Introduction

Peer support groups were designed to enable opportunities for people to connect, share their experiences, seek emotional support, and share useful information with others as well as instilling hope (Dennis, Reference Dennis2003). There is evidence to suggest that such programmes can improve symptoms of depression, in some cases at a level comparable to group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT; Pfeiffer et al., Reference Pfeiffer, Heisler, Piette, Rogers and Valenstein2011), and that they can improve social networks and perceived social support (Castelein et al., Reference Castelein, Bruggeman, Van Busschbach, Van Der Gaag, Stant, Knegtering and Wiersma2008). In the context of advances in digital technology and people connecting using a variety of online platforms, it is possible that online peer support groups focusing on mental health support may be particularly helpful in reducing stigma and isolation for individuals who may be struggling with their mental health but who feel less able to access support from others in person (see Melling and Houguet-Pincham, Reference Melling and Houguet-Pincham2011). Possible stigma-related barriers to help-seeking include shame/embarrassment, negative social judgement, disclosure/confidentiality concerns, and employment-related discrimination (Clement et al., Reference Clement, Schauman, Graham, Maggioni, Evans-Lacko, Bezborodovs, Morgan, Rüsch, Brown and Thornicroft2014).

Online peer support platforms evolved in part from the impact of social media, which provided a platform for individuals with mental health problems to share their experiences and offer words of encouragement or advice (Naslund et al., Reference Naslund, Aschbrenner, Marsch and Bartels2016). However, social media has also been linked with negative mental health consequences such as increased stress or symptoms of anxiety and depression, although empirical findings are mixed (see Karim et al., Reference Karim, Oyewande, Abdalla, Ehsanullah and Khan2020; Meier and Reinecke, Reference Meier and Reinecke2021). It is possible therefore that alternative platforms may be considered more clinically appropriate. The extent of research evidence on online peer support is at present relatively limited, and findings to date are mixed; studies have generally found benefits regarding social connectedness, personal empowerment, and quality of life, although significant improvement is less common when validated clinical outcome measures are used (Easton et al., Reference Easton, Diggle, Ruethi-Davis, Holmes, Byron-Parker, Nuttall and Blackmore2017). Studies have most commonly examined interventions for those with specific physical health conditions, severe mental health problems (e.g. Naslund et al., Reference Naslund, Aschbrenner, Marsch, McHugo and Bartels2018), or young people’s mental health (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Farrer, Gulliver and Griffiths2015). There are fewer studies that examine such programmes in relation to adults with mild to moderate depression and anxiety, so it is less clear whether they may be helpful for this client group.

The extent of evidence evaluating the user experience of such platforms is also limited. Griffiths et al. (Reference Griffiths, Reynolds and Vassallo2015) examined posts on one moderated platform for depression, finding that 77% of the posts studied outlined perceived user advantages such as how posting messages led to positive emotional, cognitive or behavioural change for the user, valuing the opportunity to socialise and be supported by others, and sharing how they are feeling. Twenty-three per cent of posts identified disadvantages such as negative personal impacts, unhelpful interactions with others, and technical difficulties (see also Easton et al., Reference Easton, Diggle, Ruethi-Davis, Holmes, Byron-Parker, Nuttall and Blackmore2017). Other studies have identified similar potential advantages by analysing forum posts (e.g. Horgan et al., Reference Horgan, McCarthy and Sweeney2013; Prescott et al., Reference Prescott, Hanley and Ujhelyi2017). Although the posts on online platforms provide a rich source of data, they may not represent the experiences of all users, such as those who do not wish to post messages or might not feel comfortable to do so; it is important to understand the different ways people use such platforms and how they feel about using them, but at present these topics are under-researched.

