Introduction

People who sustain an acquired brain injury (ABI) often experience long-term effects, including physical, cognitive, emotional, mood and behavioural changes, that can impact social functioning, activities of daily living, financial status, and employment opportunities (Brasure et al., Reference Brasure, Lamberty, Sayer, Nelson, Macdonald, Ouellette and Wilt2013; Hooson, Coetzer, Stew & Moore, Reference Hooson, Coetzer, Stew and Moore2013; Humphreys, Wood, Phillips & Macey, Reference Humphreys, Wood, Phillips and Macey2013; Ponsford, Sloan & Snow, Reference Ponsford, Sloan and Snow2013; Powell et al., Reference Powell, Glang, Pinkelman, Albin, Harwick, Ettel and Wild2015). In Australia, people with ABI continue to experience low work rates (30%), with employment lower than other people with disability (48%) and the national average (79%) (ABS, 2018; AIHW, 2019, NDIS, 2019). A study comparing a sample of people with ABI with a normative sample matched on key demographic variables (including age, gender, living location, living situation), found that the ABI group were four times more likely to experience reduced economic participation, despite the fact that prior to their injury they had worked full-time (Migliorini, Enticott, Callaway, Moore & Willer, Reference Migliorini, Enticott, Callaway, Moore and Willer2016).

For a person with ABI, returning to work has been identified as an important stage in rehabilitation, and is central to improved quality of life in the long term (Cullen, Chundamala, Bayley & Jutai, Reference Cullen, Chundamala, Bayley and Jutai2007; Willer & Corrigan, Reference Willer and Corrigan1994). However, very little research has been published on the economic impacts, efficacy or costs of vocational rehabilitation, and those that do exist are most often with early post-injury groups (Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, Wood, Phillips and Macey2013; Radford et al, Reference Radford, Sutton, Sach, Holmes, Watkins and Forshaw2018). One of the few recent economic evaluations available aimed to determine whether specialist vocational rehabilitation intervention was more effective at work return and retention 12 months after brain injury than usual care, whilst also exploring feasibility of collecting economic data (Radford et al., Reference Radford, Phillips, Drummond, Sach, Walker and Tyerman2013). This research, conducted with 94 people with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in the United Kingdom, found more vocational rehabilitation participants (15%) were working than those receiving usual care, with the mean vocational rehabilitation health costs per person £75 greater at 1 year. The study informed a protocol for a multicentre, randomised controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of early, specialist vocational rehabilitation plus usual care, compared with usual care alone, on work retention 12 months post-TBI; however, whilst the authors found it was feasible to assess the cost-effectiveness of vocational rehabilitation, target recruitment for this trial was not reached (Radford et al., Reference Radford, Sutton, Sach, Holmes, Watkins and Forshaw2018).

In other neurotrauma cohorts, individualised and supported employment transition has been identified as an effective vocational rehabilitation approach; however, the intensity of the customised support required has shown it may not be cost-effective at standard willingness to pay thresholds (Sutton, Ottomanelli, Njoh, Barnett & Goetz, Reference Sutton, Ottomanelli, Njoh, Barnett and Goetz2020). Aligned with this, in the field of ABI, the importance of economic evaluations capturing start up expenditure associated with employment programmes has been identified, as has an expectation that emerging programmes may incur higher costs in the initial stages (Radford et al., Reference Radford, Sutton, Sach, Holmes, Watkins and Forshaw2018). Following, an understanding of the differing responses to vocational rehabilitation based on time post-injury – with focus beyond early intervention to those living with their injury for longer – is necessary (Wehman et al., Reference Wehman, Kregel, Keyser-Marcus, Sherron-Targett, Campbell, West and Cifu2003).

In addition to the brain injury impacts, external factors that influence vocational outcomes have been frequently identified to relate to the employer. These include whether prospective employers understand the impact of an ABI and are able to offer appropriate levels of support in the workplace; the willingness of employers to make appropriate modifications and adjustments; the level of employer confidence and capability in the area of disability inclusion; and the existence, accessibility and skill of providers to deliver effective and tailored support for people with cognitive behaviour support needs in the workplace (Alves et al., Reference Alves, Nilsen, Fure, Howe, Løvstad and Fink2020; Dahm & Ponsford, Reference Dahm and Ponsford2015; Howe et al., Reference Howe, Andelic, Perrin, Røe, Sigurdardottir and Arango-Lasprilla2018; Libeson, Downing, Ross & Ponsford, Reference Libeson, Downing, Ross and Ponsford2020). In addition, there are limited options to support and prepare a person with an ABI to become ‘work ready’ if they have been out of the workforce for a significant period of time. More broadly, retraining work can be a challenging proposition for someone with new learning difficulties as a result of cognitive behavioural changes, and it requires individualised approaches that include a mix of skill building supports, employer and co-worker education, reasonable adjustments and well-defined work tasks (Australian Network on Disability, 2018; Gentry, Kriner, Sima, McDonough & Wehman, Reference Gentry, Kriner, Sima, McDonough and Wehman2015; Waterhouse, Kimberley, Jonas & Glover, Reference Waterhouse, Kimberley, Jonas and Glover2010; Weaver, Reference Weaver2015).

