Introduction

Spatial theory is one of the most influential approaches for understanding party competition and voting behaviour (e.g., Adams et al., Reference Adams, Merrill and Grofman2005; Downs, Reference Downs1957). To test the implications of this theory, which assumes that parties and voters take positions in a common political space, scholars require estimates of the positions of parties on some dimensions. Furthermore, to account for the possibility that party competition is multidimensional (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Koedam, Reference Koedam2022), scholars ideally have information about parties’ positions on multiple ideological divides. Different strategies can be used to obtain said estimates, but one of the most common approaches is to ask experts to place parties on different ideological scales.

Previous work has shown that expert surveys provide estimates of parties’ ideological positions that correlate strongly with estimates from other sources, such as voter perceptionsFootnote 1, party platforms or estimates from projects developing Voting Advice Applications (VAA) (Bakker and Hobolt, Reference Bakker, Hobolt, Evans and De Graaf2013; Dalton and McAllister, Reference Dalton and McAllister2015; Ferreira da Silva et al., Reference Ferreira da Silva, Reiljan, Cicchi, Trechsel and Garzia2023).Footnote 2 While other approaches thus provide estimates that are equivalent to those obtained from expert surveys, the latter have a number of distinct advantages, explaining their wide use in the field. Specifically, expert surveys are comparatively inexpensive (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Bakker, Brigevich, De Vries, Edwards, Marks, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2010), can be administered quickly and can include items on more abstract dimensions and issues than what is common in voter surveys.

The Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) has been collecting information on parties’ ideological positions in Europe since 1999 (Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022), providing scholars with estimates that have been used to describe the dimensionality of party systems in Europe (Rovny and Edwards, Reference Rovny and Edwards2012) and the dynamics of party competition over issues (Koedam, Reference Koedam2022; Rovny, Reference Rovny2012). The data have also been combined with individual-level survey data to examine the links between party positions and vote choice (De Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012) or between the party system and voting behaviour (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Jolly, Polk, Hobolt and Rodon2021).

The CHES project originally focused on European party systems, but in recent years, the team has expanded its geographical coverage to Latin America, Australia, and Israel. These expansions not only imply that researchers interested in party competition in these countries now have access to estimates of parties’ positions in these settings, but they also create opportunities for comparative research into the structure of party competition across regions (Martínez-Gallardo et al., Reference Martínez-Gallardo, de la Cerda, Hartlyn, Hooghe, Marks and Bakker2023).

Here, we present the data from a new addition to the project: CHES Canada. This research note serves two goals. First, to introduce original data from an expert survey on the ideological positions of political parties in Canada—including the main federal parties as well as provincial parties in Ontario and Quebec. Second, to provide an initial comparative evaluation of the Canadian party system to that of other multiparty and multidimensional European democracies.

Data Collection and Measures

By searching websites of political science and government departments across Canadian universities, we compiled a list of 99 academicsFootnote 3 with an interest in Canadian politics, party politics and elections. These experts received an email invitation to the survey about Canadian parties, offered in English and French.Footnote 4 At the end of the survey, the experts were asked if they had expertise in Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario or Quebec politics and would like to fill out a shorter version of the questionnaire focused on provincial parties. A total of 44 experts participated in the main survey. We also received a sufficient number of responses from experts in Ontario (10) and Quebec (14) to release expert estimates of parties’ positions in these provinces.Footnote 5 The data were collected between 5 December 2022 and 20 January 2023, with the survey asking experts to indicate parties’ “current” positions.

The survey largely followed the structure of 2019 CHES-Europe, including questions about the positions of parties on economic issues, postmaterialism, overall ideology (left-right) and a host of specific issues, among others immigration, taxes and rural/urban interests (see Appendix A for the full list of items included). In addition to a measure about parties’ positions on enforcing public health measures (taken from a CHES-Europe COVID survey), we added two issues to the survey that we thought were particularly salient in the Canadian context: decentralization to provinces and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. For all the dimensions and issues, experts were asked to rate parties on a 0–10 scale.

For the main ideological dimensions (economic issues and postmaterialism), as well as a select number of issues, experts were also asked to indicate to what extent they thought each party blurs its positions on the dimension, how divided it is on the dimension, and how salient the dimension is for a party. Finally, the survey asked about a number of party characteristics (see Appendix A for details).

The provincial surveys were substantially shorter, and only included questions about the main ideological dimensions. Appendix A lists all the questions that were included in the survey and details the answer options.

