1. Introduction

Phosphorus (P) is a constituent of essential biomolecules for plant growth and survival (Lambers, Reference Lambers2022). Inorganic orthophosphate (H2PO4−, HPO42−; Pi) is the predominant form of P directly acquired by plant roots. However, Pi is limited by its low solubility and mobility in the soil (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Mylavarapu, Harris and Colee2022). Large amounts of chemical Pi fertilizers are applied during agricultural practices to alleviate low P availability, yet plants take up only 20–30% of the applied Pi fertilizer (McDowell & Haygarth, Reference McDowell and Haygarth2024). Targeting genes that increase phosphorus use efficiency (PUE) is an alternative strategy to circumvent the long-term consequences of excessive P fertilizer in agricultural systems. Genes related to the mobilization and recycling of cellular P fractions are promising candidates for increased PUE (Han et al., Reference Han, White and Cheng2022).

P in plants can be grouped into organic and inorganic fractions based on their chemical structure. Organic P (Po) includes nucleic acids, glycerophospholipids and low-molecular-weight phospho-ester (P-ester) fractions (Suriyagoda et al., Reference Suriyagoda, Ryan, Gille, Dayrell, Finnegan, Ranathunge, Nicol and Lambers2023; Tsujii et al., Reference Tsujii, Fan, Atwell, Lambers, Lei and Wright2023). Nucleic acids represent the predominant sink (>50%) for Po in plant leaves, with approximately 50% of these present as ribosomal RNA (rRNA), followed by organellar DNA (7%), tRNA (2%) and mRNA (1%) (Busche et al., Reference Busche, Scarpin, Hnasko and Brunkard2021). Phospholipids (PLs, P-lipids) constitute the second most abundant fraction of Po (30%) in plant cells (Busche et al., Reference Busche, Scarpin, Hnasko and Brunkard2021). They are synthesized primarily in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which accounts for >60% of cellular PLs by mass (Lagace & Ridgway, Reference Lagace and Ridgway2013). Finally, low-molecular-weight P-esters comprise phosphorylated metabolites, free nucleotides and phosphorylated proteins that amount to 20% of Po in plant cells (Busche et al., Reference Busche, Scarpin, Hnasko and Brunkard2021). The diversity of chemical structures found in low-molecular-weight P-esters makes this fraction the most diverse in plants (Busche et al., Reference Busche, Scarpin, Hnasko and Brunkard2021).

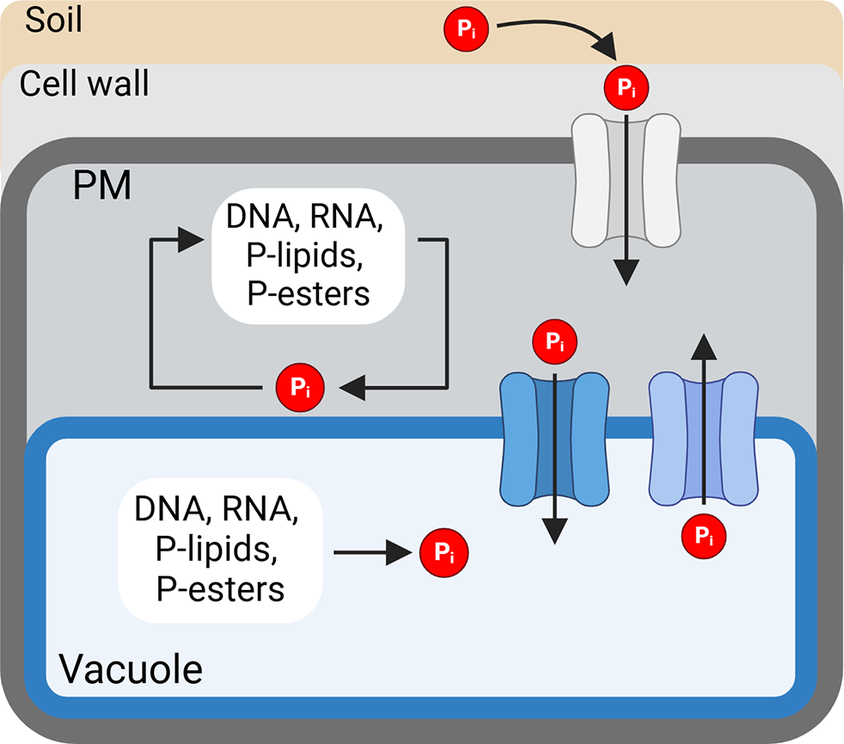

Pi is the predominant form of inorganic phosphate in plants, with a small portion existing as pyrophosphate (P2O74−) (Tsujii et al., Reference Tsujii, Fan, Atwell, Lambers, Lei and Wright2023). As mentioned above, Pi is neither easily accessible nor evenly distributed due to its low solubility and poor mobility in the soil (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Mylavarapu, Harris and Colee2022). Pi is directly absorbed by the roots and transported within the plants through the action of membrane-localized Pi transporters. Under sufficient P, up to 75% of excess cellular Pi is stored in the vacuoles through the action of vacuolar transporters (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yang, Luan, Wang, Zhang, Zhang, Shi, Zhao, Lan and Luan2015; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Huang, Yang, Hong, Huang, Wang, Chiang, Tsai, Lu and Chiou2016). Upon Pi limitation, Pi is exported from the vacuole to buffer changes in cytosolic Pi levels (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yang, Luan, Wang, Zhang, Zhang, Shi, Zhao, Lan and Luan2015; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Huang, Yang, Hong, Huang, Wang, Chiang, Tsai, Lu and Chiou2016; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Zhao, Wan, Liu, Xu, Tian, Ruan, Wang, Deng, Wang, Dolan, Luan, Xue and Yi2019). Pi recycling, import and storage inside the vacuole are crucial for maintaining a functional level of cellular metabolism (Yoshitake & Yoshimoto, Reference Yoshitake and Yoshimoto2022).