In Australia, disability reform, including a focused effort on growing the economic participation of people with disability, is happening at a State and National level. The National Disability Strategy was a 10-year national plan (2010–2020) with a vision to ‘foster an inclusive society that enables people with disability to fulfil their potential as equal citizens’ (Department of Social Services, 2010, p. 22) and has included key policy action areas focused on economic security and employment (NDIS, 2019). Although a new plan has not yet been released, in December 2020 Disability Ministers from across Australia issued a Statement of Continued Commitment to the Strategy (Department of Social Services, 2020). More recently, the Australian Government released a Disability Employment Strategy (Commonwealth of Australia, 2020). This Strategy recognises a need to drive change and innovation to address barriers to work for people with disability, and aligns with both the National Disability Strategy and the Government’s commitment to uphold the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which recognises ‘the right of persons with disabilities to work, on an equal basis with others [including] the right to the opportunity to gain a living by work freely chosen or accepted in a labour market and work environment that is open, inclusive and accessible to persons with disabilities’ (United Nations, 2006, Article 27).

Although the Disability Employment Strategy is a major strategic reform, there remains a need to address barriers to work for people with ABI, who typically have poorer open employment outcomes. It is well recognised that return to work approaches following ABI need to be tailored to the individual circumstances, opportunities and support needs of each person (McRae, Hallab & Simpson, Reference McRae, Hallab and Simpson2016). However, there has to date been limited evaluation of efficacy or the most effective elements of return to work programmes, or workplace factors that may relate to work retention, for people with ABI (Alves et al., Reference Alves, Nilsen, Fure, Howe, Løvstad and Fink2020; Ponsford et al., Reference Ponsford, Sloan and Snow2013). Recently in Australia (Bould & Callaway, Reference Bould and Callaway2021) used a co-design approach with people with ABI, employers providing work for people with ABI and social and injury insurers funding employment services, to identify enablers and barriers to open employment following ABI, and strategies to ensure access to and sustainability of mainstream employment. This helped guide the development of a new pathway to mainstream employment, tailored for people with ABI, called ‘Employment CoLab’.

Employment CoLab aligns with recommendations from existing research, including the importance of: (1) a collaborative team approach, tailored to the person with ABI and the employer, with attention paid to the workplace, employer and work colleagues (Donker-Cools, Daams, Wind & Frings-Dresen, Reference Donker-Cools, Daams, Wind and Frings-Dresen2016; McRae et al., Reference McRae, Hallab and Simpson2016; van Velzen et al., Reference van Velzen, van Bennekom, van Dormolen, Sluiter and Frings-Dresen2011); (2) support to disclose a person’s ABI to the employer (Piccenna et al., Reference Piccenna, Pattuwage, Romero, Lewis, Gruen and Bragge2015); (3) identification of modifiable workplace practices that may aid employee performance (Alves et al., Reference Alves, Nilsen, Fure, Howe, Løvstad and Fink2020); (4) return to work plan of work tasks, job coach and coping strategies (Ntsiea, Van Aswegen, Lord & Olorunju, Reference Ntsiea, Van Aswegen, Lord and Olorunju2014); (5) pre-vocational skills training for the employee with ABI (Powell et al., Reference Powell, Glang, Pinkelman, Albin, Harwick, Ettel and Wild2015; Steel, Buchanan, Layton & Wilson, Reference Steel, Buchanan, Layton and Wilson2017); (6) work trial, and on-the-job training (Piccenna et al., Reference Piccenna, Pattuwage, Romero, Lewis, Gruen and Bragge2015; Willer & Corrigan, Reference Willer and Corrigan1994); and (7) ongoing episodic/intermittent support for the employee with ABI, the employer and/or work colleagues as required (Bond, Reference Bond2004; Hart et al., Reference Hart, Dijkers, Whyte, Braden, Trott and Fraser2010), and for the lifetime of the role (Willer & Corrigan, Reference Willer and Corrigan1994).

This paper details a pilot and evaluation of Employment CoLab undertaken in collaboration with a vocational rehabilitation specialist service in Melbourne, Victoria, with one of their employees assigned to the role of CoLab consultant. The aim was to: (1) test the capacity of the pathway to improve employment outcomes for people with ABI; (2) document the benefits and key learnings for pathway refinement, replication and scaling for use; and (3) undertake an exploratory economic evaluation to examine the cost to the injury insurance funder for Employment CoLab, compared to traditional employment pathways.

Method

Design

The pilot of Employment CoLab was conducted between May 2019 and December 2020. A mixed methods evaluation was conducted, and data reported in this paper are drawn from individual interviews collected between May 2019 and February 2021, and an explorative economic evaluation. Ethical approval for the study was gained from Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee. Written consent was obtained from all participants.

