1 Introduction

The grammaticalization of the English modals has been the object of numerous studies and the source of much controversy. However, certain aspects of the history of the modals have attracted less attention. This article focuses on one such aspect, namely the apparent development of weak-verb morphology in a number of modals in Middle English. Specifically, in some of the modals the expected present indicative plural suffix -en was substituted by -eþ (-eð, -eth, etc.), though not in all dialects and not to the same extent in every modal. Forms with -eþ are often found alongside the older variant with -en, even within the same manuscript. Compare the historically expected form scullen in (1) with the innovative form sculleð in (2). Both of these examples are from Laȝamon's Brut (Cotton Caligula A ix; c.1200).Footnote 2

(1) ⁊ ȝe scullen of me halden ; And habben me for harre

‘And you have to be faithful to me and acknowledge me as your lord’ (Lay.Brut (Clg A.9); LAEME, layamonAbt, f32rb)

(2) Gabius and Prosenna . þe sculleð eow wurðliche wreken

‘… Gabius and Prosenna, who are going to avenge you honourably’ (Lay.Brut (Clg A.9); LAEME, layamonAbt, f34rb)

Forms like sculleð in (2), which I will refer to as ‘regularized’ plurals, are mentioned in passing by a few authors (see section 2), but do not appear to have been investigated in any detail. They are of importance for a number of reasons, however, both for the history of the modals and for Middle English dialectology. As I note in section 2 below, many authors writing on the modals have taken their special inflectional morphology to be an important factor in their historical development, but forms like sculleð in (2) might seem to indicate that the modals in Middle English in some ways behaved like regular weak verbs and were not (yet) treated as a special class. On a more general level, the question arises why inflectional changes like this one happened to some items, but not others, and only in certain Middle English dialects.

In the following, I will investigate the development and distribution of regularized plural modals in early and later Middle English texts. In doing so, I will attempt to answer the following two research questions:

1. Where and when are regularized plural modals attested in Middle English?

2. Is it possible to explain the distribution of these forms?

Because some of the forms under investigation are only very sporadically attested, it is necessary to search as many sources as possible to get a comprehensive picture of their distribution. In addition to two electronic atlases of Middle English dialects, I have used a number of large corpora, which will be introduced in section 3. Section 4 then presents the findings on the three modals which are found with regularized plurals, namely shall, can and may. This is followed by a discussion of the dialectal distribution of the forms in section 5, where I also attempt to account for the observed patterns and discuss their implications for the history of the modals. Section 6 offers some concluding remarks.

2 Earlier work

The literature on the English modal verbs is abundant, and this section will only discuss the works most directly relevant to their morphology in Middle English. For useful overviews of the history of the modals and earlier literature on the subject, one may consult e.g. Denison (Reference Denison1993: 292–339) or Fischer (Reference Fischer2007: 159–209).

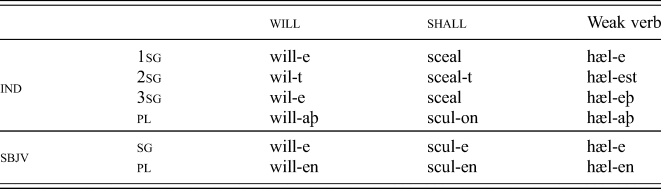

As is well known, the modals historically belong to the small inflectional class usually known as preterite-presents. In Old English, this class had twelve members, including the ancestors of most of the Present-Day English modals as well as verbs like unnan ‘grant’, witan ‘know’ and gemunan ‘remember’. The verb will did not belong to this class and is traditionally treated as a morphologically ‘anomalous’ verb in Old English grammars (e.g. Campbell Reference Campbell1959: 346). The present-tense paradigm of will is shown in table 1 along with a (somewhat simplified) paradigm of the preterite-present verb shall and a regular weak verb, hælan ‘heal’; for further information on the morphology of will and the preterite-presents in Old English, see e.g. Campbell (Reference Campbell1959: 343–7) or Hogg & Fulk (Reference Hogg and Fulk2011: 299–308, 320–2).

Table 1. Old English (West Saxon) prs paradigms

The Middle English period saw many changes to the verbal morphology of the language. Some were due to phonological changes, such as the merger of most unstressed vowels into /ə/, which resulted in -eþ from earlier -eþ and -aþ, and -en from earlier -en and -on (Lass Reference Lass and Blake1992: 77–8, 134–7). Final -en was often further reduced to -e (see Minkova & Lefkowitz Reference Minkova and Lefkowitz2019). Other changes were analogical in nature, such as the generalization of -e(n) as the prs.ind.pl marker in all verb classes in some dialects, mainly in the east and northwest Midlands. In other dialects, the original prs.ind.pl suffix survived as -eþ, and as examples like (2) show it was even extended to some of the modals, which in Old English had the suffix -on. It is this development which will come under scrutiny in the following.

The earliest discussion of the development which I have found is Bryan (Reference Bryan1921). Bryan's main goal is not to explain the regularization of the modals, but rather to account for the spread of -e(n) as the general prs.ind.pl suffix in the east and northwest Midlands. He identifies three possible sources for this suffix: the subjunctive, the past tense and the preterite-presents. In the first two cases, -e(n) would have spread to the prs.ind.pl through intraparadigmatic analogy. In the last case, the analogical extension would be interparadigmatic, -e(n) ‘jumping’ from the preterite-presents to the larger classes of weak and strong verbs. According to Bryan, the last scenario is the most likely one. He argues that there was a close relationship between the different inflectional classes, ‘so close that personal endings belonging properly to one class … were transferred to the other’ (Bryan Reference Bryan1921: 133–4). The fact that the ‘normal’ (i.e. weak) prs.ind.pl suffix -eþ was sometimes used with preterite-present verbs is mentioned as evidence for this close relationship. The reason for the development of forms like sculleð in (2) was thus, according to Bryan, analogical influence from weak and strong verbs.

