Introduction

Thrust into the spotlight in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, behavioral public policy (BPP) interventions to reduce and contain the virus covered widespread territory, ranging from an initial focus on information dissemination, to norming effective handwashing, encouraging social distancing and mask-wearing, and promoting shelter-in-place recommendations (Bavel et al., Reference Bavel, Baicker, Boggio, Capraro, Cichocka, Cikara, Crockett, Crum, Douglas, Druckman, Drury, Dube, Ellemers, Finkel, Fowler, Gelfand, Han, Haslam, Jetten and Willer2020; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Dawes, Fowler and Smirnov2020; Lunn et al., Reference Lunn, Belton, Lavin, McGowan, Timmons and Robertson2020). As a field explicitly charged with applying evidence-based behavioral insights to inform effective public policy (Galizzi, Reference Galizzi2014: Hansen, Reference Hansen2018), BPP was, arguably, perfectly positioned to deliver the goods. Yet, despite its clear urgency and applicability to the pandemic (Manning et al., Reference Manning, Dalton, Zeina, Vakox and Naru2020), BPP interventions have fallen somewhat short of expectations, and even individually effective interventions have struggled to contain the force of the coronavirus' spread to any substantive degree.

The extreme and varied conditions that shaped behavioral responses to the pandemic – prolonged and persistent uncertainty, waves of often contradictory approaches (Nelson & Witko, Reference Nelson and Witko2020), and a high level of global variability that hampered generalizability (Iwuoha & Aniche, Reference Iwuoha and Aniche2020; Nicola et al., Reference Nicola, Sohrabi, Mathew, Kerwan, Al-Jabir, Griffin, Agha and Agha2020) – reinforce that behavioral design cannot, and should not, be expected to manage such challenges on its own (Thaler, Reference Thaler2016). In the USA, for example, efforts to bolster public health recommendations about wearing masks were stymied by system-level supply issues, in addition to the entrenched effects of personal autonomy and political identity that fed reactance against nudges and appeals to social norms. More globally, even effective shelter-in-place mandates to reduce viral proliferation have also contributed to second-order effects such as struggles with behavioral health (Barari et al., Reference Barari, Caria, Davola, Falco, Fetzer, Fiorin, Hensel, Ivchenko, Jachimowicz, King, Kraft-Todd, Ledda, MacLennan, Mutoi, Pagani, Reutskaja and Slepoi2020).

However, we suspect that some of the limitations, or ‘brittleness,’ exhibited by behavioral responses to Covid-19 may be the direct result of using methodology that is ill-suited to address challenges with this level of ongoing complexity. Traditional BPP methodology tends to focus on addressing bounded, present-tense and discretely measurable behavioral change, combining findings from empirical experiments with knowledge about the target environment to inform policy that achieves immediate relevance and results (Hallsworth et al., Reference Hallsworth, Snijders, Burd, Prestt, Judah, Huf and Halpern2016; Cash et al., Reference Cash, Hartlev and Durazo2017; Irrational Labs, 2020). Optimizing for targeted solutions has emphasized the use of evidence-based problem-solving and randomized control trials (RCTs) to evaluate the efficacy of interventions; the same urge has more recently fed enthusiasm for advanced data analytics and its ability to heighten customization to increase the precision and efficacy of interventions (Kelders et al., Reference Kelders, Kok, Ossebaard and Gemert-Pijnen2012; Mills, Reference Mills2020). In both cases, quantitative demonstration of scientific rigor has undeniably contributed to the field's achievements and perceived credibility (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Snijders and Hallsworth2018).

But the same attributes that contribute to BPP's success when creating policy interventions for ‘last-mile’ challenges have also positioned it as a largely tactical discipline that prioritizes accurately solving for narrow challenges over addressing underlying conditions or systemic root causes and short-term outcomes over greater resilience and long-term impact (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Loewenstein, Jankovic and Ubel2009; Reijula et al., Reference Reijula, Kuorikoski, Ehrig, Katsikopoulos and Sunder2018; Ewert & Loer, Reference Ewert and Loer2020). Not only does this emphasis on tactical problem-solving artificially constrain the nature of challenges the field might address, but it can reinforce tendencies to create solutions for individual issues within systems that may themselves be flawed or inequitable. It also puts current methodological approaches at odds with critiques from a growing number of behavioral practitioners who increasingly suggest that the field must find ways to tackle more complex and upstream challenges if it is to achieve its full promise and impact (Hansen, Reference Hansen2018; Spencer, Reference Spencer2018).

Resolving this tension puts the field at something of a crossroads. In one direction lies BPP's current trajectory of crafting finely tuned solutions for a narrow set of well-defined problems, and in the other applying current methodologies to more diverse challenges that puts them at increased potential risk for interventional brittleness. However, lessons learned from the mixed success of behavioral interventions to Covid-19 suggest that addressing interventional brittleness may not be an issue of simply applying traditional methodology better within complex or dynamic contexts and social systems (Holling, Reference Holling2001; Tromp et al., Reference Tromp, Hekkert and Verbeek2011; Michie et al., Reference Michie, Richardson, Johnston, Abraham, Francis, Hardeman, Eccles, Cane and Wood2013), but rather adopting an expanded set of methodological practices better suited to complexity.

This presents yet a third option: to define a more strategic model of problem-solving to combat the inherent brittleness that results from current problem-solving methodologies. Below, we outline the imperative for BPP practitioners and researchers to take this third path, both in the interest of applying these insights in complex contexts and as a means to expand BPP research and research partnerships. First, we discuss how current BPP methodological approaches contribute to contextual, systemic, and anticipatory forms of brittleness, which hinder the greater efficacy of behavioral change programs. Second, we articulate how taking a more proactive, strategic approach – strategic behavioral public policy (SBPP) – expands on current methodology to imbue behavioral solutions with increased resilience to these forms of brittleness. Finally, we offer a road map for actionably applying SBPP, using the Covid-19 vaccine rollout as a sample case, and conclude with a discussion of potential considerations and path forward.

Types of brittleness: contextual, systemic, and anticipatory

BPP's preference for tightly framed problems, evidence-based interventions, and rigorous evaluative tools contribute significant benefits both to developing effective solutions and to communicating their credibility. Well-defined, discrete problems are an excellent fit for empirical inquiry. ‘Gold standard’ RCTs allow practitioners to more confidently quantify and attribute behavioral change to interventions, increasing BPP's methodological legitimacy to disciplines that sit outside the behavioral sciences (e.g., economics) in the form of translational boundary objects (Star & Griesemer, Reference Star and Griesemer1989).