Support, Hope and Recovery Online Network (SHaRON) is an online peer support platform, moderated by clinical staff, that aims to facilitate peer support among individuals with mental health conditions. It was developed by Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust in 2009. SHaRON is available via computer and mobile devices and is offered across a number of mental health services including those in the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme, perinatal services, eating disorder services, and other community mental health settings. Each service has their own individual SHaRON platform with resources and information forums aimed for the appropriate users. The Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire IAPT shared platform (see Fig. 1) contains CBT resources including thought and activity diaries, materials to help identify and work with patterns of unhelpful thinking, NHS-approved CBT-based apps and websites as well as signposting to a range of local services. Alongside these resources, members can post messages on the platform (all members use pseudonyms to ensure privacy), and read blogs and forum posts from others who have experienced similar difficulties and are now feeling better. It therefore aims to provide an opportunity to connect with people further along their recovery journey and thus instil hope. The site is moderated by qualified IAPT clinicians including psychological wellbeing practitioners and cognitive behavioural therapists who monitor activity as well as sharing CBT-based tips for overcoming anxiety and depression symptoms, and maintaining wellbeing. All moderators have completed a 2.5-hour training workshop which includes guidance on reviewing and responding to users’ posts, managing clinical risk, and using their clinical skills on the platform. Staff moderation follows a rota structure, with four time slots each day within the operating hours of the services. During each assigned slot, the moderator is expected to spend around 15 minutes reviewing platform content.

Figure 1. User dashboard of the SHaRON platform.

This study aimed to evaluate users’ experiences of the Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire IAPT SHaRON platform, examining their use of site features, feelings about using the platform, and the areas they find helpful, unhelpful, or could be improved.

Method

Design

The study used a survey for the purpose of data collection. SHaRON is a shared platform between Healthy Minds (Buckinghamshire) and TalkingSpace Plus (Oxfordshire) IAPT services. Therefore, survey questions were generated and developed by clinical staff across both services. This included clinical psychologists, CBT therapists, and psychological wellbeing practitioners. As this study was exploratory in nature, the survey was designed to elicit information across the following topics: respondents’ use of platform features, feelings about using the platform, and users’ overall experience. The survey also provided space to answer qualitatively about reasons for lack of use (if relevant), their experiences, and any suggestions for improvements.

Participants

Participants were clients from either the Buckinghamshire or Oxfordshire IAPT service, who had either completed, or were currently undertaking treatment. All clients had opted-in to be referred to SHaRON and had accessed the programme at least once prior to the survey opening. Participants were recruited from 24 September 2021 to 22 October 2021 via email or posts within the platform. All participants were over the age of 18 with no upper age limit, and either were currently, or had previously experienced symptoms of depression and/or anxiety. The survey was conducted in English and participants needed access to the internet either via computer or mobile phone. In total, 923 SHaRON users were initially invited via email to participate in the survey. Nine users requested to be removed from mailing lists after the first invitation and were excluded from subsequent reminder emails.

Procedure

The study was approved by and registered with the NHS Trust Quality and Audit team. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and did not involve incentives or compensation. This was done to promote and encourage participants to respond freely and openly with critiques and ideas for improvements. The survey was hosted on the Microsoft Forms platform. An initial invitation email was sent to all clients on the user database for Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire’s shared platform, excluding those who had previously opted out. The survey remained open for 28 days and during that time two reminder emails were sent. In addition, three posts were made on the online platform with information and links to the survey. A similar post was also pinned to the top of all users’ newsfeeds for the duration the survey was open.

