Introduction

The Supreme Court of the United States has evolved over time, both in the scope of its powers (Chafetz Reference Chafetz2017) and the extent to which the public regards it as an ideological institution (Davis and Hitt Reference Davis and Hitt2023; Gibson Reference Gibson2023). One constant over the years, however, has been allegations that political crisis surrounding and produced by the Court may have spillover electoral effects. In a separation of powers system (Chafetz Reference Chafetz2017), Congress is expected to check the other branches when they overreach or otherwise abuse their authority, channeling the anger of the electorate (Carrubba and Zorn Reference Carrubba and Zorn2010; Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011). As of 2023, the median justice of the U.S. Supreme Court is more conservative than it has been in nearly a century (Brown and Epstein Reference Brown and Epstein2023), culminating in the widely unpopular overruling of Roe v. Wade (410 U.S. 113, 1973) and historic lows in public approval (Pew Research Center 2022). It may seem reasonable, then, to expect that voters would channel their dissatisfaction with this countermajoritarian trajectory through electoral mechanisms (Bouie Reference Bouie2022). On the other hand, it seems that the Supreme Court of the United States may freely engage in sharply ideological decision making without serious fear of reprisal from the other branches (Owens Reference Owens2010), even as those very decisions damage its perceived legitimacy among partisans (Davis and Hitt Reference Davis and Hitt2023; Gibson Reference Gibson2023; Strother and Gadarian Reference Strother and Gadarian2022).

In this paper, we investigate why this status quo regarding reform persists. First, echoing Badas and Simas’ (Reference Badas and Simas2022) recent work, we analyze original nationally representative survey data that reveal that most citizens do not perceive the Supreme Court to be a top priority in their vote. If the elected branches are meant to punish an out-of-step Court (Carrubba and Zorn Reference Carrubba and Zorn2010; Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011), then an electoral connection would demand that voters actually care about the Court as a political issue (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974). Although we find that this is not the case, important individual differences in the perceived importance of the Court do exist (Hitt, Saunders, and Scott Reference Hitt, Saunders and Scott2019). We show that diffuse support is critical to the extent to which the Court is electorally salient – persons who exhibit higher levels of diffuse support are more likely to convey that the Court is important to their electoral decisions.

Second, that finding has some bearing on receptivity to messaging about reform. Using a simple survey experiment, we show that while Republican subjects do not perceive a hypothetical congressional candidate who opposes reform any more favorably than a candidate who takes no position at all on the Court, Democrats view a pro-reform candidate as modestly stronger. Yet there is nothing in our data to suggest that liberal political entrepreneurs should pursue Court-curbing strategies. Not only is the Court’s electoral relevance among Democrats low, but their expressions of diffuse support for the Court have soured (Davis and Hitt Reference Davis and Hitt2023). In theory, when legitimacy maps onto partisan sorting in this way, institutional cross-pressures ought to cease to act as a bulwark against calls to reform the judiciary (c.f. Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2015). However, individuals who do not perceive the Court as legitimate (overwhelmingly Democrats) also do not perceive the Court as an important electoral issue. As such, a dynamic of public backlash against the Court’s decisions as mediated through Congress (Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011; Mark and Zilis Reference Mark and Zilis2018) may no longer hold given new partisan sorting of diffuse support. We speculate that the result of these developments means that the vital electoral connection that would otherwise motivate members of Congress to check an out-of-step Court now functions poorly, weakening Congress’ oversight role and the overall balance of America’s separation-of-powers system of governance (Mark and Zilis Reference Mark and Zilis2019; Redish Reference Redish2017).

The Court and claims of public backlash

Claims that the Court’s institutional outputs will result in (partisan) backlash are not infrequent. Consider, for example, two episodes that provoked claims that the Court’s rulings might result in downstream repercussions through electoral (and, therefore congressional) channels (Carrubba and Zorn Reference Carrubba and Zorn2010; Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011; Vanberg Reference Vanberg2005). The 2000 presidential election pitted incumbent Vice President Democrat Al Gore against Republican George W. Bush. Despite over 101 million votes being cast, the election wound up hinging on several thousand duly-cast votes across the state of Florida. The narrow margin of victory by Bush was minuscule and permitted a hand recount, but the Supreme Court’s conservative majority ruled that recounting the votes was impermissible on the grounds that Florida’s recount rules were idiosyncratic across jurisdictions.Footnote 1 While the underlying legal rationale(s) for this judgment arguably lacked logical consistency and cohesion (Abramowicz and Stearns Reference Abramowicz and Stearns2001; Hasen Reference Hasen2004; Hitt Reference Hitt2019), the decision awarded the election to Bush, and Gore graciously conceded – but not before many speculated about the significant damage the decision might wreak in coming elections (Hasen Reference Hasen2004).

Similarly, and more recently, in June of 2022, The Supreme Court of the United States announced its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (No. 19-1392, 597 U.S. ____ (2022)), which overturned Roe v. Wade. By shifting the jurisdiction of reproductive policy exclusively to the states, the opinion allowed elected officials in several states to quickly mobilize to rescind a woman’s access to an abortion. The elimination of this liberty, coupled with several other controversial decisions during the same session, ranging from permitting public tax dollars to be spent on private, religious education to striking down regulations guiding concealed carry laws, sparked a renewed round of calls to fundamentally reshape the American judiciary (e.g., Representatives Ro Khanna (D-CA) and Don Beyer (D-VA) and the introduction of “The Supreme Court Term Limits and Regular Appointments Act”). Again, there were claims that the 2022 midterm elections might serve as a referendum on the Court by left-leaning voters (Cillizza Reference Cillizza2022) who exhibited a new souring in the legitimacy of the Court that was distinct from the fallout from the Bush v. Gore (531 U.S. 98, 2000) decision (Davis and Hitt Reference Davis and Hitt2023; Gibson Reference Gibson2023).Footnote 2

Curiously, the thread binding these different high-profile events together is the common muted institutional consequences that they have thus far produced. Despite such serious interventions into the lives of citizens, ranging from deciding a presidential election, to removing hard-won and popular civil liberties, the Court continues to conduct its business without generating any constraint on its powers from Congress (Owens Reference Owens2010). Although the Court’s recent decisions appear to be broadly unpopular with the American public and the institution itself enjoys less popular approval (specific support) today than in previous eras (Pew Research Center, September 1, 2022), perhaps a historical reservoir of perceived legitimacy (Easton Reference Easton1965) allows the Court as an institution to successfully resist calls to fundamentally transform or reform it (Clark Reference Clark2011).Footnote 3 But, given allegations that the Court has become a minoritarian political backstop, how does the public respond to politicking about reforming it?

Answering this question requires first understanding whether attitudes about the Court spill into electoral preferences among the American mass public. Is the Supreme Court an issue of electoral relevance? Are calls to reform the Court politically palatable? Can political entrepreneurs use Court reform as a mobilizing issue with voters?

