1. Introduction

The past few decades have witnessed an emergent trend in which the English language has become institutionally established as the medium of instruction (i.e., EMI) at a university level in many non-English-speaking countries and regions (Dearden, Reference Dearden2014). However, the promotion of EMI in higher education is found to be a cognitively complex and affectively contested endeavor (e.g., Dang et al., Reference Dang, Bonar and Yao2023; De Costa et al., Reference De Costa, Green-Eneix and Li2022; Hillman et al., Reference Hillman, Li, Green-Eneix and De Costa2023), where many university staff are pushed to take up EMI without adequate training and social support. In 2018, Macaro et al. (Reference Macaro, Curle, Pun, An and Dearden2018) published a seminal review article on EMI in Language Teaching, drawing a comprehensive picture of how EMI is envisioned, designed, and enacted in the classroom, curriculum, and policy levels in higher education settings across the globe. One critical and promising research direction, pinpointed by the review, is the strengthening of EMI teacher education, with a view to enhancing EMI teachers' pedagogical competence, facilitating classroom innovations and curriculum reforms, and ultimately engendering effective practices to support students' academic study and personal growth in specific disciplines (also see Yuan, Reference Xu and Zhang2020, Reference Yuan2023a).

In response to the call for more research on EMI teachers' professional development made by many EMI scholars (e.g., Macaro et al., Reference Lu2018), there has been an emergence of a wide range of initiatives and programs dedicated to preparing and developing competent EMI teachers (e.g., Bradford et al., Reference Bradford, Park and Brown2024; Dang et al., Reference Dang, Bonar and Yao2023; Lasagabaster, Reference Lasagabaster2022; O'Dowd, Reference O'Dowd2018; Sánchez-Pérez, Reference Sánchez-Pérez2020). To date, however, a survey of the EMI literature has revealed no systematic review of current empirical evidence on this significant topic in applied linguistics and higher education. The present critical reviewFootnote 1 thus attempts to fill the gap by systematically and critically examining the existing studies on EMI teacher development from 2018 to 2022. As scholars have made valuable attempts to look into how EMI teachers learn and develop in various forms (e.g., via formal training programs, collaborative projects, and individual reflections) during this five-year period, such literature constitutes the basis of the present review.

The significance of the review rests on the following aspects. First, based on a thorough analysis of the major themes in current empirical studies, our review sheds light on how different routes of EMI teacher education are designed and operationalized in a wide range of educational settings, and provides insights into the complexities surrounding EMI teachers' professional learning and the mediating factors that shape such learning at personal and contextual levels. Second, by presenting a comprehensive picture of EMI teacher development in higher education, our review can potentially be of value to EMI teacher educators by providing them with practical suggestions on how to take situated and effective action to help EMI teachers navigate their professional development in specific disciplinary and institutional contexts. For university management and policy/curriculum makers, the review also offers a better understanding of EMI policy ramifications, as well as generates suggestions for the design, implementation, and reform of EMI teacher development programs. Third, by conducting a methodological review and critique, the paper affords a critical analysis of the research trends and methods in the field and, subsequently, points out meaningful directions for future research on EMI teacher education.

2. EMI teacher development in higher education

Teacher development is conceptualized as a socially mediated process that involves continuous interactions between individual teachers and their sociocultural contexts, as the former seek to refine existing knowledge and construct new understandings within and across multiple sites (Borko, Reference Borko2004; Knight et al., Reference Knight, Tait and Yorke2006). Therefore, rather than constituting a linear process, teacher development takes place across temporal, spatial, and social boundaries in communities operating in accordance with differently nuanced discourses, histories, and cultural resources. For instance, teachers participating in training programs are frequently provided with the latest theoretical understandings and innovative teaching strategies to be applied in their instructional settings (Freeman, Reference Farrell2002; Peercy & Troyan, Reference Peercy and Troyan2017). They may also collaborate with their colleagues or university-based teacher educators through action research, leading to a shared repertoire of resources, practices, and insights aimed at addressing practical problems and promoting student learning (Yuan, Reference Xu and Zhang2020). Effective teacher development thus depends on creating customized opportunities and ongoing support for teachers to engage in hybrid practices that allow knowledge exchange, social engagements, and emotional guidance. Overall, teacher development is often acknowledged as a fluid, participatory activity situated within intersecting contexts that are both enabled and constrained by the structural conditions of various communities over time (De Costa & Uştuk, Reference De Costa, Li, Rawal, Schweiter and Benati2023).

EMI teachers are generally referred to as those who teach content-area courses (rather than the English language itself) through English in higher education (Yuan, Reference Yuan2023b). With the rapid increase of EMI programs in higher education contexts, the literature has reported a wide range of linguistic, sociocultural, pedagogical, and professional challenges for EMI teachers, particularly those who are non-native English speakers working in English-as-a-foreign language (EFL) contexts. We next briefly outline the common challenges faced by EMI teachers, in order to highlight the necessity of EMI teacher development.

First, EMI instructors often find teaching in EMI classes linguistically challenging, and many feel unprepared to teach in their second/foreign language (Hillman et al., Reference Gustafsson2023). Specifically, lecturers' language competence is regarded as one of the main obstacles to the successful implementation of EMI programs, as it is often connected to the proficiency level needed to teach discipline-specific academic content in a foreign language (Guarda & Helm, Reference Grant and Booth2017). The perceived low English competence of EMI teachers is likely to hinder their ability to employ appropriate discourse-specific language usage at lexical, syntactic, semantic, and other related levels that align with the academic conventions of a particular discipline (Richards & Pun, Reference Richards and Pun2022). This limitation can further impede their ability to either cover the content in sufficient depth or help their students apply the acquired knowledge in academic tasks in EMI classrooms. Moreover, since academic disciplines contain various language features and discourse practices (Lasagabaster, Reference Kubanyiova and Feryok2018), even instructors with high levels of general English proficiency may not be able to use appropriate instructional language or discipline-specific language to explain complex concepts (Metzger, Reference Martinez, Fernandes and Sánchez-Pérez2015).

Second, the linguistic challenges reported above are further complicated by social and cultural factors. For example, as one of the major objectives of EMI implementation is to attract international students, EMI classes are often populated by students who have diverse experiences and mixed abilities from different academic traditions (De Costa et al., Reference Dearden2021; Yuan, Reference Yuan2023b). Teaching in such a context therefore requires not only English proficiency and subject-specific expertise but also a heightened awareness of cultural differences that students bring to the learning process. For instance, Gundermann (Reference Guarda and Helm2014) pointed out that rather than being “culture-free” (p. 266), EMI instruction is often conflated with cultural diversity that requires EMI teachers to be equipped with intercultural sensitivity and communicative strategies, especially in heterogeneous classrooms where different cultures may potentially distort communication. Such intercultural demands thus make teaching in an EMI context even more challenging.

The third challenge faced by EMI teachers relates to pedagogy. For instance, one of the frequently reported challenges in EMI teaching is delivering disciplinary content with appropriate academic language (Goodman, Reference Goodman2014; Hu & Lei, Reference Hu and Lei2014). Such a challenging classroom expectation requires teachers to possess adequate pedagogical awareness and skills in language and content integration (Wang & Yuan, Reference Wang and Yuan2023). Although much variation is to be found depending on the context, EMI teaching is often undertaken by content teachers with high English language proficiency (Richards & Pun, Reference Richards and Pun2023). Some teachers may hold the misconception that EMI teaching is simply a matter of translating their previous teaching approaches and strategies in non-EMI contexts into English versions. Nevertheless, such direct borrowing without integrating language and content may lead to the teachers' under-preparation in delivering EMI courses and a reduction in the quality of teaching (Dang et al., Reference Dang, Bonar and Yao2023; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kim and Kweon2018). A viable approach for EMI teachers, under such circumstances, is to constantly infuse the acquisition of content with an awareness of disciplinary language, and experiment with a variety of learning activities in their specific fields to maximize their students' learning outcomes in both language and content (Yuan, Reference Xu and Zhang2020). This requires EMI teachers to engage in continuous classroom innovations and professional development initiatives to update their pedagogical knowledge.

The fourth dimension of reported challenges concerns EMI teachers' professional status, which is frequently interwoven with the aforementioned difficulties. One problem seems to be the lack of confidence, motivation, and self-efficacy among teachers. Tsui (Reference Tsui2018) reported that many teachers felt that they either lacked English proficiency to deliver EMI instruction or lacked self-efficacy in using English in their discipline instruction. Such a lack of confidence may cause a sense of vulnerability and insecurities in the teachers' self-perceptions (Doiz & Lasagabaster, Reference Doiz and Lasagabaster2018), which can have negative repercussions on their teaching. Additionally, some EMI teachers may also be concerned about the conflict between their professional identity as experts in their discipline (i.e., the authoritative figure) and their perceived lack of proficiency in a foreign language (i.e., English) (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kim and Kweon2018). Such identity tensions can result in emotional dissonance and social barriers between them and their students (Yuan, Reference Xu and Zhang2020).