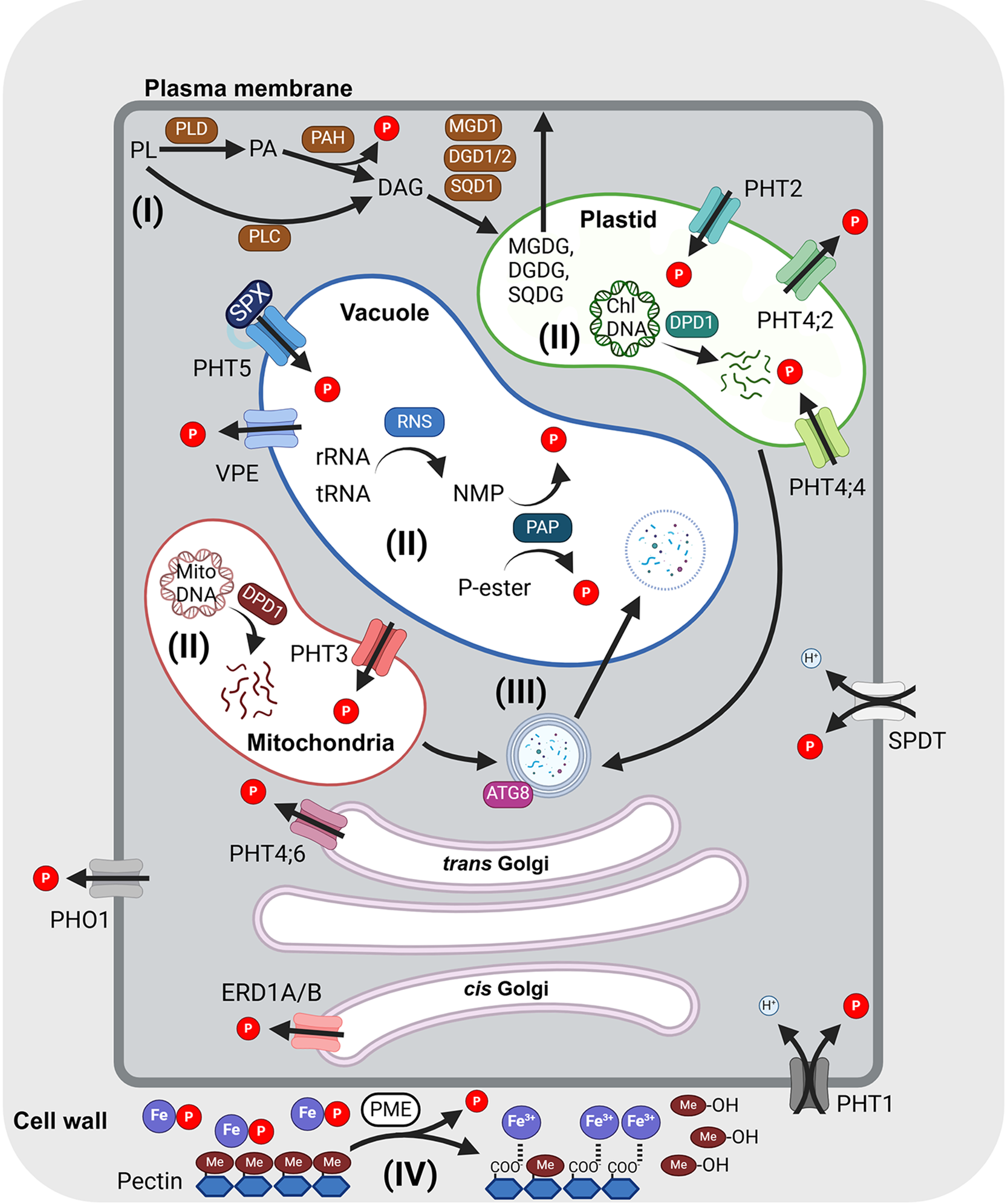

It is crucial to control the mobilization and recycling of intracellular P, especially when external P availability fluctuates. Pi mobilization and recycling strategies vary in their targets and cellular localization, as outlined in Figure 1. Pi is mobilized through Pi transporters on the plasma and organellar membranes. Additionally, intracellular P-containing biomolecules such as nucleic acids and PLs can be metabolized to release Pi to adjust cytosolic Pi concentrations (Yoshitake & Yoshimoto, Reference Yoshitake and Yoshimoto2022). Recent studies also revealed that Pi can be remobilized from the cell wall (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Zhu, Zhao, Zheng and Shen2016; Qi et al., Reference Qi, Ye, Xiaolong, Xiaoying, Jixing, Renfang and Xiaofang2022). Other aspects of P starvation responses (PSRs), such as those related to Pi acquisition, transport and regulation of local and systemic P signalling, have been covered and discussed in recent reviews (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Kuo and Chiou2021; Yoshitake & Yoshimoto, Reference Yoshitake and Yoshimoto2022; Puga et al., Reference Puga, Poza-Carrion, Martinez-Hevia, Perez-Liens and Paz-Ares2024; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Lin, Hsiao and Chiou2024). This review will focus on intracellular Pi recycling, mobilization and the corresponding regulation. Notably, many of these strategies are regulated by a central module of transcriptional activation by PHOSPHATE STARVATION RESPONSE (PHR) and suppression by (SYG1/PHO81/XPR1) SPX proteins with inositol pyrophosphates (PP-InsPs) as signals of intracellular P status (Puga et al., Reference Puga, Mateos, Charukesi, Wang, Franco-Zorrilla, de Lorenzo, Irigoyen, Masiero, Bustos, Rodriguez, Leyva, Rubio, Sommer and Paz-Ares2014; Wild et al., Reference Wild, Gerasimaite, Jung, Truffault, Pavlovic, Schmidt, Saiardi, Jessen, Poirier, Hothorn and Mayer2016; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Ma, Sui, Wei, Satheesh, Zhang, Ge, Li, Zhang, Wittwer, Jessen, Zhang, An, Chao, Liu and Lei2019; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Lau, Puschmann, Harmel, Zhang, Pries, Gaugler, Broger, Dutta, Jessen, Schaaf, Fernie, Hothorn, Fiedler and Hothorn2019). Finally, we highlight the gaps in our current understanding of Pi recycling and P sensing, and the coordination between recycling and remobilization and the potential use of the key genes from these strategies as targets for improving PUE in crops.

Figure 1. Strategies for intracellular P recycling and mobilization in plant cells.

