The United Nations1 (1999) defines terrorism as “any act that seeks to cause death or serious harm to a civilian or any other individual who is not playing an active role in hostilities in a situation of armed conflict, when the purpose of said act is to intimidate the population or to force an organization or government to carry out or omit an action” (Article 2 of the International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism). On March 11, 2004, Madrid suffered one of the worst terrorist attacks in the history of Spain. Multiple backpacks full of explosives detonated inside 4 trains in a jihadist attack, leaving nearly 200 dead and almost 2,000 injured.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the most prevalent mental disorder associated with terrorist attacks (García-Vera & Sanz, Reference García-Vera, Sanz and del Real Alcalá2017). Recent data suggest that 33% to 39% of direct victims will develop PTSD. 17% to 29% of indirect victims (especially family and friends) may also develop this disorder. While it is true that PTSD symptoms tend to mitigate over time, direct victims will continue to show a prevalence of 15% to 26% up to seven years after the traumatic events (García-Vera et al., Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Gutiérrez2016). Albeit the most prevalent, PTSD is not the only disorder present in victims. They may also show other diagnoses, such as depression, generalized anxiety, panic attacks and agoraphobia (Conejo-Galindo et al., Reference Conejo-Galindo, Medina, Fraguas, Terán, Sainz-Cortón and Arango2007).

However, the long-term impact of terrorist attacks goes beyond diagnosable disorders, and is reflected in physical and psychological health, as well as in reported levels of well-being or life satisfaction (Bromet et al., Reference Bromet, Hobbs, Clouston, Gonzalez, Kotov and Luft2016). One of the reasons for the relative lack of interest in the well-being of this population is that it is usually assumed that well-being and psychopathology are the extremes of a continuum, in the same way as this was previously assumed for positive and negative emotions. This is not the case. Mental health and mental illness are related but distinct dimensions (Westerhof & Keyes, Reference Westerhof and Keyes2010). More than a decade ago, the World Health Organization defined health as “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes their own abilities and can cope with the stressors of the day to day, work productively and make contributions to their community” (World Health Organization, 2004, p. 11); in other words, the absence of disease does not necessarily indicate the presence of health (Westerhof & Keyes, Reference Westerhof and Keyes2010).

Well-being is a key concept to understand positive mental health (see Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment, PERMA; Seligman, Reference Seligman2011). Well-being conceptualization has evolved over recent decades. The concept of subjective well-being included a cognitive aspect (i.e., life satisfaction) and an emotional aspect (Diener, Reference Diener1984). Ryff and Keyes (Reference Ryff and Keyes1995) considered psychological well-being to be a multifactorial concept that includes self-acceptance, life purpose, autonomy, positive relationships, environmental mastery and personal growth.

PTSD symptomatology and well-being are inversely correlated but the magnitude is not as great as might be expected (Díaz et al., Reference Díaz, Stavraki, Blanco and Bajo2018; Marín et al., Reference Marín, Hervás, Gómez, Crespo and Vázquez2019). The treatment and improvement of PTSD symptoms are associated with an increase in well-being. However, the magnitude of the association is, again, quite small (Berle et al., Reference Berle, Hilbrink, Russell-Williams, Kiely, Hardaker, Garwood, Gilchrist and Steel2018). In the aftermath of a terrorist attack, positive emotions may be present, along with suffering and PTSD symptoms (Fredrickson, Reference Fredrickson, Tugade, Waugh and Larkin2003; Vázquez & Hervás, Reference Vázquez and Hervás2010).

Several questions remain unanswered: How does the concept of well-being change after a terrorist attack? Do victims consider that they can achieve well-being? What are the factors that modulate it? Despite the increase in research related to the effects of attacks on the development of PTSD, there is no parallel increase in the study of well-being in this population.