To address such challenges, systematic and sustained support needs to be in place to help EMI teachers enhance their teaching quality. As Macaro et al. (Reference Macaro, Handley and Walter2019) proposed, it is particularly important to offer “more substantial training to ensure homogeneity and quality of EMI provision in tertiary education and set the pathways for professional development and a more global future” (p. 116). Presently, extensive research has been conducted exploring institutional practices, EMI teachers' attitudes, their learning process and gains, their assessment needs, and the overall effectiveness of EMI teacher development programs across a wide range of educational settings that span countries such as China (e.g., Chen & Peng, Reference Chen and Peng2019), Italy (e.g., Long et al., Reference Lauridsen and Lauridsen2019), South Korea (e.g., Bradford et al., Reference Bradford, Park and Brown2024), Spain (e.g., Morell et al., Reference Morell, Aleson-Carbonell and Escabias-Lloret2022a), Denmark (e.g., Dimova & Kling, Reference De Costa, Uştuk, De Costa and Uştuk2022), and others (see Dang et al., Reference Dang, Bonar and Yao2023; Sánchez-Pérez, Reference Sánchez-Pérez2020). Special issues have also been published (e.g., Ruiz-Madrid & Fortanet-Gómez, Reference Ruiz-Madrid and Fortanet-Gómez2022) to support EMI teacher development in the field of language and content integration. Along more practical lines, a growing number of language specialists, teacher educators, and institutions have also attempted to design and implement EMI teacher development programs with the purpose of improving EMI teachers' overall competence and ultimately facilitating the continuing development of EMI programs. Such EMI teacher education initiatives have taken various forms (e.g., training courses, short-term workshops, or collaborative partnerships), and have focused on different dimensions of EMI instruction and teacher development. For example, some training courses have relatively fixed content, such as the Cambridge Certificate on EMI Skills and the EMI Oxford Course (Martinez & Fernandes, Reference Martinez, Fernandes and Sánchez-Pérez2020). By contrast, other courses have conducted needs analyses to cater to and customize their content according to the specific needs of their lecturers and students (e.g., learning disciplinary terminologies, pedagogical approaches, and interaction strategies). Overall, there have been national and even international efforts to standardize EMI teacher development with a view, for instance, to define EMI teacher competencies and the issue of accreditation (Macaro et al., Reference Macaro, Handley and Walter2019). However, local educational contexts often prove to be more complicated than expected and thus require linguistic, social, and cultural details that merit attention during the process of EMI teacher development.

The recent progress reported above has motivated us to conduct the present review that synthesizes, analyzes, and critiques the current state of research and practices in EMI teacher development. Additionally, given the scant attention dedicated to EMI teacher development until recently, it is equally important to draw readers' attention to different methodological approaches adopted so far and map out future directions in terms of research topics and methodologies. This critical review is guided by three research questions:

1. What are the routes to EMI teacher development in higher education?

2. For each route, what are the reported gains and challenges for EMI teacher development?

3. What are the research methodologies used by the selected studies, and what are their strengths and limitations?

3. Research methods

3.1 Paper selection

Informed by the three research questions, we discussed and established a set of selection criteria for the proposed review. First, we decided that the topic of the literature search would be “EMI teacher development in higher education”. Therefore, studies focusing on EMI students, EMI instructional strategies, or those conducted outside higher educational settings were considered irrelevant and thus excluded. Second, the type of literature that we analyzed was confined to peer-reviewed journal articles because they generally undergo a rigorous review process, and thus represent a relatively high standard of inquiry. Consequently, other types of literature such as theses and dissertations, book chapters, and conference proceedings were excluded from our review. Third, the time window of the search was set in 2018–2022 (including articles of advanced online publication) to track the rapid growth of research literature in EMI teacher development following Macaro et al.'s (Reference Lu2018) seminal review paper.

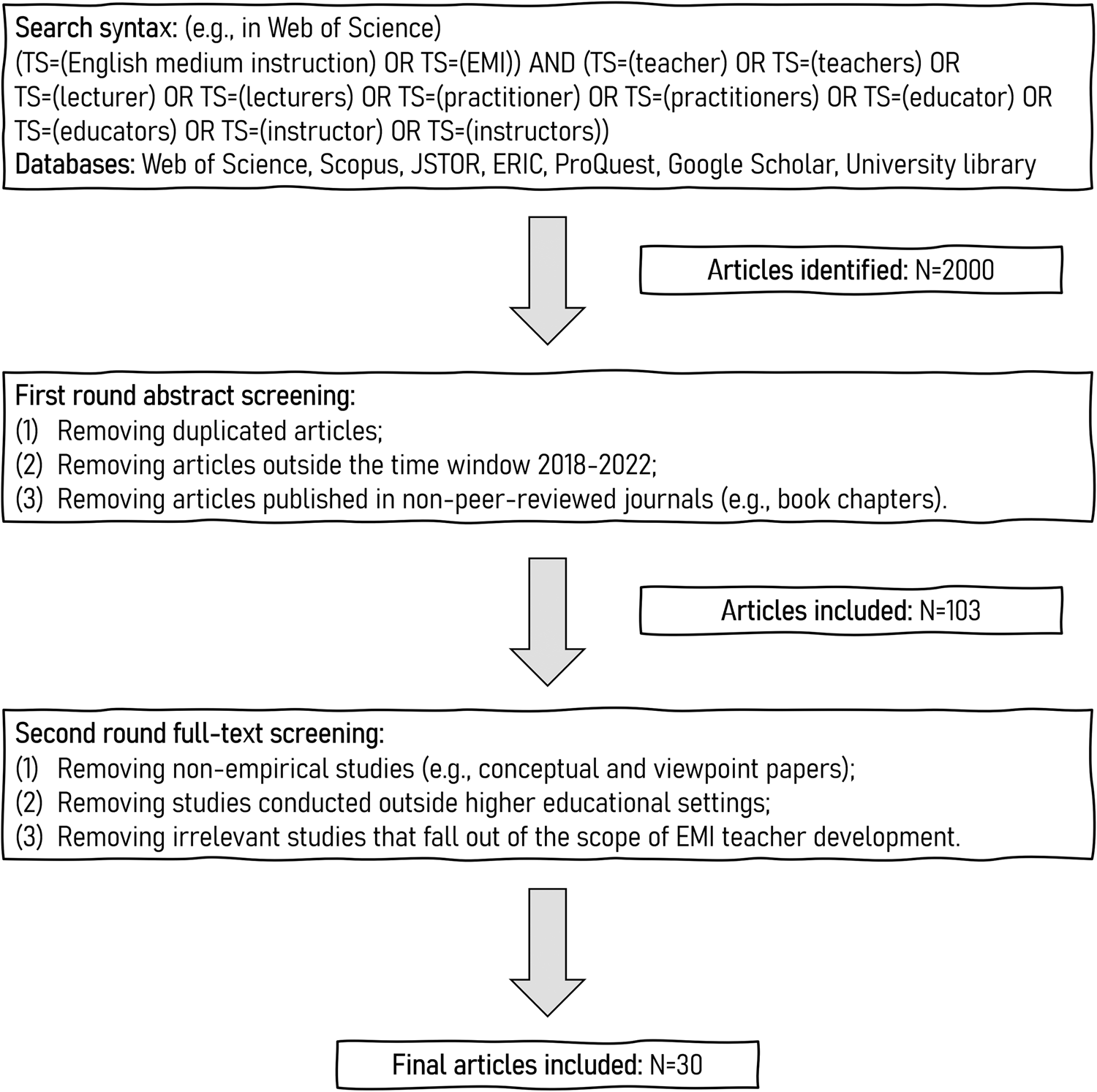

Using several keywords such as “English medium instruction”, “EMI”, “teacher education”, “teacher development”, and “instructor”Footnote 2, the research team searched for relevant articles in seven databases (i.e., Web of Science, Google Scholar, Scopus, JSTOR, ERIC, ProQuest, and the first author's university library). These seven databases were chosen based on a combination of the reference of similar published review articles (e.g., Macaro et al., Reference Lu2018; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan2022) and the research team's access to resources. Figure 1 depicts the process of article search and screening. As the flow chart shows, the first round of keyword searches yielded a total of 2,000 entries of relevant articles for possible inclusion. Then, two rounds of screening (first round abstract screening and the second full-text screening) conducted by the review team subsequently excluded 1,970 irrelevant articles, resulting in 30 journal articles that met the search criteria described earlier. Specifically, the first round of screening excluded duplicated articles, articles published outside the time window, and works published other than peer-reviewed journal articles. The second round of screening narrowed down the scope and focused more on the content relevance of the articles (e.g., empirical studies, higher education contexts, and concrete evidence of teacher development). In total, the screening process yielded 30 relevant journal articles that fell within the scope of our review, thereby creating a manageable database that can provide meaningful themes in accordance with our research objectives.

Figure 1. The literature search and screening process

To ensure the reliability and trustworthiness of the review, we followed the guidelines and features of systematic reviewing proposed by established EMI researchers (Gough et al., Reference Goodman2012; Macaro et al., Reference Macaro, Curle, Pun, An and Dearden2012). First, given that “a systematic review is always carried out by more than one reviewer” (Macaro et al., Reference Macaro, Curle, Pun, An and Dearden2012, p. 3), we formed a research team comprised of two educational linguistic experts and one doctoral student in applied linguistics. The team members engaged in constant discussions during the screening process to refine our selection of articles as well as the inclusion criteria and eventually decided on the final set of articles for the review. Our goal was to reduce reviewer bias as much as possible. Second, a transparent procedure – from search strategy to review protocol – was discussed and agreed upon by our team. Synthesis and appraisal of the shortlisted articles were conducted based on the empirical evidence presented by the articles. Third, the literature search and screening went through an exhaustive and reliable process by employing different search strategies in multiple databases. For example, to achieve analytic saturation, the research team formed several search syntaxes targeting different databases. Specifically, possible synonyms (e.g., teacher, instructor, lecturer, practitioner, and educator) were included in the syntax to avoid the omission of relevant articles.