These norms are not in and of themselves bad or misguided. However, this steady diet of unambiguously defined problems and analytic methodology has, to some degree, made BPP a victim of its own success. The same precise and targeted interventions that provide confidence in ‘fit’ also contribute to the challenge of generalizability. While behavioral findings may be empirically sound, the experiments from which they are derived typically do not reflect real-world complexity and uncertainty: real-world conditions present heterogeneous and nondeterministic effects that can disrupt interventions' original intent if not supplemented by additional personal and cultural insight (IJzerman et al., Reference IJzerman, Lewis, Przybylski, Weinstein, DeBruine, Ritchie, Vazire, Forscher, Morey, Ivory and Anvari2020). The effects of solutions, once implemented, may be simultaneously boosted and dampened by other ancillary forces occurring within complex adaptive systems, characterized by nonlinear, multilevel behavior due to a lack of central control. Finally, even successful interventions may function within larger systems that are themselves inequitable and risk perpetuating or amplifying these inequities.

Collectively, this suggests that BPP's methodological attributes may inadvertently contribute to three forms of brittleness (see Table 1) in behavioral interventions: contextual brittleness, due to an insufficient grasp of the different perspectives and interpretations of proposed policy interventions; systemic brittleness, the failure to address how system forces both within and outside the intervention's sphere may impact their effectiveness; and anticipatory brittleness, which ignores how external conditions and end recipients of policy may themselves evolve.

Table 1. Behavioral brittleness: contextual, systemic, and anticipatory.

Contextual brittleness

BPP methodology can result in contextually brittle solutions when interventions are insufficiently situated within the particulars of their context or are conceived with the assumption of ‘normal’ or universal values that ignore the pluralistic and heterogeneous nature of values, contexts, resources, or perceptions (Anderson, Reference Anderson1993; Soman & Hossain, Reference Soman and Hossain2020). This can occur, for example, when insights from the behavioral literature are applied reductively to real-world user contexts (e.g., findings on increasing gym attendance are assumed to be a proxy for achieving good health) or when variable contexts lead individuals to embrace different behaviors or preferred outcomes due to cultural differences. As such, solving for contextual brittleness bears a family resemblance to solving for generalizability: where efforts to achieve generalizability typically focus on translating solutions that worked in one context [X] into another [Y], contextual brittleness occurs when a solution that is presumed to apply equally or generally across a single setting or situation [X] does not sufficiently take into account the multiplicity of perspectives that cause interventions to effectively splinter into a more diverse set of contexts [X1, X2, and X3].

Several examples of contextual brittleness are evident, in the case of Covid-19, in incorrect assumptions of universal access to fresh water and soap required for handwashing (Iwuoha & Aniche, Reference Iwuoha and Aniche2020; World Health Organization, 2020) and in American Black men's concerns during the pandemic's early stages that wearing masks would result in tradeoffs between one form of safety (public health) and another (fears of racial profiling) (Alfonso, Reference Alfonso2020; Vargas & Sanchez, Reference Vargas and Sanchez2020; Yancy, Reference Yancy2020). In both cases, ostensibly benign or straightforward interventions were not actually neutral, and instead indicative that policy designers' assumptions of universal norms or shared values need to be interrogated during solution development (Djulbegovic & Guyatt, Reference Djulbegovic and Guyatt2017).

Systemic brittleness

A second form of vulnerability – systemic brittleness – can occur when solution development fails to consider critical system interactions, such as competing policies or trends, that cause interventions to function differently or in more limited ways than expected. For example, a nudge designed to encourage farmers to adopt water-saving practices in the water-scarce Colorado River Basin floundered when policy designers failed to consider the countereffects of competing policy interventions that incentivized ‘use-it-or-lose-it’ yearly water consumption rights (UCRC Staff & Wilson Water Group, 2018). As a result, a behavioral change intervention to address water scarcity that seemed sound at the scale of individual farmers ultimately had the opposite effect.

Even behavioral interventions that are successful in isolation may miss the mark if they fail to consider how spillover or system effects compound or influence solutions, such as automatic payment nudges that inadvertently offset other forms of debt reduction (Dolan & Galizzi, Reference Dolan and Galizzi2015; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Guttman-Kenney, Hayes, Hunt, Laibson and Stewart2018). Alternately, adopting expressed consent interventions in organ donation contexts as a means to overcome the limitations of presumed consent may still fail to consider other critical system factors, such as evidence that the presence of donor coordinators boosts organ donation and successful transplant rates over rates achieved with behavioral change alone (Sarlo et al., Reference Sarlo, Pereira, Surica, Almeida, Araújo, Figueiredo, Rocha and Vargas2016) or the uneven demand for particular organs (Wojda et al., Reference Wojda, Stawicki, Yandle, Bleil, Axelband, Wilde-Onia, Thomas, Cipolla, Hoff and Shultz2017). In each case, systemic brittleness can be reduced when practitioners take into account how other infrastructural forces and activities may bolster, dampen, or redirect an intervention's intended effects.

It is worth noting that interventions can suffer simultaneously from multiple, compounding forms of brittleness. In the case of Covid-19, for example, entreaties to wear masks have struggled to overcome the perceived denial of personal liberties or conflation of mask-wearing with political beliefs (Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2020a) – a manifestation of potential contextual brittleness – while conflicts between national-scale public health recommendations from the US Center for Disease Control (CDC) that contradicted local-scale directives coming from individual businesses or municipal officials (Nelson & Witko, Reference Nelson and Witko2020) indicated the potential for systemic brittleness.

Anticipatory brittleness

Change is inevitable, but proactively designing for a third limitation – anticipatory brittleness – recognizes that interventions may weaken in the face of shifting or newly emergent contexts, and that certain trajectories, shifts, and cyclical events can be at least partially foreseen. Identifying regularly occurring cycles or upcoming events can help BPP practitioners consider emergent circumstances before they arise, such as when violations of social distancing and mask-wearing predictably increased with the emergence of warmer weather or when year-end holiday activities resulted in new peaks of infection. While many instances of anticipatory brittleness may arise from acute shifts in conditions, even well-established interventions like Save More for Tomorrow™ (Thaler & Benartzi, Reference Thaler and Benartzi2004) may become increasingly brittle over time as the cohort of gig economy workers continues to grow and employer-run 401 ks become less the norm (Yildirmaz et al., Reference Yildirmaz, Goldar and Klein2020).