The quantitative data collected was analysed descriptively using Microsoft Excel. The qualitative data gathered in response to each structured free text question were analysed using a thematic analysis approach, which offers a flexible method for describing and summarising such data (see Swart, Reference Swart2019), as was appropriate to the aims of this study. While these questions guided respondents towards topics chosen by the study team, they were open-ended, which permitted a data-driven pragmatic approach. The analysis followed the phased approach outlined by Nowell et al. (Reference Nowell, Norris, White and Moules2017). Initially, all responses to each question were read through to develop familiarity with the data. A preliminary coding framework was then developed by two of the authors (N.O.C. and G.R.T.), based on independent coding of the data and subsequent discussion. This was performed separately for each free-text survey question, without reference to respondents’ other survey data. The preliminary codes were subsequently discussed with the wider project team as part of an iterative process in order to identify themes. Responses were then categorised into the themes identified (by N.O.C.). Where a response contained several statements which fitted across different themes, more than one theme was used. However, each individual statement within a response was only categorised once. Once all responses were categorised, results were again taken to the whole team for review and refinement of the themes where appropriate. Possible superordinate themes were considered, but given the limited number of themes per question, and the variety in their content, we felt they were not necessary for characterising the data. We have chosen to present the themes for each question in order of the frequency of comments made under each theme; this may be of use or interest to those running similar studies in future. We note, however, that the frequencies were not formally examined within the analytic procedure.

Results

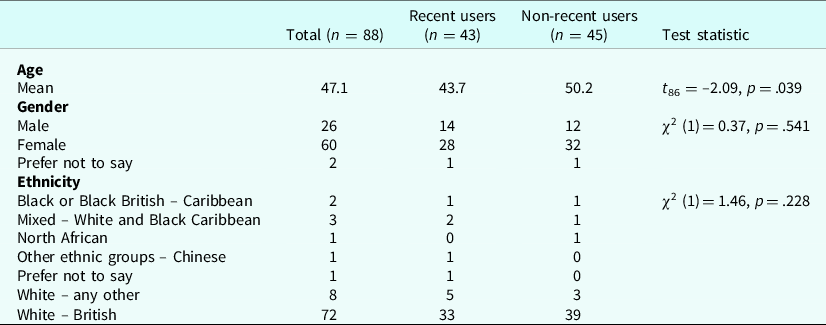

The survey was completed by 88 respondents. Forty-three reported having used SHaRON in the past 3 months. With respect to the overall number of invites sent, this represented a low response rate of 10% (88/923). However, a review of activity data over the 4-month period prior to the survey showed that the number of active unique users on the site was 143. This suggests that the survey results were representative of approximately 30% (43/143) of active users, with the additional 45 responses representing the views of those who have not used the platform recently (though may have used it regularly prior to this). Demographic information is shown in Table 1. The group of respondents who had not used the platform in the past three months was significantly older than the group of recently active respondents, by an average of 6.5 years. No significant group differences for gender or ethnicity were observed.

Table 1. Demographics of the survey respondents

Chi-squared test for Gender compared Male vs Female; chi-squared test for Ethnicity compared White British vs other response (collapsed due to small cell counts).

Use of platform features

A series of questions asked respondents to rate how often they use different features of the platform, using a scale from 1 (never) to 10 (always). Responses from the whole sample indicated that the majority of users (63%; 55/88) reported posting a message on the platform at least infrequently, with 31% (n = 27) doing this more regularly, giving a rating of 6 or higher. Similarly, 55% (n = 48) reported taking part in a discussion on the platform, with 26% (n = 23) giving a rating of 6 or higher. In contrast, the ability to send a private message to another user was used much less often; only 30% (n = 26) of respondents reported that they use this function, with only 11% (n = 10) giving a rating of 6 or higher.

Two-thirds of respondents (66%; 58/88) reported that they read discussions from other users while on the platform, with 48% (n = 42) giving a rating of 6 or higher, suggesting that consumption of content on the site may be more common than users generating new content. However, this trend was not observed so strongly in relation to reading the resources on the platform such as the discussion forums; 47% (n = 41) reported that they did this, with 20% (n = 18) giving a rating of 6 or higher.

