One day in early August 1914, Count Robert Keyserlingk-Cammerau, Prussian governor of Königsberg, was unpleasantly surprised by a knock on his door. His cousin Alfred, imperial administrator of Tsarskoe selo, Tsar Nicholas II’s summer residence near St. Petersburg, was seeking his hospitality for the night. Under normal circumstances, the cousins would have been delighted to meet. This time, however, their meeting created an ethical dilemma. War had broken out in Europe only a few days earlier, a conflict in which the states whose imperial families they served were on opposing sides. Robert, a German imperial civil servant, was obliged to follow orders of his government, which was to arrest any Russian subject found in Königsberg. Alfred had been surprised by the war while travelling in Germany on personal business. He knew that his male staff , some 250 people, were about to be conscripted into the army, leaving the administration of the estates in his hands; he had to get back to St. Petersburg urgently. Finally, he managed to secure a makeshift seat in the toilet cabin of the last, overcrowded train leaving Berlin for Russia, but then got stuck in East Prussia, near the Russian border where, allegedly, Cossacks had disrupted trains passing to Russia. The guards on the train were instructed to take into custody and bring back to Germany all Russian subjects. Alfred narrowly escaped and made his way to Königsberg’s Altes Schloss, where he knew his cousin was resident.Footnote 1

For one night only, familial ties trumped political allegiance. Before sunrise Alfred departed in his cousin’s official car, past the Prussian guards, to the train station. Having to seek an indirect route back to Russia, he returned to Berlin and took the train to Hamburg, then boarded a boat to Sweden. Personal connections to two famous Petersburgians, the Swedish petroleum magnate Alfred Nobel and the Petersburg delicatessen merchant Grigory Yelisseev, allowed him to board their private steamer, one of the few still operating on the route back to Petersburg. However, only a few days after his arrival there, he was arrested once again – this time, by the Russian gendarmes – and was taken to the Peter and Paul fortress on charges of espionage for Germany. During the ensuing Russian Revolution and Civil War, Alfred joined Kolchak’s ‘white’ army in Siberia, which eventually lost to the Bolsheviks. Robert Keyserlingk became the German Commissioner for Lithuania and the ‘eastern territories’ before taking a post in St. Petersburg, now called Petrograd, as a military attaché, where he sought to promote German interests in Russian monarchist circles.Footnote 2 Moving to Berlin after the failure of this campaign, he eventually completed his political career in the Federal German Republic as a member of the Prussian Council of State and German agricultural policy advisor at the new World Economic Forum in Geneva.

Such foreign connections could be a curse and a blessing at the same time. For example, Alfred Keyserling, in addition to being a Russian subject and civil administrator of the Tsarskoe selo district, as well as a member of the Courland nobility, was also the founding co-owner of Baltic Lloyd, a commercial navigation agency originally co-financed by Bremer Lloyd and serving the ports of Libau, Emden, and Bremen.Footnote 3 By the twentieth century, the sort of internationalism that Keyserling and his cousins practised professionally and socially appeared to some, especially to Russians and Germans, like acts of treason.

Today, historians speak of the Great War in an increasingly cosmopolitan sense. The parties that went to war in 1914 were half conscious ‘sleepwalkers’, a reader learns in 2013, and the imperial or national interests they represented were at least one level of scrutiny removed.Footnote 4 The very idea of war has become broader, comprising the home front and the economic and cultural aspects of life in wartime.

But at the time of the First World War, having a cosmopolitan perspective on the theatre of war was the prerogative of the imperial elites. These included aristocratic families like the Keyserlings, whose familiarity with the administration and economic structure of more than one empire gave them multiple perspectives. Privileges were also incorporated in the institutional fabric of military careers in imperial Europe. Officers of the imperial armies had a shared cultural code and even exchanged institutions of honours. Members of the affluent middle classes could also fall back on experiences of cultural consumption and personal friendships, which could be rekindled after the war. Those among them who produced written accounts of their experience were among the first generation of writers of the First World War who continued seeing the war from the point of view of ‘civil society’. Some of these authors did so while recognizing that their own armies had turned into perpetrators against civilians. In this sense human sympathy, patriotism, and cosmopolitanism were entangled in the writing of officer-intellectuals in ways that were quite different from the twenty-first-century historiography of the conflict.Footnote 5

Selfie with a periscope: the experience of imperial horizons

In one of his wartime photographs, we can see Count Kessler gazing at the horizon through a periscope.Footnote 6 This emblematic image of elite vision in the war might, anachronistically, be called a ‘selfie with a periscope’. It is a curious photograph because, in a real situation of danger, an observer would not be standing in an open field. It is the reflexive character of the photograph that is of interest here: this is not a photograph of an officer in action, but one of an officer in narcissistic contemplation. The photograph simulates contemplation as a form of military action, since he is engaged in strategic analysis of the horizon. Yet the ultimate objective of this work is to provide a flattering portrait of the seer, not to communicate what he can see. In the background, the newly entrenched frontiers between the German, the Russian, and the Austro-Hungarian empires, blend into a common horizon of uncertain expectations. But for Kessler, the military frontier becomes a horizon, as he stages himself in Romantic pose. This perspective was familiar to his European contemporaries from such works as Caspar David Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea (1808–10), which a French admirer had once praised for its capacity to convey tragedy in landscapes.Footnote 7 Like in Friedrich’s famous painting, in this wartime portrait, a monotonous landscape produces a mood and an expression, which traditional portraiture would have projected onto the face of the portrayed. Aside from inverting the relationship between the figure and the landscape, the portrait also deceives the viewers, who cannot see what the figure can see and are thus forced to think and imagine their perception in their own heads. Even more than Friedrich’s monk, Kessler enjoys the privilege of looking through a technical device onto a detail that remains unknown to the viewer of the photograph.

