1. Introduction

Negative family communication is a risk factor for the onset and relapse of psychosis. Expressed Emotion (EE) measures both positive and negative aspects of relationships. High EE is rated when a close relative expresses high levels of criticism, hostility or intrusive overconcern – emotional overinvolvment (EOI). Patients with psychosis can experience high expressed emotion (EE) in a family environment [Reference Leff, Vaughn, Leff and Vaughn1], and can then more likely experience a psychotic relapse [Reference Bebbington and Kuipers2]. High EE also relates to more distress in people with psychosis-like experiences [Reference Schlosser, Zinberg, Loewy, Casey-Cannon, O’Brien and Bearden3] and to schizotypal personality traits in the non-clinical population [Reference Premkumar, Williams, Lythgoe, Andrew, Kuipers and Kumari4]. Schizotypy is a set of latent personality traits in the healthy population that reflect a putative risk for psychosis [Reference Fonseca-Pedrero, Debbané, Ortuño-Sierra, Chan, Cicero and Zhang5].

1.1. Schizotypy and its relationship with perceived criticism

Positive schizotypy is a dimension of schizotypal personality that constitutes spiritual beliefs, paranormal beliefs, delusions, and hallucinations [Reference Mason, Claridge and Jackson6]. It can relate to perceived criticism if criticism is socially threatening and if the social threat is attributed to spiritual and paranormal beliefs [Reference Beck7, Reference Morrison, Haddock and Tarrier8]. Perceived criticism denotes social threat, as people with social anxiety disorder are sensitive to their partner’s criticism [Reference Porter, Chambless and Keefe9]. Experiencing social threat can encourage spiritual and paranormal beliefs typical of positive schizotypy in people with certain religious beliefs in the non-clinical population [Reference Beck7, Reference Day and Peters10].

Affect plays a role in the emergence of psychosis-like experiences [Reference van Rossum, Dominguez, Lieb, Wittchen and Van Os11]. Depression related more strongly to positive schizotypy than negative schizotypy in a large college sample (n = 1,258) [Reference Lewandowski, Barrantes-Vidal, Nelson-Gray, Clancy, Kepley and Kwapil12]. Depression relates to perceived criticism in people with positive schizotypy within the non-clinical population [Reference Premkumar, Williams, Lythgoe, Andrew, Kuipers and Kumari4]. Depression could relate to perceived criticism because it increases maladaptive metacognitive beliefs about social threat, such as the person believing that criticism is uncontrollable and dangerous, and believing that one needs to worry to gain control over a situation [Reference Debbané, Van der Linden, Gex-Fabry and Eliez13, Reference Nordahl, Nordahl, Vogel and Wells14]. The relationship between depression and perceived criticism deepens if adolescents with depression find their parents irritable [Reference Hale, Raaijmakers, Hoof and Meeus15].

1.2. Schizotypy and its relationship with perceived praise

Another explanation for the relation between high EE and psychosis-like experiences is a decrement in praise. Young children who access mental health services are three times less likely to be praised than criticised by their parents [Reference Swenson, Ho, Budhathoki, Belcher, Tucker and Miller16]. Cognitive disorganisation is a schizotypal trait characterised by social anxiety, moodiness, difficulty maintaining attention, and difficulty making decisions [Reference Mason, Claridge and Jackson6]. In people in the non-clinical population with schizotypal traits, greater disorganisation relates to greater acceptance of unfair social rewards, indicating that schizotypy is associated with poor evaluation of social reward [Reference van’ T Wout and Sanfey17]. Cognitive disorganisation could relate to less perceived praise if patients with psychosis and cognitive disorganisation are less self-compassionate [Reference Gumley and Macbeth18]. Thought disorder relates to a lower need among patients with schizophrenia for others’ approval, and a poor clarity of expression from their mothers [Reference Grant and Beck19, Reference Tompson, Asarnow, Hamilton, Newell and Goldstein20]. Thought disorder is a severe form of cognitive disorganisation, characterised by illogical thinking, loose association, and peculiar language [Reference Coleman, Levy, Lenzenweger and Holzman21, Reference Loas, Dimassi, Monestes and Yon22]. A carer expressing more praise reduces disorganisation in adolescents who are at risk for psychosis [Reference O’Brien, Zinberg, Ho, Rudd, Kopelowicz and Daley23].