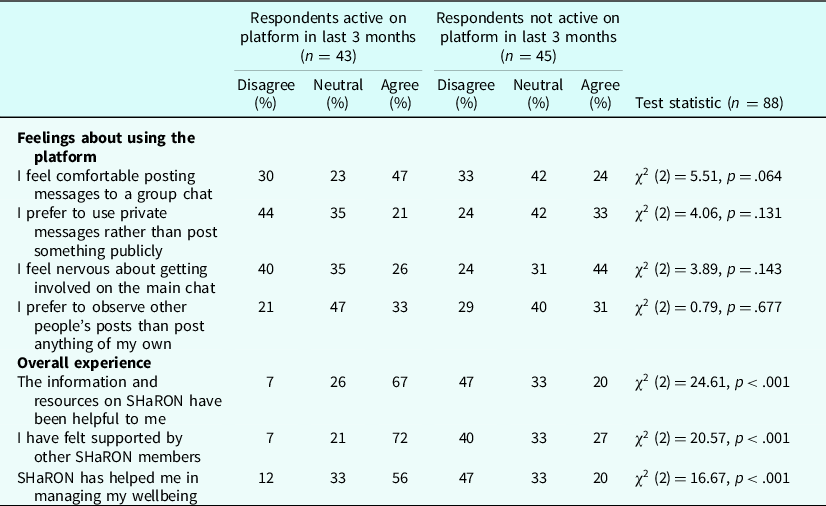

Feelings about using the platform

Respondents were asked about their preferences and feelings in relation to different activities on the platform, using a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The proportions of disagree (1 or 2), neutral (3) and agree (4 or 5) responses are shown in Table 2, dividing the sample based on whether they reported using the platform in the past 3 months. A range of responses was observed in both groups. Comparison of the two suggested that a greater proportion of respondents who had not used the platform recently were less comfortable posting messages to a group chat and felt more nervous about getting involved on the main chat, compared with recently active respondents, although chi-squared tests did not indicate that these differences were significant.

Table 2. Percentage of respondents agreeing or disagreeing with survey items

Disagree represents the percentage of respondents choosing ‘strongly disagree’ or ‘disagree’ in relation to each item; Neutral represents the percentage choosing ‘neither agree nor disagree’; Agree represents the percentage choosing ‘strongly agree’ or ‘agree’.