Employment settings

The first component of Employment CoLab is ‘Engagement of the Employer’. Employers were identified using three methods: (1) key professional contacts of the authors, the vocational rehabilitation specialist, or the funding organisations; (2) advertisements on job search websites (e.g. SEEK); and (3) cold calling employers’ following a review of their website that mentioned an interest in workplace diversity. A total of 18 employers were engaged in phone conversations with either the authors or an employee from the vocational rehabilitation specialist service. Of these, seven agreed to have a face-to-face meeting to identify and document their business and human resource needs. One or more roles were subsequently identified with six of these employers The roles were in three industry categories, as defined by the Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZSIC) (ABS, 2020): (1) administrative and support services (n = 4); (2) accommodation and food services (n = 1); and (3) traffic management (n = 1).

Once an employer was engaged, the second component of Employment CoLab involved either the authors or the vocational rehabilitation specialist working with each employer to create a pictorial position description detailing the tasks involved in that role, and details of flexible work arrangements (e.g. working hours; consideration of job share). This input was provided via case-based funding from the injury or disability insurer. Following, the third component was ‘Recruitment’ which involved sourcing suitable candidates who have been assessed as: (1) having a goal relating to work; (2) work ready or near work ready; and (3) hold interests matched to the role.

Participants

Purposive sampling was used with participants recruited from four key groups; (1) employees with ABI who had gained employment via Employment CoLab; (2) employers and co-workers; (3) allied health professionals / vocational providers (working with employees on employment transition); and (4) injury insurance funders who hold portfolio responsibility for disability employment.

A total of seven people with ABI gained employment via the pathway over a total 18-month pilot period; of whom five (2 females and 3 males) provided consent to participate in a brief survey, and two individual interviews, and three (1 female and 2 males) also consented to participate in the economic evaluation. All five were a minimum of 4 years post-injury, had a dual diagnosis (e.g. ABI plus a mental health diagnosis or physical health condition). They were all employed in flexible work arrangements (i.e. part-time or casual work), with a tailored approach to return to work that included the identification and addressing of modifiable workplace factors (i.e. evaluation of working tasks; environment; job coaching, advice on coping strategies, and application of cognitive aids including assistive technology) to aid performance, and a gradual increase of work hours as work tolerance and employer and/or employee confidence increased. Across these five employees, three employers/co-workers, four allied health professionals/vocational providers; and five employees from injury insurance funders consented to participate in a brief survey and an individual interview. Details of the participants are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Participant Demographics

Matched sample

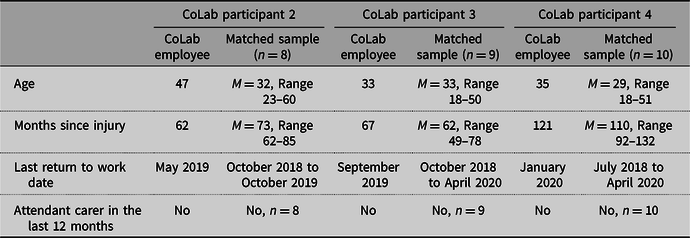

For the explorative economic evaluation, via an administrative database of the injury insurance funder, the three employees with ABI who had gained employment via Employment CoLab and consented to participation in the economic evaluation were matched on key characteristics to eight to 10 de-identified insurance claimants (see Table 2).

Table 2. Demographic, Injury and Return to Work Data for the Three CoLab Participants and the Matched Sample

Procedure

People with ABI who had gained employment via the Employment CoLab pathway were invited to complete a brief survey to obtain demographic data (i.e. gender, age, time since injury), and individual interviews at two time points: 1–4 weeks after gaining employment via the pathway, and 6–9 months after commencing employment. Once consent was received from employees with ABI, their employers/co-workers, allied health professionals/vocational providers, and injury insurance funders were invited to complete a brief demographic survey, and participate in an individual interview, which occurred four to 11 months after the employee commenced employment.

Interviews were held in 2020–2021 at a location chosen by each participant, either at their home or workplace. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, all interviews were conducted via phone or a videolink platform. Interviews were conducted by the first author, using a schedule of prepared open-ended questions and prompts to elicit more detailed information. The first interview for employees with ABI covered topics about experience of work before and after their ABI, roles and routines in a typical day, thoughts on being unemployed and the help and support they receive on a day-to-day basis. The interview following commencement of employment for all participant groups covered topics about the support received through the pathway, whether the support has been helpful or not, and anything they did not like or thought could be improved. Interviews lasted between 20 and 50 min, were digitally recorded with permission and subsequently transcribed verbatim, and each participant was assigned a participant number to ensure anonymity.

The explorative economic evaluation is presented as a cost-analysis from an insurers perspective; full details in accordance with the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) checklist (Husereau et al., Reference Husereau, Drummond, Stavros, Carswell, Moher and Greenberg2013) are available from the authors on reasonable request. Insurer costs were obtained from the insurance administrative database for the three employees with ABI who utilised CoLab and these were compared to a matched sample who utilised the traditional employment pathways. Costs included administration, hospital, income, legal, long-term care, medical and para-medical costs (including allied health and vocational costs). The time horizon included the 3 years prior to employment and the 6 months following employment (42 months in total). All costs over the 42 months were included to give context to the depth of resources utilised by the participants over a longer time horizon. The rational for including all costs over this time horizon was: (1) many participants had a complex history of unsuccessful employment attempts prior to the successful employment; and (2) there are a number of other services which may have contributed to vocational support, for example allied health interventions such as occupational therapy, speech therapy and physiotherapy. While all costs are presented for the 42 months; the isolated vocational costs are presented for the full 42 months as well as just for the final 6 months. Average hours of work per week are also reported noting the remuneration was not available. All data was inflated by applying the Consumer Price Index (ABS, 2021) to represent $AUD 2019/20.

