1. Summary of Paper and Conclusions of the Working Party

1.1. Solvency II

Solvency II has been under consideration and development since the early 2000s. The previous regime, in force since the 1970s (which had come to be known as Solvency I), was not risk-sensitive and a number of key risks, including market, credit and operational risks, were not explicitly taken into account in capital requirements. Furthermore, Solvency I permitted the continuation of different methodologies in different EU countries, e.g., either book or market value of either assets or liabilities, depending on country.

The lack of risk sensitivity introduced problems ranging from inaccurate assessment of risks requiring supervisory intervention to a sub-optimal allocation of capital relative to the risks being borne. The Solvency II framework proposed to remedy these shortcomings of Solvency I.

Appendix 2 gives an overview of the evolution of Solvency II, including future plans, together with a summary of past and current issues.

1.2. The Working Party

In November 2015 our working party was established with the aim of producing a sessional paper to consider Solvency II’s objectives and assess the outcome of the final regulations against its key objectives which include:

-

∙ improved protection of policyholders and beneficiaries;

-

∙ harmonisation;

-

∙ effective risk management; and

-

∙ financial stability.

As part of that process, meetings were held in London and Edinburgh to gather views from the profession. A workshop was also held at the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries Life Conference in 2016 in which we shared an overview of Solvency II’s strengths and weaknesses and conducted a survey to seek the views of the attendees (see Appendix 1).

One of the outcomes of these meetings is a realisation that there is no single prevailing view within the profession. In a similar vein, where there is common acceptance of issues coming out of Solvency II there is no single answer to these – more a range of potential solutions.

This paper focusses on life insurance business. Non-life, health and reinsurance business have not been considered. This paper also focusses mainly on the UK, but aspects from other countries have been considered where possible.

One of the goals of the working party has been to inform the debate on Solvency II ahead of the 2017 review by the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) (see Appendix 2 section 2).

As at the end of 2015, insurers and reinsurers in the UK had invested £3bn in the Solvency II Directive, according to the Association of British Insurers (2015). Preparation and transition to the Directive has been a costly exercise with various delays introducing changes in the original rules. Whilst there are lessons to be learned from the way that Solvency II was introduced and the costs associated with it, our working party has chosen not to explore the process of implementation.

The investment has been made and we now have a regulatory regime that is appropriate for a modern insurance industry and current technology.

In the United Kingdom, Brexit has added a new dimension to the debate, causing the Treasury Select Committee (TSC) in the United Kingdom to look at European insurance regulation and to consult on its suitability for the United Kingdom. Our working party, along with the practice boards and other relevant working parties, had an input into the profession’s written response to the TSC’s consultation (Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA), 2016).

1.3. Efficiency and Competitiveness

Solvency II seeks to equalise the level of competitiveness and foster the development of an internal market across Europe. Consequently EIOPA has some regard to absolute competitiveness, although the outcome of Solvency II suggests that the latter appears to have been limited. As pointed out by the TSC, the Prudential Regulatory Authority (PRA) has within its primary objectives no remit in respect of competitiveness and questioned whether this was appropriate (Treasury Committee, 2017). This is relevant because there are a number of burdensome and costly aspects of Solvency II that can affect profitability, discourage new entrants and reduce the competitiveness of the industry.

For example, in respect of annuity business:

-

∙ Investment return opportunities are reduced through ineligibility of assets such as Equity Release Mortgages.

-

∙ The consequent need to package such assets to meet eligibility rules increases costs and absorbs resources.

-

∙ Tighter cash flow matching requirements than under Solvency I and other eligibility rules also increase costs.

-

∙ Restrictions on the trading of bonds reduce profitability.

The standard formula has deficiencies, which require firms to seek Internal Model Approval, and it is difficult to change, so it may inhibit innovation.

Approval processes – such as the internal model approval process (IMAP) and approval to use the matching adjustment (MA) – need to be made more efficient. Currently they are lengthy, costly and burdensome.

Furthermore, the current process to introduce changes to the internal model potentially inhibits innovation.

1.4. Market Consistent Valuation, Capital and Risk Margin

Solvency II is a comprehensive programme of regulatory requirements for insurers, covering authorisation, corporate governance, supervisory reporting, public disclosure, risk assessment and management, as well as solvency and reserving. It is one of, if not, the most sophisticated regulatory regimes in the world. As a consequence we cover these aspects in some detail in sections 2 and 3.

Solvency II’s foundation for the calculation of technical provisions and capital requirements is market consistency. Omnibus II recognised that for long-term guaranteed business a number of shortfalls and political concessions would be required to make Solvency II acceptable to the member states.

From a product perspective, annuity business is probably the most important long-term guaranteed business written in the United Kingdom. Here it was recognised that it was default risk rather than spread risk that was the principal credit risk and this was accommodated through a higher discount rate linked to the assets owned and lower capital requirements.

This clear break from market consistency now makes it possible to reduce technical provisions by taking on credit risk. It also means that a significant proportion of the UK’s long-term guaranteed business is still valued on a basis that has similarities with the Solvency I regime.

It raises the question as to whether market consistency is a useful tool to provide a general approach or whether it is an end in itself. There may be flaws in following a dogmatic market consistent approach but it is through market consistency that effective risk management is rewarded.

Its design moved us to a framework that has demanded a true best estimate of the liabilities with a requirement to hold enough capital for a 1 in 200 year worst-case outcome. The assumption is that recapitalisation, perhaps through acquisition, can be achieved with a 12-month timeframe. This can be viewed as a “going concern” basis rather than a “run-off” basis with prudent margins (Swain & Swallow, Reference Swain and Swallow2015).

For annuity business, the size and volatility of the risk margin has been thrown into the spotlight by the current low interest rate environment. This is giving rise to a number of issues and questions being raised around the rationale and logic of the risk margin along with potential solutions.

As with many other aspects of Solvency II that need revisiting, there are numerous solutions each of which warrant individual assessment before a single recommendation can be made. This is a role for more specialist working parties than our own. Indeed there are already working parties that have looked at, or are looking at, MAs and Transitional Measures for Technical Provisions.

1.5. Impact on Behaviour

Solvency II generally rewards the matching of assets and liabilities through a reduction in Solvency Capital Requirement (SCR), although there are exceptions, the most notable of which is the risk margin. This encourages insurers to assess which risks are rewarded and which are not. In turn this has an impact on behaviour, which we cover in section 4.

In the United Kingdom such a practice has been prevalent within with-profits funds since the realistic balance sheet was introduced in 2003. By contrast, e.g. for German insurers, there is a trend to extend the duration of their assets so as to reduce the interest rate risk. In practice, the trend in Germany has been gradual because of the transitional arrangements, the Ultimate Forward Rate (UFR) to some extent and the fact that the interest rate down shock in determining the SCR is small when rates are low.

For annuity business the MA eligibility rules have introduced a shift away from assets such as callable bonds to illiquid assets. To meet these rules, some previously favoured illiquid assets, such as equity release mortgages, have had to be securitised internally.

Even for unit-linked business moving away from matching the face value of units to one that is closer to the best estimate liability (BEL) reduces capital requirements.

One of the impacts of Solvency II though that raises some concern is that it increases pro-cyclicality. As markets fall or become more volatile insurers either have to find more capital or sell. There is a good argument for counter-cyclical buffers to dampen such effects and provide time for insurers to take a more considered response to changing market conditions.

Finally, there is also the impact on product design. A combination of capital requirements and low interest rates will increase the trend (already evident in the United Kingdom) away from traditional savings products with guarantees to unit-linked contracts.

Insurers that sell both savings and protection business can benefit from the diversification benefits of holding both insurance and market risk on their balance sheet.

1.6. Pillars 2 and 3: Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (ORSA), Liquidity and Disclosures

Most of the contentious issues have been around Pillar 1 and long-term guaranteed business. Solvency II though is also about embedding risk management and good governance within the Boards of insurance companies and clearly defining where their responsibility lies. We cover these aspects in section 5.

In this regard, much of Solvency II has the UK’s DNA throughout it. Pillar 2 aspects such as ORSA are similar to the Individual Capital Assessment (ICA) regime we knew before Solvency II. However, Pillar 2 has raised the bar considerably compared to the Solvency I regime.