Anticipatory brittleness can also occur when policy interventions are installed without the recognition of unintended consequences or potential second-order implications of policy – as in perverse ‘cobra effect’ outcomes, in which policy interventions inadvertently spur behaviors contrary to their initial intent (Siebert, Reference Siebert2001) – or when individuals progressively adapt to interventions over time. In the case of Covid-19, anticipatory brittleness occurred when initial recommendations from international health organizations, including the US CDC and World Health Organization (WHO), asserted that laypeople without symptoms would not benefit from wearing masks in part to reserve N-95 masks for healthcare workers who urgently needed them; subsequent messaging fed by an evolving understanding of viral transmission that masks provided essential protection for everyone, regardless of disease status, led to hoarding, confusion, and skepticism that undercut its effectiveness (CDC, 2020; Missoni et al., Reference Missoni, Armocida and Formenti2020).

While some effects of anticipatory brittleness may occur and resolve on a short timeframe, others are likely to have long-term consequences. The suggested mandate to work from home has already contributed to second-order effects on mental health (Barari et al., Reference Barari, Caria, Davola, Falco, Fetzer, Fiorin, Hensel, Ivchenko, Jachimowicz, King, Kraft-Todd, Ledda, MacLennan, Mutoi, Pagani, Reutskaja and Slepoi2020), reported increases in domestic violence (Bradbury-Jones & Isham, Reference Bradbury-Jones and Isham2020), and real estate trends (Gujral et al., Reference Gujral, Palter, Sanghvi and Vickery2020; Tanrıvermiş, Reference Tanrıvermiş2020), in addition to its obvious effect on daily household and professional activities. However, these shifts are already proving to have a disproportionately negative effect on women's employment and productivity, threatening to further exacerbate existing hiring, promotion, and income disparities in the longer term (Vincent-Lamarre et al., Reference Vincent-Lamarre, Sugimoto and Larivière2020). Similarly, findings that remote learning is disproportionally causing minoritized and underserved students to fall behind in school also suggest that public health responses to the pandemic may amplify existing inequities that range far beyond a single lost year of school (Alliance for Excellent Education, 2020; Hampton et al., Reference Hampton, Fernandez, Robertson and Bauer2020).

Methodological implications to strategically addressing interventional brittleness

Many have already recognized BPP's disciplinary limitations, calling attention to cultural and contextual factors in design and implementation (Levinson & Peng, Reference Levinson and Peng2006; Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Chatterjee, Mishra and Mishra2019; Soman & Hossain, Reference Soman and Hossain2020), the need for a systems approach (Blizzard & Klotz, Reference Blizzard and Klotz2012; Mažar, Reference Mažar2019; Ewert & Loer, Reference Ewert and Loer2020), and solutions that adjust to users' emergent needs and behaviors (Broekhuizen et al., Reference Broekhuizen, Kroeze, van Poppel, Oenema and Brug2012; Riley et al., Reference Riley, Nilsen, Manolio, Masys and Lauer2015). Even so, for the most part, these approaches still assume the use of traditional problem-solving methodologies and past data as evidence for future states (Howlett, Reference Howlett2020; Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2020b), putting them at risk for falling back on old assumptions about what is worth measuring or prioritizing available data over what is most relevant.

While this may work as intended when navigating simpler contexts, more complex challenges and ‘wicked problems’ like the Covid-19 pandemic tend to resist analytic methodologies or adherence to past logic and trajectories (Rittel & Webber, Reference Rittel and Webber1973; Buchanan, Reference Buchanan1992). Navigating these more ambitious and ambiguous challenges may, therefore, require cultivating a greater appreciation for speculative and generative problem-solving modes (getting the right idea) as a co-equal complement to analytic and evaluative ones (getting the idea right) (Saltelli et al., Reference Saltelli, Bammer, Bruno, Charters, Fiore, Didier, Espeland, Kay, Piano, Mayo, Pielke, Portaluri, Porter, Puy, Rafols, Ravetz, Reinert, Sarewitz, Stark and Vineis2020). Employing this more proactive, abductive approach complements BPP's familiar ‘evidence of’ – proof of what works – with ‘evidence for’ – testimony for what could be – to generate hypotheses and solution components that integrate less obvious, but still plausible, scenarios into problem framing and policy intervention design (Biesta, Reference Biesta2007; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2020; Hermus et al., Reference Hermus, van Buuren and Bekkers2020). Addressing brittleness in these situations may, therefore, lie in an increased willingness to be strategically ‘vaguely right rather than exactly wrong’ (Read, Reference Read1920).

