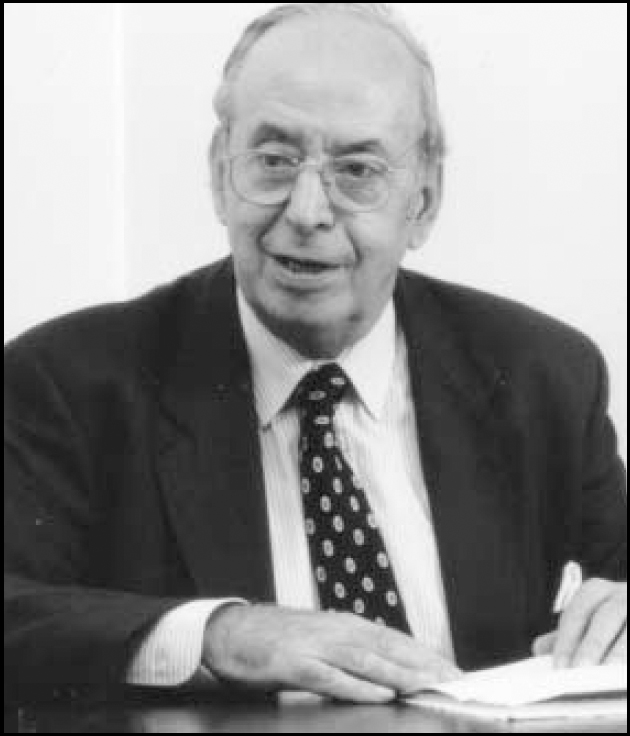

Silvio Benaim died on 10 January 2008 at Highgate Nursing Home, London, after a long illness. He was a senior consultant psychiatrist at the Royal Free Hospital since 1968, having been a consultant at Halliwick Hospital from 1959. He retired from the National Health Service (NHS) in 1983 but continued his private practice at the Charter Nightingale Clinic until 2004.

Silvio was born in Florence on 11 April 1925. His father was a Jewish lawyer. In 1938, Fascist Italy introduced racial laws which discriminated against him and his family, so that they moved to England. Silvio was educated at Leighton Park School, Reading. He qualified in medicine at Westminster Medical School MB, BS (London) and MRCS, LRCP in 1948, and then pursued broad general medical training, including neurology and chest medicine, leading to the MRCP (London) in 1952, and being elected FRCP in 1971. He trained in psychiatry at the Maudsley Hospital, enrolling in the model rotation programme for which it became famed. Over the course of nearly 6 years he progressed through the grades of senior house officer, registrar and senior registrar, at the same time obtaining the academic DPM in 1956 with a dissertation on obsessional symptoms in the elderly, and was elected FRCPsych in 1971. He assisted in the treatment trial of insulin coma therapy which sounded the death knell of that approach in schizophrenia.

From the time of his arrival in England, aged 13, Silvio quickly became acclimatised and spoke English without any trace of an accent. At Silvio's funeral his second son, Michael, paid a moving tribute and quoted his uncle's appraisal of Silvio's loyalties through a mathematical paradox: he was 100% British and yet 50% Italian. Thus, he maintained a deep loyalty for the country of his birth where he kept a holiday home near Siena. He was greatly interested in Italian psychiatry and in 1983 wrote an article with the title ‘The Italian Experiment’. Previously, in the early 1960s, he had visited university departments of psychiatry across Italy and remarked on the variable standards of psychiatric care, good in many centres, deplorable in others. He described the sequels of the ‘Law 180’ or ‘Basaglia's Law’, passed hurriedly in 1978, as without due regard to the human and scientific principles which should guide psychiatric care. In Britain there was unalloyed condemnation of the consequences of this new Italian law which barred further admissions to the old hospitals. Instead, patients were to be admitted to general beds in district general hospitals, none of which were to accommodate more than 15 psychiatric patients at one time. For a while the standard of care in mental hospitals deteriorated and many patients slept rough. Nevertheless, Silvio was generally sympathetic to the need for reforming the Italian mental hospitals and put forward several proposals for further reforms, some of which came to pass.

The main problem with the new law was the difficulty in discharging patients who required intensive psychiatric rehabilitation without the availability of day hospitals, day centres and community services. The 1978 law is still in force, but therapeutic communities are now in place. In Italy there persists an unrealistic dread of opening additional psychiatric beds, for example, in specialities within psychiatry.

Silvio's research was initially in the evaluation of the early antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs, including a controlled trial of imipramine. As a consultant he achieved a steady output of clinico-scientific articles, impressive for their originality and for their impact on the profession. The most vivid was his detailed description of an hysterical epidemic in a classroom affecting 24 adolescent girls. It began when 8 pupils and 1 young teacher lay unconscious on the floor. He included clinical vignettes such as the patient who, when admitted to a psychiatric ward, started a pseudo-pregnancy epidemic in that ward. As a consultant at the Royal Free Hospital, Silvio had undoubtedly become sensitised by the controversies of the Royal Free disease of 1958, initially diagnosed as benign encephalomyelitis, but later reconsidered by McEvedy and Beard to be an hysterical epidemic among the nursing staff.

In another influential article published in 1987, Silvio described the long-term benefits of prophylactic lithium carbonate in 100 patients with unipolar or bipolar affective illness, whom he had assessed personally. Several previous controlled studies had established the efficacy of prophylactic lithium in such patients. Silvio's study was the first to follow-up these patients over a period of 17 years, the majority of whom were traced. The eventual outcome findings were impressive: 50% had a complete and 40% a partial response. Lithium was equally effective in preventing hypomanic and depressive episodes.

As a psychiatrist, Silvio had been much influenced by the ethos of the Maudsley Hospital in the late 1950s. When Henry Maudsley made his donation to the London County Council in 1908 to establish a psychiatric teaching hospital in London, he proposed that it would be devoted exclusively to the care of early and acute cases, so as to prevent deterioration and admission to the county asylums. Silvio was frank in asserting that his own clinical interests were in treatable psychiatric conditions, while still practising broadly-based psychiatry including neurotic disorders. He wanted to help patients who had a chance of getting better. Thus, he became uneasy when in the mid 1960s, as part of his post, he felt obliged to combine his work at Halliwick with that of the adjoining Friern Hospital. This changed when he was appointed to the Royal Free Hospital and worked alongside physician colleagues. All too often, at that time, senior psychiatrists withdrew from direct contact with their patients by delegating the work to other members of their team or indulging in committee work. This was not Silvio's style. He had a tremendous zest for clinical work. His approach was attractive to general practitioners. He soon built up a thriving private practice, but he never neglected his NHS work. After retiring from the NHS, he continued his private practice until 2004 when illness forced him to give up this work.

Silvio was admired and liked by his colleagues for his avuncular manner, his unfailing courtesy and his loyalty. His preferred method of teaching psychiatry was in the out-patient clinic where he acted as a close mentor to generations of senior registrars.

Sadly, Silvio developed a prolonged and disabling neurological illness, but for this he obtained comfort and support from the sustained devotion of his wife Nancy, his three sons and his four granddaughters.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.