Working mostly in the fields of sociology and medicine, scholars have found that data collected within communities are more representative, provide better interpretive context, and more directly benefit people in need (Bracic Reference Bracic2018; Damon et al. Reference Damon, Callon, Wiebe, Small, Kerr and McNeil2017; De Las Nueces et al. Reference De Las Nueces, Hacker, DiGirolamo and Hicks2012). Community-based research (CBR) involves community members in the research and also uses results of the research to benefit the community (Israel et al. Reference Israel, Schulz, Parker and Becker1998). Although CBR is mutually beneficial, researchers can face challenges recruiting participants and winning the trust of communities. In an age in which digital connections can signal credibility, social media has the potential to facilitate CBR. We introduced a social media component to a longitudinal, CBR project in 2018—seeking to connect with religious leaders through Facebook—to improve response rates, build better community relationships, and facilitate findings distribution. This article presents the results of this initiative, with recommendations for researchers seeking to use social media to accomplish similar goals.

SUCCESSFUL COMMUNITY-BASED RESEARCH

Community-based research (CBR) provides several benefits for both researchers and communities. Projects that are based in a community often have greater validity than projects that are based in a laboratory; researchers can obtain better data and interpret it more accurately when they speak with people in trusting, context-filled conversations (Riffin et al. Reference Riffin, Kenien, Ghesquiere, Dorime, Villanueva, Gardner, Callahan, Capezuti and Reid2016). Additionally, CBR benefits community members who collaborate with researchers to prioritize community needs (Hotze Reference Hotze2011). Communities also benefit when findings are shared, instead of languishing in academic journals. Successful CBR projects have increased condom use and HIV testing among gay and bisexual men (Rhodes et al. Reference Rhodes, Alonzo, Mann, Song, Tanner, Arellano, Rodriguez-Celedon, Garcia, Freeman, Reboussin and Painter2017); demonstrated that Somali communities in the United States are more amenable to violence interventions targeted at gangs than at radicalization (Ellis et al. Reference Ellis, Decker, Abdi, Miller, Barrett and Lincoln2020); and led to the development of culturally appropriate programs for Chinese women who are victims of domestic abuse (Chow and Tiwari Reference Chow and Tiwari2020).

However, CBR relies on voluntary community participation (Riffin et al. Reference Riffin, Kenien, Ghesquiere, Dorime, Villanueva, Gardner, Callahan, Capezuti and Reid2016). Building relationships is a critical but sometimes challenging and time-consuming research step (Teufel-Shone et al. Reference Teufel-Shone, Schwartz, Hardy, De Heer, Williamson, Dunn, Polingyumptewa and Chief2019). To accomplish successful CBR, two interrelated elements are essential: building trust and demonstrating benefits.

Trust is critically important in CBR; community members will not participate if they do not trust researchers (Lucero et al. Reference Lucero, Boursaw, Eder, Greene-Moton, Wallerstein and Oetzel2020). Researchers can build trust by listening to community members and making them partners in the research process. Holding meetings to both speak and listen may seem tedious and repetitive at times, but they are important in building partnerships (Goldberg-Freeman et al. Reference Goldberg-Freeman, Kass, Gielen, Tracey, Bates-Hopkins and Farfel2010), especially if community members are co-leaders (Rickenbacker, Brown, and Bilec Reference Rickenbacker, Brown and Bilec2019). Because holding physical meetings is not always logistically possible, social media can help researchers build trust by allowing them to stay electronically connected and responsive (Koch, Gerber, and De Klerk Reference Koch, Gerber and De Klerk2018). Social media can allow community members to engage asynchronously with researchers through messaging and replying to posts. A social media page also can build trust by signaling project legitimacy through publicly verifiable academic credentials and friendships with community leaders.

However, in a socially connected world, networks can be a double-edged sword. Researchers should think carefully about who they are trying to reach through social media. As Côté (Reference Côté2013) wrote, bringing social media into research may compromise confidentiality, especially for vulnerable populations, such as people who are HIV positive, survivors of domestic violence, and immigrants. Researchers also should consider carefully how they use social media. Instead of providing a representative sample, social media instead may be more useful for reaching gatekeepers, who then can provide access to respondents (Marland and Esselment Reference Marland and Esselment2019). Researchers also should consider how social media might exacerbate problems of selection bias and social desirability (Bennetts et al. Reference Bennetts, Hokke, Crawford, Hackworth, Leach, Nguyen, Nicholson and Cooklin2019). Participants may self-select into the research or give responses they think researchers want.