Electoral accountability and the Court

Clark’s work (2009) suggests that an out-of-step Court angers the public, and that, in turn, this anger is communicated to the justices via the proposal of Court-curbing legislation (see also Carrubba and Zorn Reference Carrubba and Zorn2010). The trouble with the claim that the Court may produce electoral backlash, however, inevitably runs headlong into the institution’s inbuilt protections – by design, the Supreme Court sits beyond the immediate reach of voters. Yet, despite this feature of the United States’ system of checks and balances, voters do play an indirect role in shaping the federal judiciary (Dahl Reference Dahl1957). Presidents nominate justices, and the Senate confirms them, but neither performs their role without first being elected by the people. Voters are first-movers, choosing representatives who, in turn, fill positions in this peculiar institutional body.Footnote 4 Elections, then, have significant judicial consequences. The public’s electoral connection to the legislature allows for indirect communication between voters and the justices via Congressional action (Clark Reference Clark2009; Mark and Zilis Reference Mark and Zilis2019).

Of course, this arrangement supposes that voters not only pay attention to vacancies (real or potential), but that they understand the implications involved in the composition of the Court’s ideological makeup. Although political knowledge among the public is reliably modest, casting some doubt upon the notion that the public pays attention to the minutiae of Supreme Court’s behavior (Hitt, Saunders, and Scott Reference Hitt, Saunders and Scott2019), the public nevertheless expresses interest in Supreme Court nominations come election time.

Consider, for instance, popular polling from Pew in 2016 that suggested that “[a]bout three-quarters of conservative Republicans and Republican leaners (77%) say the issue of Supreme Court appointments will be very important to their vote … Similarly, among Democrats and Democratic leaners, more liberals (69%) … see court appointments as very important to their 2016 vote.”Footnote 5 Badas and Simas (Reference Badas and Simas2022), likewise, find that the public responds to candidates differently on the basis of the promises they make regarding Supreme Court nominees. Copartisan candidates who offer to confirm in-group justices can affect how partisans vote.

If nomination preferences involve decisions about inputs, then, presumably, the outputs of the Court also ought to matter to voters. How the Court behaves and the decisions it produces are a direct reflection not just of statutory interpretation but offer a window into the nation’s values. Yet, perhaps ironically – at least from an Eastonian point of view – the Court’s outputs are historically more or less decoupled from public evaluations of the institution.Footnote 6 A lengthy literature argues that the public gives wide latitude to the Supreme Court (Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2014). Even when it acts in ways contrary to democratic principles, the Court’s reputation as a legal entity detached from explicit partisan politics has traditionally sustained its popularity – although individual decisions may be more or less popular, the public accepts its place in American politics as binding and legitimate.

However, citizens do not naively believe in a mechanical, automatic version of judicial decision making, per se (Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira2011). Rather, it is the impression that rulings arise out of insincere or partisan considerations that is most damaging to the Court’s reputation (Baird and Gangl Reference Baird and Gangl2006). In this way, the Court’s significant rightward turn (Brown and Epstein Reference Brown and Epstein2023; Epstein and Posner Reference Epstein and Posner2022), alongside the damaging confirmations of the Trump era (Carrington and French Reference Carrington and French2021), has altered this stable perception of legitimacy (Gibson Reference Gibson2023), especially among Democratic partisans (Davis and Hitt Reference Davis and Hitt2023).

One reaction to this shift away from a post-New Deal consensus about the legitimacy of the administrative state and settled nature of civil liberty case law involves liberal and progressive politicians and commentators raising the possibility of limiting the Court’s authority to rule on such matters. Interest in court curbing cuts across traditional political cleavages: Clark (Reference Clark2011) and Bartels and Johnston (Reference Bartels and Johnston2020) reveal that conservatives and liberals have alternated in their demand for reforming the nation’s highest court. Regardless of the normative merits of such reforms, any alterations to the Court’s basic structure would naturally have to be initiated via political processes. While the partisan gap in Court approval has never been larger (Pew Research Center, September 1, 2022), it is unclear how preferences over Supreme Court reform might shape public impressions of partisan candidates for federal office during this period.

It is possible that the renewed salience of the Court in American politics means that Democrats (Republicans) more keenly support candidates who express support (opposition) for reforming the Court. High profile behaviors undertaken by the Court, when highlighted in the media, influence perceptions of the institution (Caldeira Reference Caldeira1987; Hitt and Searles Reference Hitt and Searles2018). That dovetails with more recent evidence that citizens expect members of Congress to behave in ways that are supportive of their party’s stereotypical goals (Sheagley et al. Reference Sheagley, Dancey and Henderson2022) and penalize copartisan candidates who violate such expectations (Orr and Huber Reference Orr and Huber2020).

However, even with renewed attention to the Court following Dobbs – the most nakedly ideological issue before the Court in recent memory – perhaps candidate evaluation and support are driven by other considerations like policy itself or basic social and partisan attachments rather than institutional support. Understanding how important the Court is to voters relative to other issues is key to unpacking this relationship: For example, citizens may give candidates more latitude to take counterstereotypical positions if the Court is of lower importance (e.g., Arceneaux Reference Arceneaux2008). If the Court matters to voters, however, then perhaps a candidate will not only have the motivation to curb it (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974) but can also improve their standing by highlighting their position on Supreme Court reform, creating certainty in citizens’ minds on an important issue (Peterson Reference Peterson2004).

In light of the power absorbed by the Court during an era of significant legislative gridlock and polarization (Binder Reference Binder2015; Chafetz Reference Chafetz2017), discerning between these possibilities enables scholars to understand the salience of the Court’s role in American politics after both the Dobbs decision and other, high-profile and controversial events involving the Court in recent years (e.g., Merrick Garland’s thwarted candidacy to the Court or allegations of sexual abuse against Brett Kavanaugh raised during his confirmation). The Supreme Court’s legitimacy is often staked to public support for the status quo regarding its composition and scope of powers (Badas Reference Badas2019). In the case that evaluations of electoral candidates who profess support for Court reform are positive, this result would imply that Court’s perceived legitimacy may be imperiled by recent events, its own actions, and identity-based impulses (Strother and Gadarian Reference Strother and Gadarian2022).

We investigate these themes in two studies. First, given the minimal attitudinal impact of Bush v. Gore (Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003; cf. Yates and Whitford Reference Yates and Whitford2002), we first explore the extent to which Americans consider Supreme Court reform as a meaningful public policy issue at all (Study 1). Second, while voters might purport to care about the Court in the abstract, candidates must strategically choose which issues to highlight in campaigns (Riker Reference Riker1986) and which policies to pursue once elected to office (Volden and Wiseman Reference Volden and Wiseman2014).Footnote 7 Here, we also experimentally test the extent to which partisans are receptive to in-party candidates running for or against reforming the Court (Study 2).

Of course, citizens vary in the relative weight they ascribe to various policy domains. Given that knowledge of the Court’s decisions in the first place is highly conditional on political sophistication (Hitt, Saunders, and Scott Reference Hitt, Saunders and Scott2019), we expect to find considerable individual differences in the relative importance of Supreme Court reform as a policy issue. One dimension along which Americans ought to vary in their valuations of Court reform as a policy domain is the relative amount of diffuse support they extend the institution. Dahl (Reference Dahl1957) argued that the Supreme Court’s membership is a downstream consequence of the electoral process via presidential nominations and Senate confirmations. Therefore, the Court’s decisions, on average, should not be too far out of step with the public mood for too long. This mechanism is vital for its legitimacy, as voters lack the ability to select the justices directly, given the legitimacy-conferring nature of electoral accountability (Riker Reference Riker1982). If the Court either lacks importance as an issue and/or if candidates cannot improve their electability via appeals to reform it (perhaps because prospective voters have ceased trusting the institution in the first place), then the elected branches may lack sufficient incentives to constrain an out-of-step, unelected, judiciary (Owens Reference Owens2010).