Qualitative methodology allows an initial approach to relatively unknown study areas (Morgan & Krueger, Reference Morgan, Krueger, Morgan and Krueger1993). Further, it generates a completely different type of result compared with quantitative methodology. It is not only interesting to know what victims say about well-being, but also how they express it (Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson1998). Qualitative methodology has been used with interesting results when approaching post-traumatic growth and quality of life in trauma not related to terrorist attacks (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Renner and Danis2012; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Wohl and Verberg2007; Haun et al., Reference Haun, Duffy, Lind, Kisala and Luther2016; Palmer et al., Reference Palmer, Murphy and Spencer-Harper2017; Woodward & Joseph, Reference Woodward and Joseph2003). As regards qualitative research on the specific effects of terrorist attacks on mental health, several studies have been conducted on this issue; however, most of them worked with victims of September 11 and focused on psychopathological symptoms (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, North and Pollio2017; North et al., Reference North, Barney and Pollio2015, Reference North, Pfefferbaum, Hong, Gordon, Kim, Lind and Pollio2010, Reference North, Pollio, Pfefferbaum, Megivern, Vythilingam, Westerhaus, Martin and Hong2005).

Among the different qualitative approaches, focus groups were used in our study. A focus group is a way of collecting qualitative data using a small sample engaged in an informal discussion centered on a topic and guided by a moderator (Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson and Silverman2004). This not only provides information about the opinion of the participants but also about their natural language. Previous works on traumatic situations point out the importance of understanding these experiences in interaction, as a shared event (Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Blanco and Díaz2016).

This is the first study to use focus groups and qualitative analysis to study the well-being of victims of terrorist attacks, more specifically the attacks of March 11 in Madrid (also referred to as 11M). The scope of this work is entirely exploratory. The study starts with four main objectives: First, to obtain an initial qualitative approach to what the victims of 11M understand when talking about well-being. Second, to see if they currently enjoy well-being or if they believe they can enjoy it in the future. Third, factors that promote and interfere with victims’ well-being. Finally, to analyze whether there may be differences in all these aspects between direct victims and indirect victims.

Method

Participants

All the participants belonged to the “Association 11M Affected by Terrorism”. They were contacted through the association’s psychologists from among patients who were undergoing treatment or had previously been undergoing treatment.

Participants had to be aged 18–65 and be direct or indirect victims of the 11M attacks. Direct victims were those people who experienced the attacks first-hand, while indirect victims were relatives of people who died or were injured.

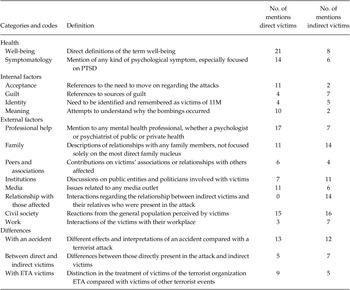

There were 16 participants who agreed to enter the study. Two discussion groups were held, one with direct victims (n = 6) and the other with indirect victims (n = 10). Most of the participants were under psychological treatment at that time or had completed it. Table 1 shows the demographic data of the participants.

Table 1. Sociodemographic Data

Note. NA = Not available.

Procedure

The groups were held on May 24, 2016, at the headquarters of the “11M Association Affected by Terrorism”, in Madrid, Spain. The direct victims’ session was held first. The focus groups lasted an hour and a half each. They were led by two researchers, who raised the issues and facilitated the dynamics. One more member of the work team oversaw the recording. A non-directive position was always adopted, only intervening when new information on a specific topic no longer appeared or when the discussion moved too far away from the research objectives. To begin, the study team was introduced, and the basic rules of interaction were explained. Subsequently, the researchers allowed each of the participants to present themselves freely.