3.2 Paper analysis

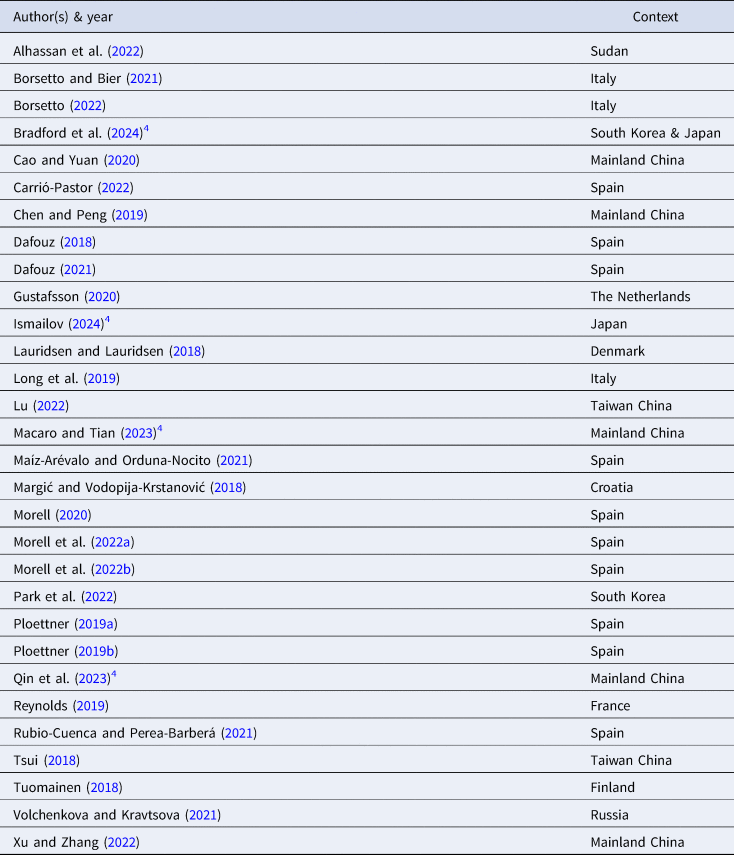

The 30 studies extracted were conducted in different educational settings, including Spain (n = 10), China (n = 7), Italy (n = 3), South Korea and Japan (n = 3Footnote 3), France (n = 1), Sudan (n = 1), the Netherlands (n = 1), Denmark (n = 1), Croatia (n = 1), Finland (n = 1), and Russia (n = 1) (see Table 1). Overall, the selected studies were mainly conducted in European and Asian contexts. Such a geographic distribution of EMI teacher development studies reflects the contemporary higher education reality that Europe and Asia are considered relatively mature and rapidly growing contexts for EMI (Shao & Rose, Reference Shao and Rose2024). At the same time, however, the absence of studies from Latin America strongly suggests that, moving forward, more research attention should be directed to the Latin American context.

Table 1. Contexts of the selected papers

With respect to data analysis, the contents of each paper were treated together as raw data for critical review. The first two authors carefully scanned and reviewed the studies, extracting and synthesizing the major issues and themes reported in them. They cross-checked and compared their findings in order to generate the major themes of the critical review. Meanwhile, the third author served as an advisor, providing professional suggestions, and engaging in ongoing discussions with the first two authors to enhance the validity and trustworthiness of the analysis.

Specifically, to answer the first research question, the abstract, introduction, and context reported in each paper were read, examined, and compared to generate the major routes to EMI teacher development in higher education. For instance, an author assertion such as “This study examines the impact of interdisciplinary teacher collaboration on English-medium instruction (EMI) teachers' professional development in higher education” (Lu, Reference Loughran and Hamilton2022, p. 642) led to a categorization of this paper into “teacher collaboration”. This stage of analysis yielded three major routes, namely, formal training, teacher collaboration, and self-initiated practice.

To address the second research question, the findings reported in each study were closely examined and categorized to identify the reported gains and challenges of EMI teacher development. For instance, the statement “ … by becoming more aware of I-R-F sequences the lecturer was able to more constructively facilitate class interactions … ” (Ismailov, Reference Ismailov2024, p. 3231) was coded as an example of “improved classroom interactions”, which led to the theme of “pedagogical improvements” together with comparable codes. Similarly, in the results section of Margić and Vodopija-Krstanović's (Reference Margić and Vodopija-Krstanović2018) study, the authors reported that “[s]ome of the weaker teachers mentioned that the programme had led them to question their ability to teach in English” (p. 36). This statement was extracted and coded as “teachers' self-doubt”, and further categorized into the theme of “the risk of increased negative emotions” as one reported challenge.

Regarding the third research question (i.e., research methodologies used by the selected studies and their strengths and limitations), the authors identified the research contexts, participants, and research design, and evaluated the data collection and analytic methods. All the identified information was further compared, contrasted, and synthesized to illustrate the main patterns of methodological concerns behind EMI teacher development. After addressing the three research questions, the research team engaged in a reflective discussion, along with the immersion of relevant literature, to provide insights into the implications and future directions of EMI teacher development.

3.3 Limitations

Admittedly, the method of paper selection reported above may contain several limitations. First, the relatively small number of studies reviewed (n = 30) excluded other relevant research works including unpublished theses and dissertations, book chapters, and the literature published outside the time window of 2018–2022. Second, although the review included several works published in bilingual journals (e.g., Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses), our research resources did not allow for a comprehensive review of the large number of research papers published in languages other than English (e.g., Chinese journals), and thus these studies were excluded during the selection process. Those excluded works are nevertheless valuable to the field and should be addressed in future review studies.

4. Findings

In this section, we present the synthesis and critical analysis of the 30 studies in the database in order to address our three research questions. We first present an overview of the three routes to EMI teacher development. For each route, we demonstrate a detailed illustration of the implementation of each study (e.g., project, duration, design, structure, and participants). Next, we describe major themes derived from the reported gains and challenges of each study. We then provide a methodological review with reference to the data collection and analysis methods of the selected studies.

4.1 An overview

The review identified three pathways for EMI teachers' professional development: formal training initiatives (n = 21), opportunities for teacher collaboration (n = 7), and self-driven practices (n = 2). Formal training initiatives represented the primary route to development through various forms, including institutional projects, structured workshops, short-term seminars, and longer-term interventions. Despite the diversity in terms of format and duration (see Table 2 for detailed information), these initiatives commonly entailed a predetermined curriculum carefully planned by universities at different levels. For example, Borsetto and Bier (Reference Borsetto2021) reported on a university project in Italy offering credited interactive courses on lecturing in English attended by over 200 faculty across seven years. Chen and Peng (Reference Chen and Peng2019) outlined a consecutive set of five-day intensive modules in mainland China concentrating on EMI conceptualization, language modification, instructional strategies, and microteaching.

Table 2. Formal training initiatives for EMI teacher development

Collaboration, which emerged as another promising route to EMI teacher development, was mediated through peer observations, course co-planning, and knowledge exchange. Lu (Reference Loughran and Hamilton2022), for example, examined interdisciplinary cooperation (e.g., geometry, biology, and business) at a Taiwanese university where six content teachers jointly planned and taught an EMI course titled “Science is Everywhere”. Another example illustrated in Xu and Zhang's (Reference Xu and Zhang2022) study depicted the collaboration between an engineering teacher and an English teacher, where they engaged in a process of co-planning, co-teaching, and co-reflection. These two forms of collaboration provided opportunities for both EMI teachers and language teachers to benefit from shared experiences and expertise.

Meanwhile, teacher self-driven practices, in the form of practitioner inquiry, featured as a means for individual EMI teachers to internally synthesize, reflect on, and make changes to their EMI teaching practices. This strand of practitioner inquiry involves a systematic, ethical, and context-sensitive process during which language teachers investigate diversified aspects of teaching and learning based on empirical evidence (Burns, Reference Burns2009; Farrell, Reference Engeström, Engeström and Karkkainen2017). For instance, Cao and Yuan (Reference Burns2020) theorized their experience of conducting action research on an EMI course during which the instructor iteratively clarified misunderstandings and identified improvements for the course.

Based on the identified routes, a continuum can be visualized as shown in Figure 2. Overall, these routes portrayed EMI teacher development as a multi-dimensional process promoted through diverse forms at different levels. Formal training initiatives represented top-down organizational investments as they were typically sponsored and implemented by educational institutions (e.g., university language centers). On the personal end of the spectrum lies a series of self-initiated activities, such as action research and personal reflections. These self-driven practices offered contextualized and customized experiences for EMI teachers to adjust and augment their EMI teaching in response to the situated needs. Yet, an eclectic route – teacher collaboration – can be either implemented by institutions as a teacher training initiative (e.g., Gustafsson, Reference Gustafsson2020) or initiated by individual teachers. For instance, the six content teachers and four language teachers in Lu's (Reference Loughran and Hamilton2022) study voluntarily decided to design an interdisciplinary EMI course after a period of conversations via social media. This route centered on fostering interactive learning communities where EMI teachers collectively planned, designed, implemented, and evaluated authentic teaching scenarios. Generally, the studies demonstrated efforts to support EMI teacher development by accommodating variations in needs, resources, and contexts.