Our view, and that of those voting at the Life Conference, was that Pillar 2 has been a major success of Solvency II adding to financial stability.

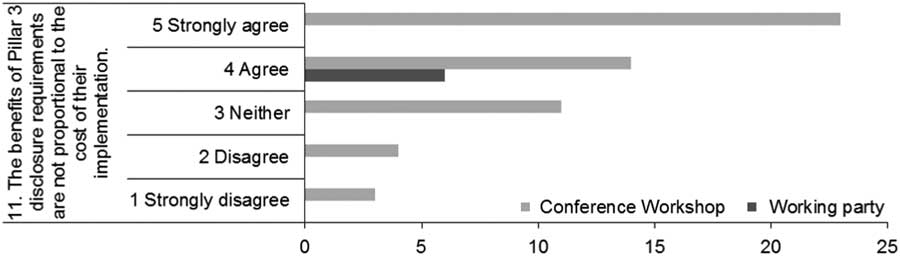

Pillar 3 has introduced greater transparency across Europe in terms of reporting and greater public disclosure. From a UK perspective though, there is a loss of some of the granularity of detail that we are used to seeing in the outgoing PRA returns. In that respect there is less transparency.

In the working party’s opinion, certain parts of the detailed reporting do not appear to justify the costs. The whole process of looking through to the layering of assets within funds requires huge amounts of processing with its associated costs and resourcing, without it being clear how the information benefits regulators or analysts.

1.7. Solvency II’s Performance Relative to its Objectives

Pulling together those aspects of Solvency II that the working party explored we have drawn our own conclusions as to how well Solvency II performed relative to its objectives of improved consumer protection, effective risk management, harmonisation and financial stability.

1.7.1. Improved protection of policyholders and beneficiaries

As we have discussed, the introduction of a market consistent approach has resulted in a regime that provides a more scientific approach of determining capital requirements. In addition, allocating more money to back insurance liabilities and their capital requirements has also enhanced policyholder protection.

During the oral evidence given by Andrew Chamberlain on behalf of the IFoA, the TSC made the point that, because the PRA has no primary responsibility in respect of competition, allocating more money to back insurance liabilities and their capital requirements is an easy way for regulators to improve policyholder protection.

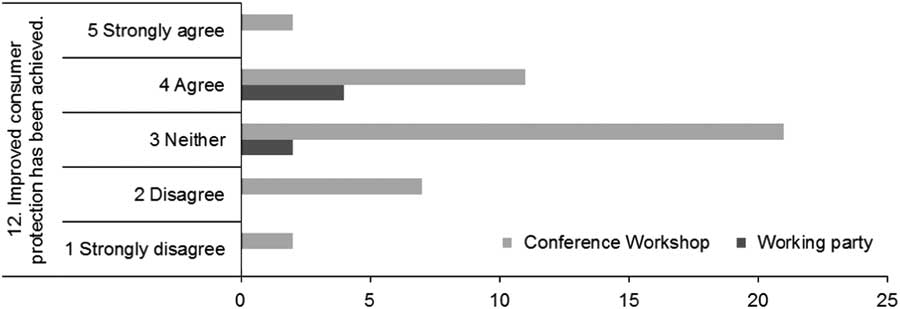

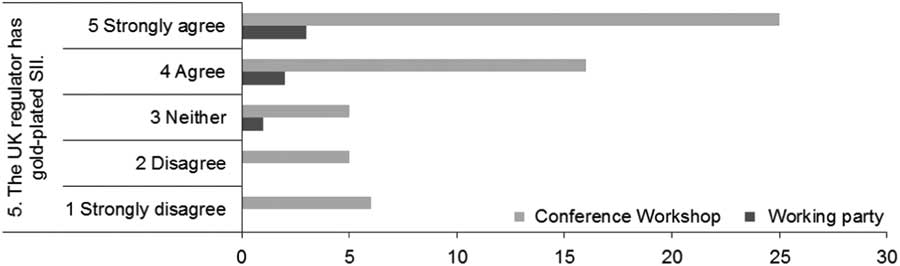

In our working party we believe that the improved consumer protection objectives have been met although there was no prevailing view to that effect at the Life Conference workshop (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Improved customer protection has been achieved. Conference workshop: Votes 43, average 3.1, SD 0.9.

1.7.2. Effective risk management

The market consistent aspect of Solvency II provides a solid foundation upon which the capital requirements reflect the risks inherent within an insurance company or group.

Insurers are now rewarded for matching liabilities with corresponding assets where this is possible. Market consistency is being questioned in terms of its impact on financial stability and its relevance to long-term guaranteed business. However, it has a huge impact in encouraging effective risk management.

These incentives have been reduced by the extrapolation from a 20-year point to the UFR in respect of euro liabilities. Similarly, under the MA it is possible to improve a life insurer’s capital position by taking on credit risk. To ensure effective risk management it has been necessary to develop strict admissibility and cash flow matching rules.

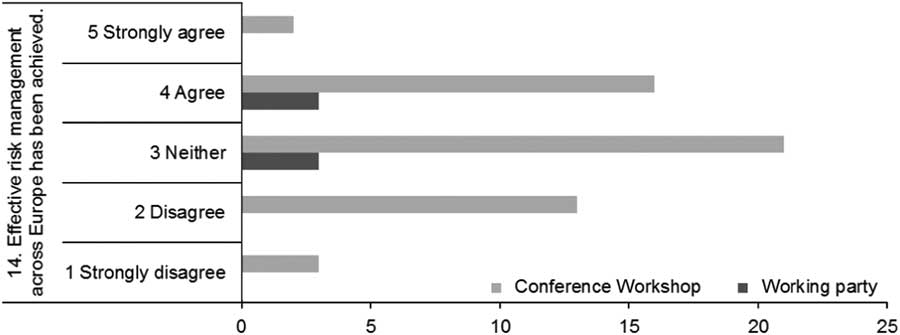

Our working party’s view is that in general Solvency II has delivered a system that tends to encourage effective risk management. The views of those voting at the Life Conference was less emphatic where there were divergent views on how successful Solvency II has performed in this respect (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Effective risk management across Europe has been achieved. Conference workshop: Votes 55, average 3.0, SD 0.95.

1.7.3. Harmonisation

The detail of the regulation and the introduction of a common European regulator has resulted in a high degree of harmonisation on the face of it, but in section 6 we take a deeper look to reveal important areas in which harmonisation has not been achieved. Even reserving and capital requirements may differ significantly between insurers.

An insurer writing long-term traditional with-profits business in euro benefits from an extrapolation of the euro swap curve to the UFR from year 20. Whilst a UK insurer writing annuity business may, or may not, take advantage of the MA.

Nor, in this case, is the reporting similar. The impact of the MA is disclosed when reporting whilst the impact of the extrapolation to the UFR is not. Hence an analyst has additional information to form a view on the balance sheet strength of a UK annuity writer but does not necessarily have similar information regarding a continental with-profits office.

An insurer with an internal model might measure more risks than an insurer using the standard formula. Elsewhere aspects such as the volatility adjustment (VA) and the transitional measures are not applied uniformly.

That said, Solvency II has imposed a sophisticated, detailed and revolutionary set of rules across 28-member states and this feat is a major accomplishment.

Despite this, our view and that of our voting audience at the Life Conference was that Solvency II had failed to achieve harmonisation (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Harmonisation across Europe has been achieved. Conference workshop: Votes 54, average 2.0, SD 0.85.

1.7.4. Financial stability

There is a concern around the pro-cyclical nature of market consistent approaches and questions are being asked about the going concern approach of Solvency II compared to the run-off approach of Solvency I.

Pro-cyclicality and financial stability are areas where we can inform the debate. Market consistency will tend to be pro-cyclical. If markets fall, it makes sense to hold capital against further falls. For insurers without enough spare capital this can result in insurers selling risky assets creating pro-cyclicality with potentially disastrous outcomes for financial institutions. The move to market consistency and the use of a 1-year Value at Risk (VaR) increases the risk of herd behaviour as, in the absence of capital, insurers would be required to de-risk within the same time frame as other institutions.

Markets though can over-react. Many are not deep and liquid. Insurers writing long tail business do not have immediate cash flows to pay. A capital regime that provides time for insurers to formulate a measured response would be desirable.

