Childhood obesity is a significant public health problem. Among Canadian youth, one child in four is overweight or obese(Reference Shields1). Unfortunately, weight-loss interventions in obese children and youth have been largely ineffective(Reference Summerbell, Ashton, Campbell, Edmunds, Kelly and Waters2). Thus, efforts to combat the childhood obesity epidemic will likely need to focus on obesity prevention rather than obesity treatment. It is essential to fully understand the factors that contribute to childhood obesity to create optimal obesity prevention strategies and policies.

Existing research on the aetiology of obesity has focused on obesity-promoting (obesogenic) behaviours and has largely ignored the environmental factors that may dictate or mediate these behaviours(Reference Cummins and Macintyre3). One aspect of the environment that may influence obesogenic behaviours is access to food retailers. To illustrate, some neighbourhoods may have a preponderance of food retailers and restaurants selling unhealthy, energy-dense foods that promote obesity. A state-level analysis conducted in the USA found that the density of neighbourhood fast-food retailers was positively associated with obesity(Reference Maddock4). A large cohort study of adults reported that a greater number of neighbourhood supermarkets was associated with a lower likelihood of obesity, while a greater number of convenience stores was associated with a higher likelihood of obesity(Reference Morland, Diez Roux and Wing5). These findings highlight the potential relevance of the food retail environment.

To our knowledge, only two studies have examined the relationship between the food retailer environment and adiposity in children and youth. Burdette and Whitaker(Reference Burdette and Whitaker6) did not find a relationship between the proximity to fast-food restaurants and overweight in pre-school children living in a low-income neighbourhood in Cincinnati, Ohio. Similarly, a longitudinal study of kindergarten students across the USA found that the number of fast-food restaurants, full-service restaurants and convenience stores in the neighbourhood was not related to obesity in the third grade(Reference Sturm and Datar7). It is noteworthy that these studies were conducted in young children who do not have the same degree of dietary autonomy as older children. Furthermore, results from these American studies may not be transferable to other countries or populations. Finally, because students spend a considerable portion of their day at school and because food retailers cluster around schools(Reference Austin, Melly, Sanchez, Patel, Buka and Gortmaker8), the food environment surrounding schools may be an important determinant of obesogenic behaviours in youth.

The aim of the present study was to determine whether a relationship exists between the food retailer environment and rates of overweight and obesity in Canadian youth. Specifically, the study considered whether the number of different types of food retailers in the environment surrounding schools and the broader neighbourhood in which youth live is related to obesity rates. It was hypothesized that the number of neighbourhood food retailers that sell primarily energy-dense foods (fast-food restaurants, convenience stores and coffee/doughnut shops) would be positively associated with overweight and obesity, while the number of retailers that tend to offer healthier food choices (such as sub/sandwich shops, full-service restaurants, grocery stores) would be negatively associated with overweight and obesity.

Experimental methods

Survey

The study sample involved Canadian students participating in the 2005/06 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey(Reference Roberts, Currie, Samdal, Currie, Smith and Maes9). The HBSC is a cross-national survey performed in collaboration with the WHO. The sampling approach used the school class as the unit of selection, with classroom grades chosen to reflect the distribution of students in grades 6–10 in the Canadian population. Schools were selected using a weighted probability technique to ensure that the sample was representative by regional geography and key demographic features (religion, community size, school size, language of instruction). Schools from each province and territory, as well as urban and rural locations, were represented. Youth attending private or special needs schools, incarcerated youth and youth not enrolled in school were excluded. Combined, these excluded individuals represent ∼9 % of the study age group in Canada(10). A total of 9672 students from 188 schools participated in the 2005/06 survey. Of the students selected for the study, 74·2 % completed the questionnaire, and their demographic profile was representative of Canadians in the same age range. Ethics approval was obtained from the Queen’s University General Research Ethics Board. Consent was obtained at the school board and school levels, as well as from students and their parents.