Figure 2. The routes of EMI teacher development

4.2 Route 1: Formal training initiatives

Formal training initiatives accounted for the majority of studies included in the database (n = 21). Table 2 illustrates detailed information on the training initiatives entailed in each study, including the project, the duration, the participants, the objective of the training, and the structure and content of the training initiative. It is important to note that all of these training programs were conducted and implemented in their respective countries. While some programs involved international collaboration through online courses and activities, the teachers did not travel to another country to attend these programs or to participate in these research projects.

As shown in Table 2, the training projects varied considerably in their duration, from five days to five years. Although short-term courses allow for flexible schedules and focused topics, they risk a “hit and run” approach with little room for follow-up feedback, depth of learning, and sustained growth (Borko, Reference Borko2004). Contrarily, multi-year programs may offer tailored-to-fit and ongoing support for EMI teachers to experiment with new approaches and strategies, while also demanding a stronger commitment on the part of EMI teachers. The participants of these training initiatives also showed diversity, ranging from lecturers within a single department to large numbers of EMI instructors across faculties and universities. Most of the participants were EMI instructors only, with one exception – Dafouz (Reference Dafouz2021) – who described a university-level project where multiple levels of staff (e.g., deans, vice deans, heads of departments, administrative staff, and lecturers) participated actively in the EMI curriculum development by sharing their own perspectives and experiences of internationalization. Overall, local or small-scale projects seemed better placed to address specific needs, while their counterparts at the institutional level might catalyze shared reflection and interdisciplinary discussions with impacts on a larger community.

Most projects seemed to share the common goal of raising teachers' awareness of internationalization, meeting the instructional needs of EMI teachers, and better preparing them for EMI teaching. However, there were also more specific objectives identified, such as improving English language proficiency (Volchenkova & Kravtsova, Reference Tuomainen2021), general teaching ability (Park et al., Reference O'Dowd2022), and intercultural and communicative competence (Maíz-Arévalo & Orduna-Nocito, Reference Macaro and Tian2021), and developing language identity (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2019).

Guided by varied objectives, the identified projects encompassed a shared component of expert-led seminars and workshops with topics covering the linguistic, instructional, and digital aspects of EMI teaching. Several studies (e.g., Borsetto & Bier, Reference Borsetto2021; Ismailov, Reference Ismailov2024) reported a blended learning form, combining both online sessions and face-to-face consultations for EMI teacher participants. Meanwhile, most projects offered practical opportunities such as presentations, mini-lessons, and micro-teaching, which allowed participating EMI teachers to apply new knowledge and practice skills acquired in the course in a timely manner, receive constructive feedback in a low-stakes environment, and engage in continuous reflection on their own instructional practices. For instance, in the study conducted by Tsui (Reference Tsui2018), attendees at the end of the program needed to design a lesson with their fellow trainees as their audience. Their micro-teaching would also be evaluated and commented on by a language specialist in terms of the course delivery. Additionally, peer observation and collaboration stood out as prominent activities in some projects (e.g., Morell et al., Reference Morell, Aleson-Carbonell and Escabias-Lloret2022b) that sought to create a sense of community, foster collegial feedback, and build trusting relationships.

In terms of structure and implementation, we further identified several effective practices to offer tailored-to-fit support and sustain long-term development for EMI teachers. For instance, Lauridsen and Lauridsen (Reference Lasagabaster2018) reported the only mandatory project (i.e., requiring all EMI lecturers in the department to participate) in our corpus of 30 articles. Their study examined a collaborative initiative that involved observing authentic classroom teaching of individual EMI teachers. Also notably different from the other projects was the program reported in Tsui's (Reference Tsui2018) study, which required the EMI teachers to conduct a performance presentation three months after their participation. This study not only examined how EMI teachers integrated new ideas into their own classes but also provided suggestions for the improvement of programs. Additionally, four studies (Borsetto & Bier, Reference Borsetto2021; Dafouz, Reference Dafouz2021; Lauridsen & Lauridsen, Reference Lasagabaster2018; Long et al., Reference Lauridsen and Lauridsen2019) specified a sustainable approach to development with continuous evaluation, modification, and evolution of the training programs. Through gathering comments and monitoring teachers' performance, these programs tried to add new content (e.g., a student-centered approach in EMI teaching), and renovate the delivery form (e.g., the shift from blended learning to online-only form). Such measures catered the courses to local and individual requirements and ensured the relevance of the training to the teachers.

Overall, the analysis of Route 1 indicates that formal EMI teacher training demands multi-dimensional and flexible approaches that integrate language, pedagogy, and intercultural dimensions of learning and teaching. During this process, institutions like universities and departments often play a key role in empowering EMI teachers by providing sufficient recognition, support resources, and professional incentives for their continuous development. Meanwhile, institutions also shoulder the key responsibility of facilitating the design and refinement of training initiatives that also double as research-informed practices (e.g., collecting teachers' comments, needs, and evaluations through questionnaires and interviews both pre- and post-training), as these institutions seek to evaluate whether these training initiatives meet the emerging needs of their teaching staff. We next demonstrate the findings of the second research question (i.e., the gains and challenges reported in these formal training activities).

4.2.1 Gains

The studies reported several major types of gains from participating in EMI teacher development programs. One of the common gains was an improvement in language skills and awareness. Many EMI teachers reflected that the programs helped improve their language awareness and ability to teach in English, especially regarding vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation in their disciplinary field. For example, participating teachers reported perceived gains including improved grammatical accuracy and pronunciation of academic words (Margić & Vodopija-Krstanović, Reference Margić and Vodopija-Krstanović2018), increased language proficiency in delivering a lecture or an oral presentation (Tuomainen, Reference Tsui2018), increased lexical knowledge in materials development (Borsetto, Reference Borko2022), adjusted teacher language in response to the specific learning situations (Ismailov, Reference Ismailov2024), and the reinforced role of language facilitators in EMI classrooms (Rubio-Cuenca & Perea-Barberá, Reference Richards and Pun2021).

In addition to the linguistic dimension, the EMI teachers also gained pedagogical knowledge and strategies to be applied in their EMI teaching performance. Participating in carefully designed seminars, in particular, helped teachers facilitate class interactions and student engagement, master pedagogical skills (such as summarizing, emphasizing, and eliciting), design learning activities more naturally, and examine their EMI teaching from alternative perspectives. For instance, EMI teachers appreciated useful suggestions on how to effectively use digital tools in their classrooms (Borsetto & Bier, Reference Borsetto2021), while other teachers demonstrated a diversified use of scaffolding activities such as picture prompts, project work, and pre-teaching vocabulary (Volchenkova & Kravtsova, Reference Tuomainen2021). Notably, Lauridsen and Lauridsen (Reference Lasagabaster2018) found that after the training, their EMI teacher participants incorporated interactive strategies such as summarizing and eliciting questions into their teaching to make the courses more dialogic and student-centered.

Another important gain concerned EMI teachers' psychological changes, such as an increased sense of self-efficacy and confidence. Teachers frequently reported feeling more prepared, empowered, and self-assured in their capability to teach as EMI practitioners after acquiring useful knowledge, practicing teaching in a safe environment, and receiving individualized feedback from those training initiatives. Several studies (e.g., Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2019; Tsui, Reference Tsui2018) narrated cases of EMI teachers who were once hesitant about their language deficiencies and English competence but subsequently regained professional confidence by accepting their own limitations. Teachers also developed empathy toward learners through understanding the challenges involved in EMI learning (Borsetto & Bier, Reference Borsetto2021; Maíz-Arévalo & Orduna-Nocito, Reference Macaro and Tian2021), participating in micro-teaching simulations (Tsui, Reference Tsui2018), and differentiating between learning English and learning content through English (Chen & Peng, Reference Chen and Peng2019). Overall, as the EMI teachers advanced in the training process, they developed a more positive self-image as EMI practitioners and felt more prepared to implement EMI teaching in their future careers.

Other reported gains are equally important, though not as frequently mentioned as the ones stated above. For example, teachers developed a stronger sense of community and received emotional support from bonding with peers and exchanging experiences (e.g., Chen & Peng, Reference Chen and Peng2019; Long et al., Reference Lauridsen and Lauridsen2019). They also appreciated the transferability of the course content that could be applied in other instructional settings (Morell et al., Reference Morell, Aleson-Carbonell and Escabias-Lloret2022b). Some teachers valued the physical environment (e.g., attending courses in a large room overlooking a garden) and the logistic aspects (e.g., a half-day format that did not eat up their entire workday) of the course (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2019).

4.2.2 Challenges

While positive gains can be achieved through formal training, several challenges also emerged from the research. The most prominent one is the difficulty of a differentiated and customized design to accommodate EMI teachers' varied needs in specific contexts. Some studies (e.g., Margić & Vodopija-Krstanović, Reference Margić and Vodopija-Krstanović2018; Tuomainen, Reference Tsui2018) pointed out that mixed-level classes, without tailoring to different English proficiency levels, made it difficult for all teachers to learn optimally and even created discomfort among participants. Similar contradictory needs stemming from individual dispositions were frequently observed. For example, some clinical instructors preferred hands-on knowledge that could be directly applied in their teaching practices, while other lecturers with doctorates were used to engaging in more broad discussions on pedagogical considerations and educational philosophies (Tuomainen, Reference Tsui2018). Of the three EMI instructors interviewed in Long et al.'s (Reference Lauridsen and Lauridsen2019) research, one participant suggested adding discipline-specific meetings with a focus on the specialized discourses, whereas the other two participants expressed the need for concrete language development opportunities on a regular basis. Similarly, some EMI teachers pointed out the inefficiency of micro-teaching activities as they were drastically different from authentic classroom settings (Chen & Peng, Reference Chen and Peng2019), and expressed the need for training that focused on pronunciation and prosody instead of general topics of EMI teaching (Morell et al., Reference Morell, Aleson-Carbonell and Escabias-Lloret2022b). This suggests that a one-size-fits-all approach to EMI teacher development may not be adequate and effective.