Analyses

The demographic survey data were entered into SPSS Statistics 21 and analysed using descriptive statistics. SPSS Statistics 21 was also used for the economic evaluation analyses. The matched sample was compiled by comparing the three CoLab employees to 27 de-identified clients of the injury insurance funder who had gained employment via traditional employment pathways (i.e. Disability Employment Service (DES) providers). The resultant samples were matched on an accident date ± 2 years, absence of attendant carers in the last 12 months, and being in employment during 2018–2019 or 2019–2020. Other matching criteria were removed due to low yield. For example, age was initially matched within a 10-year age bracket, but was revised to be any age to enable more matches, as complete data sets were required for inclusion in the analysis. Costs and hours of work were reported as a mean value with a standard deviation. Independent t-tests were used to calculate the between group mean difference with 95% confidence intervals; significance assumed at p < 0.05.

The qualitative data analyses were guided by Patton’s (Reference Patton2015) reflexive enquiry framework, which was used in two ways. Firstly, it was used to aid triangulation of data sources and increase rigour in the qualitative data analysis. This included consideration of both each research participant’s unique perspectives (i.e. employees with ABI, employers, vocational specialists) as well as the researcher’s perspectives, and was undertaken via documentation of field notes during each interview; and by the researcher’s reflective journaling following each interview. Following, reflection was used within a total of four telephone or videolink sessions undertaken by the first author (who has a background in psychology) and the vocational providers engaging with potential employers and candidates with ABI, with the researcher taking field notes during these reflective practice sessions and consensus key learnings identified (Patton, Reference Patton2015).

A comparative method of content analysis was undertaken with the interview data, reflexive field notes and journal entries, and written notes from the four reflection sessions, using a fifteen-point checklist for thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Firstly, the researcher read each transcript and noted items of potential interest, with single words or brief phrases from the qualitative data used to name codes and identify themes (Clarke & Braun, Reference Clarke and Braun2013). Secondly, an iterative process was followed, with the first author re-reading each transcript, to develop a deeper understanding of the data and ensure the identified themes and sub-themes were representative of the data. To further aid methodological rigour, peer checking of identified themes was undertaken with the second author (Krefting, Reference Krefting1991).

Results

Reflective learnings

There were two keys learnings from engaging with employers and recruiting candidates with ABI: (1) building collaborations with businesses is time consuming and not easy; and (2) identifying industry need and carving out a role without specific candidates in mind does not always equate to employee engagement.

Building collaborations with businesses is time consuming and not easy

Some employers did not return phone calls, or respond to a follow-up email, and one pattern that emerged when speaking to employers who said they were open to diversifying was the question of what financial incentive was going to be offered and for how long. Although it is possible for social and injury insurance funders to offer a paid work trial for clients with ABI, this was not discussed in initial conversations, as an important component of Employment CoLab was identifying an employer need for a paid role, and ensuring there was budget available to sustain the identified role.

Time was another factor, as employers in need of staff sometimes wanted to move quickly, and did not want to take on a person that required training, or needed additional support. For example, one employer wanted someone who was ready to go immediately, and did not think a person with ABI would fit in as a typical employee would. A few employers commented they were open to diversifying their workforce, but to be suitable for the role wanted the person to meet particular criteria. Often, their requirements involved working full-time, and/or a need to pass a medical examination.

There were also a couple of employers who spoke about risk protocols, and from their comments it appeared that they viewed employing a person with ABI as too big a risk for their business. For example, one employer said they did not have any suitable roles as there were too many hazardous areas for a person with ABI.

Identifying industry need and carving out a role without specific candidates in mind does not always equate to employee engagement

For two of the employers (in the category of administrative and support services, ABS, 2020) the identified roles were not able to be filled by a person with ABI. The type of role and requirements of the role (e.g. driver’s license, physical tasks, hours and location) impacted on whether a person might consider a role. Furthermore, the vocational rehabilitation specialist (CoLab Consultant) found that when speaking with people who were job ready or nearing being job ready, they had identified specific job interests and it was difficult to persuade them to try something else. For some people low confidence and anxiety led to concerns even with a supported model, and they did not want to consider the role.

Results from the thematic analysis of the qualitative interviews

As illustrated in Table 3, across the participant groups four major themes were identified, two of which comprised sub-themes: (1) valuing employment and diversity; (2) Barriers to mainstream employment; (3) Reflections on being employed; and (4) Being supported. The themes and sub-themes, are discussed individually below, with participant quotations to illustrate the main points.