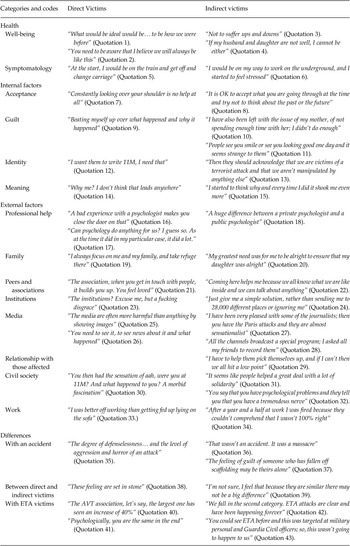

Certain questions were prepared to inquire into relevant aspects of research if they were not generated spontaneously by the groups. The topics to be addressed were divided into three large blocks, presented in Table 2: Definition of well-being, factors that facilitate well-being, factors that hinder well-being. Not necessarily all of them came up in the discussion and on occasion the groups introduced some related topics not previously contemplated. This structure was used in both groups.

Table 2. Key Themes and Subthemes Addressed by the Research Team

The sessions were recorded with the prior consent of the participants, in order to be able to transcribe them and analyze their content. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Complutense University of Madrid with code 2016/17–020. All participants signed an informed consent document before starting.

Data Analysis

The audio records were transcribed and transferred to the Atlas.ti version 7.5.7 text analysis program (2015). A classic content analysis of the transcripts was performed. This analysis works on the issues generated by the group, not those foreseen by the researchers. This type of analysis seeks to reduce the complexity of texts by categorizing fragments of them (Scandroglio & López, Reference Scandroglio and López2007).

The analysis process was developed by the first author. The process was carried out iteratively and cyclically. In a first reading, preliminary themes were noted by selecting fragments that exemplified them. In a second round, codes were generated based on the themes and examples, in addition to checking whether the fragments initially selected were maintained. The process was repeated on four occasions, each time trying to eliminate excess codes and outline the appropriate definition. The aim was to have clearly differentiated thematic codes sufficient to summarize the interviews. The approach to the analysis was exclusively exploratory. Given the scant literature on this subject in the population that concerns us, the work of Díaz et al. (Reference Díaz, Stavraki, Blanco and Bajo2018) allowed a first guide to some of the topics.

The analysis was done simultaneously with the transcripts of direct and indirect victims to avoid generating different code groups unnecessarily. The word code refers to the specific name given to the topic for analysis, but code and topic are used interchangeably here. Once the codes were considered final and all had associated examples, those that most clearly reflected them were selected for inclusion in drafting this paper.

