Early childhood feeding practices, especially in the first 2 years of life, are crucial for a healthy growth and development, shaping feeding habits that can last for a lifetime(1,Reference Black, Victora and Walker2) . A poor and unhealthy diet is associated with child malnutrition especially in low- and middle-income countries, where undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies often coexist with overweight/obesity and non-communicable diseases, a phenomenon called double burden of malnutrition(Reference Black, Victora and Walker2,Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Allender3) . Therefore, it is essential to provide reliable information about children’s diet to allow health professionals to monitor dietary changes and plan actions.

Measuring the quality of the diet remains a challenge, as there is no consensus on which attributes should be included in this assessment, and an agreement does not exist about the most appropriate concept of what is a globally healthy and diverse diet(Reference Alkerwi4,Reference Gil5,Reference Bhutta, Das and Rizvi6,7,Reference Daelmans, Dewey and Arimond8) . According to Alkerwi (2014), when evaluating a diet, protocols should be adopted that combine several characteristics of the diet, so that the overall quality of the diet can be measured more reliably(Reference Alkerwi4). Ideally, in addition to nutritional aspects, other points should be part of this diet assessment, such as food security, sensory properties of food, and socio-cultural factors, which also still lack established measurement parameters.

Several approaches have been used to assess children’s diets worldwide, and the use of indexes for assessing the overall diet quality has gained prominence. This is an a priori approach, which consists of assessing dietary intake data against a pre-established index according to a theoretical framework, generally based on current dietary recommendations(Reference Smithers, Golley and Brazionis9). According to Ruel and Menon (2002)(Reference Ruel and Menon10), one of the main advantages of creating indexes is that they can be age-specific and can include different dimensions of eating practices, combining the information in a summary measure. In addition, indexes can be easier to interpret than a set of individual indicators and allow comparison of complex dimensions. However, failures in the construction and interpretation of the index can cause miscommunication and problems in decision-making(11).

Several systematic reviews on global diet quality indexes for the adult population have been published in the last 20 years(Reference Gil5,Reference Kant12–Reference Asghari, Mirmiran and Yuzbashian16) . But only four systematic reviews were found that identified indexes used to assess the diet of children under 2 years old; however, they included older children and adolescents, included indexes focused on specific aspects of the diet or specific health conditions, or included a posteriori dietary assessment method. In addition, in the most recent review, the search was conducted in only two databases, selecting articles published until 2013(Reference Smithers, Golley and Brazionis9,Reference Lazarou and Newby17–Reference Marshall, Burrows and Collins19) ; thus, the present study fills a relevant gap in the literature.

Considering the scarcity of literature on this theme, the objective of this study was to systematically review studies that developed and/or applied original and adapted indexes to assess eating practices and the overall dietary quality of children under 2 years old. We also aimed to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the identified indexes.

Methods

The systematic review protocol was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42019119153) and was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses 2015 framework (PRISMA-P)(Reference Moher and Shamseer20).

Databases and keywords

The scientific databases MEDLINE via PubMed, Scopus, Embase, Scielo, Lilacs, Cochrane and ProQuest (for grey literature) were searched with no limit set for date and language. The following search strategy was built for PubMed database and adapted to the other databases: (Infant OR Child, Preschool OR Infant, Newborn) AND (Nutrition Surveys OR Diet Surveys OR Food variety score OR Dietary diversity score OR Diet score OR Healthy eating index OR Child feeding index OR Complementary feeding indicators OR Infant feeding index) AND (Infant Nutrition OR Nutritional Status OR Feeding Behavior OR Breast Feeding OR Bottle Feeding OR Mixed Feeding OR Young child feeding practices OR Complementary feeding OR Feeding practice OR Complementary foods OR Assessing Foods OR Dietary habits OR Diet quality OR Food intake). The search strategy employed a wide range of keywords to recover the largest number of studies in the field. The initial search was conducted in November 2019. Then, the search was updated in July 2020 using the same strategy and databases, with the application of a publication date filter (2019–2020).

Eligibility criteria

In this study, an index – which can also be called a composite indicator – is understood as a summary measure, built from the aggregation of multiple components, supported by a base model(11). We included studies with full text available, of all types of quantitative designs, which may be original articles, dissertations, theses and official documents from national and international organizations, which used at least one index developed for the assessment of dietary practices of children under 2 years old. Exclusion criteria were studies that used a posteriori methods to assess dietary patterns, studies that focused only on breast-feeding (BF) assessment; studies that individually evaluated specific attributes of feeding practices without using an index; studies whose objective was to assess behaviours, knowledge or practices of parents or caregivers and studies with unhealthy populations. Systematic reviews, books, editorials and conference abstracts were also excluded.

Procedures and synthesis

Studies were first screened by title and abstract by two reviewers (R1 and R2). The second step was the full reading of selected publications independently by reviewers R1 and R2 to identify those that met all the inclusion criteria and would remain in the review. Disagreements were discussed between reviewers R1 and R2, and if there was no consensus, the reviewers R3 and R4 were consulted. The third step was to identify studies that presented: (a) original indexes; (b) modified indexes and (c) studies that only used indexes previously published, without changes. Adapted indexes were considered those that maintained the main characteristics of the original index and clearly described the changes made; articles that did not present the modifications objectively were not included.

Only the first and second groups of articles (original and modified indexes) were included in the data extraction and synthesis presented in this systematic review. The search and selection of articles were performed using the StArt software (State of the Art through Systematic Review)(21).

The first reviewer extracted the data, and the second reviewer checked it for completion and accuracy. Data were extracted in a table designed specifically for this study (see online Supplemental Material S1a and S1b), including study information (title, author, year of publication, country, funding, design), sample characteristics (age, sample size and inclusion/exclusion criteria) and characteristics of the indexes – description, dietary components, dietary assessment methods, food groups (if applicable), index scoring system, key findings of studies, strengths and limitations of the index indicated by the authors themselves and measures related to the validation process (if available in the study). Data synthesis is presented in Tables 1, 2, and 3.