Measurement of neighbourhood food retailers

Classification of food retailer types

Information was obtained on the location and type of food retailers surrounding schools using the street addresses of the participating schools. This was obtained through an Internet-based food retailer database (www.yellow.ca). To ensure that each food retailer was classified into mutually exclusive categories, a classification strategy was created whereby chain retailers were assigned to one of the categories of food retailers. Information was initially collected on twelve types of food retailers, which were then collapsed to obtain the six categories of food retailers used in the analysis. Large chain retailers were categorized into the six groups first, and the remaining independent retailers were subsequently categorized. A variable measuring the total number of food retailers was also obtained by summing the individual food retailers.

Distance of food retailers from schools

The number and type of food retailers within a 1 km distance was chosen to represent food sources students would have close access to. This distance was chosen because it corresponds to an approximate 10–15 min one-way walk(Reference Austin, Melly, Sanchez, Patel, Buka and Gortmaker8, Reference Apparicio, Cloutier and Shearmur11). It was expected that students were able to access these retailers on their way to and from school and during breaks in the school day. In addition to exposure to food retailers within close proximity to schools, information was also collected on food retailers within the broader school neighbourhood. The number and type of food retailers within a 5 km radius was chosen to represent food sources that students and their families would have close access to in their neighbourhoods. A sensitivity analysis from a previous HBSC study in Canada showed no differences in area-level socio-economic status (SES) between the 1 km and 5 km distance(Reference Simpson, Janssen, Craig and Pickett12). Therefore, the 5 km distance was chosen because it would be more inclusive of residences of students attending the schools.

Classification of food retailer exposure groups

For the 1 km radius, schools were categorized into two groups for each food retailer type: those with no exposure to food retailers and those with exposure to one or more retailer. At this distance we felt it was not the number of food retailers that is important per se, but rather whether students had access to that type of food retailer. For each food retailer type, exposure was determined by whether there was a given type of food retailer within a 1 km radius. For example, a school was considered exposed to full-service restaurants if there was at least one full-service restaurant within the 1 km radius. This was repeated for fast-food restaurants, sub/sandwich shops, doughnut/coffee shops and convenience stores. Similarly, a total food retailer index was created, whereby schools were divided into two groups indicating whether they were exposed or not exposed to any food retailers.

Food retailers within a 5 km radius of the schools were classified into four groups: the first group had no retailers and the remainder was divided into tertiles, herein referred to as low, medium and high exposure categories. This was done for all six types of food retailers. A total food retailer index was also created, whereby a category was created for schools with no exposure to any food retailers and the remaining schools with exposure to at least one food retailer were divided into tertiles, indicating low, medium and high exposure.

For the 5 km distance, a population food retailer density was also calculated by dividing the number of each type of retailer by the number of people living within the 5 km radius. The number of people living within 5 km of schools was obtained from PCensus (2001 Census of Canada Profile Data, version 2001; Tetrad Computer Applications Inc., Bellingham, WA, USA) based upon the schools’ civic addresses. The number of food retailers was divided by the population within 5 km and was multiplied to obtain the number of retailers per 10 000 people. The density measure took into consideration the size of the population sharing access to the various food retailers, as performed in a number of similar studies(Reference Sturm and Datar7, Reference Moore and Diez Roux13–Reference Cummins, McKay and MacIntyre15).

Measurement of neighbourhood-level covariates

Area-level SES and urban–rural status could potentially explain differences in the availability of food retailers. Previous studies have shown a consistent relationship between area-level SES and adiposity status in Canadian youth(Reference Oliver and Hayes16–Reference Janssen, Boyce, Simpson and Pickett18). Using methods developed by Oliver and Hayes(Reference Oliver and Hayes16), the area-level SES was obtained for individuals living within 5 km of schools using PCensus for the 2001 Canadian Census. Values for median household income, unemployment rate and percentage of the population with less than a high school education were ranked for each of the schools and the sum of the rankings was obtained. This summed value was used to dichotomize the school neighbourhoods as high or low SES. Much of the existing research on the relationship between food retailers and overweight has taken place in largely urban areas. However, schools that participated in the HBSC varied in their geographical status. Urban–rural status of the participating schools was obtained through a postal code analyser using Statistics Canada data. Schools located in areas that had a population greater than 10 000 people were considered urban, while those with a smaller population were not considered urban, which was consistent with the definition used by Statistics Canada(19).