Results

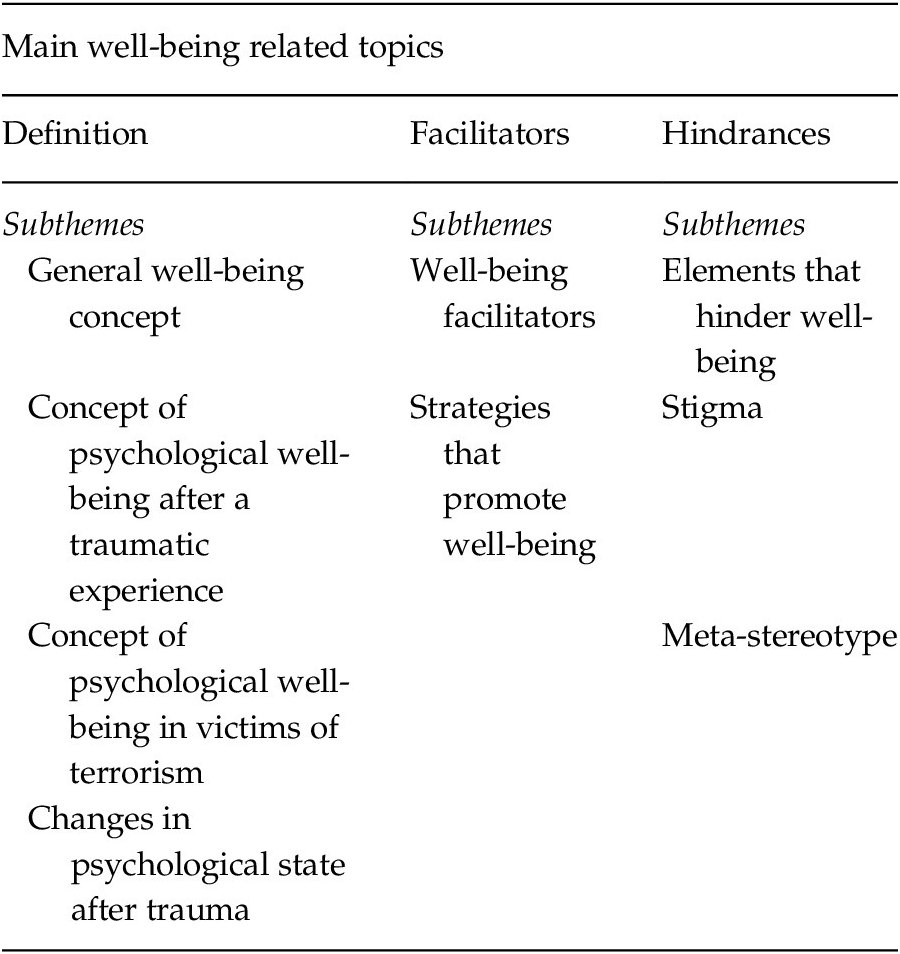

Seventeen topics were identified. Table 3 presents the codes assigned to each of the topics, as well as a brief definition and the number of engagements in each of the two groups of participants. Finally, some upper-level categories were generated by semantic resemblance to simplify the structuring and reading.

Table 3. Topics Discussed by the Focus Groups

Note. The table includes the codes generated after performing the thematic analysis. To characterize them, the following are included: The name of the code, the definition that justifies the inclusion or exclusion of certain citations, the number of citations labeled with that code in each of the groups of victims and a category later assigned by the researcher in order to group and simplify reading.

First, the construction of the various categories is justified. The first group, health, includes definitions of health as well as symptoms. As regards the factors, everything that affects the well-being of the groups, regardless of the direction they took. This is presented subdivided into internal factors (emotions and thoughts) and external factors (other people or organizations). Those opinions or comments regarding differences perceived with other victims of different traumatic events are included together in a fourth group.

