Introduction

Oxidation zones and mine wastes are critical zones of ore deposits, either in situ or after human-driven re-deposition, respectively. The critical zone is a near-surface environment, a thin layer connecting atmosphere and geosphere (Küsel et al., Reference Küsel, Totsche, Trumbore, Lehmann, Steinhäuser and Herrmann2016). Within the critical zone, metal cycling, mineral precipitation and dissolution may be driven by inorganic processes or by organisms (Chorover et al., Reference Chorover, Kretzschmar, Garcia-Pichel and Sparks2007; Gadd, Reference Gadd2012) and can be traced by various mineralogical and geochemical methods (Blanckenburg and Schuessler, Reference Blanckenburg and Schuessler2014; Li et al., Reference Li, Maher, Navarre-Sitchler, Druhan, Meile, Lawrence, Moore, Perdrial, Sullivan, Thompson, Jin, Bolton, Brantley, Dietrich, Mayer, Steefel, Valocchi, Zachara, Kocar, Mcintosh, Bao, Tutolo, Beisman, Kumar and Sonnenthal2017). The oxidation zones and mine wastes are dynamic geochemical reactors where the primary minerals transform in contact with water, oxygen, CO2, and biological activity to a suite of secondary phases (Williams, Reference Williams1990; Lottermoser, Reference Lottermoser2010). Oxidation zones deviate much from natural, pristine and uncontaminated critical zones but they provide valuable information about metal cycling in the interface between the atmosphere and bedrock.

In dumps, tailings and metallurgical waste, oxidation and decomposition is relatively fast and converges, in terms of mineralogy and geochemistry, with the natural oxidation zones. Many secondary minerals are metastable and convert at variable rates to the stable phases. Why and how do these metastable minerals form in the first place? Why do we find in some systems (for example, copper arsenates) so many metastable phases? The goal of this work is to contemplate on the origin of many metastable minerals in the oxidation zones and mine wastes. They serve as superb examples of the processes in the near-surface environments. Because of the elevated concentration of many metals and metalloids, they are much more amenable to many laboratory techniques with higher detection limits, including various types of microscopy as visualisation methods, for example transmission electron microscopy (e.g. Petrunic et al., Reference Petrunic, Al, Weaver and Hall2009).

Metastability and structural complexity of minerals

The relative stability or metastability of minerals seems to be associated with their structural complexity (Krivovichev, Reference Krivovichev2013), although a quantitative link is missing. It seems that more stable polymorphs are those which are more structurally complex. For example, the Gibbs free energy difference between the polymorphs parabutlerite and butlerite [Fe(SO4)(OH)(H2O)2] is 0.65 ± 0.19 kJ⋅mol–1, with parabutlerite marginally more stable (Majzlan et al., Reference Majzlan, Dachs, Benisek, Plášil and Sejkora2018a). Parabutlerite has, indeed, higher structural complexity of 33 bits/formula unit, compared to 25 bits/formula unit for butlerite. An almost linear relationship between stability and structural complexity was observed among Cu2(OH)3Cl polymorphs botallackite, atacamite and clinoatacamite (Krivovichev et al., Reference Krivovichev, Hawthorne and Williams2017).

The relationship among chemically related phases is much more difficult to express; for example, the equilibrium between butlerite and amarantite [Fe(SO4)(OH)(H2O)3] depends not only on the crystal structures of the participating phases but also on water activity or water vapour fugacity. Available data suggest that even in such cases, more complex phases may have greater stability (see Majzlan et al., Reference Majzlan, Dachs, Benisek, Plášil and Sejkora2018a, their fig. 12) but this is not to say that exceedingly complex structures must be very stable.

The Ostwald's step rule assumes that the first phase to form is the one that requires the smallest activation energy, even if it is metastable. The rule is re-iterated by theoretical treatment of van Santen (Reference van Santen1984) or ten Wolde and Frenkel (Reference ten Wolde and Frenkel1999). It can be rephrased in terms of surface-energy arguments (Navrotsky, Reference Navrotsky2004), that the activation energy is proportional to the surface energy of the crystallising phase. There is a tendency, but no rule, that structurally more complex phases are more stable. If such relationships hold then the Ostwald's step rule may be expressed also in terms of a system initially precipitating simple structures that can be easily assembled from aqueous solutions, nanoparticles, gels and clusters. The simple structures are then converted to more complex and more stable ones. The structural similarity of the precursor and the forming phase is a kinetic factor that favours the crystallisation of the new phase. Metastable phases are promoted when the precursor and the new phase possess some structural similarities. This concept has been used for a long time in synthesis protocols within the so-called chimie douce (Figlarz, Reference Figlarz1988; Livage, Reference Livage2001).

Stabilisation of minerals by their surface energy

Even though not commonly considered, surface energy plays an important role in shifting the equilibria in near-surface systems with abundant high surface-area phases. Anderson (Reference Anderson2005) stated that the thermodynamic equations only rarely need to consider other types of work than the mechanical work –PΔV. Yet, for finely divided and nanosised phases, the surface-work term γΔA needs to be included and considered.