As Kessler noted in his war diary from the eastern front, the periscope view revealed an odd image of Galicia:

a farmer’s house, some three or four meters in front of it a trench occupied by the Austrians, and some thirty kilometres on the left […] a Russian shelter, from which Russians were walking in and out. On the adjacent field between the Austrian trench and the Russians, some forty meters wide, a small girl was grazing a herd of sheep. As we watched, one of our grenades hit the ground near the shelter, and we could see the Russians rushing out quickly.Footnote 8

The cold, cinematographic description of his own army’s destruction of military targets along with civilian lives was the very opposite of the kind of ‘flesh-witnessing’, which is so characteristic of the soldier experience in the Great War, including authors such as Ernst Jünger.Footnote 9 The meaning of the experience derives from detachment, not involvement. Moreover, the tragedy of this experience is not a national one, or associated with any one empire. Before the war, Kessler, who had served as director of the influential German Artists’ Union, promoted an idea of style in which there was no contrast between being a ‘good German’ and a ‘good European’.Footnote 10 This photograph revealed a new dimension to this statement, transposing it from the realm of conflicts over styles to the realm of military conflicts between the European societies.

It was the desire to capture a complex reality devoid of meaning that prompted another officer who found himself in Galicia, Viktor Shklovsky, to reach further into the reservoirs of European literary history for a narrative model. Like Kessler, Shklovsky had begun his military service in an imperial army – of Russia, in his case – but gradually developed doubts about the logic of empire, without, however, ever fully endorsing the logic of revolution.Footnote 11 Shklovsky narrated his entire experience of war on the Galician front in the tone of his favourite English-speaking author, Laurence Sterne. His path through the eastern front was a Sentimental Journey with echoes of Sterne’s celebrated Grand Tour to France and the continent. It was meaningless if goals were defined in terms of geographic horizons; in telling about his life, he was merely ‘turning himself into a prepared substance for the heirs’. Yet, this experience of the imperial periphery also reminded him that in literature, it was the peripheral genres that had made breakthroughs in literature: ‘New forms in art are created by the canonization of peripheral forms’, he argued, just as Pushkin had developed the genre of the private album into an art form, as the novel had developed from horror stories like Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and as modernist poetry drew inspiration from gypsy ballads.Footnote 12 In the same way, he hoped, the travelogue – particularly, his travelogue of a meaningless war on the periphery – would contribute to a new literary form, and a new way of thinking about literature. It did: it created the theory, which he described as ostranenie, or detachment.

To this day, historians refer to those parts of Europe which border on the eastern front and the nation states that flickered into and out of existence during the twentieth century as ‘borderlands’, as the locations of ‘vanished kingdoms’, as ‘half-forgotten Europe’, as ‘invented’ places, or even as ‘no-place’.Footnote 13 In fact, in all of its history, the geography, if not necessarily the languages and cultures of eastern Europe, has probably never been as well known as in the mid-twentieth century. The image of the East as a great unknown remained a shibboleth of the post-Enlightenment philosophes, a geographic metaphor for the separation between civilization and barbarism, between power and weakness, and, more recently, between primitive national freedom and the imperial domination of modern civilization.

Kessler had experienced the eastern front in the First World War in an ethnographic light that might also be familiar from accounts such as Winston Churchill’s Unknown War.Footnote 14 By contrast to the western front, the eastern and middle-eastern fronts required the use of more traditional elements in the organization of the army. Large distances had to be covered on uneven terrain, which required extensive uses of cavalry. In his letters, Kessler speculated about whether the former Pale of Settlement could be turned into a vassal empire of the Germans, to be ruled by a Jewish dynasty such as the Rothschild family.Footnote 15 The search for Europe’s internally colonized peoples, like the Jews and other eastern Europeans who looked exotic, drew artists and anthropologists to the area.Footnote 16 ‘Tomorrow I am going to the front to examine the battleground and collect details. I suggested sending Vogeler to accompany me so that he could make sketches’, Kessler remarked in his diary.Footnote 17 The painter Heinrich Vogeler (1872–1942) eventually emigrated to Soviet Russia in 1931, where he died in a labour camp because he was suspected of being a German ‘enemy’.Footnote 18

War ethnographies and travel literature were modes of thinking about military violence that had developed greatly on the basis of experiences of the eastern front. In the west, tear gas and shelling were the most prominent instruments of war; in the east, where large distances had to be covered and the ground was insecure, cavalry continued to be important, even though contemporaries also report aerial attacks using Zeppelins being a constant danger. Being on the eastern front required a much deeper sort of military intelligence. Confusion was everywhere: Czech nationalists with German names, Poles who thought of themselves as Lithuanians but were socialists at heart, and so on.Footnote 19 This was still true in the Second World War. During his service for British intelligence, acclaimed historian Hugh Seton-Watson remarked that people in Britain were ‘aware of the existence of Zulus and Malays, Maoris and Afridis’, but eastern Europe with its ‘unpronounceable names’ remained uncharted territory, ‘another world’, full of wild plains and forests.Footnote 20

At the same time, not all of the encounters on the eastern front were confusing. Particularly officers could rely on having a shared cultural code with others of the same status. As Robert Liddell, a war journalist for the prestigious illustrated journal Sphere, who had just recently moved from the western to the eastern front, recalled, ‘[o]fficers of good family almost invariably could speak French. So could almost every Pole I met, and almost every lady doctor. […] and certainly the soldiers from the Baltic Provinces spoke German as well as they spoke Russian; many, indeed spoke better’.Footnote 21 He recalled being greatly amused by the following anachronistic words of one Russian general Bielaiev: ‘My boot’, said the general, ‘was filled with the gore of my steed’. General Bielaiev, who had Scottish ancestors, had learnt most of his English by reading Sir Walter Scott. For the purposes of the job, the journalist Liddell served as an officer of the Russian army, travelling along the front line with the Red Cross trains. Even though English was rarely spoken in the Russian army, he could get by on the eastern front despite his relatively poor Russian: the Russian general even called Liddell his fellow countryman, referring to his own Scottish ancestry. The half-mystical eastern Europe, some of whose local cultures, such as that of the Carpathian mountains, were hardly known to western Europeans, became one of the topoi of the ‘war experience’ for German audiences at home, as for instance in the liberal Vossische Zeitung.Footnote 22