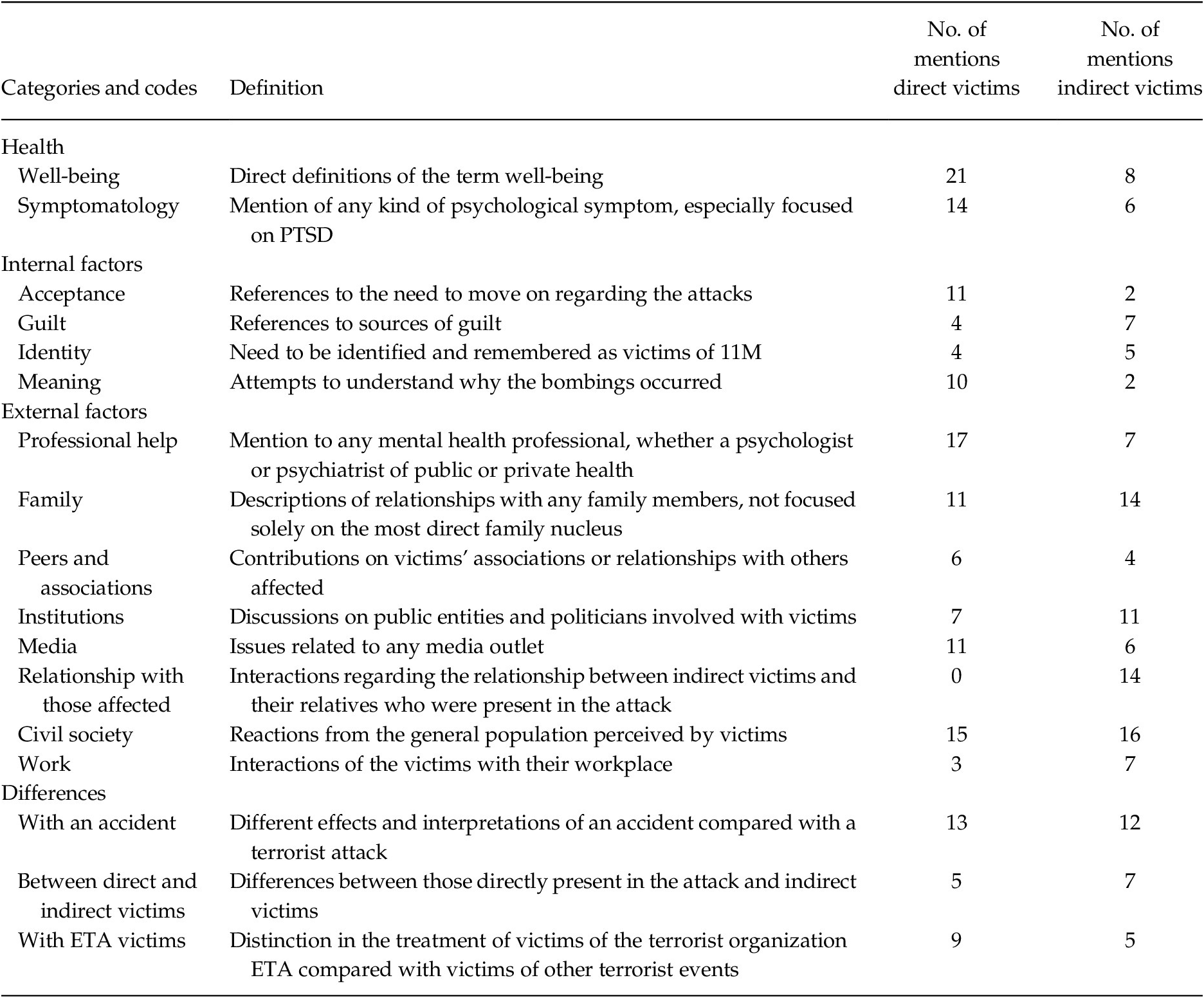

Representative examples of the different codes are shown in Table 4, to be subsequently explained. The citations are presented translated from Spanish but respecting how they were originally stated by the participants.

Table 4. Examples of Quotes from Each Code

Note. AVT = Asociación de Víctimas del Terrorismo; 11M = 11 de marzo del 2004; ETA = Euskadi Ta Askatasuna, Spanish terrorist group. Examples are numbered for ease of reading.

Health

Well-Being

Both direct and indirect victims spoke of well-being as excitement and emotional stability (Quotation 3). All victims found well-being difficult to achieve, even saying that the only way to obtain well-being would be to go back to the day before the attacks (Quotations 1 and 2). Only direct victims pointed to the association between physical and psychological well-being, also emphasizing the presence of physical symptoms as a key aspect. On the other hand, indirect victims’ well-being was heavily associated with that of their directly affected relatives (Quotation 4).

Symptomatology

Both groups commented on the presence of fear and avoidance behavior in situations reminiscent of the attacks (Quotations 5 and 6). Psychological symptoms were more discussed in the group of direct victims, especially those associated with PTSD. Indirect victims hardly referred to their own symptoms, focusing on those of their relatives.

Internal Factors

Acceptance

All victims pointed to the importance of moving past the damage caused by the attacks (Quotations 7 and 8). Direct victims tried to differentiate the idea of acceptance and resignation, acceptance implying an active approach. This is a relevant issue and with similar nuances in both groups but was more thoroughly discussed by direct victims.

Guilt

Both groups of victims felt stigmatized for feeling better or taking time for themselves (Quotation 11). Aside from that, the reasons behind guilt on direct and indirect victims were substantially different. Direct victims felt guilty for having survived the attacks (Quotation 9), while indirect victims felt guilty for having received financial aid or for not being able to understand how their family members felt (Quotation 10).

Identity

Both groups spoke about the need for recognition as victims of 11M (Quotation 12 and 13). They need to specify what they have suffered, as a kind of badge.