Study 1: modeling the electoral importance of the Supreme Court

Although past research has studied the relative importance of Supreme Court nominations (Badas and Simas Reference Badas and Simas2022), how the Court is ranked against other competing issues is unclear.Footnote 8 In other words, when voters are forced to rank-order issues by their perceived relevance to their decision making, how does the Court stack up against other salient issues of the day? Our general expectation here is that the Court would rank comparatively lower in importance to the guns and butter issues that dominate the most important topics in American political discourse. However, because this survey appeared during a moment of political upheaval surrounding the Court’s recent decisions, it is possible that prospective voters will be sensitive to the Court’s relevance and rate it comparatively more important than, say, taxes or foreign policy.

Sample

As part of a yearlong, multiwave survey project called the Supreme Court and Democracy (SCD) Panel Study, YouGov was contracted to collect data from panelists during the week before the 2022 November midterm election. The final sample includes the 1,384 participants who responded to the recontact email and took the full survey questionnaire. The wave 4 sample was representative of the wider mass public, displaying balance across race, gender, education, and ideology (see the appendix for full demographic details).Footnote 9

Measures

We asked subjects to rank seven issues on which they might base their vote, ranging from most (1) to least important (7). These issues involved a variety of items commonly listed in Gallup’s “most important problem” polling and included healthcare, taxes, education, abortion, the environment, foreign policy, and the Supreme Court.Footnote 10 These issues are all abstract in the sense that they are categories rather than policy prescriptions. We did not ask about policy solutions but, instead, the abstract or parent issue domains, a choice we made to try and create some parity with the level of abstraction represented in the “Supreme Court” option. It is true that the Court may absorb these issues in its rulings, but to ask about specific outcomes would defeat the purpose of a heads-up competition against abstract evaluative domains.

Our outcome of interest involves the “relative” importance of a given issue compared to all other issues.Footnote 11 To construct this measure, we averaged across all numeric ranks an issue received; an issue’s weighted importance allows us to assess which issues were most salient to prospective voters and, by extension, compare how Supreme Court reform stacks up against other competing issues.Footnote 12

In addition to a standard battery of demographic features including race, gender, age, political affiliation, and the like, we also posed several other questions to respondents regarding their views of the Supreme Court. Perceived court ideology ranges from “liberal” (low values) to “conservative” (high values). Judicial cynicism is latent variable constructed from a factor analysis of several statements that ask whether respondents reject mechanical, legalistic jurisprudence, and instead ascribe attitudinal motivations to justices and the Court (Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira2011). Diffuse support is latent variable constructed from a factor analysis of several statements that gauge sympathy for protecting the Court’s legitimacy and power (Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003). Finally, Court approval ranges from “disapprove” (low values) to “approve” (high values). Details involving measurement of these three indices and their constituent variables can be found in Appendix A.

Results

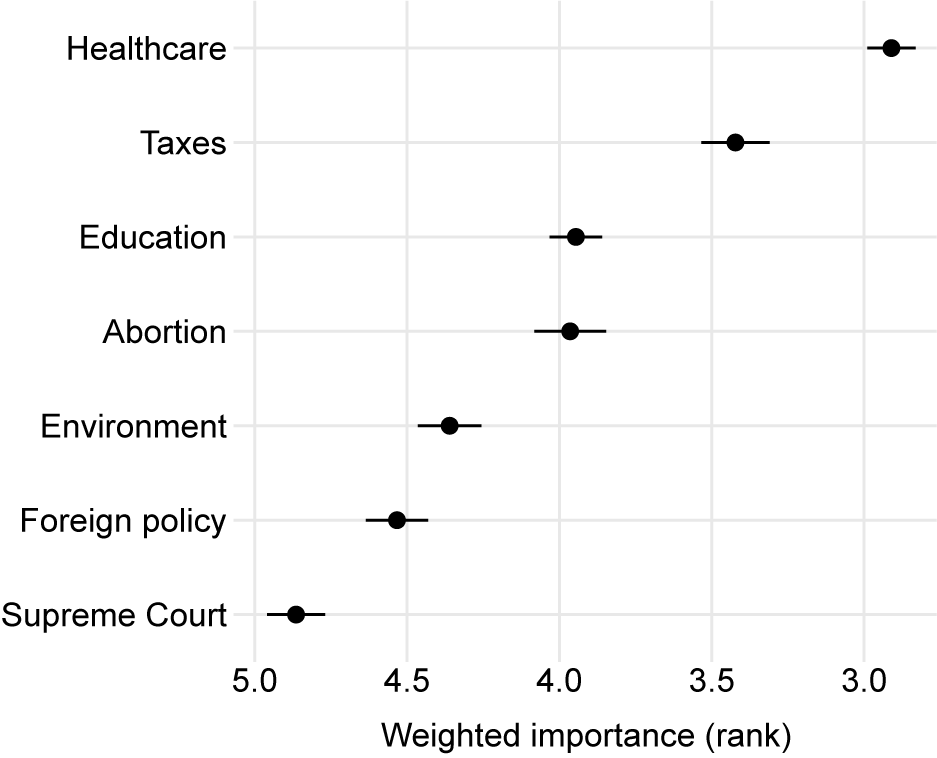

Figure 1 presents the cumulative importance of each of the seven “issues’ that we provided to respondents in the pretreatment survey. Here, lower (higher) values correspond to higher (lower) rankings of importance. Among the seven issues, healthcare receives the highest absolute rating of cumulative importance while the Supreme Court comes in dead last – almost two full ranks below healthcare. One reaction to this finding may be that concern over the Court’s role in issues involving healthcare or abortion spill more directly into those categories offered to respondents. It is true that prior to fielding this wave of the panel survey, the Dobbs decision was released to uproarious public reaction. However, in some sense, this is a strong test of whether specific anger at the Court is enough to shift it into primary electoral fodder. That is, if (dis)pleasure over the Court’s ruling was profound, then we should observe respondents assigning it a higher rank. That does not happen here. Even during a period where the Court ought to have been salient to voters, political issues remain more important than the institutions that constrain them. That disconnect has important implications not just for the political status quo but for the way in which voters weigh electoral appeals to reform the Court (Study 2).

Figure 1. Subject issue priorities for vote choice.

Notes: Subjects were asked to rank the issues above in terms of their importance to their vote choice. Point estimates reflect the cumulative importance of each issue; values were rescaled to range from one to seven. Lower (higher) values convey that those subjects viewed the respective issue to be more (less) important. We break these ratings down by partisanship in the appendix and find some differences: Republicans rate taxes as an extremely important concern, while Democrats rate abortion as a pressing matter; while the Supreme Court is dead last among Republicans, its ranking is roughly the second from the bottom (approximately tied with taxes and education).

