In classical conceptualizations of party government, party discipline is a core norm: representatives are expected to share basic values, build policy preferences around them and unambiguously defend the resulting policies in the legislative arena (Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel1993; Willumsen Reference Willumsen2017). Yet, parties are not monolithic actors (Sieberer Reference Sieberer2006). They never were. During the last few decades, however, the growing presence of women in parliament has led to a marked increase in the diversity of policy preferences. Tracing the implications of this development, a number of scholars analysed differences in the legislative behaviour of female MPs, focusing on the drafting and support of bills or giving speeches (e.g. Höhmann Reference Höhmann2020; Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler2005; Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2009). However, whether women in parties lead to a decrease in party cohesion remains underexplored in European democracies (with the exception of Papavero and Zucchini Reference Papavero and Zucchini2018). If gender, indeed, plays a crucial role in legislative behaviour, this pattern should be visible at later, and thus more consequential, stages of the law-making process as well. It is in legislative votes that defection becomes costly: here, deviating votes reveal intra-party conflict and weaken bargaining positions, and thereby increase parties' vulnerability in party competition. At this final stage of the policy process, deviation is more than signalling. It is an act of rebellion undermining the ability of party executives to take effective decisions. Thus, to advance our understanding of how women's presence shapes legislative processes, we address the following research question: does gender affect vote defection from the party line, and if so, under what circumstances?

Existing research, for the most part, focuses on institutional factors, highlighting how electoral systems (e.g. Carey Reference Carey2007), party structures (e.g. Shomer Reference Shomer2009) and electoral competition (e.g. Sieberer Reference Sieberer2006) affect rebellion in parliament. Individual-level factors have received little attention until now (e.g. Sieberer and Ohmura Reference Sieberer and Ohmura2021). Based on studies demonstrating that the gender composition of parliaments shapes policymaking processes and outcomes, we argue that the gender of a Member of Parliament (MP) systematically affects the incentives to vote with or against the party majority. We suspect that social role expectations disproportionately constrain women's leeway to act: deviation entails a higher risk for them as female representatives tend to be judged more harshly, facing stronger penalties than their male colleagues for voting against the party line. Accordingly, women should only deviate if their re-election is secured and in issue areas that are of particular concern to them.

We draw on roll-call vote (RCV) data from the German Bundestag, covering 17 legislative periods from 1953 to 2013 (Bergmann et al. Reference Bergmann, Bailer, Ohmura, Saalfeld and Sieberer2018b), to test our claims. This case is particularly interesting as its mixed electoral system allows us to observe the legislative behaviour of MPs who have to respond to the demands of different principals (Carey Reference Carey2007) while all unobserved country-specific characteristics can be held constant.

Analyses yield surprising results: contrary to our expectations, male and female MPs do not behave as differently as previous research leads us to believe. Only if incentives provided by the probability of re-election and the policy content are taken into consideration, we observe systematic gendered differences in the likelihood to deviate. However, factors such as government participation and contextual settings as proposed by previous research bear a considerably heavier weight in explaining deviation from the party line than the gender of legislators. Our contribution to the field is twofold. For one, in line with previous research, female MPs are more likely than their male colleagues to represent women's interests (e.g. Phillips Reference Phillips1995), even in the high-pressure environment of RCVs: in policy areas that align with women's interests, female MPs are more likely to spark intra-party conflict. These findings call for more attention to how incentive structures the shape of vote defection by men and women differently. For another, this article refines our understanding of legislative behaviour in general, emphasizing that contextual factors still reign supreme in predicting the behaviour of MPs (e.g. Finke Reference Finke2019; Höhmann Reference Höhmann2020), law-making processes (e.g. Volden et al. Reference Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer2013) and policy outcomes (Reher Reference Reher2018).

Literature review: vote defection in parliaments

Across parliamentary democracies, observed party unity is high, implying that defection from the party line is a rather scarce event (for a review see Sieberer and Ohmura Reference Sieberer and Ohmura2021). This cohesion is mainly driven by two factors. Legislators of the same party share core values and interests because they decided to join their party based on exactly these considerations further upstream. The motivation to shape policies efficiently adds to party unity, as party members decide to toe the party line in the public political arena. Further, legislators are dependent on party organizations since these act as gatekeepers for political office, structure collective action and provide significant legislative resources for MPs (e.g. Owens Reference Owens2003; Rahat Reference Rahat2007). As such, parties have carrots and sticks at their disposal to enhance behavioural cohesion among their members. While loyal players are rewarded with influential positions or committee memberships, dissident legislators risk being penalized by party officials for their deviation from the party line. Hence, MPs aiming for re-election very likely adapt their legislative behaviour to party expectations. Nonetheless, a number of factors have the potential to shift the cost–benefit analyses of MPs in favour of deviation. If rebellion is a more promising strategy to reach their goals than subordination, legislators turn against their party.