Different pathways for intracellular Pi recycling and mobilization are outlined as follows: (I) Lipid remodelling at the plasma membrane, (II) degradation of nucleic acids, (III) autophagy and (IV) Pi remobilization from the cell wall. Pi mobilization is mediated by PHT1 Pi transporters, PHOSPHATE 1 (PHO1) and SULTR-like phosphorus distribution transporter (SPDT) across the plasma membrane, PHT2 and PHT4 in the plastids, PHT3 in the mitochondria and PHT5 and vacuolar phosphate efflux (VPE) on the vacuolar membrane. PHT4;6 and ER retention defective 1A/B (ERD1A/B) are located in the trans-Golgi and cis-Golgi, respectively. The arrows indicate the transport direction. Metabolic genes involved in P recycling are labelled as follows: autophagy-related 8 (ATG8), defective in pollen organelle DNA degradation1 (DPD1), DIGALACTOSYL DIACYLGLYCEROL DEFICIENT 1/2 (DGD1/2), pectin methyltransferase (PME), phospholipase C (PLC), phospholipase D (PLD), phosphatidic acid phosphatase (PAH), ribonuclease 2 (RNS2), sulphoquinovosyldiacylglycerol 1 (SQD1), purple acid phosphatase (PAP). Organic and inorganic phosphates are labelled as follows: diacylglycerol (DAG), digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG), methanol (Me-OH), monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG), phosphatidic acid (PA), phospholipid (PL) and sulphoquinovosyldiacylglycerol (SQD) (see the text for details). This figure was created using BioRender.

2. P i transporters in P mobilization

Pi transporters located on the plasma membrane, which carry Pi in and out of cells, are primarily responsible for uptake from the soil by importing Pi or exporting Pi as a means to translocate Pi between tissues. On the other hand, organellar Pi transporters deliver Pi across organellar membranes to modulate the cytosolic Pi concentration and the Pi concentration inside the organelles (Figure 1). The coordination of these transport activities is essential for controlling cytosolic Pi concentrations. There are three types of Pi transporter families located in plasma membranes: members of the Pi transporter 1 (PHT1), PHOSPHATE1 (PHO1) and SULTR-like Pi distribution transporter (SPDT) families (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Lin, Hsiao and Chiou2024). PHT1 members are primarily responsible for initial Pi acquisition from the roots and subsequent Pi allocation among various tissues and organs. PHO1 members are Pi efflux transporters predominantly expressed in the root pericycle and xylem parenchyma cells for Pi loading into the xylem (Hamburger et al., Reference Hamburger, Rezzonico, MacDonald-Comber Petetot, Somerville and Poirier2002). PHO1 members are also expressed in the seed coat, essential for transferring Pi from maternal to filial tissues to sustain seed development (Vogiatzaki et al., Reference Vogiatzaki, Baroux, Jung and Poirier2017; Che et al., Reference Che, Yamaji, Miyaji, Mitani-Ueno, Kato, Shen and Ma2020; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Zhang, Gao, Wang, Li, Wang, Liu, Lin, Liu, Wang, Li, Deng, Tang, Luan and He2021; Ko et al., Reference Ko, Lu, Hung, Chang, Li, Yeh and Chiou2024). SPDTs are node-localized Pi transporters responsible for loading Pi into grains in rice (Yamaji et al., Reference Yamaji, Takemoto, Miyaji, Mitani-Ueno, Yoshida and Ma2017) and barley (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Huang, Hisano, Ding, Huang, Mitani-Ueno, Yokosho, Sato, Yamaji and Ma2022). Knockout of rice SPDTs reduces grain Pi loading and phytic acid synthesis without any penalty on the yield (Yamaji et al., Reference Yamaji, Takemoto, Miyaji, Mitani-Ueno, Yoshida and Ma2017). Arabidopsis SPDT members are expressed in the rosette basal region and leaf petiole and preferentially allocate Pi to younger leaves (Ding et al., Reference Ding, Lei, Yamaji, Yokosho, Mitani-Ueno, Huang and Ma2020).

As to the organellar Pi transporters, PHT2 transporters are localized in the chloroplasts, PHT3 transporters are in the mitochondria, PHT4 members are in the plastids or Golgi apparatus and PHT5 (or vacuolar Pi transporter (VPT)) and vacuolar Pi efflux (VPE) are VPTs (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Lin, Hsiao and Chiou2024). The chloroplast and mitochondrial Pi transporters are essential for sustaining photosynthetic activity and ATP generation (Flugge et al., Reference Flugge, Hausler, Ludewig and Gierth2011; Jia et al., Reference Jia, Wan, Zhu, Sun, Zheng, Liu and Huang2015; Raju et al., Reference Raju, Kramer and Versaw2024). VPTs are critical in buffering cytosolic Pi levels (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yang, Luan, Wang, Zhang, Zhang, Shi, Zhao, Lan and Luan2015; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Huang, Yang, Hong, Huang, Wang, Chiang, Tsai, Lu and Chiou2016; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Zhao, Wan, Liu, Xu, Tian, Ruan, Wang, Deng, Wang, Dolan, Luan, Xue and Yi2019). In the following section, we will discuss the roles of the vacuolar and organellar Pi transporters in intracellular Pi remobilization and recycling.

2.1. Vacuolar Pi transporters

Under sufficient Pi supply, most intracellular Pi is sequestered in the vacuoles, the largest organelle in plant cells (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Huang, Kuo and Chiou2017). When Pi supply is scarce, Pi is released from the vacuoles to meet demand in the cytoplasm. Two types of VPTs mediate Pi sequestration and liberation, respectively: influx transporter PHT5, responsible for Pi storage inside vacuoles (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yang, Luan, Wang, Zhang, Zhang, Shi, Zhao, Lan and Luan2015; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Huang, Yang, Hong, Huang, Wang, Chiang, Tsai, Lu and Chiou2016), and the VPE transporter, required for exporting Pi from vacuoles (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Zhao, Wan, Liu, Xu, Tian, Ruan, Wang, Deng, Wang, Dolan, Luan, Xue and Yi2019). Both Pi transporters belong to the major facilitator superfamily (MFS), in which PHT5 members contain an additional SPX domain at their N terminus involved in regulating their transport activity (Luan et al., Reference Luan, Zhao, Sun, Xu, Fu, Lan and Luan2022).