Measurement of individual-level variables

Overweight and obesity (outcome)

Students self-reported their height and weight on the HBSC survey, and this information was used to calculate their BMI (kg/m2). Overweight and obesity were defined using the age- and sex-specific BMI cut-off points recommended by the International Obesity Taskforce(Reference Cole, Bellizzi, Flegal and Dietz20). Youth whose BMI corresponded to the adult value of ≥25 kg/m2 were classified as overweight (including both overweight and obese), while those whose BMI corresponded to the adult value of ≥30 kg/m2 were classified as obese.

Covariates

Individual-level confounders included age and sex. Because physical activity is associated with lower levels of obesity(Reference Parsons, Power, Logan and Summerbell21), it was also considered as a potential confounder. Students were asked how many days per typical week they were physically active for at least 60 min, with options ranging from 0 to 7 d. The Family Affluence Scale, a measure of family wealth developed for use in the HBSC(Reference Currie, Samdal, Boyce and Smith22), was also included as a covariate. This scale is based on four questions regarding car ownership, bedroom sharing, holiday travel and computer ownership. Individual-level SES was considered a potential confounder because of its association with obesity(Reference Oliver and Hayes16, Reference Veugelers, Yip and Kephart23) and access to food retailers(Reference Reidpath, Burns, Garrard, Mahoney and Townsend14, Reference Block, Scribner and DeSalvo24–Reference Wang, Kim, Gonzalez, MacLeod and Winkleby26).

Statistical analysis

Spearman’s correlations were calculated to examine the relationship between the number of individual food retailers and the total food retailer index for the neighbourhoods of the participating schools. Regression analyses were performed to examine the association between food retailers and overweight. Multilevel modelling regression procedures were used to take into account the clustered nature of the data and to allow for simultaneous consideration of both individual-level and area-level variables as predictors of the overweight outcome(Reference Diez-Roux27). The Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) software package version 5·05 (Scientific Software International, Lincolnwood, IL, USA) was used to perform multilevel logistic regression. Overweight (including both overweight and obese youth) was the binary outcome considered in the logistic models.

A three-step modelling process was used. Initially, each covariate was examined bivariately with the outcome variables. At this stage, the individual-level variables were assessed to determine whether there were complex level-2 effects, whereby the relationship between individual-level variables and overweight differed across schools. No complex level-2 effects were found and the effects of individual level variables were treated as fixed across all schools. Thus, all models in the analysis were random intercept models. The second phase of the modelling process involved the creation of multivariate models. Covariates that were significantly related to the outcome variable (P < 0·05) in the bivariate analysis were considered in the multivariate models, which were created using a manual stepwise approach.

For the 1 km analysis, the variables were added in order starting with the lowest P value. In the 5 km analysis the average P value from the various exposure groups was used to determine the order in which the food retailers were entered into the model. The third phase of the modelling process involved the total food retailer index variable to determine if the combined effect of the food retailers was more strongly predictive of overweight and obesity than each retailer individually. Due to problems in converging multilevel models with several area-level variables included, the food retailers were not included, forced or retained in the stepwise multivariate models unless they were statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive characteristics

