550.

Financial Support

No external funding was used in the research or production of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors were funded by HTAi to report on the meeting. KB and RS declare that they have no other potential financial or nonfinancial conflicts. DO reports grants and other funding from HTAi, during the conduct of the study; other from CEA Registry Sponsors, personal fees from EMD Serono, personal fees from Amgen, Analysis Group, Aspen Institute/University of Southern California, GalbraithWight, Cytokinetics, Executive Insight, Sunovion, and the University of Colorado.