The symmetric adjustment for equities in the Standard Formula achieves this but its effectiveness is restricted by a maximum 10% reduction in the size of the standard equity stress.

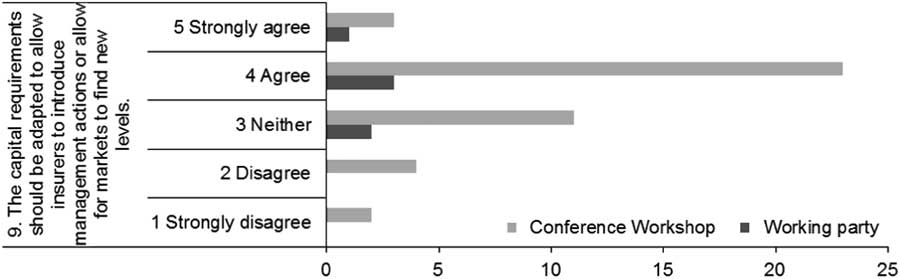

It does, however, give time for markets to find their new level if they have over-reacted and for insurers to formulate their best response if they have not. Variations to this and applying it to other market risks such as spread risk could be one solution. Indeed there is a range of solutions that could be usefully assessed.

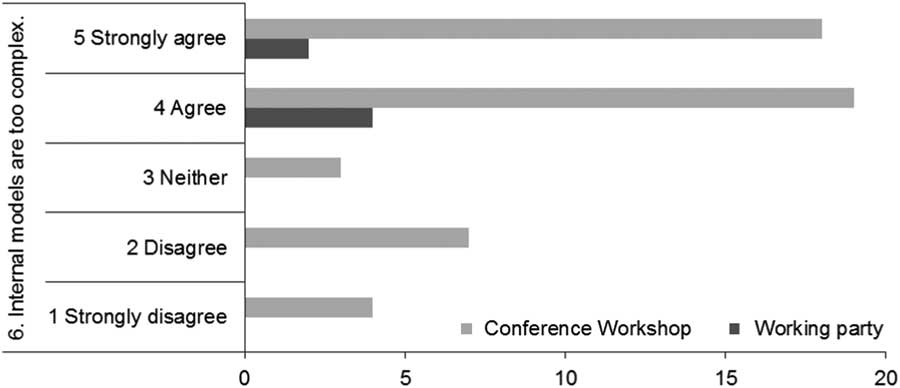

The concern around pro-cyclicality is such that our working party is unanimous in its view that Solvency II has fallen short of its goal of aiding financial stability. The Life Conference voting pattern was similarly tight but with a stronger view that Solvency II had not met its objectives (see Figure 4).

Figure 4 Financial markets are more stable. Conference workshop: Votes 56, average 1.4, SD 0.55.

1.8. Impact of Brexit

Brexit could not be ignored and section 7 covers this. The working party feel that the United Kingdom should retain Solvency II as a framework but take advantage of our ability to adapt it to meet our needs. Without the need to reach agreement with 27 other member states the United Kingdom has greater scope to adapt Solvency II to address its shortcomings.

It is also worth bearing in mind that if the United Kingdom chooses to retain Solvency II then, with no voice, Solvency II could evolve in a way that does not suit the United Kingdom. As an example there is no great attachment to the MA in mainland Europe and the risk is that it could be removed. We should aim to avoid being locked into Solvency II where we have no say and where changes could go against the United Kingdom.

Passporting and equivalence through mutual recognition of the UK’s and EU’s regulatory system is a highly desirable goal. This is especially true for international nature of business carried out by Lloyds of London and in the London Market. For multi-national life companies it is perhaps less important given that the current norm is to operate through local legal entities.

If we change too much, passporting and equivalence could be at risk but it ought to be noted that these decisions are made at a political level. The United States of America enjoys equivalence (but not passporting) even with significant differences between our two regimes. As we have already noted harmonisation has not been achieved in respect of a German insurer writing long term with-profits business compared with that of a UK annuity writer.

The EIOPA review for Europe as a whole and Brexit for the United Kingdom may permit streamlining and simplifying of systems and processes that could make our industry more flexible and potentially more competitive. It is hoped that this paper and the transcripts of the discussion will help inform that debate.

1.9. Closing Comments

As EIOPA and the TSC review Solvency II and look to the future evolution of the regime, the working party hopes that this paper will represent a good overview of the effectiveness of Solvency II. We have been pleased to input into the IFoA’s response to the TSC consultation. We also hope that this paper, along with the discussion, will represent an enduring retrospective on the initial introduction of Solvency II and the lessons that can be learned from it. There are a number of areas where more research could be conducted – the issues around discounting, the merits of the various alternatives to the calculation of the risk margin, the implications of counter-cyclical buffers for a range of market risks. We look forward to the profession continuing to make a contribution in areas such as these.

2. Market Consistent Valuation

2.1. Market Consistency

A market consistent value is often associated with fair value and should be rational and unbiased. Kemp (Reference Kemp2009) defines the market consistent value of an asset or liability to mean:

-

a) its market value, if it is readily traded on a market at the point in time that the valuation is struck; or

-

b) a reasoned best estimate of what its market value would have been had such a market then existed, in all other situations.

Market consistent valuation frameworks rely on financial instruments traded in deep and liquid markets where cash flows can be used to create a replicating portfolio, or market observables can be used as inputs to models.

Solvency II started with the intention of being market consistent. However, throughout the implementation process numerous compromises have been made, and with each compromise it moves a little further away from true market consistency. Some deviations were more justifiable than others as it has been argued that “full” market consistency may be too harsh or not suitable for long-term liabilities. However “partial” market consistency impacts the potential to hedge liabilities. While some of the measures have more theoretical justification, others have been political compromises amongst EU members to ensure the sustainability of long-term business in certain markets.

Another view is that over and above the theoretical benefits of market consistency, Solvency II also wishes to harmonise valuation methodologies across the EU with minimal scope for subjectivity. A market consistent valuation framework is one way to achieve this. In effect, deviations discussed in this section relating to market consistency may also be moves away from harmonisation.

The main areas of concern are the UFR, MA, VA and transitional measures. These all formed a part of the long-term guarantees (LTG) package, with the aim to eliminate “artificial” volatility from the balance sheet of insurers, but also moves Solvency II away from “full” market consistency. In this section, we will discuss the UFR, MA and VA as these are focussed on short-term market fluctuations; in addition, topics such as the extended recoverability period and symmetric adjustment will be touched upon but not explored in detail here.

The transitional measures described in section 2.3 are also a significant deviation from market consistency as they smooth the transition between Solvency I and Solvency II reserves on the in-force business of insurers without taking the full impact of Solvency II from the implementation date.

2.1.1. UFR

The risk-free yield curve is based on interest rates swaps observed in deep, liquid and transparent markets; where swaps are not available government bonds are used. However, for long-term liabilities where liquid financial instruments are not available, the curve is extrapolated from a stipulated Last Liquid Point (LLP) to the UFR, which is provided by EIOPA.

For the euro the LLP is year 20 and the extrapolated curve converges to the UFR of 4.2% over a period of 40 years. Anecdotally the 20 year LLP seems to be a political compromise between the European countries. However, in the current low interest rate environment EIOPA has already suggested a lower UFR in just over 1 year into Solvency II. Their suggestion is that, for the euro in 2018, the “calculated UFR” is 3.65% (as opposed to the current 4.2%) and that after applying a maximum year on year change of 15 basis points the “applicable UFR” will be 4.05% (EIOPA, 2017)

With interest rates at unprecedented low levels, many question the suitability of the UFR. There are debates around this area with insurers and regulators alike trying to gauge what the “right” value should be.

The emergence of negative interest rates in countries such as Switzerland and Germany show more acutely the issues surrounding a fixed UFR set before the current low interest rate environment. In general, negative interest rates challenge current economic theory and the calibration of solvency models across a broad spectrum of financial institutions.

Some countries, such as Germany, are more dependent on the value of the UFR than others, due to the nature of the business sold; while other countries, such as the United Kingdom, rely on measures such as the MA. These valuation tools are a part of the LTG package, countries which may object to the UFR but rely on other aspects of the LTG package, are less likely to challenge it.