The SPX domain of the PHT5 members binds to PP-InsPs and is implicated in Pi sensing and signalling. Removal of the N-terminal 229 amino acids (including the SPX domain) of PHT5 constitutively turns on its transport activity. Still, mutation of the conserved PP-InsP binding pocket in the SPX domain abolishes this activity (Luan et al., Reference Luan, Zhao, Sun, Xu, Fu, Lan and Luan2022). A recent study showed that loss of function of VHA-A, an essential subunit of vacuolar H+-ATPase, increased the vacuolar pH value but reduced the vacuolar Pi concentration (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Luan, Xue, Yan and Lan2024). It is unclear how the change in the acidification of the vacuolar lumen affects the transport activity of PHT5, because its Pi transport activity is independent of ATP and the H+ gradient when examined in yeast vacuoles (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Huang, Yang, Hong, Huang, Wang, Chiang, Tsai, Lu and Chiou2016). One plausible explanation is that PHT5-mediated transport could be facilitated by the positive inside potential across the tonoplast. The concentration gradient would be generated by protonating the divalent Pi (HPO42−) to monovalent Pi (H2PO4−) inside the acidic vacuolar lumen (Massonneau et al., Reference Massonneau, Martinoia, Dietz and Mimura2000; Versaw & Garcia, Reference Versaw and Garcia2017). In rice, the expression of OsPHT5 (SPX-MFS1 and SPX-MSF2) was post-transcriptionally suppressed by microRNA827 (miR827) upon Pi starvation (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Santi, Jobet, Lacut, El Kholti, Karlowski, Verdeil, Breitler, Perin, Ko, Guiderdoni, Chiou and Echeverria2010; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Huang, Ying, Li, Secco, Tyerman, Whelan and Shou2012). This regulation may also apply to non-Brassicales species (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Lin, Chiang, Syu, Hsieh and Chiou2018). The OsPHT5 activity is shown to be modulated by its trafficking from pre-vacuolar compartments to the vacuolar membrane by interacting with the syntaxin of plants (OsSYP21 and OsSYP22) with its SPX domain (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Zhang, Qian, Ying, Liao, Gan, Mao, Wang, Whelan and Shou2023). Unlike PHT5, the gene expression of rice VPE is upregulated by OsPHR2 under Pi starvation (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Zhao, Wan, Liu, Xu, Tian, Ruan, Wang, Deng, Wang, Dolan, Luan, Xue and Yi2019).

Loss-of-function pht5 Arabidopsis mutants led to low vacuolar Pi content and necrotic leaves during P replenishment after starvation (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Huang, Yang, Hong, Huang, Wang, Chiang, Tsai, Lu and Chiou2016). Overexpression of PHT5 resulted in over-accumulation of Pi inside the vacuole, resulting in reduced cytosolic Pi concentrations leading to retarded growth and upregulation of Pi starvation-responsive genes even under Pi sufficiency (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Huang, Yang, Hong, Huang, Wang, Chiang, Tsai, Lu and Chiou2016). Overexpression of PHT5 also retained more Pi in the leaves and impaired Pi allocation to flowers (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Luan, Wen, Wang and Lan2023). In contrast to PHT5, overexpressing VPE in rice reduced Pi accumulation in vacuoles, whereas vpe mutants displayed a higher vacuolar Pi level (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Zhao, Wan, Liu, Xu, Tian, Ruan, Wang, Deng, Wang, Dolan, Luan, Xue and Yi2019).

2.2. miR399- and miR827-mediated Pi transport

MicroRNA399 (miR399) and miR827 are well-studied Pi-starvation-induced microRNAs that regulate cytosolic Pi homeostasis (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Lin, Huang and Chiou2014; Chien et al., Reference Chien, Chiang, Wang and Chiou2017). MIR399 and MIR827 genes are evolutionarily conserved (Hsieh et al., Reference Hsieh, Lin, Shih, Chen, Lin, Tseng, Li and Chiou2009; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Lin, Chiang, Syu, Hsieh and Chiou2018) and serve as long-distance signalling molecules for systemic regulation (Chien et al., Reference Chien, Chiang, Leong and Chiou2018). MiR399 suppresses the expression of PHO2, which encodes a ubiquitin-conjugating E2 enzyme (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Chiang, Lin, Chen, Tseng, Wu and Chiou2008; Kuo & Chiou, Reference Kuo and Chiou2011). PHO2 proteins localized in the ER and Golgi regulate the protein stability of PHT1 and PHO1 transporters to control Pi uptake and root-to-shoot translocation activities, respectively (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Huang, Tseng, Lai, Lin, Lin, Chen and Chiou2012; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Han, Lin, Chen, Tsai, Chen, Chen, Lin, Chen, Liu, Chen, Sun and Chiou2013). Overexpression of miR399 or loss of function of PHO2 enhances Pi uptake and translocation and leads to over-accumulation of Pi in shoots (Aung et al., Reference Aung, Lin, Wu, Huang, Su and Chiou2006; Chiou et al., Reference Chiou, Aung, Lin, Wu, Chiang and Su2006). MiR827 targets two different transcripts encoding SPX-domain-containing proteins, NITROGEN LIMITATION ADAPTATION (NLA) in Brassicales and PHT5 in non-Brassicales species (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Lin, Chiang, Syu, Hsieh and Chiou2018). As mentioned above, PHT5 is a vacuolar Pi import transporter (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Huang, Ying, Li, Secco, Tyerman, Whelan and Shou2012; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yang, Luan, Wang, Zhang, Zhang, Shi, Zhao, Lan and Luan2015; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Huang, Yang, Hong, Huang, Wang, Chiang, Tsai, Lu and Chiou2016). NLA encodes a plasma membrane-localized ubiquitin E3 ligase belonging to the SPX-RING protein family (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Huang and Chiou2013). NLA regulates the degradation of PHT1 by ubiquitination-mediated endocytosis (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Huang and Chiou2013). Overexpression of miR827 and loss of function of nla mutants impaired Pi remobilization from older to young leaves in rice (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Huang, Ying, Li, Secco, Tyerman, Whelan and Shou2012) and accumulated higher amounts of Pi in Arabidopsis leaves (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Huang and Chiou2013; Val-Torregrosa et al., Reference Val-Torregrosa, Bundo, Mallavarapu, Chiou, Flors and San Segundo2022). Of note, the upregulation of miR399 and miR827 by low Pi and the function of PHO2 and NLA in regulating Pi transport are evolutionarily conserved (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Lin, Chiang, Syu, Hsieh and Chiou2018).