Meaning

Both groups spoke about trying to understand the reasons for the attack; the contradictory relationship between needing to know more information and the pain stemming from trying to do this was discussed (Quotations 9, 14 and 15).

External Factors

Professional Help

Very marked differences were observed at an intragroup but not an intergroup level. Some participants were tired with mental health professionals (Quotation 16) while others remarked that these professionals have been a key help (Quotation 17). They also provided some insight on what problems they have encountered or what needs have not been met when using these services (e.g., differences between private and public services, Quotation 18).

Family

This code includes all interactions between family members except those that occur between indirect and direct victims, which are included elsewhere. Direct victims pointed to their family as a very important source of support (Quotation 19); however, indirect victims reported having to bear a great weight, feeling the need to appear happy in front of the rest of the family (Quotation 20).

Peers and Associations

Direct and indirect victims said they felt very supported by other victims and their associations (Quotations 21 and 22).

Institutions

This code was widely discussed in both groups, with similar content and quite negative emotions associated with it (Quotations 23 and 24). They felt forgotten and used by the government. The help received was not perceived as fair or effective. Indirect victims also blamed the attacks on the political decisions taken in the previous years.

Media

There was a markedly negative tone associated with this topic. The repetition of images of the attacks were harmful to them and they felt used and manipulated (Quotations 25 and 27). However, this coexisted alongside a strong need to continue using the media to find out more about the attacks (Quotations 26 and 28).

Relationship with Those Affected

This is the only code that does not appear in both groups, only being present for indirect victims. This may be considered a split from the family theme; however, it differs greatly in its content and only includes the relationship between direct and indirect victims. Indirect victims spoke in detail about the emotional climate after 11M. Although most of the emotions reflected are negative, there are also some positive ones. Having a great difficulty understanding how direct victims felt was repeatedly shared, associated with frustration. The difficulties separating one´s own emotions from those of direct victims was a key point (Quotation 29).

Civil Society

In both groups, a great deal of importance was given to how society viewed those affected by 11M. There were more differences between participants than between groups. While some participants felt support from society (Quotation 31) others felt forgotten and isolated (Quotation 32). Both groups said that they felt that some people looked at it morbidly or judged the victims (Quotation 30).

Work

Victims felt poorly understood in their workplaces (Quotation 34), although some participants benefited from being able to keep going to work (Quotation 33).

Differences

Differences from an Accident

Both direct and indirect victims considered that terrorist’s attacks and accidents are very different phenomena, especially considering the degree of uncertainty, defenselessness and fear (Quotations 35 and 36). Even so, in both groups, some participants argued that the consequences after an accident or an attack are similar. Indirect victims argued that in an accident the person involved may have some degree of agency whereas in an attack that is not the case (Quotation 37).

Differences between Direct and Indirect Victims

Direct victims perceived that symptoms and the direct experience of the attack were haunting and separated the two groups (Quotation 38). Indirect victims didn´t see any differences between the groups (Quotation 39).

Differences with ETA Victims

Before explaining this section, it is necessary to point out some peculiarities of terrorism in Spain. Although 11M was a jihadist attack, Spain previously experienced many attacks carried out by the national terrorist group ETA (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna or Basque Country and Freedom). The existence of a terrorist group in Spain generates issues such as comparisons between victims (i.e., ETA vs. jihadism).

This is one of the topics that presented the most disagreement at an intragroup level, leading to heated discussions. However, there was fairly widespread agreement between the participants of both groups regarding feeling less recognized than the victims of ETA (Quotations 40 and 42). The discussion began between those who did not observe great differences (Quotation 41) and those who considered that ETA attacks were directed against specific groups, while 11M attacks affected anonymous civilians (Quotation 43).

Discussion

This study aimed to make an initial approach to the well-being of the victims of 11M. After carrying out the focus groups and conducting a thematic analysis of the content, we are somewhat closer to understanding how this specific population views the concept of well-being.