In contrast, excessive warmth from a close relative due to EOI relates to more anxiety across the psychosis continuum [Reference Butzlaff and Hooley24–Reference Kuipers, Bebbington, Dunn, Fowler, Freeman and Watson26]. EOI consists of parents being overprotective, intrusive, and controlling [Reference Leff, Vaughn, Leff and Vaughn1]. EOI could inhibit the child’s autonomy and competence [Reference Gurland and Grolnick27], and diminish the child’s ability to describe their emotions, such as perceiving praise [Reference Thorberg, Young, Sullivan and Lyvers28]. Meanwhile, positive affect could improve perceived praise, because positive mood broadens one’s attention and encourages positive thoughts about engaging in pleasurable social activities [Reference Fredrickson and Branigan29]. Maternal praise deepens positive mood [Reference Cuellar and Johnson30].

1.3. Study aims and hypotheses

High levels of EE in carers can relate to poor outcomes in patients with psychosis [Reference Bebbington and Kuipers2] and influence the propensity for schizotypal experiences in the healthy population [Reference Premkumar, Williams, Lythgoe, Andrew, Kuipers and Kumari4]. According to the stress diathesis hypothesis of schizophrenia [Reference Nuechterlein and Dawson31], stressors, such as persistent social environmental stress, interact with a pre-existing vulnerability for psychosis and lead to psychotic episodes. The current study aimed to determine whether affect and perceived EE could explain the relationship of schizotypy to perceived criticism and perceived praise in the general population, because EE could be perceived as threatening even in the normal range of the psychosis continuum, and so increase vulnerability for psychosis. It was hypothesised that (1) greater perceived criticism would relate to greater positive schizotypy, (2) greater perceived praise would relate to lower cognitive disorganisation, (3) depression and perceived EE would mediate the relationship between perceived criticism and positive schizotypy, and (4) positive mood and perceived EE would mediate the relationship between perceived praise and cognitive disorganisation.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Ninety-eight participants completed the study. The participants were University psychology students (90%) recruited in exchange for psychology research credits, and people from the wider public recruited through opportunistic sampling. The participants needed to have a close relative, that is a parent, sibling, or partner, with whom they were in contact for at least 10 h a week, either face-to-face or by speaking to them on the phone. This criterion was applied so that participants could perform the task of evaluating standard criticism and standard praise by referring to their close relative. Participants below 18 years and above 50 years were excluded, so that the sample represented people in early- to mid-adulthood. The participants were 22.6 years old on average (S.D. = 5.69, range 18 to 46 years, 82% were 25 years or below) and predominantly female (81%). Eighty percent of participants was single, 15% was cohabiting, and 5% was married. In terms of ethnicity, 68% was Caucasian, 24% was Asian, and 8% was of African-Caribbean heritage.

2.2. Psychometric assessments

2.2.1. Oxford-Liverpool inventory of feelings and experiences (O-LIFE) [Reference Mason, Claridge and Jackson6]

The participants rated the 104 O-LIFE items on a 2-point scale (Yes/No). The scale has four subscales, namely unusual experiences (positive schizotypy), cognitive disorganisation (social anxiety, moodiness, and lack of concentration), introvertive anhedonia (withdrawal and lack of pleasure in physical and social sources), and impulsive non-conformity (aggression and lack of self-control). Impulsive non-conformity is less relevant to the schizotypal organisation compared to other subscales [Reference Mason32], and so was not included in subsequent analyses. The subscales have good internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha, α) in the current sample: unusual experiencesα = 0.89, cognitive disorganisationα = 0.89, introvertive anhedoniaα = 0.78, impulsive non-conformityα = 0.70.