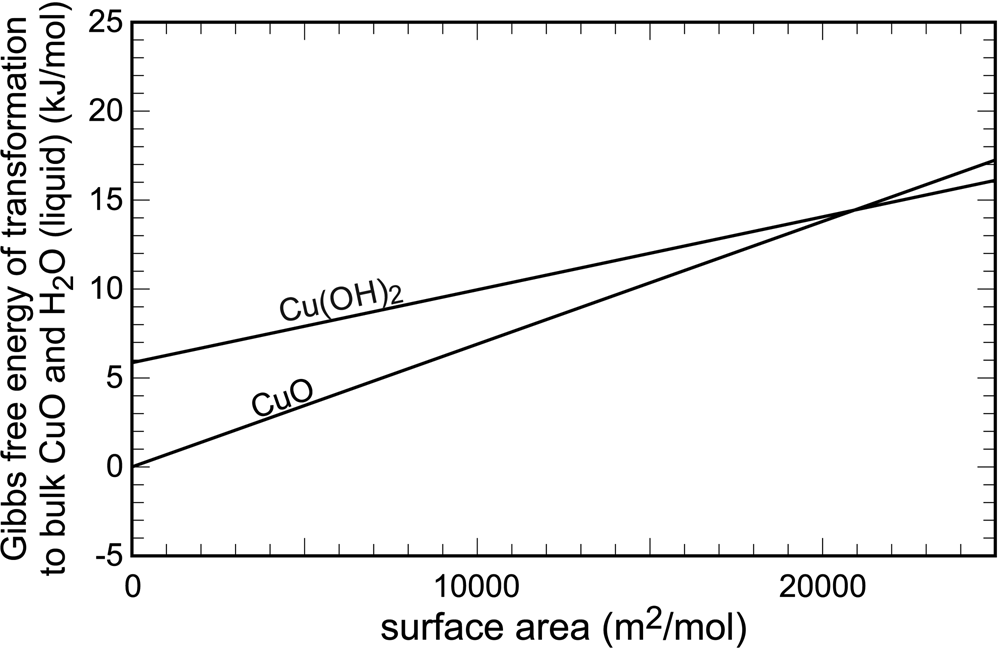

The surface (or interface) energies were quantified early, for example by Enüstün and Turkevich (Reference Enüstün and Turkevich1959) or Schindler et al. (Reference Schindler, Althaus, Hofer and Minder1965), among others. The data from Schindler et al. (Reference Schindler, Althaus, Hofer and Minder1965) are displayed graphically in Fig. 1. In bulk crystals, tenorite (CuO) and water are 6 kJ⋅mol–1 more stable than spertiniite [Cu(OH)2]. The slopes of the two lines in Fig. 1 are equal to the surface energies of the two cupric phases. They are a graphical representation of the increase of Gibbs free energy upon an increase of surface area. The point where these curves intersect is the free energy crossover. Beyond this point, the phase that was metastable in large, bulk crystals, becomes stable in the finely divided form. Hence, for finely divided cupric solids, spertiniite will be preferred over tenorite.

Fig. 1. Variations of Gibbs free energy with surface area in the system CuO–H2O. Data from Schindler et al. (Reference Schindler, Althaus, Hofer and Minder1965).

Such relationships are not limited to pairs or sets of crystalline phases. The precipitation of amorphous SiO2 from supersaturated solutions is commonly explained by the markedly lower surface energy of SiO2(am) than that of SiO2(quartz) (Konhauser, Reference Konhauser2006). The difference in the surface energies, on the order of a magnitude, causes precipitation of SiO2(am) and suppression of the supersaturation with respect to SiO2(quartz) to such a degree that quartz does not form at all.