Overall experience

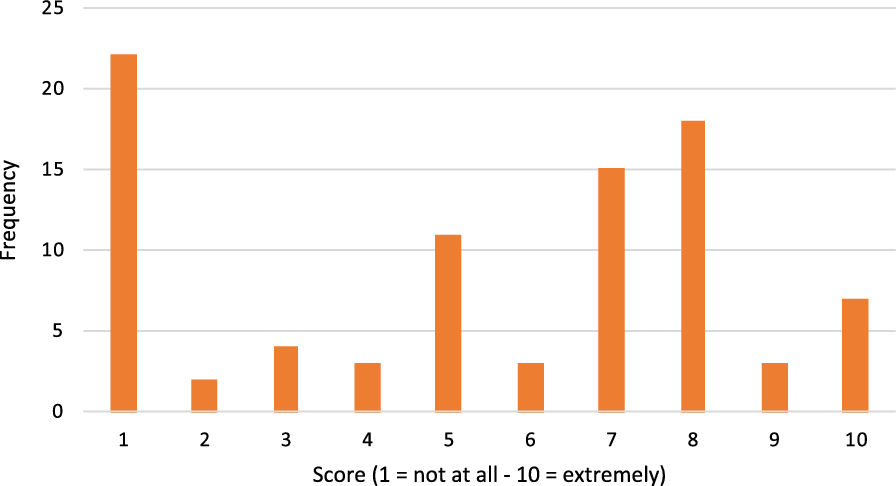

A series of rating scale and free response questions was used to examine participants’ overall experience of the platform. Responses to the rating scales are shown in Table 2. The majority of recently active participants agreed that they had found the information and resources on the platform helpful, felt supported by other users, and felt that it had been helpful in managing their wellbeing. Respondents who had not used the platform in the past 3 months gave significantly less positive responses, most commonly disagreeing with these statements. When asked to rate the overall helpfulness of SHaRON using a scale from 1 (not at all) to 10 (extremely), a bi-modal distribution was observed, with peaks at 1 and 8 (see Fig. 2). However, all but one of the respondents who gave a score of 1 had not used the platform in the past 3 months. This indicates that the platform is not helpful for everyone, but of those who used it within the last 3 months, a majority (81%; 35/43) would describe it as helpful, giving a score of 6 or higher. It is also noted that 24% of respondents who had not used the platform in the past 3 months (11/45) gave a score of 6 or higher, which indicates that it is possible for users to find the platform helpful even though they may not use it frequently.

Figure 2. Frequency chart showing responses to the question ‘Overall, how helpful is SHaRON to you?’.

Respondents were asked to indicate using a free text box what they think makes the platform helpful. Responses reflected the following themes.

Friendly community

A common theme (15 participants) was that there was a sense of a supportive and friendly community on the platform, and that this made it feel easier to share their own feelings and difficulties:

‘It’s a place I can come to without feeling judged. Everyone appears to be so supportive of others.’ (Respondent 49)

Accessing support

Fourteen participants commented on the support they have received by using the platform, either by posting comments about difficulties they have been experiencing or by learning from others:

‘I have only posted a couple of things so far, but the responses from both moderators and users have been very supported and useful.’ (Respondent 50)

In addition, one respondent described their experience of supporting others:

‘It’s really good to be able to express yourself. For me I like supporting others in the chat and pass on what works for me. Especially as no one knows each other.’ (Respondent 51)

Normalising

Responses from 13 participants indicated that it was helpful to know that others are feeling similar to them, and that this made them feel less alone:

‘The main thing for me was realising I wasn’t struggling on my own. It also helped me think about what I could do to help myself.’ (Respondent 75)

Knowing the support is there

Ten participants indicated a benefit of simply knowing that the platform is there and that support is available if required, even if they might not use it regularly:

‘Even though I don’t come here all the time. I feel safe in knowing I have a space to come to if I need it.’ (Respondent 60)

Information and resources

Eight participants commented on the helpfulness of the information and resources available on the platform:

‘It’s another tool to use when having a bad day. Others on there give reminders of CBT tips and techniques.’ (Respondent 78)

Helpful moderation

Responses from three participants highlighted the value of staff moderation on the platform (e.g. to prevent bullying) or the responsiveness of the moderators:

‘There always seems to be someone there to answer, even if it is sometimes after a day or two after your post.’ (Respondent 32)

When asked whether there was anything they find unhelpful about the platform, or could be improved, most participants (58%) said ‘no’. Responses in the free text box relating to this question reflected the following themes.

More content and activity

Responses from nine participants related to the amount of content and activity on the platform, including comments regarding a lack of content, as well as comments requesting more:

‘More engagement and involvement. Daily themes getting people to interact more?’ (Respondent 4)

Improving accessibility and user-friendliness

Eight participants indicated that the ease of accessing the programme, or general user-friendliness, could be improved:

‘It didn’t work very well on my phone. Text was quite small and it looked like it was designed for use on a computer not a phone. Having said that, my phone is quite old.’ (Respondent 75)

Technical improvements and new features

Seven participants made specific suggestions for technical improvements to the platform or new features to implement:

‘Bit more colourful would be great, might make the site more engaging. Polls would be a good idea too maybe.’ (Respondent 51)

Not helpful for me

Five participants indicated in general that they did not find the platform helpful, without going into specific detail:

‘I think it may be useful for some people but I personally didn’t find it that helpful for me.’ (Respondent 70)

Improved user guidance

Responses from four participants suggested that the guidance for using the platform could be improved, particularly for new users:

‘I do not routinely use social media, such as Facebook, so I have struggled to work out how to best use SHaRON, so some more simple instructions would be useful for me, including how to access resources.’ (Respondent 50)

Moderator responsiveness

Two participants indicated a need for improving the responsiveness of moderators:

‘More involved moderators.’ (Respondent 71)

Reasons for lack of use

The 45 respondents who indicated that they had not used SHaRON in the past 3 months were invited to share their reasons for this. Responses reflected the following themes.

