Political institutions derive their power in large part from the support of those whom they govern. Thus, an understanding of public attitudes toward how actors within political institutions should behave is critical for understanding institutional power (Smith and Park, Reference Smith and Park2013; Lapinski et al., Reference Lapinski, Levendusky, Winneg and Jamieson2016; Reeves and Rogowski, Reference Reeves and Rogowski2016). In this study, we provide new evidence about the relationship between the American public and the judiciary by measuring public attitudes over how the judiciary should function. We focus our attention on the American public's attitudes over how judges use legal principles, the individual legal factors that structure judicial decision-making.

Legal principles are critical for understanding and explaining judicial behavior. Judges regularly ascribe a primary role to these principles in shaping their jurisprudence (e.g., Scalia, Reference Scalia1997; Breyer, Reference Breyer2005) and political scientists have illustrated the important role legal principles play in influencing judicial decision-making (e.g., Hansford and Spriggs, Reference Hansford and Spriggs2006; Bailey and Maltzman, Reference Bailey and Maltzman2011). These principles also regularly appear in media discussion of the American courts, as illustrated by New York Times coverage of then-Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett's “broad commitments to originalism and textualism” and Associated Press coverage of oral arguments in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization that highlighted the relevance of precedent, plain meaning, and the societal consequences of the decision.Footnote 1

Despite their importance, legal principles have received relatively little attention in studies of public opinion toward the judiciary; we contribute theoretically and empirically to an emerging literature on this subject (e.g., Gibson and Caldeira, Reference Gibson and Caldeira2009b; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Persily and Ansolabehere2011; Farganis, Reference Farganis2012; Krewson and Owens, Reference Krewson and Owens2021, Reference Krewson and Owens2023). We draw upon data from a nationally representative survey of over 2300 Americans conducted at the beginning of the Supreme Court's October 2017 term to explore the nature of these views. Respondents answered a novel battery of questions designed to measure their attitudes over how Supreme Court judges apply legal principles to constitutional cases.

Our analysis reveals that Americans’ attitudes over how judges apply legal principles follow predictable patterns that mirror how these attitudes are arranged among political elites. First, we find strong support across all Americans for legal principles that are well-established and broadly accepted in the legal academy as important for judges to consider in their decisions, such as adherence to precedent. This near-universal support reflects the high esteem these legal principles hold in the eyes of judges, politicians, and legal commentators of all political stripes. However, we find clear differences across ideological lines in attitudes toward less traditionally accepted principles of judging, such as considering public opinion. These ideological divisions reflect the differences in attitudes among political elites, with liberals considerably more supportive of the use of these non-traditional principles than conservatives. Importantly, we find that increased knowledge of the Supreme Court magnifies these political differences, providing support for our theoretical argument that as individuals are exposed to elite political arguments about these principles, politics becomes a more important determinant of an individual's views over their use. An experimental analysis reveals that when evaluating case outcomes, (dis)agreement between an individual's own attitudes over the legal reasoning judges use and the legal reasoning given by judges leads to (decreased) increased specific support for that outcome. We also find limited suggestive evidence that the use of popular principles is associated with higher evaluations of judicial legitimacy.

Our study provides new insight into the relationship between the American public and the judiciary. While this is not the first study to measure Americans’ attitudes about legal concepts, we combine a theoretical framework grounded in the role political elites play in informing Americans about judicial policymaking with a methodological approach that measures attitudes toward individual legal principles. So doing, our study presents a comprehensive picture of the structure, sources, and consequences of Americans’ attitudes toward an essential component of judicial behavior.

The political nature of the attitudes we measure showcases the integral role politics plays in shaping attitudes toward the judiciary and reveals the intimate connection between law and politics in the eyes of the American public. Even evaluations of putatively apolitical legal principles are shaped by an individual's politics, highlighting the fundamental role of politics in shaping American attitudes toward the courts. Thus, we contribute to growing branches of scholarship that reveal the important role of elites in shaping attitudes toward the judiciary (e.g., Clark and Kastellec, Reference Clark and Kastellec2015; Armaly, Reference Armaly2018) and illustrate how political views structure evaluations of the courts (e.g., Swanson, Reference Swanson2007; Bartels and Johnston, Reference Bartels and Johnston2013; Christenson and Glick, Reference Christenson and Glick2015). That these attitudes can shape support for case outcomes and legitimacy shows that legal principles play a substantively important role in evaluations of the judiciary. In this way, we provide insight into the criteria the public uses to assess whether judges behave in a manner that preserves and enhances judicial legitimacy (Gibson and Caldeira, Reference Gibson and Caldeira2011; Farganis, Reference Farganis2012).

1. Attitudes toward how institutions and courts should behave

Political institutions, including unelected judiciaries, rely on the support of the governed as a source of political power. With no electoral mechanism to confer legitimacy on these courts, judges must be attentive to the standing of the courts in the public's eye. Scholars have explored the factors related to legitimacy evaluations, showing that legitimacy is associated with greater familiarity with the courts (Gibson and Caldeira, Reference Gibson and Caldeira2009c), fundamental values such as support for democratic norms (Caldeira and Gibson, Reference Caldeira and Gibson1992), and how political elites talk about the courts (Nicholson and Hansford, Reference Nicholson and Hansford2014; Clark and Kastellec, Reference Clark and Kastellec2015; Rogowski and Stone, Reference Rogowski and Stone2021). This research agenda does not provide, however, a detailed examination of what Americans want their judges’ behavior to be like while in office. For example, while we know that the public values judges who apply the law when making decisions (e.g., Sen, Reference Sen2017), this is a relatively general measure of views toward judicial behavior. There are a wide set of legal principles judges employ, and scholarship provides little insight into the public's attitudes over their use (with a few exceptions [e.g., Greene et al., Reference Greene, Persily and Ansolabehere2011; Krewson and Owens, Reference Krewson and Owens2021], which we discuss further below). This contrasts with a literature that directly explores how the public wants political officials to behave in other institutional settings (e.g., Gelpi, Reference Gelpi2010; Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2014; Lapinski et al., Reference Lapinski, Levendusky, Winneg and Jamieson2016; Reeves and Rogowski, Reference Reeves and Rogowski2016).