The UFR is less of an issue in countries where swap markets are deemed to be deep and liquid out to very long maturities.

2.1.2. MA

The MA is a flat addition to the risk-free yield curve, and can be applied to portfolios where the liabilities are fixed cash flows and the assets backing them can be separately identified, organised and managed from the rest of the business activities of the insurer.

MA is based on the portfolio of the insurer, and is essentially a proxy for the illiquidity premium on the assets held to back the liabilities.

As at 1 January 2016, according to data published by EIOPA (2016a), the MA was being used by insurers in Spain (15 insurers) and the UK (23 insurers) with two further national supervisors indicating that it may be used in the future, particularly in respect of new business. The data shows that removing the MA would reduce the SCR ratio by an average of 65% in the United Kingdom and 50% in Spain.

In the United Kingdom it is applied to annuities, however, it might be considered unfair to single out annuities for preferential treatment. That it is restricted to annuities reflects the fact that this was part of the compromise measures agreed as part of Omnibus II.

Basing the value of a fixed cash flow liability on the assets backing it and recognising on day 1 the unearned illiquidity premium is clearly not market consistent. Indeed it is very similar to the Solvency I discount rate used in the United Kingdom but without a prudent margin in the fundamental spread.

This impact can be to reduce the technical provisions at an undertaking level by up to circa 10%, compared to not using the MA, according to data published by EIOPA (2016a).

Investing in this way creates a capital requirement for spread risk although the spread risk has been reduced to capture the fact that the portfolio is exposed to default rather than spread risk. According to data published by EIOPA (2016a), the impact at insurer level can be to reduce the SCR up to a half, although for other insurers it can result in a small increase.

It is possible that this capital requirement can be more than covered by the benefit of the lower BEL coming from the higher discount rate. This appears counter-intuitive as it is the exact opposite of rewarding effective risk management, as it is hard to imagine that the additional yield comes without additional risk other than illiquidity risk.

There are stipulations in the derivation of the fundamental spread on government and non-government exposures; it is also adjusted so that the MA on non-investment grade assets does not exceed that calculated for investment grade assets. Hence additional capital is required when a BBB-rated bond downgrades to BB-rated.

The MA can become negative when spreads are very tight, although it is usually higher than the VA.

The eligibility criteria for the MA are set out in Appendix 5.

In order to use the MA, insurers need to apply for it from their national regulator; however, once approved the insurer cannot choose not to apply it. If the insurer cannot comply with the eligibility criteria or is not able to restore eligibility status, it will be banned from using MA for a period of 2 years. These rules appear to be a deterrent from applying the MA in the first place and also introduce a new risk in respect of the loss of the MA. It is not clear what other benefit this rule serves for the protection of policyholders.

The consequence of a departure from a market consistent framework is the ability to arbitrage rule inconsistencies.

Assets such as equity release mortgages do not meet the rules and can no longer be held directly within MA portfolios. However, many companies have created special legal entities to meet the eligibility criteria. Special purpose vehicles (SPVs) have been used for cash flows from equity release products, commercial real estate mortgages and infrastructure finance (Rule, Reference Rule2017). In these SPVs securitisation techniques such as credit enhancement features and liquidity facilities are used so as to allow them to issue eligible senior tranches.

Liabilities such as Periodic Payment Order (PPO) annuity payments can, at least in theory, be reinsured on a Retail Price Index basis into a MA compliant portfolio as a means to derive some benefit from the MA.

Arbitrage opportunities such as this have created the growth of an “industry” in structuring portfolios to make them eligible. These increase the cost base of insurers, increase operational risk and add to the complexity of an insurer’s balance sheet.

Finally, the SCR is calculated separately for different MA portfolios and cannot be diversified with the rest of the insurer’s business activities, or between MA portfolios. Therefore, the more MA portfolios, the less diversification benefit that can be taken into account. However, MA can be taken into account for the calculation of the SCR for spread risk, and hence can decrease the SCR. It significantly reduces SCR volatility too.

2.1.3. VA

The VA is a constant addition to the liquid part of the risk-free yield curve, therefore the spread is only applied up until the LLP for each currency and thereafter the adjusted yield curve is extrapolated to the UFR should it also be applicable.

It aims to protect insurers with long-term liabilities from short-term volatility in the market. VA is the spread between the interest rate of the assets in the reference portfolio and the corresponding risk-free rate for each currency, minus the fundamental spread – a haircut for default and downgrade on the qualifying assets. If the market spreads are very wide in a specific country, a country spread can be added to the currency spread.

The reference portfolio is determined by EIOPA and includes assets typically held by insurers to cover their liabilities (BEL).

Unlike MA, VA can be used in conjunction with transitional measures on risk-free rates, and if the VA is used MA cannot be applied. However, in the standard formula it does not respond to SCR shocks for spread risk.

The use of VA should be allowed by national supervisors, but some countries may have an approval process.

As at 1 January 2016, according to data published by EIOPA (2016a), VA was being used by 852 undertakings in 23 countries, the largest take-ups are in France with 217 undertakings. The technical provisions of the French undertakings applying the VA represent 18.1% of the total technical provisions in the European Economic Area (EEA); this is followed by Germany at 10.1% and the United Kingdom at 9.2% and are mainly for the life businesses.

The data show that removing the VA would reduce the SCR ratio by an average of 34% at the EEA level, with the biggest impact in Denmark and Germany at 91% and 85%, respectively; as compared to the United Kingdom where it is only 6%, therefore at the EEA level it is fairly significant especially for certain countries such as Germany.

2.1.4. General

MA and VA are utilised by different insurers in different countries. Where approvals need to be obtained, processes may not be equally stringent therefore creating an uneven playing field. This reduces the harmonising effects of Solvency II, which is one of the objectives mentioned in section 1.2.

The various adjustments to the risk-free discount rate raise the question of whether it is too conservative for the insurance industry with long-term liabilities. Where specific adjustments were designed for specific products, such as the MA, there could be a case for unification by establishing a fairer adjustment across the whole yield curve and across all products.

This suggests that there is a case, if not for entity specific discount rates, then a discount rate that reflects a good investment grade entity where insolvency can be entertained – AA or A rated discount curves.

The fact that the standard formula treats sovereign bonds in the domestic currency in all member states as risk-free (as stated in section 3.1.6.6) raises questions as not all countries issue bonds of equal credit quality; spreads in certain countries trade at significant spreads above German government bonds. Further, certain supranational, regional and local authority bonds get a similar treatment, irrespective of financial health although there are requirements they need to meet, e.g., around tax raising powers to provide consistency with sovereigns (Solvency II Wire, 2016a).

Solvency II equivalence for other non-Solvency II countries, e.g.: the United States, Bermuda and Japan also introduce non-market consistent valuation methodologies and reduce the impact of harmonisation for insurers across countries outside of the EU. There is already emergence of evidence which show insurers in Solvency II countries reinsuring longevity risk to regions outside of the EU where solvency requirements are not as stringent (Bulley, Reference Bulley2016).

2.1.5. Findings on market consistency

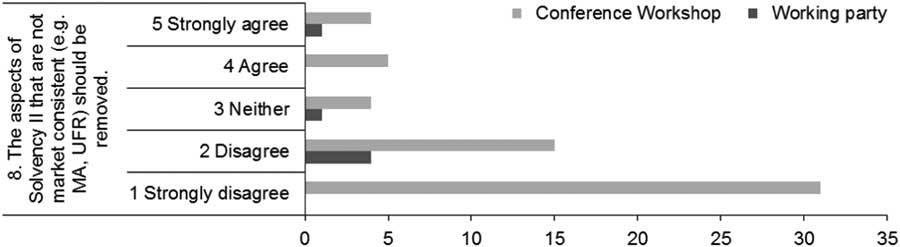

Our survey at last year’s Life Conference in Edinburgh asked whether aspects of Solvency II that were not market consistent should be removed.

Figure 5 shows that most participants were in favour of the deviations from market consistency, and within the working party we have a difference of opinion on the subject.

Figure 5 The aspects of Solvency II that are not market consistent (e.g. matching adjustment (MA), Ultimate Forward Rate (UFR)) should be removed. Conference workshop: Votes 59, average 1.9, SD 1.25.