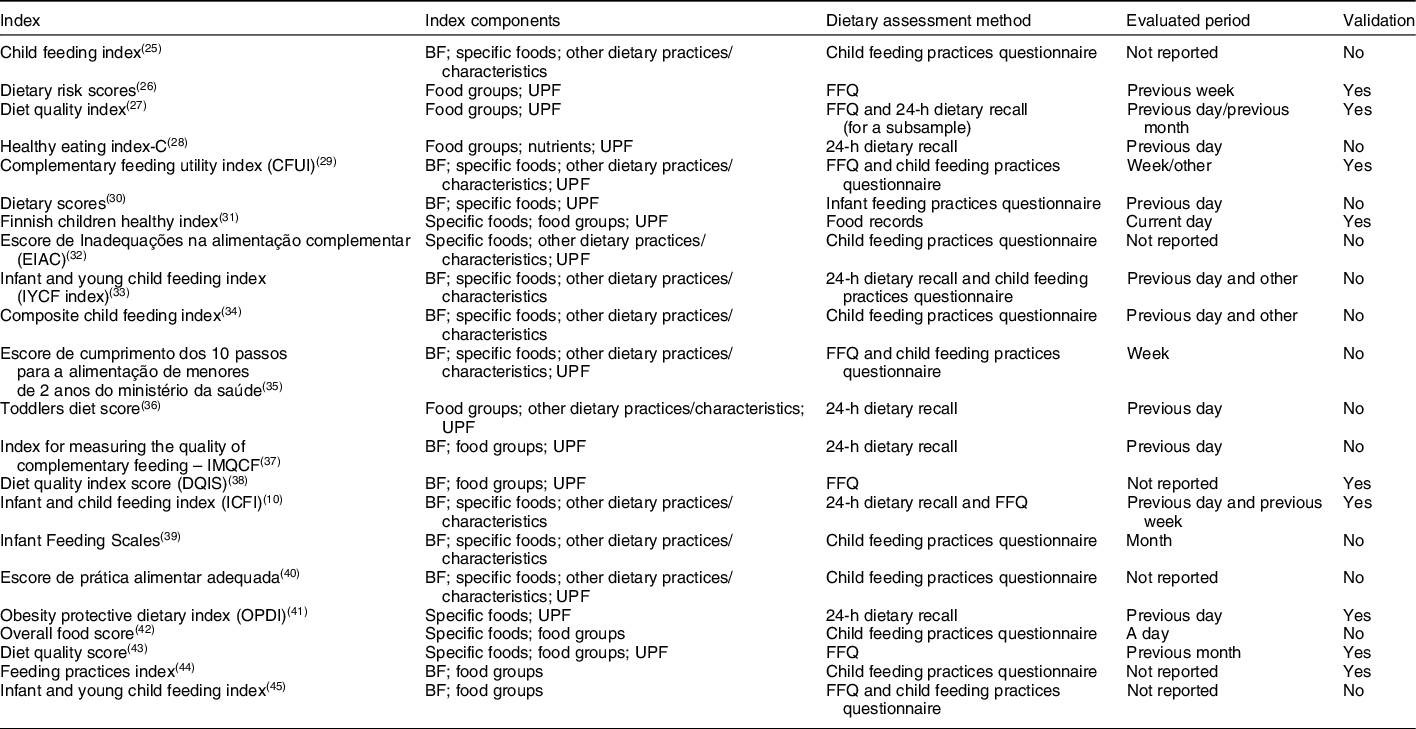

Table 1 Characteristics of original indexes used for assessment of infant and young child feeding practices

BF, breast-feeding; UPF, ultra-processed foods; FFQ, Food Frequency Questionnaire.

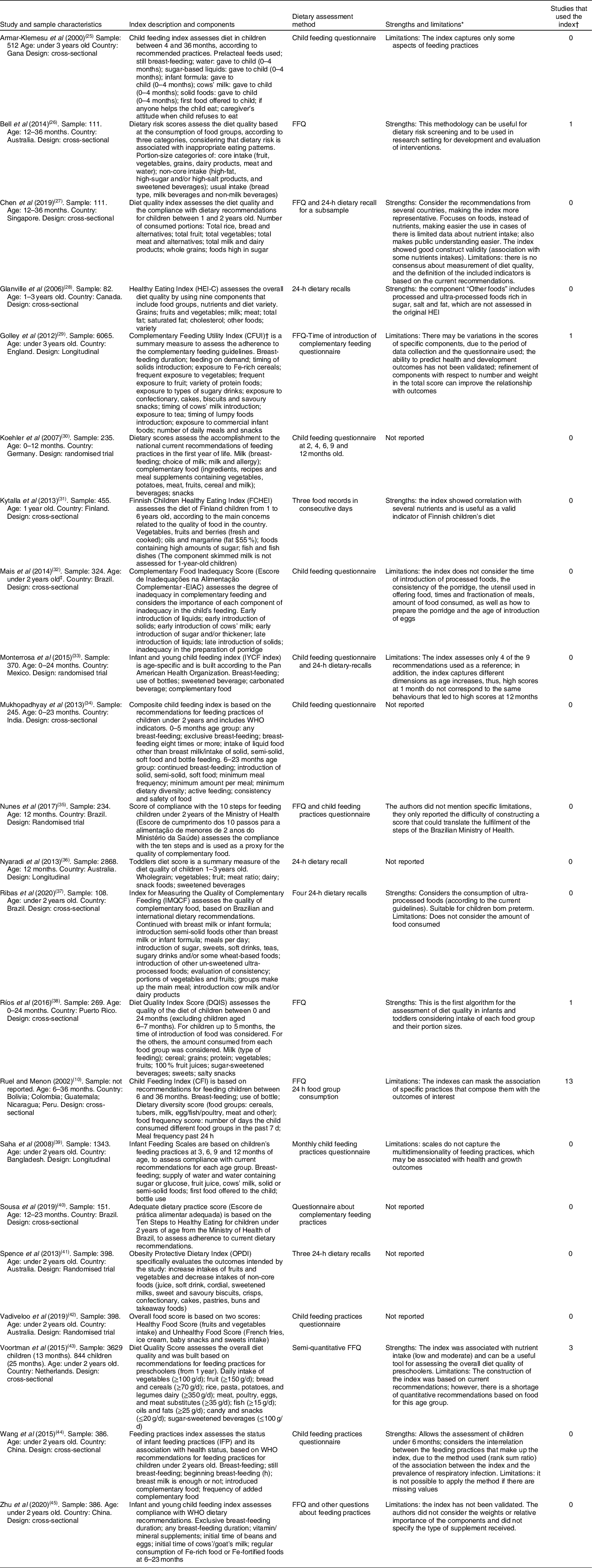

Table 2 Description of studies that used original indexes for assessment of infant and young child feeding practices

* Strengths and limitations pointed out by studies’ authors.

† Studies that used the original indexes without adaptations.

‡ The age range of the participants included in the study was 0–6 years old, but the assessment of complementary feeding practices referred to the first 2 years of age of children.