2.2.2. Depression, anxiety, and stress scale (short form, DASS-21) [Reference Lovibond and Lovibond33]

The scale has 21 items of which 7 items measured depression and 7 measured anxiety. Participants rated the items by referring to their past week. The items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale. The subscales have good internal reliability in the current sample (α = 0.86).

2.2.3. Level of expressed emotion scale (LEE) [Reference Cole and Kazarian34, Reference Gerlsma and Hale35]

The 38-item version of the LEE scale measures a person’s perception of EE in their close relative over the last three months. The scale measures lack of emotional support, intrusiveness, irritability, and criticism. The participants rated the items on a 4-point Likert scale. The subscales have good to excellent internal reliability in the current sample as follows, lack of emotional supportα = 0.93, intrusivenessα = 0.82, irritabilityα = 0.80, and criticismα = 0.75.

2.2.4. Perceived criticism scale [Reference Hooley and Teasdale36]

This is a single-item question. It asks the individual, ‘How critical is your spouse/relative of you?’ It is rated on a 10-point Likert scale [Reference Hooley and Teasdale36]. A higher rating of perceived criticism relates to more EE-criticism from a carer in patients with psychosis; however, the measure is less predictive of patient psychopathology than directly rated EE-criticism [Reference Docherty, St-Hilaire, Aakre, Seghers, McCleery and Divilbiss37, Reference Onwumere, Kuipers, Bebbington, Dunn, Freeman and Fowler38].

2.2.5. Positive and negative affect scale (PANAS) [Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen39]

This scale has 10 positive mood descriptors denoting a state of high energy, full concentration, and pleasurable engagement, and 10 negative mood descriptors denoting aversive mood. Participants indicated how much they currently felt about each descriptor on a 5-point Likert scale. The internal reliability of positive moodα was 0.91, and that of negative moodα was 0.86 in the current sample.

2.3. Affective evaluation of standard criticism and standard praise

The participants listened to 40 standard criticisms, 40 standard praises, and 40 standard neutral comments, and evaluated the arousal and personal relevance of the comments by referring to their close relative. These comments had been developed in an earlier study [Reference Premkumar, Dunn, Kumari, Onwumere and Kuipers40]. The criticisms followed the conventions of rating the Camberwell Family Interview of a close relative (the gold standard measure for rating EE) for EE-criticism which is defined as ‘a statement which, by the manner in which it is expressed, constitutes an unfavourable comment upon the behaviour or personality of the person to whom it refers’ [Reference Leff, Vaughn, Leff and Vaughn1, p. 38]. Likewise, praise was developed following the conventions of rating the Camberwell Family Interview for EE-positive comments which is defined as a statement that expresses ‘praise, approval or appreciation of the behaviour or personality of the person to whom it refers’ [Reference Leff, Vaughn, Leff and Vaughn1, p. 62–63]. Neutral comments were scientific facts and comments on the weather. Comments were spoken in a male or female voice. The speakers were postgraduate Psychology students who had a similar age and level of education. The speakers were trained to emphasise different emotional reactions in their tone and pitch just as when a close relative evokes criticism and positive comments. Criticism lasted longer when spoken in a female voice [mean (S.D.) = 8.2 s (0.72)] than a male voice [mean (S.D.) = 6.1 s (0.44)], F (1, 38) = 456.5, p < 0.001. Praise lasted longer when spoken in a female voice [mean (S.D.) = 6.8 s (1.3)] than a male voice [mean (S.D.) = 6.4 s (0.80)], F (1, 38) = 3.9, p = 0.05. Neutral comments lasted longer when spoken in a female voice [mean (S.D.) = 9.7 s (1.2)] than a male voice [mean (S.D.) = 7.9 s (1.0)], F (1, 38) = 244.7, p = 0.05.