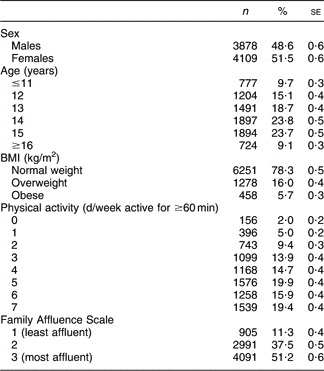

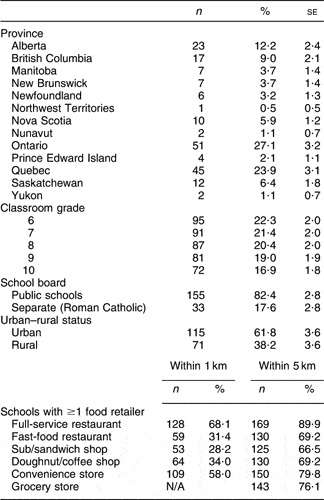

A total of 9672 students from 188 schools participated in the 2005/05 HBSC survey, but due to incomplete information, the analysis was limited to 7281 (75·2 %) students from 178 schools. A mean of forty-two students per school participated in the survey, with a range of one to 176 students per school. The average prevalence of overweight and obesity in students was 22·2 % across schools, and ranged from 0 to 53·8 %. The number of overweight and obese students is presented in Table 1. Of the individual-level variables listed in Table 1, only age was not significantly (P < 0·05) associated with overweight and obesity. Thus, all of the individual-level variables, with the exception of age, were included as covariates in the multivariate regression models. Descriptive details on the area-level variables are shown in Table 2. Of the area-level covariates, urban–rural status but not area-level SES was related to overweight; therefore, urban–rural status was also included as a covariate in the multivariate regression models.

Table 1 Individual-level demographic characteristics of the study participants: Canadian students participating in the 2005/06 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Survey

Table 2 Area-level demographic characteristics of the study participants: Canadian schools participating in the 2005/06 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Survey

N/A, not applicable.

Relationship between neighbourhood food retailers

Correlations among the various food retailers was assessed and ranged from 0·41 to 0·73 for food retailers within the 1 km radius and 0·79 to 0·93 for food retailers within the 5 km radius (data not shown). In general, the number of full-service restaurants was the most highly correlated with the total food retailer index, while the number of convenience stores and fast-food restaurants were the least correlated with the other food retailer types and the total food retailer index.

Relationship between food retailers and overweight

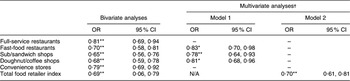

1 km Distance

As indicated in Table 2, full-service restaurants were the most common food retailer located within 1 km of schools, with over two-thirds of schools having at least one within 1 km. Sub/sandwich shops were the least common, with 28·2 % of the schools having at least one within 1 km. In the bivariate analyses, each type of food retailer and the total food retailer index were negatively associated (P < 0·05) with overweight (Table 3). In the first stepwise multivariate model (which did not consider the total food retailer index) fast-food restaurants, sub/sandwich shops and doughnut/coffee shops were included. Youth who had access to these types of food retailers within 1 km of their school were less likely to be overweight compared with youth who did not have access to these types of food retailers within 1 km of their school (Table 3). When the total number of food retailers was considered in a second multivariate model, the individual food retailer types no longer met the inclusion criteria to be included in the model. However, the students whose schools were above the median for the total food retailer index had a reduced likelihood of being overweight compared with the students whose schools were below the median for the total food retailer index (Table 3).

Table 3 Association between exposure to different types of food retailers within 1 km of schools and overweight: Canadian students participating in the 2005/06 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Survey

N/A, not applicable.

Odds ratio was significant: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01.

†Multivariate models were adjusted for sex, physical activity and family affluence. The total food retailer index was considered in Model 2 but not in Model 1. For the individual food retailers, the ‘no’ (0 retailers) exposure group served as the referent category while for the total food retailer index the group falling below the median served as the referent category.

– indicates not included in the final model.

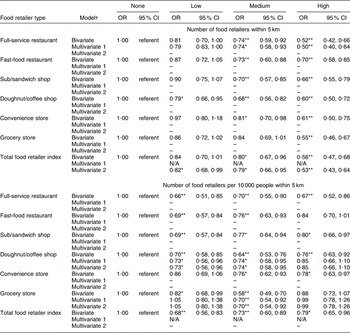

5 km Distance – number of retailers

Similar to the 1 km results, full-service restaurants were the most common and sub/sandwich shops the least common food retailer (Table 2). In the bivariate analyses, at least one of the non-referent exposure categories (low, moderate or high) for each type of food retailer and the total food retailer index were associated (P < 0·05) with a decreased likelihood of overweight (Table 4). When the initial multivariate model was fit for the number of food retailers at the 5 km distance, only full-service restaurants was included in the model (Table 4). Compared with attending schools in neighbourhoods with no full-service restaurants, participants attending schools in neighbourhoods with medium and high numbers of full-service restaurants were less likely to be overweight. When the total number of food retailers was considered in a second multivariate model, the individual food retailer types no longer met the inclusion criteria to be included in the model (Table 4).

