Introduction

Collaborative research projects involving policy makers and either academic or practical behavioural researchers are increasingly attracting attention. In 2010, the British government was the first to establish its own government unit to practically improve policy design based on behavioural insights (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Snijders and Hallsworth2018). Today, more than 200 institutions worldwide apply behavioural insights to public policy and test their application in the field (OECD, 2020). On the academic side, the publication of ‘Nudge’ by Thaler and Sunstein (Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008) ignited unprecedented interest of university researchers in partnering with public bodies in order to conduct behavioural field experiments.

The instrument that has received most attention in behavioural public policy are nudges. These interventions alter the decision environment of individuals ‘without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic consequences’ (Thaler & Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008). Hence, nudge interventions are perceived as less intrusive than other policy tools, such as setting up bans, regulations or monetary incentives. Nudges are widely used for policy design (DellaVigna, Reference DellaVigna2009; Madrian, Reference Madrian2014) with applications ranging from automatic enrolment to pension accounts (Madrian & Shea, Reference Madrian and Shea2001) over inducing energy conservation of private households (Allcott, Reference Allcott2011) to improving tax compliance (Hallsworth et al., Reference Hallsworth, List, Metcalfe and Vlaev2017). They provide an attractive tool for policy makers to address prevalent problems because implementation costs are low, the necessary changes to encourage citizens to make particular choices appear small, and nudge interventions can be tested via randomized controlled trials (RCTs) before roll-out (Einfeld, Reference Einfeld2019).Footnote 1

This study presents the first empirical investigation into the current state of collaborative research. Throughout the article, the term ‘collaborative research’ refers to the collaboration between a public body on the one hand and either academic researchers or behavioural insight teams on the other. My empirical research endeavour has the objective to describe strengths as well as pitfalls of collaborative experiments and aims to inform academia and public policy institutions alike. For the analysis, I use a novel dataset of anonymously collected insights from 70 public servants, behavioural insight team members and academic researchers with experience in collaborative research. Like Vivalt and Coville (Reference Vivalt and Coville2019), the author of this study made use of a unique opportunity to conduct a survey among conference participants. I chose the ‘Behavioural Exchange 2019 (BX2019)’, one of the largest conferences on behavioural insights worldwide. In addition to that, 12 in-depth interviews with selected experts allow for a more comprehensive interpretation of the patterns observed in the quantitative data. They moreover provide the basis to develop some practical recommendations of how to remedy the observed weaknesses. According to Mayer (Reference Mayer2006), an expert is someone who is either (i) responsible for the development, implementation or control of a way of solving problems, or (ii) has exclusive access to data regarding groups of decision-makers or the process of decision-making.

Based on the mixed-methods approach employed in this article, the study derives three main results. First, public employees have an enormous influence on the design of collaborative field experiments, specifically on developing the research question and selecting the sample. At the same time, the data of this study indicate that public employees yield clearly different priorities than researchers. This has implications for the scope and focus of the research endeavour.

Second, this study reveals that the highest scientific standards are regularly not met in cooperative experiments. Individuals cooperating with a public body experience a high degree of risk aversion in their public partner. Tentative evidence indicates that behavioural insight team members more often adjust to the needs of the public body than academic researchers. Main reason for this seems to be that academic researchers have the freedom to call off an experiment if their requirements are not met whereas behavioural insight team members are bound by contracts.

Third, the study documents that transparency and quality control in collaborative research – as manifested in pre-analysis plans, the publication of results and the measurement of medium or long-term effects – tends to be low.

Based on the findings presented in the article, the study makes several suggestions for improvements, among them establishing a new behavioural insights working paper series and a matchmaking platform for interested researchers and public bodies since data from the interviews suggests that scientific standards increase when academic researchers are involved as partners. With respect to processes within the public bodies, internal guidelines specifying the authorized ways of collaborative experimentation and cooperation with other public institutions could facilitate cooperative research. Moreover, a co-funding by foundations or non-profit organizations would support public bodies low on resources and increase independence of public employees from political influence and a too strong agenda of the public institution.

The present study contributes to the small body of literature that examines the work of behavioural insight teams and collaborative experiments with public partners from a meta-perspective. While a large number of papers investigate the effectiveness of different nudges (see the systematic reviews by Hallsworth (Reference Hallsworth2014), Andor and Fels (Reference Andor and Fels2018), and the cost–benefit analysis by Benartzi et al. (Reference Benartzi, Beshears, Milkman, Sunstein, Thaler, Shankar, Tucker-Ray, Congdon and Galing2017)), not many studies take such a meta-level approach. As an exception, Sanders et al. (Reference Sanders, Snijders and Hallsworth2018) discuss complications, challenges and opportunities for the work of the British Behavioural Insights Team (BIT). They also touch upon some general questions related to cooperation with public partners. In his response comment, Delaney (Reference Delaney2018) raises the general question of how professional standards can be ensured in the quickly growing field of behavioural scientists, given that many of them nowadays are practitioners mainly working in a consultancy capacity. Such deliberations help assess the current state of affairs in collaborative research. Yet up to now, no systematic empirical description is available.

Moreover, the article provides a contribution to the literature on which kind of evidence is used for policy advice (Sanderson, Reference Sanderson2003; Sherman, Reference Sherman2003; Sutherland & Burgman, Reference Sutherland and Burgman2015; Head, Reference Head2016). Collaborative experiments between a public body and an external cooperation partner should be under special scrutiny since they are specifically designed to inform policy decisions. As Karlan and Appel (Reference Karlan and Appel2018) put it: ‘A bad RCT can be worse than doing no study at all: it teaches us little, uses up resources that could be spent on providing more services (even if of uncertain value) ( . . . ), and if believed may even steer us in the wrong direction.’ This study puts the topic of generating evidence-based policy recommendations by experiments involving a public partner on the agenda and documents that the evidence produced by these studies may systematically differ from other evidence available.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: First, I outline the methodology of the quantitative and qualitative data collection. Then the first main result is presented by taking a closer look at the role of public employees as gatekeepers in collaborative research. The following section ‘Scientific standards and risk aversion’ reports data on the second main result regarding compliance with high scientific standards. Presenting the third main result, the next section focuses on transparency and quality control in collaborative experiments. After discussing remedies for some of the perceived shortfalls, the final section concludes.

Data

The present study applies a mixed-methods approach, a class of research where the researcher combines quantitative and qualitative research techniques into a single study (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, Reference Johnson and Onwuegbuzie2004) in order to ensure breadth and depth of understanding, and for corroboration (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Onwuegbuzie and Turner2007). For this, I apply a two-stage explanatory design: the quantitative data informs the qualitative data selection process. This design has the advantage that observations from the quantitative data allow to specifically pinpoint relevant data in the qualitative data collection process (Almalki, Reference Almalki2016).

Quantitative survey

For the first stage in the mixed-methods approach, I designed an anonymous 5 min-questionnaire, which was answered by in total 70 participants of the ‘Behavioural Exchange 2019 (BX2019)’ – conference in London. Like Vivalt and Coville (Reference Vivalt and Coville2019), I made use of such a unique opportunity to conduct a survey among participants of a professional gathering. According to its organizers, at BX2019, about 1200 of ‘the world's leading policy-makers, academics and practitioners gathered to explore new frontiers in behavioural science’ (BIT, 2019).Footnote 2 The sampling of survey participants was conducted in a randomized manner. For this, I approached individuals at many different times and locations during the two conference days 5–6 September 2019 and distributed the pen-and-paper questionnaire in person. A potential sampling bias could arise if certain subgroups from my target population were not present among conference attendees (Krumpal, Reference Krumpal2013). Yet as my study specifically focuses on academic researchers, behavioural insight team members and public servants, and all three groups are represented in the survey, this seems unlikely.Footnote 3

Participants had three options of returning the completed form: either directly in person to me, via email, or in one of the boxes placed at the entrance hall of the conference venue. After the conference, the questionnaire was moreover sent out as online survey via www.onlineumfragen.com, a Swiss survey platform, in order to increase sample size.Footnote 4

The questionnaire comprised 12 questions (see Supplementary Appendix A) and had been pilot-tested among researchers with experience in collaborative research. While questions 1 to 4 refer to general aspects of collaborative experiments which were posed to all survey participants, the rest of the survey focuses on own experiences. Consequently, the group of those who indicated in question 5 to have no own experience in collaborative research was at this stage directly navigated to the final question asking for their affiliation. During the analyses of those questions referring to own experiences in collaborative research, only respondents are included who have at least conducted 1–2 experiments themselves. For clarification regarding the respective numbers of relevant respondents, all tables presented in this article depict the absolute number of respondents next to the relative share.