2.3. PP-InsP-SPX-PHR module

PHR1 in Arabidopsis and PHR2 in rice are considered the central regulators of PSRs in plants (Rubio et al., Reference Rubio, Linhares, Solano, Martin, Iglesias, Leyva and Paz-Ares2001; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Jiao, Wu, Li, Wang, He, Zhong and Wu2008). PHR1 binds to the PHR1-binding sequence (P1BS) cis-element, preferentially found in genes responding to Pi starvation. The PHR1 transcript and protein level are weakly responsive to Pi starvation. However, PHR1-mediated upregulation of PSR is repressed through its interaction with SPX proteins (Puga et al., Reference Puga, Mateos, Charukesi, Wang, Franco-Zorrilla, de Lorenzo, Irigoyen, Masiero, Bustos, Rodriguez, Leyva, Rubio, Sommer and Paz-Ares2014; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ruan, Shi, Zhang, Xiang, Yang, Li, Wu, Liu, Yu, Shou, Mo, Mao and Wu2014b). Interestingly, several SPX transcripts are upregulated by PHR during Pi starvation, which indicates that SPX proteins are involved in a negative feedback regulatory loop with PHR (Puga et al., Reference Puga, Mateos, Charukesi, Wang, Franco-Zorrilla, de Lorenzo, Irigoyen, Masiero, Bustos, Rodriguez, Leyva, Rubio, Sommer and Paz-Ares2014).

Recent studies have identified PP-InsPs as signalling molecules for sensing intracellular P status (Wild et al., Reference Wild, Gerasimaite, Jung, Truffault, Pavlovic, Schmidt, Saiardi, Jessen, Poirier, Hothorn and Mayer2016; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Ma, Sui, Wei, Satheesh, Zhang, Ge, Li, Zhang, Wittwer, Jessen, Zhang, An, Chao, Liu and Lei2019; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Lau, Puschmann, Harmel, Zhang, Pries, Gaugler, Broger, Dutta, Jessen, Schaaf, Fernie, Hothorn, Fiedler and Hothorn2019). PP-InsPs were able to bind to the SPX-containing proteins from various organisms (Wild et al., Reference Wild, Gerasimaite, Jung, Truffault, Pavlovic, Schmidt, Saiardi, Jessen, Poirier, Hothorn and Mayer2016). The genetic analyses of genes encoding diphosphoinositol pentakisphosphate kinases VIH1/2 revealed that bis-diphosphoinositol tetrakisphosphate (1,5-InsP8) acts as an intracellular signalling molecule that translates the cellular Pi status to PSR in plants (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Ma, Sui, Wei, Satheesh, Zhang, Ge, Li, Zhang, Wittwer, Jessen, Zhang, An, Chao, Liu and Lei2019; Ried et al., Reference Ried, Wild, Zhu, Pipercevic, Sturm, Broger, Harmel, Abriata, Hothorn, Fiedler, Hiller and Hothorn2021). Under sufficient P, the binding of InsP8 to SPX proteins promotes its interaction with PHR1 to prevent its transcriptional activation of PSR genes. Conversely, PHR1 dissociates from SPX1 when the InsP8 level drops under P starvation, which allows PHR1 to bind to the P1BS sites to activate PSR genes.

2.4. Other organelle Pi transporters

Chloroplasts and mitochondria carry out vital metabolic reactions, including photosynthesis, carbon assimilation, respiration and oxidative phosphorylation (Flugge et al., Reference Flugge, Hausler, Ludewig and Gierth2011), which are regulated by optimal Pi concentrations. Pi is delivered into chloroplasts and mitochondria by PHT2, PHT3 and PHT4 transporters (Versaw & Garcia, Reference Versaw and Garcia2017). These organellar Pi transporters mediate the distribution of Pi to balance its concentration between the cytosol and organelles. In Arabidopsis, AtPHT2;1 is a low-affinity Pi transporter located in the chloroplast inner envelope membrane whose expression is independent of external Pi supply but induced by light (Versaw & Harrison, Reference Versaw and Harrison2002). Characterization of the loss-of-function atpht2;1 mutant revealed that PHT2;1 contributes to Pi import into chloroplasts and eventually affects the accumulation of Pi in leaves and the allocation of Pi throughout the plant (Versaw & Harrison, Reference Versaw and Harrison2002; Raju et al., Reference Raju, Kramer and Versaw2024). Similar results were observed for rice OsPHT2;1 (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang, Wang, Yan, Yang, Xie, Hu, Shen, Ai, Lin, Xu, Yang and Sun2020).

Arabidopsis has six PHT4 members. Except for PHT4;6, they are localized in the photosynthetic and/or heterotrophic plastids (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Jin, Wussler, Blancaflor, Motes and Versaw2008), among which PHT4;2 has a physiological role in Pi export from root plastids (Irigoyen et al., Reference Irigoyen, Karlsson, Kuruvilla, Spetea and Versaw2011). Although all the PHT4s mediate Pi transport in yeast cells (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Jin, Wussler, Blancaflor, Motes and Versaw2008), interestingly, AtPHT4;4 exhibited ascorbate uptake activity (Miyaji et al., Reference Miyaji, Kuromori, Takeuchi, Yamaji, Yokosho, Shimazawa, Sugimoto, Omote, Ma, Shinozaki and Moriyama2015). PHT4;6 and ER Defective 1A (ERD1A) and ERD1B reside in the Golgi apparatus and are involved in Pi release from the trans- and cis-Golgi compartment, respectively (Cubero et al., Reference Cubero, Nakagawa, Jiang, Miura, Li, Raghothama, Bressan, Hasegawa and Pardo2009). Loss of function of PHT4;6 reduced cytosolic Pi content but enhanced Pi reallocation to the vacuole and activated disease resistance mechanisms (Hassler et al., Reference Hassler, Lemke, Jung, Mohlmann, Kruger, Schumacher, Espen, Martinoia and Neuhaus2012). In contrast, the erd1a mutant altered cell wall monosaccharide composition with increased apoplastic Pi export activity, likely due to exocytosis (Hsieh et al., Reference Hsieh, Suslov, Espen, Schiavone, Rautengarten, Griess-Osowski, Voiniciuc and Poirier2023). PHT4;6 is also required for ammonium and sugar metabolism and mediates dark-induced senescence (Hassler et al., Reference Hassler, Jung, Lemke, Novak, Strnad, Martinoia and Neuhaus2016).