Existing scholarship offers insight into what these views might be like. Americans reward judicial nominees who are experienced, qualified, open about their political views, ideologically proximate, and share their descriptive characteristics (Sen, Reference Sen2017; Chen and Bryan, Reference Chen and Bryan2018; Kaslovsky et al., Reference Kaslovsky, Rogowski and Stone2021; Rogowski and Stone, Reference Rogowski and Stone2021). Support for individual Court decisions and Court legitimacy can be shaped by the alignment between an individual's ideological preferences and Court rulings (Swanson, Reference Swanson2007; Bartels and Johnston, Reference Bartels and Johnston2013). Evidence from judicial elections suggests that voters accept and support judicial candidates taking political stances, though campaign activity that is too political can erode court support (Gibson, Reference Gibson2012). In their study of legal realism, Gibson and Caldeira (Reference Gibson and Caldeira2011) find that Americans view judges as “principled in their decisionmaking” (209) and that these views are critical to the maintenance of judicial legitimacy, but we know little about what principles the public might have in mind. Similarly, Farganis (Reference Farganis2012) shows how Court opinions rooted in legalistic justifications can improve judicial legitimacy, but does not study what particular legal arguments or principles might be used in such a justification. While this scholarship does not directly ask Americans how they want their judges to behave, these studies provide evidence that the public expects judges both to base their rulings on legal principles and act in service of ideological goals.

Cues from political elites should also play an important role in shaping how Americans evaluate judicial behavior. A large literature details the importance of elite cues (e.g., Conover and Feldman, Reference Conover and Feldman1989; Chong and Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007). In political domains like the judiciary where individuals lack other sources of nuanced knowledge about the institution and its processes, elite cues play a particularly important role in shaping mass attitudes. Scholarship shows the impact media coverage can have on how the public evaluates the judiciary (Hoekstra and Segal, Reference Hoekstra and Segal1996; Zilis, Reference Zilis2015) and reveals that cues and messages from partisan elites influence individual attitudes toward judicial nominees, candidates, and rulings (Squire and Smith, Reference Squire and Smith1988; Nicholson and Hansford, Reference Nicholson and Hansford2014; Rogowski and Stone, Reference Rogowski and Stone2021).

2. New data on Americans’ expectations of judicial behavior

In this paper, we interrogate the American public's attitudes over an integral dimension of judicial behavior: the legal principles judges employ when making decisions. By “legal principles,” we refer to the factors that judges and legal scholars argue structure judicial behavior on the bench; for the purposes of this study, we focus on constitutional interpretation. Legal principles are regularly discussed by political elites in coverage of Supreme Court cases and in discussion of Supreme Court nominees, the two instances in which the American public is most often exposed to elite communication about the federal judiciary. For example, all 28 front-page New York Times stories on constitutional Supreme Court cases from 2010 to 2014 described the reasoning behind the decision given by the justices, often giving multiple types of rationales and noting the justifications used both by the majority and by dissenting justices.Footnote 2

The commentary that surrounds Supreme Court nominations further highlights the weight political elites place on a justice's approach to the law. In nominating Neil Gorsuch to the Court, President Trump lauded him as someone “who loves our Constitution and someone who will interpret [our laws] as written” while Senator Jeff Flake championed Gorsuch's commitment to legislative deference.Footnote 3 These statements reflect broader patterns in how politicians and the media communicate about Supreme Court nominees. Roughly 25 percent of all Senator press releases and 20 percent of network news transcripts about Supreme Court nominees directly reference a principle of judging.Footnote 4 Furthermore, approximately 11 percent of questions that Senators ask of Supreme Court nominees during Judiciary Committee hearings are about principles of judging, with these patterns remaining relatively constant across the past six decades (Collins and Ringhand, Reference Collins and Ringhand2013: 103, 131–33). The discussion of legal principles happens at similar rates to other important topics.Footnote 5

Previous studies provide insight into the public's attitudes toward judges’ use of the law. Farganis (Reference Farganis2012) shows that justifying a decision by referencing religious values leads to lower Court loyalty compared to using a legal argument based on precedent, although a justification based on public opinion did not perform worse than the legalistic argument. Greene et al. (Reference Greene, Persily and Ansolabehere2011) find that support for originalism is associated with conservatism and moral traditionalism. Krewson and Owens (Reference Krewson and Owens2021) employ a conjoint design to study whether a hypothetical judge's judicial philosophy shapes a respondent's support for the judge's nomination. The authors find that certain legal philosophies (originalism) are more supported than others (adherence to precedent, living constitutionalism) and that partisanship conditions these views, with Democrats more supportive of living constitutionalism and Republicans originalism (see also Krewson and Owens, Reference Krewson and Owens2023).

We build upon these studies by combining a unified theoretical and methodological approach to present a comprehensive picture of the structure, sources, and consequences of Americans’ attitudes toward how judges apply the law. While we are not the first study to measure Americans’ attitudes about legal concepts (e.g., Gibson and Caldeira, Reference Gibson and Caldeira2009b; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Persily and Ansolabehere2011; Krewson and Owens, Reference Krewson and Owens2021, Reference Krewson and Owens2023), we take a different theoretical perspective from previous work. As described further in the next section, we conceptualize these attitudes as about “principles” that are either “traditional” or “non-traditional” and theorize that Americans’ views differ across these ostensibly apolitical principles depending on elite cues and one's political sophistication. In this, our approach differs from research that has considered but ultimately not endorsed the view that elite cues drive the strength of attitudes toward the competing judicial philosophies of originalism and living constitutionalism (Krewson and Owens, Reference Krewson and Owens2023).Footnote 6 In our perspective, elite cues affect which principles Americans support, but more sophisticated Americans (especially liberal ones) may still support a range of principles. Thus, our theory helps elucidate the sources of these attitudes and highlights the interconnection of law and politics in the eyes of the American public.