Response rates to the survey were 28.3% (43 of 152 handed out survey forms) and 10.4% (27 of 260 individuals contacted via email), respectively. Unfortunately, I have no information about non-respondents. In case systematic differences between respondents and non-respondents occurred, the study's validity would be threatened by non-response bias (Krumpal, Reference Krumpal2013). However, apart from time restrictions (which would affect all groups of conference attendees similarly), the most probable motivation to participate in the survey is that responders were particularly affected by the topic, while non-responders might not have seen much relevance of the questions for themselves. Since it is not the aim of the survey to provide a representative picture of opinions on collaborative research in general but rather to focus on personal experiences individuals made during their collaborative research, this potential self-selection does not seem to limit the data's scope to answer the research question. Moreover, to prevent social desirability bias, all survey questions have been thoroughly checked. None of them gives reason to suspect that ‘due to self-presentation concerns, survey respondents underreport socially undesirable activities and overreport socially desirable ones’ (Krumpal, Reference Krumpal2013, p. 2025). By choosing two of the least intrusive data collection modes – a self-administered paper-and-pencil questionnaire during the conference and a web-survey afterwards – one of the main driving factors for social desirability bias was kept at the minimum.

Respondents’ characteristics

This section presents respondents’ characteristics from of the anonymous survey. Out of 70 survey respondents, 60 (86%) provided information about their affiliation (Table 1).Footnote 5 Some 32% of them are academic researchers, another 45% public employees – employed either in the capacity of a public servant or as a member of a behavioural insight team, and 23% work for a private company.Footnote 6

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Note: Out of 70 respondents, only 60 provided information about their affiliation. The percentages in brackets refer to the share in this subgroup.

Table 1 also provides an overview of the number of experiments which respondents have conducted. It shows that among public employees a much smaller share than among academic researchers has no own experiences with experiments on behavioural insights. Almost half of the sample of public employees are considerably experienced: they have conducted at least three own experiments. This reflects that all employees from behavioural insight teams are included in this subgroup, and their job mainly consists of designing and implementing experiments. In addition to that, public employees most likely only attend an expert conference when it is practically relevant for their work, whereas for academics it is much more common to also choose a conference in order to get a good overview about current research on a topic even if oneself has not conducted own research in that field yet.

Most survey respondents indicate to have conducted experiments in Anglo-Saxon countries like the UK, the US, Australia, Canada or Ireland, with an overwhelming majority of experiments being located in the UK. This might be due to the fact that the BX2019-conference was organized by the BIT and many of the behavioural insight team members in my sample likely stem from the BIT. The second group of countries, in which experiments were conducted, includes European countries like the Netherlands, Denmark, Lithuania, Finland, Belgium, Germany and France. Respondents also reported a few collaborative experiments in Afghanistan, Guatemala, Philippines, Kenya, Sierra Leone and Georgia.

In terms of policy fields of own experiments, two fields clearly stand out: education (18) and health and nutrition (16) (see Figure 1, right column). In the second tier, taxation (9), consumer protection (9) and energy and environment (8) attracted frequent attention. The least often experiments were conducted in agriculture (2).

Figure 1. Policy fields: relevance ranking and own experiments.

I also asked respondents to rank from 1 to 5 which policy field they consider most important to test behavioural insights. As the method of scaling, I chose the Borda count (Borda, Reference Borda1784) which is applied worldwide in elections and sport competitions. This method is recommended for cases when one wants to produce a combined estimate of the best item, instead of discarding information by just counting which item was put on rank 1 most often. Under the Borda count, points are assigned to items based on their ranking position: 1 point for last choice, 2 points for second-to-last choice and so on. Consequently, in my study, rank 1 was assigned 5 points, rank 2 received 4 points and so on. After the ranking, the point values from all survey participants were totalled, and the item with the largest point total was assigned the overall rank 1 of the full sample. As the last step, in order to make total points comparable between subgroups and the full sample, I standardized the number of total points by the maximum number of points that was achievable if every participant in the (sub)group had ranked this item on rank 1. The maximal sum of points from 70 valid responses in the full sample was 350.

Interestingly, for some policy fields, the relative frequency of own experiments stands in contrast to what respondents themselves assess as most relevant fields to test behavioural insights. While health and nutrition together with education make up the top 2 in both rankings, energy and environment is assessed as much more relevant than it is mirrored by actual experiments. Especially when compared to the relevance assessment of consumer protection, which has the same number of own experiments but ranks much lower in the relevance assessment, energy and environment seems to be under-researched. The contrary is true for taxation and foreign relations. While they achieve the second tier of policy fields with most frequently conducted experiments, they have not been attributed much relevance in the assessment ranking. Based on relevance assessments, foreign relations score the next-to-last rank.Footnote 7 However, it is worth noticing that for some respondents, the formulation of the question might have installed a lower bound due to two reasons: First, respondents were asked to name their top 5 according to the frequency of own experiments. For those who conducted experiments in more than five policy fields, certain policy fields might be underrepresented in their answer. Second, if a respondent conducted more than one experiment in a certain field, it can still only be counted once since I have no data about the number of experiments in each respective policy field. The same is true for the question of which interventions have been tested.

For interventions tested in own experiments, a top 5 emerges (see Figure 2, right column): social norms (20), simplification (16), increase in ease and convenience (16), letter design (15), and – with a little distance – reminders (12). All these interventions can be considered as minimally intrusive. They would not meet much resistance when discussed with policy partners, potentially in contrast to nudges like eliciting implementation intentions, disclosure, or changing the default rule, which attracted much less attention by survey respondents. This pattern fits to what has been documented in the literature elsewhere. For example, in more than 100 trials conducted by the two main behavioural insight teams in the US, a change of default settings was only tested twice, both in one trial (DellaVigna & Linos, Reference DellaVigna and Linos2020). However, when it comes to the relevance assessment under the Borda count, the respondents of this study clearly see default rules as the most important intervention to be tested. Defaults rank substantially before simplification, increase in ease and convenience, and social norms and can hence be considered under-researched with respect to the respondent's own priorities (see Figure 2, left column). Interestingly, the contrary is true for reminders and letter design: Both interventions do not achieve a high position in the assessment ranking but have been researched in own experiments quite frequently.Footnote 8

Figure 2. Interventions: relevance ranking and own experiments.

Qualitative interviews

In the second stage of the mixed-methods approach, I collected insights from selected experts by semi-structured interviews. Such an approach is recommended when the study's aim is to gain sophisticated insights into aspects of social reality (Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, Reference Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik and Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik1992) and wants to capture nuances that cannot be detected by a quantitative approach (Glennerster et al., Reference Glennerster, Walsh and Diaz-Martin2018).

Non-probabilistic purposive sampling

The sampling followed a non-probabilistic purposive sampling approach: ‘particular settings, persons or events are deliberately selected for the important information they can provide that cannot be gotten as well from other choices’ (Maxwell, Reference Maxwell2012, p. 235).Footnote 9 Since the aim was to fully understand the patterns discovered by the anonymous survey and to shed some light on the reasons and mechanisms behind the apparently different experiences of academic researchers, behavioural insight team members and public servants in collaborative research, I purposefully selected interview partners who satisfied the following criteria: (i) they belong to one of the three target groups and (ii) they have personal experience with at least one collaborative field experiment testing behavioural insights applied to policy design. With the exception of two non-responders and one refusal due to time reasons, all of the contacted experts either agreed to be interviewed or referred me to a colleague who would speak to me instead.