The PHT3 transporters in the inner mitochondrial membrane operate Pi translocation into the mitochondrial matrix (Nakamori et al., Reference Nakamori, Takabatake, Umehara, Kouchi, Izui and Hata2002; Hamel et al., Reference Hamel, Saint-Georges, de Pinto, Lachacinski, Altamura and Dujardin2004). Overexpression of AtPHT3;1 accumulated higher ATP content, faster respiration rate and more reactive oxygen species than wild-type plants, severely hampering plant development (Jia et al., Reference Jia, Wan, Zhu, Sun, Zheng, Liu and Huang2015). The expression of Arabidopsis PHT3 transporters was upregulated by salinity, but overexpressing PHT3 displayed increased sensitivity to salt stress, likely due to the disturbance of ATP and gibberellin metabolism (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Miao, Sun, Yang, Wu, Huang and Zheng2012).

3. Intracellular P recycling

Besides increasing external Pi uptake and release from the vacuole to overcome Pi starvation, Pi recycling is an additional vital system that salvages Pi from many intracellular components that contain P, including from degradation of nucleic acids, membrane lipid remodelling, P remobilization from the cell wall and organelle degradation via catabolic enzymes (labelled I–IV in Figure 1).

3.1. Phosphate scavenging from nucleic acids

Scavenging the Pi from the nucleic acid in leaves during Pi starvation involves the action of hydrolytic enzyme nucleases (RNases) and purple acid phosphatases (PAPs) (Bassham & MacIntosh, Reference Bassham and MacIntosh2017; Yoshitake et al., Reference Yoshitake, Shinozaki and Yoshimoto2022). rRNA is the predominant form of RNA found in most cells; it makes up about 80% of cellular RNA (Palazzo & Lee, Reference Palazzo and Lee2015). The RNS2, a subclass of RNase T2 localized in the vacuoles and ER (Floyd et al., Reference Floyd, Morriss, MacIntosh and Bassham2016), converts RNA into nucleotide monophosphates, which are then dephosphorylated by PAPs. In rice, the expression of both RNSs and PAPs is induced by Pi starvation, which hydrolyses 60–80% of the total RNA in flag leaves to release and remobilize Pi to developing grains (Jeong et al., Reference Jeong, Baten, Waters, Pantoja, Julia, Wissuwa, Heuer, Kretzschmar and Rose2017; Gho et al., Reference Gho, Choi, Moon, Song, Park, Kim, Ha and Jung2020). Other than rRNA, specific transfer RNA (tRNA)-derived fragments (tRFs) from the tRNA cleavage (i.e., tRNAGly and tRNAAsp) by AtRNSs (RNS1–RNS3) were accumulated under Pi starvation (Hsieh et al., Reference Hsieh, Lin, Shih, Chen, Lin, Tseng, Li and Chiou2009; Megel et al., Reference Megel, Hummel, Lalande, Ubrig, Cognat, Morelle, Salinas-Giege, Duchene and Marechal-Drouard2019). In addition to a housekeeping role, RNase-mediated RNA degradation participates in Pi recycling during Pi starvation.

Organelle DNA (orgDNA), which encodes a small genome with multiple copies in vegetative tissues, could also be a source of Pi when degraded (Sakamoto & Takami, Reference Sakamoto and Takami2024). Arabidopsis organellar exonuclease, defective in pollen orgDNA degradation 1 (AtDPD1), operates plastid and mitochondrial DNA degradation during leaf senescence and pollen development (Takami et al., Reference Takami, Ohnishi, Kurita, Iwamura, Ohnishi, Kusaba, Mimura and Sakamoto2018). Loss of function of AtDPD1 inhibits orgDNA degradation under Pi starvation, which maintains a high copy number of chloroplast DNA, leading to compromised PSR gene expression and P remobilization from old to young leaves (Takami et al., Reference Takami, Ohnishi, Kurita, Iwamura, Ohnishi, Kusaba, Mimura and Sakamoto2018; Islam et al., Reference Islam, Yamatani, Takami, Kusaba and Sakamoto2024).

PAPs are Pi starvation-induced acid phosphatases, which hydrolyse phosphomonoesters from various organic P compounds to release Pi at acidic pHs (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Park, Tran, Del Vecchio, Ying, Zins, Patel, McKnight and Plaxton2012). PAPs are localized in intracellular compartments or secreted to extracellular spaces. The secreted PAPs are associated with the root surface and aid in Pi solubilization in the rhizosphere (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Lu, Zhang, Li, Du and Liu2014a; O’Gallagher et al., Reference O’Gallagher, Ghahremani, Stigter, Walker, Pyc, Liu, MacIntosh, Mullen and Plaxton2022). Overexpression of PAP genes improves plant biomass and total P accumulation when Po (e.g., ATP, DNA) is supplied as the sole external P source (Deng et al., Reference Deng, Lu, Li, Du, Liu, Li, Xu, Shi, Shou and Wang2020). Besides conventional phosphatase activity, some PAPs also display phosphodiesterase (Olczak et al., Reference Olczak, Kobialka and Watorek2000; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Lu, Zhang, Li, Du and Liu2014a) or phytase activity (Bhadouria et al., Reference Bhadouria, Singh, Mehra, Verma, Srivastawa, Parida and Giri2017; Kong et al., Reference Kong, Li, Wang, Li, Du and Zhang2018). A broad substrate specificity and widespread localization profiles of PAPs may help plants maintain intracellular Pi balance.

3.2. Phosphate scavenging from membrane lipid remodelling

Membrane lipid remodelling is one of the most dramatic metabolic responses to Pi starvation. It replaces the PLs, such as phosphatidylcholines, phosphatidylglycerol and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), with galactolipid digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG) and sulphoquinovosyldiacylglycerol (SQDG) to release Pi with minimal or no damage to membrane function (Lambers et al., Reference Lambers, Cawthray, Giavalisco, Kuo, Laliberte, Pearse, Scheible, Stitt, Teste and Turner2012). Phospholipase C (PLC), phospholipase D (PLD) and phosphatidic acid phosphatase homolog (PAH) are the major enzymes contributing to PL hydrolysis (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura2013). PLDs work by hydrolysing the phosphodiester bond of PLs to produce phosphatidic acid (PA) and polar head groups (Li et al., Reference Li, Qin, Welti and Wang2006b). PAH then dephosphorylates PAs to form diacylglycerol (DAG) and releases Pi (Nakamura et al., Reference Nakamura, Koizumi, Shui, Shimojima, Wenk, Ito and Ohta2009). PLCs behave differently from PLDs as they produce DAG in a single step to release the P-containing polar head group (Nakamura et al., Reference Nakamura, Awai, Masuda, Yoshioka, Takamiya and Ohta2005; Gaude et al., Reference Gaude, Nakamura, Scheible, Ohta and Dormann2008). In Arabidopsis, two NON-SPECIFIC PLCs (NPC4, 5) and PLDζ (PLDζ1, PLDζ2) are endomembrane localized and their expression is highly induced by Pi starvation (Li et al., Reference Li, Qin, Welti and Wang2006c; Li et al., Reference Li, Welti and Wang2006a; Gaude et al., Reference Gaude, Nakamura, Scheible, Ohta and Dormann2008). Impairment of both PLDζ2 and NPC4 (npc4pldζ2), which increases PE but decreases DGDG, impedes primary root growth and root hair density under Pi deprivation (Su et al., Reference Su, Li, Guo and Wang2018). Mutation in the Arabidopsis PAH, as seen in pah1/pah2 double mutant, suppressed membrane lipid remodelling and showed root growth defects as seen in npc4pldζ2, indicating PL hydrolysis enzymes are important in the Pi recycling under Pi starvation (Nakamura et al., Reference Nakamura, Koizumi, Shui, Shimojima, Wenk, Ito and Ohta2009).