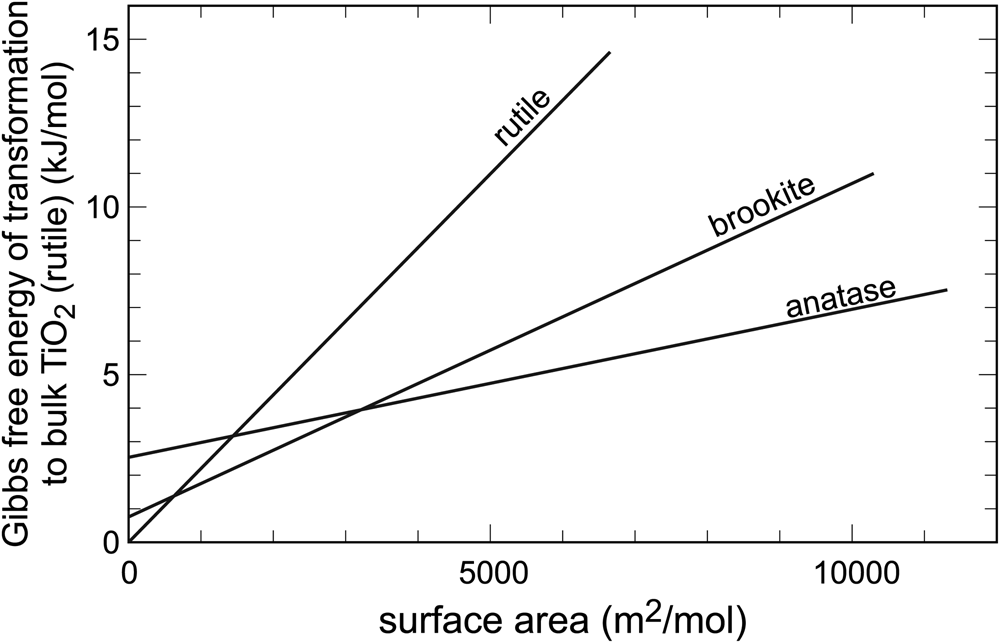

In systems with abundant polymorphism, the relationships among the individual phases can be more complex. In the system TiO2, there are three minerals: rutile, anatase and brookite. They are all fairly common, rutile being the one with the most occurrences. Rutile is, indeed, the most stable polymorph, but only in the bulk state. Upon gradual decrease of particle size, two crossovers are encountered (Fig. 2), both positioned at relatively low surface areas (< 4000 m2⋅mol–1). Hence, the TiO2 particles do not have to attain very small sizes in order to stabilise the polymorphs anatase or brookite. The first polymorph stabilised by surface area is anatase and, at yet higher surface areas, it is brookite. The calorimetric measurements of Ranade et al. (Reference Ranade, Navrotsky, Zhang, Banfield, Elder, Zaban, Borse, Kulkarni, Doran and Whitfield2002) agree with the syntheses (e.g. Zhang and Banfield, Reference Zhang and Banfield1998) where the finely divided initial products are made of a mixture of rutile and anatase, but coarsen progressively to rutile. They also agree with observations that leucoxene, a mineral mixture produced by weathering of Ti-bearing minerals, especially ilmenite and titanomagnetite, consists mostly of rutile and anatase, perhaps also brookite (e.g. Tyler and Marsden, Reference Tyler and Marsden1938; Weibel, Reference Weibel2003), with additional goethite (α-FeOOH). Voluminous materials research literature also supports the thermodynamic considerations. Nanoparticles of rutile, anatase and brookite can be synthesised by variations of the starting chemicals and modification of the solution composition, but coarsening leads invariably to rutile (e.g. Reyes-Coronado et al., Reference Reyes-Coronado, Rogríguez-Gattorno, Espinosa-Pesqueira, Cab, de Coss and Oskam2008).

Fig. 2. Variations of Gibbs free energy with surface area in the system TiO2. Data from Ranade et al. (Reference Ranade, Navrotsky, Zhang, Banfield, Elder, Zaban, Borse, Kulkarni, Doran and Whitfield2002).

There are a number of phases in the system Fe2O3–H2O, many of them with great abundance and significance for natural and man-made field systems. Extensive thermodynamic measurements (Navrotsky et al., Reference Navrotsky, Mazeina and Majzlan2008) showed that hematite (α-Fe2O3) and goethite are the stable phases, with a finely balanced equilibrium. They both have relatively large surface energies (Fig. 3) and become metastable with respect to other Fe2O3 or FeOOH polymorphs at relatively low surface areas. The least stable compound in the system, the mineraloid ferrihydrite, is considered to be metastable but, in reality, seems to have such a low surface energy that it is stable, at its usual small particle size, with respect to most Fe2O3 or FeOOH polymorphs (Fig. 3). Within the measurement uncertainties, it is stable with respect to goethite and akaganeite at high surface areas (Fig. 3). Hiemstra (Reference Hiemstra2015) showed that the surface enthalpy of ferrihydrite (0.11 J⋅m–2) is much lower than that of hematite (1.9 J⋅m–2). Using measurements (e.g. Snow et al., Reference Snow, Lilova, Radha, Shi, Smith, Navrotsky, Boerio-Goates and Woodfield2013) or estimates for surface entropies, Hiemstra (Reference Hiemstra2015) argued that ferrihydrite becomes thermodynamically unstable only when its particles exceed 8 nm; below this size, they appear to be stable and can persist for a long time. Ferrihydrite can be stabilised by adsorption of anions such as phosphate or arsenate. This effect can be seen in terms of kinetics, as diminution of the transformation rate (e.g. Das et al., Reference Das, Hendry and Essilfie-Dughan2011) or alternatively as bulk stabilisation of a thermodynamic phase (Majzlan, Reference Majzlan2011).

Fig. 3. Variations of Gibbs free energy with surface area in the system Fe2O3–H2O. Data from Navrotsky et al. (Reference Navrotsky, Mazeina and Majzlan2008) and Hiemstra (Reference Hiemstra2015).

Similar measurements have been done in the system Al2O3–H2O (McHale et al., Reference McHale, Auroux, Perrotta and Navrotsky1997; Majzlan et al., Reference Majzlan, Navrotsky and Casey2000). The synthetic γ-Al2O3 is stabilised by its high surface area with respect to corundum (α-Al2O3). This conclusion agrees with observations in Nature, for example the fact that atmospheric ultrafine Al2O3 particles belong to the γ-Al2O3 phase (e.g. Jefferson, Reference Jefferson, Brown, Collings, Harrison, Maynard and Maynard2000). Fine-grained alumina polymorphs, especially the γ phase, find extensive use in various branches of materials science and attest their stability with respect to corundum (Levin and Brandon, Reference Levin and Brandon1998). The calorimetric data agree with careful solubility studies (e.g. Wesolowski and Palmer, Reference Wesolowski and Palmer1994) that documented a difference in solubility product of gibbsite of ≈0.4 log units in acid-washed and untreated samples. The difference was assigned to the removal of fine particles by the acid.

The surface-area effects have been documented for manganese oxides (Birkner and Navrotsky, Reference Birkner and Navrotsky2017), iron and cobalt spinels (Fe3O4 and Co3O4) and related phases (Navrotsky et al., Reference Navrotsky, Ma, Lilova and Birkner2010) and olivine (Mg2SiO4) (Chen and Navrotsky, Reference Chen and Navrotsky2010). These studies bear more relevance to materials science or deep Earth, not necessarily to near-surface environments. Surface-area effects could influence some metamorphic minerals and processes (Penn et al., Reference Penn, Banfield and Kerrick1999). In these cases, however, it could be assumed that the growth of the newly formed phases is relatively rapid and leaves little space for long-lasting impact of the surfaces or interfaces.

Surface-area effects versus metastability

The phases which are stable in their bulk form have consistently the highest surface energies. The consequence is that, if there are other phases in such systems and their metastability margin is not too large, there will be free energy crossovers. Metastable phases have lower surface energies and should be preferred during nucleation (Navrotsky, Reference Navrotsky2004). Such effects can be expected in essentially every oxide system.

Hydrated phases tend to have lower surface energies than their anhydrous counterparts. The hydrated phases will therefore be preferred and stabilised by their surface energies and could be favoured in the near-surface environments.

An important corollary of these statements is that the phases, metastable in their bulk form, will become stable in a finely divided form. Hence, in this case, metastability is suppressed and what precipitates is actually stable. The stabilisation occurs, of course, only if all participating phases have the same surface area. Otherwise, the finely divided metastable phase continues to be metastable with respect to the bulk stable phase, although it is being stabilised by its surface energy.

For simple systems other than oxides, the experimental or computational results on their surface energies are limited. Surface energy of pyrite (Raichur et al., Reference Raichur, Wang and Parekh2001; Arrouvel and Eon, Reference Arrouvel and Eon2018) is comparable to those of the iron oxides. However, a systematic view of the equilibria between the iron sulfides, including the surface-area effects, is missing. It could be only assumed that the amorphous FeS precipitates that convert to mackinawite (Michel et al., Reference Michel, Antao, Chupas, Lee, Parise and Schoonen2005) and further to pyrite, are controlled by a similar driving force as the ferrihydrite–goethite or ferrihydrite–hematite transformations. Some microbial cultures have been observed to precipitate nanocrystals of sulfides that are considered to be metastable in the bulk form (Sitte et al., Reference Sitte, Pollok, Langenhorst and Küsel2013).

Surface energies of sulfates, carbonates and chlorides are one to two orders of magnitude smaller than those observed for oxides or sulfides (cf. Söhnel, Reference Söhnel1982). In such cases, energy crossover could still be encountered but the stabilisation energy would be negligible.

Kinetic barriers for the precipitation of the stable phases

One of the simplest reasons for the formation of metastable secondary minerals is the kinetic hindrance of the stable ones (e.g. Morse and Casey, Reference Morse and Casey1988; Steefel and van Cappellen, Reference Steefel and van Cappellen1990). In this case, the aqueous solutions can build up the concentration of cations and anions up to that needed to precipitate metastable phases. Indeed, many stable phases (in different systems) are characterised by dense, highly polymerised structures which do not readily form from an aqueous solution. Such systems follow Ostwald's step rule, visiting a number of metastable, intermediate states before reaching the stable one.

As examples, consider the stable phases in the systems Fe2O3–As2O5–H2O, scorodite (FeAsO4⋅2H2O), CuO–As2O5–H2O, olivenite [Cu2(OH)AsO4], and Fe2O3–Sb2O5, tripuhyite (FeSbO4). These systems are relevant to many sites with mine wastes. Calculation of saturation indices for these phases in more than one thousand samples of contaminated water worldwide (Fig. 4) shows that supersaturation is common. For olivenite and scorodite, the saturation indices reach values up to +6 and attest to the possibility that a less polymerised, metastable structure can form faster. Tripuhyite and the secondary antimonates represent a specific case. The aqueous solutions analysed are always supersaturated with respect to tripuhyite, considered to be the ‘ultimate sink’ of Sb in near-surface environments (Leverett et al., Reference Leverett, Reynolds, Roper and Williams2012). Field observations show that tripuhyite forms only very slowly (Majzlan et al., Reference Majzlan, Števko and Lánczos2016a) and is preceded by a series of phases with greater solubility and lesser stability (e.g. Borčinová-Radková et al., Reference Borčinová-Radková, Jamieson and Campbell2017).

Fig. 4. Saturation indices of acidic and neutral mine drainage waters with respect to three stable minerals. For formulae and details, see text.

Thus, supersaturation with respect to metastable phases can be reached if the nucleation and precipitation of the stable phases is too slow. Such situations may arise in portions of oxidation zones or mine wastes that are particularly rich in metals. Supersaturation of the entire volume of pore solutions in mine wastes is unlikely (e.g. Drahota et al., Reference Drahota, Filippi, Ettler, Rohovec, Mihaljevič and Šebek2012) but can be achieved in micro-environments or by processes of surface precipitation. Gräfe et al. (Reference Gräfe, Beattie, Smith, Skinner and Singh2008) observed that the surfaces of kaolinite [Al2Si2O5(OH)4], jarosite [KFe3(SO4)2(OH)6] and goethite can promote nucleation of euchroite- [Cu2(OH)AsO4⋅3H2O] and clinoclase [Cu3(AsO4)(OH)3]-like precipitates; both of these copper arsenates are metastable with respect to olivenite. Similarly, surfaces of birnessite [(Na,Ca,K)xMn2O4⋅nH2O] promoted crystallisation of a krautite [Mn(AsO3OH)⋅H2O]-like phase (Tournassat et al., Reference Tournassat, Charlet, Bosbach and Manceau2002) and the surfaces of goethite facilitated precipitation of a metastable uranyl arsenate [UO2(H2AsO4)2⋅H2O] (Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Cai, Yang, Liu, Chen, Lang, Wang and Wang2017). Jia et al. (Reference Jia, Xu, Fang and Demopoulos2006) observed precipitation of amorphous FeAsO4⋅nH2O on the surface of ferrihydrite and ascribed the process to early surface complexation of arsenate on the surface of the iron oxide, followed by re-arrangement and initiation of surface precipitation. Such mechanisms could also operate extensively in the pristine critical zone where undersaturation with respect to many secondary oxysalts (e.g. sulfates and arsenates) is the rule but the surfaces available for adsorption and precipitation are abundant.

Nanoparticles can be stabilised through their low surface energy and possibly further growth via orientated attachment (e.g. Cölfen and Antonietti, Reference Cölfen and Antonietti2005; Zhou and O'Brien, Reference Zhou and O'Brien2008; Yuwono et al., Reference Yuwono, Burrows, Soltis and Penn2010). Such nanoparticles can initially form by surface precipitation or by condensation of clusters. Large clusters with many metal atoms are well known for Al (Keggin cluster, Bottero et al., Reference Bottero, Axelos, Tchoubar, Cases, Fripiat and Fiessinger1987), U6+ (e.g. Burns and Nyman, Reference Burns and Nyman2018), or Nb (Friis and Casey, Reference Friis and Casey2018) and could play a role in the formation of metastable minerals. Ferrihydrite is inferred to consist structurally of ferric Keggin-like clusters (Michel et al., Reference Michel, Ehm, Antao, Lee, Chupas, Liu, Strongin, Schoonen, Phillips and Parise2007). Thus, formation of nanoparticles, their growth or transformation is also linked to surface energy of the phases involved.

Crystallisation from gels

Formation of metastable oxysalts could be effortlessly ascribed to kinetic hindrance of the stable-phase crystallisation. There are plentiful examples, however, where experiments show that the kinetic barriers are small and yet, metastable phases form readily.

There are several minerals in the system Cu4(OH)6SO4–H2O: Cu4(OH)6SO4 (brochantite); Cu4(OH)6SO4⋅H2O (posnjakite); and Cu4(OH)6SO4⋅2H2O (langite and wroewolfeite). There are no thermodynamic data for wroewolfeite, but among the three others, langite is the least stable, by a significant margin (17.5 kJ⋅mol–1 with respect to brochantite, Alwan and Williams, Reference Alwan and Williams1979; Majzlan et al., Reference Majzlan, Števko, Chovan, Luptáková, Milovská, Milovský, Jeleň, Sýkorová, Pollok, Göttlicher and Kupka2018b). Posnjakite and brochantite can be synthesised easily and precipitate readily from aqueous solutions (e.g. Yoder et al., Reference Yoder, Agee, Ginion, Hofmann, Ewanichak, Schaeffer, Carroll, Schaeffer and McCaffrey2007), implying that the kinetic barrier for crystallisation of the stable phases is small. The surface-energy arguments do not apply, as mentioned above, because the surface energies of such phases are similar and small. All this means that langite should not form but it does, at some sites in copious amounts as the most abundant mineral.

Investigation of the underground spaces at Ľubietová-Podlipa, Slovakia (Fig. 5, Majzlan et al., Reference Majzlan, Števko, Chovan, Luptáková, Milovská, Milovský, Jeleň, Sýkorová, Pollok, Göttlicher and Kupka2018b), where langite currently forms, explained the basic features of this process. Langite does not crystallise directly from an aqueous solution, although it seems to be close to equilibrium with it. Instead, langite forms slowly from a thick gel that lines the entire floor of the old adit (Fig. 5). Inside the mine, the gel, ~1 cm thick, is transparent and looks like blue ice because it lies on the surface of a water stream. X-ray absorption spectroscopy indicates that the local structure of this gel is langite-like (Majzlan et al., Reference Majzlan, Števko, Chovan, Luptáková, Milovská, Milovský, Jeleň, Sýkorová, Pollok, Göttlicher and Kupka2018b). When taken to the laboratory, this gel turns slowly to a liquid and leaves a bluish precipitate behind. Under natural laboratory conditions of steady temperature and humidity, the gel produces millimetre-sized blue langite crystals.

Fig. 5. Photographs from an adit in Ľubietová, Slovakia, with masses of blue gels that crystallise langite and green malachite masses. The photograph (b) is a detail from (a).

Similar copper-rich gels were observed elsewhere in the field, although not very often. Frédéric et al. (Reference Frédéric, Dold and Fontboté2012) reported gels that precipitate copper sulfates, chlorides and carbonates in Chuquicamata, Chile. Copper-rich gels were also described from mining sites in Ireland (Moreton and Aspen, Reference Moreton and Aspen1993) and Wyoming, USA (Williamson, Reference Williamson1994). A more extensive description of a ‘copper-bearing silica gel’ from a Tankardstown mine in Ireland (Moreton, Reference Moreton2007) documented its relation to langite and chrysocolla [Cu2-xAlx(H2-xSi2O5)(OH)4⋅nH2O] from this mine. Malachite [Cu2(CO3)(OH)2] is also present, just like at the site in Ľubietová.

Synthetic copper-bearing gels were investigated early on, for example by Finch (Reference Finch1914) (as “jellies”) with copper acetate, ammonia and manganese sulfate. Delafontaine (Reference Delafontaine1896) experimented with other elements and concluded that gels can also be formed when yttrium acetate and ammonia are mixed. More recently, Henry et al. (Reference Henry, Bonhomme and Livage1996) precipitated nanocrystalline posnjakite from copper-acetate–sulfate gels and investigated their structure.

Other secondary minerals form from such gels as well. The synthesis of krautite [Mn(AsO3OH)⋅H2O] commences with mixing of two solutions and the immediate formation of a thick gel (Deiss, Reference Deiss1914; Buckley et al., Reference Buckley, Bramwell and Day1990). With progressing time, radial aggregates of krautite crystals form from the gel (Fig. 6) and after a few weeks or months, the gel turns to liquid and crystals sink to the bottom of the flask. Higher temperatures speed the process up but the transient gel still occurs. We found that some other members of the krautite group, for example koritnigite, can be synthesised exactly in the same way. X-ray absorption experiments (Fig. 7) on the Mn–As gel and the resulting krautite crystals showed that the local structure of the gel, even a few minutes after its formation, is already krautite-like.

Fig. 6. Gelatinous Mn–As-bearing substance with aggregates of krautite crystals. The gel was prepared by mixing two solutions (see Buckley et al., Reference Buckley, Bramwell and Day1990) about 6 weeks before the photograph was taken.

Fig. 7. Comparison of the EXAFS data for crystalline krautite and a fresh gel that turns within weeks or months into krautite (see also Fig. 6). The gel was prepared 20 minutes before the measurement, frozen at 15 K, and measured.

The existence of WO3⋅xFe2O3⋅nH2O gels was documented by Tarassov and Tarassova (Reference Tarassov and Tarassova2018) and presumed by Števko et al. (Reference Števko, Sejkora, Malíková, Ozdín, Gargulák and Mikuš2017). In both cases, the gels are thought to be precursors or companions to tungstite (WO3⋅H2O), hydrotungstite (WO3⋅2H2O) and related minerals. Wei et al. (Reference Wei, Zhu, Zhang, Wang and Liu2013) noted that vigorous stirring of the starting solutions “was important to suppress the formation of gelatinous, poorly crystallized arsenate phase” during the synthesis of annabergite [Ni3(AsO4)2⋅8H2O] and erythrite [Co3(AsO4)2⋅8H2O].

Crystallisation from X-ray amorphous solid precursors

Apart from viscous gels that tend to turn to liquid, metastable minerals can form slowly from solid, disordered precursors. An example of a site with such minerals are the medieval dumps from silver mining in Kaňk near Kutná Hora in the Czech Republic. These dumps can be divided broadly into clayey and rocky. The clayey dumps contain nodules of the mineral bukovskýite [Fe2(AsO4)(SO4)(OH)⋅9H2O], up to a size of 1 metre. The rocky dumps contain abundant kankite [FeAsO4⋅3.5H2O], zýkaite [Fe4(AsO4)3(SO4)(OH)⋅15H2O] and parascorodite [FeAsO4⋅2H2O] (e.g. Ondruš et al., Reference Ondruš, Skála, Viti, Veselovský, Novák and Jansa1999). Scorodite, the most stable phase, is uncommon.