Victims understand that well-being is linked to balance, hope and inner peace. As might be expected, they associate their well-being with the absence of symptoms, both psychological and physical. This is similar to the findings of other previous works (Bromet et al., Reference Bromet, Hobbs, Clouston, Gonzalez, Kotov and Luft2016; Díaz et al., Reference Díaz, Stavraki, Blanco and Bajo2018). Indirect victims consider the health of their directly affected family members as a key point in defining their own health and well-being. Regardless of the presence of symptoms, well-being was not achieved by a significant part of the participants. Despite being a factor with multiple components, as mentioned above, it was automatically associated with the absence of suffering in both groups without going into other issues such as personal growth or coping skills, which do appear in other samples not exposed to traumatic events (McKinlay et al., Reference McKinlay, Fancourt and Burton2021; Slade et al., Reference Slade, Rennick-Egglestone, Blackie, Llewellyn-Beardsley, Franklin, Hui, Thornicroft, McGranahan, Pollock, Priebe, Ramsay, Roe and Deakin2019)

Another of our objectives was to discover the factors that interact with well-being. Regarding factors that facilitate well-being, both groups point out that victims’ associations are of great help, due to the feeling of understanding and unity. This has been reflected in previous works, although it is established that sharing this kind of emotion is a double-edged sword, initially leading to greater rumination and maintenance of negative emotions, but also associated with greater post-traumatic growth (Rimé et al., Reference Rimé, Páez, Basabe and Martínez2010). Acceptance is also a key factor. Both groups commented that being able to accept what happened and move on are crucial aspects of recovery. Studies focused on acceptance and commitment therapy in PTSD draw similar conclusions (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Arnkoff and Glass2011).

Speaking about those factors that hinder well-being, similarities also appear between the two groups. The presence of symptoms is one of the greatest difficulties when it comes to achieving well-being. The tendency to speak of symptoms when being asked about health has already been observed in other population groups suffering from PTSD (Haun et al., Reference Haun, Duffy, Lind, Kisala and Luther2016). This is reflected in both groups, but more markedly with direct victims. However, it could be argued that there is a certain degree of denial of their own discomfort on the part of indirect victims, as a care role is expected from them. Guilt also appears in both groups, although in a more pronounced way in indirect victims (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Droždek and Turkovic2006). According to the views of participants, the representation of the attacks in the media and the tendency to speculate about them has caused great harm. This phenomenon has already been studied, especially in relation to the dreams of the victims (Propper et al., Reference Propper, Stickgold, Keeley and Christman2007). However, it is simultaneously observed that there is a considerable need to use the media to obtain more information about the attacks. This is related to another aspect that has been considered counterproductive for well-being in this work -the search for meaning. Previous models suggest that finding meaning helps post-traumatic growth (Park, Reference Park2016). However, in our case it seems that participants are looking for meaning, but not finding it. A prolonged and unfruitful search for meaning may be associated with the discomfort that some of the participants experienced. Something similar is observed with the treatment received from political institutions, finding the aid they receive ineffective and considering that there is a differential treatment with respect to other groups of victims. Similarly, to the relationship established between the media and meaning, institutions and identity as a victim are associated. Although clear opinions cannot be established with the information obtained, it is necessary to delve into the role that identity plays in achieving well-being, as well as the relevance of victims’ organizations in developing such identity. Some previous works indicate that turning trauma into part of identity is associated with higher PTSD scores (Berntse & Rubin, Reference Berntsen and Rubin2007).

Regarding those factors that play an ambivalent role, participants raised issues about work, professional help and civil society. Work acted to some extent as a distraction and provided some normality after the attacks. However, in turn, the organizational structure showed very little understanding of the psychological symptoms, something reflected in other studies (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Dunn, Amlôt, Rubin and Greenberg2019; North et al., Reference North, Pfefferbaum, Hong, Gordon, Kim, Lind and Pollio2010). Professional help presented a similar phenomenon. For some victims it was essential, while others were very disappointed. They comment on feeling differences between private and public treatment, as well as between medical and psychology professionals. This issue deserves attention on its own, since it may have a special weight in terms of adapting the psychological treatment given to this population. It is also observed that stereotypes and stigma about mental health prevent some victims from seeking help (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Dunn, Amlôt, Rubin and Greenberg2019).