A conclusion similar to Bryan's is reached by Warner (Reference Warner1993), who considers the ‘reformed’, i.e. regularized, present indicative plural forms as part of a more general discussion of the status of the modals in Middle English. Warner bases his survey on McIntosh et al. (Reference McIntosh, Samuels and Benskin1986) and the historical dictionaries and finds examples of regularized plural forms of shall, can and may, the last of these ‘apparently less frequently’ than the other two (Warner Reference Warner1993: 101). In addition to these verbs, regularized plural forms are attested in a few other (non-modal) preterite-presents, namely witen ‘know’ and unnen ‘grant’, as well as in ouen which eventually ‘splits’ into owe and ought (OED, qq.v.). (I return to the ‘non-modal’ preterite-present verbs below.) According to Warner, the fact that some modals developed regular plural suffixes suggests that they were still felt to be part of the larger category of verbs. Unlike Bryan, Warner considers the possible role of the prs.ind.pl form of will as a model for the analogy, at least in the case of shall. He notes, however, that regularized plural forms of will and shall do not always co-occur in the manuscripts surveyed by McIntosh et al. (Reference McIntosh, Samuels and Benskin1986): ‘the presence of shulleþ as a normal form in a manuscript by no means implies the presence of willeþ’ (Warner Reference Warner1993: 101). In other words, while will must have influenced the development of shall, according to Warner it cannot have been the only source of the spread of regularized morphology.

The development of innovative plural forms has since been referred to by a few other authors in discussions of the modals. Fischer (Reference Fischer2007: 171) and Trousdale (Reference Trousdale, Brinton and Bergs2017: 108) both refer to Warner's analysis and cite forms like sculleþ and cunneþ as evidence that the modals in some ways became more ‘verb-like’ in Middle English. The change does not appear to have been investigated in its own right, however, and the major Middle English handbooks and textbooks only mention the phenomenon in passing, if at all (see e.g. Burrow & Turville-Petre Reference Burrow and Turville-Petre2005, s.v. con, can). There is of course no fault in this, for the development in question is only a short chapter in the much longer story of the modals, and one which has left no traces in the modern language. However, if one considers the prominence attached to morphology in the literature on the modals, it may well seem somewhat surprising. Beginning at least with Lightfoot (Reference Lightfoot1979: 100–3), most scholars working on the modals have agreed that their special morphological properties must have played some role in their grammaticalization into auxiliaries, even if opinions differ as to how important the morphology was (see e.g. Plank Reference Plank1984: 311–12; Warner Reference Warner1993: 140–4, 204–6; Nagle & Sanders Reference Nagle, Sanders, Fisiak and Krygier1998; Fischer Reference Fischer2007: 163). For instance, Nagle & Sanders (Reference Nagle, Sanders, Fisiak and Krygier1998: 258) consider it ‘plausible, if not highly probable’ that modal semantics and preterite-present morphology gradually became so closely associated that it led to the formation of a separate syntactic class of modal auxiliaries.

At first glance, the development of modal plurals like shulleþ would seem to suggest that there was no strong connection between modal meaning and preterite-present morphology in Middle English. If prs.ind.pl -eþ spread to the modals from regular verbs, this suggests that the modals were still felt to be part of the larger category ‘verb’ in Early Middle English, as Warner (Reference Warner1993) indeed concludes. In the literature on grammaticalization, it is generally assumed that grammaticalizing items become more, not less, irregular (see e.g. Lehmann Reference Lehmann2015: 145–6), so under this interpretation the spread of -eþ might be taken as evidence that the modals were not yet grammaticalizing in Middle English. If, on the other hand, the spread of -eþ proceeded not from the regular verbs, but from the ‘anomalous’ verb will, the opposite conclusion might be reached: will and the other modals were already felt to form a separate class in Middle English, and developed increasingly similar morphology as a result. The significance of the innovative prs.ind.pl suffix for the history of the modals thus depends on the origin of the innovation.

One could in principle investigate the whole class of preterite-presents together, but for a number of reasons I have limited this investigation to three ‘core’ modals, shall, can and may. The modal mot (must) does not seem to be attested with prs.ind.pl -eþ at any stage. Other (non-modal) preterite-presents developed regularized morphology as well, but some of these are either very infrequent in Middle English (e.g. unnen ‘grant’) or present special challenges of their own. The verb ouen (← OE agan), for instance, follows a rather different trajectory from the other preterite-presents by splitting into the weak verb owe and the defective modal verb ought, originally a past-tense form (see Ono Reference Ono1960). The history of the non-modal witen is no less complicated and would in fact seem to deserve an entire study of its own.Footnote 3 Finally, the preterite-present (and ‘marginal’ modal) dare (MED, s.v. durren) also develops regularized morphology, but this only happens in Early Modern English (see OED, s.v. dare v.1) and concerns the whole paradigm, not just the prs.ind.pl. By contrast, the regularization of the three ‘core’ modals shall, can and may happens several centuries earlier and only seems to affect the prs.ind.pl.Footnote 4

In the following section, I present the material used to investigate the spread of prs.ind.pl -eþ in shall, can and may.

3 Material and search methods

The increased availability of historical corpora has made it easier to investigate language change across several centuries, but also to study more ‘local’ (and often less prominent) linguistic developments. The innovative plural modals are a case in point. As mentioned in the previous section, Warner (Reference Warner1993) used McIntosh et al. (Reference McIntosh, Samuels and Benskin1986) to survey the occurrence of regularized plurals in Late Middle English, but since then a number of additional resources have become available, most importantly A Linguistic Atlas of Early Middle English, 1150–1325 (LAEME; Laing Reference Laing2013) and An Electronic Version of A Linguistic Atlas of Late Mediaeval English (eLALME; McIntosh et al. Reference McIntosh, Samuels, Benskin, Laing, Williamson and Karaiskos2013), an online version of McIntosh et al. (Reference McIntosh, Samuels and Benskin1986). These two linguistic atlases differ in a number of ways. The eLALME is based on questionnaires that survey the linguistic features of Late Middle English scribal texts. For each text a ‘Linguistic Profile’ (LP) was created with information about the forms of a number of frequent linguistic items. Based on these LPs, the texts were fitted to geographical anchor points; one can map the distributions of forms found in the LPs with the online version. The LAEME, by contrast, is corpus- rather than questionnaire-based. Instead of a LP, a close transcription was made of each scribal text, either in its entirety or of an excerpt. This makes it easier to survey variation within texts and, of course, makes it possible to use the atlas as an Early Middle English corpus.Footnote 5

In the LAEME, I surveyed the lists of attested forms (‘Item Lists’) of the lexemes (‘lexels’) in question and identified potentially relevant ones. For instance, by creating an Item List for the lexel shall with a grammatical tag (‘grammel’) beginning with ‘vps2’, one retrieves all prs.ind.pl forms in the corpus: schulen, shule, ssolleþ and so on. The relevant forms of shall and can could then be located in the individual texts. Regularized may was not found in this corpus.