Table 3. Themes and Sub-themes Identified by Participant Group

Valuing employment and diversity

All participant groups discussed the value of employment. Participants with ABI recalled how they missed working and were eager to get back to work, saying for example, ‘I miss working, I just want to have something to do, get out of the house. I like the social aspect to work, you know someone to talk to, something to do’ [Participant 3 with ABI]. Employers and co-workers also spoke about wanting to facilitate employment for people with ABI, and recognised the value of ensuring diversity in their staff. They said for example, ‘I understand the challenges for people with ABI re-engaging with the workforce, so it was great to have the opportunity to try and facilitate that. I personally also think it’s good to have diversity in the staff’ [Employer 1].

Barriers to mainstream employment

As the employer participant above hinted to, prior to Employment CoLab, the participants with ABI had experienced a range of barriers re-engaging with the workforce. Participants with ABI, allied health professionals/vocational providers, and funders identified difficulties first of all in finding employment, and then to maintain the work they did find. They said for example:

We have really motivated clients but it is really hard to find employers that are willing to be flexible and give that extra attention. I think there is a lot of good intention out there, but employers don’t know how to support someone with a disability, that’s where we often fall down [Funder 5].

This theme comprises two sub-themes: lack of understanding about disability, and discriminatory attitudes relating to ABI.

Lack of understanding about disability. The most common obstacle participants with ABI, allied health professionals / vocational providers and funders talked about, was finding employers who had a good understanding of ABI. Common issues were their skills being undervalued, and employers not modifying or accommodating someone with a disability in the workplace. Participants said for example, ‘Employers are understanding, but they’re hesitant, you know, why go for the disabled guy when there is someone who is able to do those few more hours and maybe at a quicker pace’ [Participant 3 with ABI]; and, ‘I think it’s incredibly challenging for people with disability to find work…generally I think that their skills are undervalued, potentially because employers aren’t sure how to modify or accommodate someone with a disability in the workplace’ [Allied health professional / vocational provider 2].

Some participants with ABI had prior assistance from a vocational provider (sometimes referred to as ‘voc provider’ by participants). However, they expressed frustration with the competence of staff, suggesting the formal assistance offered had not been useful in finding employment. They said,

A large portion of my week was spent looking for work, I really wanted to work, but I didn’t know how to go about it, and I felt like I had been given up on by the voc provider. There was a lack of opportunities, and certainly a lot of frustration, a lot of angst and that was the case for a very long time [Participant 4 with ABI].

Whilst some participants with ABI had found volunteering roles, or had been offered work in supported employment, they struggled to find mainstream employment, saying for example,

Often people can find volunteering roles, or work in supported employment, so if you have a client who ultimately wants open employment it is very hard for them to see themselves in supported employment. I have had clients who don’t want to categorise themselves as a person with a disability. But finding employment in the open market isn’t easy. Employers often see too many safety risk protocols, it’s in the too hard basket. I think that comes from a lack of understanding of ABI and generalisation [Allied health professional / vocational provider 4].

Discriminatory attitudes relating to ABI. Participants with ABI, capacity-building supports and funders described the discriminatory attitudes they had previously encountered from employers when disclosing their disability to employers. They said for example, ‘I have got jobs in the past, but it seems like I have got fired as soon as they found out that I have a brain injury’ [Participant 4 with ABI]; and, ‘Some people fear disclosing their ABI, because they have had a bad experience beforehand of disclosing and it shutting the door’ [Allied health professional / vocational provider 4].

Allied health professionals / vocational providers and funders also spoke about the challenge of not disclosing, seeing both positive and negative implications, as this excerpt illustrates,

[Participant with ABI] has been employed multiple times, but only for really short stints. Before the CoLab pathway she either didn’t make it through probation, or just made it through, and then cracks would start to show. I guess it showed that someone can manage for a period of time, but they do need supports around them to help when things aren’t going well. A big reason for the issues was that she didn’t want to disclose her ABI [Funder 5].

Some participants described how the challenges faced with finding employment had led to a lack of confidence finding employment. They said for example, ‘For [Participant with ABI], one of his biggest barriers was the confidence. He had been out of the workplace for so long that he really lacked that confidence in his abilities’ [Allied health professional / vocational provider 1].

Reflections on being employed

In the interviews which occurred 6–9 months after commencing employment, participants with ABI spoke positively about being employed, saying for example,

My whole life has changed. Before I was at mental breakdown, I was just clutching every moment of my life, I felt terrible. But now, I’m so happy, it’s changed my life. I love having a job, it is like my sense of identity is formed, because I’m doing well at a job. I’ve got responsibility and it’s made my life so wonderful and fabulous [Participant 4 with ABI].

All participant groups reflected on the increased confidence they had observed as a result of employment for the person with ABI. They said for example, ‘I have gained confidence in all areas of my life. I needed a chance, and now I have got one I’m trying to do well at it, and improve myself’ [Participant 3 with ABI]; and ‘[Participant with ABI] has certainly grown considerably in his confidence since coming into the role, with incidental conversations with staff in the tearoom through to having developed some skills around undertaking the requirements of the job’ [Employer 1].