In order to test our theoretical expectations, we measure attitudes toward ten individual principles of judging in a battery where respondents are free to rate multiple principles as important or unimportant rather than measuring attitudes over comprehensive judicial philosophies such as originalism and living constitutionalism that are in opposition.Footnote 7 This follows from how judges and politicians express support for a wide range of legal principles and fits with our theoretical expectations that Americans’ views, at least among those with more political sophistication, mirror those of elites. Our design allows us to capture possible heterogeneities in Americans’ views over these principles. By asking about a wide range of principles and considering the correlates of support for each one, we provide a rich descriptive account of how the American public evaluates the use of law in judicial decision-making and a direct test of our theoretical argument.

We also investigate the consequences of holding these views for evaluations of the decisions the Supreme Court makes, focusing on lower-profile cases. As judicial decisions are typically described in terms of the legal principles we measure, this allows us to directly test the importance of the attitudes we measure and complements existing scholarship that explores the role judicial philosophies play in shaping evaluations of prospective judges and decisions on high-salience issues such as abortion and affirmative action (Krewson and Owens, Reference Krewson and Owens2021, Reference Krewson and Owens2023).

2.1 Measuring attitudes toward legal principles

Among legal scholars, there exists considerable disagreement concerning the appropriate principles of judging. However, there are some principles that are widely accepted, at least in some form, by judges and political elites and are frequently discussed in the popular press. We refer to these principles as “traditional” legal principles, to denote their near-universal acceptance by judges and elites as important to use when interpreting the Constitution.

There is widespread agreement among jurists that text, history, and precedent are relevant factors to consider in constitutional interpretation. One common tool is the consideration of the original meaning of the constitutional text. Some judges, especially self-proclaimed originalists, have placed a primary emphasis on the principles of original intent (Bork, Reference Bork1971) or original public meaning (Scalia, Reference Scalia1997). Importantly, however, other judges—even those who have argued for a consideration of a broader array of factors (e.g., Breyer, Reference Breyer2005)—still support considering original meaning, even if they place a lesser emphasis on it. Consider, for example, Elena Kagan's statement in her Supreme Court confirmation hearings that “we are all originalists” in response to a question about constitutional interpretation.Footnote 8 Thus, even though judges may differ about the appropriate emphasis to be placed on these factors, there is little debate that these factors are at least appropriate to consider when interpreting the Constitution.Footnote 9 We emphasize that this agreement extends across political and ideological lines, with judges of all political stripes supportive of some consideration of these traditional factors in constitutional interpretation.

Other factors one may take into account when interpreting the Constitution, such as what the practical consequences of a decision would be or perspectives from other countries, generate more division among jurists. Consider, for example, Roper v. Simmons,Footnote 10 where Kennedy writes for the majority that “[i]t is proper that we acknowledge the overwhelming weight of international opinion against the juvenile death penalty” (578), leading Scalia to write at length against the consideration of international law in a dissent (622–28). These disagreements often divide jurists along political lines, with conservative judges typically opposed to the consideration of these less traditional factors (those beyond the traditional tools of text, history, and precedent) and liberals more open to their use.Footnote 11

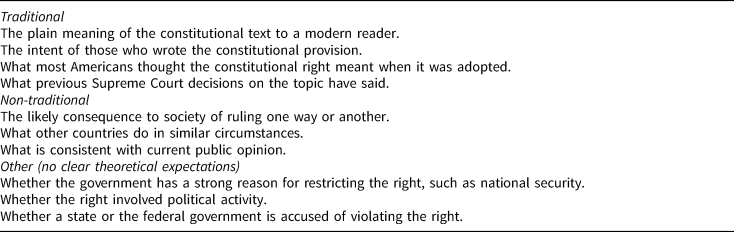

Table 1 shows the set of legal principles we focus on in our study.Footnote 12 Some of these principles are what we refer to as widely supported “traditional principles,” while we refer to less widely accepted principles that divide jurists and elites along political lines as “non-traditional principles.” In addition, we asked about some additional principles which do not fall into the “traditional” category but for which we did not have ex ante hypotheses about how political attitudes would be related to responses (the “other” category). By asking about a wide variety of principles, we are able to provide a rich descriptive account of Americans’ views on judging. Of course, there are a broad array of factors that could enter into judicial decision-making in constitutional cases. Our decision rule in choosing the principles we included in our survey was to ask about some of the most salient of these principles, both in the legal community and in political discussion.Footnote 13

Table 1. Survey battery: principles of judging in constitutional cases

Note: Questions asked in the October 2017 Harvard/Harris Poll. Respondents evaluated the importance of each of these principles for Supreme Court judges on a four-point scale. Response options were very important, somewhat important, not very important, or not important at all.

We recognize that legal principles are not a topic of everyday conversation for the majority of Americans. However, we believe that our measurement strategy allows us to capture meaningful attitudes toward the use of these principles. First, we attempted to avoid unnecessary jargon in constructing the language we used to measure these attitudes (e.g., we explained the concept of precedent rather than simply using that word). Second, legal principles—while unlikely to be often discussed by ordinary Americans—are regularly invoked by political elites when discussing cases and prospective judicial nominees, as the examples of this behavior we provided above illustrate. We therefore expect Americans, especially those who are politically attentive, to have been exposed to these concepts in political coverage of the judiciary. Third, existing studies have found that Americans hold meaningful and predictable attitudes toward broader judicial philosophies (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Persily and Ansolabehere2011; Krewson and Owens, Reference Krewson and Owens2021).