In turn, what explains these rankings? Do demographic attributes or views about the Supreme Court affect higher or lower rankings of it? While partisanship might seem relevant, so, too, might attitudes involving how people regard the Court. A prevailing insight from almost 50 years of research on the Supreme Court, for example, suggests that it retains its legitimacy, in part, because voters buy the logic that Court actors are engaged in legal (or at least principled) and not partisan decision making (Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira2011; Baird and Gangl Reference Baird and Gangl2006). To what extent, then, do attitudes like judicial cynicism or diffuse support affect the Court’s ranking as electorally relevant?

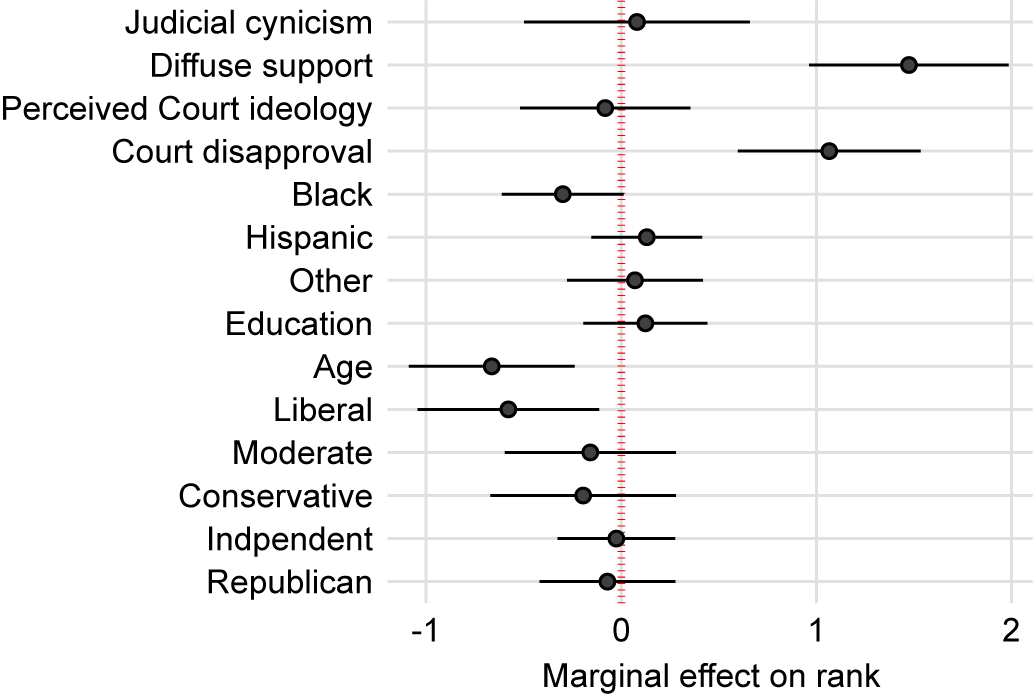

To answer this question, we regress the Court’s cumulative rank on a set of covariates that are often linked more generally to support for the Supreme Court. Figure 2 explores the correlates of Supreme Court rankings using a simple Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) model that incorporates both attitudes toward the Court and demographic attributes. Here, all coefficients have been normalized to range from 0 to 1 to ease comparisons about the magnitude of the relationships between variables; coefficient estimates that cross the dotted vertical line at the zero threshold are not statistically significant.

Figure 2. The correlates of ranking the Supreme Court in the voting calculus.

Notes: Figure displays coefficient estimates from model of Court ranking. Corresponding point estimates convey the marginal effect of moving from minimum (0) to maximum value (1) on given variable entry along y-axis, bracketed by 95% confidence intervals. For race, “white” is excluded category; “don’t know” is excluded category for ideological identification. “Democratic” identification is the excluded category for partisanship.

The results primarily convey two pieces of information. First, very few demographic characteristics correlate with how prospective voters think about the importance of the Supreme Court when evaluating candidates. There is some evidence that older and Black respondents are less likely to rank the Court as important. Personal politics also plays a minimal role in these rankings; while liberal respondents are a bit less likely to rank the Court as a pressing issue compared to people who did not choose an ideological label (the baseline category), partisanship has no effect on these ratings (the baseline category is “Democratic” partisanship).Footnote 13 In fact, the lone criterion that seems to move rankings in a substantively modest fashion appears to be both diffuse support and approval of the Court. Respondents who view the Court as a legitimate institution in American politics are much more likely to rank it highly than those who report weaker legitimacy, as are persons who are dissatisfied with its outputs.

Why? Perhaps individuals who hold the Court in high regard are more sensitive to protecting it during a time of upheaval regarding the Court’s role in American politics, while those with negative views of the Court are more likely to view it as a remote institution that is difficult to hold accountable. Nevertheless, it remains unclear how people may electorally respond to the Court when it is made salient by a political candidate. While this observational analysis is instructive, we turn next to a simple survey experiment designed to tease out the conditions under which priming the Court makes it relevant to prospective voters.

Study 2: Testing the electoral appeal of reforming the Court

While Study 1 illustrated that the Supreme Court ranks behind most other topics in the minds of American voters, this doesn’t mean that the Supreme Court is electorally unimportant, per se. Perhaps when an idea like Court reform is made explicit through an endorsement from a political candidate, prospective voters will become less ambivalent about the Court as an important electoral issue. Could a political entrepreneur strategically raise the salience of Court reform and thereby improve their electoral viability?

To answer this question, we designed a survey experiment that tests the relationship between candidate support and proposals for reforming the Supreme Court. Normatively, Court curbing functions as an intervention designed to impose accountability on an otherwise remote branch. In particular, proposals for term limits, which set the duration of how long justices may serve, have been debated since the founding (Giles, Blackstone, and Vinning Reference Giles, Blackstone and Vining2008). In theory, these limits brake the ideological drift between a justice’s ideological moorings and those of their appointing president that occurs as time transpires (Sharma and Glennon Reference Sharma and Glennon2013), while decreasing slippage between views of law and public policy that occurs between the mass public and the judiciary. In addition, they can further alter the authority of the Court more generally by making it more responsive to political demands (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2020). For our purposes, this issue cuts straight to the heart of the idea that voters who have soured on the Court might be willing to impose restraints upon it.

Views about curbing the Court via term limits, however, have not always mapped straightforwardly onto partisan cleavages (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2020). Further, both partisan identity and views about the Court appear to jointly shape public opinion on the matter (Black, Owens, and Wohlfarth Reference Black, Owens and Wohlfarth2023). As past research has demonstrated more generally (Staton and Vanberg Reference Staton and Vanberg2008; Clark Reference Clark2011; Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2023), the way in which courts, elected institutions, and the public interact often depends on how people make attributions of responsibility. Given the historic conservativism of today’s Court (Brown and Epstein Reference Brown and Epstein2023), it seems plausible that subjects will recognize that curbing the Court is now a more stereotypically liberal policy position. If so, then the partisan appeal of such position taking may be apparent to voters. As such, our basic expectations here are straightforward:Footnote 14

-

(1) Candidates who (do not) support Supreme Court reform will be evaluated as more liberal (conservative) (H1).