2.4. Procedure

Participants were administered the task individually in a Psychology research lab. The participants rated their current mood before performing the evaluation task. Participants were told that they would listen to auditory remarks comprising criticisms, praise, and neutral comments. The emotional comments would be the kind of comments the participant would hear day-to-day in conversation with their close relative. On listening to each comment, participants were asked to answer how arousing (i.e. emotionally demanding) the comment was, and how relevant the comment was in terms of their own close relationships. Then, they listened to the comments through a pair of headphones (Sennheiser HD-205) and scored them on arousal (‘How arousing was this comment?’) and personal relevance (‘How relevant was this comment?’) on 11-point Likert scales. The task was delivered on a computer using Opensesame (version 0.27.2) [Reference Mathôt, Schreij and Theeuwes41]. The task took approximately 20 min. At the end, participants completed an online survey (Google forms) containing the abovementioned scales. The study received ethical approval from the University’s School of Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (No. 2013/27).

2.5. Statistical analysis

The median arousal and median relevance of the 40 comments in each condition (criticism, praise, and neutral comments) were calculated. Analyses of variance compared the three conditions on the median arousal and median relevance of the comments. Two-tailed Pearson correlations were performed between the evaluations of criticism and praise (median arousal and median relevance) on the one hand, and scores of schizotypy, depression, anxiety, positive mood, and negative mood, Perceived Criticism Scale, and LEE, on the other hand. A mediation analysis was performed with relevance of criticism as the predictor variable, positive schizotypy (O-LIFE unusual experiences) as the outcome variable, and LEE-irritability and depression as the mediators. Five thousand bootstrap samples were applied. A second mediation analysis was performed with the relevance of praise as the predictor variable, cognitive disorganisation as the outcome variable, and LEE-intrusiveness and positive mood as mediators. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS (version 24) and the PROCESS macro in SPSS [Reference Hayes42].

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

Twelve participants (12%) had high positive schizotypy based on a score ≥18 on the O-LIFE unusual experiences subscale [Reference Mason, Claridge and Jackson43]. Seventy-one percent of the sample had normal to mild depression, 15% had moderate depression and 14% had severe depression [Reference Lovibond and Lovibond33]. Fifty-three percent had normal to mild anxiety, 19% had moderate anxiety and 28% had severe anxiety.

3.2. Evaluations of criticism and praise

There was a main effect of emotion on arousal, F (1.78, 173.14) = 281.59, p < 0.001 (the Greenhouse-Geisser method of correcting the violation of the sphericity assumption was applied). Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests showed that praise was more arousing than criticism [mean difference (standard error of mean, S.E.M.) = 1.03 (0.26), p < 0.001], and more arousing than neutral comments [mean difference (S.E.M.) = 5.66 (0.21), p < 0.001]. Criticism was more arousing than neutral comments [mean difference (S.E.M.) = 4.63 (0.29), p < 0.001].

There was a main effect of emotion on relevance, F (1.74, 168.82) = 216.08, p < 0.001. Praise was more relevant than criticism [mean difference (S.E.M.) = 1.00 (0.29), p < 0.001], and more arousing than neutral comments [mean difference (S.E.M.) = 5.06 (0.20), p < 0.001]. Criticism was more relevant than neutral comments [mean difference (S.E.M.) = 4.06 (0.27), p < 0.001].