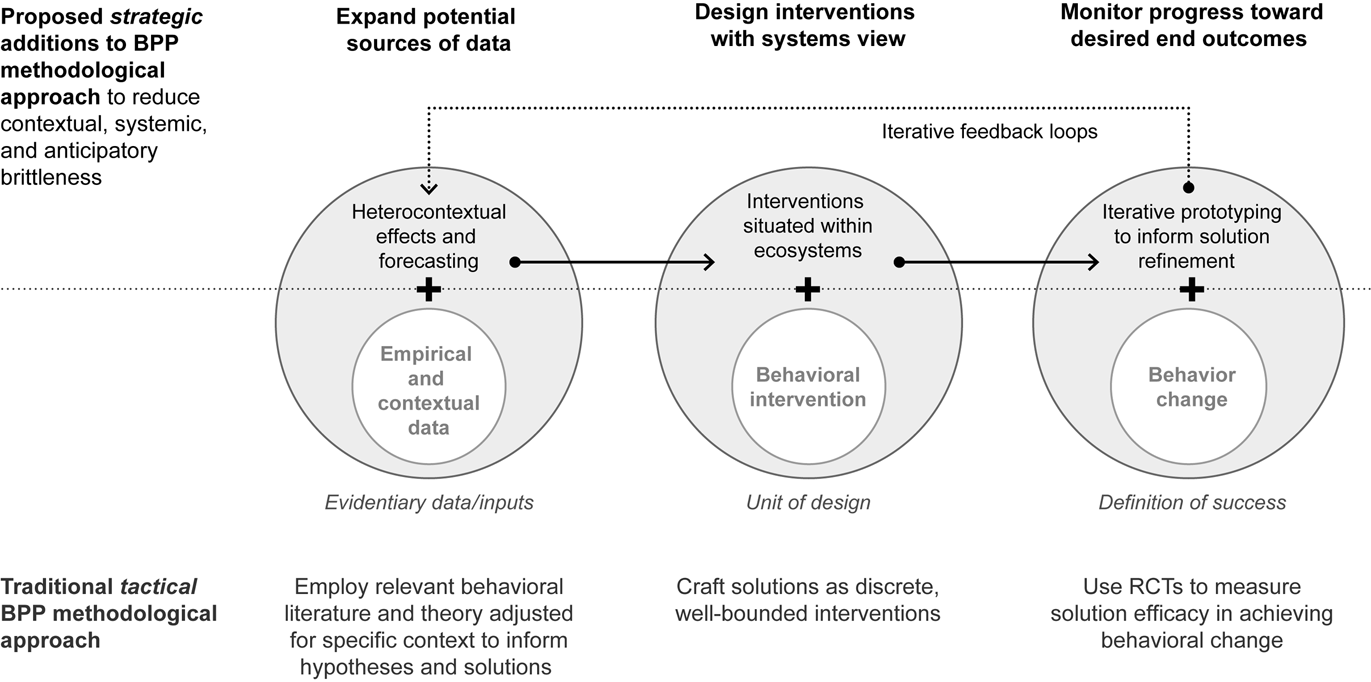

The notion of strategy is not altogether new to BPP discourse, and, in fact, a working definition of behavioral economics as ‘psychology meets market forces’ (Thaler, Reference Thaler2016) is highly aligned with a strategic mindset and operative context. Although ‘strategy’ has historically referred to helping policymakers make more strategic decisions rather than encouraging the discipline itself to become more strategic (Bryson, Reference Bryson1988; Dudley & Xie, Reference Dudley and Xie2020; George, Reference George2020), public administrators have more recently adopted it to describe the creation of public value rather than domination over competitors (Bryson & George, Reference Bryson and George2020). In practice, SBPP's underlying problem-solving path remains essentially the same as that of BPP, supplementing informational, evaluative, and analytic problem-solving methods with inspirational, generative, and synthetic approaches (Cross, Reference Cross2006; Bjögvinsson et al., Reference Bjögvinsson, Ehn and Hillgren2012; van Buuren et al., Reference van Buuren, Lewis, Guy Peters and Voorberg2020). Applying a more strategic lens at each step, however, recenters behavioral challenges as part of a larger sequence of judgments and actions (rather than discrete instances), situated in system contexts with an eye toward eventual end outcomes (not in isolation), which are both active and acted upon (because interventions themselves impact the conditions into which they are placed) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Strategic behavioral public policy methodology to combat brittleness.

Where before hypotheses are informed primarily by behavioral science literature searches and the immediate context (IJzerman et al., Reference IJzerman, Lewis, Przybylski, Weinstein, DeBruine, Ritchie, Vazire, Forscher, Morey, Ivory and Anvari2020), they now benefit from additional evidence that reflects the heterogeneous and emergent nature of implementation and user contexts. An expanded strategic view also provides a new insight into supporting and countervailing system forces that may impact interventions once they are implemented, highlighting the need to consider the role of ‘choice infrastructure’ as well as choice architecture. Finally, where behavioral change has historically functioned as the primary indicator of success, its more longitudinal contributions to intended outcomes are also monitored to indicate the potential need for course correction.

Expand potential sources of data

Given that contextual brittleness arises from a mismatch between decontextualized evidence and the specificity and complexity of real-world settings, even replicated findings with high internal validity are unlikely to achieve equivalent levels of external validity (Levitt & List, Reference Levitt and List2007; Camerer, Reference Camerer2011). Reducing potential brittleness in BPP, therefore, requires not only verifying the extent to which findings fit the context into which policy will be enacted (Diamond, Reference Diamond2010), but expanding the variety of data sources and use of mixed methods research, including qualitative, ethnographic, and phenomenological approaches, to supply a more well-rounded view of the relevant audience, challenge, and specific intervention context (Ewert & Loer, Reference Ewert and Loer2020).

However, gathering more data may not address brittleness if they serve only to reinforce or fine-tune incoming hypotheses about what good looks like. Despite the long-standing credo that behavioral economics should be used to nudge ‘for good’ and in users' best interests (Thaler & Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008; Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2018), in practice, this stance often presumes notions of good as defined by behavioral designers and policymakers, rather than by policy recipients. When norms and values are embedded into assumptions of what to solve for – or what the problem even is – practitioners can too easily overlook the potential for heterogeneous effects that put solutions at risk for contextual brittleness (Collins & Evans, Reference Collins and Evans2002).

In contrast, SBPP combats brittleness by taking a more pluralistic approach, eliciting a broader set of data about users and contexts to generate an understanding how heterogeneous populations may perceive or be unequally affected by interventions while hypotheses are still being formed (Grand, Reference Grand2020). For example, historically unequal treatment and access to healthcare has contributed to US Black and Brown populations' skepticism of public health officials, suggesting that Covid-19 vaccination messages delivered by trusted community leaders may prove more persuasive (Poteat et al., Reference Poteat, Millett, Nelson and Beyrer2020) than those delivered by medical professionals (Meng et al., Reference Meng, McLaughlin, Pariera and Murphy2016; Cotrau et al., Reference Cotrau, Hodosan, Vladu, Daina, Daina and Pantis2019; Golemon, Reference Golemon2019; Laurent-Simpson & Lo, Reference Laurent-Simpson and Lo2019) or government officials (Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson2013; Galizzi, Reference Galizzi2014). Although addressing contextual brittleness remains distinct from achieving generalizability, gaining heterogeneous insight across user contexts through generative research methodologies can also contribute to the development of abstracted principles, or decision rules, that indicate how desirable characteristics of solutions might apply elsewhere without resorting to formula (Bohlen et al., Reference Bohlen, Michie, de Bruin, Rothman, Kelly, Groarke, Carey, Hale and Johnston2020; Ho et al., Reference Ho, Leong and Yeung2020; Supplee & Kane, Reference Supplee and Kane2020). The use of these principles as guardrails for hypothesis development, thus, functions less as prescriptive mandates for solution development and more to provide a shared set of attributes across many comparable challenges, while also recognizing the need to address specific contextual conditions when implementing concrete policy interventions.