After processing and cleaning the data, we aggregated experts’ responses to obtain a party-level dataset with averaged estimates of parties’ positions on the different ideological and issue dimensions, as well as their characteristics. For the main ideological dimensions, the dataset also includes the standard deviation of experts’ placements of a party.Footnote 6, Footnote 7

The Canadian Political Space

Using the CHES Canada dataset, we can describe the structure of party competition in Canadian politics. Here, we focus on parties’ positions on the two main ideological dimensions: economic left-right and positions on postmaterialist issues. In line with earlier work, we refer to the latter as the GAL-TAN dimension (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022).Footnote 8 Figure 1 illustrates where experts position the parties in this two-dimensional space, with federal parties shown as circles.Footnote 9 The experts distinguish between two main blocs of parties. A first bloc of parties includes the Conservative Party of Canada (CPC) and the People's Party of Canada (PPC). These parties are positioned economically to the right and take more traditional positions on the GAL-TAN dimension. All other federal parties are positioned economically to the left while taking more liberal positions on the GAL-TAN dimension—with the Bloc Québécois (BQ) being slightly more centrist. Within each bloc, economic left-right is the main dimension distinguishing between parties. In particular, the New Democratic Party (NDP), the Green Party (GPC) and the Liberal Party (LPC) all take similar positions on the GAL-TAN dimension but differ in terms of their economic positions. It is noteworthy that, as is common in many European party systems as well (e.g., Lefkofridi et al., Reference Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann2014), the parties are aligned along a diagonal structure, leaving the left-TAN and right-GAL quadrants empty.

Figure 1. Positions of Federal and Provincial Parties on the Economic Left-Right and GAL-TAN Dimensions.

Figure 1 also shows the positions of parties in Ontario (diamonds) and Quebec (triangles) in this two-dimensional space. A comparison of party positions in both settings clarifies that the party system structure differs substantially between provinces. The Ontarian party system resembles the offer at the federal level most strongly, a finding that is consistent with the fact that there are strong organizational connections between the federal parties and the provincial parties in Ontario (Pruysers, Reference Pruysers2014). Figure 1 shows that party competition differs in Quebec, notably because the space includes parties that combine economically right-wing with culturally progressive positions. Furthermore, Figure 1 shows that parties in Quebec have more distinct profiles than Ontarian or federal parties, given the absence of clear ideological blocs.

Applications

The previous section illustrates how the CHES Canada data can be used to describe the structure of party competition at the federal and provincial level. Figure 1 did so with a focus on the two main ideological dimensions, but this analysis can be extended to a large number of included issue dimensions. Below, we present two initial applications, one using individual-level and one using comparative party-level data.

First, the data can be combined with individual-level survey data from the Canadian Election Study or provincial election studies. By doing so, scholars can, for example, assess whether the positions of parties on specific issue dimensions broadly match the preferences of their electorates on these issues. By matching individual-level survey data and CHES estimates, researchers can get a sense of how ideologically sorted voters are. To illustrate this approach, we use data from the 2021 Canadian Election Study (CES; Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Harell, Rubenson and Loewen2022) to obtain estimates of the policy preferences of voters of the main parties on income redistribution. The CES asked respondents “How much do you think should be done to reduce the income gap between the rich and the poor?”, with answers ranging from much more (= 1) to much less (= 5). This measure of voters’ positions on income redistribution can be matched with the CHES estimates of parties’ positions on redistribution (coded so 0 = strongly favours redistribution, 10 = strongly opposes redistribution). Combining both types of data, we find that voters’ average preferences on the need to reduce the income gap maps well onto parties’ positions on the issue of redistribution (Pearson correlation of 0.99). This implies that Canadian voters are effectively sorted into parties based on their opinion on this issue (for more details, see Appendix B).

Second, given that the CHES Canada questionnaire is similar to earlier CHES surveys, the data can easily be merged with CHES data from other countries and regions of the world. For example, scholars can evaluate how polarized or multidimensional the Canadian party system is compared to other countries. To illustrate the potential of combining data from different CHES modules, we merge the CHES Canada data with those from the most recent CHES-Europe wave (2019).