Table 4 Association between exposure to different types of food retailers within 5 km of schools and overweight: Canadian students participating in the 2005/06 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Survey

N/A, not applicable.

Odds ratio was significant: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01.

†Multivariate models were adjusted for sex, physical activity and family affluence. The total food retailer index was considered in Model 2 but not in Model 1. For the individual food retailers, the ‘no’ (0 retailers) exposure group served as the referent category while for the total food retailer index the lowest quartile served as the referent category.

– indicates not included in the final model.

5 km Distance – number of retailers per 10 000 residents

In the bivariate analyses, at least one of the non-referent exposure categories (low, moderate or high) for each type of food retailer and the total food retailer index were associated (P < 0·05) with a decreased likelihood of overweight (Table 4). When the initial multivariate model was fit for the number of restaurants per 10 000 people at the 5 km distance, doughnut/coffee shops and grocery stores were included in the model such that students living in neighbourhoods with a moderate exposure to these two types of food retailers were less likely to be overweight than students with no exposure. Similar observations were made in the second multivariate model that considered the total food retailer index (Table 4).

Obesity outcome

The analyses for the overweight outcome (which included both overweight and obese youth) presented in Tables 3 and 4 were re-run comparing obese with normal-weight participants. Overall the results were comparable, although there were some slight variations in the types of food retailers that were included in the multivariate models.

Discussion

The key observation of the present study is that increased exposure to food retailers, both in the immediate school environment and in the broader neighbourhood, was not associated with increased odds of overweight and obesity in Canadian school-aged youth. This relationship was consistent across all food retailer types.

Findings of the study are inconsistent with the a priori hypothesis that exposure to certain types of food retailers (fast food, doughnut/coffee shops, convenience stores) would be associated with an increased relative odds of overweight and obesity. Furthermore, the findings contradict some of the previous literature examining the relationship between measures of adiposity and food retailers. A study by Maddock(Reference Maddock4) found that a high density of fast-food restaurants was associated with a higher prevalence of obesity throughout the USA, while our study found the opposite. Morland et al.(Reference Morland, Diez Roux and Wing5) found that grocery stores and convenience stores were associated with a higher prevalence of adult obesity, while supermarkets were associated with a lower prevalence of adult obesity. Conversely, Wang et al.(Reference Wang, Kim, Gonzalez, MacLeod and Winkleby26) reported that a higher density of grocery stores and closer proximity to supermarkets were both associated with a higher BMI, but in women only. Notable SES gradients in exposure to food retailers in the American setting may be a reflection of the larger income disparities found in comparison to Canada(Reference Ross, Dorling, Dunn, Henriksson, Glover, Lynch and Weitoft28, Reference Ross, Wolfson, Dunn, Berthelot, Kaplan and Lynch29). Additionally, there may be different proportions of chain and non-chain food retailers in Canada and the USA which may account for these differences.

Although our findings are dissimilar to most existing analogous research, they were consistent across distance, whether food retailers were considered together or separately, and also after taking population density into account. We speculate that having access to a variety of food retailers may be beneficial, at least within the Canadian context, because this increased access provides the individual with a broad variety of choices rather than forcing them to rely on a limited selection of options. It may not be the type of food retailer that is important per se, but the opportunity to select healthier choices that may explain our results. However, further research is needed to determine the mechanism behind this relationship.