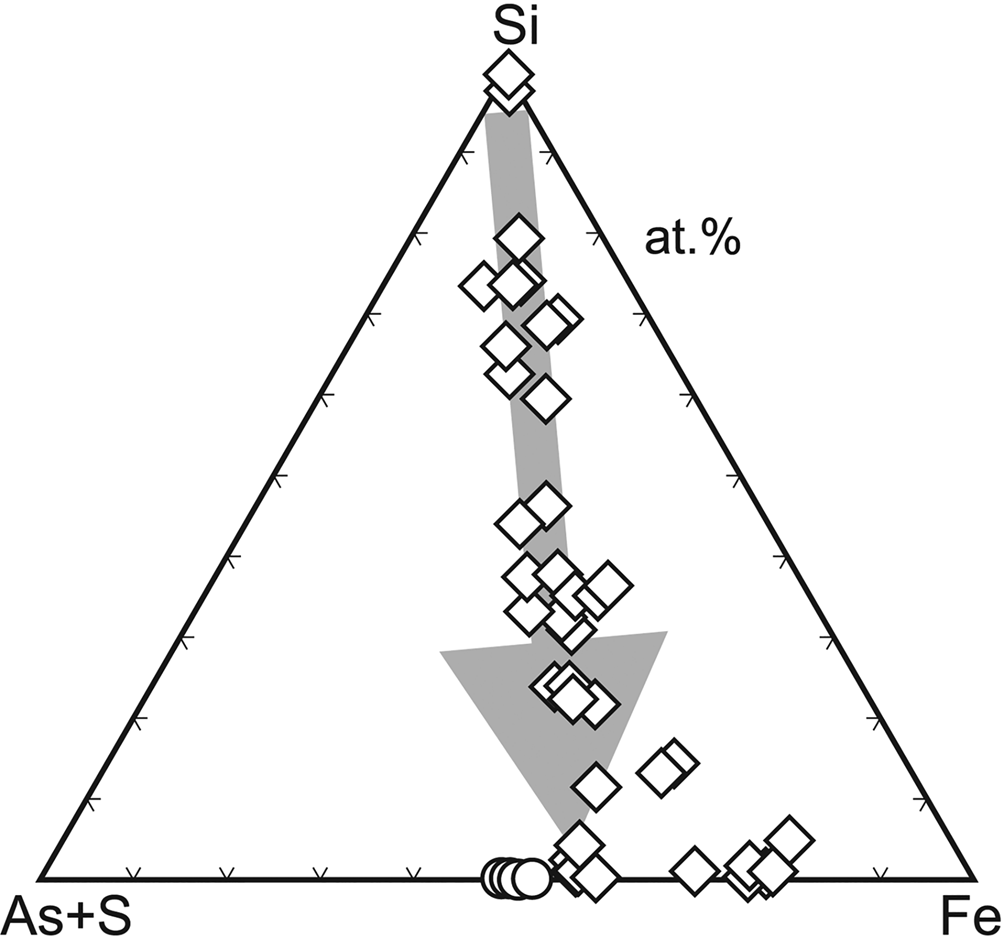

Microscopic and analytical work (Loun, Reference Loun2010; Majzlan et al., Reference Majzlan, Lazic, Armbruster, Johnson, White, Fisher, Plášil, Loun, Škoda and Novák2012) showed that bukovskýite forms from solid ‘gels’ or ‘resins’ whose composition varies widely (Fig. 8). During the evolution from SiO2–Al2O3 dominated compositions towards those comparable to that of bukovskýite, these substances maintain approximately the Fe:As:S ratio of 2:1:1 and eventually convert to the compact crystalline bukovskýite. These gels or resins digest and incorporate the entire content of silicates and sulfides in the dumps. The end product, the bukovskýite nodules, are completely free of such minerals. We found no evidence that the crystallising nodules are able to push out or to displace mechanically the original fine-grained material of the dumps. The process is therefore of a purely chemical nature and generates large amounts of metastable secondary minerals.

Fig. 8. Evolution of the chemical composition of X-ray amorphous solids (diamonds) that produce compact bukovskýite (circles) at Kaňk, Czech Republic. Data are electron microprobe analyses from Loun (Reference Loun2010) and Majzlan et al. (Reference Majzlan, Lazic, Armbruster, Johnson, White, Fisher, Plášil, Loun, Škoda and Novák2012).

Another example of such processes is the weathering of complex sulfides, such as minerals of the tetrahedrite–tennantite [(Cu,Fe,Zn,Hg,Ag)12(Sb,As)4S13] group (Majzlan et al., Reference Majzlan, Kiefer, Herrmann, Števko, Chovan, Lánczos, Sejkora, Langenhorst, Lazarov, Gerdes, Radková, Jamieson and Milovský2018c; Keim et al., Reference Keim, Staude, Marquardt, Bachmann, Opitz and Markl2018). In the initial stages of such weathering, X-ray amorphous, nanocrystalline products are formed. They are unstable and slowly convert to crystalline minerals, mostly arsenates, of which some are also metastable. The transient X-ray amorphous materials are related to the antimony-bearing phases with pyrochlore structure, such as oxycalcioroméite (Ca2Sb2O6O) or bindheimite (Pb2Sb2O6O). Similar materials were also reported recently by Đorđević et al. (Reference Đorđević, Kolitsch, Serafimovski, Tasev, Tepe, Stöger-Pollach, Hofmann and Boev2019) from weathering of realgar-rich tailings which are rich in Sb but depleted in Fe. Our on-going studies indicate the presence of similar materials during weathering of Hg-tetrahedrite. In all cases, these materials are rich in As and retain large parts of this element. One of the intriguing questions is the position of arsenic in these materials because the pyrochlore structure has no tetrahedral sites available for As5+. In other words, the X-ray amorphous material houses an element whose coordination preferences deviate strongly from what is available. It could be therefore assumed that the metastability of the initial X-ray amorphous material is so pronounced that its recrystallisation and re-arrangement can lead to a wide range of arsenates, including those that are metastable.