However, participants with ABI and employers/co-workers identified fatigue as a factor impacting employment, and that part-time roles are a best-practice approach for people with ABI,

I used to work 60-90 hours a week, but now, I just can’t do long periods. I’ve been working three hours which is good, but when I did four hours the other day I was just fatigued. I currently work three days a week, and my goal is to work 15 hours a week [Participant 3 with ABI].

From the beginning, we were discussing starting part-time, and looking to gradually increase but she just wanted to be full-time. We looked to gradually increase her hours, but she just had so many external stresses, and issues with fatigue that it wasn’t possible for her to do full-time hours [Allied health professional / vocational provider 4].

Being supported

All participants spoke about the positive experience of Employment CoLab and spoke favourably about the various types of support received to find mainstream employment and then to maintain employment. This theme comprises four sub-themes: customised recruitment and human resource strategies, collaborative, flexible and team approach, needs of individuals with ABI last a lifetime, and value of tailored, rather than ‘cookie-cutter’ approach.

Customised recruitment and human resource strategies. Participants with ABI, allied health professionals/vocational providers and funders valued the customised approach of the pathway. This included the support to disclose their ABI, saying for example,

[CoLab Consultant] talked to my employer about my medical appointments, so I didn’t have to. That really helped, and my boss is lovely, and really supportive, well I mean, he hasn’t said no to me increasing my hours slowly, so that’s been good [Participant 3 with ABI].

Participants with ABI, employers and allied health professionals / vocational providers also spoke favourably about interviews being replaced with a ‘meet and greet’ model, which was conducted onsite so work tasks could be viewed and/or trialled. Comments included, ‘I liked being able to just have a bit of a walk around, and I could ask questions, and just chat and observe, that was so much better than an interview which I find too overwhelming’ [Participant 3 with ABI], and,

Having someone to call upon has been great, and for us, it was particularly helpful during the recruitment process, we have learnt a lot from [CoLab Consultant], and were happy to make the necessary changes to the way we recruit so that it is suitable for a person with ABI. [Employer 1].

Collaborative, flexible and team approach. All four participant groups discussed the importance of a collaborative, team approach as a key enabler to gaining mainstream employment of people with ABI, with close attention paid to both the employee, employer and co-worker needs,

My Physio has been great, as I needed to get stronger to do some elements of the job. The support of [CoLab Consultant] was great initially too, to advise and help me learn the specifics of the role. And also, my clinical psychologist, she’s been great, as I have been working through some sleep issues [Participant 2 with ABI].

I really like having the support of [CoLab Consultant]. I want to learn different ways of communicating with people, and being able to debrief with [CoLab Consultant] has been really helpful, and it’s been good to have access to some professional advice when needed [Employer 3].

Needs of individuals with ABI last a lifetime. Participants also recognised that the needs of individuals with ABI last a lifetime, and spoke about the importance of ongoing support that had been provided by Employment CoLab, and how they perceived this to have helped sustain employment, saying for example,

Yes, I’ve got the job, but my challenge is keeping the job. The support I have from [CoLab Consultant] is keeping me in line. I need that support, it is crucial, and would really like to continue with this support for the foreseeable future. Keeping the job is where [CoLab Consultant] is crucial to me [Participant 4 with ABI].

Typically, the role of voc providers is to find work, not necessarily to support someone to keep work, or that’s been my experience anyway. And I think one of the most important parts of Employment CoLab for [Participant with ABI] has been that ongoing follow-up, because it is not necessarily about just the finding work it’s having a job and keeping a job, and I have found that quite an essential part of what’s helped them [Allied health professional/vocational provider3].

Whilst allied health professionals / vocational providers and funders recognised the important of ongoing support, these two participant groups raised concerns about how this would be funded, as this excerpt illustrates,

I think it is vital, and a good component of the pathway, but it is a challenge I suppose about how that can be funded, as it becomes an issue. But sometimes, things can be stable for 3 years and the wheels come off again, so I do think it is important to keep track of things and be able to identify when something changes, and that we don’t miss something [Funder 4].

Nevertheless, funders also acknowledged that Employment CoLab had reduced their workload, which has the potential to offset some of the ongoing support costs. They said for example,

There are some clients where we might be having more contact with the employer, and on this occasion, it meant I had less, and it’s really been through feedback that we’ve received through [CoLab Consultant], as opposed to me initiating that with the employer. For me that was quite helpful, because it can be challenging for us to get too involved in the workplace, sometimes it’s better to have that other party who’s really, got the skills in an area. So, I felt quite comfortable with someone else doing that, and it has reduced my workload [Funder 4].

Value of tailored, rather than ‘cookie-cutter’ approach. Allied health professionals/vocational providers and funders spoke about the value of the pathway being a tailored, rather than ‘a cookie-cutter’ approach, and believed Employment CoLab could address some of the barriers to employing people with disability. They said for example,

[Participant with ABI] had previously been with a Voc provider who had really gone with that ‘cookie cutter’ approach of, you know, you have to apply for however many jobs by your next fortnightly appointment and all those sorts of things. There was such a combination of errors, and they were going with a really standard approach, and it was never bound for success, to be honest. You just can’t assume that everyone with a brain injury is going to need the same support. Everyone has their different things. I think this pathway is really flexible, and I think that’s why it’s potentially been a success for him, and could help other people too, just because of that personal approach, and that really targeted support, that is flexible to the person’s needs [Funder 4].