In the eLALME, I surveyed the potentially relevant pre-defined dot maps and Item Lists, namely shall pl (item no. 22-30), can pl (no. 105-22) and may pl (no. 199-20). A map showing the distribution of regularized shall is already available in the atlas (see figure 2), but unfortunately the items can and may are only surveyed in the questionnaires from the northern half of England, where no relevant forms were found. For this reason I decided to search a number of other electronic corpora in order to identify as many examples as possible from the period, namely the Middle English Grammar Corpus (MEG-C; Stenroos et al. Reference Stenroos, Mäkinen, Horobin and Smith2011), the Innsbruck Corpus of Middle English Prose (ICMEP; Markus Reference Markus2010) and the Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse (CMEPV 2006). The MEG-C is similar to the LAEME corpus in that it is based on manuscripts rather than editions, but covers a later period (c. 1300–1500). The texts currently included in the corpus are all localized in the eLALME, making it well suited for investigations of dialectal variation. The main disadvantage is that the corpus is quite small (c. 664,000 words); see the corpus manual by Stenroos & Mäkinen (Reference Stenroos and Mäkinen2011) for further details. The two other corpora are much larger, but less well suited for variationist investigations. The ICMEP contains c. 9 million words, but is based on editions, and it is not always indicated which manuscripts the texts come from, e.g. in the case of composite editions based on more than one manuscript. The CMEPV repository does not come with a word count, but contains digital versions of some 300 text editions. Not all of these are equally reliable, and as with the ICMEP, it often requires some work to find out which manuscripts the editions are based on. It is also important to note that whereas the LAEME, eLALME and MEG-C take the scribal text as their basic sampling unit, the texts in the two other corpora do not usually contain information about changing scribal hands. The information about provenance for these texts should thus only be taken as approximate, and as noted in sections 4.2 and 4.3, not all of the texts could be securely localized. However, as I hope these sections will demonstrate, one can still investigate dialectal variation with these resources if the necessary precautions are taken.

The MEG-C, ICMEP and CMEPV are all plain-text corpora, i.e. there is no morphosyntactic tagging or lemmatization of the texts. For this reason, they had to be searched manually for possible spellings of the regularized plurals conneþ and moweþ, which were then exported to a spreadsheet.Footnote 6 All irrelevant examples (e.g. of the verbs mow and move) were then removed, along with ‘doublets’ from texts included in more than one of the corpora. A number of problematic cases will be discussed at the relevant points in the sections on can and may.

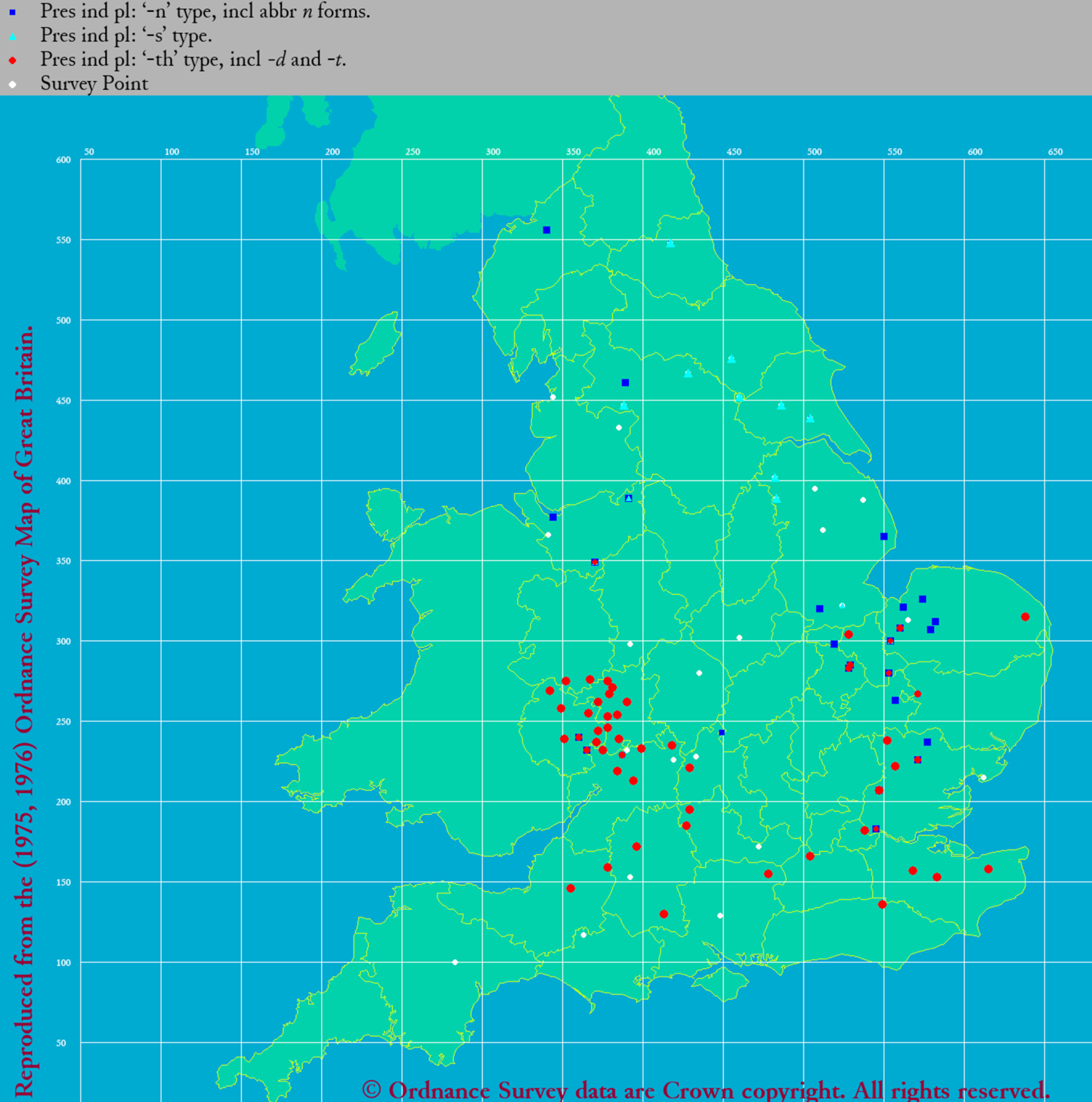

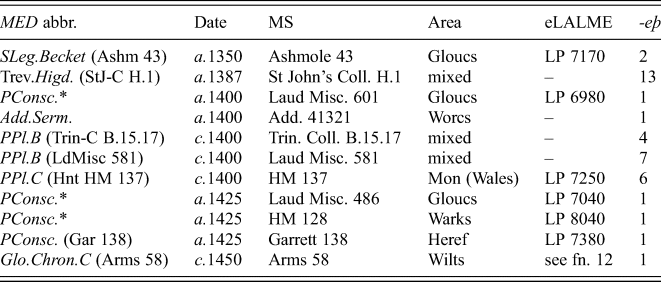

4 Findings on regularized plural modals

In the following the findings from the linguistic atlases and corpora are presented. I present the findings on shall first, followed by can and may. For each of the three modals, I include a table with an overview of the attestations in the LAEME sources or other texts, as appropriate. The main questions addressed in this section are where and when prs.ind.pl -eþ is attested in the modals. A very preliminary answer to the question of geographical distribution already emerges from figure 1, a LAEME dot map showing the general distribution of three types of prs.ind.pl suffixes in Early Middle English, i.e. in strong and weak verbs.Footnote 7 The dots represent the suffix -eþ (with spelling variants), the squares the suffix -en, and the triangles the Northern suffix -s. Overlapping symbols indicate that more than one variant is attested. As the map shows, the prs.ind.pl suffix -eþ is mainly found in the South and the southwest Midlands, which is consequently the general area where we expect to find this suffix extended to the modals. However, as the findings presented here will show, regularized modals were not evenly distributed across this general area.

Figure 1. prs.ind.pl suffixes, strong and weak verbs (LAEME)

4.1 Shall

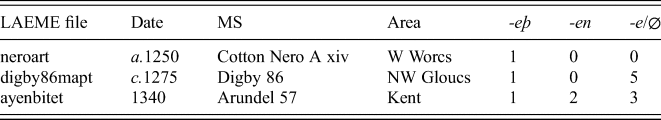

The Early Middle English material in LAEME contains regularized plural forms of shall and can, but shall is attested more frequently than can. As table 2 shows, regularized shall is recorded in five scribal texts in the corpus, all of them from the southwest Midlands. Table 2 gives the LAEME filenames, text information and the number of attestations of the prs.ind.pl suffixes found in the texts: regularized -eþ, historically expected -en and reduced -e/zero.Footnote 8

Table 2 attests to the variation found not just between scribal texts, but within them as well: in all five texts, -eþ is found alongside other variants. In one text, corp145selt (South English Legendary; Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 145), -eþ is the dominant suffix. An excerpt from this text with two examples of regularized shall is given in (3):

(3) Ȝe ssolleþ after seue monþes ⋅ yse[o] a uair ile Þat abbey is ycluped ⋅ þat is hanne mani a myle

Ȝe ssolleþ be[o] mid holy men ⋅ þis midwinter þere

‘After seven months you are going to see a beautiful island called Abbey, which is many miles away from here; you are going to spend Christmas there with holy men.’ (SLeg.Brendan (Corp-C 145); LAEME, corp145selt, f70v)

Table 2. Regularized shall in LAEME

In another text, layamonAbt (Laȝamon's Brut; Cotton Caligula A ix), a reviser of the manuscript has changed the original form swulleð to sullen:

(4) Mid strengðe we swulle[ð] wenden ; þurh ure wiþer-iwinnen

‘With force we are going to make our way through our enemies’ (Lay.Brut (Clg A.9); LAEME, layamonAbt, f25vb)

The editor comments on the form swulleð: ‘So original with final ð or d. Altered to sullen by revising hand’ (transcription adapted). We can thus safely say that at least one Early Middle English language user was aware of the variation between regularized and ‘etymological’ shall (and evidently preferred the latter).

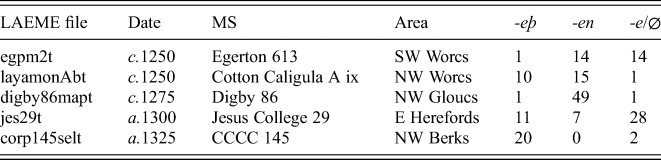

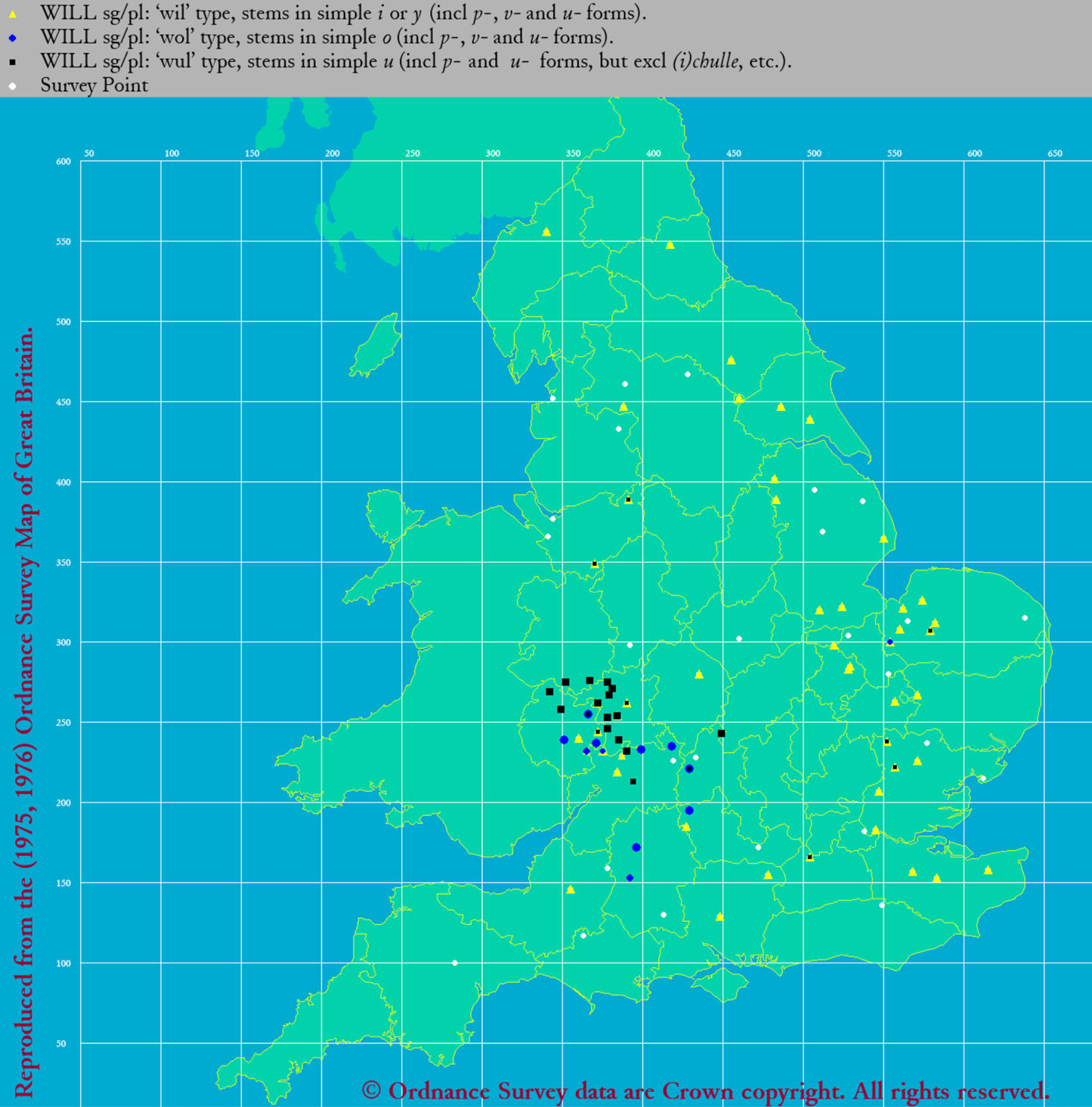

The Late Middle English material in the eLALME presents a different picture. At this point regularized plurals of shall appear to have spread to a larger area, also including southern East Anglia and most of the southern counties, as illustrated on the dot map in figure 2. This does not necessarily mean that the form was used in the spoken language in all locations on the map, only that it is recorded in documents from these places; these texts may in turn have been copied from exemplars originating elsewhere. Similarly to the Early Middle English situation, many of the manuscripts surveyed in the eLALME attest to competition between the suffixes. The example in (5) is from a manuscript (Cambridge, Selwyn College MS 108 L.1.) located in Herefordshire (LP 7460). Note the use of schulleþ and schulen within the same sentence:

(5) þou schalt vnderstonde þat Poule wryteþ many epysteles to dyuerse men þat he turned to þe byleue, how þei schulen byleuen, & how þei schulleþ lyuen

‘You must understand that Paul writes many epistles to different people that he turned to the faith, about how they are to believe and how they are to live’ (Bible SNT(1); Paues Reference Paues1904: 47)

Figure 2. Regularized shall (eLALME)

The variation can also be ascertained by looking up the relevant LPs with the ‘User-defined Maps’ tool in eLALME. In total, plural forms of shall ending in -þ(e) or -t(h) are recorded in 75 LPs from 72 different localities.Footnote 9 Of these LPs, only seven have regularized forms to the exclusion of forms with -(e)n, -e or zero. Note, however, that no frequencies of the different forms are given in the LPs, and that there is no information about the syntactic or metrical environment. If some forms are due to rhyme or meter, for instance, this cannot be seen in the LPs. What the atlas does tell us is where regularized forms are recorded, and, of course, where they are not: as the map in figure 2 shows, regularized shall is not recorded north of a line running roughly from Birmingham to Ipswich (where plural forms in -eþ would be unexpected anyway), and is almost completely absent in the east Midlands texts surveyed by the editors. It may thus reasonably be described as a southern and southwest Midlands feature.

4.2 Can

In contrast to shall, only three isolated instances of can were found in the LAEME, in the three texts listed in table 3. To these three examples we may add an additional one from the Ayenbite of Inwyt (ayenbitet; British Library, Arundel MS 57), from a section of the text not included in the LAEME sample (and hence not included in the count in table 3).Footnote 10 I return to the examples from this text below. The two thirteenth-century examples from the LAEME corpus are given in (6)–(7):

(6) leteð ƿriten on one scrouƿe hƿat-se ȝe ne kunneð nout

‘Have written on a scroll that which you do not know.’ (Ancr. (Nero A.14); LAEME, neroart, f10r)

(7) Þus hit goþ bitwenen hem two þat-on seiþ let þat-oþer do

Ne cunneþ hey neuere bilinnen

‘And so it goes between the two [i.e. soul and body], the one says “don't”, the other “do”; they cannot ever cease.’ (Sayings St.Bern. (Dgb 86); LAEME, digby86mapt, f126ra)

Table 3. Regularized can in LAEME

Note that kunneð in (6) is a transitive verb meaning ‘know’, while in (7) it is used with modal function. It does not seem to make a difference for the inflection whether can is used as a ‘full’ verb or a modal, as the corpus findings discussed below also indicate.

Some doubts might be raised about the two attestations from the Ayenbite of Inwyt. The example from the LAEME corpus is given in (8):

(8) And þis boc , is more y-mad , uor þe leawede ; þa(n)ne uor þe clerkes , þet conneþ þe writinges

‘and this book is made more for the laypeople than for the clergymen, who know the writings’ (Ayenb. (Arun 57); LAEME, ayenbitet, f25r)

At first sight this would appear to be a clear example of regularized can. In both this and the other example, however, conneþ is followed by þe, leading Wallenberg (Reference Wallenberg1923: 60 n. 1) to conclude that this is merely a sandhi effect. Gradon (Reference Gradon1979: 52) is more cautious, noting that the prs.ind.pl of can is otherwise invariably spelt conne. Unfortunately, since this is the only MS, the evidence will have to remain inconclusive. What is clear from the LAEME, though, is that regularized can is only very sporadically attested in the Early Middle English material.