The final sample consists of 12 interview partners who belong in similar shares to the three target groups (see Table 7 in Supplementary Appendix C).

As recommended in the literature, I started the sampling inductively and increased sample size until theoretical saturation was achieved (Guest et al., Reference Guest, Bunce and Johnson2006). Theoretical saturation refers to the point at which additional data does not bring about new properties for a category. When a researcher sees similar observations over and over again, empirical confidence grows that this category is saturated (Glaser & Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967). The observation that saturation occurs at a sample size of 12 is supported by an experimental test by Guest et al. (Reference Guest, Bunce and Johnson2006): They find that ‘clearly, the full range of thematic discovery occurred almost completely within the first twelve interviews’ (Guest et al., Reference Guest, Bunce and Johnson2006, p. 66).Footnote 10 In my mixed-methods study, the interviews provided the second stage of data collection to corroborate and explain findings discovered by the quantitative survey. The included interview partners, even though with different professional backgrounds, can hence be considered as a particular group of experts, namely individuals who gained personal experience in collaborative research.

Semi-structured interviews

For the interviews, I used a semi-structured approach: a blend of closed- and open-ended questions (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Newcomer, Hatry and Wholey2015), sometimes accompanied by ad-hoc follow-up questions to let the interviewee further elaborate on aspects that come up during the interview (Ebbecke, Reference Ebbecke2008). Such a flexibility is recommended in order to capture the full range of the topic (Bock, Reference Bock and Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik1992). The questions were asked along one of three interview guides, each of which was specifically developed for the respective target group (researchers, behavioural insight team members, public servants) (see Supplementary Appendix D). To facilitate documentation, all interviews were recorded and transcribed. The interviews addressed the following topics: personal details, motivation for collaborative research, influence of public employees, the role of behavioural insight teams (only for researchers and behavioural insight team members), means of quality control and potential ways forward.

Thematic analysis

I analysed the interview transcripts by using a categorizing strategy and followed the six phases of thematic analysis as suggested by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006): familiarizing oneself with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes and producing the report. Initial codes were the broad topics discovered by the survey data. As themes, I identified aspects that captured something important in the data in relation to the research question. A theme would ideally be mentioned several times across the dataset but did not have to in order to be relevant (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Goal of this procedure is to identify, analyse and report patterns across the dataset rather than within an individual interview. Categorizing helps to develop a general understanding of what is going on (Maxwell, Reference Maxwell2012).

The identified themes guided the write up of those parts of the study which refer to the qualitative interviews. As recommended by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006), I chose vivid, compelling extract examples from each theme to be included in the article. All direct quotes have been authorized by the interviewees. Each of them consented to be named with full name and position.

For validation, the full article was sent to the interview partners after analysis and write-up was completed. None of them requested any changes. According to Maxwell (Reference Maxwell2012), such a respondent validation is the single most important way of ruling out misinterpretation as threat to validity.

Public employees as influential gatekeepers

In this section, the first main result is presented. The data of this study reveal that public employees yield a great influence on collaborative research, specifically on developing the research question and selecting the sample. At the same time, the study documents that public employees follow different priorities in collaborative research than academic researchers. This has implications for the scope and focus of the research endeavour.

Influence on study design

Development of the research question

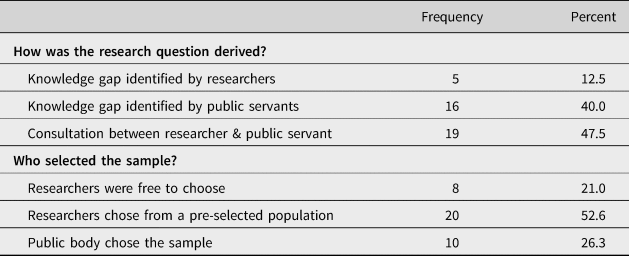

Asked how the research question in their collaborative research was derived, only a small minority (13%) of respondents indicated that a knowledge gap identified by the researcher was the starting point (see Table 2). In contrast, 40% reported that a knowledge gap identified by the public body has played this role, and another 48% referred to consultations between the researcher and the public body. This matches results from an earlier survey by Pomeranz and Vila-Belda (Reference Pomeranz and Vila-Belda2019) which focused on collaborations with tax authorities. They find that in 40% of cases the research idea emerged from jointly exploring topics of common interest between researchers and their public partner.

Table 2. Research question and selection of the sample

Notes: Values may sum up to less or more than 100% due to rounding. Of the 70 survey participants, only those with own experiences in collaborative research were asked these questions.

All qualitative interviews confirmed that the public body has a decisive influence on designing the research question. As Ruth Persian (Reference Persian2020) clearly puts it for studies conducted by the BIT: ‘The research question in a way is set by the public sector partner.’ This view is shared by Jaap Drooglever (Reference Drooglever2021) from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Kingdom Relations: ‘The municipalities decide in the end. They are responsible if something goes wrong, so that means that they look very closely on what the set-up is and if it fits their standards.’ Academic researchers like Christian Gillitzer (Reference Gillitzer2020) made similar experiences in collaborative research: ‘This was more of a partnership where the ideas and proposals were directed by the Australian Taxation Office: they had a business need and something they wanted to be evaluated. Our scope and role were to refine and design the intervention such that it could be tested scientifically.’ ‘In my experience, it works best when they come to you and they want to do something’, Johannes Haushofer (Reference Haushofer2021) from Stockholm University confirms. ‘There is openness for suggestions, but it's within a pretty narrow parameter space.’

While many researchers in academia aim to influence public policy by publishing their study results, researchers in collaborative research experience it the other way round: ‘impact comes first’ (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Snijders and Hallsworth2018, p. 156). ‘That's a key thing that I always stress to people if they want to start working with an institutional partner: to make sure you listen to what they care about. I look at it like a Venn diagram of the things that are academically relevant and publishable and the things that are relevant for the policy partner’, Dina Pomeranz (Reference Pomeranz2020) from Zurich University says.

Yet, there also seems to be some scope for researchers to increase their influence over time. Paul Adams (Reference Adams2020), a former manager of the behavioural insight unit at the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in the UK, recounts: ‘In some of the earlier trials, the policy interventions were mostly designed by the policy makers. Over time, when results were not as positive as expected, we started to develop a bigger role earlier in the process, and used some other techniques to help design and develop more effective interventions.’

Selection of the sample

With respect to selecting the sample, the quantitative data again document a great influence of the public body. As Table 2 depicts, only one fifth of respondents (21%) state that the researchers were free to choose any sample from the target population. In contrast, public servants at least pre-selected the sample in about 80% of studies.

This is corroborated by some qualitative interviews. ‘There was a trend in all the trials that went ahead that over time the samples tended to get smaller and smaller and smaller. So there was a bit of an incentive for the researchers to go in and overbid on the sample size to the expectation that there would be a reduced size by the time that the actual intervention went into the field’, Christian Gillitzer (Reference Gillitzer2020) from Sydney University recounts his collaboration with the Australian Taxation Office. ‘One of the dilemmas is that there is a trade off between really new designs to experiment and the scale at which you can do it and therefore the scientific control you have. If you do something really innovative, but it's only in one or two spaces, maybe that is how you make a big step from “how we did it” to “how we can do it”. But on the other hand, you don't have a lot of evidence supporting whether that was really effective’, also Jaap Drooglever (Reference Drooglever2021) from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Kingdom Relations reports.