A second potential expansion of data to inform hypotheses is the strategic use of foresight. Designing for future states is already well established in behavioral science in the form of ‘planner-doer’ tensions (Thaler & Shefrin, Reference Thaler and Shefrin1981) or issues of control and volition (Nordgren et al., Reference Nordgren, Pligt and Harreveld2007; Sheeran & Webb, Reference Sheeran and Webb2016) such as when the stated desire to act sustainably contrasts with a lack of follow-through in the actual choice-making context (Johnson, Reference Johnson2019; Falco & Zaccagni, Reference Falco and Zaccagni2020). In addition, interest in superforecasters has indicated an openness to predictive data, albeit one primarily focused on improving individual judgment and decision-making ability rather than generating foresight into the systemic context into which interventions are to be applied (Mellers et al., Reference Mellers, Stone, Murray, Minster, Rohrbaugh, Bishop, Chen, Baker, Hou, Horowitz, Ungar and Tetlock2015). But as the pandemic has ably demonstrated, changing conditions that require solving for new challenges or that render interventions less effective – such as evidence showing that the anticipated near-term availability of a vaccine decreases social-distancing measures (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Campos-Mercade, Meier and Wengstrom2020) – demand more substantive future-facing methodology situated in replicable and scalable methods, rather than in individual expertise.

The use of sensing and strategic scenario planning to take a more longitudinal view on the implications of plausible future states or policy directions (Schoemaker, Reference Schoemaker1995; Amer et al., Reference Amer, Daim and Jetter2013), frequently used in strategic business decision-making, is less common in BPP. Still, its ability to contribute useful perspectives to inform behavioral strategy shows strong promise: for example, a series of pre-Covid-19 pandemic simulations conducted with senior international government officials raised now-familiar concerns, including the need to impose restrictions on travel, supply and demand issues, and challenges caused by conflicting state and federal directives (Maxmen & Tollefson, Reference Maxmen and Tollefson2020). While scenario planning is not infallible – the exercise also failed to anticipate the degree to which an uncoordinated federal response would hinder efforts to curtail the spread of the virus – scenario-based forecasting can combat brittleness by providing data on likely condition shifts, system effects, and user adaptation that might impact intervention success while solutions are still being developed, deployed, and refined.

Design interventions with systems view

The value of a systems view is common to many classic definitions of strategy, ranging from achieving impact within market environments and ecosystems (Ansoff, Reference Ansoff1979; Mintzberg, Reference Mintzberg1979; Henderson, Reference Henderson1989); references to patterns of actions and objectives (Learned et al., Reference Learned, Christensen, Andrews and Guth1969; Mintzberg & McHugh, Reference Mintzberg and McHugh1985); and a sense of striving for unified, comprehensive, and integrated plans that recognize, or even emphasize, the interconnections between multiple parts (Glueck, Reference Glueck1976; Uyterhoeven et al., Reference Uyterhoeven, Ackerman and Rosenblum1977). In a public policy context, complexity theory has afforded rich descriptions of public organizations as complex adaptive systems, indicating a need for adaptive stances among public policy practitioners when conceiving strategic approaches (Boulton et al., Reference Boulton, Allen and Bowman2015), designing for dynamic public values (Haynes, Reference Haynes2018), and developing public policy practices that focus on system resilience, patterns of practice, and adaptability. In parallel, complex system science methodologies have been widely applied by policy practitioners when designing programs for complexity (Hassmiller Lich et al., Reference Hassmiller Lich, Urban, Frerichs and Dave2017) and understanding critical policy issues such as climate change and mental health (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Waite, Dear, Capon and Murray2018), indicating an opportunity for increased BPP applications.

Still, traditional approaches to BPP targeting behavioral change have tended to place less emphasis on the ways in which interventions influence and are influenced by other components of a system or at multiple scales, or defining requirements for methodologies that deal with structural design and implementation within systems (Jilke et al., Reference Jilke, Olsen, Resh and Siddiki2019; Ewert et al., Reference Ewert, Loer and Thomann2020; Ewert & Loer, Reference Ewert and Loer2020). The lack of common behavioral models for analyzing external system forces analogous to those used in business strategy (e.g., PEST/PESTEL, STEEP, DPSIR, Lewin Force Field, etc.) suggests that designing for complex systems continues to present both a challenge and an opportunity for BPP (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Snijders and Hallsworth2018; Spencer, Reference Spencer2018), calling for a reconsideration of how to address policy system, institution, and implementation contexts with new tools, methods, and capabilities (Crowley et al., Reference Crowley, Stewart, Kay and Head2020).

Monitor progress toward desired end outcomes

Popular behavioral design wisdom tends to encourage solving for the narrowest unit of analysis, encouraging tactical focus on behavioral change and positioning problem framing at the level of outcomes as a common failure mode (Irrational Labs, 2020). Taken too far, however, ignoring how policy interventions feed end outcomes can inadvertently introduce brittleness by insufficiently considering how they function within a larger ecosystem unit level, and the extent to which individual policies contribute to larger strategic goals.

This focus on behavioral change as a unit of success also has implications on testing and goals for achieving efficacy. While well-known behavioral problem-solving processes such as Define–Diagnose–Design–Test (Datta & Mullainathan, Reference Datta and Mullainathan2014) and Test, Learn, Adapt (Haynes et al., Reference Haynes, Service, Goldacre and Torgerson2012) suggest the use of low-cost, ethical RCTs as a means to measure and learn from the impact of policy interventions, BPP approaches still typically treat iteration as an opportunity to tinker with solutions in the interest of achieving more effective results for the problem that was initially identified, rather than to adapt them to adjust to new or emergent circumstances. Recentering evaluation as a feedback mechanism to support continual improvement resituates BPP interventions from tactical ends in themselves into strategic inputs that contribute to system-level change, helping policy designers more nimbly modify solutions in accordance with state shifts, knowledge of imminent trends, or observed user behaviors (Swanson & Bhadwal, Reference Swanson and Bhadwal2009) as well as providing fodder to address future challenges (Supplee & Kane, Reference Supplee and Kane2020).

A road map for applying SBPP

Where above we described a general conceptual model for how SBPP might expand on traditional BPP practice, in the following section, we articulate how SBPP can reduce potential interventional brittleness in the context of a specific Covid-19 pandemic behavioral challenge: the vaccination rollout.