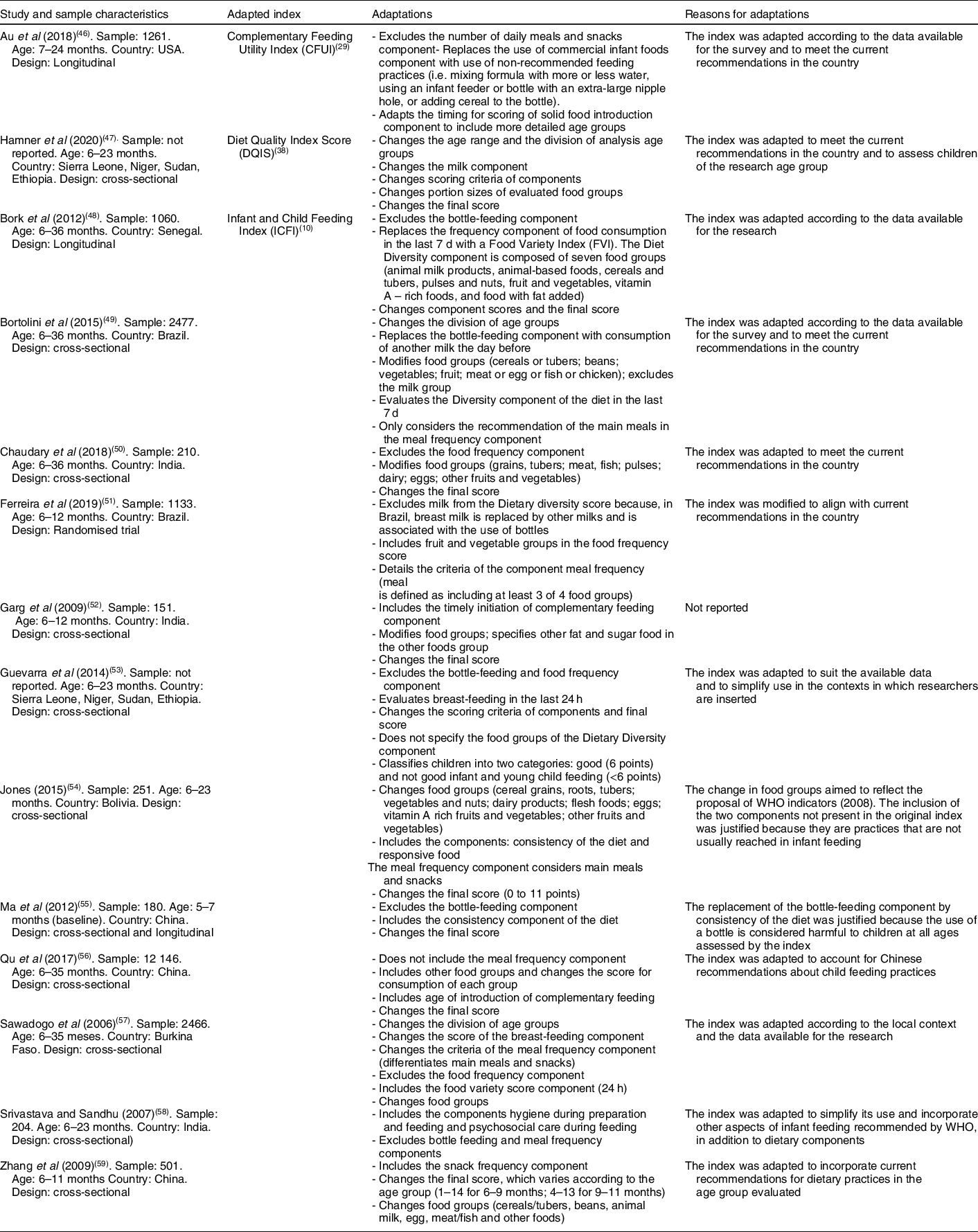

Table 3. Description of studies that used adapted indexes for assessment of infant and young child feeding practices

Risk of bias assessment

The assessment of the risk of bias in the studies was performed by R1 and checked by R2 to ensure the accuracy of the assessment (see online Supplemental material S3). To assess the quality of observational study designs, we employed the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale instrument for longitudinal studies and the adapted version for cross-sectional studies(Reference Wells, Shea and O’Connell22,Reference Modesti, Reboldi and Cappuccio23) ; this instrument classifies the quality of studies as good, fair or poor. The following modifications were made to the instruments to better suit the studies: for cross-sectional studies that used secondary data, the question about non-respondents (Selection section) was considered not applicable and the maximum section score was four stars; in that same section (Selection), for the question dealing with the exposure of the instrument, we considered whether the dietary instrument used was validated or was described in the study. In the case of longitudinal studies, question 4 of the Selection section does not apply to the included studies; thus, the maximum value of this section was three stars. For intervention studies, the quality assessment instrument for quantitative studies of the Effective Public Health Practice Project(Reference Ciliska, Miccuci and Dobbins24) was employed, which classifies studies as strong, moderate or weak. Studies with analyses of more than one type of design were evaluated for both instruments.