In addition to building trust, researchers must demonstrate how their work benefits the community. The best way to do so is to align “research efforts with the priorities of key stakeholder groups” (Riffin et al. Reference Riffin, Kenien, Ghesquiere, Dorime, Villanueva, Gardner, Callahan, Capezuti and Reid2016, 218), who then will participate in anticipation of future benefits. Researchers also demonstrate benefits by providing concrete deliverables—that is, tangible research results that benefit the entire community. These deliverables create a positive feedback loop by building trust and reinforcing study legitimacy (Goldberg-Freeman et al. Reference Goldberg-Freeman, Kass, Gielen, Tracey, Bates-Hopkins and Farfel2010).

Broadly distributing results is a best practice for any CBR study, but it is especially helpful for longitudinal researchers (Goldberg-Freeman et al. Reference Goldberg-Freeman, Kass, Gielen, Tracey, Bates-Hopkins and Farfel2010; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Vogel, Goldberg-Freeman, Kass and Farfel2009). Social media provides a public record of relevant posts from the research project and disseminates deliverables in a way that benefits the maximum number of people. More than a static webpage on a university domain, which the public rarely will encounter, a social media presence engages the community where it is. However, researchers do not need to choose one over the other—a CBR project Facebook page can engage the community and link directly back to the more-academic university website.

By offering a low-cost, high-visibility method of community outreach, social media has the potential to facilitate community-based research studies and help researchers overcome some of the challenges associated with this type of work.

By offering a low-cost, high-visibility method of community outreach, social media has the potential to facilitate community-based research studies and help researchers overcome some of the challenges associated with this type of work.

USING SOCIAL MEDIA IN COMMUNITY-BASED RESEARCH: THE LITTLE ROCK CONGREGATIONS STUDY

In 2018, we introduced Facebook into a longitudinal community-based research (CBR) project: the Little Rock Congregations Study (LRCS). The LRCS involves students as multimethod researchers studying religion, politics, and community engagement among both clergy and congregants. The LRCS began in 2012, with multiple data-collection efforts since then. In each iteration of the study, we worked with community members and adjusted our methods and content. The 2018 LRCS focused only on clergy, and we introduced social media not as an experimental manipulation but rather as part of a broader strategy to recruit participants, build community relationships, and share our results.

We chose Facebook because it is the most popular social media site for US adults (Smith and Anderson Reference Smith and Anderson2018, 2) and because it is commonly used by religious congregations (Smietana Reference Smietana2018). We created a project Facebook page on September 10, 2018. We used Facebook to directly invite clergy to participate using the Messenger feature. We connected with the community by making posts, boosting posts, and tagging relevant congregations and individuals. Community members could follow our Facebook page and receive updates on data collection, community spotlights, and results. The community also could interact with the study and provide feedback through their reactions (i.e., likes, comments, and shares).

RESULTS

We evaluate the extent to which using Facebook helped us recruit participants, build relationships with the Little Rock community, and share the results of our study in the following subsections.