Efficiently and equitably distributing the vaccine to inoculate a global population remains both a logistical and a behavioral challenge (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2020), where the latter issue clearly shares key similarities to efforts to encourage flu shots through messaging and scheduling nudges (Chen & Stevens, Reference Chen and Stevens2017; Bruine de Bruin et al., Reference Bruine de Bruin, Parker, Galesic and Vardavas2019). However, other attributes of the Covid-19 vaccination plan indicate that it may be particularly susceptible to contextual, systemic, and anticipatory brittleness. Diverse populations, perceptions, and fears related to the vaccine – ranging from broader antivax views to concerns about side effects, the desire for more proof of efficacy, and skepticism that vaccines developed to combat the original strain will be effective on newly emergent strains – increase the chances that one-size-fits-all interventions will suffer from contextual brittleness. Decentralized and opaque staging and sign-up processes are already compounded by erratic supply and the need to navigate multiple levels of contradictory federal, state, and community guidelines, putting behavioral solutions at immediate risk for systemic brittleness. Finally, unlike the one-and-done flu vaccine, Covid-19's two-dose protocol increases chances of anticipatory brittleness due to a high likelihood of complacency and reduced vigilance maintaining other preventive behaviors such as social distancing after one dose (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Campos-Mercade, Meier and Wengstrom2020) and failures of follow-through to receive the recommended second dose. Further anticipatory brittleness is likely to result from concerns about vaccine effectiveness for viral mutations, as well as predictable misperceptions of cause-and-effect when vaccines given to already-infected individuals are falsely blamed for patient morbidity or mortality. Collectively, this suggests that augmenting traditional BPP tactics with methods that address these forms of potential brittleness (Table 2) can support a more strategic policy approach to Covid-19 vaccination uptake.

Table 2. Applying a strategic behavioral design process.

Designing for heterocontextual effects: generative user research and participatory design

While nudges and traditional behavioral approaches used to increase flu shots provide a helpful starting point, a successful coronavirus vaccine rollout must also consider the variable interpretations of messaging across communities and cultures, as well as issues of access and message legitimacy. Two additional methods – generative user research and participatory design – may prove beneficial as means to broaden BPP practitioners' understanding of both end users and their contexts.

As described above, the use of qualitative data in BPP is not new (Van Bavel & Dessart, Reference Van Bavel and Dessart2018; Ewert & Loer, Reference Ewert and Loer2020), but the addition of more generative ‘design thinking’ qualitative methods as a means to elicit more specific knowledge about disparate user contexts, conditions, and perceptions has only more recently begun to gain traction (Kimbell, Reference Kimbell2016). In contrast to qualitative research such as focus groups to evaluate hypotheses that have already been constructed, generative user research in SBPP is instead conducted at early stages of a project to ensure that problem frames and hypotheses are informed by real-life user needs, (mis)perceptions, and limitations as a means to expand, rather than confirm, practitioners' understanding of the problem to be solved, or even what qualifies as a problem in need of addressing (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2020). Its purpose is not to provide statistically significant data on what works, but to ensure that problem definition and solution development are not reduced to solving for generic or average users, and are instead informed by insight into user constraints, identity, kinship, or even age (Utych & Fowler, Reference Utych and Fowler2020); in other words, where evaluative research can gauge the comparative effectiveness of different message frames, generative research can indicate when, and for whom, messaging tactics are even appropriate. Generative research on Covid-19 vaccination plans that reveals essential service workers hesitate to get vaccinations due to worries about missing work, or at-risk seniors struggle to navigate complex sign-up systems, for example, might suggest that multiple significant practical issues of access must be addressed if messaging nudges to encourage vaccinations are to be maximally useful.

A second means to more strategically reduce contextual brittleness lies in expanding who is included in intervention design, through participatory design. Participatory design activities stem from the notion that involving people as full participants, rather than test subjects, into the framing and design of solutions will result in more strategic, equitable, and contextually appropriate solutions, which improves the perceived relevance and credibility of policy interventions (Bjögvinsson et al., Reference Bjögvinsson, Ehn and Hillgren2012; Blomkamp, Reference Blomkamp2018). When successful, employing participatory design can reduce contextual brittleness by incorporating bottom-up heterogeneous values and perspectives into the framing and conceptualization of interventions at the outset of design. This resituates policymakers from top-down experts who design for – or worse still, design ‘at’ – end users to facilitators who design with them, with the goal of engaging hard-to-reach populations, fostering cooperation and trust between different groups, and informing more contextually valid, transparent, and legitimate solutions (Blomkamp, Reference Blomkamp2018; Trischler et al., Reference Trischler, Pervan, Kelly and Scott2018) and working relationships (Bowen et al., Reference Bowen, McSeveny, Lockley, Wolstenholme, Cobb and Dearden2013).

While participatory methodologies remain somewhat underutilized in BPP critical discourse and practice, an openness to embracing new forms of participant involvement in the development of interventions is evident in new proposals for ‘self-nudging’ (Reijula & Hertwig, Reference Reijula and Hertwig2020), which further decenter the role of policy designers by placing ownership of decision-making and design firmly in the hands of users (Benjamin et al., Reference Benjamin, Cooper, Heffetz and Kimball2020). Applied to a broader set of challenges, an increased application of participatory methods may also help address BPP's tendency to favor nudges or interventions that focus on individual behavior approaches, and which risk ignoring the potential benefits of collective activity when solving large-scale problems. In the case of the vaccine rollout, for example, participatory design sessions that include clinicians and administrative staff in addition to vaccine recipients would bring to light where perceptual and operational barriers across groups align and conflict, increasing the chances that solutions will solve for healthcare professionals as well as end users.

Applying foresight to explore future scenarios: behavioral planning

Given the myriad shifts and evolving narrative of the Covid-19 saga, policy-driven interventions to address the vaccine rollout are highly likely to suffer from anticipatory brittleness. Borrowing from strategic design and futures thinking, a behavioral planning approach draws on knowledge of context and potential shifts to consider likely adaptations, confluent effects, and new and emergent conditions in order to surface three common assumptions or ‘errors of projection’: stability (that interventions function within inherently stable systems), persistence (that system conditions remain the same over time), and value (that definitions of success are universally shared across contexts) (Schmidt & Stenger, Reference Schmidt and Stenger2021). Anticipating soon-to-be events or slowly emergent but plausible near-future conditions can help practitioners mitigate the risks of BPP solutions by allowing practitioners to more systematically identify relevant systems forces and emergent future conditions that may contribute to interventional brittleness before solutions are fully designed or implemented (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Hine and Marks2017).

By playing out the consequences of likely emergent events and the potential impact of policies on other system components and on one another, practitioners can develop more robust design considerations that inform ‘roughly right’ directional hypotheses and solutions at earlier stages of policy development. For example, exploring the proposed Covid-19 vaccine protocol through a behavioral planning lens surfaces several potential complexities and barriers to desired behaviors: while a two-dose protocol provides far greater immunity than a single shot, it also requires users to navigate additional decision-making and action points. This may require developing policies that augment targeted messaging or social norms to boost receptivity and plans to get vaccinated (Lewandowsky et al., Reference Lewandowsky, Cook, Schmid and Holford2021) with interventions to address issues of motivation and access to return for the second dose, such as supplementing messaging with immunization camps or incentives to increase follow-through (Bates & Glennerster, Reference Bates and Glennerster2017). Behavioral planning can also help practitioners play out other common scenarios, such as the potential behavioral implications from living in a mixed household where individuals may receive the vaccine at different times, or ways in which news or anecdotal stories about vaccine side effects may raise or perpetuate hesitation to seek vaccination.

