To the Editor—Klebsiella pneumoniae is the second most frequently isolated organism from blood cultures after Escherichia coli in India, with 50% of all K. pneumoniae isolates being resistant to meropenem in 2019. 1 Infections due to carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) are difficult to treat and have serious implications for patient health and medical costs. Reference Huang, Qiao and Zhang2 Two recent meta-analyses Reference Liu, Li and Luo3,Reference Zhu, Yuan and Zhou4 reported the risk factors of CRKP infections; however, none of the studies included in the meta-analyses were from India or South Asia, where CRKP infections are highly prevalent. Reference Gandra, Alvarez-Uria, Turner, Joshi, Limmathurotsakul and van Doorn5 The high burden of CRKP in Indian healthcare settings necessitates investigation into the risk factors for CRKP infections to identify potential interventions. Here, we examined the risk factors associated with CRKP bloodstream infections (BSIs) compared to carbapenem-sensitive K. pneumoniae (CSKP) BSIs in the Indian context.

A retrospective study was conducted at Medanta–The Medicity, a tertiary-care hospital with 1,500 beds in North India between August 2014 and July 2015. Patients with BSI caused by K. pneumoniae were included in the study. Only the first BSI with K. pneumoniae from a patient was included. Data were collected by reviewing medical records. The variables included demographics, admission diagnosis, ICU admission, comorbidities, exposure to invasive devices, immune status, prior exposure to antibiotics, length of hospital stay and outcome. The blood-culture specimens were processed using BacT/Alert 3D (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) blood-culture system. Identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed using a Vitek 2 compact instrument (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI 2015) break points were utilized. 6 Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables were reported as medians and interquartile ranges. For univariate analyses, results were reported as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals and P values. Variables with P values <.10 in the univariate analyses were included in backward, stepwise, logistic regression to determine the final multivariate logistic regression model to evaluate risk factors for CRKP. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 26 software (IBM, Armonk, NY). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Medanta Hospital, and the requirement for obtaining informed consent was waived because of the study’s retrospective design.