3.3. Correlation of evaluation of criticism and praise against schizotypy, perceived EE and mood

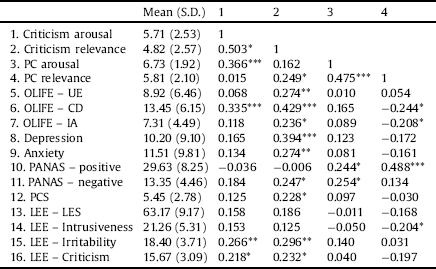

The relevance of criticism correlated positively with several schizotypal subscales, namely unusual experiences (positive schizotypy), cognitive disorganisation, and introvertive anhedonia, and with depression, negative mood, perceived criticism LEE-irritability, and LEE-criticism. The arousal from criticism correlated positively with cognitive disorganisation, LEE-irritability, and LEE-criticism (Table 1). The relevance of praise correlated negatively with the schizotypal traits of cognitive disorganisation and introvertive anhedonia, and LEE-intrusiveness, and positively with positive mood. The arousal from praise correlated positively with positive mood and negative mood.

Table 1 Mean (standard deviation) and zero-order correlations between arousal and relevance of criticism and praise, and schizotypy, depression, perceived criticism, level of expressed emotion, and mood.

3.4. Mediators of the relationship between schizotypy and the relevance of criticism and praise

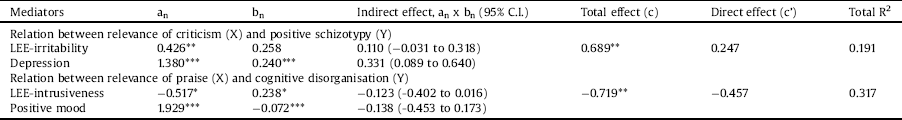

The first mediation analysis revealed that the relevance of criticism had a significant total effect on positive schizotypy (without the mediators, Table 2). After including the mediators (depression and LEE-irritability), the direct effect of relevance of criticism on positive schizotypy was non-significant. Fig. 1 shows that the relation between the relevance of criticism and positive schizotypy was strongest when either depression or LEE-irritability were high (‘moderate mediators’, 5% variance explained), but less so when both depression and LEE-irritability were high (‘high mediators’, 1% variance explained) and both depression and LEE-irritability were low (‘low mediators’, 0.3% variance explained). Independently, depression had a significant indirect effect on positive schizotypy, because the upper and lower limits of the 95% confidence intervals (C.I.s) had a positive value. LEE-irritability did not have an indirect effect on positive schizotypy. The overall model explained 19% of the variance in relevance of criticism.

Table 2 Mediation of the relation between relevance of criticism (X) and positive schizotypy (Y) by level of expressed emotion (LEE) – irritability and depression, and the mediation of the relation between relevance of praise (X) and cognitive disorganisation (Y) by level of expressed emotion (LEE) – intrusiveness and positive mood.

Fig. 1. Scatterplot of personal relevance of criticism against Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences (O-LIFE) unusual experiences subscale, classified by depression and perceived irritability from a close relative. Participants were classified as high mediators (black diamonds and broken and dotted black regression line) if they scored high on both depression (≥22) and perceived level of expressed emotion – irritability (≥11.5), low mediators (blue crosses and broken blue regression line) if they scored low on both depression (<22) and perceived level of expressed emotion – irritability (< 11.5), and moderate mediators (red dots and unbroken red regression line) if they scored high on either depression or perceived level of expressed emotion – irritability (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.).

Fig. 2. Scatterplot of personal relevance of praise against Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences (O-LIFE) cognitive disorganisation subscale, classified by positive mood and perceived intrusiveness from a close relative. Participants were classified as high mediators if they either scored high on perceived level of expressed emotion (EE) – intrusiveness (≥18) or low on Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale – positive mood (<12, red dots and unbroken red regression line), and low mediators if they scored low on perceived level of EE – intrusiveness (< 18) and high Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale – positive mood (≥ 12, blue crosses and broken blue regression line) (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.).