The pathway is pretty amazing. I think it could be that missing gap of getting more people with a disability into the workforce…You have the option of employment unsupported or supported employment which is the other extreme. So, Employment CoLab is almost middle ground [Allied health professional / vocational provider 1].

Explorative economic evaluation

Over 42 months, the total costs borne by the insurer were $163,503.84 (SD $122,088.98) per person utilising CoLab employee pathway compared to $201,193.45 (SD $222,069.28) per person utilising the traditional employment pathway. This resulted in an observed lesser cost for the CoLab employees by −$37,689.61 (95%CI −$274,004.18 to $198,624.97; p = 0.673). Isolating the vocational costs, over 42 months, the costs were $11,396.30 (SD $4322.10) per person utilising CoLab employee pathway compared to $7147.88 (SD $7585.92) per person utilising the traditional employment pathway. This resulted in an observed higher cost for the CoLab employees by $4248.42 (95%CI −$4173.13 to $12,669.97; p = 0.224). Finally, isolating the vocational costs to just the final 6 months, the costs were $3717.33 (SD $1621.36) per person utilising CoLab employee pathway compared to $1069.21 (SD $2588.81) per person utilising the traditional employment pathway. This resulted in an observed higher cost for the CoLab employees by $2648.12 (95%CI −$572.63 to $5868.88; p = 0.097). Average weekly hours of work for the final employment were 16.33 (SD 13.05) per person utilising CoLab employee pathway compared to 16.17 (SD 16.60) per person utilising the traditional employment pathway, with no between group difference (MD 0.17; 95%CI −26.75 to 27.09; p = 0.985). Due to high variability and a small sample size, this explorative economic evaluation was unable to detect significant differences to determine if the CoLab pathway was, or was not, less costly or more effective when compared to traditional employment pathways.

Discussion

In Australia, people with ABI experience low employment rates compared to the national average and others with disability (ABS, 2018; AIHW, 2019). The bespoke and customised employment pathway (Bould & Callaway, Reference Bould and Callaway2021) trialled in this study showed potential to improve employment outcomes for people with ABI. This research does however further highlight the need for focus on the person-activity-environment fit – flexible interventions were required to be developed with the person with ABI (e.g. skill building supports, cognitive compensatory strategies), as well as the employer and co-workers (e.g. ABI education and identification of well-defined work tasks) and the work environment (including environmental adaptations and identification of reasonable adjustments) (Australian Network on Disability, 2018; Gentry et al., Reference Gentry, Kriner, Sima, McDonough and Wehman2015; Weaver, Reference Weaver2015). However, these individualised responses required make research evaluation – including comparison of costs and outcomes – challenging.

Whilst this is the first Australian study to pilot an economic framework to evaluate vocational support for people with ABI, a conclusive position on whether the vocational model piloted – Employment CoLab – is more cost-effective than other vocational services a person with ABI may access could not be fully established. Of the limited evidence that exists on costs and outcomes of ABI vocational rehabilitation, the majority has been undertaken with participants early post-injury (Radford et al, Reference Radford, Sutton, Sach, Holmes, Watkins and Forshaw2018). Many of these studies have proposed future research using randomised controlled trials, which are often more feasible for implementation within rehabilitation settings where both the participant cohort and the intervention can be well controlled. This is in contrast to the varied and customised vocational supports and responses individuals who are longer post-injury and community-dwelling benefit from (Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, Wood, Phillips and Macey2013; Radford et al, Reference Radford, Sutton, Sach, Holmes, Watkins and Forshaw2018). In Australia, government investment in disability and injury insurance lifetime care schemes is significant. Employment following ABI is an identified area of outcome that requires sustained attention beyond the acute rehabilitation phase in order to mitigate scheme impacts and costs long term (Commonwealth of Australia, 2020; Department of Social Services, 2020). Flexible intervention models are therefore necessary.

The Employment CoLab pathway, and associated pilot, was implemented with people who had completed their inpatient rehabilitation and returned to community living, and this is in contrast to other clinical trials published to date (Ntsiea et al., Reference Ntsiea, Van Aswegen, Lord and Olorunju2014; Radford et al., Reference Radford, Sutton, Sach, Holmes, Watkins and Forshaw2018). The pilot purposely aimed not to exclude those who were longer post-injury or experienced dual diagnosis (e.g. ABI plus a mental health diagnosis or physical health condition). As such, the participants were heterogeneous in nature, were a minimum of 4 years post-injury, and experienced a range of complex mental and/or physical health conditions in addition to their brain injury. This led to a participant group with complex and multiple needs, and limited recent pre-employment or employment experience, seeking employment transition. This factor may in part have impacted employment outcomes for some participants; however, employment needs and goals of this group must also be addressed. Pleasingly the Employment CoLab pilot led to all participants obtaining work, and did not see any employment role cease as a result of this complexity.