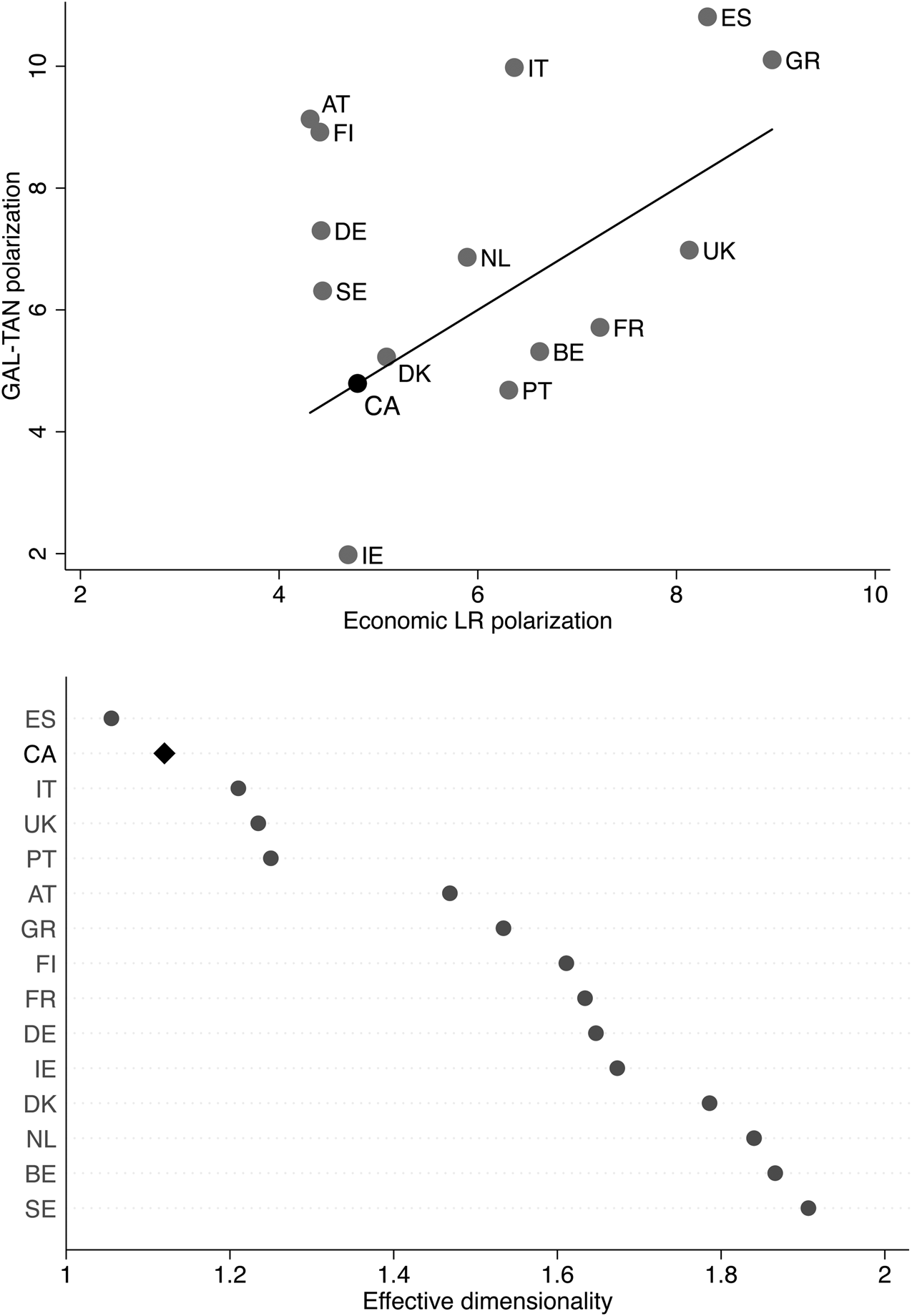

The top panel of Figure 2 plots each country by its level of party polarization on the economic left-right (x-axis) and the GAL-TAN dimension (y-axis).Footnote 10 A few observations stand out. First, from a comparative perspective, the Canadian party system is not particularly polarized. On both dimensions, but especially with regard to GAL-TAN issues, it mirrors the least polarized democracies in Western Europe. Second, the Canadian party system falls on the diagonal line, which represents a context in which the two ideological dimensions are equally polarized. This may suggest that the two dimensions are strongly correlated, with the same party oppositions playing out on both sets of issues.

Figure 2. Canadian Party Polarization and Dimensionality in Comparative Perspective.

Indeed, as already suggested by Figure 1, the bottom panel of Figure 2 confirms the relatively one-dimensional structure of Canadian party conflict. Using the effective dimensionality (ED), a measure that captures the relationship between the different dimensions of a political space, we observe that economic left-right and GAL-TAN virtually collapse into a single ideological conflict with an ED close to 1 (for the exact operationalization, see Koedam et al. Reference Koedam, Binding and Steenbergen2024). This structure is similar to that of the United Kingdom, but in stark contrast to the more complex and two-dimensional party systems of, among others, Sweden, Belgium and the Netherlands. This may hint at the role of political institutions, such as the electoral system. Future research can unpack this further.

Conclusions

The CHES Canada dataset is the newest extension of the CHES project. We surveyed Canadian experts about their perceptions of parties’ positions on the main ideological dimensions, specific issues and asked them to rate parties on a number of indicators of the parties’ characteristics. We plan to continue CHES Canada in the future, collecting data at regular time intervals. In doing so, we aim to be in sync with the CHES-Europe waves (i.e., every four to five years).

CHES Canada data can be used by students of party politics in Canada to describe party competition between federal parties and provincial parties in Ontario and Quebec. Furthermore, given that CHES Canada is part of a large comparative project and thanks to the inclusion of identical questions and measurement instruments across countries, the CHES Canada dataset allows scholars to conduct comparative analyses to assess the similarities and differences between the Canadian party system and the political space in other democratic settings. The applications that we presented and illustrated in this note offer a glimpse of the many potential ways in which the data can be used by both Canadianists and comparativists.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423924000337.

Data Availability statement

The full dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YV8CMR. All CHES data from different regions and CHES waves can be retrieved from https://www.chesdata.eu/.

Acknowledgements

Jelle Koedam acknowledges funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF Ambizione Grant, No. 216463). We thank Nadjim Frechet and Patrick Fournier for assistance with the translation of the survey to French and for helpful suggestions for the survey instrument, as well as Garret Binding for data assistance. We also want to thank all experts who participated in CHES Canada. Finally, we are grateful to the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.