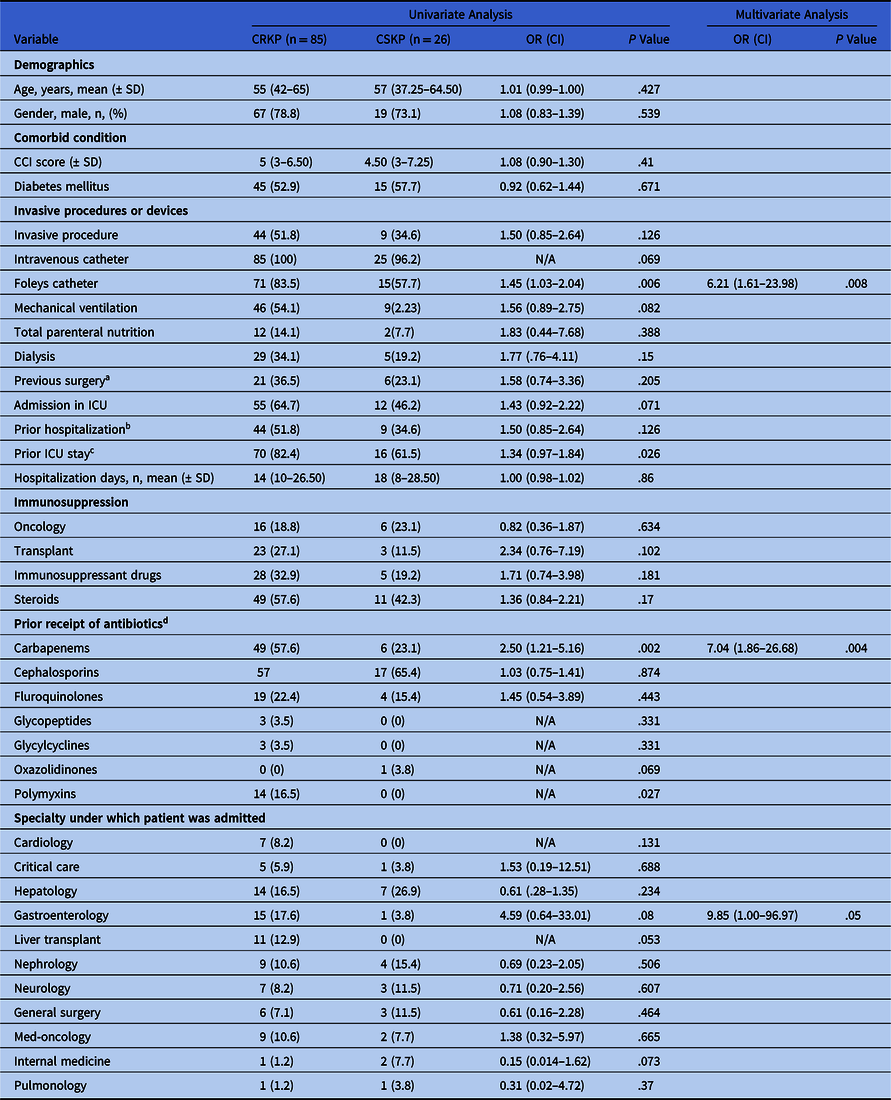

Overall, during the study period, 111 patients had K. pneumoniae BSI. Of 111, 85 patients (77%) had CRKP and 26 patients (23%) had CSKP BSI. In univariate analysis, the following variables were associated with CRKP BSI: prior use of carbapenems, prior ICU stay, presence of foley catheter, mechanical ventilation, admission to ICU, prior use of polymyxins, admission to gastroenterology service and admission to liver transplant service (Table 1). However, in multivariate analysis, prior carbapenem use (odds ratio [OR], 7.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.86–26.68; P = .004), presence of Foley catheter (OR-6.21; 95% CI- 1.61-23.98; P = .008) and admission to gastroenterology service (OR, 9.85; 95% CI, 1.00–96.97; P = .05) were associated with CRKP BSI (Table 1). The in-hospital mortality rates were 42.4% (36 of 85) and 23.1% (6 of 26) among CRKP and CSKP patients, respectively. In univariate analysis the in-hospital mortality was higher in CRKP patients (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.99–1.47; P = .07); however, it was not statistically significant in multivariate analysis.

Table 1. Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Risk Factors Associated With Carbapenem-Resistant K. pneumoniae Bloodstream Infection (CRKP BSI)

Note. CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; CSKP, carbapenem-susceptible KP; ICU, intensive care unit; KP, Klebsiella pneumoniae; SD, standard deviation.

a Surgery within 30 days prior to collection of blood culture.

b Hospitalization within 3 months prior to collection of blood culture.

c ICU admission within 30 days prior to collection of blood culture.

d The exposure had occurred during the current hospitalization before the blood culture was obtained or previous hospitalization within 30 days and a systemic antibiotic was administered for at least 1 day.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report on the risk factors associated with CRKP infections in India. Our findings are consistent with the 2 recent meta-analyses that reported carbapenem exposure and the presence of Foley catheter as risk factors for CRKP infections. Two other factors, namely mechanical ventilation and admission to ICU, which were identified as risk factors in meta-analyses, were significant in univariate analyses but not in multivariate analysis. This could be due to our small sample size. A recent prospective study conducted in several low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) reported increased in-hospital mortality with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) BSIs. Reference Stewardson, Marimuthu and Sengupta7 We observed higher mortality in univariate analysis but not in multivariate analysis, which could also be related to the small sample size of our study.

We observed that patients admitted to gastroenterology service had higher odds of CRKP BSI. The gastrointestinal tract is a site for K. pneumoniae colonization, Reference Paczosa and Mecsas8 and patients admitted to gastroenterology units are inflicted with erosive or inflammatory pathology; mucosal damage can predispose them to translocation of gut flora into the bloodstream. Contaminated endoscopes have been causally linked to multidrug-resistant organism outbreaks in the past Reference O’Horo, Farrell, Sohail and Safdar9 ; however, we did not capture the number of endoscopic procedures among CRKP and CSKP patients. Moreover, the increased use of carbapenems in this patient subset can further contribute to the high rate of CRKP infections. However, the 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio is wide, reflecting that the need for a bigger sample size to confirm this association.

The high burden of CRKP BSI in Indian hospitals is of concern because there are no effective antibiotic treatment options. None of the recently approved antibiotics Reference Sheu, Chang, Lin, Chen and Hsueh10 are active against the New-Delhi metallo-β-lactamase–producing strains of CRE, which are highly prevalent in India. 1 Our findings reinforce the need for appropriate use of carbapenems and infection control practices in Indian hospitals. There is an urgent need for effective interventions aimed at improving antimicrobial stewardship and infection preventions programs in Indian healthcare settings to effectively manage CRKP BSIs.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.