There may be flaws in following a market consistent approach but in the working party’s view it is through market consistency that effective risk management is rewarded.

In the United Kingdom, annuity business is the most important long-term guaranteed business written, and it has been recognised that default risk rather than spread risk was key and this was accommodated through a higher discount rate linked to the assets’ owned and lower capital requirements.

The front-ending of the illiquidity premium on the assets held by the insurer is a deviation from market consistency, which means that a significant proportion of the UK’s long-term guaranteed business is still regulated on a basis that is close to the Solvency I regime. To ensure effective risk management for MA business it has been necessary to develop strict admissibility and cash flow matching rules, which comes with issues of its own in terms of creating additional costs and complexity.

Further, the impact of market consistency on financial stability has come into question and the effect on long-term guaranteed business. However, overall, it has made significant improvements in encouraging effective risk management in Europe.

2.2. Risk Margin

2.2.1. Cost of capital approach

Under Solvency II, the technical provisions are defined as the sum of the BEL and risk margin.

The risk margin is intended to represent the amount another insurer would require to take on the obligations of the insurer. It is calculated using a cost of capital approach; the insurer must project its SCR in respect of non-hedgeable risks, and apply a prescribed cost of capital charge of 6% p.a. This charge is then discounted at the risk-free rate to determine the risk margin.

The risk margin is relatively large for insurers with significant non-hedgeable risks, and particularly for those that have a long duration, such as longevity.

The underlying concept is that the notional transfer of technical provisions to another insurer would enable that insurer to cover the technical provisions (including the risk margin) and that the run-off of risk margin each year would compensate the insurer for providing capital against non-hedgeable risks. This effectively means that the transfer of technical provisions of an insurer in financial difficulties would be sufficient (on best estimate assumptions) to fully capitalise the transferred liabilities in the future.

2.2.2. Choice of approach: risk margin as prudence

The concept of a risk margin was not an entirely new concept unique to Solvency II.

The Market Consistent Embedded Value Principles (CFO Forum, 2016a), which pre-date Solvency II, include Cost of Non-Hedgeable Risks, which is similar in concept to the Solvency II risk margin, and is presented as an equivalent cost of capital.

When Solvency II was under development, two alternative approaches to defining the risk margin were considered (CEIOPS, 2007, page 12). One was the cost of capital approach described above (which is the Swiss Solvency Test (SST) approach), and the other was a recalculation of liabilities replacing best estimate assumptions (which are by definition 50th percentile) with an alternative point on the probability distribution, e.g., 75th percentile (which is the Australian approach). One of the main factors which swayed the decision in favour of cost of capital is the difficulty of defining assumptions on the basis of a probability distribution.

It appears from the consideration of two alternative approaches that a key driver for the inclusion of the risk margin in Solvency II was the desire to retain some form of prudent margin to the BEL, rather than a specific conviction that cost of capital must be covered.

2.2.3. Projection of SCR

Although the cost of capital approach was selected on grounds of relative simplicity, it requires an annual projection of SCR for the full run-off period of the liabilities, which is anything but straightforward for many insurers.

To calculate SCR accurately at each future duration requires complex projections within complex projections, and this is impractical for many insurers’ models. This difficulty is recognised within EIOPA guidance, which has set out a number of simplified methods. Unfortunately, these methods do not appear to be sufficiently accurate in many cases.

One robust approach to this problem is to define, for each block of business and for each component of SCR, an appropriate “risk driver” which is output by the model, so that it is assumed that that component of SCR moves proportionately to the driver. For example, for the mass lapse component, the risk driver might be the excess of total surrender values over total BEL in each future year. The projected SCR is then determined in each future year by combining the individual elements in the normal way. This approach requires both analysis and understanding of causes of risks and significant testing.

2.2.4. Cost of capital rate

The cost of capital rate of risk free plus 6% p.a. is defined in the European Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/35, which is the same rate used for the corresponding calculation in the SST.

It was defined on the basis that the insurer to which liabilities are notionally transferred is itself subject to risks and therefore subject to a relatively high cost of capital. In the development of the SST, it was stated that 6% was deemed to be a reasonable estimate for the stressed cost of capital in BBB-rated companies, which broadly corresponds to the definition of the capital requirement in the SST (Federal Office of Private Insurance, 2006).

It may also be relevant to consider whether discounting at the risk-free rate in determining the risk margin is consistent with adopting a high cost of capital rate reflecting risk.

2.2.5. Problems with the risk margin

In practice, the risk margin has been subject to considerable criticism, primarily on the grounds that it is too sensitive to interest rate movements, but also that it is in any case too large.

To illustrate this, in a speech on 21 February 2017, David Rule (Executive Director, Insurance Supervision, Bank of England) stated that total risk margins for major life insurers in the United Kingdom had increased from £30bn at the start of 2016 to about £44bn in September 2016. He also estimated that a 100 bp reduction in interest rates increase risk margins by around 20%. He went on to refer to the “flawed design” of the risk margin, though he pointed out that for existing business the problems are mitigated by the transitional measure on technical provisions (Rule, Reference Rule2017).

The other issue with the risk margin is that its sensitivity to market risk does not fall within the calculation of the SCR under the standard formula. Consequently hedging the risk margins sensitivity to interest rates results in an increase in the SCR for rates risk.

2.2.6. Potential amendments to the risk margin

An urgent review of the operation of the risk margin is needed.

This could start off by considering two fundamental questions:

-

∙ Is the purpose of the risk margin to provide coverage for the cost of capital, or is it more a means of standardising a measure of prudence in addition to BEL?

-

∙ If the former (or if cost of capital is the preferred approach to the latter), is the requirement to cover full future capitalisation of existing business an appropriate element of Solvency II, or does this represent too high (and therefore too expensive) a level of customer protection?

Answers to these questions could then illuminate a review of risk margin.

The following changes could be considered:

2.2.6.1. Changes within the existing overall structure

-

∙ Reduce the cost of capital rate from 6% p.a.

-

∙ Align the cost of capital rate more specifically to the insurance sector.

-

∙ Increase the discount rate used to determine the risk margin.

-

∙ Make the risk margin more responsive.

-

∙ For example, use a mechanism to adjust the discount rate similar to the MA or VA.

-

∙ Use a cost of capital that decreases as the risk-free rate decreases, though the theoretical justification for this is not clear.

-

-

∙ Treat longevity risk as hedgeable – justified by the increasing availability of reinsurance

-

∙ Alternatively, allow insurers to use the market price of longevity hedging when lower than the risk margin.

-

-

∙ Determine the cost of capital not on the basis of the projected SCR, but of the excess of the projected SCR over the projected risk margin

-

∙ This would be consistent with the assumption that there would be no risk margin after the transfer of liabilities, i.e., that full capitalisation was not needed.

-

∙ However, it would introduce circularity into the calculation of the risk margin, requiring an appropriate solution.

-

-

∙ Allow SCR calculations to take into account the change in risk margin under the scenario:

-

∙ This would mitigate the impact of the risk margin by reducing the amount of SCR, which would itself reduce the risk margin further.

-

∙ However, it would introduce circularity into the calculation of the risk margin, requiring an appropriate solution.

-

-

∙ Impose an artificial maximum to risk margin

-

∙ For example, a defined percentage of SCR at the current date, similar to the definition of the minimum capital requirement (MCR).

-

2.2.6.2. More extensive changes

-

∙ Replace risk margin with something completely different

-

∙ If it is considered that the risk margin is primarily a prudent addition to BEL, this could be relatively simple, e.g., a defined percentage of the SCR (or MCR).

-

-

∙ Abolish the risk margin altogether.

The possibilities listed above might be considered suitable for consideration by the EU, or alternatively by the UK post-Brexit.

2.3. Transitional Measures

2.3.1. Background and summary

-

Transitional measures are set out in Articles 308b-308e of the Solvency II Directive. These include:

-

∙ Transitional measure on risk-free interest rates (Article 308c).

-

∙ Transitional measure on technical provisions (Article 308d).

-

∙ Equity stress in standard formula (Article 308b, paragraph 13).

-

∙ Grandfathering of Tier 1 and 2 Own Funds (Article 308b, paragraphs 9 and 10).

-

∙ Concentration and spread risk for government exposures not denominated in the domestic currency (Article 308b, paragraph 12).