Turning to the later material from the three other corpora, regularized can shows up in more texts, though not nearly as many as regularized shall in the eLALME material. As mentioned in section 3, I searched the MEG-C, ICMEP and CMEPV for possible spellings of regularized can. The texts with relevant examples are listed in table 4 along with the dates and provenance of the manuscripts. The example from Add.Serm. was found in the ICMEP, the ones listed as PConsc.* in the MEG-C, and the rest in the CMEPV.Footnote 11 Note that because none of the three corpora is lemmatized, I was not able to extract all plural forms of can automatically as in the LAEME; however, it is clear from searches in some of the texts that prs.ind.pl -eþ usually co-occurs with forms in -en or -e/∅. Compare (9) and (10), from the same version of the Prick of Conscience:

(9) Suche men haueþe nede to lerne besyly Of oder þat conneþ more þan hy

‘Such men need to learn diligently / from others who know more than they do’ (PConsc.* (Laud Misc. 486); MEG-C, L7040, fol. 2v)

(10) Ther~fore hy cunne nouȝt knowe and se Perels þt hy schold drede and fle

‘Therefore they cannot recognize and see / perils which they should dread and flee’ (PConsc.* (Laud Misc. 486); MEG-C, L7040, fol. 3r–3v)

Table 4. Regularized can, later texts

On the other hand, a few texts appear to contain only regularized variants of can. In SLeg.Becket (Ashm 43), for instance, the only examples of prs.ind.pl can are the two regularized ones listed in table 4. Similarly, the excerpt of PConsc.* (Laud Misc. 601) in the MEG-C contains only a single example of conneþ and no other forms of can.

Some of the manuscripts where regularized can was found are surveyed and localized in the eLALME. The LP numbers of these are given in the next-to-last column in table 4. For texts not surveyed in the atlas the information about date and provenance was taken either from the editions or from other studies.Footnote 12 While this information may not be as reliable as the eLALME data, it at least gives us an indication of the general area where regularized can is attested: all the forms that can be localized are found in manuscripts from the southwest Midlands, precisely the area where the attestations of regularized shall are most numerous. That regularized can and shall show a significant overlap becomes even clearer if one looks up shall in the six eLALME LPs listed in table 4: all of these contain regularized plural forms, e.g. schulleþ in LP 6980. In other words, the presence of regularized can implies the presence of regularized shall, at least in those texts in the corpus which were surveyed by the eLALME editors.

4.3 May

Moving on to the third and final modal, may, the evidence turns out to be much more sporadic. As Warner (Reference Warner1993: 101) notes, regularized may is recorded, though ‘apparently less frequently’ than shall and can. The form indeed appears to be very infrequent. The MED (s.v. mouen), which Warner refers to, cites only two examples of the form moweþ; the OED gives no examples; and as mentioned above, neither the LAEME nor the eLALME records any instances. Searching my three corpora, I identified a single example in the MEG-C and two in the CMEPV. To this one of the examples from the MED may be added, from a version of a text not included in any of the corpora, SLeg.Longinus (Corp-C 145) (see the MED, s.v. mouen v.(3), sense 2a). The references to these four examples along with the dating and geographical provenance are given in table 5.

Table 5. Regularized may, later texts

Example (11) is from one of the versions of the Prick of Conscience in the MEG-C. Apart from the short sample in the corpus, the manuscript is unedited, so I cannot say if this is an isolated instance in the manuscript. (12), from Glo.Chron.A (Clg A.11), is certainly the only example in this text; otherwise the text has mowe throughout. As (12) shows, the text also contains examples of regularized shall. The same holds for the other two texts surveyed in the eLALME; in other words, as in the case of can, the presence of regularized may in the material implies the presence of regularized shall.

(11) Ac þe skile whi he schal sitte þere Men moweþ finde bi þis sawe heere

‘And the reason why he shall sit there, one may find in what is said here.’ (PConsc.* (Laud Misc. 601); MEG-C, L6980, fol. 66r)

(12) Þe ssephurdes & þe ssep al so ⋅ ssolleþ to þe pine of helle ⋅ As god heiemen of þe lond ⋅ robbeors felawes beþ ⋅ Poueremen þat hii moweþ ouer ⋅ hii huldeþ as ȝe iseþ ⋅

‘The shepherds and the sheep, also, are going to the torment of Hell, when the good highmen of the country are the companions of robbers. Poor men that they have power over, they hold [or seize], as you see’ (Glo.Chron.A (Clg A.11), 7212–14; CMEPV)

Thus, with examples of regularized may – by no means an infrequent verb in Middle English – found in only four texts, I think we can safely conclude that the occurrence of this was very limited. One might even suspect that these are mere scribal errors, but here the provenance of the manuscripts must be kept in mind: the four examples of regularized may are from the same area as regularized shall and can, and as mentioned above, the three texts in table 5 which are localized by the eLALME all contain examples of regularized shall as well. If the examples of regularized may were only scribal errors, this overlap would have to be accidental. I think a more likely interpretation is that regularized may was a local innovation which for whatever reason failed to spread to a wider area. The fact that it occurs exactly once in the chronicle cited in (12) above, but is not otherwise used in the manuscript, suggests that it may have been copied into the extant version from the exemplar, but that the scribe did not otherwise use the form (i.e. a ‘show-through’ in the terms of McIntosh et al. Reference McIntosh, Samuels and Benskin1986: 13).

4.4 Interim conclusion

Having surveyed the occurrence of regularized modals in the atlases and corpora, we can now draw some conclusions about their distribution. The Early Middle English material in the LAEME contains examples of regularized shall and can. The former is found in five of the scribal texts in the atlas, the latter in three. With the exception of two uncertain examples of regularized can from the Ayenbite of Inwyt – which might be due to sandhi – all attestations are from the southwest Midlands.