2.2 Elite rhetoric and attitudes toward judicial principles

To develop expectations for how Americans’ attitudes toward these principles are arranged, we emphasize the role of political elites, in contrast to scholarship that either remains agnostic (Krewson and Owens, Reference Krewson and Owens2021) or considers but ultimately does not endorse the role of elites in shaping attitudes toward the law (Krewson and Owens, Reference Krewson and Owens2023).Footnote 14 We expect that attitudes toward principles of judging are particularly likely to be shaped by political elites. These are a class of views that are relatively sophisticated, even compared to other attitudes toward the judiciary, such as support for the Supreme Court or a judicial nominee. This means that the average individual likely must rely on elite cues to develop attitudes toward the use of legal principles.

Elite attitudes toward legal principles are intimately related to politics and ideology. Those judges who advocate focusing exclusively on the more traditional principles of judging—like Justice Scalia and Robert Bork—tend to have conservative political views, while those judges supportive of using non-traditional legal principles—like Justice Breyer and Goodwin Liu (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Karlan and Schroeder2010)—tend to have liberal political views. Additionally, liberal and conservative elected officials also talk about principles of judging in different ways. While both conservative and liberal elites tend to emphasize traditional legal principles, liberal elites also espouse the use of non-traditional principles. For example, in confirmation hearings, Republicans spend a considerably greater proportion of their time asking questions related to judicial restraint and original intent than Democrats, indicative of the greater relative emphasis conservative elites place on these principles of judging than liberals.Footnote 15

Given how elites think and communicate about the legal principles used in judicial decision-making, we expect to see two patterns in American attitudes toward these principles. First, nearly all political elites and judges profess some support for the traditional legal factors. For this reason, we expect all Americans to evaluate positively the use of these legal factors by judges. Second, we expect political divisions in how Americans evaluate what we call non-traditional legal principles. Given the stark differences in levels of support for these principles between conservative and liberal political elites, we expect a similar pattern of divergence among members of the American public. We expect that these differences will be magnified among more politically knowledgeable respondents. These individuals are most likely to have been exposed to and internalize the elite political divisions over the use of these principles. In addition, these are the most likely respondents to understand the political ramifications of judicial behavior, and thus to make the connection between their own personal politics and how judges behave.

To investigate the public's attitudes over the legal principles that judges employ when ruling on cases, we included a module of questions in the October 2017 Harvard/Harris Poll, a nationally representative survey of 2305 American adults that measured their attitudes toward a range of questions related to American politics. Survey responses were collected between 14 and 18 October.Footnote 16

We measure individuals’ views on the principles upon which judges make their decisions with the battery of ten questions shown above in Table 1.Footnote 17 To do so, we first present respondents with the statement, “You will see a series of principles Supreme Court justices may use when deciding cases about constitutional rights, such as freedom of speech, equal protection under the laws, or the right against self-incrimination. For each, please state whether you think the principle is very important, somewhat important, a little important, or not important at all.”Footnote 18 $^,\;$![]() Footnote 19 Then, evaluations of the ten principles (in a random order) followed. Afterward, we asked respondents about their ideology as well as their knowledge of the Supreme Court.

Footnote 19 Then, evaluations of the ten principles (in a random order) followed. Afterward, we asked respondents about their ideology as well as their knowledge of the Supreme Court.

2.3 Americans’ attitudes over the use of judicial principles

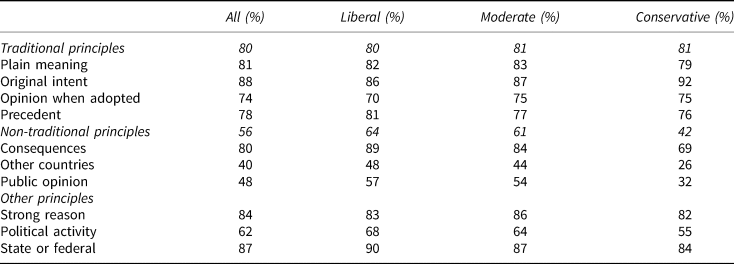

We begin by presenting the descriptive patterns in Americans’ evaluations of ten principles of judging. Table 2 presents the percentage of respondents who reported that each of the principles was very important or somewhat important. These descriptive results reveal that, consistent with our theoretical expectations, our set of traditional principles are viewed as very or somewhat important by nearly all Americans (74–88 percent, depending on the principle). The descriptive results also reveal that two of our non-traditional principles of judging are viewed as important by a minority of Americans, the role of contemporary public opinion (48 percent) and what other countries would be likely to do on the case (40 percent); the third, considering the societal consequences of a decision, was viewed as important by 80 percent of Americans. Consistent with our expectations, we see a divergence between conservatives and liberals in support for the use of non-traditional principles. While respondents who identify as conservatives espouse a relatively traditionalist view of the use of principles of judging (81 percent average importance), they view the non-traditional principles as much less important (42 percent average importance). Liberals share this appreciation for the use of traditional principles (80 percent), but they also are supportive of a relatively more non-traditional approach to judging than conservatives (64 percent), with a 22-point gap between liberals and conservatives on these principles.

Table 2. Percentage of respondents rating a principle as important

Note: Respondents evaluated the importance of using each of these principles for Supreme Court judges on a four-point scale. Response options were very important, somewhat important, not very important, or not important at all. Values are weighted to account for respondents’ likelihood of appearing in the survey.