It is now necessary to observe the main differences between direct and indirect victims. The family is perhaps the biggest point of distinction. While it plays a very positive role in direct victims, as already noted, for indirect victims it is a source of support, but also of frustration (Stevens et al., Reference Stevens, Dunsmore, Agho, Taylor, Jones, van Ritten and Raphael2013). Indirect victims felt they had to appear strong when they were also affected. They speak of the difficulties in helping the direct victims. Indirect victims associated this situation with guilt and the denial of one’s own needs. The vision of civil society is another differentiating point. Society provides benefits and difficulties for both direct and indirect victims but shows a somewhat darker side in the eyes of the latter. Society is a considerable source of guilt, and they often felt judged, although this could also be taken as a sample of the self-stigma of the participants (Bonfils et al., Reference Bonfils, Lysaker, Yanos, Siegel, Leonhardt, James, Brustuen, Luedtke and Davis2018).

This study presents some limitations. First, the small sample prevents generalizations about the well-being of all victims of terrorism. By only targeting 11M victims and having only one focus group for each type there is a risk of bias. However, this study, as it was exploratory, did not seek to generalize so much as to discover new avenues of research.

Participants selection criteria could also be a source of bias, since all of them were undergoing treatment (or had already finished it). But ethical and clinical criteria guided the decision. Including people with symptoms could be harmful and could also hinder the proper development of the groups.

Another problem is that the codes and snippets were only selected by one person. Having used focus groups rather than in-depth interviews may have affected the issues that emerged. However, the use of individual interviews makes it impossible to access the interactions between members, an important objective of this work.

Due to the meta-stereotypes of the victims or the fear of being judged, they may have modified their way of talking about certain topics. However, since direct and indirect victims were grouped separately, this problem should be minimal.

Finally, the amount of time that has passed since the terrorist attacks may alter the results substantially, while allowing us to observe the long-term effects.

Beyond these limitations, the high specificity of the sample has generated its own themes that would not appear in other populations. For example, Spain is one of the few countries that have experienced terrorist attacks by an autochthonous group, which generates issues such as differences between victims, which are not expected in other victims. In addition, the specificity of well-being indicates that answers are clearly dependent on culture and nationality (Vazquez & Hervas, Reference Vazquez, Hervas, Knoop and Fave2012).

In brief, this study does not allow generalizations, given the size and specific characteristics of the sample, but it does act as a door to future work. Regarding possible future directions, there is a lot to research on the well-being of victims of terrorism. The role of the family, the treatment of the media and politicians and the type of help given by mental health professionals are issues that should be considered for new studies in the future. Of special relevance is the variability felt in mental health care. As the victims point out, a bad experience can lead to closing the door on these services, and this seems to be a relevant topic for future study. Future research might explore whether specific interventions for increasing well-being in victims of terrorism are feasible and useful. Another crucial point is the special needs of family members. Given that they do not present as many symptoms their need for psychological attention may be overlooked. Guilt appears nuclear, and communication difficulties may be one of the focuses of the treatment when attending to indirect victims.

This work has allowed an initial approach to well-being in victims of terrorist attacks using a qualitative strategy rarely attempted in this population group. It opens up more questions than it can definitively answer, thus fulfilling its role as an exploratory work. Many aspects have been suggested that might be associated with the lower levels of well-being typically found in this population group. Additionally, direct and indirect victims present a lot of similarities, but also specific needs and complaints that must be taken into account. Victims of terrorism struggle to achieve previous levels of well-being. However, in-depth research is needed to confirm or deny such hypotheses. Future studies could use mixed methodologies to study well-being in this group and even compare them with non-victim samples.