Results

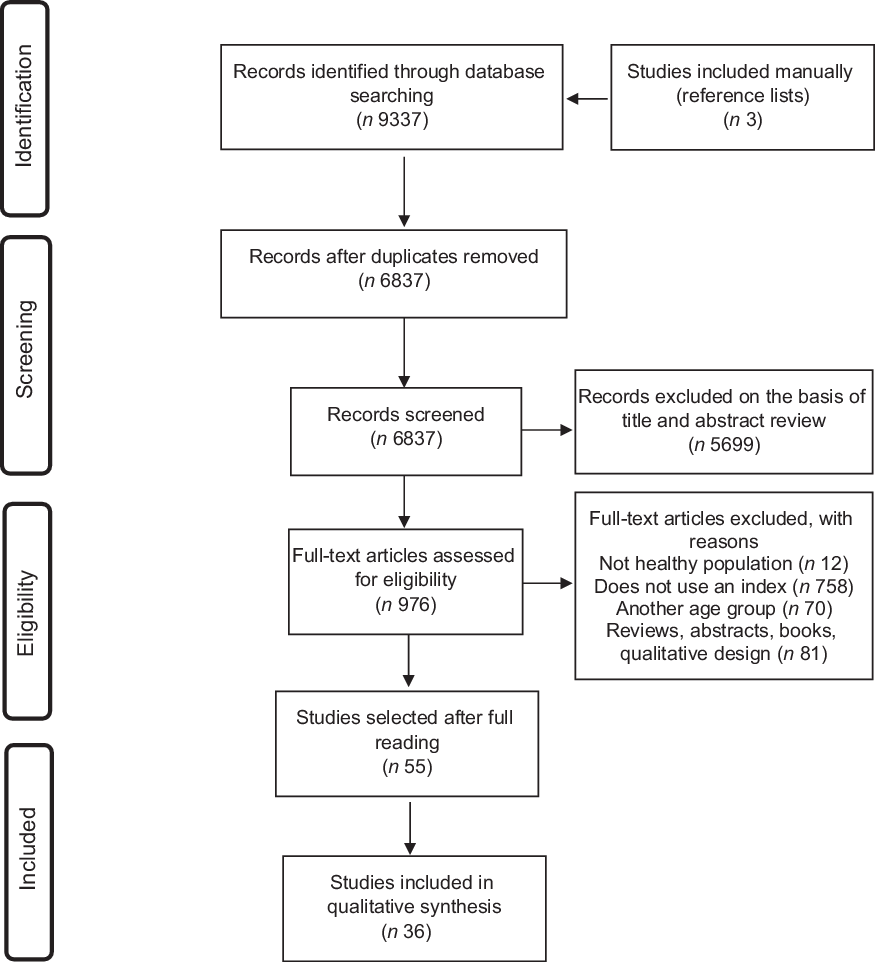

The process of identifying and selecting the articles is presented in a PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1). After removing the duplicates, 6837 publications were screened for title and abstract and 976 were selected for full reading. Most of the items (n 758) were excluded because they assessed only individual attributes of children’s diet, without using an index. After the full reading, fifty-six articles were identified that employed at least one index to assess child feeding practices. As described in the Methods section, an additional step was done to classify the selected articles into three groups: original indexes, adapted indexes and studies that only used a previously published index, without modifications. After this step, we identified thirty-six studies that presented an original or adapted index and were selected for data extraction and synthesis in this review. Of these, twenty-two described original indexes(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Armar-Klemesu, Ruel and Maxwell25–Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45) and fourteen described adapted indexes(Reference Au, Gurzo and Paolicelli46–Reference Zhang, Shi and Wang59). The other twenty articles that only used existing indexes without changes are presented in Supplementary Material S2.

Fig. 1 Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the study selection process

Overview of the studies

All indexes were constructed to assess compliance with current dietary recommendations for this age group and/or the quality of the diet in the first years of life.

The studies included in the qualitative synthesis were published between 2000 and 2020, with the majority (n 26) after 2010(Reference Bell, Golley and Magarey26,Reference Chen, Fung and Fok27,Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29,Reference Kyttälä, Erkkola and Lehtinen-Jacks31–Reference Ríos, Sinigaglia and Diaz38,Reference Sousa, Javorski and Sette40–Reference Ferreira, Sangalli and Leffa50,Reference Guevarra, Siling and Chiwile52–Reference Jones54,Reference Qu, Mi and Wang56) . Six studies were published between 2019 and 2020(Reference Chen, Fung and Fok27,Reference Ribas, de Rodrigues and Mocellin37,Reference Vadiveloo, Tovar and Østbye42,Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45,Reference Ferreira, Sangalli and Leffa50,Reference Hamner and Moore53) . The sample ranged from eighty-two(Reference Glanville and Mcintyre28) to 12 146(Reference Qu, Mi and Wang56) participants.

Twenty-four studies employed a cross-sectional design(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Armar-Klemesu, Ruel and Maxwell25–Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29,Reference Kyttälä, Erkkola and Lehtinen-Jacks31,Reference Mais, Domene and Barbosa32,Reference Mukhopadhyay, Sinhababu and Saren34,Reference Ribas, de Rodrigues and Mocellin37,Reference Ríos, Sinigaglia and Diaz38,Reference Sousa, Javorski and Sette40,Reference Voortman, Kiefte-de Jong and Geelen43,Reference Wang, Dang and Xing44,Reference Bortolini, Vitolo and Gubert48,Reference Chaudhary, Govil and Lala49,Reference Guevarra, Siling and Chiwile52–Reference Jones54,Reference Qu, Mi and Wang56–Reference Zhang, Shi and Wang59) , six were longitudinal studies(Reference Nyaradi, Li and Hickling36,Reference Saha, Frongillo and Alam39,Reference Vadiveloo, Tovar and Østbye42,Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45–Reference Bork, Cames and Barigou47) , five were intervention studies(Reference Koehler, Sichert-Hellert and Kersting30,Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo and Neufeld33,Reference Nunes, Vigo and Oliveira35,Reference Spence, McNaughton and Lioret41,Reference Ferreira, Sangalli and Leffa50) and one presented cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses(Reference Ma, Zhou and Hu55).

Twelve studies were conducted in Asian countries(Reference Chen, Fung and Fok27,Reference Mukhopadhyay, Sinhababu and Saren34,Reference Saha, Frongillo and Alam39,Reference Wang, Dang and Xing44,Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45,Reference Chaudhary, Govil and Lala49,Reference Garg and Chandha51,Reference Ma, Zhou and Hu55–Reference Zhang, Shi and Wang59) , ten in Latin America(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Mais, Domene and Barbosa32,Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo and Neufeld33,Reference Nunes, Vigo and Oliveira35,Reference Ribas, de Rodrigues and Mocellin37,Reference Ríos, Sinigaglia and Diaz38,Reference Sousa, Javorski and Sette40,Reference Bortolini, Vitolo and Gubert48,Reference Ferreira, Sangalli and Leffa50,Reference Jones54) , four studies in Europe(Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29–Reference Kyttälä, Erkkola and Lehtinen-Jacks31,Reference Voortman, Kiefte-de Jong and Geelen43) , four in North America(Reference Glanville and Mcintyre28,Reference Vadiveloo, Tovar and Østbye42,Reference Au, Gurzo and Paolicelli46,Reference Hamner and Moore53) , three in Oceania(Reference Bell, Golley and Magarey26,Reference Nyaradi, Li and Hickling36,Reference Spence, McNaughton and Lioret41) and three in Africa(Reference Armar-Klemesu, Ruel and Maxwell25,Reference Bork, Cames and Barigou47,Reference Guevarra, Siling and Chiwile52) . Only two studies(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Guevarra, Siling and Chiwile52) evaluated data from more than one country. Most studies (n 25) were conducted in low- and middle-income countries.