Similar challenges were witnessed in the design and implementation of the training initiatives. The lack of institutional commitment and support constrained program effectiveness and sustainability. Dafouz (Reference Dafouz2021), for example, stated how unpredictable management changes could interrupt the strategic planning of professional development programs, which underscores the importance of embedding training initiatives within wider institutional strategies.

As for teachers, no obvious change was found in some teachers' pedagogical practices after the training. For example, they were still unaware of the importance of using meta-discourse devices in teaching (Carrió-Pastor, Reference Cao and Yuan2022) or the role of non-verbal communicative acts (Maíz-Arévalo & Orduna-Nocito, Reference Macaro and Tian2021). This issue can be attributed to teachers' low motivation and reluctance to change due to deep-rooted beliefs formed over prolonged practice. For instance, Dafouz (Reference Dafouz2021) observed reluctance to change their pedagogy because some EMI teachers in Spain believed the role of Spanish might be threatened. Such affective barriers call for culturally sensitive design and psychological support. Even for those projects that reported positive changes, it is unknown whether such effects would be sustained over teachers' long-term practice. Crucially, Ismailov (Reference Ismailov2024) cautioned that the training may not easily be translated into a seamless application in the classroom, despite the creation of a well-organized design of the program. Therefore, a longer period of classes and follow-up modules to internalize the materials need to be provided, as suggested in Margić and Vodopija-Krstanović's (Reference Margić and Vodopija-Krstanović2018) study in order to generate multiple touchpoints for incremental change to take place.

The risk of increased negative emotions posed another major drawback. In Maíz-Arévalo and Orduna-Nocito (Reference Macaro and Tian2021), the percentage of teachers who admitted fear and anxiety in intercultural exchanges rose from 5% to 72% after the training; the jump in fear and anxiety could potentially be attributed to EMI teachers' increased awareness of the complexities of classroom teaching. Other studies also reported that the program led to teachers' self-doubt about their ability to implement EMI teaching (Margić & Vodopija-Krstanović, Reference Margić and Vodopija-Krstanović2018), as illustrated by the reservation of a weaker attendee who lamented “how much [s/he lacked] to teach in English” (p. 36). Similarly, some teachers reflected that the training was limited in usefulness, since it pushed them to be compared with more capable peers, thereby leading to their reduced confidence and motivation (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2019).

To summarize, EMI training programs, while helping alleviate pressing needs, might fall short in terms of a holistic, contextualized, and systematic design, thus undermining the transformative potential of formal training initiatives. Furthermore, the training seemed to be stuck on knowledge inculcation without heightened attention to profound issues such as EMI teachers' identity construction and emotional well-being. For institutions where no such teacher development programs exist yet, the potential benefits for both EMI teachers and students should be communicated to the institutional administration to initiate the first step toward pedagogical enhancement and professional development. Meanwhile, for institutions that already have similar teacher development projects, future enhancements could consider a curriculum designed after a needs analysis of the target EMI teachers, prolonged support networks, embedded assessment strategies, as well as a widened lens to incorporate socio-emotional elements into EMI teachers' professional practice and growth. Despite the challenges (e.g., a lack of resources and difficulties in coordination) of a tailored and customized curriculum for EMI teachers, this should be a direction that the collaborative efforts of relevant stakeholders should aspire toward.

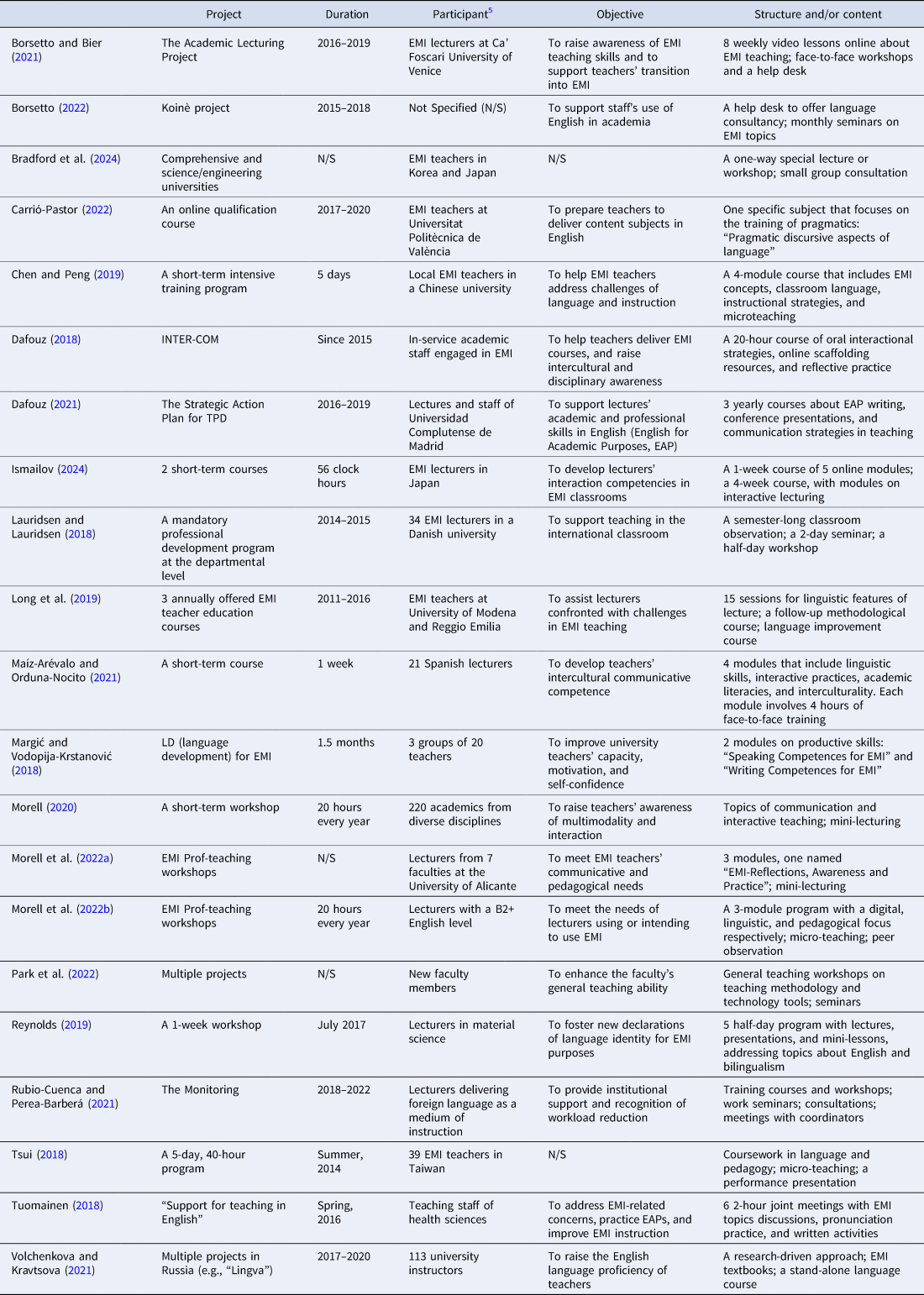

4.3 Route 2: Teacher collaboration

In this section, we explore the second identified route to EMI teacher development – teacher collaboration (n = 7). Table 3 details the project, duration, participants, objective, and procedure of EMI teacher collaboration. In contrast with formal training initiatives, EMI teacher collaboration seems to be undertaken through relatively longer-term partnerships (e.g., over the duration of one semester). The participant profile suggests that collaboration often occurred between EMI teachers and language specialists who sought to promote expertise exchange and mutual learning. Collaboration, however, is a far more complex endeavor than often envisaged. This reality is reflected in the work conducted by a collaborative team in Gustafsson's (Reference Gustafsson2020) study. Importantly, collaboration often involves cooperative efforts from a slew of key educational partners, including EMI teachers, applied linguists, and educational specialists in the content area (i.e., medical education). Such productive cooperation is rarely seen in other EMI teacher collaboration studies, however.

Table 3. Teacher collaboration for EMI teacher development

With a shared objective of empowering EMI teachers to teach content subjects more effectively through an additional language, these collaborative initiatives were designed to support EMI teachers in preparing lessons, applying theories in practice, or developing linguistically-informed pedagogy. During this process, although language teachers/specialists appeared to be more “authoritative” in giving linguistic and pedagogical guidance, they were constantly assigned an inferior role as “a supporter”, which was detrimental to constructing a mutually beneficial and equal relationship. This situation was ameliorated in Macaro and Tian's (Reference Macaro and Tian2023) study, in which a model of equal-status collaborative research was proposed to benefit both sides.

The procedure of collaboration can be divided into two broad categories. Some studies mentioned a deep-involvement approach including co-planning, co-developing, and co-teaching of courses between EMI teachers and language specialists (e.g., Lu, Reference Loughran and Hamilton2022), while others reported an assistance approach where language teachers observed, analyzed, and gave feedback to the courses delivered by EMI teachers (e.g., Ploettner, Reference Phillipson and Skutnabb-Kangas2019a). The former approach may allow for more opportunities to discuss interactively, deal with instructional challenges collaboratively, and apply expert guidance in authentic settings.