-

(2) Candidates taking party-stereotypical positions should be rated more strongly than candidates who take positions at odds with their group (H2).

Sample and design

All subjects who completed the questionnaire from Study 1 were block randomized by partisanship into one of three conditions in which they read a short, fictitious biographical sketch of a legislative candidate running for office during the upcoming midterm election. Subjects who professed a partisan preference were assigned to read about an in-party candidate, while “pure” Independent identifiers were randomly assigned to a Democratic or Republican candidate. Subjects in the control group were assigned to read the base vignette without any information about Supreme Court reform; subjects in the other two conditions read the same vignette with the addition of either a statement in support of or opposition to Supreme Court reform (see below, experimental text in italics).

{Democrat, Republican} Sam Smith is a veteran running for a legislative seat in the House of Representatives during the 2022-midterm elections. Sam is a small business owner who supports various charitable causes with his wife of 20 years, Vicky Smith. He wants to protect prescription drug benefits for the elderly and believes that the economy would be stronger if Americans produced and bought more of this country’s own goods. He is a strong supporter of improving early childhood educational opportunities. {(1: Control) No further text, proceed to post-treatment questions; (2: Support for SC reform) Sam also supports Supreme Court reform and has indicated he is open to term limits for sitting justices.; (3: Opposition to SC reform) Sam also opposes Supreme Court reform and has indicated he is against term limits for sitting justices.}

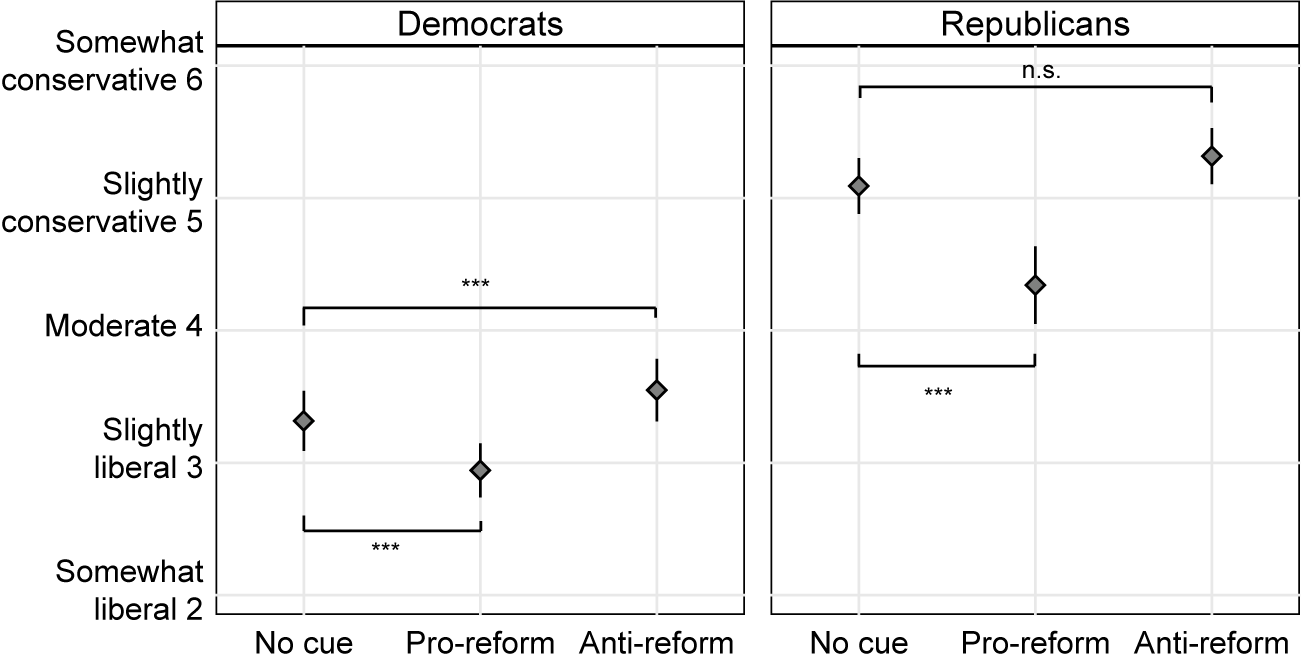

The biographical sketch was designed to be ideologically vague. Because we are only interested in the (marginal) effect of the reform endorsement on candidate strength, we needed to “hold constant” the candidate biographies, which means producing candidate descriptions that could be plausibly viewed as liberal and conservative (simultaneously). Despite a bevy of issue positions that are at best ideologically mixed, both Democrats and Republicans viewed the exact same depiction of an in-party candidate as ideologically commensurate to their partisan team in the “no reform cue” condition in Figure 3 (i.e., the control group). Nonpartisans, in turn, placed the candidate at nearly dead center in the liberal-conservative space. This approach was chosen to maximize the theoretical weight that prospective voters could attach to the subsequent information regarding the candidate’s views about reforming the Supreme Court.Footnote 15

Figure 3. Perceived candidate ideology.

Notes: Partisan subjects were block randomized to read about an in-group candidate running for legislative office during the 2022 midterm elections who communicated (1) nothing about the Supreme Court, (2) support for, or (3) opposition to reform (i.e., term limits). Subjects who identified as “pure” Independents were block randomized to read about a Republican or Democratic candidate in those same positions (for presentational purposes, these participants are excluded from the analysis in the figure). Point estimates convey the mean rating of the candidate’s ideology on liberal-conservative scale and are bracketed by 95% confidence intervals.

Measures

In the posttreatment questionnaire, we collected views about the candidates running for office. First, we asked subjects to evaluate whether the fictitious candidate was liberal or conservative. This measure of perceived candidate ideology ranged from 1 “very liberal” to 7 “very conservative.” We then followed with a measure of perceived candidate strength, where subjects were asked to communicate whether they believed the candidate was a strong or weak Republican or Democratic candidate. That variable ranged from 1 “not at all strong” to 4 “very strong.”Footnote 16

Results

Figure 3 illustrates perceived candidate ideology among subjects in the three conditions, broken out by partisanship. Because partisan subjects received an in-party label when reading about the fictitious candidate, we break apart these evaluations to assess how providing information about Supreme Court reform affects whether subjects view the candidates as liberal or conservative. The no cue condition illustrates that our vignettes “worked” insofar as the treatments were sufficiently bland that partisans could read their own preferences into them. The treatments made no mention of conventional partisan issues; instead, they balanced nonsalient “left” (prescription drug benefits), “right” (buying domestic products), and “bipartisan” issues (“the importance of early childhood education”). With only a partisan cue provided to them, Democratic and Republican subjects both viewed their co-partisan candidate as being slightly liberal (b = 3.31, Standard Error (s.e.) = 0.12) and conservative (b = 5.09, s.e. = 0.11), respectively, even though the candidates espoused verbatim issue positions across conditions.