Feeling better and don’t need it

Thirteen participants reported that as they now felt better, they had less need to access the platform:

‘I found it useful at the beginning, however as my own anxiety improved I didn’t go back on.’ (Respondent 39)

Technical or access difficulties

Responses from 11 participants indicated they had not used the platform recently due to finding the site difficult to access or confusing to navigate:

‘I never really got the hang of it to be honest.’ (Respondent 6)

Forgot about it

Seven participants indicated they had forgotten about the platform since originally signing up:

‘After initially joining I have completely forgotten about it.’ (Respondent 1)

Too busy

Six participants indicated they had been too busy to use the platform:

‘2 new puppies, lack of sleep, no time for myself.’ (Respondent 44)

Didn’t find it helpful

Responses from five participants indicated they did not find the platform helpful:

‘I didn’t find that it was helpful to me.’ (Respondent 11)

Lacking content

Five participants mentioned that there was less activity or content on the platform than they were expecting. It is possible that these participants were some of the first to join the platform.

‘Didn’t seem to have an uptake of people using chatting and responding.’ (Respondent 3)

Found it overwhelming

Responses from two participants indicated that they found using the platform stressful or overwhelming:

‘I only used it once. When I logged on there were so many messages from other users – all very positive – but it felt like I hear about Facebook and other social media all wanting likes etc. I do not use social media and had no idea how to reply or engage. It was too stressful so as I was trying to overcome stress I decided it was not for me.’ (Respondent 14)

Discussion

Overall, the results highlighted that most features of the SHaRON platform were generally well used, with the exception of private messaging, and that many of the participants felt supported by other users and found the available information and resources on the platform were helpful to them. Consistent with previous findings (e.g. Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Reynolds and Vassallo2015; Prescott et al., Reference Prescott, Hanley and Ujhelyi2017), the majority of participants in this study reported feeling that the platform was a helpful tool in the management of their wellbeing. Participants’ comments highlighted a number of advantages to using the platform, in particular the friendly and supportive environment, and the normalising effect of hearing that others may be experiencing similar difficulties. Additionally, participants reflected on the valuable and easily accessible source of support that the platform provided. This is in line with Prescott et al. (Reference Prescott, Hanley and Ujhelyi2017), that such platforms are a convenient way to access information as and when required, on a 24/7 basis. These findings raise a number of interesting empirical questions, such as who might benefit most from using the platform, and whether clinical outcomes in IAPT might be enhanced by using it, perhaps through greater clinical improvement, faster improvement, or better maintenance of treatment effects. The platform appears to offer an ongoing source of support that has the potential to achieve these aims, and future studies examining these questions are warranted.

However, the present results also indicate that some individuals felt less comfortable or nervous about posting messages publicly on the platform, and it is possible that this prevented them from engaging with and using it regularly. Future research may usefully examine in more depth the reasons for or potential barriers to doing this. A number of participants indicated that they did not find the platform beneficial for them. This may have been related to feeling overwhelmed or technical difficulties, but also perhaps indicates that the online platform format is not for everyone. Around half the survey respondents had not used the platform in the past 3 months, although the reasons for this were varied, and comments most frequently reflected the theme that people felt they no longer needed it because they were feeling better. Interestingly, the findings have shown that there may be a broader perceived sense of support that users can find helpful even if they are not accessing the platform regularly. Respondents described that simply knowing that the support is available is helpful, and this is supported by the finding that 24% of those who had not used the platform recently still rated its helpfulness as 6 or more out of 10. This perceived sense of available support represents an interesting psychological phenomenon that may warrant further investigation.