The Late Middle English material contains more examples. Regularized shall is recorded in 75 LPs in the eLALME. Unsurprisingly, all of these are from the general area where -eþ was the regular prs.ind.pl suffix, but regularized shall is not evenly distributed in this area. Only very few examples are recorded in the east Midlands (see figure 2), so regularized shall may reasonably be described as a southern and southwest Midlands feature. The eLALME does not survey the morphology of can and may in the relevant parts of England, so these verbs were investigated with the help of three corpora. The occurrence of regularized can and may was shown to be more restricted than that of regularized shall: relevant forms of can were found in eleven texts, may in four. All of these are from the southwest Midlands, from an area running from Monmouthshire in the west to Oxfordshire in the east and from Warwickshire in the north to Wiltshire in the south. Regularized forms of these modals are thus both less frequent than regularized shall and restricted to a smaller geographical area. As mentioned above, their presence in the sources also always seems to imply the presence of regularized shall, at least in the texts surveyed in the eLALME, whereas regularized shall does not guarantee the presence of regularized can and may. The possible reasons for this asymmetry will be discussed in the following section.

5 Discussion: explaining the distribution

I now turn to the issue of whether we can explain the observed distribution of the forms and what the morphological regularization might tell us about the status of the modals in Middle English. It is evident that plural forms with -eþ must have spread through interparadigmatic analogy, as plural -eþ was not found anywhere else in the paradigms of preterite-presents (see section 2). The question is whether the basis for the analogy was the much larger class of regular verbs – the explanation favoured by Bryan (Reference Bryan1921) and Warner (Reference Warner1993) – or the ‘anomalous’ verb will, an alternative explanation also considered by Warner. I will suggest that the dialectal distribution of regularized modals makes the latter explanation more likely.

It is worth noting first that while I have referred to shall, can and may as ‘modals’ throughout, all three verbs also had certain non-modal (‘full-verb’) uses in Old and Middle English, with the meanings ‘owe’, ‘know’ and ‘prevail’, respectively (see e.g. the relevant entries in the MED). This could potentially be an argument for an analogical connection between these modals and the larger class of full verbs. In my corpus material, regularized can with the full-verb meaning ‘know’ is relatively frequent: of the 38 examples listed in table 4, 17 allow a non-modal interpretation.Footnote 13 Full-verb may ‘prevail’ occurs in one out of the four examples in the corpus, given in (12) above. However, I have found no examples of regularized shall with the full-verb meaning ‘owe’; the 43 attestations in the LAEME are all clearly auxiliary uses. So while it is of course possible that some Middle English speakers associated regular morphology with ‘normal’ full-verb use of the modals, this clearly was not a prerequisite for regularized morphology.

The ‘regular-verb’ explanation also fails to account for the distribution documented in section 4, i.e. the more frequent and more widespread occurrence of regularized shall and the strong presence of regularized forms in the southwest Midlands. I think that the most likely explanation for these facts is the alternative hypothesis discussed by Warner (Reference Warner1993: 101), i.e. that will was the main basis of the analogical extension of -eþ. There is both a functional and a formal reason why shall would be more susceptible to this analogical influence. First, while will and shall were clearly not completely synonymous, there seems to have been some functional overlap already in Old English. The two verbs are both recorded with predictive and intention meanings (see e.g. Bybee & Pagliuca Reference Bybee, Pagliuca, Giacalone, Ramat and Bernini1987: 112–14; Denison Reference Denison1993: 304; Wischer Reference Wischer2008); they are also frequently used alongside each other in paraphrases of Latin future expressions in Ælfric's Grammar (see e.g. DOEC, ÆGram 247.13 or ÆGram 252.7). While this does not mean that the two were interchangeable, it implies that they were often found in similar environments and that there was a degree of ‘functional contact’ (Bryan Reference Bryan1921) between them.

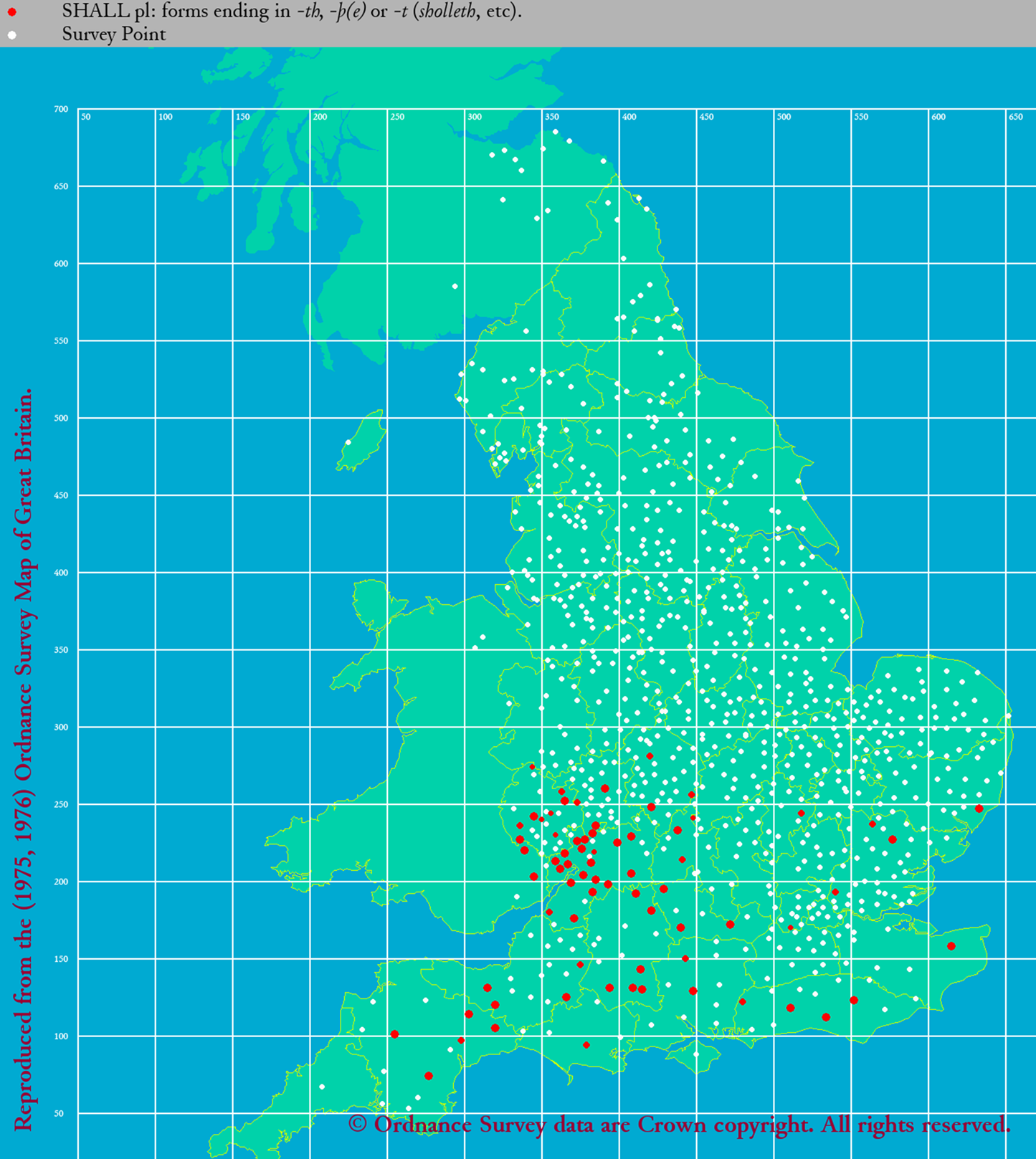

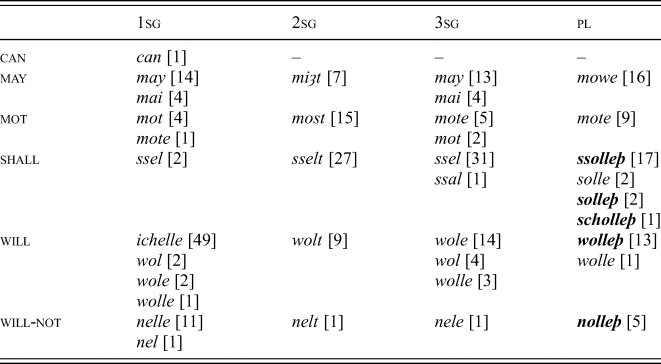

The formal reason was a sporadic sound change in Early Middle English which caused the plural forms of the two verbs to become more similar in some dialects. In Old English the two have different stem vowels: will has the prs.ind stem wil(l)-, while shall has the prs.ind stem sceal- in the singular and scul- (or sceol-) in the plural (see Hogg & Fulk Reference Hogg and Fulk2011: 303–5, 320–2; for the paradigms see also table 1 above). In some dialects in Early Middle English, however, the stem vowel of will was rounded, resulting in a stem variously spelt wol- or wul-, as indicated by the squares and dots on the map in figure 3).Footnote 14 This meant that in some dialects will and shall had the same stem vowel in the present indicative plural – but never in the singular. For an example of such a system, see table 6, which gives the prs.ind paradigms of the modals in corp145selt, the LAEME text with the most examples of regularized shall.Footnote 15 As the table shows, the plural stems of shall and will rhyme in this scribal text. A similar system is found in layamonAbt, where the plural forms of shall and will are consistently spelt with -u- (or -w-), and in egpm2t, which has three examples of plural will with -u- and one with -i-. In digby86mapt and jes29t, forms with -i- are in the majority, but digby86mapt also has two examples of wolleþ, and jes29t has five examples of wulleþ. In other words, all five LAEME texts with regularized shall contain examples of will with a rounded stem vowel in the plural.

Figure 3. will: stem vowels (LAEME)

Table 6. prs.ind paradigms of modals in CCCC 145 (corp145selt)

I would argue that the similarity of will and shall in the southwest Midland dialects was the main force driving the analogical extension of the prs.ind.pl suffix to shall. The two verbs had closely related meanings, but in the southwest Midlands they also had the same stem vowel in the prs.ind.pl, and the LAEME material strongly suggests that this was the area where regularized shall originated. From here the form expanded southwards to other areas where prs.ind.pl -eþ was in use, resulting in the distribution recorded in the eLALME (see figure 2). In addition, will and regularized shall together exerted analogical influence on can and (to a lesser extent) may in the ‘core’ area in the southwest Midlands, resulting in the regularized forms found in the corpora. This innovation, however, failed to spread to a larger area. While this scenario of course cannot be proved, I think it offers a better explanation of the observed facts than a more general appeal to the ‘verb-like’ nature of the Middle English modals.

To sum up this discussion, I think we can safely conclude that there was no general tendency for the Middle English modals to develop regularized plural forms: the development was only possible in some dialects, and even here the change mainly affected shall, as demonstrated in section 4. I have argued that analogical influence from the ‘anomalous’ verb will is the most likely explanation for the distribution observed in the Middle English material. Hence, while the ultimate result of the development was that some of the modals came to look more like regular verbs (as noted by Fischer Reference Fischer2007: 171 and Trousdale Reference Trousdale, Brinton and Bergs2017: 108), the cause of the change must be sought elsewhere.

6 Conclusion

This article has taken a closer look at an aspect of Middle English morphology which has received only sporadic attention in the literature. Using the linguistic atlases LAEME and eLALME and a number of corpora, I have attempted to map the distribution of regularized plural forms of shall, can and may. It was shown that the first of these is the most frequent one, followed by can and may in that order. Apart from two uncertain examples in the Ayenbite of Inwyt, the regularized forms of can and may are all attested in the southwest Midlands, in the same area where regularized shall is first recorded. I have suggested that the most likely reason for this distribution is that will provided the basis for the analogical extension of prs.ind.pl -eþ. This of course cannot be proved, but unlike the alternative explanation – analogy with the much larger classes of weak and strong verbs – it explains both why shall was most affected and why the innovation spread from the southwest Midlands.

As discussed in section 2, the apparent regularization of some present plural modals has been taken as an indication that the modals in Middle English were still felt to be part of the larger class of verbs. In light of the material presented above, this interpretation of the Middle English situation appears less attractive. If the analysis proposed here is on the right track, the plural forms in -eþ provide no evidence for a close connection with the larger classes of weak and strong verbs, but rather with the ‘anomalous’ verb will. However, as the Middle English data show, the analogical pressure from will was clearly stronger on shall than on can and may, and there is no evidence that the modal mot was affected at all. Each modal verb thus has its own inflectional history, as it were, and the Middle English modals did not yet behave as an entirely coherent class, at least not with respect to their inflectional morphology.

The above discussion, I hope, also provides an example of the value of digital linguistic atlases like LAEME and eLALME. By mapping historical texts in space, these resources make it possible to see connections between linguistic developments which one might overlook if only relying on text editions or electronic corpora. The atlases thus offer us the opportunity to gain many new insights about developments in Middle English – even concerning a well-researched topic like the history of the modals.