Recruiting Participants

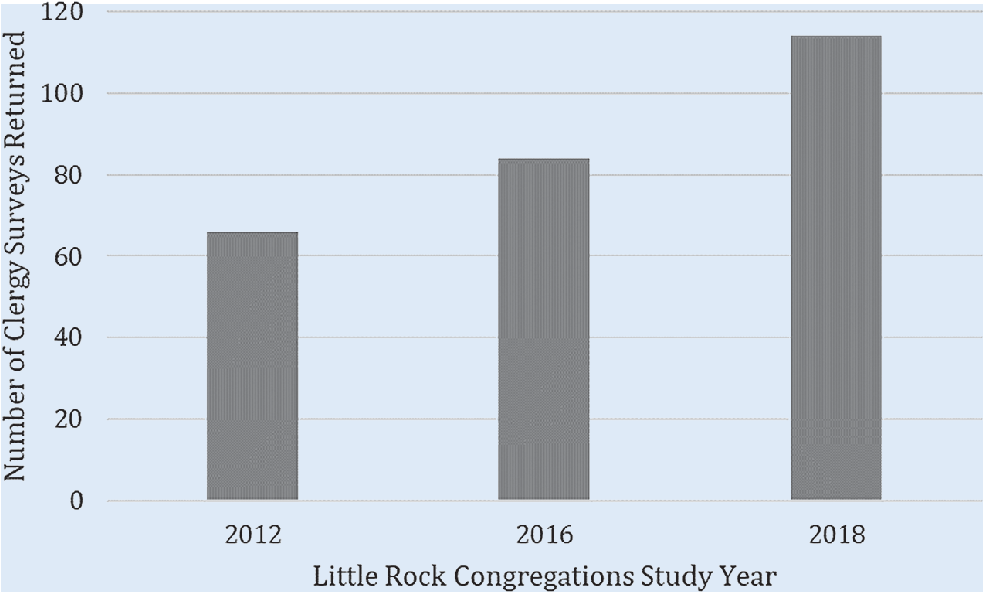

A main motivation for introducing social media into our CBR project was to recruit more participants and increase the response rate for our clergy survey. We expected that social media could help in at least two ways. First, the LRCS Facebook page provided additional credibility; it links to our university website where people could verify that we are neither partisan nor a business. Second, outreach through Facebook provided another point of personal contact with potential respondents (Bartholomew and Smith Reference Bartholomew and Smith2006; Dillman Reference Dillman2007). We evaluated the extent to which Facebook may have improved our response rates in 2018 by comparing prior data-collection efforts. (Full methodological details of the previous study iterations are in the online appendix.) Figure 1 summarizes the total number of clergy survey responses and the response rate over time.

Figure 1 Number of Clergy Surveys Returned and Response Rate over Time

When the LRCS first began in 2012, survey distribution to clergy was conducted entirely by mail, with reminders to participate via email and telephone calls. Surveys again were distributed by mail in 2016, with telephone and email reminders to participate, as well as Facebook Messenger reminders.

In 2018, the project moved to mixed-mode distribution, with electronic surveys sent via email (N=201) and Facebook (N=45). Facebook Messenger was the primary means of contact for 36 clergy members and a secondary means of contact for nine clergy members. Clergy that could not be reached electronically were contacted via mail (N=108). Reminders to participate were made via email, telephone calls, and handwritten letters. Professional telephone survey calls began about three weeks after the first contact. The overall response rate was 31.0%, with 66 surveys coming via email, 9 from mail, and 15 from telephone surveys. Twenty-three surveys were completed through Facebook Messenger direct links, resulting in a 51% response rate for the Facebook messages—well above the response rate for the study as a whole.

Figure 1 displays the improvement in the response rate over time. Overall, there was an upward trend as our research project built trust in the community and we moved to a mixed-mode survey distribution. This trend is discussed in more depth in the online appendix.

Building Better Community Relationships

We launched the LRCS Facebook page with the goal of improving our relationships in the community. Although Facebook data certainly encompass much more than social media interactions, what they can reveal is how many community members come into contact with our Facebook content, how many follow our page, how often they like our posts, and which posts they like the most.