To summarize, these studies present EMI teacher collaboration as a promising yet eclectic avenue for continuing professional development. It can be either implemented by institutions as a teacher training initiative (e.g., Gustafsson, Reference Gustafsson2020) or proposed by individual teachers based on their own needs and situations. Therefore, conceptualizing EMI teacher development as a collaborative process may nurture an understanding of effective support for the growing population of EMI practitioners, and help them navigate linguistic and disciplinary frontiers simultaneously. We highlight both gains and challenges reported in the identified studies of Route 2 – teacher collaboration – next.

4.3.1 Gains

The first gain that emerged across multiple studies was the development of self-awareness of linguistic issues among EMI teachers through collaboration, which prompted teachers to reflect on their grammatical errors (Macaro & Tian, Reference Macaro and Tian2023), balance the use of first and second languages in teaching (Xu & Zhang, Reference Xu and Zhang2022), and modify their instructional language use in practice. Gustafsson (Reference Gustafsson2020) exemplified how mapping linguistic functions helped EMI medical teachers employ specific strategies for different lecture types. For example, through awareness-raising discussions, EMI teachers were able to achieve a clearer communicative purpose by replacing formulations that might lead to misunderstandings (e.g., “What do you have in your head?”). Similarly, Lu (Reference Loughran and Hamilton2022) also illustrated how collaboration made teachers conscious of adjusting instructional language for learner comprehension. To define the structural elements “pier” and “abutment”, the EMI instructor preemptively provided visual and linguistic scaffolding to clarify the unfamiliar lexicon, which was part of the language teaching strategies provided by the language teachers. This responsive approach (i.e., integrating a pictorial representation with simplified definitions) illustrated the EMI teacher's cognizance of leveraging multiple modalities to translate subject-specific linguistic features into more accessible forms through working closely with language specialists, thereby facilitating bridge-building between new disciplinary concepts and students' prior knowledge base.

The collaboration also broadened EMI teachers' pedagogical repertoire by moving beyond sole content delivery (Ploettner, Reference Ploettner2019b). Lu (Reference Loughran and Hamilton2022) reported changes in content teachers in terms of more student-centered lesson planning, more creative integration of language and content, and more new perspectives in employing teaching strategies through their collaborative engagements. For instance, by collaboratively designing cross-disciplinary lessons utilizing real-world narratives and embedded language exercises, the EMI teachers transformed static content delivery into active language-rich engagement capitalizing on students' diverse experiences. Xu and Zhang (Reference Xu and Zhang2022) also noted EMI teachers' changes from insensitivity to students' learning difficulties in EMI to increased provision of language scaffolding (e.g., made deliberate efforts to organize classroom activities for students to practice oral and written skills), after several months of co-planning and co-teaching with an English teacher. During this collaborative process, the EMI teacher gradually accepted his responsibility of attending to students' language issues and reconstructed his identity as a language facilitator (but not a language teacher).

Collaboration seemed to foster community and emotional support. Working within a team structure cultivated a constructive mentoring environment where the teachers could elevate one another's satisfaction and guidance through peer coaching on teaching methods, language-related activities, and communicative strategies (Lu, Reference Loughran and Hamilton2022). It is frequently reported that collaboration fostered a supportive peer community that boosted self-efficacy and positive attitudes regarding EMI instruction. For instance, teachers in Gustafsson's (Reference Gustafsson2020) study recalled how briefing sessions and on-demand support aided EMI medical teachers in building a supportive community of practice where they could address shared pedagogical challenges and seek suggestions for promoting intercultural communication.

4.3.2 Challenges

While collaboration yields promising benefits, its success may vary given individual teacher dispositions. For example, Macaro and Tian (Reference Macaro and Tian2023) found one teacher less receptive than another due to individual dispositions, exemplified by a low engagement in the collaborative process, a teacher-dominant lecturing style, and the persistent belief that language teaching fell outside her perceived responsibilities. This suggests the need to differentiate support with respect to EMI teachers' individual dispositions to optimize impact for all practitioners transitioning to become competent EMI teachers. A second constraint concerns the unequal distribution of roles and authority in collaborative partnerships. Ploettner (Reference Phillipson and Skutnabb-Kangas2019a) observed the language specialist claiming more epistemic authority over the collaborative process by controlling the interactive discourse and the interpretation of the official documents, therefore undermining intended interdisciplinarity. Contextual demands and administrative issues comprised a third challenge. Heavy teaching loads, busy schedules, and lack of time were regularly cited as preventing collaboration (Alhassan et al., Reference Aguilar-Pérez and Khan2022). EMI teachers in Alhassan et al.'s (Reference Aguilar-Pérez and Khan2022) study attributed a lack of regular communication to the absence of administrative organization, and suggested a more systematic way of collaboration with external guidance.

To conclude, while collaboration yields professional gains in both cognitive and social domains, its implementation requires thoughtful consideration of individual variables and contextual constraints to maximize its effectiveness. For instance, disparities in expertise, unequal status, and unevenly distributed responsibilities have the potential to skew collaboration dynamics. Therefore, both academic and administrative support remain vital for fruitful EMI teacher partnerships. Meanwhile, the low number of participating teachers involved in collaboration is yet another limitation. In more than half of the reviewed studies above, only one or two EMI teachers engaged in collaborative teaching. Therefore, relevant stakeholders ought to invest in and employ various strategies and incentives to attract and involve more teachers in future collaborative efforts, where a larger proportion of individuals can benefit from this form of teacher development. Future collaborative models could also employ more flexible, dialogic approaches sensitive to power asymmetries and educational realities, in order to maximize the potential of EMI teacher collaboration.

4.4 Route 3: Self-driven practices

Compared with formal training initiatives and teacher collaboration, EMI teachers' self-driven practices seemed to be overlooked, with only two practitioner inquiries (Cao & Yuan, Reference Burns2020; Qin et al., Reference Ploettner2023) identified in our review process. Through critically examining taken-for-granted practices, practitioner research, in diverse forms such as action research and self-studies, aims to empower educational practitioners to take control of changes in their own settings and address authentic problems within the local context (Burns, Reference Burns2009). Such a paradigm has the potential to facilitate critical reflection on teachers' situated beliefs and practices, enhance their agency, increase the authenticity and ecological validity of research, and catalyze potential transformations (Farrell, Reference Engeström, Engeström and Karkkainen2017). Despite the potential benefits, practitioner inquiry may require a substantial time commitment for data collection, analysis, and knowledge sharing on top of teachers' daily work responsibilities, while institutional or collegial support from others might often be absent (Loughran & Hamilton, Reference Long, Poppi and Radighieri2016). These might explain the scarcity of research in the EMI field.

Cao and Yuan (Reference Burns2020) reported an action research project conducted by a teacher who specializes in international business and teaches an EMI course (Principles and Practices of Marketing) at a Chinese university. Presented with significant challenges in the students' limited English proficiency, restricted classroom participation, and hindered understanding of the disciplinary content, the authors adopted action research to examine and enhance teaching practice over one semester. The teacher promoted student learning motivation and participation through strategies including permitting code-switching and incorporating local examples, and later emphasized integrating content and language learning for professional purposes in business.

The authors presented major gains of such EMI action research experience, including heightened language awareness, improved pedagogical practices, and teachers' ongoing professional development (Cao & Yuan, Reference Burns2020). First, the teacher demonstrated heightened metalinguistic awareness and an understanding of “language as a crucial means to understand, learn and conduct business” (p. 242), which allowed her to make pedagogical decisions catering to both content and language issues simultaneously. Second, through action research, the teacher crafted nuanced strategies to respond to diverse learner profiles. For example, the teacher drew on bilingual videos to explicate a business concept and adopted a more flexible language policy in EMI classrooms in order to address students' cognitive and emotional needs. Third, the experience of action research also strengthened the teacher's belief that teaching and research are not mutually exclusive; instead, they can “go hand in hand” (p. 242) through ongoing reflections and support from colleagues.

Another practitioner inquiry conducted by Qin et al. (Reference Ploettner2023) employed autoethnographic narratives to explore contradictions embedded in EMI teaching in a Chinese university. Through storying and re-storying (Craig, Reference Chen and Peng2007), their autoethnography afforded a nuanced analysis of the seven contradictions involved in EMI classrooms (e.g., teacher-centered versus student-centered educational beliefs, direct instruction versus self-regulated learning, individual learning versus group-based work, etc.). During this process, the instructor of an EMI teacher education course engaged in iterative narration and revisitation of multiple facets of teaching, ranging from pedagogical specifics (e.g., classroom teaching activities) to broader educational philosophy (e.g., a democratic approach). Such analytical moves supported the teacher's comprehension of EMI as situated within intersecting contextual, interactional, and ideological spheres. While generating implications for reconciling the problematic spaces associated with implementing EMI, the reflection process also helped to achieve a nuanced understanding of the dynamics and complexities involved in an EMI course and provided opportunities for course refinement to meet the needs of students.