-

∙ Extension of period for initial compliance with SCR (Article 308b, paragraph 14).

These transitional measures are presented as providing an orderly transition to Solvency II.

They are a package of measures negotiated as a political response to issues which were hindering final agreement to implement Solvency II. It would not have been politically acceptable to introduce Solvency II in many countries, including the United Kingdom, if that had meant that many insurers suddenly could not meet the Solvency II requirements.

The most significant issue was the cost of LTG in a low interest environment, and the measures sit alongside the other changes introduced in response to this issue. However, other issues are also covered by the transitional measures.

2.3.2. Transitional measures on risk-free interest rates and technical provisions

These two measures are alternatives – an insurer can use one or the other, but not both together.

Both measures apply only to business in force at end-2015.

Both measures require regulatory approval. The Bank of England has indicated that UK insurers wishing to use transitional measures will be given the freedom to do so (Woods, Reference Woods2015). In contrast, the regulator in the Netherlands has stated that approval will not normally be given, on the grounds that it would be a backwards step from the existing solvency regime there (McCaughey, Reference McCaughey2016).

The results ignoring the measures must still be produced and published. It is therefore possible that rating agencies and other commentators will place more weight on the results ignoring the transitional measure, which better reflect a level playing field. However, in the United Kingdom, analysts appear to be concentrating on results including the transitional measure, as use of transitional measures does not restrict payment of dividends.

The Directive requires that an insurer that would be insolvent without the transitional measure must report annually to the regulator on progress to restore solvency by the end of the transitional period.

2.3.2.1. Transitional measure on risk-free interest rates

This is an adjustment to the Solvency II risk-free rates, equal to a proportion of the difference between the Solvency I interest rate and the single interest rate equivalent to the Solvency II risk-free interest rates, determined as at end-2015 (allowing for the VA where relevant).

The proportion starts at 100% and is reduced to zero linearly over 16 years.

In countries that used a passive Solvency I valuation method, the measure will initially result in a discount rate broadly equivalent to the Solvency I rate, which may be significantly higher than the Solvency II risk-free rates.

According to data published by EIOPA (2016a), five insurers in four countries were applying this transitional measure on the basis of the Solvency II opening balance sheet or quarterly reporting at 31 March 2016. None of these insurers were in the United Kingdom.

2.3.2.2. Transitional measure on technical provisions

This is an adjustment to technical provisions, equal to a proportion of the difference between the Solvency I and Solvency II technical provisions, determined as at end-2015 (allowing for the VA where relevant). The adjustment may be applied at risk group level.

The proportion starts at 100% and is reduced to zero linearly over 16 years.

The Solvency II technical provisions include the risk margin, so this measure effectively defers the introduction of the risk margin, and it will therefore mitigate the sensitivity of the risk margin to interest rates in the short term.

In the United Kingdom, the base position for this measure is normally the technical provisions in the ICA, so the initial adjustment is likely to mainly comprise the risk margin together with the impact of restrictions to contract boundaries, as the remaining technical provisions are similar between ICA and Solvency II.

In countries that used a passive Solvency I valuation method, the adjustment will also include significant elements relating to differences in the discount rate and other valuation assumptions.

The amount of the adjustment is initially defined in monetary terms, there is therefore the likelihood that it will cease to be appropriate; in particular it could become too large following a rise in interest rates or too small following a fall.

There is therefore a provision that the regulator may require (or approve a request from the insurer for) a recalculation every 24 months or where the risk profile of the insurer has materially changed. The PRA has stated that it expects a recalculation every 24 months, and has listed a number of changes in risk profile that would be regarded as material, including changes in interest rates, specifically a change of at least 50 bps in the 10-year yield.

Although this transitional measure can act as a hedge to changes in the risk margin, the review process used by the PRA appears complicated and time-consuming, reducing the effectiveness of the hedge against volatility in the short term. A simpler and more wide-ranging process for recalculation would be welcome.

According to data published by EIOPA (2016a), 154 insurers in 12 countries were applying this traditional measure on the basis of the Solvency II opening balance sheet and quarterly reporting at 31 March 2016, of which 140 are life or composite insurers, with 28 insurers in the United Kingdom. These insurers represent 24% of total EEA technical provisions; the corresponding proportion in the United Kingdom is 57%.

On the basis of insurers which completed the EIOPA stress tests in 2016 (representing about 75% of each national market share, measured by technical provisions), the average SCR coverage ratio at 1 January 2016 for insurers in the EEA using this measure was 183% including the measure and 115% without it. The corresponding ratios in the United Kingdom were 143% and 105%. Despite the low average ratio ignoring this measure, EIOPA reported that no UK insurers would fail to cover their SCR without the measure. Nevertheless, it can be seen that this measure is very significant to solvency.

2.3.2.3. Comparison between measures

As the technical provisions transitional measure includes the risk margin, this measure is likely to be financially more advantageous than the risk-free interest rates transitional measure for most insurers. However, in countries using a passive Solvency I valuation method, it is possible that the risk-free interest rates measure could be more advantageous for a few insurers, e.g., where the impact on technical provisions of moving to risk-free discount rates is offset by changes to other assumptions.

This analysis is borne out by the statistics in EIOPA (2016a), with 154 insurers using the technical provisions measure compared with just five using the risk-free interest rates measure. In the United Kingdom, the impact of the technical provisions measure is normally very significant, whilst the risk-free interest rates measure would not normally be significant and cannot be used in conjunction with the MA. It is therefore not surprising that 28 UK insurers were using the technical provisions measure, with none at all using the alternative.

Both measures require technical provisions to be determined and reported on two different bases. This requirement may be particularly onerous where recalculation of the technical provisions adjustment is needed or where legacy systems must be maintained.

An added complication for the technical provisions measure may be increased volatility of results between recalculations, as well as uncertainty over whether a change in risk profile is sufficiently material to trigger the regulator to require recalculation or to permit approval of a request from the insurer. Some insurers report the impact of a notional recalculation of the measure.

2.3.3. Comments on selected other transitional measures

2.3.3.1. Equity stress in standard formula

This permits the equity stress required in the standard formula for equities purchased before 2016 to be scaled linearly over 7 years from 22% to the full standard formula stresses (39% for type 1 equities and 49% for type 2 equities, in each case subject to the symmetric adjustment).

This measure is optional, and does not require regulatory approval.

The intention is to mitigate the need for forced sales of equities resulting from the introduction of the risk-based capital requirements within Solvency II.

Insurers using this measure are required to keep detailed records of equities subject to the measure. Approximate methods are permitted in the case of equities held within collective investment schemes.

A potential disadvantage is that the symmetric adjustment is not included in the initial revised stress, so, although solvency ratios are higher with this measure, they are likely to be more volatile in times of equity price movements.

2.3.3.2. Grandfathering of existing capital

This measure includes capital to be treated as Tier 1 or Tier 2 that would not otherwise qualify as such, provided that it was issued before 18 January 2015 and that it met the relevant conditions under Solvency I.

This treatment is permitted for 10 years from 1 January 2016.

This appears to be a sensible provision, although it may have provided a short opportunity to issue capital to take advantage of the concession.

2.3.3.3. Concentration and spread risk in standard formula for government exposures not denominated in the domestic currency

This measure requires parameters in the standard formula in respect of EEA government exposures denominated in the currency of another EEA state to be reduced to zero in the first 2 years, and then increased to the full level over the next 2 years.

This presumably is mostly relevant to euro-denominated securities issued by non-Eurozone but EU governments and vice versa (e.g. issuance by Eurozone supranationals such as EIB in sterling).

It is unlikely to be significant to many insurers, though its inclusion in the package indicates that it is significant in some cases.

3. Capital Requirements

3.1. Standard Formula

The standard formula is used to determine the SCR for insurers which do not have an approved internal model. It is therefore considered to be particularly suitable for smaller and medium-sized insurers which are not subject to specific or unusual risks.

The standard formula is of great significance, as it is used by the vast majority of insurers subject to Solvency II. Table 1, published by EIOPA (2016a) based on the entire EEA market as at 1 January 2016, demonstrates this.

Table 1 Number of Undertakings Split by Type and Method of Solvency Capital Requirement Calculation

Although it is considered suitable for smaller and medium-sized insurers, it is believed that outside the United Kingdom the standard formula is used by many larger insurers.