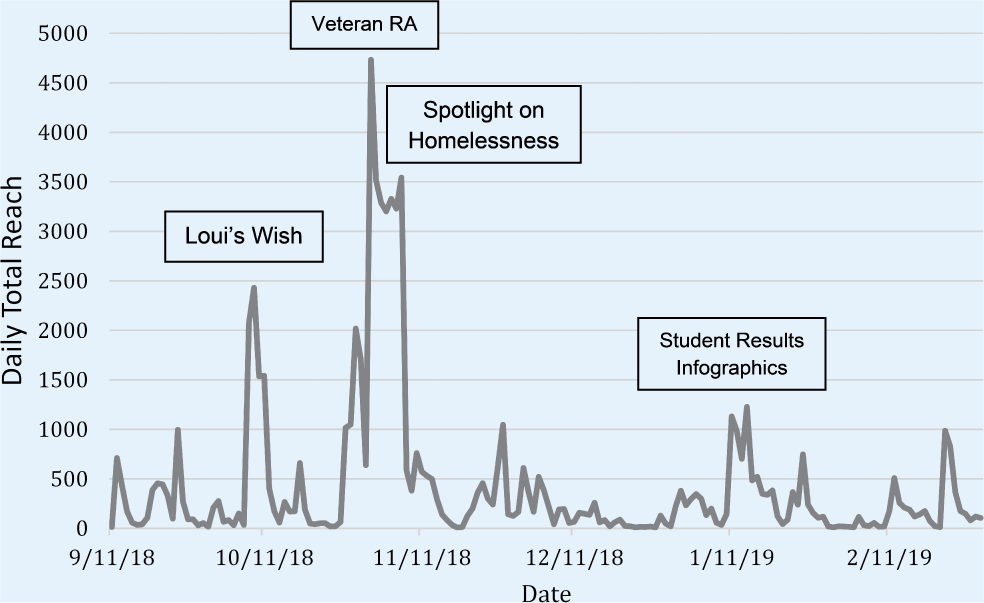

The LRCS Facebook page was launched on September 10, 2018; by March 1, 2019, we had 259 followers. Figure 2 shows the Daily Total Reach of our page during that period, defined by the internal metrics of our Facebook page as “The number of people who had any content from your Page or about your Page enter their screen. This includes posts, check-ins, ads, social information from people who interact with your Page and more (Unique Users).” Thus, not everyone who sees our posts necessarily follows the LRCS Facebook page. Because individuals share our posts and we pay Facebook to promote our posts, we can reach community members who are not following our page and likely are not aware of the CBR project. Figure 2 shows that not only were we reaching thousands of people but also which of our posts were reaching the greatest number of people. For all of our posts, we made decisions to highlight certain community issues, organizations, and congregations rather than others. We worked diligently to represent a variety of denominations, ethnicities, and causes; however, researchers should be aware of the potential for alienating—or at least signaling affiliation with—some segments of the community rather than others.

Figure 2 Daily Total Reach of the LRCS Facebook Page, September 10, 2018–March 1, 2019

Four points in figure 2 mark where our Total Daily Reach spiked. The first, labeled “Loui’s Wish,” was a post about a local church that worked with the Make-a-Wish Foundation to tell Loui, a terminally ill child in their congregation, that his wish to go to Disney World was granted. The second, labeled “Veteran RA,” was a post about a research assistant with the LRCS, Jordan Wallis. Jordan is a former Marine who researched veterans’ services that congregations provided. Many of his friends, family members, and people with whom he served shared this post and congratulated him, but certainly some of the people who read this post were outside of the Little Rock community.

The third label on figure 2 is “Spotlight on Homelessness.” This was a short blog post spotlighting the collaborative work that congregations in Little Rock are doing to fight homelessness through the nonprofit Family Promise. We believe that tagging participating congregations, as well as Family Promise, increased our post reach. The many likes and shares also helped us understand how important the issue of homelessness is to the people who follow our page. After winter break, we began sharing the best student-produced infographics on our Facebook page, which resulted in smaller spikes in our reach in January, represented by the fourth label, “Student Results Infographics.”

In reviewing the spikes identified in figure 2, it is important to note that they are all “boosted” posts. The LRCS received a small grant and spent $200 to “boost” posts or pay Facebook to place our posts in the feeds of people older than 18 living within 20 miles of Little Rock. Thus, one benefit of boosting posts is ensuring that they reach the target population. From September 10, 2018, to March 1, 2019, the LRCS made 97 posts and paid to boost 18 of them (i.e., an average of $11.11 per post). Overall, 35,719 people were reached through organic posts (i.e., 368.2 people per post) and 14,143 people were reached through paid posts (i.e., 785.7 people per post).

Through Facebook, we were able to come into contact with more community members than we otherwise would have. In 2017, we held a community event to present the findings of the 2016 LRCS. Although this event was attended by more than 200 community members and we considered it a success, our attendees were likely engaged with the findings for only a single day. With 259 followers, our Facebook page exceeds the attendance of that single event. By posting regularly, we can connect with the community more consistently. We have been able to reach tens of thousands of community members through our posts—far more than any event we could have held.

We have been able to reach tens of thousands of community members through our posts—far more than any event we could have held.

Of course, the effort it takes to like or share a post is far less than the effort it takes to attend an event. Our Facebook followers may be only marginally engaged with our research in the vein of “slacktivism.” Although there is little evidence to support a substitution effect of online for real-world activism (Christensen Reference Christensen2011), researchers may want to consider whether they would be trading depth of engagement for breadth by turning to social media. The increase in clergy survey participation is one indication that deep participation did not decline for our project.

Sharing Results

Distributing results is one key way to demonstrate that the work we are doing has meaningful benefits for the community. In 2012, we mailed executive reports to only the five congregation leaders with whom we did more extensive congregation-level data collection. In 2016, we emailed leaders (N=120) and distributed an estimated 200 executive reports at our community event.