Embracing foresight does not mean adopting automagical interventions based on groundless predictions (Riley et al., Reference Riley, Nilsen, Manolio, Masys and Lauer2015) or predicting away the genuine uncertainty of viral mutations. Rather, the applied use of foresight suggests staying attuned to emergent issues and evolving views – such as increased clarity on the pros and cons of single shot, delayed booster, or double-dose Covid-19 vaccination protocols – to design policy with an eye toward plausible future conditions, rather than only for the present tense or what is already known.

Situating interventions within ecosystems: choice infrastructure and increasing solution resilience

The Covid-19 vaccine rollout is unquestionably a complex ‘system of systems’ challenge that lies at the intersection of public health, economics, governmental policy, and logistics, putting policy interventions at high risk for systemic brittleness. Despite its surface similarity to flu vaccination programs, a fully conceived solution may, therefore, manifest more as system transformation than as a discrete solution (Dorst, Reference Dorst2019), requiring a systems approach that considers existing infrastructures and systems of exchange to reduce the chances that interventions fail due to operational conflicts and limitations, inequitable execution, or inconsistent enforcement (Shore et al., Reference Shore, Nasreddine and Kocher2012; Bothwell et al., Reference Bothwell, Greene, Podolsky and Jones2016; Supplee & Kane, Reference Supplee and Kane2020).

This requires designing for systems-level ‘choice infrastructure’ as well as user-level choice architecture, using analogous or adjacent systems first as inspiration to identify relevant underlying operational mechanisms and user mental models, and secondly, to explore how these might be leveraged or built upon. For example, policymakers tackling the coronavirus vaccine rollout can borrow from structural and behavioral parallels with flu vaccine logistics or interactions to make use of current infrastructures (e.g., where to receive injections; norms of health plan coverage) and build user confidence, while also recognizing where differences (e.g., the need for cold storage; navigating a new sign-up process) require fundamentally new processes and conditions to support desirable behaviors. Additional systems design methods to identify systems of exchange and flows of tangible and intangible assets, such as asset mapping, can help practitioners develop relevant policy components, incentives, and narratives at micro (e.g., individual), meso (e.g., community and municipal), and macro (e.g., health system) scales (Nogueira et al., Reference Nogueira, Ashton and Teixeira2019), building on the presence of potential ‘leverage points,’ or ostensibly small changes within complex systems have outsize influence on downstream behaviors and flows (Meadows, Reference Meadows1999).

Finally, situating BPP interventions within ecosystems requires becoming sensitive toward the multiple, nondeterministic outcomes of interventions themselves. Integrating redundancies – a hallmark of resilience in complex systems – into BPP solutions can act as a fail-safe in cases where individual interventions fail to deliver expected results or need course correction (Howlett, Reference Howlett2019). For example, despite research demonstrating the benefits of using prosocial messages to increase desirable behaviors in response to the pandemic, other sources indicate a need for more engagement than text messages (Favero & Pedersen, Reference Favero and Pedersen2020). This suggests that a complex systems scenario such as the vaccine rollout is even more likely to benefit from multiple reinforcing forms of policy to increase solution resilience, employing existing infrastructural mechanisms or partnerships to support both defensive strategies (e.g., protecting against negative consequences, such as reducing barriers to vaccine access for those at the highest risk) and offensive ones (e.g., introducing persuasive disincentives, such as requiring proof of vaccination to travel).

Evaluating progress toward desired end outcomes: early-stage prototyping and feedback loops

In contrast to flu vaccination interventions, the coronavirus vaccine rollout is already proving to be arduous, erratic, and lengthy: in other words, a perfect storm of potential contextual, systemic, and anticipatory brittleness. This makes it an ideal candidate for iterative evaluation methodologies that capture directional progress and indicators for course correction, such as prototyping and feedback loops.

While RCTs still have a clear role to play in evaluating intervention efficacy, the use of low-fidelity early-stage prototypes can elicit useful feedback before solutions are even complete, helping practitioners identify what needs adjustment when effort – and cost – is still relatively low (Camburn et al., Reference Camburn, Viswanathan, Linsey, Anderson, Jensen, Crawford, Otto and Wood2017; Schmidt & Stenger, Reference Schmidt and Stenger2021). The ability to iterate in the interest of systems-level outcomes may be even more critically important in quickly evolving instances like Covid-19, where second- and third-order implications of interventions occur on an unusually short wavelength and adopting good behaviors like mask-wearing and handwashing have been shown to result in risk compensation (Mantzari et al., Reference Mantzari, Rubin and Marteau2020) and substitution effects (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Guttman-Kenney, Hayes, Hunt, Laibson and Stewart2018; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Bayham, Fenichel and Richter2020). Although the use of prototyping as an evaluative mechanism in BPP has become increasingly common (Hermus et al, Reference Hermus, van Buuren and Bekkers2020), its application as a generative device to test directional or exploratory thinking when formulating public policies or design public services is still fairly nascent (Mintrom & Luetjens, Reference Mintrom and Luetjens2016; Kimbell & Bailey, Reference Kimbell and Bailey2017; Bason, Reference Bason2019; van Buuren et al., Reference van Buuren, Lewis, Guy Peters and Voorberg2020). However, this notion of prototyping concepts, rather than solutions, can also provide significant benefit to the development of more SBPP; just as participatory design embeds broader perspectives into solution development, prototyping early thinking to inform problem definition can better ensure that eventual policy interventions are solving for the right things.

Achieving increased solution resiliency also implies having time to respond as contexts change and adaptation sets in (Nair & Howlett, Reference Nair and Howlett2016). Where RCTs provide evidence-based proof of efficacy and prototyping can enrich solution development processes, a third form of evaluation – feedback loops – can supply ongoing insight into policy effectiveness through the use of lagging and leading metrics. Traditional BPP metrics of success tend to be lagging; while helpful in gauging uptake or behavioral change, they typically provide a backward-looking view to indicate the extent to which policy interventions have worked. In contrast, leading metrics signal more emergent conditions and ‘weak signals’ (Ansoff, Reference Ansoff1975), providing an early warning system about the state of system conditions and user behaviors that widens the window of opportunity between initial indications of system breakdowns and their full emergence, and allowing those responsible for the system to act earlier on the delay (Meadows, Reference Meadows1999).