For our purposes, then, the question is: What happens to candidate evaluations when additional (in)congruent information about the candidate’s views of the Supreme Court is incorporated? In the pro-SC reform condition, Republican respondents view the candidate as less conservative than the control condition (b = –0.67, s.e. = 0.16), while Democratic respondents view their candidate as modestly more liberal in the pro-SC reform vs. control conditions (b = –0.37, s.e. = 0.13). In contrast, while Democratic respondents perceive that their candidate is less liberal in the anti-SC reform condition compared to those in the control group (b = 0.46, s.e. = 0.13), Republican subjects across the anti-SC and control conditions do not differ in their ideological placements of the candidates (b = 0.28, s.e. = 0.16). On balance, then, group-congruent positions on Supreme Court reform taken by the hypothetical candidate moved evaluations of ideology in ways that correspond to stereotypical and pre-registered expectations (H1).Footnote 17

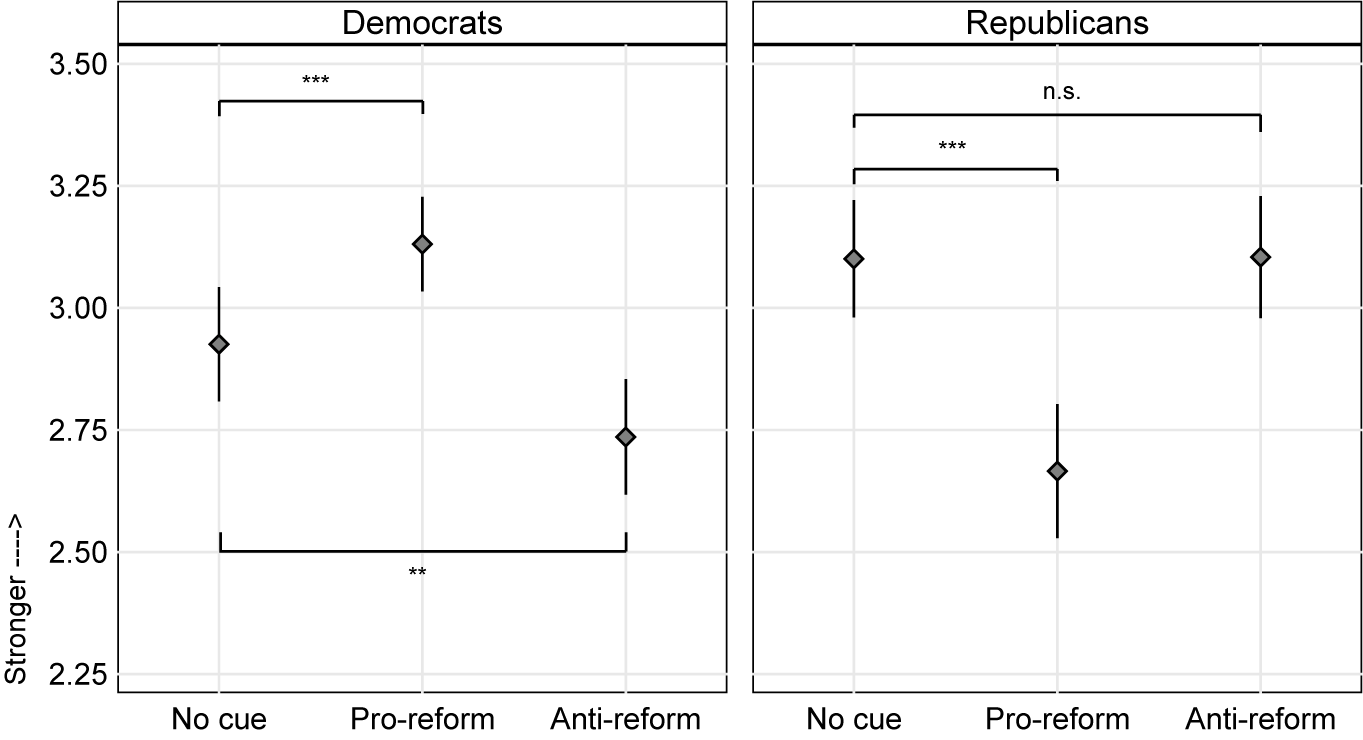

Given that the reform cue shifted perceptions of candidate ideology, do such cues, in turn, translate into views about the attractiveness of the candidates? That is, are candidates who take (in)congruent positions on the Court viewed differently? Yes, as Figure 4 illustrates. A Democratic candidate who takes a proreform position receives a modest boost in perceived strength over the candidate in the no-cue condition (b = 0.20, s.e. = 0.08), while a Democratic candidate who opposes such reforms is viewed as weaker (b = –0.19, s.e. = 0.08). In contrast, a Republican candidate opposed to Supreme Court reform receives no boost in strength (b = 0.003, s.e. = 0.09); however, the Republican candidate who took a party-incongruent position on reform was viewed as modestly weaker compared to the Republican candidate in the no cue condition (b = –0.43, s.e. = 0.09). In three of four cases, we find evidence in support of the prospect that candidate position-taking on Supreme Court reform matters for copartisans’ ratings of candidate quality.

Figure 4. Perceived candidate strength.

Notes: Point estimates convey mean perceived strength rating of a subject’s in-party candidate ranging from 1 “not at all strong” to 4 “very strong” and are bracketed by 95% confidence intervals. Subjects who identified as “pure” independents were randomly assigned to party candidates and are not depicted here.

The curious role of diffuse support

Our results to this point convey that (1) stereotypically congruent reform positions increase candidate appeal slightly for Democrats but not Republicans, and (2) stereotypically incongruent reform positions negatively affect candidate appeal for all partisans. But recalling the results presented in Study 1, diffuse support played an enormous role in how people connect the Court to electoral importance. Is it possible that this set of attitudes – which have historically been viewed as an important bulwark against support for reform (Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2015) – play a role in shaping views about candidates who (do not) support reforming the Court? Past research illustrates that both attitudinal beliefs (Peterson Reference Peterson2004) and partisan cues (Arceneaux Reference Arceneaux2008) impact electoral preferences; what happens when they interact in this scenario?