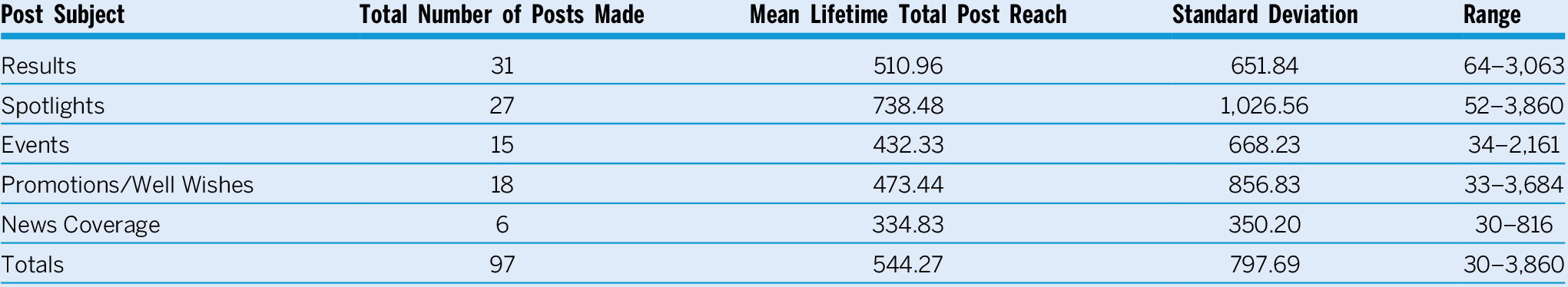

In 2018, we added a website as well as the LRCS Facebook page. The website (https://research.ualr.edu/lrcs) houses all of the findings from the study, including executive summaries, infographics, and academic papers—as well as blog posts discussing the findings—and community spotlights. We shared the 2018 executive summary on our Facebook page as well as various student-created infographics, highlights from the report, and data visuals. All of these posts fall into the “Results” category in table 1. Of all the posts we made through our Facebook page, these posts were the most common, followed by Spotlights posts, which highlighted the work of specific congregations in the Little Rock community. We also shared posts about events, news coverage of our research, and promotions to increase our followers. We carefully vetted our posts for tone and content that reflected the CBR project.

Table 1 Types of Posts and Their Reach through the LRCS Facebook Page, September 10, 2018–March 1, 2019

Spotlights posts garnered the highest mean lifetime post reach—that is, they reached the most people—likely because we tagged congregations mentioned in the posts and they often shared them. The reach of these posts varied widely, as indicated in the range data in the last column of table 1. Our Spotlights posts reached as few as 52 people and as many as 3,860 people.

Although the Results posts were not the most popular on our Facebook page, they did reach many people: 15,840 by March 1, 2019. When compared to the 200 people who received our executive summaries in 2016, this expanded reach appears well worth the social media–engagement effort. Certainly, all of these people did not read the report, but we can assume the same from those to whom we emailed and distributed paper copies in previous years. Even if only a small fraction of the expanded number of people we reached through Facebook engaged with our findings, this would be an improvement on previous efforts to distribute results.

CONCLUSION

CBR can improve the context and interpretation of findings, benefit research subjects, and improve validity. However, building trust with community members can be difficult and time-consuming. Social media is one way to bridge the gap between researchers and communities. The comparatively high response to the links sent via Facebook Messenger, the positive engagement with our posts on Facebook, and the increased overall response rate indicate that introducing social media into our CBR project had a positive impact. We were able to distribute results widely and have positive interactions with community members, including the following clergy review of our page: “I’ve participated in their survey before, and the questions about the congregations and leadership are fascinating. The information is extremely useful about how congregations are meeting the needs of the community.” Although this review was positive, social media is known to house trolls. We recommend responding promptly to negative comments and viewing them as an opportunity for professional engagement.

We believe Facebook worked particularly well for our longitudinal project because we were recruiting clergy members, not the general public, as participants and because congregations often are active on Facebook. Other social media platforms may work better for other projects; therefore, researchers should consider carefully their goals and their study populations. Although social media can help community-based researchers, it should not take the place of personal relationships.

Although social media can help community-based researchers, it should not take the place of personal relationships.

Our research team views social media as a supplement to other community-engaged research tactics, not a replacement for them. We believe that one reason our Facebook page was successful is that we already had spent years building relationships in the community. Researchers starting from scratch may find that using social media to facilitate community-based research is more challenging; however, posting helpful results and being responsive to comments indicates to community members that their participation will have benefits. Although CBR can be difficult, social media can help researchers overcome the challenges, and the results are often well worth the effort.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1049096520001705.