3.1.1. Summary of general structure of standard formula

The standard formula requires a separate capital requirement to be determined for each individual risk type (up to 17 for life insurers).

The capital requirement for each risk is defined in the Delegated Regulation, and for life insurers it is equal to the impact on Own Funds (ignoring the risk margin) of specified scenarios or other calculations of the following types:

-

∙ For interest rate risks, the more onerous of two yield curve scenarios (up and down).

-

∙ For other market risks, scenarios with changes in the market value of each type of exposure.

-

∙ For life and health insurance risks, scenarios that are defined as either:

-

∙ a change in future assumptions; or

-

∙ a fixed stress independent of assumptions.

-

-

∙ For counterparty default risk, a calculation for each exposure depending on type of exposure, probability of default, variance of loss distribution and amount of collateral.

-

∙ For operational risk, a calculation based on the size of the business defined by various metrics (premiums, reserves, expenses).

Each individual capital requirement is required to be defined so that it is calibrated as a 99.5% VaR over a 1-year period – a “1 in 200 year event”.

Simplified methods can be used where the full requirement is disproportionate to the particular risk. Certain simplifications are specified, but insurers can use other simplifications where these can be justified.

The base SCR (excluding operational risk) is determined from the impact of the capital requirements for individual risks, aggregated using a series of correlation matrices. These use correlation factors between each pair of risks at each level. These factors are specified in the Solvency II Directive or the Delegated Regulation, depending on level.

This process is intended to ensure that the overall result remains consistent with 99.5% VaR over a 1-year period, allowing for the effect of diversification between risks on stressed assumptions.

The base SCR is first calculated without allowing for any change in the value of discretionary benefits or that of deferred taxes, as determined in the technical provisions.

The adjustment for the impact on discretionary benefits is then allowed for by repeating the entire calculation using appropriate revised assumptions for these benefits under each risk scenario and taking the difference from the original SCR calculation; the adjustment is subject to a maximum equal to the total value of discretionary benefits in the calculation of technical provisions.

The impact of deferred taxes is determined by assuming an instantaneous loss equal to the SCR, irrespective of the actual taxation regime.

The SCR for operational risk is then added to the result.

EIOPA (2014) has published a useful document setting out the assumptions made in defining the standard formula parameters.

3.1.2. Comments on general structure

The standard formula is required to be suitable for a broad range of mainly smaller and medium-sized insurers across all EU countries.

It should therefore cover the major risks relevant to these insurers, whilst being sufficiently simple and clear to operate, albeit with the option of using simplified methods where appropriate.

It has proved difficult to gain political approval for aspects of the standard formula, e.g., treatment of securitisation, and there are inevitably compromises between simplicity and universal appropriateness.

The appropriateness of the standard formula, both for general use and where considered in the case of a specific insurer, depends to a significant extent on:

-

∙ the comprehensiveness of the risks covered;

-

∙ the appropriateness and accuracy of the diversification methodology and correlation factors for combining risks; and

-

∙ the accuracy of the calibration of the capital requirements for individual risks.

3.1.3. Risks covered

The following are examples of significant risks relevant to certain life insurers, which are not covered by the standard formula:

Further information relating to some of these risks is given in EIOPA (2014).

3.1.3.1. Risks to market values and technical assumptions

Risk of change in:

-

∙ interest rate term structure other than increase/decrease at all durations, e.g., twist;

-

∙ interest rate volatility;

-

∙ spread between government bond yields and swaps;

-

∙ equity volatility;

-

∙ inflation rate (other than in relation to expenses);

-

∙ mortality improvement trend.

These risks have presumably been omitted on grounds of either ensuring the simplicity of the standard formula or limited applicability, or possibly in some cases on political grounds, and could have been included if considered appropriate. This has been helpful for those insurers in Germany that had been selling interest rate volatility by investing in callable bonds to enhance yield and to United Kingdom with-profit funds with high equity backing ratios.

3.1.3.2. Other risks

-

∙ Risk of change in the legal, fiscal or regulatory environment.

-

∙ Liquidity risk.

-

∙ Contagion risk.

-

∙ Risks from strategic decisions.

-

∙ Risks to the insurer’s reputation.

-

∙ Risk of change in terms of external contracts relevant to the evaluation of technical provisions, e.g., rebates received from external investment managers.

These risks are inappropriate for the standard formula, due to either the particular risk requiring a solution other than holding additional capital or the difficulty of providing a standard definition of capital required. Some of these risks should be managed through the general risk management systems operated by the insurer.

Nevertheless, insurers are required to consider all relevant risks in the ORSA, and must specifically consider whether there are risks not covered by the standard formula which require additional capital.

3.1.4. Correlation and diversification

The methodology used in the standard formula, which determines the capital required for each risk separately, at the same level (99.5% VaR/1 year) as the overall capital requirement, and then uses correlation matrices to allow for diversification between risks, has the advantage of conceptual, operational and mathematical simplicity. The impact of diversification on the SCR can be highly material, particularly where there is no single dominant risk. For example, Aviva (2017, page 30) reported total diversification benefit at end-2016 of £5.2bn (about 30% of pre-diversification SCR). Although this relates to an internal model rather than the standard formula, it illustrates the significance of diversification to Solvency II results.

However, it is subject to a number of valid criticisms:

-

∙ The methodology makes no allowance for the combined impacts of risks. This can operate either to increase or decrease overall capital required: e.g., the combined impact of a mass lapse stress with most other stresses would result in an overall reduction in required capital compared with both considered separately; on the other hand, for an insurer subject to guaranteed annuity options, the combined impact of an interest rate down stress and a longevity stress is likely to be higher than with both considered separately.

-

∙ There are alternative methodologies which allow for the combination of risks, but these significantly increase the complexity of the modelling required to determine the results.

-

∙ The capital requirement is based on extreme downside risks, and as a result the diversification approach should consider correlations between risks in extreme downside circumstances (“tail dependency” and “asymmetry”), which might be expected to differ from correlations observed in normal circumstances. This makes it very difficult to evaluate the correlation factors, as available data might not be considered relevant to the circumstances. A significant degree of judgement was therefore used in defining the factors. This has resulted in a broad approach, with simply determined factors; e.g., each specified correlation factor used in the standard formula is one of 1, 0.75, 0.5, 0.25, 0 or −0.25.

Nevertheless, the methodology used appears to result in a reduction for diversification which subjectively appears to be reasonable in many cases. It may therefore be considered that the advantage of standardising on a relatively simple method outweighs these criticisms.

3.1.5. Assessment of the appropriateness of the standard formula in the ORSA

Insurers using the standard formula are required to carry out an assessment of whether the assumptions used in the standard formula are appropriate, allowing for the specific risk profile of the insurer.

This must consider risks not covered by the standard formula as well as risks where the standard formula assumptions and parameters are not appropriate for the insurer’s risk profile.

In the event of there being significant deviations between the risk profile and the standard formula, insurers are expected to consider how this situation can be addressed. EIOPA guidance suggests developing a partial or full internal model, de-risking and aligning the risk profile with the standard formula as solutions to this. These solutions do not appear to recognise that they may be impractical where the problem lies primarily in the definition of the standard formula rather than with the insurer’s risk profile. For example, an insurer which is subject to higher longevity risk than covered by the standard formula, due to having a long liability profile, cannot readily de-risk or re-align its liabilities.

The regulator is permitted to require a capital add-on where the risk profile is significantly different, though this is intended to be temporary until the situation has been addressed. It is not clear what would happen if none of the above solutions work on a permanent basis.

Where elements of the standard formula understate the risk for an insurer, it is possible that other elements overstate the risk, and in these circumstances the insurer may wish to offset decreases in capital against increases. The Delegated Regulation relating to capital add-ons imposes strict conditions on data and methodology used to justify the reduction when applying such offsetting. Furthermore, at least one regulator has indicated that these conditions should also be applied in the case of the assessment within the ORSA.

Unless all elements of the standard formula are demonstrably appropriate for the insurer, this assessment appears to impose either additional capital requirements or a significant additional analytical burden on small and medium insurers, for whom internal models may not be appropriate.