Taken together, the two studies (Cao & Yuan, Reference Burns2020; Qin et al., Reference Ploettner2023) demonstrate how EMI teachers can gain pedagogical insights from actively reflecting on and researching their practices. The process of problem identification, self-reflection, and pedagogical adaptation experienced by EMI teachers during their self-initiated practices may have a potential transforming and empowering impact on teachers' pedagogical beliefs and self-positionings (Cao & Yuan, Reference Burns2020; Qin et al., Reference Ploettner2023). Yet, challenges or drawbacks were largely omitted in the selected two practitioner inquiries. First, longer-term impact evaluations are needed to fully discover the effectiveness in an extended timeframe. For example, although teachers' language awareness is important for EMI teaching, it does not necessarily develop into effective instruction. While both studies report growth, the longer-term impact beyond a single semester or course remains unclear. Therefore, sustained reflection over time with systematic assessments could more robustly demonstrate pedagogical as well as professional outcomes. Second, critiques note solitary reflection has limitations, as outside perspectives can help produce more nuanced and systematic insights (Burns, Reference Burns2009). Cao and Yuan (Reference Burns2020) acknowledged this drawback, highlighting the value of reflective discussions with language specialists based on concrete classroom problems or scenarios.

4.5 Methodological considerations

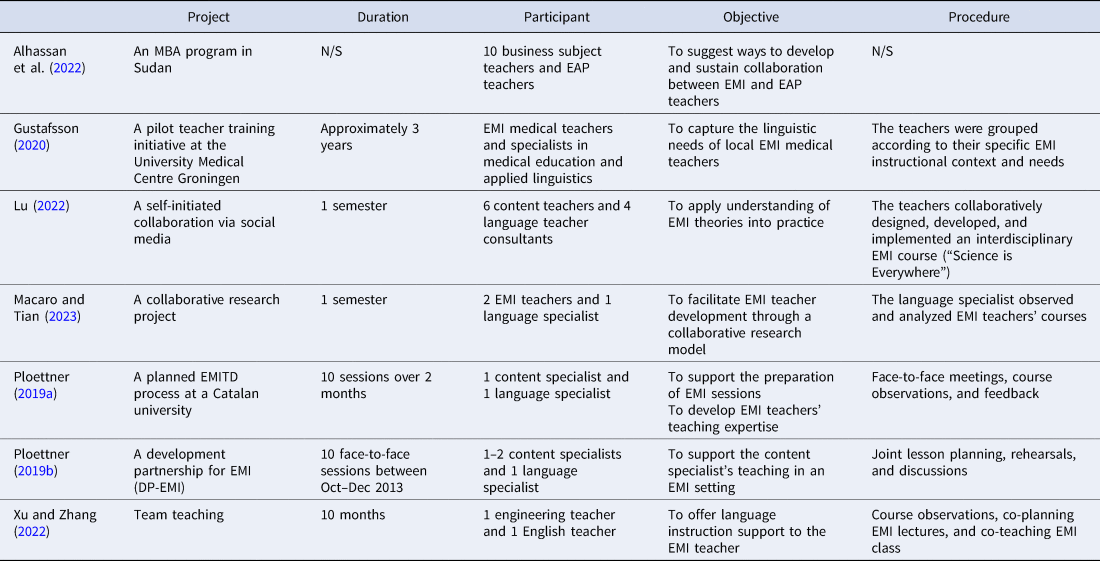

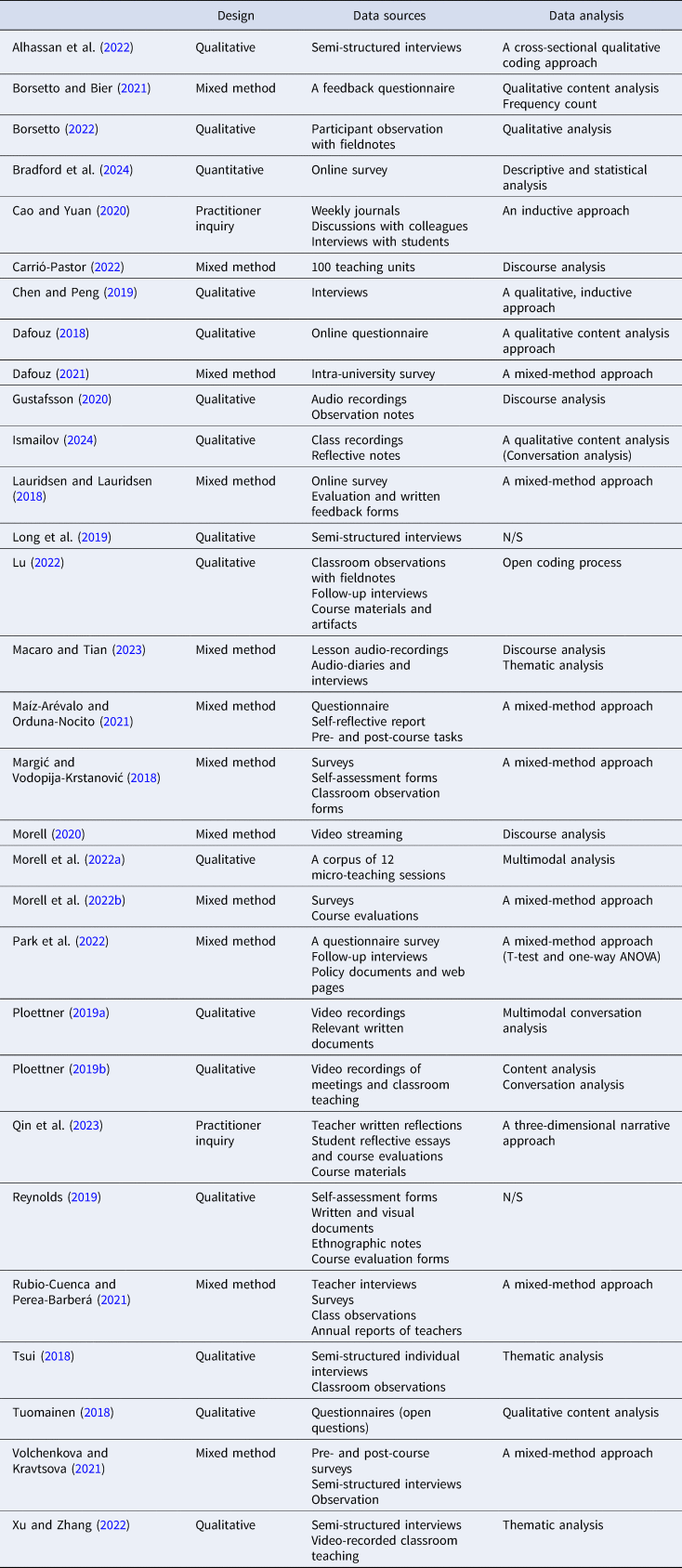

In order to address the third research question, we analyzed the methodology sections of the selected papers with attention to the research design, the sources of data, and the methods for data analysis. The results are summarized in Table 4. The review process yielded four major types of research design.

Table 4. Methodological information of the selected studies

Overall, half of the studies (n = 15; 50%) adopted a qualitative, interpretative design, with only one study following a purely quantitative approach. Additionally, one study engaged in practitioner inquiry in the form of action research (Cao & Yuan, Reference Burns2020), and another was an autoethnographic narrative (Qin et al., Reference Ploettner2023). There was also a group of studies (n = 12; 40%) that employed a mixed-method design incorporating both qualitative and quantitative elements. For example, in Rubio-Cuenca and Perea-Barberá's (Reference Richards and Pun2021) study, the teachers were first interviewed by language assistants with respect to their general attitudes, needs, and experiences with the training programs. Then, other types of data, such as surveys administered to EMI students, were used to gain a quantitative understanding of the overall effectiveness of the training programs. The mixture of both qualitative and quantitative data may generate a more comprehensive picture of both the process and outcomes of EMI teachers' learning in the development initiatives.

As shown in Table 4, most of the selected studies employed either qualitative or mixed-method design to investigate cases of EMI teacher development within one specific institution or several institutions (e.g., departments or universities). Three studies (Ismailov, Reference Ismailov2024; Qin et al., Reference Ploettner2023; Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2019) employed an ethnographic design, where the researchers immersed themselves in the research site for an extended period to gain first-hand data on either authentic classroom teaching or training programs. Therefore, a rich and thick description of not only the contextual details but also the participants' authentic experiences should be observed in order to synthesize the affordances and constraints of the teacher development activities. There are also two corpus-based studies (Carrió-Pastor, Reference Cao and Yuan2022; Morell et al., Reference Morell, Aleson-Carbonell and Escabias-Lloret2022a) that analyzed a relatively large number of teachers' (micro-)teaching episodes. Since the two studies focused on the discursive features of EMI teachers' instruction, the corpus approach can be useful to give a microanalysis of the linguistic details and interactive behaviors at the discourse level. Of particular interest is a longitudinal study conducted by Borsetto (Reference Borko2022) in which the researcher (an insider) collected data through participant observation over seven months. Such a longitudinal perspective, therefore, has the potential to illuminate unanticipated relationships or patterns by tracking the teachers' experiences over time.

4.5.1 Data sources

Regarding data sources, the most utilized were surveys, interviews, observations, and instructional documents. First, surveys with both closed and open-ended questions were conducted in multiple studies to gather insights from teachers participating in training initiatives, addressing topics such as perceived needs, experiences with professional development opportunities, and assessments of particular training courses and impacts (e.g., Dafouz, Reference Dafouz2021; Park et al., Reference O'Dowd2022). In three studies (Maíz-Arévalo & Orduna-Nocito, Reference Macaro and Tian2021; Tuomainen, Reference Tsui2018; Volchenkova & Kravtsova, Reference Tuomainen2021), questionnaires were administered before and after training interventions to investigate both teachers' perceived needs and evaluations of the teacher development activities. In general, these surveys can efficiently gather data from a large number of participants involved in EMI teacher development activities, thereby allowing researchers to describe patterns, enable comparisons, and support generalizability. However, they can also risk superficiality by providing a surface-level broad understanding and reducing contextual richness and complexity (Burns, Reference Burns2009).