Risk of bias assessment

According to Newcastle–Ottawa Scale instrument, twenty-four articles were classified as having good quality (twenty cross-sectional; four longitudinal)(Reference Armar-Klemesu, Ruel and Maxwell25,Reference Chen, Fung and Fok27,Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29,Reference Kyttälä, Erkkola and Lehtinen-Jacks31,Reference Mais, Domene and Barbosa32,Reference Mukhopadhyay, Sinhababu and Saren34,Reference Ríos, Sinigaglia and Diaz38,Reference Sousa, Javorski and Sette40,Reference Vadiveloo, Tovar and Østbye42–Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45,Reference Bork, Cames and Barigou47–Reference Chaudhary, Govil and Lala49,Reference Garg and Chandha51,Reference Hamner and Moore53–Reference Zhang, Shi and Wang59) , three were allocated to the fair category(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Ribas, de Rodrigues and Mocellin37,Reference Au, Gurzo and Paolicelli46) and five as poor(Reference Bell, Golley and Magarey26,Reference Glanville and Mcintyre28,Reference Nyaradi, Li and Hickling36,Reference Saha, Frongillo and Alam39,Reference Guevarra, Siling and Chiwile52) . The main reasons why the articles were classified as fair or poor were because they did not justify the sample size, state the response rate and the characteristics of the non-respondents or control the analyses for possible confounding factors. When the Effective Public Health Practice Project instrument was used to evaluate intervention studies, four studies were classified as strong(Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo and Neufeld33,Reference Nunes, Vigo and Oliveira35,Reference Spence, McNaughton and Lioret41,Reference Ferreira, Sangalli and Leffa50) and one as moderate(Reference Koehler, Sichert-Hellert and Kersting30), due to the lack of information about blinding and the low agreement rate for participation in the study. The evaluation of the articles is described in Supplementary Material S3.

Studies with original indexes

The synthesis of the main characteristics of the original indexes (n 22) is presented in Table 1. Table 2 presents the characteristics of these studies: identification of the study, sample characteristics, index used, components, dietary assessment method, strengths and limitations of the index, and number of studies found in the systematic review which used that index.

The indexes were constructed with different types of components, which focus on assessing BF (exclusive and continued BF), consumption of foods and food groups, other feeding practices (frequency of meals, bottle use, hygiene when preparing and offering food, complementary food introduction, if the child receives help to eat, the caregiver’s attitude towards the child’s refusal, exposure to advertising about infant foods) and consistency of the diet. Among the twenty-two original indexes, thirteen evaluate aspects related to BF(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Armar-Klemesu, Ruel and Maxwell25,Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29,Reference Koehler, Sichert-Hellert and Kersting30,Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo and Neufeld33–Reference Nunes, Vigo and Oliveira35,Reference Ribas, de Rodrigues and Mocellin37–Reference Sousa, Javorski and Sette40,Reference Wang, Dang and Xing44,Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45) (more common in the indexes that assess diet of children under 1 year old), fourteen evaluate consumption of foods(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Armar-Klemesu, Ruel and Maxwell25,Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29–Reference Nunes, Vigo and Oliveira35,Reference Saha, Frongillo and Alam39–Reference Voortman, Kiefte-de Jong and Geelen43) , ten assessed food groups consumption(Reference Bell, Golley and Magarey26,Reference Chen, Fung and Fok27,Reference Kyttälä, Erkkola and Lehtinen-Jacks31,Reference Nyaradi, Li and Hickling36–Reference Ríos, Sinigaglia and Diaz38,Reference Vadiveloo, Tovar and Østbye42–Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45) and ten include the assessment of other feeding practices and feeding characteristics(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Armar-Klemesu, Ruel and Maxwell25,Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29,Reference Mais, Domene and Barbosa32–Reference Nyaradi, Li and Hickling36,Reference Saha, Frongillo and Alam39,Reference Sousa, Javorski and Sette40) , such as consistency of the diet. More than half of the original indexes (n 13) investigated the consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPF) (in some studies described as foods high in Na, sugar and fat)(Reference Bell, Golley and Magarey26,Reference Chen, Fung and Fok27,Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29–Reference Mais, Domene and Barbosa32,Reference Nunes, Vigo and Oliveira35–Reference Ríos, Sinigaglia and Diaz38,Reference Sousa, Javorski and Sette40,Reference Spence, McNaughton and Lioret41,Reference Voortman, Kiefte-de Jong and Geelen43) , twelve of which were published since 2012. Only one index assessed the intake of specific nutrients(Reference Glanville and Mcintyre28).

Although the purpose of the review was to identify indexes that aimed at the population under 2 years old, we decided not to exclude studies with indexes that exceed this limit, as long as children under 2 years old were part of the analysed age group and the index was constructed taking into account the dietary recommendations for children of this age range, including seven studies(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Armar-Klemesu, Ruel and Maxwell25,Reference Bell, Golley and Magarey26,Reference Glanville and Mcintyre28,Reference Kyttälä, Erkkola and Lehtinen-Jacks31,Reference Mais, Domene and Barbosa32,Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45) .

All indexes were constructed based on the current dietary recommendations for the age group. These recommendations included country-specific guidelines and, more commonly, the general recommendations of the WHO.

As primary tool to collect dietary data, twelve studies used specific questionnaires(Reference Armar-Klemesu, Ruel and Maxwell25,Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29,Reference Koehler, Sichert-Hellert and Kersting30,Reference Mais, Domene and Barbosa32–Reference Nunes, Vigo and Oliveira35,Reference Saha, Frongillo and Alam39,Reference Sousa, Javorski and Sette40,Reference Vadiveloo, Tovar and Østbye42,Reference Wang, Dang and Xing44,Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45) containing questions related to food consumption and other aspects of eating practices, but many of them did not provide details on the instruments. Eight studies used the FFQ(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Bell, Golley and Magarey26, Reference Chen, Fung and Fok27,Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29,Reference Nunes, Vigo and Oliveira35,Reference Ríos, Sinigaglia and Diaz38,Reference Voortman, Kiefte-de Jong and Geelen43,Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45) , seven used the 24-h dietary recall(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Chen, Fung and Fok27,Reference Glanville and Mcintyre28,Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo and Neufeld33,Reference Nyaradi, Li and Hickling36,Reference Ribas, de Rodrigues and Mocellin37,Reference Spence, McNaughton and Lioret41) , one used 1-d food records(Reference Kyttälä, Erkkola and Lehtinen-Jacks31) and six studies used more than one dietary instrument(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Chen, Fung and Fok27,Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29,Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo and Neufeld33,Reference Nunes, Vigo and Oliveira35,Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45) .