On the administrative side, the interviewed public servants were despite their adherent interest and experiences in behavioural experiments very aware of their organization's limited expertise in experimental design and the current state of research. ‘What we did at first was to realise that we were not the specialists, that we were interested in the field and can read about it. But I think it's important to say: Other people are the experts, and then to use that expertise’, Jaap Drooglever (Reference Drooglever2021) summarizes. ‘The advantage is definitely the level of expertise we get. We don't have anyone employed at the city of Portland who is a behavioural scientist or has that level of expertise, that connection to the ongoing, rapidly evolving field of research’, Lindsey Maser (Reference Maser2020) says. Thomas Tangen (Reference Tangen2020) from the Norwegian Tax Administration consents: ‘All the very young academics we have hired are from different universities. But I still think it is important to have a close relationship with people outside the administration.’

Differing priorities

The great influence of the public body on study design might have meaningful consequences if priorities of public employees and researchers in testing behavioural interventions substantially differed. In these cases, collaborative research with a public partner would lead to a systematically different research focus than other academic work, potentially along a research agenda that is sub-optimal (Levitt & List, Reference Levitt and List2009).

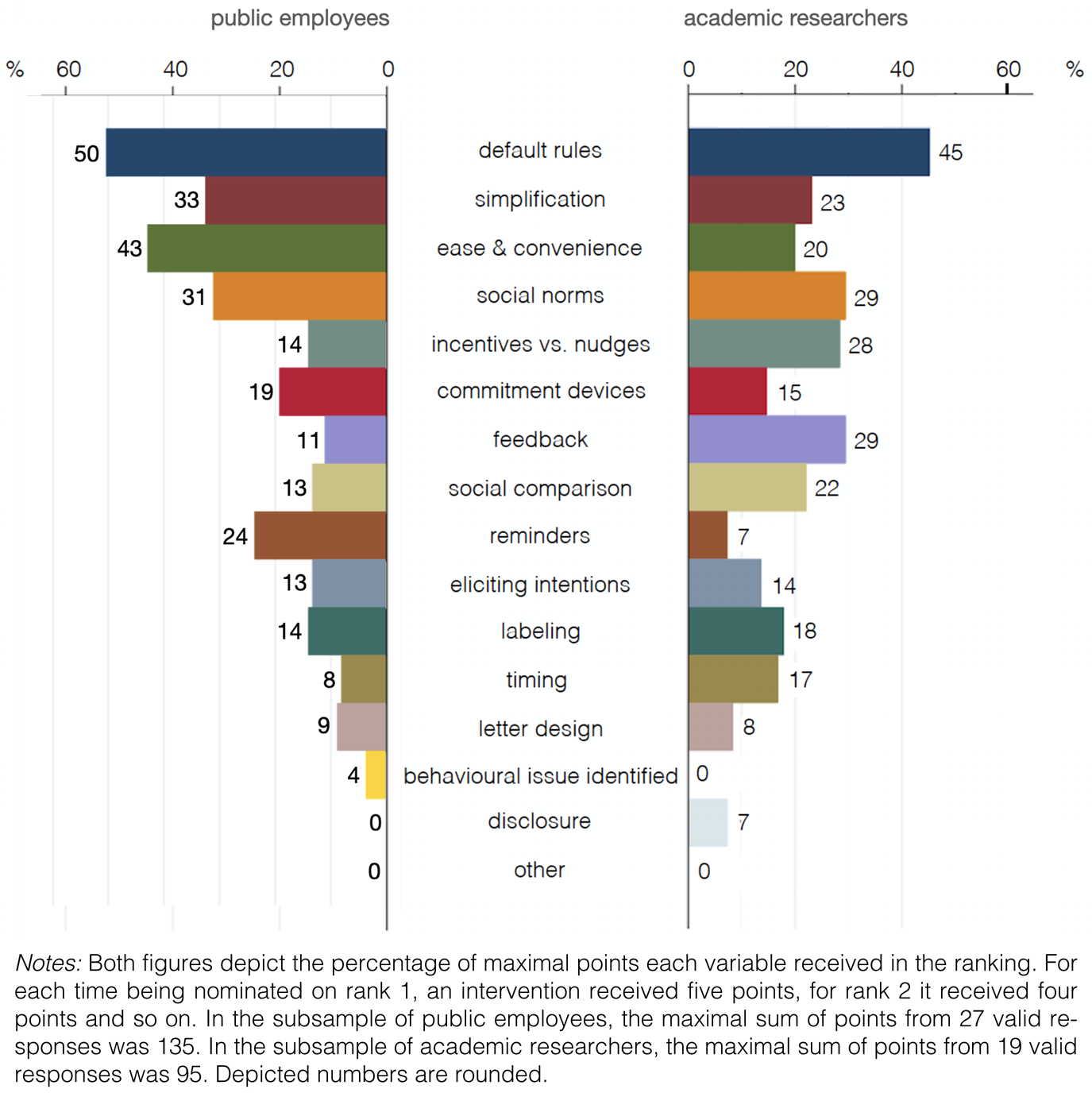

Interventions to be tested

This study shows that academic researchers and employees from a public body do yield such different priorities regarding the interventions to be tested (see Figure 3). While both groups agree that changing the default rule, one of the most effective but also most controversial nudges (see Reisch & Sunstein, Reference Reisch and Sunstein2016; Sunstein et al. Reference Sunstein, Reisch and Rauber2018; Jachimowicz et al., Reference Jachimowicz, Duncan, Weber and Johnson2019), is the most important intervention, assessments differ for the other interventions in their respective top 5.

Figure 3. Ranking of interventions – subsamples public employees and academic researchers.

For public employees, ‘increase in ease and convenience’ is the second most important intervention (43% of maximal points), whereas among academic researchers this intervention does not even achieve their top 5. The same is true for reminders, which receive 24% of maximal points (rank 5) among public employees but score very low with academic researchers (7% of maximal points).

Academic researchers, on the other hand, assess several interventions as much more relevant than public employees: feedback (29% vs 11%) as well as ‘financial incentives versus nudges’ (28% vs 14%). Both interventions make it into the researchers’ top 5 but are not ranked highly by public employees. In addition to that, timing (17% vs 8%) and disclosure (7% vs 0%) are considered more important by researchers than by public employees. Given the great influence of the public body on study design, this will likely lead to these interventions being under-researched in collaborative experiments. This interpretation was confirmed by several qualitative interviews. One interviewee put it in a nutshell: ‘We did have early on a conference where we met with many senior people from the public partner. There we came on with proposals. And they were receptive. But ultimately the things that went ahead were dictated primarily by their business needs.’Footnote 11

Policy fields of interest

Interestingly, with respect to policy fields, less pronounced differences can be observed. Researchers and public employees overall agree that health and nutrition as well as education rank on the first two spots, followed with some distance by energy and environment, work and pension, and consumer protection (see Figure 4). This mirrors the pattern observed in the full sample with the sole modification that in the full sample data, consumer protection ranks before work and pension (see Figure 1, left column). When compared with the AEA RCT registry, the most popular database in economics to pre-register an RCT, one can also observe that the pattern closely fits those policy fields in which most RCTs have actually been conducted.Footnote 12

Figure 4. Ranking of policy fields – subsamples public employees and academic researchers.

Yet there are also some differences between the two groups. While public employees assess transportation as an important policy field, this field is not deemed very important by academic researchers (20% vs 14%). On the other hand, public finance (7% vs 18%) is considered relatively more important by academic researchers than by public employees.