Second, semi-structured interviews were another prominent source used alone or in combination with other tools, which can potentially generate profound and genuine insights into nuanced personal experiences and perceptions in EMI teacher development. Interview protocols were designed to probe into EMI teachers' experiences of teaching, perceptions of training activities, and reflections (e.g., Alhassan et al., Reference Aguilar-Pérez and Khan2022; Tsui, Reference Tsui2018). Two studies (Macaro & Tian, Reference Macaro and Tian2023; Xu & Zhang, Reference Xu and Zhang2022) conducted initial interviews to gather teachers' baseline understandings, followed teacher collaboration over time with further interviews to gain longitudinal insights, and examined reflections at the end of the team-teaching process. In particular, Alhassan et al. (Reference Aguilar-Pérez and Khan2022) mentioned using prompt cards (e.g., examples of different levels of teacher collaboration) during interviews to elicit more nuanced, focused, and in-depth responses from EMI teachers. Overall, while interviews can facilitate open-ended, in-depth exploration of key issues on a more manageable scale, self-reported data can face critiques of reliability, especially when compared with observable behaviors.

Third, observations undertaken by a third-party individual (e.g., a researcher or expert outside the teacher development programs to assess effectiveness) proved vital in the selected studies. Frequently, such observations were conducted by directly examining how EMI teachers' pedagogical skills and language use, after training or collaboration, were applied in authentic or artificial (e.g., micro-teaching) teaching contexts. Some studies returned to classroom episodes multiple times to trace interactive patterns (e.g., Ismailov, Reference Ismailov2024), while others qualitatively reported rich descriptive snapshots gleaned from observations (e.g., Morell, Reference Metzger2020). These observations allow researchers to gather different dimensions of direct data, such as observable behaviors, pedagogical moves, teacher–student interactions, and non-verbal communications that occurred in classroom settings. More importantly, they may help to capture details that may not be evident through other data collection tools (e.g., interviews), and provide a richer perspective than self-reported data alone.

Overall, the studies drew from a variety of data sources, providing well-rounded lenses for illuminating the multifaceted experiences and impacts associated with EMI teacher development opportunities. In addition to surveys, interviews, and observations, these studies also resorted to artifacts such as course materials, written assignments, annual reports, evaluation forms, and policy documents, in order to complement understandings generated from other sources. Such a triangulation of multiple sources achieved a comprehensive outlook of the outcomes, processes, and stakeholders' views in EMI teacher development activities. However, not all studies incorporated a robust design. Notable gaps included a lack of classroom observational components in survey-only studies and an over-reliance on self-reports. Meanwhile, some studies also failed to sufficiently validate findings in different phases (e.g., employing both pre- and post-course evaluations), sacrificing potential insights regarding EMI teachers' long-term development. Importantly, student perspectives tended to be underrepresented despite being directly affected by EMI teachers' instructional practices, with only three exceptions (Cao & Yuan, Reference Burns2020; Qin et al., Reference Ploettner2023; Rubio-Cuenca & Perea-Barberá, Reference Richards and Pun2021). Therefore, future research can enhance reliability, trustworthiness, and complementarity by verifying understandings across divergent data types, stakeholders, and stages of teacher development activities.

4.5.2 Data interpretation

The majority of qualitative studies engaged in inductive coding processes to derive patterns and themes directly from their data. Across interview-based qualitative studies, guided dimensions and aspects for coding, based on focal research aims, encompassed perceived challenges (e.g., Long et al., Reference Lauridsen and Lauridsen2019), shifts in self-efficacy beliefs (e.g., Chen & Peng, Reference Chen and Peng2019), gains in pedagogical strategies (e.g., Lu, Reference Loughran and Hamilton2022), awareness of learners (e.g., Xu & Zhang, Reference Xu and Zhang2022), and assessments of training initiatives (e.g., Tsui, Reference Tsui2018). Steps commonly involved iterative readings of interview transcripts and observation notes to apply open codes capturing emerging concepts, consolidate codes into overarching categories, and iteratively refine categories through comparative analysis across the full dataset (e.g., Xu & Zhang, Reference Xu and Zhang2022). Such an interpretive paradigm allows for a nuanced understanding of EMI teachers' lived experiences, perceptions, and decision-making processes during their development (De Costa et al., Reference De Costa, Green-Eneix and Li2019; Dörnyei, Reference Doiz and Lasagabaster2007). Meanwhile, several studies applied quantitative analysis to survey Likert items, extracting frequency counts and mean values to statistically gauge levels of agreement (e.g., Bradford et al., Reference Bradford, Park and Brown2024), or to conduct ANOVA analysis of variance to compare perceptions between subgroups (e.g., Park et al., Reference O'Dowd2022). There are also studies (n = 8; 26.67%) employing a mixed-method approach to data analysis, which can balance statistical generalizability with rich narrative understandings.

Generally, the qualitative analysis methods might involve a higher level of subjectivity in coding and theme identification, and thus need triangulated interpretations (Dörnyei, Reference Doiz and Lasagabaster2007). Quantitative analysis measures, on the other hand, rely too much on pre-determined assumptions and hypotheses, while failing to capture the richness of situated meaning in EMI teachers' daily practices and continuing development. More triangulation of different analysis techniques is desired for a comprehensive picture of EMI teacher development. Also, employing discourse analysis in examining teacher collaboration may yield a nuanced understanding of the power dynamics and roles division during the collaborative process.

In conclusion, well-planned pairing and cross-validation between divergent yet complementary approaches (e.g., qualitative and quantitative methods) hold promise for a more comprehensive and situated understanding of the complex EMI teacher development phenomenon. Consistent use of systematic data interpretation methods supports the production of contextualized understandings, and yields evidence-based conclusions regarding effective support mechanisms for EMI teacher development. Moving forward, enriched triangulation, which entails systematically merging surveys, interviews, observations, documents and potentially additional methods like stimulated recalls, could generate more systematic, trustworthy results. Incorporating the voices of EMI students and administrators and following the teachers for an extended period can not only broaden contextual understandings but also provide concrete evidence of the effectiveness and trajectories of EMI teacher development activities. Given the paucity of practitioner research in this field, we suggest that EMI teachers utilize action research and self-study to foster a contextualized understanding of practices and a commitment to teaching innovations and self-transformation. For instance, they can be the “investigator” of their own contexts (Burns, Reference Burns2009, p. 2) by taking cyclical rounds of pedagogical actions to ameliorate an identified problem in their EMI teaching. Alternatively, they can employ an autoethnographic or narrative approach to investigate their own beliefs, practices, philosophies, and reflections in the context of EMI education.

5. Discussion

The review has identified three different routes to EMI teacher development (i.e., formal training initiatives, teacher collaboration, and self-driven practices). In analyzing each route, we have demonstrated the details of these teacher development opportunities (e.g., duration, participants, objectives, structure, and procedure), followed by a critical review of their reported gains and challenges. Equal attention has also been given to their methodological considerations in terms of design, data sources, and methods of analysis. Our analysis shows that EMI teacher development can be characterized as a hybrid, contested, and transformative process in situated contexts.

EMI teacher development is a hybrid process shaped by the joint forces of communities and stakeholders in higher education. As illustrated in Figure 2, a rich variety of routes was provided for EMI teachers to engage in continuous learning. The continuum incorporates different levels of educational domains and stakeholders involved. Some formal training projects were guided by university-level initiatives. For instance, Rubio-Cuenca and Perea-Barberá (Reference Richards and Pun2021) described how the EMI in-service training programs were paralleled by a university-level strategic plan (i.e., Program for the Support of Foreign Language Lecturing at the University of Cádiz), with the aim of offering institutional recognition and workload reduction to EMI teachers. Other projects (e.g., Borsetto, Reference Borko2022; Chen & Peng, Reference Chen and Peng2019), however, were launched at the department level within a university for academic staff to cater to local needs (e.g., to improve EMI lecturers' English proficiency).

Meanwhile, the hybrid nature of EMI teacher development also arises from a high level of boundary-crossing between diverse physical and conceptual spheres in the higher education context. According to the review, EMI teacher development initiatives need to incorporate various facets of EMI teaching. This requires not only a heightened focus on the pedagogical dimensions of EMI but also an inclusion of broader educational topics, such as bilingualism and national/local language policies (e.g., Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2019), technology and multimodal communication (e.g., Morell et al., Reference Morell, Aleson-Carbonell and Escabias-Lloret2022b), and internationalization and intercultural issues (e.g., Borsetto & Bier, Reference Borsetto2021). In particular, the informal routes (teacher collaboration and self-initiated practices) entail the elements of seeking professional advice from the linguistic domain, or augmenting discipline-specific practices mediated by the English language. In other words, given the multidisciplinary nature of their professional practice, EMI teachers often need to cross diverse domains (more often than not their disciplinary content group and English language group) in order to discover new instructional visions and resources, broaden and refresh their beliefs about teaching, and develop new types of social relationships (in the form of teacher collaboration). For example, most selected studies reported that EMI teachers, after participating in the teacher development activities, developed a heightened awareness of language, and subsequently modified their teaching by providing additional language scaffolding (e.g., Gustafsson, Reference Gustafsson2020; Macaro & Tian, Reference Macaro and Tian2023). In this way, EMI teachers seem to successfully integrate “ingredients from different contexts to achieve hybrid situations” (Engeström et al., Reference Dörnyei1995, p. 319).