About the reference time of the used tools to evaluate diet, eight studies requested dietary data from the day before the survey(Reference Chen, Fung and Fok27,Reference Glanville and Mcintyre28,Reference Koehler, Sichert-Hellert and Kersting30,Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo and Neufeld33,Reference Mukhopadhyay, Sinhababu and Saren34,Reference Nyaradi, Li and Hickling36,Reference Ribas, de Rodrigues and Mocellin37,Reference Spence, McNaughton and Lioret41) , four from the previous week(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Bell, Golley and Magarey26,Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29,Reference Nunes, Vigo and Oliveira35) , six studies did not specify the time period(Reference Armar-Klemesu, Ruel and Maxwell25,Reference Mais, Domene and Barbosa32,Reference Ríos, Sinigaglia and Diaz38,Reference Sousa, Javorski and Sette40,Reference Wang, Dang and Xing44,Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45) and the others evaluated random periods of time, such as month or year.

Regarding the quantity of food consumed, thirteen indexes assessed whether the child consumed a food/food group or not, irrespective of the quantity or number of portions(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Armar-Klemesu, Ruel and Maxwell25,Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29,Reference Koehler, Sichert-Hellert and Kersting30,Reference Mais, Domene and Barbosa32–Reference Nunes, Vigo and Oliveira35,Reference Saha, Frongillo and Alam39,Reference Sousa, Javorski and Sette40,Reference Vadiveloo, Tovar and Østbye42,Reference Wang, Dang and Xing44,Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45) . The others establish the minimum amount of food consumed or the number of portions of each food/food group, according to the dietary recommendations(Reference Bell, Golley and Magarey26–Reference Glanville and Mcintyre28,Reference Kyttälä, Erkkola and Lehtinen-Jacks31,Reference Nyaradi, Li and Hickling36–Reference Ríos, Sinigaglia and Diaz38,Reference Spence, McNaughton and Lioret41,Reference Voortman, Kiefte-de Jong and Geelen43) .

Regarding the scoring system, for most indexes, the final score was calculated by simply adding together the scores of all the components(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Armar-Klemesu, Ruel and Maxwell25,Reference Glanville and Mcintyre28,Reference Kyttälä, Erkkola and Lehtinen-Jacks31–Reference Nyaradi, Li and Hickling36,Reference Ríos, Sinigaglia and Diaz38–Reference Voortman, Kiefte-de Jong and Geelen43,Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45) . Usually, practices considered positive or recommended received positive scores and practices considered negative received negative scores or were not scored, and the final score represented the degree of compliance with the dietary recommendations for age or quality of diet; thus, higher scores indicated a greater degree of adequacy or better quality of the diet. Due to variations in dietary recommendations according to the child’s age, the indexes commonly divided the assessment by age subgroups, changing the scoring criteria or the cut-off point value according to the recommendations. An example of this variation is the assessment of BF, which usually received higher scores in the youngest subgroup. Some indexes required more complex procedures to generate the final score, such as using equations or converting scales (n 6)(Reference Bell, Golley and Magarey26,Reference Chen, Fung and Fok27,Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29,Reference Koehler, Sichert-Hellert and Kersting30,Reference Ribas, de Rodrigues and Mocellin37,Reference Wang, Dang and Xing44) .

The final results of the indexes were presented as the score mean – and sd – for the full sample or age subgroups (n 9)(Reference Armar-Klemesu, Ruel and Maxwell25,Reference Chen, Fung and Fok27,Reference Koehler, Sichert-Hellert and Kersting30,Reference Mukhopadhyay, Sinhababu and Saren34–Reference Ribas, de Rodrigues and Mocellin37,Reference Saha, Frongillo and Alam39,Reference Voortman, Kiefte-de Jong and Geelen43) , in predefined categories (e.g. total score – 0–100, ≤50: poor diet; 51–80: diet needs improvement; >80: good diet) (n 8)(Reference Bell, Golley and Magarey26,Reference Glanville and Mcintyre28,Reference Koehler, Sichert-Hellert and Kersting30,Reference Ríos, Sinigaglia and Diaz38,Reference Spence, McNaughton and Lioret41,Reference Voortman, Kiefte-de Jong and Geelen43) or classifying the final score in quantiles (n 5)(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29,Reference Kyttälä, Erkkola and Lehtinen-Jacks31,Reference Spence, McNaughton and Lioret41,Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45) .

No study compared the index to a gold reference standard for assessing food consumption for validation. Among the twenty-two original indexes identified, only five assessed the association between the results and the intake or adequacy of nutrients and energy(Reference Chen, Fung and Fok27,Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29,Reference Kyttälä, Erkkola and Lehtinen-Jacks31,Reference Spence, McNaughton and Lioret41,Reference Voortman, Kiefte-de Jong and Geelen43) . Seven studies associated the index with nutritional status(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo and Neufeld33,Reference Mukhopadhyay, Sinhababu and Saren34,Reference Ribas, de Rodrigues and Mocellin37–Reference Saha, Frongillo and Alam39,Reference Vadiveloo, Tovar and Østbye42) .

The most employed index was the ICFI proposed by Ruel and Menon (2002)(Reference Ruel and Menon10), with twelve records. Other four indexes – Dietary risk scores(Reference Bell, Golley and Magarey26), Complementary Feeding Utility Index(Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29), Diet Quality Index Score(Reference Ríos, Sinigaglia and Diaz38), Diet Quality Score(Reference Voortman, Kiefte-de Jong and Geelen43) – were also used in further studies. The full list of the studies that used original indexes is in Supplementary Material S2.

Only sixteen studies indicated strengths and/or weakness of the index used(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Armar-Klemesu, Ruel and Maxwell25–Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29,Reference Kyttälä, Erkkola and Lehtinen-Jacks31–Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo and Neufeld33,Reference Nunes, Vigo and Oliveira35,Reference Ribas, de Rodrigues and Mocellin37–Reference Saha, Frongillo and Alam39,Reference Voortman, Kiefte-de Jong and Geelen43–Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45) . The following strengths were cited: the use of the index as a valid approach for assessing and monitoring children’s eating practices, especially due to the positive association between the results of the indexes with nutrient intake and/or nutritional status; and the assessment of consumption of UPF. The most common weaknesses were the lack of consensus on the choice of components, the lack of established criteria for defining the weight and cut-off points of the components and the impossibility of including other aspects of eating practices.

Studies with adapted indexes

The fourteen studies that adapted previously published indexes are described in Table 3. The changes made to the original indexes and the justifications presented by the authors are also presented. Among these fourteen studies, twelve(Reference Bork, Cames and Barigou47–Reference Hamner and Moore53,Reference Ma, Zhou and Hu55–Reference Zhang, Shi and Wang59) were based on the Infant and Child Feeding Index by Ruel and Menon (2002)(Reference Ruel and Menon10); one(Reference Au, Gurzo and Paolicelli46) was based on the Complementary Feeding Utility Index by Golley et al (2018)(Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29) and one(Reference Hamner and Moore53) was based on the Diet Quality Index Score by Ríos et al (2020)(Reference Ríos, Sinigaglia and Diaz38).