The second mediation analysis revealed that the personal relevance of praise had a significant total effect on cognitive disorganisation (Table 2). After including the mediators (LEE-intrusiveness and positive mood), the direct effect of the personal relevance of praise on cognitive disorganisation was non-significant. Fig. 2 shows that the relation between the personal relevance of praise and cognitive disorganisation was stronger when LEE-intrusiveness was high (‘high mediators’, 7% variance explained), but positive mood was low, rather than when LEE-intrusiveness was low, but positive mood was high (‘low mediators’, 3% variance explained). Independently, neither LEE-intrusiveness nor positive mood had indirect effects on the relationship between personal relevance of praise and cognitive disorganisation. The overall model explained 31% of the variance in personal relevance of praise.

4. Discussion

High EE is a part of the stress diathesis of schizophrenia. This study tested the differences in the affective response to standard criticism and standard praise, and the relation of schizotypy to perceived criticism and perceived praise in the non-clinical population. Participants differentiated between the comments, such that praise was more arousing and relevant than criticism, which in turn was more arousing and relevant than neutral comments. The findings suggest that in a non-clinical sample, people have a preference for praise over criticism. In many affective paradigms, healthy participants show a preference for positive emotional stimuli [Reference Clark, Milberg and Erber44]. As hypothesised, the greater personal relevance of criticism related to greater positive schizotypy and the lesser personal relevance of praise related to greater cognitive disorganisation. These findings are discussed below.

4.1. Relationship between perceived criticism and schizotypy

Perceived criticism related to all schizotypy subscales, namely positive schizotypy, cognitive disorganisation, and introvertive anhedonia, which supports evidence that EE-criticism relates to a vulnerability for psychosis [Reference Schlosser, Zinberg, Loewy, Casey-Cannon, O’Brien and Bearden3] and that people at risk for psychosis find standard criticism more relevant than low-risk controls [Reference Weintraub, de Mamani, Villano, Evans, Millman, Hooley and Timpano45]. Young adults feel more paranoid after reading criticism, than warm or neutral statements [Reference Butler, Berry, Ellett and Bucci46]. Together, the findings suggest that greater criticism is perceived within the normal to sub-clinical range of the psychosis continuum, and its relation to schizotypy is multidimensional, meaning that it can follow both cognitive and affective pathways to psychosis-like experiences. These findings support the stress-diathesis model of schizophrenia [Reference Nuechterlein and Dawson31] and evidence for the affective pathway to positive symptoms of psychosis, as suggested by Garety et al. [Reference Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman and Bebbington47]. However, the findings contradict evidence that social anxiety does not relate to psychotic symptoms, such as auditory hallunications and persecutory delusions [Reference Michail and Birchwood48]. Auditory hallucinations constitute the positive dimension of psychosis-like experiences, and often reflect a close relative’s remarks, such as criticism [Reference Hayward and Fuller49]. Hallucinations and delusions could be more intense when criticism is perceived and when family conflict occurs. For instance, people with social anxiety internalise more criticism than people without social anxiety [Reference Porter, Chambless and Keefe9, Reference Vriends, Meral, Bargas-Avila, Stadler and Bögels50]. Adolescents at risk of developing psychosis can reciprocate such family conflict [Reference O’Brien, Zinberg, Ho, Rudd, Kopelowicz and Daley23, Reference Goldstein, Miklowitz, Strachan, Dozne, Nuechterlein and Feingold51], and so experience social threat. Depression and perceived irritability from a close relative fully mediated the relationship between the personal relevance of criticism and positive schizotypy, with depression mostly explaining this relationship. As posited by Garety et al. [Reference Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman and Bebbington47], affect might be the pathway to psychosis, as depression could denote having catastrophic thoughts about the threat posed by criticism. Such negative metacognitive beliefs are detrimental, and increase psychosis-like experiences [Reference Debbané, Van der Linden, Gex-Fabry and Eliez13, Reference Nordahl, Nordahl, Vogel and Wells14].