Social scientists also became interested in analysing and representing the various European ethnicities of the eastern front, as in the work of the anthropologist Sven Hedin, Eastwards! (Nach Osten!).Footnote 23 Hedin, who collected ethnographic observations of the peoples of Europe, was another civilian assigned to Kessler on the eastern front. Kessler, himself once a tourist in search of the exotic, followed Hedin’s activities as he was taking pictures of local churches. The last person to study the wooden architecture of Galicia had been Franz Ferdinand himself.Footnote 24 Work of ethnography in the eastern front was also produced by German and Russian writers and artists. Arnold Zweig, who worked in German propaganda, provided illustrations of the eastern European Jews. The modernist artists Natalya Goncharova and Marc Chagall also made exotic-looking ‘Jewish types’ the main protagonists of their paintings.Footnote 25 In German prisoner-of-war camps, the anthropologist Leo Frobenius and a team of linguists ‘worked’ with interned Indians, Caucasians, Central Asians, and Africans from the British, Russian, and French armies to compare their intellectual faculties with those of Europeans.Footnote 26 Just as embedded photographers have become the order of the day in present-day wars, during the First World War, what might be called ‘embedded war tourism’ attracted a number of journalists and other intellectuals to war zones.

The officer’s role provided opportunities for sentimental detachment thanks to privileged access to such devices as periscopes. Traditionally, the officer class had the advantage of riding on horseback. During the Great War, the horse, the earliest ‘technique’ of aristocratic detachment, was gradually replaced by the airship. Other devices of this kind included special weaponry as well as periscopes and cameras. The mechanisms of detachment were only available to the higher army ranks. They were not limited to technologies but included such practices as the use of embedded artists and journalists assigned to officers. All this enabled members of the officer class to remove themselves from the theatre of war itself, both psychologically and physically. Detachment was an institutionalized privilege.Footnote 27 Zeppelin airships not only opened up the privilege of being removed from the ground but also offered the freedom to transgress political borders. For the first two decades, flights were almost exclusively a privilege of the few.

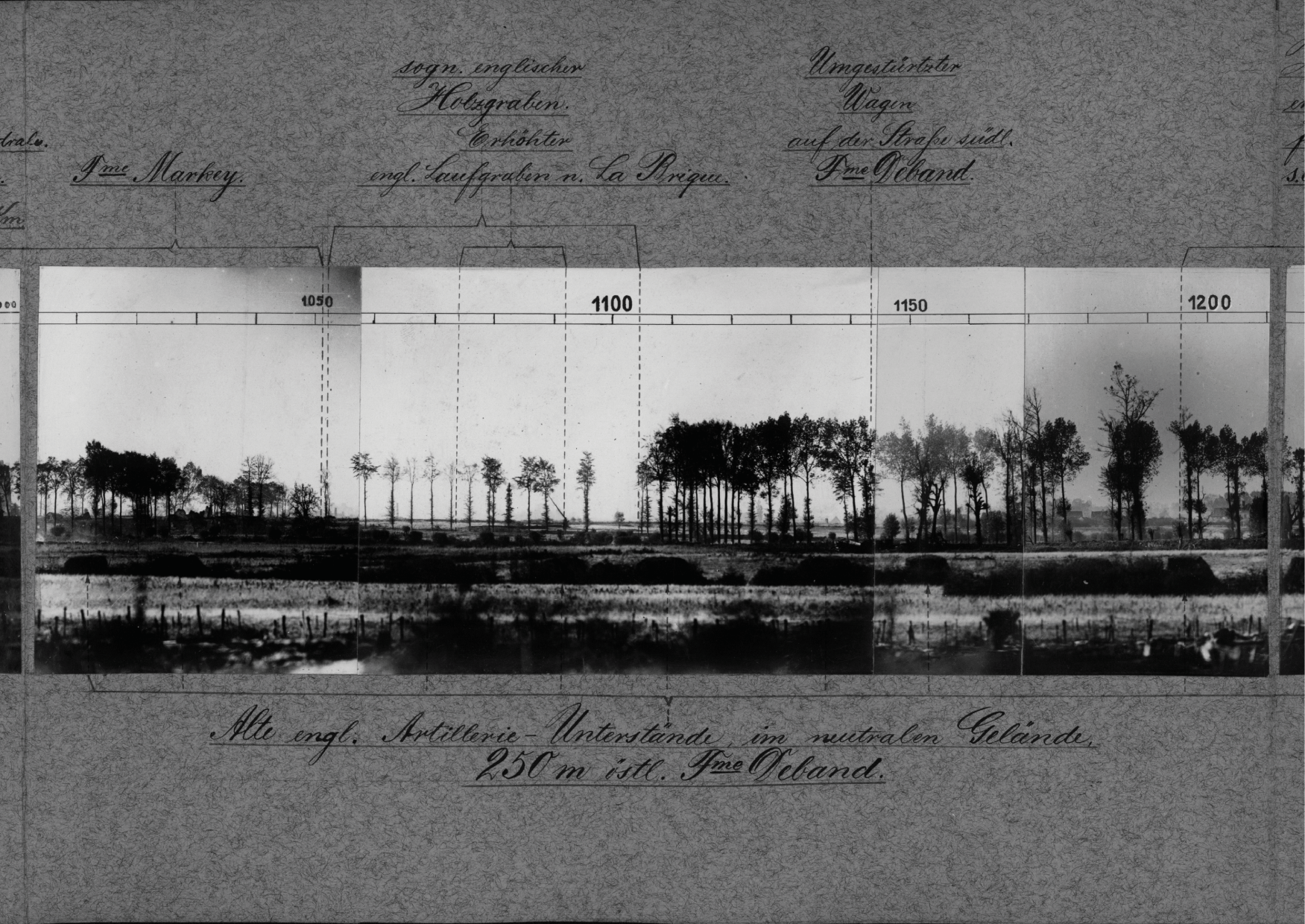

One of the first Zeppelin fleets was founded in a Saxon royal regiment. The Saxon nobleman Baron hans Hasso von Veltheim served during the war as a reconnaissance photographer. Veltheim was one of the first German enthusiasts of competitive hot-air ballooning, having joined the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale in 1905. Like the first British air minister, Sir Samuel Hoare, he was among the first generation of European elites to cross international borders by air.Footnote 28 He noted in his war diary that once he had flown as far as the imperial palace of Peterhof.Footnote 29 Before being deployed as First Officer of a Zeppelin airship, he had been responsible for photography on the Belgian front, for which he used unmanned tethered balloons as well as airplanes. Veltheim’s panorama shots of the Belgian theatre of war, which he kept in his personal archive, are visual testimonies of this European apocalypse [Fig. 6].