The extent of modifications made to the original indexes varied widely between studies and included changes in the component scoring criteria; alterations in the final score; exclusion, inclusion and replacement of components; modification of evaluated food groups and adjustments in the age group, as shown in Table 3. The existing indexes were adapted for a variety of reasons: to fit the index to the data available in the research, especially studies with secondary data (n 5)(Reference Au, Gurzo and Paolicelli46–Reference Bortolini, Vitolo and Gubert48,Reference Guevarra, Siling and Chiwile52,Reference Sawadogo, Martin-Prével and Savy57) ; to adapt the indexes to the national or international current nutritional recommendations, as well as to adapt to the local food context (n 10)(Reference Au, Gurzo and Paolicelli46,Reference Bortolini, Vitolo and Gubert48–Reference Ferreira, Sangalli and Leffa50,Reference Hamner and Moore53–Reference Ma, Zhou and Hu55,Reference Sawadogo, Martin-Prével and Savy57–Reference Zhang, Shi and Wang59) ; or to aggregate components not evaluated in the original indexes that were considered important by the authors (n 1)(Reference Jones54). One study reported no justification for the changes(Reference Garg and Chandha51).

Two adapted indexes(Reference Guevarra, Siling and Chiwile52,Reference Sawadogo, Martin-Prével and Savy57) were used in further studies, presented in Supplementary Material S2.

Discussion

This review provided an overview of the assessment of feeding practices in children under 2 years old using indexes built specifically for this audience throughout the world. A wide range of proposals have been developed aimed at achieving a valid, adequate and viable methodology for a more comprehensive assessment of the diet in this age group, which take into account the complexity of the diet, the profound relationship of food intake with nutritional and health outcomes, the evolution of dietary evidence and recommendations over time.

The study of dietary patterns can be divided into two broad categories of a posteriori and a priori approaches. A posteriori method uses statistical techniques to derive dietary patterns from the food intake, grouping the foods that are often consumed together or putting together people with similar food consumption. Because it is constructed using data from a specific population, this approach may not be reproducible across populations; also, it may not always be able to set the healthiest food patterns, since it is not based on evidence-based dietary guidelines(Reference Smithers, Golley and Brazionis9,Reference Burggraf, Teuber and Brosig60) . On the other hand, the a priori approach is based on current scientific knowledge about food and nutrition and it is composed of variables/components (food, nutrients and other practices) considered important for health, generating measurements of diet quality(Reference Waijers, Feskens and Ocké13). The indexes in this group assess the overall quality of the diet, by comparing the behaviour/practices/food consumption of a population or individual with the current dietary guidelines to define how healthy the diet is(Reference Gil5).

Several indexes have been developed in the last two decades to assess the overall quality of the diet in the first 2 years of life, based on the current global and/or local dietary recommendations for this age group. Over two-thirds of the studies included in this review were published since 2010, and six of them, in 2019 and 2020, which evidences an increased interest in the topic and shows the efforts of researchers in achieving better paths to conduct this assessment.

Most of the studies included in the review were cross-sectional (n 24), which allows associations between diet and outcomes, but without investigating causal relationships. Longitudinal studies can establish stronger evidence about these associations(Reference Lazarou and Newby17). The choice of the index to be used must take into account the study design, as some indexes were built specifically to be used in longitudinal studies and require information at multiple times, such as the one used in the study by Zhu et al (2020)(Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45).

Most studies analysed were conducted in Asian countries (n 12), especially China and India, and Latin American (n = 10) regions that concentrate low- and middle-income countries. These countries still face a major challenge in the double burden of malnutrition, in which malnutrition and overweight, and chronic diseases coexist(Reference Black, Victora and Walker2,Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Allender3) . In this scenario, research on food and nutrition is essential, which may be one of the reasons for the greater interest in the development of methodologies for assessing infant feeding practices in these countries.

Of the thirty-six articles included in this systematic review, 25 % (n 9) were classified as having fair or poor quality, especially due to methodological limitations related to the sample or the analysis process. Nevertheless, the articles included are generally good quality, which also contributed to the quality of the review.

The identified indexes had an extensive variety of evaluated components. Some indexes only assessed food consumption, while others included additional aspects related to the eating practices of children under 2 years old (n 10), developing a more comprehensive approach translating the complexity of the phenomenon. The intake of specific nutrients was evaluated in only one index(Reference Glanville and Mcintyre28), indicating that approaches based on the consumption of foods and/or food groups were most common.

The development of more complex approaches to assess the overall quality of the diet, instead of simple indicators or individual aspects (‘reductionist’ approach), has proved to be a promising approach, a perspective that meets the most current dietary recommendations in countries, for example, the Brazilian Dietary Guidelines for Children Under Age Two(61). This becomes even more relevant in this age group, when intense changes in the child’s diet occur, and there are many variables influencing the feeding practices.

Of the twenty-two original indexes, only thirteen included BF, which is considered a key element for the child’s health and development. Some studies that evaluated children older than one prioritised the consumption of other foods rather than breast milk. Although BF is recommended in a complementary way until the age of 2 or more(1), from 12 months onwards, this practice reduces considerably, while other foods become much more important in the child’s energy and nutrient intake(Reference Boccolini, Boccolini and Monteiro62).

The assessment of the consumption of foods considered unhealthy, with a high content of sugar, fat and salt, such as UPF(Reference Monteiro, Levy and Claro63) appeared more frequently in more recent indexes, justified by the growing trend towards the consumption of these foods and the possible negative consequences of this practice(Reference Bortolini, Gubert and Santos64–Reference Pries, Rehman and Filteau68). Among the thirteen original indexes that evaluated the consumption of UPF, twelve were published since 2012. For indexes that do not evaluate the consumption of UPF, even if the child reaches a high final score, the classification of the diet as good quality could be relative, as it is impossible to assess whether negative feeding practices are also present.

To calculate the index scores, the authors summed the component scores(Reference Ruel and Menon10,Reference Armar-Klemesu, Ruel and Maxwell25,Reference Glanville and Mcintyre28,Reference Kyttälä, Erkkola and Lehtinen-Jacks31–Reference Nyaradi, Li and Hickling36,Reference Ríos, Sinigaglia and Diaz38–Reference Voortman, Kiefte-de Jong and Geelen43,Reference Zhu, Cheng and Qi45) or employed more complex equations(Reference Bell, Golley and Magarey26,Reference Chen, Fung and Fok27,Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29,Reference Koehler, Sichert-Hellert and Kersting30,Reference Ribas, de Rodrigues and Mocellin37,Reference Wang, Dang and Xing44) . The second option requires extra work for final analysis, which may limit their wider use.