Biologically-driven disequilibria

Biologically-controlled mineralisation (see Konhauser, Reference Konhauser2006) may generate metastable minerals that serve a specific biological purpose but such mineralisation is rarely of relevance for oxidation zones or mine wastes. The products of the biologically-induced mineralisation, either passive or facilitated (Konhauser, Reference Konhauser2006), are much more voluminous and typical for some environments of mine wastes, for example acid mine drainage (AMD). In this case, however, the microorganisms (e.g. Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans) accelerate the reactions and reduce the deviation from equilibrium; in other words, they bring such systems nearer to equilibrium. Metastable minerals, such as ‘green rusts’ [e.g. the minerals fougèrite, Fe2+4Fe3+2(OH)12[CO3]·3H2O, trébeurdenite, Fe2+2Fe3+4O2(OH)10CO3·3H2O and mössbauerite, Fe3+6O4(OH)8[CO3]·3H2O; Mills et al., Reference Mills, Christy, Génin, Kameda and Colombo2012], ferrihydrite (FeOOH⋅nH2O) or schwertmannite [Fe8O8(OH)6SO4], may precipitate, but their formation can be attributed to the surface-energy effects, not to the microorganisms themselves. In addition, the cells or their metabolic products may provide nucleation sites for metastable or stable minerals and lower the energetic barrier for nucleation and growth.

In some cases, however, the action of microorganisms can generate a disequilibrium situation which would be difficult to attain otherwise. In AMD water rich in Fe2+ and As3+, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans can oxidise only Fe2+ but not As3+ (Egal et al., Reference Egal, Casiot, Morin, Parmentier, Bruneel, Lebrun and Elbaz-Poulichet2009). The resulting Fe3+/As3+ solution, in a strong redox disequilibrium, can precipitate the ferric arsenite tooeleite [Fe63+(As3+O3)4(SO4)(OH)4⋅4H2O] (Majzlan et al., Reference Majzlan, Dachs, Bender Koch, Bolanz, Göttlicher and Steininger2016b). Other organisms, such as Thiomonas sp., oxidise both Fe2+ and As3+ and induce the formation of poorly crystalline ferric arsenates (Morin et al., Reference Morin, Juillot, Brunneel, Personnè, Elbaz-Poulichet, Leblanc, Ildefonse and Calas2003). Another pathway to such disequilibrium situation would be dissimilatory reduction of As5+ in scorodite by Shewanella sp. (Revesz, Reference Revesz2015).

Conclusions

Field observations show that metastable minerals in the near-surface environments can form by precipitation from a homogeneous aqueous solution, following the Ostwald's step rule. Considering the structural relationship among polymorphs or chemically related minerals, the rule could be alternatively formulated as preferred initial formation of structurally simple phases that may transform to structurally more complex phases. An implication is also that the simple structures have lower surface energies. There is no requirement of a structural relationship between the initial phase(s) and the precursor.

There are many options other than nucleation and crystallisation from homogeneous aqueous solutions, as exemplified in this work. Formation of nanoparticles, stabilisation through surface energy, and further growth via oriented attachment are possibilities often encountered in the near-surface environments. Nanoparticles could form by homogeneous or heterogeneous nucleation, surface precipitation, or by condensation of clusters. Formation of nanoparticles, their growth or transformation is also linked to surface energy of the phases involved.

In underground spaces, we commonly find gelatinous or solid X-ray amorphous substances which are apparently weathering products of primary hydrothermal minerals. The fate of such substances is not clear but they certainly bear the potential to crystallise secondary minerals, including the metastable ones. Because of their transient nature and localisation in the depth of mines or mining waste, they remain hidden and are difficult to find, characterise, and understand. Such materials can be common and constitute precursors to many metastable secondary minerals in mine waste. They are well known from synthetic chemistry but are difficult to find or easy to overlook in the field.

The metal concentrations in the oxidation zones and mine wastes is often so high that the processes of metastable-mineral formation can be observed directly. The transient substances can be sampled and inspected by techniques such as X-ray absorption spectroscopy or electron microscopy. Finally, many similar processes may operate in general in the uncontaminated critical zone but they may be more difficult to capture and describe in the field.

Acknowledgements

I am thankful to two anonymous reviewers for their constructive and detailed comments on the manuscript. Examples brought in this work are results from several projects funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, in collaboration with many students and colleagues, especially M. Chovan, Ľ. Jurkovič, M. Števko, and J. Plášil. I appreciate also the support and many measurement times at the ANKA synchrotron in Karlsruhe, especially to J. Göttlicher, R. Steininger, and S. Mangold, including for the yet unpublished data on krautite presented in this publication.

The annual Hallimond lecture is a tribute to Arthur Francis Hallimond (1890–1968) in recognition of his contribution to the science of mineralogy, particularly in the fields of ore mineralogy and instrument design (

The annual Hallimond lecture is a tribute to Arthur Francis Hallimond (1890–1968) in recognition of his contribution to the science of mineralogy, particularly in the fields of ore mineralogy and instrument design (