Synthesis of non-P-containing galactolipids and sulpholipids using DAG is another alternative step in membrane lipid remodelling during Pi starvation (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura2013). SQDG biosynthesis is mediated by uridine diphosphate (UDP)-sulphoquinovose synthase 1 and 2 (SQD1 and 2). SQD1 catalyses the assembly of UDP-sulphoquinovose (SQ) via UDP-glucose and sulphite (Sanda et al., Reference Sanda, Leustek, Theisen, Garavito and Benning2001), and then SQD2 functions in transferring the sulphoquinovose of UDP-SQ to DAG to generate SQDG (Yu et al., Reference Yu, Xu and Benning2002). The expression of both SQD1 and 2 is upregulated by Pi limitation (Yu et al., Reference Yu, Xu and Benning2002; Jeong et al., Reference Jeong, Baten, Waters, Pantoja, Julia, Wissuwa, Heuer, Kretzschmar and Rose2017). Knockout of AtSQD2 decreases the amount of SQDG and reduces fresh weight under Pi starvation (Okazaki et al., Reference Okazaki, Otsuki, Narisawa, Kobayashi, Sawai, Kamide, Kusano, Aoki, Hirai and Saito2013).

Monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) is synthesized from DAG by MGDG synthase; subsequently, DGDG can be further synthesized from MGDG by DGDG synthase (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura2013). Arabidopsis has two types of MGDG synthase, Type A (MGD1) and Type B (MGD2 and MGD3) (Awai et al., Reference Awai, Marechal, Block, Brun, Masuda, Shimada, Takamiya, Ohta and Joyard2001). MGD1 is expressed in green tissues and localized in the inner envelope of chloroplasts and plays pivotal roles in photosynthetic membrane biogenesis (Jarvis et al., Reference Jarvis, Dormann, Peto, Lutes, Benning and Chory2000; Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, Kondo, Fukuda, Nishimura and Ohta2007). In contrast, MGD2 and MGD3 localize on the outer envelope membranes of plastids, and their expressions are strongly activated by Pi starvation (Awai et al., Reference Awai, Marechal, Block, Brun, Masuda, Shimada, Takamiya, Ohta and Joyard2001; Jeong et al., Reference Jeong, Baten, Waters, Pantoja, Julia, Wissuwa, Heuer, Kretzschmar and Rose2017). Arabidopsis has two DGDG synthases, AtDGD1 and AtDGD2, and both are induced by Pi deficiency (Kelly & Dormann, Reference Kelly and Dormann2002). In the dgd1 mutant, the DGDG level is significantly reduced, and its growth is impaired under P-deficient conditions (Hartel et al., Reference Hartel, Dormann and Benning2000).

A large number of genes involved in lipid remodelling contain the P1BS motifs in their promoter region, for example, NCP4/5, PLDζ2, PAH1/2, MGD2/3 and SQD1/2 (Pant et al., Reference Pant, Burgos, Pant, Cuadros-Inostroza, Willmitzer and Scheible2015). Loss-of-function Arabidopsis phr1 mutants showed reduced expression of these genes and changes in lipid composition in response to P deficiency (Pant et al., Reference Pant, Burgos, Pant, Cuadros-Inostroza, Willmitzer and Scheible2015), reinforcing the role of PHR1 in membrane Pi recycling.

3.3. Demethylation of pectin enhances cell wall P remobilization

In addition to the intracellular P, pectin in the cell wall has been proposed to contribute to P remobilization from cell wall under Pi starvation (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Wang, Wan, Sun, Wu, Li, Shen and Zheng2015; Qi et al., Reference Qi, Ye, Xiaolong, Xiaoying, Jixing, Renfang and Xiaofang2022). The quasimodo1 (qua1) mutant encoding a glycosyltransferase for pectic synthesis has low pectin content and is more sensitive to P deficiency than the wild-type control (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Wang, Wan, Sun, Wu, Li, Shen and Zheng2015). The carboxyl groups in homogalacturonan (HG), the most abundant pectin subtype, can be demethylated by pectin methylesterase (PME), which liberates protons and methanol and produces a carboxylate group (Wormit & Usadel, Reference Wormit and Usadel2018). It was hypothesized that the negatively charged carboxylate groups on the HG in pectin have a high affinity for Al3+ and Fe3+, which may potentially solubilize P sequestered as the forms of AlPO4 and FePO4 within the cell wall (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Wang, Wan, Sun, Wu, Li, Shen and Zheng2015). OsPME14, the only member of rice PMEs induced by P starvation, may facilitate root cell wall Pi remobilization (Qi et al., Reference Qi, Ye, Xiaolong, Xiaoying, Jixing, Renfang and Xiaofang2022). Overexpressing OsPME14 showed higher PME activity with more cell wall Fe accumulation and soluble P in the root compared to the wild type (Qi et al., Reference Qi, Ye, Xiaolong, Xiaoying, Jixing, Renfang and Xiaofang2022). PME activity is regulated by several factors, such as nitric oxide (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Zhu, Wang, Dong and Shen2017), ethylene (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Zhu, Zhao, Zheng and Shen2016; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wu, Tao, Zhu, Takahashi, Umeda, Shen and Ma2021) and abscisic acid (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Zhao, Wu and Ren Fang2018). Nevertheless, the direct evidence for PME-mediated cell wall P remobilization is still lacking.

3.4. Pi scavenging by autophagy

Autophagy is an intracellular degradation process in vacuoles for bulk protein and organelles to recycle nutrients under starvation (Nakatogawa, Reference Nakatogawa2020). The proteins encoded by autophagy-related genes (ATG) participate in autophagosome induction, membrane delivery, vesicle nucleation, cargo recognition and phagophore expansion and closure (Nakatogawa, Reference Nakatogawa2020). Most ATG genes in Arabidopsis are highly induced by nitrogen starvation but are moderately upregulated by Pi starvation (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Lung, Chou, Lin, Chow, Kuo, Chien, Chiou and Liu2023). Only AtATG8f and AtATG8h were upregulated in the Pi-deprived root, which is mediated by AtPHR1 indirectly (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Chow, Chen, Mitsuda, Chou and Liu2023), suggesting second-wave transcriptional regulation. Low Pi promotes the autophagic flux preferentially in the differential zone of the Arabidopsis root (Naumann et al., Reference Naumann, Müller, Sakhonwasee, Wieghaus, Hause, Heisters, Bürstenbinder and Abel2019; Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Lung, Chou, Lin, Chow, Kuo, Chien, Chiou and Liu2023). Mutation of ATG genes (ATG5, 7, 9 and 10) reduced the Pi translocation to retain more Pi in the root and inhibited meristem development under Pi sufficiency. Autophagy-deficient mutants, atg2 and atg5, showed early depleted Pi and severe leaf growth defects under Pi starvation (Yoshitake & Yoshimoto, Reference Yoshitake and Yoshimoto2022).

ER stress-induced ER-phagy was observed during the early phase of Pi starvation, contributing to Pi recycling and suppressing membrane lipid remodelling, a late PSR (Yoshitake & Yoshimoto, Reference Yoshitake and Yoshimoto2022). In the Pi-starved root apex, ER stress-induced ER-phagy was also observed; however, it is regarded as a sign of local Pi sensing rather than a means for Pi recycling (Naumann et al., Reference Naumann, Müller, Sakhonwasee, Wieghaus, Hause, Heisters, Bürstenbinder and Abel2019). Furthermore, rubisco-containing body-mediated chlorophagy, which contains chloroplast stroma, was formed when Pi limitation was coupled with N and C availability (Yoshitake et al., Reference Yoshitake, Nakamura, Shinozaki, Izumi, Yoshimoto, Ohta and Shimojima2021). Autophagy of organelles plays a role in multiple nutrients recycling, although the mechanism of Pi recycling is relatively unclear.

4. Perspectives and challenges

In plants, Pi recycling involves complex metabolic cascades regulated in response to cellular P-level changes. Studies on Pi recycling have revealed the identity of numerous enzymes that are utilized to convert the diverse biomolecules that comprise cellular Po to Pi. Several questions remain: (1) Is there a preference for which Po fraction to recycle under a limited P supply? However, Po, such as rRNA and PLs, are not completely depleted under limited P supply but are instead regulated due to their essential cellular function. Whether there is a preference regarding which Po fraction recycles Pi under a limited P supply has yet to be explored. With regard to the presentation of P distribution in the current literature, it is worth noting that the most frequently cited studies that provide detailed measurements of Pi content and different types of Po from plants were conducted decades ago. Re-analysing P fractions from plant tissues, cells and organelles through the lens of current advanced techniques, such as mass spectrometry, biosensors and imaging techniques, with spatial and temporal resolution, will provide an up-to-date reference for investigating the effects of Pi recycling on P distribution.

Although we have discussed Pi recycling and mobilization as separate strategies that allow plants to supply and deliver Pi, both methods must act in concert to maintain whole-plant P homeostasis in response to changing P availability. However, a detailed account that describes a coordinated function between recycling and mobilization in response to Pi availability has yet to be formulated. Furthermore, both Pi recycling and Pi mobilization operate in a complex network that must be coordinated to balance the internal cellular Pi level with the external Pi supply. Several components of P recycling and mobilization are known to be controlled by the PP-InsP-SPX-PHR1 module, which suggests a common mode of regulation. The presence of PHR-independent regulation of P recycling and mobilization suggests additional mechanisms remain to be uncovered. Resolving the gaps in our knowledge regarding P recycling, mobilization and signalling will offer information that may be invaluable for ecological and agricultural applications. The genes involved may be used as candidate targets for gene editing or as breeding markers for the future improvement of crop PUE to achieve sustainable agriculture. Nevertheless, as implied by the known interaction between nutrients, such as phosphorus, iron, zinc and nitrogen, balance with other nutrients should be considered when enhancing crop PUE. In the long run, the extent of the potential impacts of high PUE crops on ecology, such as soil microbial, faunal or even other plant communities, should also be evaluated.

Financial support

The authors would like to thank Academia Sinica (AS-GCS-112-L03 and AS-IA-113-L06) and the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC 112-2311-B-001-040-MY3), Taiwan for funding to T.-J. C.’s laboratory.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Author contributions

Chih-Pin Chiang and Joseph Yayen these authors contributed equally. C.-P. C., J. Y. and T.-J. C. conceptualized the review outline. C.-P. C. and J. Y. prepared the figures and wrote the original draft. T.-J. C. compiled, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the critical revision and its final approval.

Comments

Dear Professors Sanders and Dreyer,

Please find enclosed a manuscript entitled “Mobilization and recycling of intracellular phosphorus in response to availability” for consideration for inclusion as a mini-review in the special collection “Quantitative Approaches to Cellular Aspects of Plant Ion Homeostasis” in Quantitative Plant Biology.

Phosphorus (P) is a fundamental element for plant growth and development. Mobilization and recycling of P are hallmark strategies for maintaining cellular P homeostasis in plants. In this mini-review, we have consolidated the relevant advancements in intracellular P mobilization and recycling, particularly under limited P supply. We discuss the recently identified roles of phosphate transporters and the P metabolic enzymes involved, and we also expand on their gene regulation and mechanisms.

We believe this review is timely and will interest the readership of Quantitative Plant Biology. Thank you very much for your kind invitation. We look forward to hearing from you soon.

Sincerely yours,

Tzyy-Jen Chiou

Agricultural Biotechnology Research Center (ABRC), Academia Sinica, Taiwan

tjchiou@gate.sinica.edu.tw