The writing of stylized war diaries like Shklovsky’s, the production of wartime self-portraits and the aesthetics of destruction in reconnaissance photography shot from the air: all these were forms of experiencing and representing horizons which invited reflections on conceptual frontiers. The meta-historical concepts of ‘experience’ and ‘expectation’, which the historian Reinhart Koselleck ascribed to the realm of theoretical reflections on horizons, were rooted in the immediate experiences of imperial horizons.Footnote 30

The cosmopolitans in the German Society of 1914

As John Maynard Keynes and George Curzon, two lovers of post-impressionist art, arrived in Paris in late March 1918 to bid at an auction of post-impressionist art, the German army was bombing Paris. Count Kessler, German attaché in Bern and another collector of post-impressionism, wrote in his diary: ‘War is a tough thing.’Footnote 31 He feared the lack of precision in bombing would damage not only Notre Dame and the Bibliothèque Nationale, which were key sites of his intellectual formation, but also the cemetery of Père Lachaise, where his father and his grandparents lay buried.

Kessler’s father had made a fortune in banking, connected to the railway business in Europe and Canada. The German emperor Wilhelm I ennobled him, according to family legend, as a sign of deference to the beauty of his Anglo-Irish wife, Alice Blosse-Lynch. The connection to Paris came from Kessler’s mother, who chose to be based there. It was her side of the family, of Anglo-Irish nobility, with a home in Partrey House in County Mayo, which also made Kessler aware of British imperial history of the British Empire. His grandfather had been a British minister in Baghdad during Mehmet Ali’s rule.Footnote 32 In March 1925, Kessler met distant Irish relatives in Paris who reported about the effects of the revolution in County Mayo; in the afternoon of the same day, he was engaged in debates of Count Richard Coudenhove’s plans for a pan-European federation with the German ambassador in France.Footnote 33 Kessler used his connections to British and French contemporaries to foster greater understanding between what he called his three ‘Fatherlands’. His autobiographic cosmopolitanism, his ‘English, German blood, English, German, French cultural heritage’ became a foundation for a particular form of internationalism.Footnote 34

Returning home after the war, he could barely recognize his own former self: that man from the Belle Epoque, who had commissioned from his French friend Aristide Maillol the sculpture of a cyclist, that furniture designed by Henry van de Velde, a Belgian, and commissioned the British artist Edward Gordon Craig to design illustrations for an edition of Shakespeare’s Hamlet – it was as if this man could no longer exist. In the aftermath of the war, Kessler began to view his background as a unique form of cultural capital. Before the war, friends called him the member of an anti-Wilhelmine ‘Fronde’ of good taste and anti-moralism.Footnote 35 As his views later radicalized, he earned himself the nickname of ‘Red Count’.

War was a traumatic experience for him. He had witnessed it on the western front, where he saw the German actions against civilians in Belgium first-hand, before being transferred east, which had shocked him no less. Kessler kept a diary, wrote letters, and engaged in discussions to cope with the traumatic experience of war. With his bibliophile Cranach press, which he had founded in 1913, inspired by William Morris’s Arts and Crafts movement, Kessler turned from a Prussian patriot into a patron of doubt.Footnote 36 He began to publish poetry from the trenches, including by communist poets – ‘Sulamith’ by Wieland Herzfelde and ‘Eroberung’ (‘Conquest’) by the expressionist poet Johannes R. Becher, the latter, in collaboration with the communist publisher Malik.Footnote 37 Kessler’s press was indeed ‘cosmopolitan’.Footnote 38 But he also sponsored communist artists like George Grosz and John Heartfield to do the design, often in collaboration with established German presses such as the Insel publishing house.Footnote 39 In 1921, he published in German War and Collapse. Select Letters from the Front on paper handcrafted with his old French friend Aristide Maillol, with a cover by Georg Grosz.Footnote 40

The war had blurred boundaries between nations and empires even more: ‘politics and cabaret’, ‘trenches, storming regiments, the dying, U-boats, Zeppelins’, ‘victories’, ‘pacifists’, and the ‘wild newspaper people’, Germany and its capital were surrounded by the least European of enemies, ‘Cossacks, Gurkhas, Chasseurs d’ Afrique, Bersaglieris, Cowboys’. If revolution did break out in this ‘complex organism’, Kessler thought it would be like the Day of Judgement. After all that the German troops had ‘lived through, carried out in Luttich, Brussels, Warsaw, Bucharest’ – Kessler referred to what is known in English as the ‘German outrages’ – these traumatic memories made it difficult to imagine a future for Germany.Footnote 41

In Germany, Kessler belonged to a network of German elites who came together to discuss policy. Founded just after the outbreak of the war, the German Society of 1914 was a political club that had been initiated by prominent figures in German public life. Among its members were people such as the diplomat Wilhelm Solf, the landowner and industrialist Guido Henckel von Donnersmarck, the writer Richard Dehmel, the industrialist Robert Bosch, the painter Lovis Corinth, the theatre director Max Reinhardt, and the notorious Pomeranian professor of Classics Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Möllendorff. The club represented German society as it had crystallized since the Franco-Prussian War and the founding of the German Reich in 1871, displaying the mutual influence between the feudal, the industrial, and the creative elites of German public life under the banner of German patriotism. Most of the German Society’s key members remained committed to German politics throughout their life. Walther Rathenau, the liberal technocrat, served as Prussia’s war supplies director, advocating the London air raids, which were carried out from Zeppelin airships, and later became foreign minister until his assassination by a right-wing paramilitary group in 1922; Hjalmar Schacht, the banker, directed German economic policy under the Weimar Republic and the Nazis up to 1937; the painters Liebermann and Corinth came to shape the public image of the German landscape with their plein-air paintings of Brandenburg and Pomeranian lakes; the publishers Samuel Fischer and Anton Kipppenberg became representatives of the classics of German literature as such. Among the club’s youngest members was the liberal Theodor Heuss, who would live to become the first German president of the Federal Republic after the Second World War.

But not all Germans in this society were patriots or defenders of its military strategy in the war. The philosopher Hermann Keyserling was another person Kessler met there on a regular basis. One of his first political publications was an article published in English titled ‘A Philosopher’s View of the War’. There, he criticized the nationalist sentiments fuelling the war from both a Christian and a universalist perspective.Footnote 42 Keyserling protested against the war as ‘Russian citizen’ and a pacifist.Footnote 43 He published this work in the journal associated with the British Hibbert Trust.Footnote 44 Founded in the previous century by Robert Hibbert, a wealthy Bloomsbury aristocrat who made his money in the Jamaican slave trade, it represented the ecumenical and largely pacifist values of the Unitarian Church. It regularly invited contributions on general topics discussed from a spiritual point of view. Among its contributors were the French historian Ernest Renan, the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, and the German doctor and intellectual Albert Schweitzer.

When his friend, the sociologist Georg Simmel, heard about this, he warned Keyserling that he may have to cease their friendship if rumours about Keyserling’s anti-German sentiments turned out to be true.Footnote 45 A subject of the Russian Empire, Keyserling had not been drafted into the army due to an earlier duel injury. By the end of the war, he was caught by the revolution on his estate in Russia’s province of Courland. He spent this time working on an essay he titled Bolshevism or the Aristocracy of the Future. Between 1918 and 1920, he later remarked, ‘centuries had passed’.Footnote 46 He had seen previous revolutions, like the one in 1905, when his estate was burnt, and he also witnessed a revolution in China and elsewhere. But unlike then, he saw that the old empires could now no longer hold on to their prestige. Among the voices heard at Brest-Litovsk, Keyserling remarked, it was not that of the old Prussian or Austrian diplomats but that of the Bolshevik Leon Trotsky that won the game. Much to the confusion of his contemporaries, particularly of similar social background, he thought that listening to Trotsky was necessary in order to make room for a new, truly European aristocracy of the future.Footnote 47

Defending himself against charges of anti-German propaganda during the First World War, Keyserling thought that idea of Germany could only survive as a ‘supranational’ idea: ‘in the interrelated and correlated Europe of tomorrow, the spiritual root of that which once blossomed forth in the form of the Holy Roman Empire of German nationality – the supranational European idea – will once again become the determinant factor of history, in a greater, more expansive form, conforming to the spirit of the time’.Footnote 48

The other sealed train: chivalry in the Polish revolution

In early November 1918, the German government appointed Kessler as a German envoy. His task was to release the leader of the Polish legion, Jozef Piłsudski, from Magdeburg fortress, where he was held prisoner during the war. Pilsudski had been granted the right to lead a Polish legion within the Habsburg army, but as a Polish nationalist, he had been unwelcome to the Austrians. Now that it was clear that Austria-Hungary would not be resurrected, Germany had other ways of making use of this prisoner. At the end of the war, the legion became the nucleus of a Polish nation state.Footnote 49 As early as 1915, German officers had approached Piłsudski in Volhynia, soliciting his opinions on the future of eastern and central Europe.Footnote 50 At this point, Piłsudski’s Polish Legion formed part of the multinational Habsburg army. At the same time, it was increasingly taking up the powers and duties of a future Polish state; as a representative of the future Polish nation, Piłsudski refused to give an oath of allegiance to the central powers and was therefore taken prisoner by the German imperial army.Footnote 51

Railway networks had been crucial elements of European imperial growth as well as inter-imperial financial networks in the nineteenth century. While such projects as the Baghdad railway line brought together private investors across different European states and beyond, they remained publicly associated with the imperial Great Game between the European nations.Footnote 52 But in the course of the war, trains also gained a key role in Europe’s post-imperial transformation. During the war, members of the German diplomatic staff worked together with Swiss politicians to facilitate the arrival of Lenin and his entourage in Russia to promote revolution there in April 1917.Footnote 53 Immediately after the war, Kessler was involved in a similar, if more modest, undertaking. It paralleled Lenin’s German-sponsored passage to Russia (the preparation of which Kessler also witnessed in Bern) insofar as the German executive powers had asked Kessler personally to escort Piłsudski from Magdeburg to Warsaw in a special sealed train.Footnote 54

Kessler described this episode in one of several small memoirs that he would publish to great acclaim in the liberal German journal Die Neue Rundschau. The lens through which he chose to interpret this situation was the persistence of chivalric values at a time of revolution. When Kessler personally met Piłsudski upon his release from Magdeburg prison, he handed him his sword. Together, they travelled back to Warsaw on a luxurious personal train, which took off from Bahnhof Friedrichstraße and was equipped to the standards of an ‘American billionaire’. Both the aristocratic and the oligarchic elements in this handover of power contrasted markedly with the executive powers that had entrusted Kessler with this task as the fate of the revolutionaries in Germany itself was far from clear.Footnote 55

In December 1918, Kessler oversaw the withdrawal of German troops from Poland, and Poland established a nationalist government with closer ties to France than to Germany.Footnote 56 Kessler later recalled that the Polish leader gave him ‘an oral declaration in the form of a word of honour because I had refused to demand a written declaration from him’ that he would not claim German territory.Footnote 57 Piłsudski and Kessler probably shared certain characteristics, such as their background from lower nobility, the ‘Prussian’ sense of military honour, and a Mazzinian cosmopolitan nationalism.Footnote 58 Kessler saw it as the duty of persons of higher standing, such as Piłsudski and himself, ‘to lead our nations out of their old animosity into a new friendship’.Footnote 59 In the Polish, German, Dutch, British, and American press, rumours were circulating in December 1918 that Kessler was providing support for a ‘Bolshevik’ uprising in Poland using government money.Footnote 60 In fact, however, Piłsudski assured him that he was pursuing a policy of social democracy aimed at steering clear of Bolshevism. Indeed, Kessler dismissed all allegations of ‘Bolshevism’ as ridiculous, even though he indeed had sympathy for the revolutionary councils in Germany and Poland (Lodz) and the Caesarist social democracy of Piłsudski.Footnote 61

Like many others in his position, Kessler had suffered a nervous breakdown in the course of his service on the eastern front. He was allowed to retire from active service and was given a unique position: to head the department for Cultural Propaganda in secret, in Switzerland. At this point, Kessler could deploy his expertise in the cultural internationalism of the pre-war era to serve a more concrete goal. As he put it:

Now I have finally reached the actual project of my life: to forge Europe together practically at the highest level. Before the war, I had tried it on the much too thin and fragile level of culture; now we can turn to the foundations. May it be a good omen that my appointment occurs on a day when perhaps through Germany’s acceptance, a new era of peace will start.Footnote 62

Before the war, Kessler’s exposure to debates about national styles and tragic landscapes had been restricted to the realm of aesthetic contemplation. As a result of his wartime position, Kessler obtained a new perspective on these conceptual frontiers, a transformation that was facilitated not least because he was empowered to cross established frontlines. His experience of the German and the Polish post-imperial transformation made these revolutions appear like personal affairs, in which the populations of these states became mere secondary agents on the historical stage. The eastern European horizon became a visual concept that was highly suited for expressing his ambivalent position. Like others in his circle, Kessler recognized his complicity with German military violence in Belgium and in eastern Europe, but stopped short of endorsing the more radical form of the revolutions in Germany and Europe. Instead, he refashioned his long-standing, initially purely aesthetic critique of national chauvinism in Germany’s imperial past into a new, liberal form of internationalism.Footnote 63

Imperial regiments after empire

With his transformation from a loyal officer of one of Prussia’s elite army units into a sceptical and self-doubting witness of a European civil war, Kessler’s voice was in the minority, but far from singular amidst a growing sound of disenchanted Europeans. To understand the genealogy of this disenchantment, we need to take into account the psychological effects of war trauma on the self-perception of the military elites in the war. As already discussed, members of elite officer corps were well positioned to understand the theatre of war not least due to having access to privileged forms of experience, such as airplanes. Being cavalier about war, and having a horse in wartime, are related not just linguistically. According to one historian, the cavalry was a ‘cosmopolitan institution, and based upon the same general principles throughout Europe’. As a British historian commissioned by the Russian Tsar Alexander II to write a history of chivalry had put it, the privilege of service with the horse, or chivalry, ‘was without doubt one of the most important causes of the elevation of society from barbarism to civilisation’.Footnote 64 In most European imperial armies of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, officers generally came from aristocratic families and were educated at corresponding institutions, including the French Cadets schools, which emerged in the seventeenth century; the Cadet schools and the Theresianum academy in Vienna; Lichterfelde in Potsdam; and Sandhurst in Britain.

Historically, the imperial armies remained connected with each other through mutual partnerships. For instance, the European royal guards had a tradition of conferring honorary leadership to monarchs ruling a different state. For instance, the first West Prussian Ulan Guard regiment was formally under the leadership of three Romanoffs between 1859 and 1901, even though the commanding officers were Prussian and not Russian subjects. The regiment was even named ‘Kaiser Alexander III von Russland’, after the Russian tsar. From 1896 to the outbreak of the First World War, Habsburg emperor Franz Josef was the formal commander-in-chief of a British regiment, the 1st King’s Dragoon Guards. The Austrian Radetzky March is still its official song. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, some British regiments consisted entirely of German auxiliaries, including both officers and soldiers.Footnote 65 The French army had foreign regiments (not to be confused with the Foreign Legion) serving under its banners from the ancien régime to Napoleonic times. Before the revolution, there were Swiss, German (particularly, from Saxony-Anhalt and Nassau), Irish and Scottish, and Wallonian regiments serving under the French king. The practice of renting out mercenaries to foreign armies, which came to be associated mostly with the Swiss mercenaries and with several German principalities, included non-European troops – the Napoleonic army had Circassian and Egyptian (‘Mameluk’) regiments, and subsequent French armies had troops from Senegal.Footnote 66

Cross-imperial connections among the elites transcended the boundaries of Europe. One of the last cavalry regiments of the British army, which was deployed in the capture of Jerusalem during the First World War, had been co-founded by a former maharajah who had been dispossessed under the Raj as a child. Prince Duleep-Singh had briefly occupied the throne in one of India’s richest states, the Punjab, when an uprising against the British Raj began. The uprising was put down, but with the insurgents, the British army removed the maharajah himself. Installed in Norfolk with a generous pension but no power, the young former maharajah began to live the life of an English gentleman. He assembled, among other things, a collection of portraits of East Anglian dignitaries in Thetford Forest. The Norfolk Yeomanry, which he co-founded, was a volunteer cavalry, which fought for the British war effort at Gallipoli, and later participated in the conquest of Jerusalem before finishing the war on the western front.Footnote 67

The dismantling of the imperial armies of Austria-Hungary and Germany under the Versailles treaty called into question the special hierarchical privileges of officers, which formed the very heart of the old armies.Footnote 68 The Habsburg Empire’s officer corps was almost a caste, even though it had gradually become more permeable in the last decades of its existence.Footnote 69 The same can be said of the other German officer corps, above all, that of Prussia.Footnote 70 Even though changes in legislation following the reforms of the 1820s meant that new ennoblements created new military nobilities in all these states, access to officer posts had been strictly regulated and limited to specific trusted families. Those who trained with the cadet school were subject to harsh discipline, as described in some of the classical works of Austrian literature in which the cadet features prominently.