Leading metrics in environmental policy environments have long been emphasized by the European Environment Agency, which posits that deep uncertainties at the time of policy creation can be reduced if policymaking is adaptive and sensitive to relevant changes (European Environment Agency, 2001). Leading metrics can also provide critically important insight into contexts where important indicators require noting the absence of events, infections, and fatalities that do not occur. In the vaccine rollout context, for example, leading metrics indicating low utilization of digital tools to schedule vaccination appointments might signal the need to address flaws in the sign-up program far in advance of capturing lagging metrics in the form of a low percentage of administered doses. Finally, attention to leading metrics can also help surface anomalies or ‘Black Swan’ events and emergent trends that would otherwise be ignored or dismissed, identifying potential opportunities for course correction or strategic adaptation at earlier stages of development and implementation (Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, Leonard and Mikes2020).

Potential considerations and a path forward

Although this article primarily uses Covid-19 as a means to define, illustrate, and address the phenomenon of brittleness in BPP methodology, this should not be perceived as either a boundary on areas at risk for brittleness or the limited applicability of SBPP. On the contrary, interventional brittleness that would benefit from strategic methodology can be found in many other BPP settings presenting a high degree of systems complexity, such as sustainability or other public health challenges. Regardless of the area of application, however, adopting a SBPP approach will require overcoming two strong but interrelated tendencies at the heart of current methodological traditions: the propensity to seek precision in problem definition as a means to achieve rigor, but at the potential expense of broader effectiveness, and a predisposition to see behavioral challenges predominantly as the domain of analytical problem-solving, rather than eliciting expertise of a wider range of disciplines.

The limitations of behavioral science methodologies and nudging are well recognized, even by its advocates (Thaler, Reference Thaler2017; Reijula et al., Reference Reijula, Kuorikoski, Ehrig, Katsikopoulos and Sunder2018), but – in the parlance of business strategy – perceived constraints on BPP's ‘where to play’ (i.e., which problems to address) and ‘how to win’ (i.e., how to solve them) may also be somewhat self-imposed (Lafley & Martin, Reference Lafley and Martin2013). BPP's proven track record tackling last-mile challenges has contributed to a steady diet of more of the same; over time, this has led to a kind of tautological standoff, where the nature of problems that BPP is tasked with solving are those that current methodology happens to solve well, but which has also inadvertently contributed to typecasting BPP as a discipline fit to address only certain types of problems.

If anything, however, Covid-19 and other large-scale public health and sustainability challenges indicate that insights used to inform BPP interventions are as applicable to complex conditions as they are well-defined and predictable ones, but also that policymakers must develop new appetites for methodologies that embrace, rather than excise, uncertainty (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Snijders and Hallsworth2018; Spencer, Reference Spencer2018), and for qualitative data that provide directional, rather than confirmatory, evidence in order to address them. While this may feel at odds with traditional BPP notions of evidence-based rigor, it is not inconsistent with more sociological and sociotechnical views on human behavior that take a more expansive view of the social contexts and constructs in which people interact (Bruch & Feinberg, Reference Bruch and Feinberg2017; Ewert & Loer, Reference Ewert and Loer2020).

Solving for this tension may, therefore, be closely tied to developing an increased appetite for interdisciplinarity, with SBPP or ‘advanced’ versions of the discipline (Ewert & Loer, Reference Ewert and Loer2020) expanding on, rather than replacing, current notions of how to solve challenges and who gets to solve them. Despite plentiful research suggesting that diverse groups outperform homogenous groups (Hong & Page, Reference Hong and Page2004; Phillips, Reference Phillips2014), BPP has tended to maintain largely insular ownership over behavioral policy problem-solving methodologies. Even when BPP has looked beyond its own discipline, invitations to collaborate have primarily been extended only to other social sciences or analytically driven disciplines like data analytics as partners (Feitsma & Whitehead, Reference Feitsma and Whitehead2019). This indicates that, somewhat ironically, practitioners who are steeped in an awareness of cognitive biases may still suffer from disciplinary partisanship and limited epistemological networks (Brister, Reference Brister2016) that prevent them from seeing the value of further adjacent disciplines.

Given the value of systems thinking and foresight in tackling complex BPP challenges, becoming more strategic may also require turning to disciplines that are inherently more comfortable and effective in navigating complexity and ambiguity (Buchanan, Reference Buchanan1992). The fields of ‘design thinking’ or human-centered design already contribute lightly to behavioral problem-solving through insight into end-user contexts and notions of empathy, but their potential to contribute more substantive input into hypothesis and solution development in a policy context has yet to be fully conceptualized and developed (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2020). Encouragingly, ‘design science’ has more recently become recognized within public policy and public administration as worthy of study and application (Shangraw & Crow, Reference Shangraw and Crow1998; Barzelay, Reference Barzelay2019; George, Reference George2020; Hermus et al., Reference Hermus, van Buuren and Bekkers2020). Still, making BPP problem-solving more strategic may require recentering hypothesis development and problem-solving from a singular and top-down activity owned by behavioral policymakers to a more broadly collaborative one.

Conclusion

In this article, we suggest that employing traditional BPP methodology to address system challenges is likely to introduce three forms of brittleness – contextual, systemic, and anticipatory – into solutions. To correct for these forms of brittleness and achieve greater solution resilience, we propose a methodology for SBPP that expands on current methodological approaches. We then use the Covid-19 vaccination rollout to detail a methodological road map describing how BPP practitioners might develop more strategic solutions in practice and conclude by indicating potential limitations and the necessity of expanding beyond a tight disciplinary mindset if this approach is to be adopted.

Embracing a shift to SBPP may initially seem daunting, even far-fetched. But the Covid-19 pandemic not only supplies plentiful examples of brittle policy interventions; it also highlights BPP's willingness to adapt disciplinary assumptions. The field's collective desire to combat the pandemic has galvanized the efforts and expertise of the international BPP community, prioritizing collaboration, easier access to information, and speculative early results in the form of preprints over the usual norms of peer review (Final Mile, 2020; Matias & Leavitt, Reference Matias and Leavitt2020; Tidwell, Reference Tidwell2020). In such an urgent context, the field's recognition that it is worthwhile to trade by-the-book precision for ‘roughly right’ processes provides some hope that the similarly nontraditional path of BPP to address contextual, systemic, and anticipatory brittleness can be seen in an analogous light.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their comments and guidance that substantially improved this article.