A key finding from the qualitative evaluation was that the collaborative and sustained nature of both employer engagement to identify work opportunities (and thus circumvent the need for formal job applications and interviews for people with ABI), in addition to the vocational support offered through the Employment CoLab model, grew both employee and employer confidence. This approach also allowed rapid identification of the need for additional input from the CoLab consultant to sustain employment, and is aligned with long standing guidance in the field of ABI regarding the need for place-and-train approaches to employment, and models of lifetime care (Willer & Corrigan, Reference Willer and Corrigan1994). Although due to the small number of participants it cannot be assured, this finding may point to the benefits of this pathway for those with multiple and complex needs, and also the importance of episodic input over time (Bond, Reference Bond2004; Hart et al., Reference Hart, Dijkers, Whyte, Braden, Trott and Fraser2010). If employment outcomes are to be positively influenced as part of effective neurological rehabilitation, the intensity of these episodic and customised supports required must be considered (Sutton et al., Reference Sutton, Ottomanelli, Njoh, Barnett and Goetz2020).

Previous research has highlighted there is significant start up expenditure associated with employment programmes, with higher costs incurring in the initial stages of input (Radford et al., Reference Radford, Sutton, Sach, Holmes, Watkins and Forshaw2018). Ongoing attempts to deliver a range of innovative approaches to open employment are to be encouraged, but will likely require supply-side investment to meet demand (NDIS, 2019). The Employment CoLab model, or key features of the pathway, could be built into vocational services provided to people with ABI, with a particular focus on early employer engagement, workplace adaptations and job carving. These align with the contemporary evidence on characteristics of work and workplaces that retain their employees following ABI. Specifically, ‘efforts should be taken by employers to understand which types of work adaptations or other intervention efforts employees need to be able to retain work … possible modifiable efforts might be tailoring work tasks, supplying workplace support and adapting work hours’ (Alves et al, Reference Alves, Nilsen, Fure, Howe, Løvstad and Fink2020, p. 128).

Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic has added another layer of challenge to people with ABI finding and maintaining employment. Fortuitously, the employment roles secured via Employment CoLab were in industries that were less affected by COVID. These included accommodation and food services, traffic management, and administrative and support services. This is an important and unexpected learning regarding the types of industries less impacted by a pandemic, that may be considered as the ongoing uncertainty of the COVID environment, and its impact on employment, continues.

Study limitations and recommendations

There were a number of limitations in this study. Difficulties with building employer collaborations limited the number of identified roles that were able to be filled by a person with ABI. Consequently, the findings are based on a small sample size across four stakeholders and only a subset of these participants consented to participation in the individual interviews and explorative economic evaluation. Further, the wide 95% confidence intervals noted for the explorative economic evaluation most likely represent a sample size that was too small, and data too varied, to detect change, indicating that the results need to be interpreted with caution. It would be valuable to further explore this methodology and its utility to understand economic impact of new service models. However, future research will require study designs that can accommodate the individualised intervention design required (e.g. single-case experimental design, in contrast to controlled trials), whilst ensuring larger samples sizes to be able to detect change or significant differences.

This study also only collected data up to 9 months post-employment. Previous research has identified the ability for people with ABI to gain, but regularly not sustain, open employment due to the often-complex nature of cognitive behavioural issues that exist (Dahm & Ponsford, Reference Dahm and Ponsford2015; Donker-Cools et al., Reference Donker-Cools, Daams, Wind and Frings-Dresen2016; Howe et al., Reference Howe, Andelic, Perrin, Røe, Sigurdardottir and Arango-Lasprilla2018; Libeson et al., Reference Libeson, Downing, Ross and Ponsford2020). The return to work plan included in the Employment CoLab pathway was found to be important in ensuring both the employee and employer could manage the collaborative employment approach; however, it does not dispel the complex needs a person may experience after brain injury. These may continue to impact on valued life roles – including employment – over time, thus requiring episodic input over the lifetime of the role. To ascertain whether the provision of ongoing support included as part of Employment CoLab can address the issue of employment breakdown for people with ABI, a longitudinal study would therefore be required. A longitudinal study could also monitor and evaluate the cost and the effectiveness of the ongoing support provided to the employee and employer, which could be via personnel of varied type and frequency. For example, it could include review input by the funding body or their appointed internal employment or claims team, or through episodic funded vocational provider support, such as that provided by the CoLab Consultant or via an annual insurer Functional Independence Review process.

Conclusion

Employment CoLab was found to offer an effective team approach for seven people with ABI to gain and sustain open employment and wages, through a collaborative model between the employer, employee with ABI, vocational support stakeholders and disability or injury insurance funders. Whist a potential scalable approach to ongoing implementation of Employment CoLab has been established, it would be valuable to continue to build the evidence base of open employment outcomes achieved, and those sustained, by a larger number of people with ABI and their employers using Employment CoLab versus other traditional vocational pathways.

Financial support

This study was funded by the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources, through the Jobs Victoria Innovation Fund, project number GA-F75357-2388, as well as funding from the Transport Accident Commission.

Conflicts of interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.