Whilst being strictly hierarchical by class, the ranks of the Habsburg imperial army effectively moderated the political impact factor of their subjects’ ethnic and regional identities. Looked at horizontally, the Habsburg army especially was a thoroughly multilingual and, though to a lesser extent, also a multi-ethnic community. By contrast, the German imperial army, which had emerged, like the German empire, in 1870/71, after the Franco-Prussian War, gave Prussia de facto a leading role among the formally equal units of the German princes.Footnote 71 This difference was crucial for the structure of post-imperial conversion among the post-imperial officers.

In Austria, as Istvan Deák has emphasized, the disappearance of the Emperor as a unifying figure encouraged former career officers to seek a career in the national successor-states of the old empire.Footnote 72 For officers of the Polish and Czechoslovak legions, there was no contradiction between endorsing revolution in Austria, which gave their nations a long-sought form of sovereignty, and joining anti-Bolshevik military campaigns in the Russian Civil War and elsewhere in eastern Europe. By contrast, for the armies of the German states, the idea of a greater Germany continued to provide a source of aspirations for the future. Moreover, anti-Habsburg German nationalists like Adolf Hitler, who had already served in the Bavarian instead of the Habsburg armies in the war, now saw Germany and not Austria as their primary cadre of reference.Footnote 73

Former officers had to adjust to an uncertain future in Germany, too: its army was now severely reduced in size after the Versailles peace settlement. But unlike Austria, Germany lost not more than one-seventh of its territory in the war, and thus remained a significant force in Europe. As critics of institutions such as the Prussian cadet training at Lichterfelde have suggested, such institutions produced forms of obedience to authority, which were inimical to a society of equals.Footnote 74 It has been a long-standing belief particularly among émigrés from Nazi Germany and Austria that radicalization among the disenchanted soldiers and officers had been one of the root causes of Germany’s path to Nazism. The sociologist Norbert Elias provided the most succinct portrait of the army as a key case study for the decline of honour in German society and its descent into dehumanization.Footnote 75 Yet more recently, historians have highlighted that traumatic war experience and the abolition of privilege also produced less reactionary forms of doubt, and even served as the foundation for pro-republican beliefs.Footnote 76 A former officer of the Bavarian army, Franz Carl Endres, turned into a sociologist and remarked in the journal Archiv für Sozialwissenschaften und Sozialpolitik that the Prussian army had always been in the service of the Hohenzollern dynasty more than it had served the German people.Footnote 77 He thought that a future army had to develop other forms of commitment. The left-leaning magazine Die Weltbühne even had a regular column appearing throughout the year 1917, entitled ‘From a field officer’, which supplied ironic remarks on the deconstruction of the officer.Footnote 78

Adjustment to the post-war world saw the former officers take on a variety of social roles, particularly in the wake of social unrest in Germany during the winter of 1918/19. What is most widely known now is the emergence of paramilitary groups, the so-called Freikorps, which took it upon themselves to fight against revolutionary movements in the German cities. This was not only done out of conviction but sometimes for pecuniary considerations as well. Baron Veltheim, for instance, after his service for the Saxon royal army, claimed that he joined a freecorps unit in Berlin to fight the ‘red’ revolutions there in January 1918 because he was short of money. In this way, the war continued, after only a brief intermission, in the form of a civil war on the streets of Berlin, including ‘Alexanderplatz, the police prefecture, Reichstag, Brandenburger Tor’ and other locations. The fighting parties, which he called the ‘white and the red’, were equally repulsive to him. But he was particularly shocked by the refusal of his comrades to have sympathy for the ‘wishes, feelings, and thoughts’ of the ‘revolutionary workers’. Whenever he tried to prevent what he called ‘excessive violence’ against them, he was suspected of being a ‘spy of the revolution’.Footnote 79

Another example of a freecorps officer with more conviction for the cause of fighting the revolution was the Prussian officer Ernst von Salomon. He was convicted of murdering the German foreign minister Walther Rathenau and served a prison sentence in the Weimar Republic, during which he wrote a book about the times.Footnote 80 It is a fictionalized autobiography, in which his authorial self asks, ‘Was it worthwhile to attack these people? No, it was not. We had become superfluous […]. All over! Finis – exeunt omnes. The world wanted time in which to rot comfortably.’Footnote 81

It is noteworthy that the paramilitary officers of the former armies turned to writing to make sense of their conversion as much as those who became pacifists or critics of military culture. The writer Fritz von Unruh came from a long lineage of Prussian officers. Around the turn of the century, his father had been the commander of Königsberg Castle in East Prussia. In his autobiographical novels and plays, however, he usually adopted the perspective either of plain cadets or of civilians: one of his protagonists is the poet Kaspar Friedrich Uhle.Footnote 82 Unruh consciously established an intellectual affinity between himself and an earlier Romantic disenchanted with Prussian military traditions, Heinrich von Kleist, whose Prince of Homburg was a modern-day Hamlet who consciously refused to exercise his duty as a Prussian officer. Unruh’s relative Joseph von Unruh (or Józef Unrug, as he was known in Poland) served as an officer of a Prussian regiment in the First World War, but joined the newly formed Polish legion after the war, and in the Nazi era was an agent for the Polish government in exile in Britain.