Overall, there seems unity that defence, foreign relations and agriculture are not very relevant for testing the application of behavioural insights. However, in practice, respondents from the sample indicated to have conducted own experiments in these policy fields: foreign relations were nominated seven times, agriculture two times and defence at least once (see Figure 1).Footnote 13

Motivation for collaborative research

Several interviewees explicitly mention that the perspectives of academic researchers differ from those of the public body while in the quantitative data differences in the motivation for collaborative research are not clearly observable (Table 3). This might be due to the fact that the in-depth interviews were able to uncover some aspects which were not listed as answering options in the survey. ‘I have realized when collaborating with academics quite often, because interests are different, they might be more interested in testing a theory or in finding interesting results that can be published nicely. We got a few projects where we take more the research angle, but ultimately if I have to run the 50th social norms tax trial, it will probably not be intellectually stimulating but if I think that's actually the most effective thing, then that's ultimately what I would do’, Ruth Persian (Reference Persian2020) from BIT explains. Johannes Haushofer (Reference Haushofer2021) describes the same phenomenon from the academic point of view: ‘Public partners are often interested in a quick turnaround and quick results, and they're maybe less interested in understanding mechanisms. They just want to know if it works. As a researcher, you care a lot about why it works. You want a really clean design. That's often not a priority of the public partner.’ Wilte Zijlstra (Reference Zijlstra2020) from the internal behavioural insight team at the Authority for the Financial Markets in the Netherlands adds: ‘We're not a university. Our main task is to promote fair and transparent financial markets. We do research together with academics. But research is not our only aim.’

In sum, while the public body is interested in finding out what works, researchers moreover want to dive into the whys of the causal relationship (Czibor et al., Reference Czibor, Jimenez-Gomez and List2019) in order to inform ongoing theoretical debates (Christensen & Miguel, Reference Christensen and Miguel2018). In clinical research, these categories are used to distinguish pragmatic trials from explanatory trials with the former reportedly being most attractive for policy makers (Patsopoulos, Reference Patsopoulos2011). On the upside, the documented great influence of the public body ensures that the research endeavour is designed in a way that it will create substantial political interest and impact policy decisions (Karlan & Appel, Reference Karlan and Appel2018). On the downside, it gives rise to confirmation bias.

Table 3. Greatest advantage of collaborative research

Notes: The full sample also comprises of those respondents who did not indicate their affiliation. Values may sum up to less or more than 100% due to rounding. Absolute numbers in brackets.

a In the open text-field option, some respondents enlisted reasons that could be summarized into a new category: creating direct benefits of research for policy institutions and the wider public. This was not provided answering category in the questionnaire.

This bias occurs when the motivation for evaluating a programme or a new policy is to produce external evidence for observations that have been already made.Footnote 14 If this was the case, the research endeavour would be designed in a way to favour expectancy congruent information over incongruent information (Oswald & Grosjean, Reference Oswald, Grosjean and Pohl2004) and not to search for the true underlying behaviour.

Constraints within the public administration

To gain a deeper understanding of the constraints that public employees are facing, the qualitative interviews also addressed the question what reservations interview partners met within their public administration while pursuing an experimental test of interventions. In the following, their answers are presented along the themes that occurred during the interviews.

Time constraints

The top answer, mentioned by every interviewee, was: time constraints. This comprises two aspects: First, experiments take time until they produce results, and second, they need a lot of time and effort invested by the people running them. Thomas Tangen (Reference Tangen2020) from the Norwegian Tax Administration describes the tradeoff: ‘Often it is like “we have a good idea, let's implement it”. So that's one of the main issues with academia, it takes so long time before you get the results.’ Paul Adams, formerly Financial Conduct Authority in the UK, confirms: ‘Within every organization there is a time pressure and people like to get things done quickly. Field experiments often take more time. That was often the main discussion point with our policy making colleagues.’ Johannes Haushofer (Reference Haushofer2021) from Stockholm University sees the reason in election cycles: ‘Experimentation is often hard for policymakers because they face pressures that don't lend themselves to that kind of approach. They need to get reelected next year. And the three years it takes to run an RCT is too long for them and too risky.’

Ruth Persian (Reference Persian2020) from the BIT made the following observations: ‘I think for them it's about how much effort goes into everything. “Why do we have to think about everything so many times? Why do we have to make sure everything is randomized perfectly, and then we have to go back to the data again because there was a mistake . . . ?” I think it's this planning, this being very very detail oriented upfront. While they would prefer just doing something, just sending something out and see.’ This view is shared by Helen Aki (Reference Aki2021) from the Ministry of Justice in New Zealand: ‘People just trust the available knowledge and just want run with it. They don't want to invest the effort and the time that goes with having to set up trials and the extra work for people doing that. When you're actually running trials, sometimes it can take six months, 12 months to get a result. And that's often not good enough. People want to know now.’

Since ‘testing takes more time and is not expected yet’ (Maser, Reference Maser2020), incentives for public servants are low. Some would go so far as to just implement an intervention even though it could have easily been tested before. Even after the decision to test a new policy was made, the implementing staff may face competing priorities with respect to their day-to-day job and the new tasks the study brings about (Karlan & Appel, Reference Karlan and Appel2018). Helen Aki (Reference Aki2021) knows examples of that: ‘Often the types of work that we do within the justice sector, it's all about trying to make it better for the defendant that's going through the process, or the victim. It doesn't actually make it better for the staff member. Sometimes it can make their job harder.’

Involvement of many different actors and departments

Those public servants who bought into the idea of running a trial still need to involve a lot of people within their administration: their direct superiors and the colleagues who are affected by the implementation, the IT department, the legal department, the communications department, to name just a few. ‘Yes, it's a bit of bureaucracy. But it's also people's declarations. This is real. So you have to be very thorough. You have to do a proper job. You have to make it right’, Thomas Tangen (Reference Tangen2020) from the Norwegian Tax Administration describes. BIT-director of research Alex Sutherland (Reference Sutherland2020) sees a main task of external cooperation partners in making it maximally easy for the public partner: ‘The emphasis is really on the evaluator to reduce the burden as much as possible on those you are working with. For example, by relying on administrative data, data that is collected anyway, rather than requiring a battery of 20 tests to be done for an outcome.’ Dina Pomeranz (Reference Pomeranz2020) from Zurich University adds: ‘It is very helpful if there is at least someone within the partner organization that has as much excitement and interest in doing this study as the researchers. Then you become a team and can present this to the director of the institution, and help each other to make sure that it's academically sound but also interesting for the leaders of the organization.’

High internal turnover

However, having won the trust of certain public servants does not mean that the experiment will go along as planned. ‘You need to have a champion on the inside. That can be risky to the extent that if you don't know that person really well, they might change their mind or they might leave their job and then someone else comes in who doesn't have the same priorities’, Johannes Haushofer (Reference Haushofer2021) from Stockholm University explains. Christian Gillitzer (Reference Gillitzer2020) from Sydney University recounts similar experiences: ‘One of the things that we faced is that there is very high turnover internally. We had to deal with different people on a frequent basis. So that made it a little bit difficult that some of the conversations which had gotten going then had to start again.’ This can even lead to cancelling entire projects that were already agreed upon, Dina Pomeranz (Reference Pomeranz2020) says: ‘When working with large institutions, changes in the environment or in the leadership are likely to occur. There can, for example, be an unexpected change in the head of the authority who may not share that priority. So there is a substantial risk that in the middle of a research project somebody comes in and says: “Actually, we're not going to finish the study”.’

Outdated IT systems

Another substantial constraint for collaborative experiments seems to be outdated IT systems within the administration. Three out of four interviewed public servants mentioned that external communication to citizens has to run via databases which are not suited for changing correspondence for different test groups (Maser, Reference Maser2020; Tangen, Reference Tangen2020; Aki, Reference Aki2021). ‘Our systems are not set up in a way that enables good experimental design. So we want to change something but the IT system only allows one thing or another, so you can't set up RCTs’, Helen Aki (Reference Aki2021) from the Ministry of Justice in New Zealand describes. This creates yet another internal bottleneck: ‘We've been working with the department staff, but they are reliant on our technology department to help them access their data and, when necessary, edit databases that auto-generate communications. And our technology department doesn't have time to help them or sometimes the databases are so old that it's difficult to try and change them. And obviously to try and run that experiment by having staff manually send out a letter would be prohibitively time consuming’, Lindsey Maser (Reference Maser2020) from the City of Portland recounts. ‘We have to think more like a web-administration’, Thomas Tangen (Reference Tangen2020) points towards a way into the future. ‘When you have an internet side, you are running experiments all the time. But on our systems, it's not like that. Our system is quite old. And security is important.’

Ethical concerns

On a more principal level, also ethical concerns need to be addressed. ‘There is number of different concerns. First the general idea of experimenting on people but then also: Why are we preventing a certain group of the population from an intervention that we are thinking is beneficial?’, Ruth Persian (Reference Persian2020), senior advisor at the BIT, recounts. Johannes Haushofer (Reference Haushofer2021) from Stockholm University met similar reservations: ‘Randomization is something that many policy makers shy away from, it seems unethical at first glance. Not knowing the researchers is another obstacle, if you don't know whether to trust these people and if they're going to deliver on the things that they promised.’ ‘For the municipalities, the practical result in the neighbourhood is the most important. These are their inhabitants. There are not guinea pigs. They are real people. So they have to be and want to be really respectful toward them’, Jaap Drooglever (Reference Drooglever2021) from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Kingdom Relations in the Netherlands says. Thomas Tangen (Reference Tangen2020) from the Norwegian Tax Administration consents: ‘Experimenting with people's declaration, you have to have your ethics in place.’ Consequently, the public partner needs to get convinced that the experimental approach is ethical, legal, and that necessary insights cannot be derived by other econometric techniques (Gueron, Reference Gueron, Banerjee and Duflo2017).

Scientific standards and risk aversion

As second main finding, the data from the quantitative survey and the qualitative interviews reveal that the highest scientific standards are regularly not met in cooperative experiments. Individuals cooperating with a public body experience a high degree of risk aversion in their public partner. Especially members from behavioural insight teams seem to perceive a pressure to accommodate the needs of the public body, either due to employee or to contract obligations.

Scientific standards

The anonymous survey of this study unveils that in cooperative research the highest scientific standards are regularly not met. A majority of respondents indicates that they had to move away from an ideal scientific approach at least 50% of the time. One quarter of respondents experienced this even in the majority of cases or always (see Table 4).

Table 4. Scientific standards and risk aversion

Notes: Respondents were asked (i) how often they had the impression they had to move away from an ideal scientific approach in order to accommodate the requirements of their cooperation partner, and (ii) how frequently they had the impression that their research opportunities were limited by a high degree of risk aversion in the public cooperation partner in comparison to experiments with other partners. The full sample comprises of 70 respondents, ten of whom did not indicate their affiliation. Only survey respondents with own experiences in collaborative research were asked these questions. Values may sum up to less or more than 100% due to rounding. Absolute numbers in brackets.

a In the online survey, respondents who indicated to be a public servant were not asked these questions. Answers in the subsample of public employees hence mainly stem from members of a behavioural insight unit.

b The answering options ‘never’ and ‘always’ include the statement that the respondent only conducted experiments with public partners.

Moreover, there is tentative evidence that public employees, in particular behavioural insight team members, feel the pressure to accommodate the needs of their cooperation partner at the cost of high scientific standards more strongly than academic researchers. While the subsample of academic researchers is evenly split between those who report that they had to move away from an ideal scientific approach never or only in the minority of cases, and those who did this at least 50% of the time, the proportions within the subsample of public employees are clearly different. More than 70% of public employees indicate to have experienced such a pressure at least 50% of the time, while only 30% report this for a minority of cases or never. The answers of public employees to this question are mainly driven by members of behavioural insight teams, since a sample split in the online survey prevented respondents who had indicated that they were a public servant from getting asked that question at all.

For behavioural insight teams, two types can be distinguished: (i) internal units dedicated to applying behavioural insights within their organisation, and (ii) external units like the BIT which started as a British government institution and became a social purpose consulting company in 2014 working for public bodies all over the world.Footnote 15 Since both types of behavioural insight units are on the payroll of the public body, they are more closely connected to its interests than external actors like academic researchers.

This observation was also confirmed by the qualitative interviews. Paul Adams (Reference Adams2020) recounts that during his time in the behavioural insight team at the Financial Conduct Authority in the UK they were likely to go along with the public body's constraints, for example by implementing mainly low-risk nudges: ‘At the start of the seven year period, we would say, that's fine, let's just do it anyway to get the experience and to try something out. But we sort of realised actually this was not a sensible way to do things. So our approach changed a little bit over time. I think early on we were happy to be more flexible.’ Another interviewee of a behavioural insights unit, who wants this quote to be used anonymously, adds: ‘Obviously we cherish our autonomy. But I also know I might have to collaborate with this person again sometime.’

Academic researchers, on the other hand, seem to experience more freedom when it comes to setting the terms and conditions of the research project. Dan Ariely (Reference Ariely2019), founding member of the Center for Advanced Hindsight, says: ‘For me, experiments with public partners do not mean a step back in scientific rigor. Because I am also happy to say no to an experiment. It's helpful that we are an outside company.’ A similar view is put forward by Dina Pomeranz (Reference Pomeranz2020) from Zurich University: ‘Basically, for quantitative research we need a certain number of observations. If they don't have that, we cannot do the study.’ Also for Johannes Haushofer (Reference Haushofer2021) from Stockholm University, there are non-negotiables: ‘If someone's not willing to randomize, mostly that's the end of the conversation for me.’

For behavioural insight teams like the BIT, it is more about explaining the statistical needs in plain language and gathering understanding: ‘It's being very clear upfront about what standards you have and why. It's good to explain very carefully and be prepared to have these conversations several times. You will have to tell different people. Explain concepts you have. Power calculations is not something that's intuitive to many people but it's finding a way to making it intuitive’, Alex Sutherland (Reference Sutherland2020) summarizes.

When the interviewees were explicitly asked whether they were free to walk away from an experiment in case of quality concerns, one interviewee admitted: ‘Walking away from an entire project is difficult. There are contractual obligations. I mean, there are implications, not for me personally, but for the project itself.’ Another one added: ‘We could not walk away at any time, no. Once we've invested the political capital and the energy of our partner, walking away from a trial is probably not going to go down very well. That's why we were always very careful in our negotiations and be very clear that there is a contracting process, and there's always a stop-go-decision at the very end.’

Behavioural insight team members also seem to be more willing to adjust to the time constraints set by the public partner. ‘One difference to academia is the timelines we are working on can often be very different. We might be trying to turn around a trial in a number of days or weeks rather than months or years’, Alex Sutherland (Reference Sutherland2020) from the BIT describes.

Wilte Zijlstra (Reference Zijlstra2020) from the behavioural insight team of the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets, even sees himself as an advocate of his organization's interests: ‘When it gets too academic, I tell my colleagues at the behavioural insight team: Don't forget about the practical aspects. Think about what is relevant for supervision.’ Jaap Drooglever (Reference Drooglever2021) from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Kingdom Relations adds: ‘Most of the municipalities are really far from thinking in the way the behavioural insight team does. These are two different worlds of thinking. But it can be addressed: by a lot of dialogue.’

Quite fittingly many interviewees mentioned that communicating research results in a way that makes it accessible to a non-scientific audience is a core skill of a behavioural insight team. ‘It's knowing where to put the information you are producing. We definitely don't prioritize publishing journal articles but we do prioritize to make sure that whatever is produced is accessible to people who are not specialists, who are not researchers, and we make it as easy as possible for them to understand the implications of results that we find’, Alex Sutherland (Reference Sutherland2020) says. It is hence not surprising that three out of six interviewees working on behavioural insights within a public body held positions as communications professionals in their organisation before (Maser, Tangen, Zijlstra).

From a positive perspective, Ruth Persian (Reference Persian2020) from the BIT points out: ‘The advantage of being external is having a fresh pair of eyes. We can suggest things and get away with them, where civil servants might be a bit more hesitant because they will still be around at the end of the project.’ Yet she also is very aware of certain constraints: ‘We are a consultancy. So ultimately, if the government partner refuses or feels very uncomfortable with a certain design, then we might have to adapt our approach.’