4.2. Relationship between perceived praise and cognitive disorganization

The study found a relationship between the lower personal relevance of praise and greater cognitive disorganisation in schizotypy. Praise denotes affection, approval, and the need to establish closeness [Reference Myers, Byrnes, Firsby and Mansson52]. Maternal praise could boost the child’s feelings of competence and confidence [Reference Swenson, Ho, Budhathoki, Belcher, Tucker and Miller16]. Patients with schizophrenia can have symptoms of disorganisation if they do not perceive warmth and compassion for themselves [Reference Gumley and Macbeth18]; therefore, they may not perceive praise from others. Warmth reduces the likelihood of subsequent relapse in patients with a recent onset of psychosis [Reference Lee, Barrowclough and Lobban53]. Praise from a close relative reduces disorganisation in adolescents at risk for psychosis [Reference O’Brien, Zinberg, Ho, Rudd, Kopelowicz and Daley23].

Perceived EE-intrusiveness and positive mood partially mediated the relationship between the personal relevance of praise and cognitive disorganisation. When one is excessively praised by a relative, one could perceive the relative as trying to exert control over them, and not be interested in the praise. EOI, as denoted by perceived EE-intrusiveness, could limit the individual’s autonomy and ability to perceive praise [Reference Gurland and Grolnick27], instead making them feel anxious and disorganised [Reference Jacobsen, Hibbs and Ziegenhain54]. Intrusive parenting can be manipulative through use of strategies of guilt-induction, love withdrawal, and conditional approval [Reference Barber55], which might well impede the ability to perceive praise. Positive mood could buffer the relationship between perceived praise and cognitive disorganisation. Praise enhances positive mood in people at risk for psychosis [Reference Weintraub, de Mamani, Villano, Evans, Millman, Hooley and Timpano45]. Positive mood enhances social connectedness, and satisfaction with family relationships [Reference Ramsey and Gentzler56, Reference Smillie, Wilt, Kabbani, Garratt and Revelle57], which can lower cognitive disorganisation. Having a positive mood when pursuing pleasurable activities relates to better emotional adjustment [Reference Gentler, Morey, Palmer and Yi58], which may lower cognitive disorganisation.

4.3. Limitations and implications

The study had a few limitations. The study’s sample mainly consisted of University students (90%) who were single and female. The findings may not generalise to older adults, couples, or people in non-academic settings. However, the use of psychology students in schizotypy research is not thought to adversely affect the validity of findings [Reference Kwapil, Barrantes-Vidal and Silvia59]. Yet, the participants’ current or previous diagnosis of psychiatric disorder was not known in this study. Thus, the findings may not be exclusive to non-clinical schizotypal traits. Future research might address the role of other demographic characteristics relevant to the participant’s family background, such as housing and type of family, in the relation between perceived EE and schizotypy.

The practical implications of the study are that the evaluation of standard criticism and standard praise could be used to assess the level of distress in patients with psychosis. This kind of research might also provide a theoretical basis for family intervention. Perceived EE has long-term effects on the cognition and affect of adolescents [Reference Hale, Raaijmakers, Hoof and Meeus15]. Parents of anxious young adults could be supported to modify their style of communication, i.e. speaking without excessive criticism or praise, as this would reduce the young adult’s disorganisation. Early intervention services try to help families to improve their communication through problem-solving, sharing new ideas, and reassurance of worth [Reference Barnes, Olson, Olson, McCubbin, Barnes, Larsen, Muxen and Wilson60, Reference Cutrona61], as well as helping individuals to achieve independence, appraising criticism constructively, and engaging in pleasurable social activities to increase positive mood and perceived praise [Reference Fredrickson and Branigan29].

5. Conclusion

Schizotypy relates to greater perceived criticism and praise in the healthy population due to affect and perceived irritability and intrusiveness from a close relative. These associations, if they persist, may increase the risk for psychosis. The evaluation of criticism and praise underline the ways in which the family can intervene to reduce distress. Such family intervention is recommended for those with psychosis [62, Reference Kuipers, Yesufu-Udechuku, Taylor and Kendall63].

Declaration of conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Statement of funding

The authors received no funding from an external source.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.