Other former career officers became so radicalized that they abandoned their aristocratic identity altogether. The most familiar examples of such conversions belong to the history of the Third Reich. Prior to the abolition of the republican constitution in Germany, the SA, one of the paramilitary organizations which was initially in conflict with the Nazi party, had been particularly successful in recruiting former officers. The historian Karl-Dietrich Bracher called them déclassé, yet, at the time when this generation of officers served in the armies, the German aristocracy was no longer a class but merely a social configuration. In terms of class, they had long merged with the bourgeoisie.Footnote 83 By the time of the Second World War, a number of the old German officers in the post-imperial successor states also gravitated to the Wehrmacht, particularly in eastern Europe.Footnote 84

Yes, this sort of aristocratic conversion at a time of institutional disorientation was also a phenomenon for the political left in interwar Germany. A particularly spectacular case was that of a Saxon aristocrat who first adopted a fictional alter ego and a pseudonym, and then turned his pseudonym into his new proper name. The officer Arnold Vieth von Golßenau had served in a regiment of the Saxon Royal Guards during the war. Yet his own fictionalized account of the Great War, an interwar bestseller that was translated into English and French, was written from the perspective of an infantry man because, as he later recalled, it was ‘not the officer who had impressed me with his actions on the front, but the nameless soldier’.Footnote 85 Writing the novel, which quickly became a bestseller rivalling Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front in popularity, he increasingly identified with the protagonist of the experiences he had himself created. He became the protagonist, Ludwig Renn. As he later recalled, he himself ‘lived through this time as an officer, a man with many traditions’.Footnote 86 After the war, Ludwig Renn, as the former aristocrat now officially called himself, joined the communist party, became a leading member of the republican troops in the Spanish Civil War, emigrated to Mexico with the anti-Nazi Committee for a Free Germany. After the end of the Second World War and the division of Germany, he eventually returned to what was now the GDR to become a professor of anthropology in Jena. This is perhaps the starkest example of the capacity for detachment particularly prevalent among the officer intellectuals of the First World War.Footnote 87 Yet Renn’s case was far from singular. Other examples of elite officers who became active on the international Left between the wars and in the Second World War included Count Rolf Reventlow, the son of a famous Munich Bohémienne, who was a journalist in the Munich republic and later joined the international brigades in Spain.Footnote 88

In the light of the scholarship on Germany in the Third Reich, it is easy to overlook that in the interwar period, the German aristocratic officer could impersonate the idea of international reconciliation through the solidarity of elites, as it did in Jean Renoir’s now classic film of 1937, The Grand Illusion. Its title derives from a book by Norman Angell, a British economist, on the futility of war, called The Great Illusion, dating back to 1910, for which the author won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1933.Footnote 89 The book centres on the futility of the Anglo-German arms race and has no special interest in the military elites, instead focusing on the idea of friendship between societies. But in the film, this abstract notion of friendship is made literal through the link between aristocratic aviators from France, which enables the viewer to draw Angell’s conclusion emotionally. When the aristocrats in the film voice their own feeling of futility, they present a kind of first-person view of imperial decline. But Renoir did not invent this new social role for them. The officers-turned-intellectuals had already prepared it.Footnote 90

For officers and members of internationally connected aristocratic families, war was not merely a sphere of extreme physical violence but also a field of symbolic interaction. The right of these officers to use horses and later airships in battle, literally and figuratively elevating their perspective, facilitated detachment from the experience of war as a struggle between nations or empires.

The invention of tragic landscapes

In 1923, Kessler was enjoying a picnic in the Berkshire Hills of Massachusetts. He was invited there to speak of Germany’s place in Europe, and the constitutional changes which had occurred under the republic.Footnote 91 His hosts, men and women who had served in the First World War either as officers or as nurses, shared their memories of this still recent time. The beauty of nature reminded them of the Carpathian Mountains on the eastern front, while the ‘moral indifference’ of nature itself brought to mind the ‘human atrocities’ they had witnessed. Kessler remarked that there was a great feeling of mutually shared ‘humanity’ in these conversations.Footnote 92 Prior to the war, Kessler had been trained to believe, with Wilhelm Wundt, that landscapes evoked above all national sentiments and attachments. He now grew convinced that the ‘meaning’ of landscape was either tragic universalism or utter indifference to human identities. There was no ethical link between the shape or the beauty of a landscape and the actions and sentiments of the people taking root in it. For people of Kessler’s circle, it was possible to think of the western front in terms of an affective geography, as a ‘“tragic region” to be turned into a holy site for Europe as a whole and not for any one nation in particular, to draw pilgrimages each year from all parts of the Earth to condemn war and to sanctify peace, to show their devotion in front of this great, wounded cathedral!’Footnote 93

Publications like Michelin’s Guides to Postwar Europe, published between 1919 and 1922, used images of war ruins on the western front in order to create a new type of mass tourism, which still exists today. As the introduction to the 1919 edition put it, ‘ruins are more impressive when coupled with a knowledge of their origin and destruction’.Footnote 94 Yet until Franco-German cooperation developed joint commemoration events for the Great War in the 1980s, public memory of these sites remained tinted with national colours.

The idea of perceiving an entire landscape of war as ‘tragic’ required a cosmopolitan perspective. In the 1920s, psychiatrists dealing with cases of war trauma observed that certain cases of what today would be called post-traumatic stress disorder were much more likely to occur among the higher ranks. Some even ventured to suggest, as Robert Graves did, that officers had a ‘more nervous’ time than men, confirming some findings of new approaches to the sociology of war based on statistics from the Franco-Prussian War as well as the Great War.Footnote 95 He recalled a time when, before the war, he had been visiting his German relatives, the Rankes; at their house, presciently called ‘Begone, anger’, ‘there was a store for corn, apples, and other farm produce; and up here my cousin Wilhelm – later shot down in an air battle by a school-fellow of mine – used to lie for hours picking off mice with an air-gun’.Footnote 96

Having access to education and technology gave elite participants in the war more devices through which to gain a more distant view of the war process. They could also rekindle their social connections after the war was over. It was easier for those who previously had social experiences in common. In the mid-1930s, Kessler and Graves became neighbours in exile on the Balearic island of Mallorca. Graves’s exile from Britain was voluntary: he spent this time to rewrite his version of the Greek myths. Kessler, by then a refugee from Nazi Germany, wrote his memoirs on the island, which allow us to contextualize in social perspective how former German elites contributed to a new transnational sensibility after the war.