We also find that our classification of principles into traditional and non-traditional groupings reflects the results of a factor analysis.Footnote 20 This is evidence that Americans’ attitudes toward principles of judging can be understood by grouping these principles into traditional and non-traditional sets. In a series of additional analyses that we present in the Appendix, we investigate how the public's attitudes toward the use of these legal principles varies across a set of other politically relevant characteristics, including race, gender, education, and income.Footnote 21

3. Sources and consequences of views on principles of judging

In the previous section, we provided evidence that the American public structures their attitudes toward principles of judicial decision-making along traditional and non-traditional lines. In the following sections, we investigate the source and consequences of these attitudes. First, we use our nationally representative survey data to explore the associations between a respondent's ideology and knowledge of the Supreme Court and their support for traditional and non-traditional principles. The patterns we uncover here will provide evidence as to how Americans’ personal politics and likelihood of exposure to elite discussion of these principles shape their views toward how judges behave on the bench. Second, we employ an experimental design to understand the consequences of supporting these principles for evaluations of judicial behavior. We investigate the degree to which views over the use of these principles shape evaluations of Supreme Court decisions above and beyond the role of an individual's political preferences. This allows us to understand how these attitudes operate in political context and illustrates the practical consequences of the attitudes we measure.

3.1 Politics, knowledge, and attitudes toward principles of judging

In this section, we more systematically investigate whether Americans’ political preferences are associated with attitudes over the use of legal principles. Our theory leads us to expect that Americans of all political stripes will evaluate the use of traditional principles in favorable terms. However, we predict that conservatives will support non-traditional principles of judging less than liberals, following the pattern we see among political elites and judges who espouse these views. Furthermore, we expect that these differences will be magnified among more politically knowledgeable respondents (but cf. Krewson and Owens, Reference Krewson and Owens2023).

In our analysis, we conduct separate linear regressions of a respondent's support for each of our ten principles of judging on indicators for respondents’ ideological preferences, coded as conservative, moderate, or liberal.Footnote 22 Our outcome variables range from 0 to 1, with the four importance ratings scaled equidistantly.Footnote 23 Our results are not sensitive to our model choice; we obtain substantively similar results using ordered logistic regression models.Footnote 24 We measure respondents’ knowledge of the Court using a seven-point scale that notes the number of correct answers to a series of factual questions about the Court; a fifth of respondents answered all seven questions correctly, nearly half of respondents answered four to six questions correctly, and the remaining 31 percent answered zero to three correctly.Footnote 25 We include this measure of knowledge and an interaction between knowledge and a respondents’ ideology in our models. Interacting the knowledge variable with respondents’ political characteristics allows us to test our expectations about whether more knowledgeable individuals adhere more closely to the principles favored by elites who share their political views.Footnote 26 If so, we expect to see increased differences between conservatives and liberals in how they evaluate non-traditional legal principles, but not traditional principles, as judicial knowledge increases.

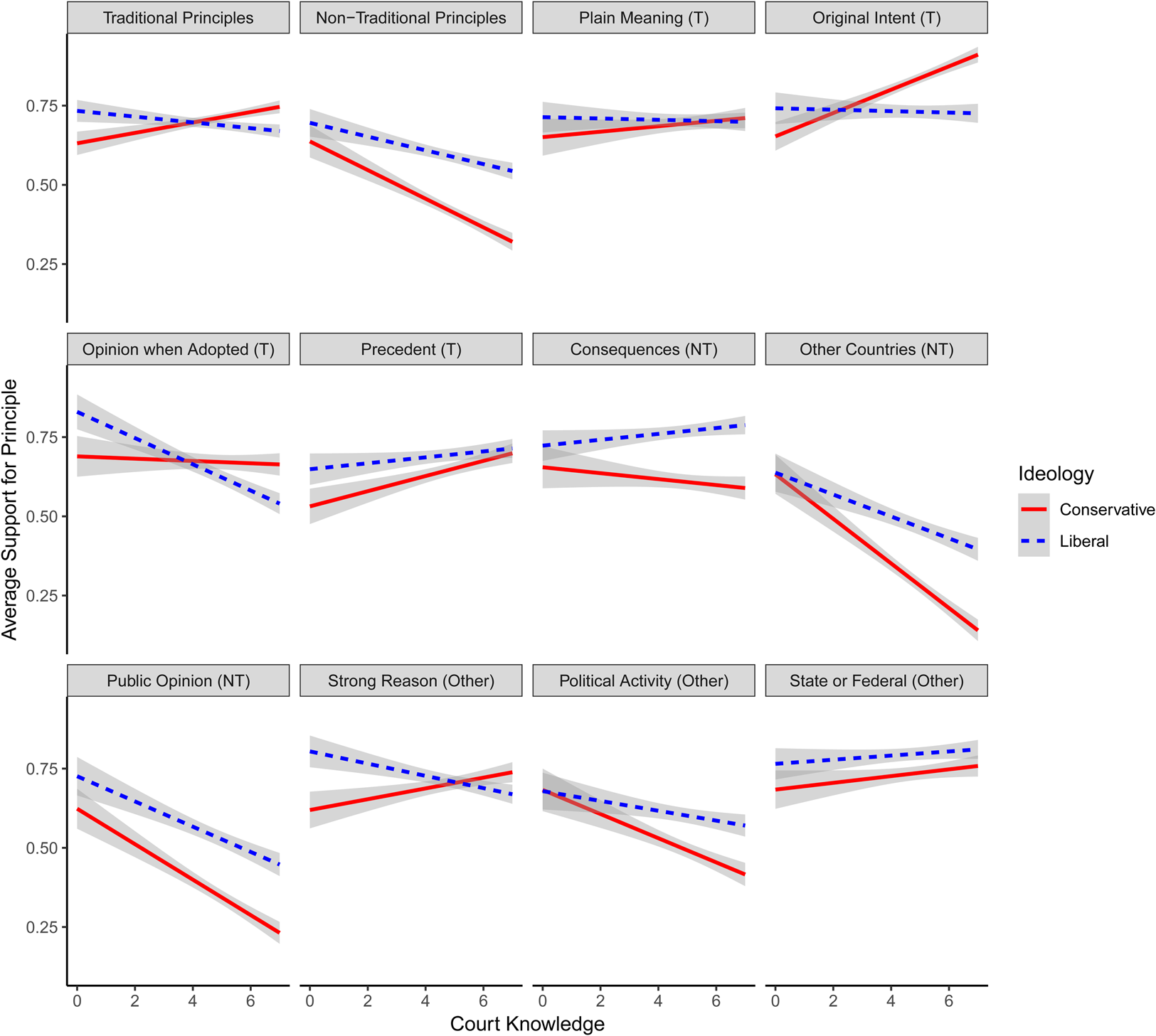

We present the results from our analysis in Figure 1, which presents predicted levels of support for each of our principles as a function of respondent ideology and knowledge about the Court. Our full regression models, as presented in Appendix Tables A-9 and A-10, include moderates and covariates. In addition to the ten individual principles, we also present results averaging across the traditional and non-traditional principles in the first two panels of the figure.

Figure 1. Politics, judicial knowledge and support for principles of judging.

Both individually and when averaging across principles, we find high and consistently positive attitudes toward the traditional principles of judging for all respondents—regardless of their ideological viewpoints. The positive evaluations of traditional principles among both conservatives and liberals hold across all levels of political knowledge. Indeed, on average, our full model predicts that liberal respondents are roughly 2.2 percentage points more likely to express support for traditional principles than conservatives. While there are some substantively small differences in support for particular traditional principles between liberals and conservatives at certain levels of Court knowledge, the broad takeaway is that Americans of all political stripes are generally supportive of the traditional principles of judging.Footnote 27 That we observe little effect of Court knowledge on views toward traditional principles is in line with our expectations, as both liberal and conservative elites are largely supportive of the use of traditional principles of judging. We note that individual principles exhibit greater variation than in the aggregate. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given conservative elite support for the judicial philosophy of originalism, conservatives increase in their support for original intent as a function of knowledge. Nevertheless, as expected, high-knowledge liberals continue to support the principle of original intent. The variation across individual principles illustrates the importance of the measurement of a wide variety of principles.

When turning to non-traditional principles, however, we observe a substantively significant divergence in how liberals and conservatives evaluate the use of these principles as a function of Court knowledge. As for the traditional principles, low-knowledge liberal and conservative respondents exhibit only substantively small differences in their evaluations of non-traditional principles (our model predicts an average difference of 7.9 percentage points for respondents who fell in the bottom third of Court knowledge). However, as knowledge increases, liberals and conservatives significantly diverge in their evaluations of the use of non-traditional principles. In particular, conservative respondents become considerably less supportive of the use of non-traditional principles as knowledge increases. Our model predicts that liberals who fell in the top range of Court knowledge (6 or 7 on the knowledge scale) were on average 19.3 percentage points more supportive of non-traditional principles than high-knowledge conservatives.Footnote 28 This divergence is approximately 2.4 times as large as the average difference in support for non-traditional principles among low-knowledge conservatives and liberals. Importantly, these differences in attitudes mirror the disparate attitudes toward these non-traditional principles among political elites.

3.2 The consequences of views on principles of judging

We have shown that Americans’ attitudes toward the use of principles of judging follow predictable patterns in line with those expressed by ideologically sympathetic elites. We now explore whether these attitudes have consequences for how Americans evaluate Supreme Court cases. We focus on cases as the principles we measure attitudes toward are the same principles that politicians and the media use to explain Court decisions. Evidence that these attitudes have predictive power in explaining views toward cases beyond an individual's personal politics would show legal principles serve as substantively important evaluative criteria that shape attitudes toward the American judiciary.

We investigate whether the use of particular legal principles in a Supreme Court ruling affects respondents’ support for the case. We expect that respondents will exhibit greater support for outcomes that justify the decision using principles the respondent ex ante supports the use of, and lesser support for outcomes using principles they do not support the use of. To study this relationship, we ran a survey on Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) with 872 respondents in September 2018, 426 of which were randomized into receiving this experiment.Footnote 29 We note that, although our respondents were not drawn from a nationally representative sample, research has shown that experimental studies conducted with MTurk samples uncover treatment effects that resemble those from more representative samples (Berinsky et al., Reference Berinsky, Huber and Lenz2012). Importantly for the purposes of our study, respondents’ views on principles of judging in our MTurk sample closely resemble those from our nationally representative October 2017 survey.Footnote 30 Furthermore, our sample's respondents are reasonably reflective of the American population.Footnote 31

To begin, each respondent evaluated the battery of questions to measure their attitudes toward principles of judging we presented above.Footnote 32 Then, respondents were randomized into receiving one of the two following case prompts about two actual Supreme Court decisions, one with a liberal outcome and one a conservative outcome.Footnote 33

• In Luis v. United States, the Supreme Court ruled that the government cannot freeze financial assets that belong to criminal defendants accused of committing a crime when the defendant wants to use that money to pay for a lawyer.

• In Town of Greece v. Galloway, the Supreme Court ruled that the invocation of prayer at a local legislative session does not violate the First Amendment's prohibition on governments establishing a religion.

We randomly assigned 20 percent of respondents into the control condition, and they received no further text in the prompt. The remaining 80 percent of respondents randomly received two of the following five principles that explain how the judges decided the case. We structure the treatment in this way for two reasons. First, including discussion of multiple principles helps us more closely mimic real-world Court opinions and popular discussion of them; justices typically rely upon multiple components of legal reasoning when making decisions and coverage of cases in the media is accompanied by descriptions of these multifaceted rationales.Footnote 34 Second, this design allows us to study a range of scenarios where respondents ex ante support none, one, or two the principles they received in the treatment.Footnote 35

Each sentence was structured as follows: “The majority opinion in the case argued that [reason one] and that [reason two].” The principles were as follows:

• the text of the [Sixth Amendment/First Amendment] clearly implies the right to [use one's property to pay for a lawyer/hold a prayer before a legislative session] (Plain Meaning)

• the writers of the Constitution did not intend to [prohibit the use of one's property to pay for a lawyer/prohibit legislative prayer] (Intent)

• the ruling has a firm basis in precedent from previous Supreme Court cases (Precedent)

• the ruling would lead to more positive consequences for society than a ruling that [allowed for freezing assets/prohibited legislative prayer] (Societal Consequences)

• the ruling was in line with the views of a majority of the American public (Public Opinion)

Our outcome variable is a binary measure of the respondent's expressed support for the Court's ruling in the case. We are interested in how the use of particular principles that may or may not be supported by a respondent are associated with support for the decision. To these ends, we operationalize our main explanatory variable as follows. If a respondent received an experimental prompt that contained two principles that he or she had ex ante rated as “very important” or “somewhat important,” we labeled the treatment as Both Important. Conversely, if the respondent rated both principles “not very important” or “not at all important,” we labeled the treatment as Neither Important. We classify a mixture of one principle rated as important and the other rated unimportant as Mixed Importance, with the control group as No Justification Given. This design allows us to uncover a causal estimate of the value that individuals place on courts employing legal reasoning that they support or oppose judges using.

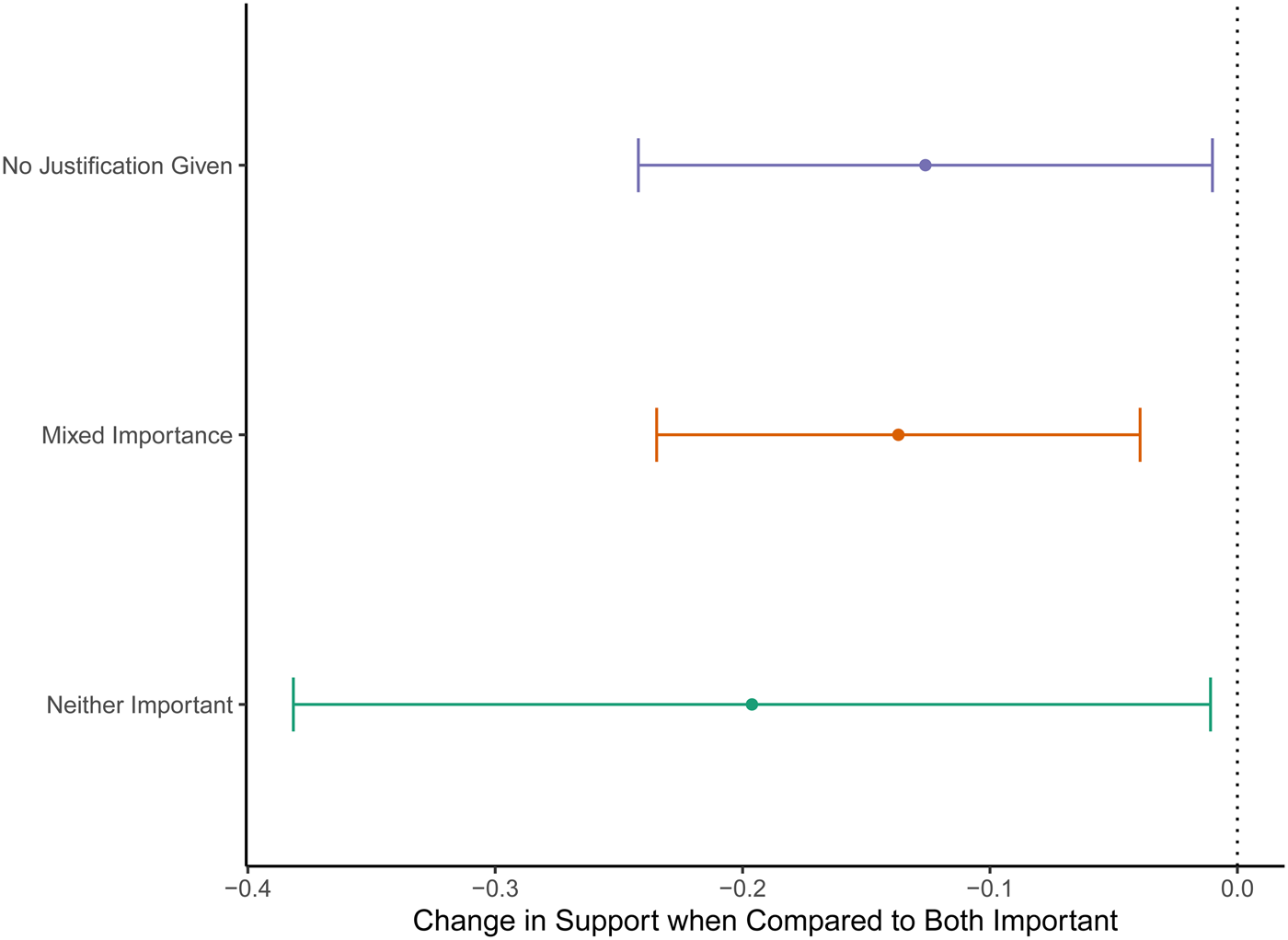

Figure 2 presents the differences in support for the Supreme Court's decision by treatment condition. We treat the condition where respondents received two principles they ex ante rated as important (Both Important) as the baseline; this helps us assess the consequences to the Court of relying upon principles that have greater or lesser degrees of support among the public. Our findings reveal that principles of judging shape evaluations of the cases at hand in substantively impressive ways. Compared to respondents exposed to two principles that they ex ante rated as important, respondents exposed to two principles they viewed as unimportant were 19.6 percent (p < 0.04, 95 percent confidence interval 1.1–38.2) less likely to express support for the Court's decision. Respondents in the Mixed Importance group (one important and one unimportant principle) express 13.7 percent less support than the Both Important group (p < 0.01, 3.9–23.5). Respondents in the No Justification Given group similarly express 12.6 percent lower support for the Court's ruling than those in the Both Important group (p < 0.04, 1.0–24.2), suggesting that using popular legal principles to justify decisions can boost support in comparison to providing no legal justification for these decisions. Our results are consistent when analyzing the data in a regression framework with respondent-level covariates, including the number of principles a respondent supported ex ante and demographic characteristics (see Tables A-15 and A-16).Footnote 36

Figure 2. Legal principles and support for court rulings.