3.1.6. Comments on the definition and calibration of individual stresses

This section includes commentary on the definitions of selected individual stresses used in the standard formula. For stresses where no comments are made, no implication is intended that the definition is considered to be fully appropriate.

3.1.6.1. Longevity risk

The scenario is a reduction of 20% in future assumed mortality rates. This was determined with regard to research mostly undertaken using data for annuities in payment.

Although the research had regard to changes in mortality trends, it was decided to express the stress as a level reduction in future mortality rates rather than an increase in the improvement trend, which might appear to be a more likely scenario; this was presumably on grounds of operational simplicity, even though amending the longevity trend assumption does not appear to be particularly challenging.

As the research had regard to annuities in payment, the determination of the stress as a level reduction rather than a trend increase might be considered inadequate for insurers exposed to longevity risk arising from deferred annuities at younger ages.

3.1.6.2. Lapse risk

The capital requirement is the most onerous of the following scenarios:

-

∙ 50% increase in assumed lapse rates for policies where lapsing increases technical provisions.

-

∙ 50% reduction in assumed lapse rates for policies where lapsing reduces technical provisions.

-

∙ mass lapse of 40% of all policies where lapsing increases technical provisions (70% for certain group pensions contracts).

The determination of whether lapsing increases or reduces technical provisions is required to be carried out at individual policy level. Whilst it clearly is sensible to allow for policyholder behaviour in evaluating lapse risk (e.g. where a policy provides a valuable guarantee, a reduction in lapse rates might be expected in extreme conditions), carrying out such calculations at individual policy level brings practical difficulties. Furthermore, such differential policyholder behaviour is unlikely to be exhibited where, e.g., lapsing increases technical provisions for larger policies and reduces technical provisions for smaller policies of the same type, due to the fixed nature of the expense provision.

It is thought that many insurers adopt a simplification, so that the determination of which scenario to apply is carried out at product class level rather than individual policy level. It is considered that the requirement could reasonably have been expressed to permit this without classification as a simplification.

On the other hand, as informed policyholders can be expected to be more likely to lapse where financially advantageous and less likely where disadvantageous, it might be considered more appropriate to include both the increase and decrease scenarios in the overall capital requirement (subject to a diversification calculation with negative correlation factor) rather than simply taking the higher of the two.

The mass lapse scenario is unusual, in that the scenario is defined in absolute terms rather than with reference to the insurer’s own assumptions. This scenario must consider the situation where there is a catastrophic change in the insurer’s public reputation or there are external factors affecting customer psychology, in particular where the concept and security of life insurance is publicly discredited, or both.

It is clear that there is limited actual data relevant to the assessment of such situations – EIOPA (2014) has stated that the empirical basis to calibrate the mass lapse event is scarce. It appears that the 40% rate was determined largely subjectively, perhaps influenced by those who take the view that the inclusion of value of future profits within technical provisions should have been limited under Solvency II. It should be considered inappropriate to use the same mass lapse assumption for all insurers irrespective of the product type, the stability of the markets in which the insurers operate and the insurers’ actual lapse experience. It is therefore likely that the 40% rate is too high for many insurers. The prospect of a market in mass lapse risk transfer has been suggested (Horley and Gingell, Reference Horley and Gingell2016). Were such a market to develop, it would provide a means of mitigating the Solvency II capital requirement, and may indeed demonstrate that the capital requirement is over-prudent.

Furthermore, there are varied interpretations of the treatment of future expenses under this scenario.

3.1.6.3. Life catastrophe risk

The capital requirement is based on the assumption of a catastrophe causing additional deaths of 1.5 pro mille during the next year.

This can be considered to be very modest in comparison to the impact of historical pandemics, e.g., the 1918 influenza pandemic, and indeed wars. However, this may be justifiable on the grounds that public authorities’ understanding and control of the spread of pandemics has substantially and permanently improved since the time when pandemics were more common and severe, particularly in areas like the EU. One can only hope that this remains so.

At a more technical level, there is an inconsistency between the definitions of the standard formula for life catastrophe risk and for health catastrophe risk – this is also required for life insurers who write income protection and critical illness policies.

Whereas life catastrophe only includes an unspecified risk which can be regarded as covering risk of pandemics and wars, health catastrophe includes specific elements for mass accident risk (e.g. stadium disasters) and accident concentration risk for writers of group income protection insurance as well as pandemic risk. It is not clear why these additional risks are not also specifically included within life catastrophe – in particular accident concentration risk is relevant to insurers of group life business.

3.1.6.4. Interest rate risk

The two scenarios to be considered are upwards and downwards changes to the yield curve, defined as percentages of the yield at each duration, the percentages reducing with increasing duration. The upwards changes are subject to a minimum of 1 percentage point at each duration, which applies throughout the curve in current conditions. There is no corresponding minimum change on downwards changes, and in current low-rate conditions, the stresses are very low.

As the base yield curve moves to the UFR at long durations, it is not clear why the scenario effectively includes stresses to this rate, which was defined with regard to considerations that were considered relatively stable in the long term, though the EIOPA review (see Appendix 2) may amend this.

There are many possibilities for changes to the shape of the yield curve, and other potential scenarios might be more onerous for individual insurers. Clearly, the standard formula must limit the number of scenarios to be investigated, but additional scenarios such as twists (increases at short durations and decreases at long durations and vice versa) might have been appropriate.

3.1.6.5. Equity risk

The basic scenario is a 39% reduction in value for equities listed in EEA or OECD countries and a 49% reduction for other equities.

This is subject to a “symmetric adjustment” of up to 10 percentage points in either direction, based on the relative value of an equity index in comparison with a 3-year average. This is justified on the grounds that equities have historically demonstrated an element of mean reversion. The symmetric adjustment can work well in immunising the solvency ratio against short-term fluctuations in equity values, though the fixed nature of the 10% limit may give problems in practice after an equity crash where an insurer is concerned about maintaining solvency following a further reduction. Perhaps a removal of the limit could be considered to reduce pro-cyclicality risk during rapid and extreme market falls.

3.1.6.6. Spread risk

The requirements to determine capital for spread risk are very complicated, covering 12 pages of the Delegated Regulation. The capital required is based on type of instrument, with many sub-classes and exceptions, and for each class the stress depends on the rating and duration of each instrument. Unlike most other modules, these requirements are defined in the style of capital charges for each asset type rather than being scenario-based.

A particularly noteworthy feature is that EU government bonds denominated in the domestic currency are regarded as risk-free, notwithstanding the crisis affecting certain Eurozone members.

The Delegated Regulation was amended in 2016 to reduce capital requirements in respect of spread risk arising from infrastructure investments, reflecting the European Commission’s Investment Plan for Europe.

3.1.6.7. Currency risk

The capital requirement in respect of each foreign currency other than the insurer’s local currency is the higher of the impact of an increase of 25% or a decrease of 25% against the local currency. All currencies are assumed to move against the insurer at the same time without making allowance for diversification between them.

The increase scenario applies where liabilities exceed assets in the currency, and the decrease scenario where assets exceed liabilities.

An unsatisfactory feature of this requirement is where an insurer backs the exposure of the SCR and/or risk margin to a foreign currency with assets in the same currency, in order to minimise currency risk. This generates an additional capital requirement, because the scenario does not amend the value of the SCR or risk margin.

3.1.6.8. Counterparty default risk

Like spread risk, the requirements are also very complicated, and cover 13 pages of the Delegated Regulation, which include a number of mathematical formulae. This complexity is probably necessary given the number of different types of arrangement that must be covered, as for a few insurers these risks are significant.

For most insurers, these risks are not material, and although it is helpful that EIOPA have provided worksheets which produce the results, a simpler approach relevant to most insurers would have been welcome.

3.1.6.9. Operational risk

A very simple factor-based approach has been adopted, on the overall assumption that a standardised level of risk management is present, and therefore operational risk can be defined in terms of standard metrics reflecting the size of the insurer.

The approach is completely different between traditional business, where the metrics used are premiums or reserves, and unit-linked business, where the metric used is renewal expenses.

Although the overall assumption of a standardised level of risk management is unlikely to be true in practice, it is difficult to see how a different approach could be adopted in practice for the standard formula, unless some judgemental discretion is given to the regulator in relation to the assessment of the quality of risk management.