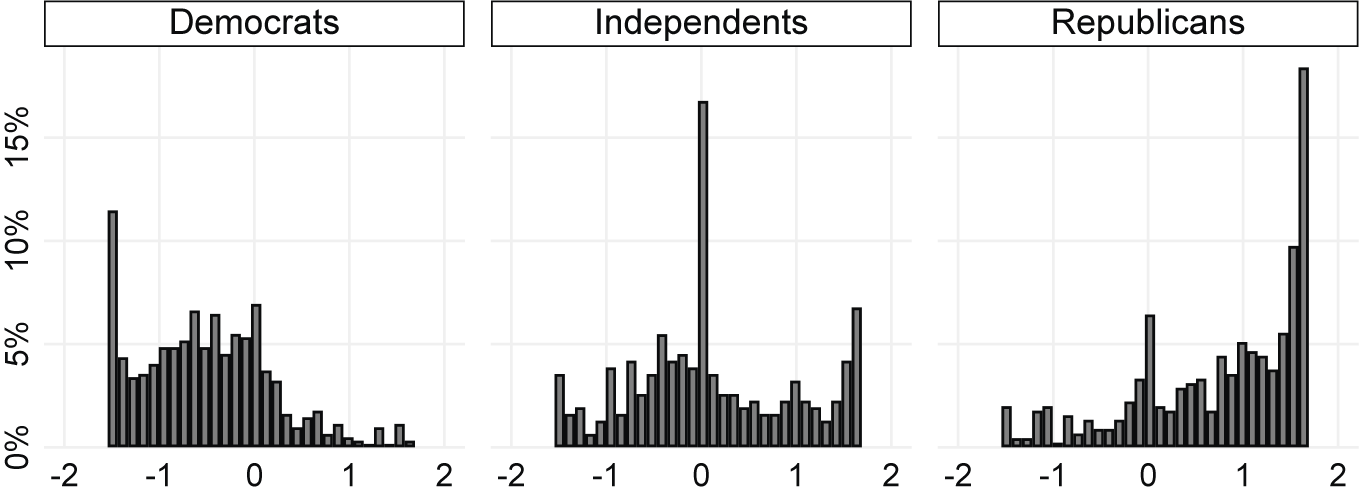

Historically, diffuse support has been equitably distributed among the public regardless of respondents’ partisan moorings (Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Nelson and Tucker Reference Nelson and Tucker2021). Partisans might disagree with the Supreme Court’s individual rulings, but with few consequences to institutional legitimacy (Badas Reference Badas2019). Yet, as more recent research indicates, there has been a curious sorting out of diffuse support (Davis and Hitt Reference Davis and Hitt2023), where Republicans and Democrats now exhibit very different views toward the Court’s legitimacy. We observe this here. As Figure 5 reveals, Republicans exhibit much more diffuse support for the Court (b = 0.70, s.e. = 0.05 than Democrats (b = –0.49, s.e. = 0.03) – a difference that is significant both substantively and statistically (b = 1.20, s.e. = 0.07, p<0.001).

Figure 5. Diffuse support among respondents.

Notes: Diffuse support is measured using the Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence (Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003) measurement approach. Distribution of diffuse support in each panel is broken out by respondent partisanship (or lack thereof). Smaller values convey less diffuse support; larger values convey higher diffuse support. Full details regarding the measurement of diffuse support can be obtained in Appendix A.

Recalling that diffuse support was positively related to ranking the Supreme Court as an important issue in Study 1, these comparatively lower levels of diffuse support among Democrats suggests that it is unlikely that they may be persuaded to view the Court as more important than they already do. As such, there may be weak incentives for Democratic political entrepreneurs running congressional campaigns to expend valuable political capital reforming the Court – these lower diffuse support partisans may send only muted signals for restricting the Court’s authority, despite reform being a sympathetic cause to Democrats more generally (Badas Reference Badas2019; Clark Reference Clark2009).

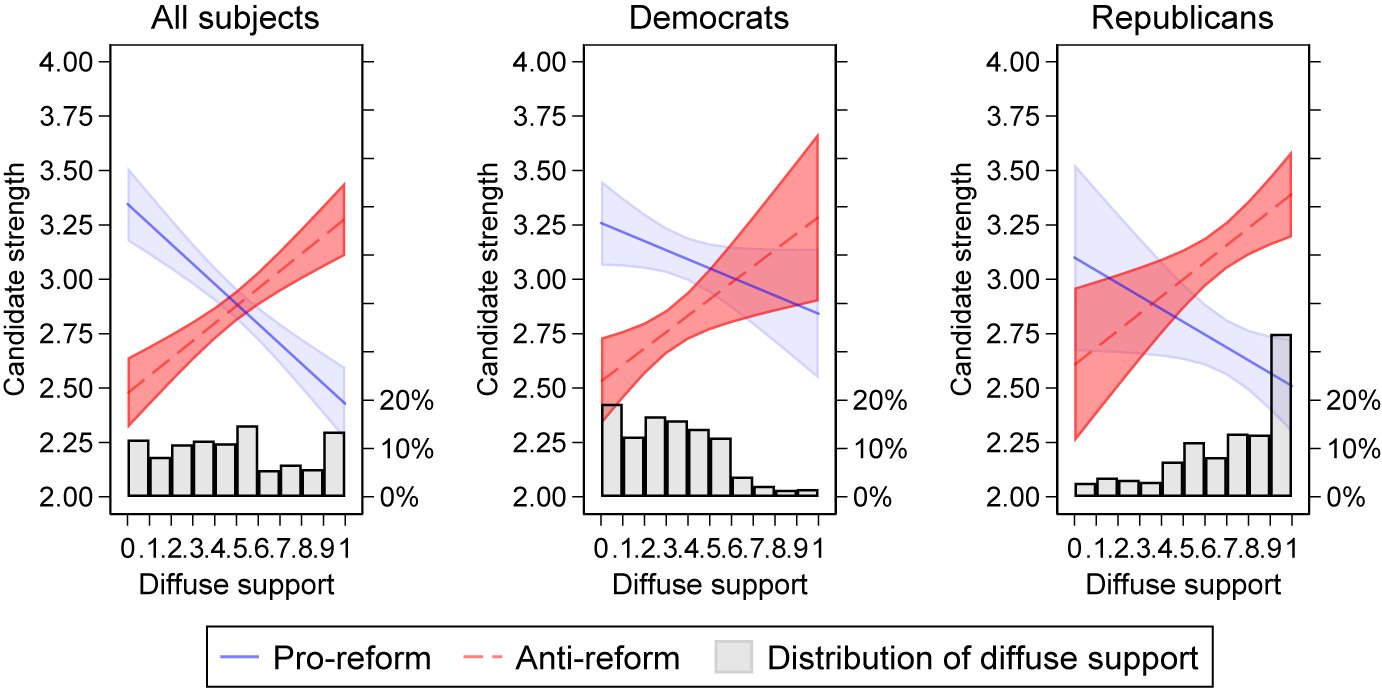

In Figure 6, we conclude our investigation of the relationships among reform messages, partisanship and diffuse support with an exploratory analysis that integrates these forces together.Footnote 18 Panel A in Figure 6 suggests that, indeed, subjects with low and high levels of diffuse support react differently to candidates’ messages about reforming the Supreme Court. Subjects with high levels of diffuse support in the pro-reform condition view the candidate as weaker compared to subjects with high levels of diffuse support in the anti-reform condition – a relationship that is reversed for individuals with low levels of diffuse support, who view pro-reform candidates as stronger.

Figure 6. Candidate support conditional upon treatment assignment, subject partisanship, and diffuse support.

Notes: Outcome is perceived candidate strength. Scores for subjects were calculated using a three-way interaction among partisanship, treatment (pro-/anti-reform), and diffuse support. Shaded bands bracketing solid- (pro-reform) and dotted lines (anti-reform) represent 95 percent confidence intervals. A histogram visualizing the distribution of diffuse support scores for subjects with a given panel have been superimposed along the x-axis.

However, Panels B and C suggest that these heterogeneous treatment effects are obscured by partisanship. In fact, the effect of diffuse support on candidate strength is channeled differently among partisans: Democrats low in diffuse support – persons who desire to see the Court’s composition changed or its powers revised – view the proreform (anti-reform) candidate positively (negatively). However, as the diffuse support increases, which presumably conveys a resistance to rather than acceptance of reform, such differences fade. Democrats high in diffuse support do not view the candidates differently. For Republicans, this dynamic is reversed. Republicans high in diffuse support view the proreform (anti-reform) candidate negatively (positively). Those differences fade as diffuse support decreases. Taken as a whole, then, diffuse support is not a monolithic property; its relation to support for electoral candidates who take varying approaches to reforming the Supreme Court is entirely conditional upon the partisan screen through which such information is filtered.