It is possible that in our study the number of food retailers may have captured the effect of more complex features of the school and surrounding environment. Other aspects of the environment such as the availability of recreational facilities(Reference Norman, Nutter, Ryan, Sallis, Calfas and Patrick30, Reference Gordon-Larsen, Nelson, Page and Popkin31) and nearby parks(Reference Norman, Nutter, Ryan, Sallis, Calfas and Patrick30, Reference Cohen, Ashwood, Scott, Overton, Evenson, Staten, Porter, McKenzie and Catellier32) are associated with the frequency of physical activity and BMI in youth. It is plausible that the presence of food retailers is positively correlated with the presence of facilities that promote physical activity, which could explain the lower levels of overweight and obesity in schools that are close to various food retailers. The use of objective measures such as the 1 km and 5 km radii around schools may have good face value in describing the food environment, but it is less clear if objective measures accurately capture the impact of built environment on obesity. Recent studies have revealed that there are inconsistencies between how objective and perceived measures of the built environment relate to physical activity(Reference Boehmer, Hoehner, Deshpande, Brennan Ramirez and Brownson33, Reference McGinn, Evenson, Herring, Huston and Rodriguez34), although it is not known if the same is true for eating behaviours and obesity. It is likely that other unknown factors determine whether students choose to purchase food available to them. For example, the distinction between chain and non-chain restaurants may be important to youth, who may be more likely to purchase foods marketed by large chain retailers. Also, over time people may become accustomed to the food retailers within their environment and become less likely to frequent them. Due to the largely close-ended nature of the HBSC survey, we were unable to explore this hypothesis. The relationship between the objectively measured food environment, perceived environment and obesity has yet to be fully developed.

The present study has several limitations. First, we were unable to take into account internal sources of food within the schools, such as vending machines and cafeterias. These food sources may have been particularly important for rural schools, which have less access to external food retailers, and urban schools with policies on leaving school grounds during the school day. Future studies investigating the food environment around schools should include information on the availability and quality of internal food sources such as cafeterias and vending machines, and whether students consume foods brought from home. Furthermore, the HBSC survey did not include information on whether school policy allowed students to leave school property during breaks. With this information, the relationship between school food environment and obesity may become clearer. Second, because the students’ home addresses were not collected in the survey, the 5 km radius surrounding each school was used as a proxy for the neighbourhoods of the students attending that school. Some students lived outside this area, and the access to the food environment within 5 km of their home may have differed from that of their school. Third, we cannot make the assumption that the presence of food retailers was associated with the consumption of the foods they sold. Conclusions can only be made about the availability of the food retailers and measures of adiposity, rather than individual-level behaviours that may also be associated with negative health outcomes. Fourth, we only considered half of the energy balance equation. Environmental factors influencing physical activity levels were not considered in the study. Finally, because the heights and weights used to calculate BMI status were obtained through self-report, there was likely some non-differential misclassification bias that could have decreased the magnitude of the relationship between overweight/obesity and food retailers.

The results of our study revealed that the effect of the environment on overweight and obesity is complex. It appears that the effect of food environment on overweight and obesity in Canadian youth is notably different from what has been found in American studies. According to our results, policy interventions limiting the number and type of food retailers within the school environment may not be an effective strategy for the prevention and reduction of overweight and obesity in youth. Future research is needed to provide a greater understanding of the mechanisms behind this relationship as well as other environmental determinants of overweight and obesity in adolescents.

Acknowledgements

The submission represents original work that has not been published previously, is not currently being considered by another journal, and that following acceptance for Public Health Nutrition will not be published elsewhere in the same form, in English or in any other language. Each author has seen and approved the contents of the submitted manuscript. None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to declare. All of the authors have contributed substantially to the manuscript. Specifically, L.M.S., I.J. and W.P. contributed to the study conception and design. All authors contributed substantially to the interpretation of the results and data analyses. L.M.S. wrote the draft of the manuscript while I.J., W.P. and W.F.B. revised it for important intellectual content. The study was supported by research agreements with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (operating grant: 2004MEP-CHI-128223-C) and the Public Health Agency of Canada (contract: HT089-05205/001/SS) which funds the Canadian version of the WHO Health Behaviour in School-aged Children survey (WHO-HBSC). The WHO-HBSC is a WHO/Euro collaborative study. International Coordinator of the 2005–2006 study: Candace Currie, University of Edinburgh, Scotland; Data Bank Manager: Oddrun Samdal, University of Bergen, Norway. This publication reports data solely from Canada (Principal Investigator: W.F.B.). The authors would like to thank the researchers and participants involved in the HBSC survey. L.M.S. was partially supported by a fellowship from the Empire Life Insurance company. I.J. was supported by a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and an Early Researcher Award from the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation.