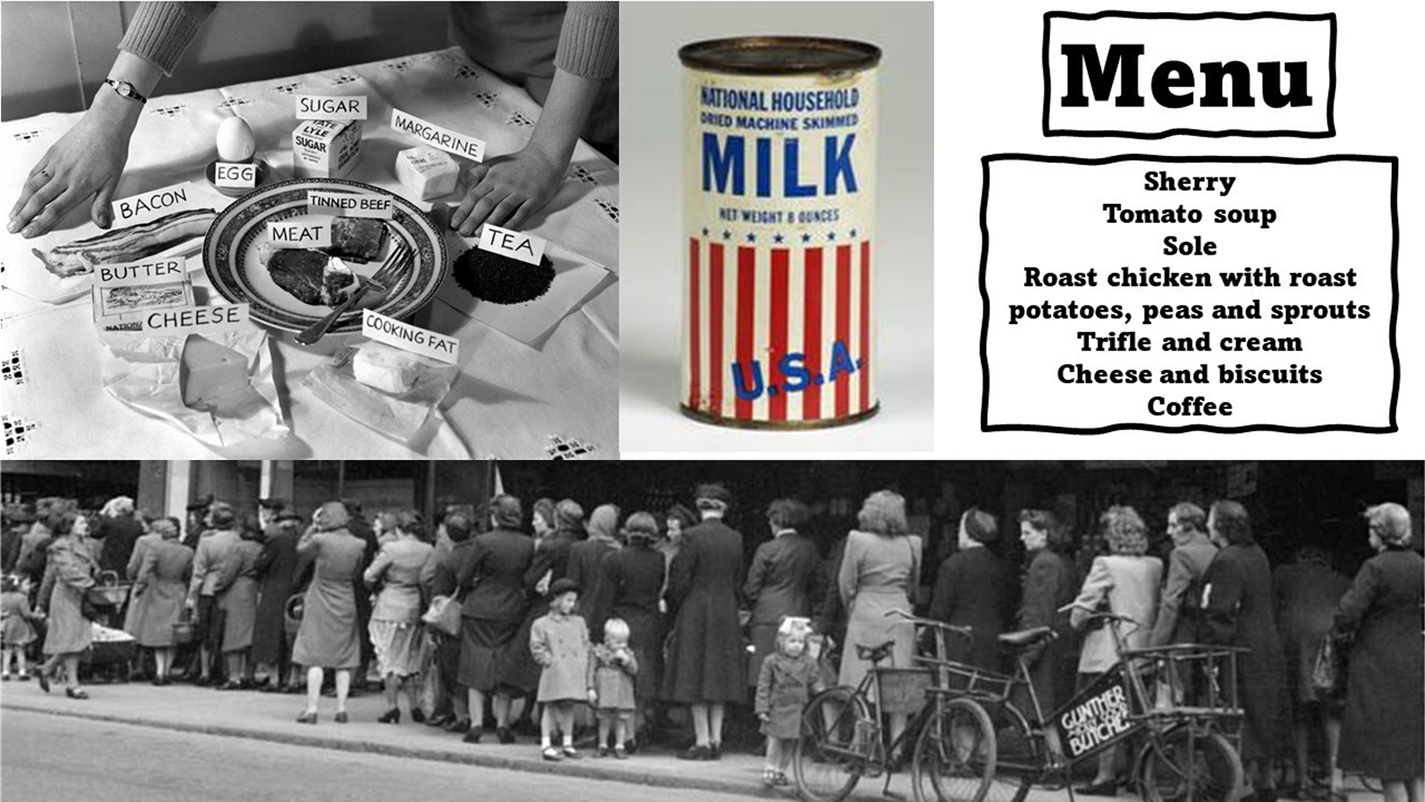

C'est la soupe qui fait le soldat. Loosely translated as ‘an army marches on its stomach’ and attributed variously to Frederick the Great and Napoleon Bonaparte, this expression exemplifies the importance attributed to a nutritious diet by the dynastic leaders of the 18th century, a policy which led directly to the invention of food canning, amongst other things. The Iron Rations enjoyed by Wehrmacht troops as well as the Nazi Hunger Plan whereby food would be seized from Soviet citizens for the benefit of Germans are further evidence of the need, during times of conflict or challenge, to ensure ample availability of calories and protein. This is something which was far from assured in very many countries during the post-war rationing years, and still is for a large proportion of our global population (although that is another story). I can personally still remember some of the products and policies (national baby milk formula, free school milk) that were available in the UK early in the second half of the twentieth century, but more than that I remember the importance and common sense that was applied to diet by my elders and peers. Figure 1 shows (clockwise from top left), the weekly allowance of rationed foodstuffs for one person, milk powder imported from the USA, the ‘fantasy menu’ chosen by Gallup survey respondents and a food queue, all from the UK in the late 1940s. Dairy products figure prominently, although knowledge level is also apparent from the fact that the queue was for fruit and vegetables. Fast forward 30 years to the start of my research career and my discovery that new friends and neighbours knew little of the ‘exotic’ vegetables (courgette, for instance) I offered from my allotment but were happy to reciprocate with sweets for the kids, thus helping to explain the all-too familiar site of skinny adults walking down our local High Street accompanied by obese offspring. Two words are probably sufficient to explain what had happened to food: Cheap and Fast. In the post-war years, Cheap Food policies adopted by governments in developed countries essentially following our opening aphorism led to a major reduction in the proportion of earnings spent on food. Fast Food invented and aggressively marketed by multinational corporations led (arguably) to the belief that food was simply ‘there’ and did not really need to be thought about, Just Eaten (the capitalization is deliberate, as you will probably understand!) The effect has been to turn the response to a challenge (plentiful food) into the challenge itself (obesity is now thought to be a bigger threat to health than smoking, at least in the UK). Globally, we are the first generation more likely to die as a result of lifestyle choices than infectious disease. This statement is taken from the Terms of Reference for The National Food Strategy, a major independent report into all aspects of the UK food industry undertaken for the UK Government and led by the restauranter Henry Dimbleby. Commissioned in 2019, the Strategy represents the first major reexamination of UK food policy since the Agriculture Act of 1947 and has now appeared in two parts published last year and last month. It is somewhat ironic that the process was overtaken by the most impactful infectious pandemic modern society has ever seen, such that the first objective for future actions emerged as ‘Escape the junk food cycle to protect the NHS’ (Protect the NHS was the COVID-19 watchword in the UK). The statement regarding global deaths was not substantiated and, whilst it is certainly true that diet-related illness is a major contributor to untimely death, I would question the use of the phrase lifestyle choices; where out-and-out malnutrition or starvation is concerned, it is not a choice. This is the fundamental difference as I see it. In the developed world we do, generally, have the choice to eat healthily, but many of us do not make it. Why is that? It can hardly be attributed to a lack of information; as adults we are bombarded with healthy eating advice, probably to the point where we simply stop listening to it. Much of that information ‘fingers’ individual foods as inevitably bad whilst extolling the virtues of others as ‘super-foods’. This is simultaneously over-simplistic (our digestive system is both incredibly complex and supremely adapted to deal perfectly well with a wide range of foods) and over-prescriptive; is it really impossible to eat well without adopting a ‘…tarian’ (flexi…/vege…/pesce… and so onFootnote 1) diet? Has ‘balanced diet’ lost its meaning? Or are we actually addressing the wrong question? Is it what we eat that is unhealthy, or how much of it we eat? The adoption of dairy alternatives by major dairy companies (ARLA's Jörd oatmilk, for instance) and the repositioning of food giants such as Unilever towards meat alternatives would suggest that multinational corporations are much more interested in simply selling more, irrespective of what. My worry is that the average consumer is so bewildered by which foods are or are not ‘healthy’ that they forget the most important message, namely that excess is unhealthy. In that regard, energy-dense foods inevitably risk pushing consumers into the ‘excess’ category quicker than others, so how good are we at identifying energetic contents? Given the rather similar appearance and formulation of the cereal and fruit/nut ‘energy bars’ and ‘protein bars’ increasingly found on supermarket shelves, should consumers be forgiven for thinking, mistakenly, that protein is somewhat synonymous with calorie? This is not the first Editorial to mention the National Food Strategy: Judy Buttriss (Director General of the British Nutrition Foundation) wrote hers two years ago (Buttriss, Reference Buttriss2019). She stressed the importance of education and food literacy and I would concur wholeheartedly with that view. If we as consumers are to make healthy choices then I believe that we need knowledge more than information, and the best way forward is for that knowledge to be imparted at an early age by education systems, parents and media. The messages must be simple so that they can be understood by all, and balanced diet in moderation could make a good starting point. In stressing the impact of socioeconomic inequality (the less well-off generally eat less healthily) the National Food Strategy made the following observation: ‘Education and willpower are not enough. We cannot escape this vicious circle without rebalancing the financial incentives within the food system’. By which they mean that healthy foods tend to cost more. It is a gross oversimplification to suggest that ‘healthy’ equates with ‘fruit and veg’ but that is the basis of this argument, so why should fruit and vegetables be seen as expensive? Part of the reason for the queue shown in the Figure was not a desire to be healthy, simply a need to eat. Fruit and vegetables were never rationed in post-war Britain, and home-grown produce was plentiful; rural households would grow more than 90% of their needs in gardens or allotments (community-owned vegetable plots rented at low cost to local citizens). It is refreshing to report that the Strategy does advocate greater emphasis on education (an ‘Eat and Learn’ initiative for schools) but I am equally heartened by the news that demand for allotments has increased by 300% in the last year. Probably mainly a consequence of COVID-19 lockdown, nevertheless a sensible decision by central Government to exempt them, and one which hopefully will lead to more people realizing that fruit and vegetables need not be expensive. The Strategy runs to more than 400 pages and makes a total of 14 Recommendations to Government organized in four categories, so forgive me if I do not analyse it in detail. The recommendation that was immediately picked up by the media and almost as quickly rejected by the Prime Minister was to impose a tax on sugar and salt bought commercially by food processors. This ‘stick’ was seen by policymakers as likely to increase food inequality, exactly the opposite of what the authors intended it to do, so the governmental Cheap Food policy still holds sway. The Strategy is heavily focused on reduced consumption of animal-derived foods and proposes various measures (‘carrots’) for subsidizing the cost of fruit and vegetables to help achieve this, some of which have already been adopted. Disappointingly, the nutritional value of milk is never mentioned and almost every mention of dairy is in the context of being part of a supposed meat and dairy ‘problem’ (although the increased protein-generating efficiency of dairy cattle vs. beef is recognized). The Strategy has many good points and is certainly well-intentioned, but I fear that it has tried to steer a middle path between common sense-based superficiality and science-based rigour and has failed to properly capture either, ending up with too many recommendations that are all overly detailed and complex. Perhaps the lesson of 1947 was that simplicity has virtue; we needed more food and that was delivered. Now my simple message would be that we need consumers to make the better choice of a balanced diet consumed in moderation. The UK Government is committed to responding with a policy White Paper within six months, which will give an opportunity for a more detailed analysis in this Journal, focused on how dairy can contribute to fulfilling that need.

Fig. 1. The Figure shows (clockwise from top left), the weekly allowance of rationed foodstuffs for one person, milk powder imported from the USA, the ‘fantasy menu’ chosen by Gallup survey respondents and a food queue, all from the UK in the late 1940s.