Taken together with the results from Study 1, these outcomes are not inconsequential. Diffuse support once operated as a powerful form of cross-pressure (c.f. Hillygus and Shields Reference Hillygus and Shields2008), protecting the Court against calls to reform it in ways that might return partisan benefits (Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2014). Today, however, diffuse support for the U.S. Supreme Court now exhibits a clear partisan gap (Davis and Hitt Reference Davis and Hitt2023). The inference that this gap is being driven, or at least exacerbated, by the Court’s recent decision in Dobbs strikes us as plausible (see also: Strother and Gadarian Reference Strother and Gadarian2022). However, more research remains to be done to demonstrate the durability of any such changes in the Court’s reservoir of diffuse support in the mass public. We offer these exploratory findings as early evidence that this reservoir has grown shallower on its leftmost shores. From a separation-of-powers perspective, the Court’s ability to act as a backstop against the excesses of illiberal electoral majorities (Redish Reference Redish2017) in the other branches may be imperiled by these findings because progressive citizens and elites may see little reason to voluntarily submit to the rulings of what they perceive to be an illegitimate institution. Future work should explore this possibility directly, as well as potential differences that may exist with respect to who makes these campaign appeals. Perhaps appeals made by candidates during midterms are received differently than those made during general election cycles.

Discussion and conclusion

The Supreme Court’s role in American politics has evolved dramatically over time. Whatever popular consensus regarding the role of the judiciary in the American way of life that existed during the midcentury Warren Court has been slowly replaced by a modern countermovement that appears keen on undoing many of the civil protections built during that period (Hollis-Brusky Reference Hollis-Brusky2015). As polarization increased in the late 20th century, the Court’s powers have only sharpened, complete with an unusual turn as election arbiter during the 2000 presidential election (Hasen Reference Hasen2004). Coupled with a string of highly publicized and unpopular decisions and bitter and divisive nomination battles, it is unsurprising that public opinion toward the Court has shifted in a negative direction (Pew Research Center 2022). Prior work suggests that the Court might voluntarily restrain its behavior in order to avoid being curbed by Congress as a result of this backlash (Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011; Vanberg Reference Vanberg2005). Yet in this negative and polarized political environment, the justices struck down Roe v. Wade. Why did the justices fail to constrain themselves? Will the Court face any institutional consequences for its dramatic exercise of countermajoritarian authority (Owens Reference Owens2010)?

If this backlash is to materialize, then it stands to reason that the Court must be weighing more heavily on the minds of voters (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974). In this paper, we tested that idea, but found that the Court registered only weakly in the minds of American adults compared to other salient issues like the economy, healthcare, or taxes – conceptually replicating recent research that finds that the Court is less important than other pressing issues (Badas and Simas Reference Badas and Simas2022) and that Court reform, specifically, is rarely a top political priority (Black et al. Reference Black, Owens and Wohlfarth2023). Further, candidates who take group-congruent positions on reforming the Supreme Court are not rewarded for their trouble. Our survey experiment illustrated that, while support for and opposition to reform shifts voters’ perceptions of candidates’ ideology, there is only modest affective upside to taking group-congruent positions relative to taking no position at all, although there were significant penalties associated with taking a position that does not align with the stereotypical partisan approach (Arceneaux Reference Arceneaux2008; Sheagley et al. Reference Sheagley, Dancey and Henderson2022).

In addition, by incorporating the role of diffuse support, we were able to peel back some of the underlying potential dynamics embedded in these relationships. Exploratory analysis in Study 2 illustrated diffuse support translates into varying evaluations of candidate strength, conditional upon partisanship. Those findings hint that the consequences of judicial legitimacy for electoral choice are bound by basic group memberships; in fact, treating beliefs about legitimacy as monolithic – or free from partisan biases – obscures how judicial and electoral politics are wedded together.

In past eras, high levels of Supreme Court legitimacy functioned like a classic cross-pressure (Hillygus and Shields Reference Hillygus and Shields2008). The Court was not necessarily viewed as an inherently partisan body by the public, in part because its status as an unelected body that operates as a “check” on the other branches helped legitimate its separateness from the other, more partisan branches. Notions of principled and nonpartisan processes helped to sustain high levels of diffuse support among both parties even in the face of unpopular decisions with partisan implications – resulting in perceptions that political losses were the result of nonpartisan legal reasoning (Baird and Gangl Reference Baird and Gangl2006).

Today, however, political conditions have obviously changed. Polarization is rampant and the Supreme Court has become – by its own hand – transparently partisan (Brown and Epstein Reference Brown and Epstein2023). This reputational shift has generated new, one-sided partisan calls to reform the Court. But, unlike past eras, when legitimacy might have undercut such demands, the sorting out of diffuse support by partisanship has dulled its ability to function as a cross-pressure that can sustain the status quo among partisans on the proverbial outside-looking-in. Democrats exhibit low levels of diffuse support for the Court and view political candidates who want to reform it positively; in contrast, Republicans exhibit higher levels of legitimacy and are resistant to such demands. There are few Democrats high in legitimacy and few Republicans low. The practical result is that prevailing intuitions regarding diffuse support – which predict a parallel relationship between legitimacy and demand for reform among members of both parties – no longer hold.

An emergent body of research suggests that these are tectonic institutional shifts (Davis and Hitt Reference Davis and Hitt2023; Gibson Reference Gibson2023; Strother and Gadarian Reference Strother and Gadarian2022). The well-established relationship between Court curbing and public opinion (Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011) seems newly attenuated by these changes. While the American voter juggles many competing demands, our results suggest that, when the Supreme Court becomes salient, voters’ evaluations of legislative candidates break almost entirely upon a sorting out of diffuse support and partisan orientations that fosters ambivalence among potential reformers. On the one hand, Democrats are more likely to disapprove of the Court and sympathize with demands for reform; yet, on the other hand, low levels of diffuse support ironically render the Court less important as an electoral issue. Given this development, it seems extraordinarily difficult for Congress to muster the necessary supermajorities and political will to enact Court-curbing legislation (Binder Reference Binder2015; Chafetz Reference Chafetz2017). That break is a significant challenge to the heretofore conventional scholarly wisdom regarding both Supreme Court legitimacy and for Congress’s ability to restrain an out-of-step Court.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/jlc.2024.1.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mike Nelson, Andy Stone, Eileen Braman, Vanessa Baird, and other panelists at the SPSA meeting for their excellent feedback and encouragement, as well as attendees of Colorado State University’s “R&R” brown bag series, seminar participants at Indiana University, and the editor and several reviewers for providing helpful comments that improved this manuscript.

Financial support

The authors are grateful for the National Science Foundation, grant #SES-22256543 for generously supporting the data collection used in this paper, and the YouGov team assigned to the project for expertly shepherding it through fielding.

Competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.