The adapted indexes justified the changes to the indexes due to current recommendations, local context or to the available data. The adaptation of existing indexes is a viable alternative to achieve more appropriate measures, whether at the local or global level. This strategy can be strengthened to help improve previous proposals, often with some type of validation, instead of concentrating efforts to create new indexes.

We identified that a relevant gap is the lack of validation of some indexes, which was also an aspect pointed out by Lazarou and Newby (2011) in their review. We checked all the studies that did not report validation to guarantee that those indexes were not validated in previous or later studies. Validation is an important aspect to determine the choice of the most appropriate index for the objectives of the study(Reference Burggraf, Teuber and Brosig60). In the context of dietary assessment, the reference for validating a method would be a comparison with biological nutritional markers(Reference Lazarou and Newby17). However, it is necessary to highlight that regarding infant and young child feeding practices, there is no established gold standard and this may not be necessary because indexes could serve different purposes depending on the context and the diets.

The articles used other measures to assess the validity of the indexes, such as association with nutrient intake, internal validity tests, reliability and repeatability, and association with nutritional status, which added more confidence to the results but were not enough to guarantee that the proposed methodology could properly measure the quality of the diet or identify variations in the diet(Reference Smithers, Golley and Brazionis9,Reference Waijers, Feskens and Ocké13,Reference Marshall, Burrows and Collins19) . The lack of adequate validation of some of the dietary quality indexes has been identified as a problem since the first reviews on this topic(Reference Kant12), and it remains a critical issue in current studies. Smithers et al (2011) also identified in their review this lack of validation of the indexes(Reference Smithers, Golley and Brazionis9). Waijers et al (2007) pointed to arbitrary choices in the construction of the indexes and the lack of perception about the consequences of these choices(Reference Waijers, Feskens and Ocké13).

Regarding their weaknesses, a relevant concern of the researchers is the lack of consensus on the choice of components and the absence of criteria for defining the weight and cut-off points. Some aspects or eating practices may have a greater influence on health and nutrition outcomes than others, so the ideal index would weigh the components in relation to the total score, to more adequately reflect the relationship of the diet with the outcomes. However, evidence remains insufficient to properly establish weights for these parameters(Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29). Some studies try to minimise this limitation, proposing different scores of the same component depending on the age subgroup, for example in the BF component(Reference Ruel and Menon10), or using other calculation procedures(Reference Golley, Smithers and Mittinty29); however, the indexes generally score the components equally.

This difficulty in establishing consensus is not limited to weighting or cut-off points but extends to defining the concept of quality diet or what would constitute an adequate diet(Reference Alkerwi4). In this sense, comparisons between countries can also be difficult. As the cultural contexts or needs can vary greatly by region and across time, establishing a unique approach could be a major challenge for researchers and also limit the possibilities of assessment based on the particular characteristics of places and populations. Thus, the question arises: would a single approach be reliable for universal use or are multiple key approaches more appropriate?

Indexes can be an interesting alternative to provide an overview of a child’s diet quality and are easier to interpret than several separate indicators, but they need to be well constructed and carefully interpreted. Given the above, we can point out some relevant recommendations for future works on this topic. For the components of the indexes, the inclusion of BF assessment is crucial for indexes constructed for younger children, especially under 1 year of age. The construction of the indexes commonly follows the international dietary guidelines, established by the WHO, which does not eliminate the importance of considering the local context. Thus, national guidelines, such as those expressed by food-based dietary guidelines, can also guide the elaboration of the index, for example, in the choice of food groups. The inclusion of an UPF component should also be taken into account, to provide a more complete picture of the quality of the children’s diet. The division by age subgroups can also be a good way to provide a more realistic and reliable assessment, since many changes occur between the introduction of complementary feeding and the age of two.

Strengths and weaknesses

As far as we know, our study is the first to do an extensive investigation of indexes for assessing the feeding practices focusing on children under 2 years old. These include original indexes and studies that have adapted existing proposals, indicating the reasons that led to the adaptations, and pointing out strengths and weaknesses. In addition, studies conducted in countries of all income levels were included.

Selection of an index, among the many existing ones, is not a simple task for a researcher. This choice depends on factors such as study objectives, outcomes of interest, available data and the researchers’ data analysis abilities. Validation is also an important element to assess whether a given index adequately measures the quality of the diet and whether it is associated with important health outcomes related to food and nutrition; however, many studies still do not perform these analyses. Thus, the lack of studies with validation limited the possibility of indicating the most appropriate index to use. This issue is still a gap and demands further study to provide researchers with more reliable parameters.

Conclusions

A wide variety of indexes have been used to assess the eating practices of children under 2 years old, and the list of different components that make up the indexes is also extensive, which is due to the complexity of the issue. The lack of consensus on the concept of diet quality and the peculiarities of this age group contribute to the lack of a reference standard. Cultural and regional differences as well as the evolution of knowledge in the area also present obstacles. Many authors have proposed approaches that contemplate multiple dietary variables and are not limited to individual aspects to achieve a more complete assessment of the diet.

Although there are still gaps, this review showed important steps already taken in assessing the eating practices of young children. The advancement of the proposals, which seek to include multiple components and consider regional and cultural particularities to find the best way to reflect the diet in this age group, provides important aids to continue pursuing the best method.

We emphasise that the adaptation of indexes in accordance with the current recommendations is an interesting alternative, qualifying existing indexes and expanding their possibilities. Thus, a basic proposal that is flexible for modifications according to different scenarios may be a valid option.

Studies with a longitudinal design and validation studies, which evaluate different contexts (urban/rural, cultural, income levels) are important to provide strong and reliable instruments and evidence to support other research and actions directed to the health, nutrition and development of children in their first years of life.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: None. Financial support: The systematic review reported in this paper is part of a PhD project in the Human Nutrition Program at University of Brasilia, Brazil, and the student had a CAPES fellowship (number 88882.383449/2019-01). Otherwise, this research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: P.O.S., A.O.L., S.S.C., L.M.P.S. and M.B.G. formulated the research questions, designed the study and wrote the article. All authors contributed to the editing of the literature review. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethical approval was not required as the paper is a systematic review and the findings of existing studies were available in the public domain.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021000410