These results are substantively impressive when benchmarked against the role individual ideology plays in shaping attitudes toward these decisions. In the Luis prompt, no distinguishable differences emerged in support for the decision across ideologies; in the Town of Greece prompt, liberal respondents were about 40 percentage points less supportive of the outcome than non-liberals. Thus, in certain cases without strong ideological divisions, like Luis, pre-existing support or opposition to legal principles explains considerably more variation in attitudes toward the case than ideology. But even in a case like Town of Greece with substantial ideological divisions, our regression results indicate that the effect of employing two principles the respondent ex ante supported is equal to roughly one-quarter to one-third of the effect of respondent ideology (see Table A-15). This illustrates that pre-existing views on how judges use legal principles have a substantively important impact on evaluations of case outcomes.Footnote 37

We also see suggestive evidence that the invocation of more popular principles is associated with higher perceptions of judicial legitimacy (Table A-18). Compared to when no justification is given, perceptions of legitimacy are higher when the respondent thinks both the principles that justified the decision were important.Footnote 38

4. Implications and discussion

In this paper, we show that the American public holds attitudes toward how judges apply legal principles when making decisions. Our nationally representative survey reveals that members of the public have measurable attitudes about judicial principles, and that these views map onto attitudes about the proper use of traditional and non-traditional principles shared by political elites. Importantly, a clear political dimension shapes these attitudes, with liberals considerably more supportive of the use of non-traditional legal principles in judicial decision-making than conservatives. This association with ideology is conditional, with the split greatest for respondents with high knowledge of the Court. We find that these attitudes are consequential, as individuals critically evaluate the principles that judges employ in case decisions in light of the principles they themselves value.

Our findings provide important new insight into the relationship between the American public and the courts. First, our findings illustrate the connection between politics and attitudes toward the American judiciary. This shows the consequences elite discussion of politics in the judicial context can have and accords with scholarship that has shown the politicizing effects of elite rhetoric in shaping attitudes toward the Court (Clark and Kastellec, Reference Clark and Kastellec2015; Sen, Reference Sen2017; Rogowski and Stone, Reference Rogowski and Stone2021). Second, our study helps provide insight into the particular nature of public opinion toward the courts, which are viewed in a uniquely positive light when compared with other political figures. While research by Gibson and Caldeira (Reference Gibson and Caldeira2011) and Farganis (Reference Farganis2012) suggests that the American public values principled legalistic justifications for decisions, there has been little empirical evidence as to what these principles might be. The results from our study provide evidence that the public holds views over particular legal principles, providing insight into the specific criteria the public uses to evaluate judicial behavior.

Our findings also shed light on the strategic incentives judges consider when using legal principles to frame their opinions. Our results indicate that the Court may be able to use legal principles to secure support for its rulings among those who might otherwise oppose them. This is conditional, however, on the Court choosing those principles that the American public actually supports being used. Indeed, if the Court justifies its decisions in terms of unpopular principles, it risks decreasing support for its decision. This suggests that while the Supreme Court can generate support for its decisions through the use of seemingly apolitical legal principles, its success depends on the legal principles it chooses to espouse. Given that the traditional principles are broadly popular with the American public, it is not surprising that both liberal and conservative legal elites continue to pay fealty to them in their opinion writing.Footnote 39

Nevertheless, it is important to note that judges are constrained by real-world conditions in their ability to credibly invoke these popular principles as justifications for their decisions. For example, opinions that overturn a major Supreme Court precedent (e.g., the Dobbs v. Jackson decision overturning Roe v. Wade) would struggle to appeal to stare decisis as core legal principle driving the decision. This highlights the constraints judges face in justifying their decisions to the public and the practical consequences for how opinion language affects the public's evaluations of Court decisions.

Our results also speak to a literature that has challenged the long-held view that Americans’ attitudes toward the judiciary's legitimacy are insulated from their views toward particular decisions (e.g., Swanson, Reference Swanson2007; Bartels and Johnston, Reference Bartels and Johnston2013; Christenson and Glick, Reference Christenson and Glick2015). In particular, we show how legal principles can be an important vehicle through which evaluations of Court legitimacy respond to individual decisions the Court makes. Beyond politics, we find that Court legitimacy is susceptible to changes as a result of individuals’ support or opposition to the legal principles contained in decisions. We thus show the American public places a value on the legalistic aspects of a Court decision, similar to scholarship showing that the public values procedurally fair decision-making (Baird and Gangl, Reference Baird and Gangl2006) and responds negatively to game frames (Hitt and Searles, Reference Hitt and Searles2018).Footnote 40

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2023.53. To obtain replication material for this article, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/X5PCNJ

Acknowledgments

We thank Shiro Kuriwaki, Alyx Mark, Michael Olson, Jon Rogowski, Meg Schwenzfeier, Amy Steigerwalt, and participants in workshops at Harvard University for helpful comments. We acknowledge the Harvard CAPS/Harris Poll for providing components of the data used in this project. The Harvard Experiments Working Group provided generous research support for components of this project. Previous versions of this paper were presented at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association and the 2018 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association.

Competing interests

None.