This study has also identified a range of feedback and suggested changes that will be used to enhance SHaRON and may be of help for those who are designing or developing similar platforms. These include the following:

Firstly, ensure there is plenty of up-to-date content and frequent activity evident on the platform. Horgan et al. (Reference Horgan, McCarthy and Sweeney2013) emphasised the importance of posting ‘frequent and relevant’ information to entice users to contribute. The present findings suggest this is important in shaping users’ experience. Secondly, provide clear, simple and easily visible guidance on how to use the platform, including both technical and navigation guidance, but also advice on contributing, for example what you might say in a post. This is perhaps most relevant for new users but may help those who are less confident with technology or who are returning to the platform after a break. Thirdly, consider whether the function to send a private message to another user should be made available. This was rarely used in the present study and two comments indicated they would like the ability to turn this off. Lastly, the present results suggest that it can be easy for users to forget about the platform so it may be helpful to arrange reminders for registered users to promote platform activity and an up-to-date user database.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the present study include the anonymity of the survey, the inclusion of questions specifically designed to elicit negative feedback, and the focus on the use of specific features and feelings about using the platform. It also aimed to elicit responses from those who had not used the platform recently, and this group was relatively well represented, which permitted a helpful examination of the reasons for this. The main limitation of the study is the low response rate; it is perhaps probable that the majority of invitees had not used SHaRON since creating their account, but we were keen to gather responses from this group so aimed to be inclusive during recruitment. It is possible that some email invitations may have been filtered as junk mail, although efforts were made to avoid this. Results may therefore not fully capture the views of all users, although the representation of recent platform users was better, and more in line with survey response rates in similar studies. The low proportion of recently active users relative to the user database (143/923) could reflect people forgetting about the platform, no longer needing it, only using it occasionally, or creating an account but never becoming a regular user. Responses from participants from non-white British ethnic backgrounds were under-represented in the present sample relative to the local population. Another possible limitation is that some users were using the platform relatively soon after its launch, meaning there would have been less content and activity compared with users who joined later. Continued efforts to invite new users to the platform, and to train further moderators, including ‘peer’ moderators with personal experience of treatment, will help to promote regular activity and new content. This was an original survey that has yet to be externally validated; further use would help to confirm the reliability and generalisability of the present findings. Lastly, the present survey did not directly examine users’ feelings about the anonymity of the platform, or experience of moderation; these may be helpful topics to address in future studies.

Conclusion

This study has evaluated users’ experiences of the SHaRON platform, examining their use of site features, feelings about using the platform, and the areas they find helpful, unhelpful, or could be improved. A number of advantages and helpful aspects of the platform were identified, consistent with existing literature. The findings extend previous work by highlighting the broader range of user experiences, such as some who feel less comfortable writing on the platform, and some who do not regularly use the platform but experience a perceived sense of support through knowing it is there.

Key practice points

-

(1) Online peer support platforms can provide a helpful and accessible source of information, resources and support to enhance mental health and wellbeing during and after psychological therapy.

-

(2) Present results suggest the format does not suit everyone, and that people may use it less as they start to feel better.

-

(3) There may be an important psychological benefit to such platforms in terms of knowing the support is available, even if it not used regularly.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, N.L.B. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study participants, the SHaRON HQ team, and staff from the digital teams in the participating IAPT services.

Author contributions

Natasha Browne: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Nick Carragher: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Visualization (lead), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Annette O’Toole: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); John Pimm: Conceptualization (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Joanne Ryder: Conceptualization (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Graham Thew: Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Methodology (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (lead).

Financial support

This work was supported by the Oxford Health NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Conflicts of interest

Graham Thew is an Associate Editor of the Cognitive Behaviour Therapist. He was not involved in the review or editorial process for this paper, on which he is listed as an author. The other authors have no declarations.

Ethical standards

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. External ethical approval was not required for this service evaluation study; the project was reviewed and approved by the local NHS Trust Quality and Audit team.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.