A systematically different research agenda of cooperative research could arise from that. As Delaney (Reference Delaney2018) sketches out in his recent article on the BIT: ‘There is a danger that behavioural insights trials will accumulate a large amount of local information on projects specifically selected for their suitability for treatment and with outcomes determined by local agency pressure.’ This study provides some first explorative evidence to support this apprehension.

Risk aversion of public bodies

As the most important reason for the pressure on adjusting scientific standards, the qualitative interviews identified a high degree of risk aversion in the public body, while the quantitative data on this aspect is not as clear cut. When respondents were asked how often they had the impression that their research opportunities were limited by a high degree of risk aversion in their public partner in comparison to experiments with other partners, only a slight majority experienced this more frequent or always (see Table 4). However, the answering pattern might have been influenced by the formulation of the question which did not ask for the absolute frequency in which respondents experienced high risk aversion but for a comparison to experiments with other partners. If some respondents had only conducted experiments with public partners before and did not feel represented by the two answering options which incorporated that fact (namely: never and always), they would very likely be inclined to pick the answering option equally frequent since they have no comparison.

However, interestingly, again a difference in answering patterns of academic researchers and public employees can be observed. Even though subsample sizes are small, it is remarkable that the greatest share of public employees indicate that they always experienced high risk aversion. In contrast, not a single academic researcher chose that option. This might be due to the fact that, as discussed above, researchers feel free to walk away from a cooperation if their required standards are not met.

Notably, during the qualitative interviews, the topic of risk aversion in the public body was frequently raised. ‘Public servants can lose a lot and do not have much to win. They can win for the country but not for themselves. They need to step out of their comfort zone a big way’, Dan Ariely (Reference Ariely2019) from Duke University says. Dina Pomeranz (Reference Pomeranz2020) from Zurich University shows understanding for constraints resulting from that: ‘Responsible leaders of course have to be risk averse to some degree. If the payoff is small and it's not worth taking any risks for it, they are unlikely to agree to a collaboration. If knowing the answer to the research question is of value to them, they tend to be more willing to take the risk.’ Alex Sutherland (Reference Sutherland2020) from the BIT adds: ‘It's the fear of the unknown. If people have done other kinds of evaluations like quasi-experimental designs, they may be familiar with those kinds of things. But changing something that's been done and planned, going against the status quo, that's more difficult. The process of change might feel alien to them.’

Experiments might also bring about unwanted evidence. ‘Science is kind of risky. You don't know what the answer is going to be. When you experiment, it might result in something that is contrary to what I would like it to be’, Wilte Zijlstra (Reference Zijlstra2020) from the Authority for the Financial Markets summarizes his colleagues’ reservations. Alex Sutherland (Reference Sutherland2020) from the BIT consents: ‘It requires a great deal of faith from the delivery partner knowing that the end result of the evaluation could be that their intervention was not successful in improving outcomes. It's really hard if they have to sell that it hasn't really worked or – as worst outcome – that it made things worse.’ A similar view is put forward by Johannes Haushofer (Reference Haushofer2021) from Stockholm University: ‘For public servants, it takes a lot of courage to run a study. Because trials can produce bad results for your program, it can fall apart, and then you've spent a lot of money and nothing to show for it. It's a risky proposition. And so if you do it with partners that you know and trust, that can make it easier.’

Researchers looking for collaboration can actively address this fear: ‘One aspect that they highlighted about why they accepted this proposal as opposed to some other ones is that it had a lot of safeguards about how we would avoid unintended outcomes. The proposal was careful to protect their institution from potential problems’, Dina Pomeranz (Reference Pomeranz2020) recounts her very first collaborative experiment with a public partner. Another way out of this is ‘building trust and reputation’, Dan Ariely (Reference Ariely2019) from Duke University emphasizes. ‘Even with being well known as a researcher, I do so much free advice and trust building. Normally, I give an introduction into behavioural economics, describe a small problem I am working on and sketch out a project that will come in 20 years. I call it lubricating the trust machine.’

Yet the public partner does not only need to build trust into the researcher but also into the intervention. For this, best practice examples from the public sector help, Lindsey Maser (Reference Maser2020) from the City of Portland emphasizes: ‘Since behavioural science and running RCTs is still fairly new in US government, and government tends to be very risk-averse, it's incredibly helpful to have examples of successful applications from other governments. It's easier to get approval to try something another government had success with than to try something that's never been done and might fail.’ Paul Adams (Reference Adams2020), formerly at the behavioural insights unit of the UK financial regulator, confirms: ‘You can then rely on external expertise to back your approach.’ A view that is also shared by Jaap Drooglever (Reference Drooglever2021) from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Kingdom Relations in the Netherlands: ‘Experiments give more arguments for the internal process to say: OK, we have to do it another way because the result from this experiment is that we have to redesign something.’

A decisive role in the process plays the media, several interviewees emphasized (Ariely, Reference Ariely2019; Maser, Reference Maser2020; Pomeranz, Reference Pomeranz2020; Tangen, Reference Tangen2020; Zijlstra, Reference Zijlstra2020; Aki, Reference Aki2021). ‘As soon as anything gets out, you then tend to get a lot of questions and that creates a lot of work and essentially media requests. And so organisations in the public sector are generally relatively risk averse in terms of putting things up publicly’, one interviewee describes. Thomas Tangen (Reference Tangen2020) from the Norwegian Tax Authority personally had to deal with bad publicity after cooperating with academic researchers on a tax trial (published by Bott et al. (Reference Bott, Cappelen, Sørensen and Tungodden2019)): ‘It actually became a media issue afterwards. Because some lawyers argued that we treated people differently. Some taxpayers were told “We know you have some money abroad” and others were told “You should just declare everything”, we did not say what we knew. That was a big discussion afterwards.’ Even though the Director General publicly defended the experiment and no legal issue followed, attitudes within the administration changed: ‘The notion was that we have to be very cautious, because at the end of the day we are dependent on people's trust. We still are doing experiments but we have to have that discussion every time’ (Tangen, Reference Tangen2020).

Transparency and quality control in collaborative experiments

Given the documented pre-selection of topics under investigation in collaborative research and the apparent pressures on research partners involved, it seems more important than ever for evidence-based policy advice that high quality evidence provides the groundwork to back up recommendations (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2014; Pomeranz, Reference Pomeranz2017; Smets, Reference Smets2020). Yet, as third main finding, this study documents that transparency and quality control in collaborative research tends to be low as manifested in the application of pre-registry, publication of results, and the comparison of short- and long-term effects.

Pre-registry

In the scientific community, publishing a pre-analysis plan for experimental research has become a highly recommended means of quality control (World Bank, 2020).Footnote 16 Yet in collaborative experiments with a public partner, it does not seem to be commonly used. In the anonymous survey, almost 45% of study respondents indicate that they have never pre-registered any of their collaborative experiments before (see Table 5). Another 14% did this less frequently than with other partners. For 18 of the 21 respondents, who chose either one of these two answers, the affiliation is known. The vast majority of them are public employees who have been shown to yield a great influence on the study design of cooperative experiments. It hence seems that another distinct feature of cooperative experiments is a tendency to not pre-register.Footnote 17 Interestingly, however, the small minority of respondents who states to always pre-register are not the academic researchers: none of them indicates to have done so in contrast to two public employees.

Table 5. Frequency of pre-registering

Notes: Respondents were asked how frequently they pre-registered their experiments with public partners compared to experiments with other partners. For public servants, the question in the online survey was slightly modified, namely: ‘How frequently did you register a pre-analysis plan for your experiments (e.g., in the AER RCT registry)?’ The answering options were: never, in the minority of cases, 50% of the time, in the majority of cases, always. All three public servants picked never and are hence listed in this table in the corresponding category. The full sample also comprises of those respondents who did not indicate their affiliation. Values may sum up to less or more than 100% due to rounding. Of the 70 survey participants, only those with own experiences in collaborative research were asked these questions. Absolute numbers in brackets.

a The answering options ‘never’ and ‘always’ include the statement that the respondent only conducted experiments with public partners.

When comparing the answering options less frequent, equally frequent and more frequent, most respondents indicate that they pre-register cooperative experiments equally frequent (36%) or less frequent (14%) than experiments with other partners. None of them indicates that this was more frequent the case (0%). For those answering options, all answers can be accounted for by affiliation. The analysis shows that researchers and public employees contribute to the results in the same absolute numbers. It has to be noted, however, that among public employees almost exclusively members from behavioural insight teams are present, since for public servants these answering options were not available in the online survey.

Several qualitative interviews confirmed the tendency to not upload a pre-analysis plan for cooperative experiments. According to the interviewees, three main hurdles prevent from pre-registering their experiments at established platforms: time pressure, confidentiality issues and the aim of keeping experimental subjects and the media uninformed that a trial is underway (Adams, Reference Adams2020; Persian, Reference Persian2020; Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2020; Tangen, Reference Tangen2020; Zijlstra, Reference Zijlstra2020; Aki, Reference Aki2021; Drooglever, Reference Drooglever2021). Wilte Zijlstra (Reference Zijlstra2020) from the behavioural insight team at the Dutch Authority for Financial Conduct weighs the pros and cons: ‘Setting up a pre-analysis plan helps you with your design. But, again, it costs time. And you are operating under a deadline.’ ‘We use our advisory board for the function of a pre-analysis check. We will consult them about the way we have designed experiments and whether they approve of it or not’, Jaap Drooglever (Reference Drooglever2021) from the Dutch Ministry of Internal Affairs and Kingdom Relations describes. Yet, he also clarifies that they would not make anything public before the experiment starts: ‘I don't think we will upload a pre-analysis plan publicly because I don't know how who will react. But there are no real barriers to do so.’

For the work of the BIT, Ruth Persian (Reference Persian2020) explains: ‘We do have research protocols for every single experiment that we run, but usually we do not pre-register publicly. Often this is because of confidentiality issues with our partners. Social science registries are also quite a new development – but the importance of pre-registration is definitely something we are conscious of and are thinking about.’ Persian also thinks that more pre-analysis plans will be openly published in future: ‘To be honest, I think it's partly a resource problem that we don't do that by default. If we come up with a process, it's probably not that much work.’

Publication of results

Yet it is not only lacking pre-registration that gives rise to concerns with regard to research transparency. According to the interviewees, a substantial number of trials with public partners does not even get published after completion. This finding is in line with the results of a recent meta-study by DellaVigna and Linos (Reference DellaVigna and Linos2020). They document that as much as 90% of the trials conducted by the two largest Nudge Units in the United States have not been published to date, neither as working paper nor in any other academic publication format. According to Sanders et al. (Reference Sanders, Snijders and Hallsworth2018), two problems follow from this: (i) trials that are not published at all produce a public file drawer problem, especially when null and negative results are selectively held back, and (ii) trials that are published with insufficient details regarding their methodology prevent any quality control since the reliability of their results cannot be assessed appropriately.

‘We want to push for greater transparency in our work. We engage with people on this point quite frequently. Yet being a commercial research organization, the incentives are not towards publishing. The incentives are to get the job done’, Alex Sutherland (Reference Sutherland2020) from the BIT describes the tradeoff. Ruth Persian (Reference Persian2020) also puts attention to personal factors: ‘That's all great if you actually get something out of the publication. And our publication on my CV is of course great. But it was also a lot of work that has to happen next to our day job.’ Helen Aki (Reference Aki2021), too, describes that she has to prioritize tasks given her limited time resources: ‘We don't publish all the trials we conduct. And the honest reason is the time it takes to really write a report that is suitable for a public audience and get through the approval processes and everything else. Ultimately we're a government organisation and we're here to make change for New Zealanders. And so it's hard to make the time to do the kind of work for publishing.’ Wilte Zijlstra (Reference Zijlstra2020) from the behavioural insight team at the Dutch Authority for Financial Conduct made similar experiences: ‘If you want to publish externally, you think about: how will this be interpreted and understood? So it's a cost-benefit assessment: how much extra time would it cost to get an external publication and is it worth the time? For reports internally, people know the context, you don't have to explain everything.’ He also sees the risk that some firms would use null or negative results for legal complaints against the regulator: ‘When you get court cases, they can use published reports against us. They would quote us: “you're saying we should do this. But you're also saying it doesn't work”.’

Jaap Drooglever (Reference Drooglever2021) from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Kingdom Relations has quite the opposite impression. He perceives tight boundaries around the possibilities of holding results back from being made public: ‘To keep certain information as classified, you need really good arguments, based on law. And I can't really see such arguments for this pilot, on the contrary: We want to share this way of working, and our results. So other than the privacy aspect of a pilot, there are no real barriers to be as transparent as we can.’

In the academic literature, publication bias is a well-known phenomenon: If researchers have a greater tendency to submit, and editors a greater tendency to publish studies with significant results, the publicly available evidence will be systematically skewed (Franco et al., Reference Franco, Malhotra and Simonovits2014). That's why researchers strongly advocate to clearly codify an agreement like a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the cooperation partner beforehand that all findings can be shared publicly (Karlan & Appel, Reference Karlan and Appel2018; Pomeranz & Vila-Belda, Reference Pomeranz and Vila-Belda2019).

It is hence not surprising that for academic researchers like Dina Pomeranz (Reference Pomeranz2020) from Zurich University publishing the results of an experiment is a non-negotiable prerequisite for any cooperation: ‘It is important to always set clear terms ex ante of what can get published, for example general results can be published, but no individual data. For scientific integrity it is important that the institution does not have a veto power at the end if the results are not what they hoped for.’ Christian Gillitzer (Reference Gillitzer2020) from Sydney University, too, did not experience any constraints with respect to publication, just different priorities of the public partner: ‘They're not primarily interested in making contributions to academic literature. Once the initial report was written with the findings, there was a conference call, and after that they briefed their senior people and then considered essentially the case closed. We contacted them with some follow up questions during the revision process to the paper, and they were receptive and helpful and wished us well. But they had gotten out of what they wanted to do and had moved on.’ From the public partner's perspective, the disengagement might be efficient and rational (Karlan & Appel, Reference Karlan and Appel2018). Yet in sum it contributes to a situation where the publication of results from collaborative experiments is not considered the default and hence another essential requirement for high-quality evidence informing policy decisions is not met.

Short- and long-term effects

A third aspect of quality control is to check whether effects are sustainable over time by comparing short-term to medium- or long-term effects. In collaborative research with public partners, this means, too, does not seem to be commonly used. Quite the contrary: the vast majority of study respondents (73%) indicate that the maximum time of observation to measure a (long-term) effect in any of their collaborative experiments was 12 months (see Table 6). Only 9% measured an effect after more than 24 months. Even though these results do not provide evidence that the period of observation in cooperative studies is shorter than in other research, it does show that in the field of cooperative research another criterion expected from high quality evidence is not satisfied.

Table 6. Maximum period of observation

Notes: Values may sum up to less or more than 100% due to rounding. Of the 70 survey participants, only those with own experiences in collaborative research were asked these questions. Absolute numbers in brackets.

However, as the qualitative interviews point out, time might bring about some improvements. According to Dan Ariely (Reference Ariely2019) from Duke University, the concentration on short-term effects could be a phenomenon mirroring the relative young age of testing behavioural interventions with a public partner: ‘We started with low-hanging fruits to show success. There was a focus on short-term effects. Now the field will develop into longer term experiments.’ Yet long-term studies also need a public partner to go along. While some researchers mention that policy makers find long run effects of great importance (Czibor et al., Reference Czibor, Jimenez-Gomez and List2019), others document exactly the opposite (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Snijders and Hallsworth2018). This study contributes to the latter view by finding a high institutional impatience when it comes to the time span of research projects. Whether policy makers will truly provide enough administrative resources to measure long-term effects, remains an open question.