A growing set of literature argues that political institutions, such as electoral systems (Carey Reference Carey2007) and party nomination strategies (Preece Reference Preece2014; Shomer Reference Shomer2017), are responsible for vote defection in parliament. Electoral system considerations figure most prominently among them, hypothesizing that rules which allow voting for one party only (e.g. closed proportional representation) encourage legislators to adhere to party loyalty. Electoral systems enabling the cultivation of personal votes (e.g. single-member districts and open lists), by contrast, offer more leeway for individualism in parliament, with parties being less relevant for a legislator's political advancement (e.g. Carey Reference Carey2007; Morgenstern Reference Morgenstern2004; Sieberer Reference Sieberer2010). Legislators elected under these circumstances are expected to be more likely to vote in the interests of their constituency versus their party.

Evidence for the effect of electoral systems on legislative voting is, however, mixed. In a cross-national study analysing 23 democracies, Scott Morgenstern and Stephen Swindle (Reference Morgenstern and Swindle2005) demonstrate that the electoral system does not have a clear impact on legislative voting behaviour (see also André et al. Reference André, Depauw and Martin2014; Coman Reference Coman2015; Sieberer Reference Sieberer2006). Aiming to resolve this controversy, Ulrich Sieberer and Tamaki Ohmura (Reference Sieberer and Ohmura2021) take the electoral systems argument from the macro- to the micro-level, showing that electoral safety is the driving force behind electoral system effects in the German Bundestag. Santiago Olivella and Margit Tavits (Reference Olivella and Tavits2014) reveal that another individual-level predictor, local-level political experience, is a strong predictor for defection in legislatures in five European countries.

Taken together, institutions have proved to be a relevant factor in the assessment of vote defection. Yet, the possibility that legislators behave differently under the same institutional structure and in the same political context remains underexplored. As the micro-determinants of legislative behaviour play a central role in the representation of interests in parliamentary democracies, we aim to narrow this gap in literature and explore if and when the gender of MPs shapes the likelihood of vote defection.

Theory: how the gender of MPs influences vote defection

Why would we expect female MPs to differ from male colleagues in their likelihood to defect? Two sets of explanations guide our reasoning. First, gendered differences in MPs intrinsic motivations might inform gendered patterns of vote defection. Gender stereotypes suggest that women are more collaborative and consensual, while men are more likely to act in an individualistic and competitive manner (e.g. Kennedy Reference Kennedy2003; Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal1998; Thomas Reference Thomas1994). These differences in legislative behaviour across genders are thought to stem from socialization – the process in which individuals learn and maintain the norms and values of a society (Liao and Cai Reference Liao and Cai1995). While women are socialized as caretakers who nurture and preserve institutions (e.g. the family), men are taught to compete against opposed interests. Based on this rationale, female MPs should be reluctant to defect from the party line as they are intrinsically motivated to seek compromise and avoid conflict.

A number of studies provide suggestive evidence for this line of argumentation. While women prefer universalistic outcomes and group cooperation in legislative committee decision-making, men opt for competitive solutions (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2003). In legislatures, women tend to apply democratic and consensual strategies by investing more time and effort into creating within- and across-party coalitions (Carey et al. Reference Carey, Niemi, Powell, Thomas and Wilcox1998; Volden et al. Reference Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer2013). Recent literature also indicates that female ministers are more consensus- and compromise-oriented than their male colleagues, thus enhancing coalition stability (Krauss and Kroeber Reference Krauss and Kroeber2020).

Some studies argue that women's preferences for broader coalitional approaches across parties could make partisan voting less likely. However, findings pointing in this direction are derived from analysing legislative behaviour with regard to issues of particular interest to women (e.g. Osborn Reference Osborn2012; Swers Reference Swers2002), covering a subset of issues only. They indicate that cross-party coalition-building depends on structural differences of parties (such as minority party status) (Volden et al. Reference Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer2013) or is used to compensate for a challenging institutional environment (e.g. less than 10% of women's representation) (Wojcik and Mullenax Reference Wojcik and Mullenax2017). Once considering a broader set of policies, a number of studies provide evidence that women stick to partisan and ideological lines (Jenkins Reference Jenkins2012), especially in highly politicized contexts (Frederick Reference Frederick2009), and show higher party cohesion than men in bill sponsorship (Papavero and Zucchini Reference Papavero and Zucchini2018). We suggest that reasons for men's and women's different propensity to defect from party lines might be threefold. First, building on socialization theory, female MPs reluctance to defect from the party line would be an intrinsic motivation to seek compromise and avoid conflict.

Second, the perceived and actual consequences of deviation are different for male and female MPs. For one, expectations of influential political actors (i.e. party officials, group leaders) with regard to women's appropriate behaviour should shape the actual risks attached to deviation. According to the gender incongruency hypothesis (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002), women face harsh judgements once their behaviour violates stereotypical expectations and norms. It is built on the idea that stereotypes originate from belief systems which ascribe different roles to men and women in society, based on their sex. These roles emerge from social position – that is, observable behaviour of men and women in sex-typical roles (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002). As women are assumed to act in a consensus-oriented way, deviation from the party line should be regarded as too agentic or, conversely, not communal enough, and thus would be penalized. Being perceived as disloyal puts their political career and standing within the party at risk, raising the stakes for women who deviate. In line with this rationale, literature from organizational studies shows that women are viewed as untrustworthy when acting incongruously with their prescribed role (e.g. assertive or self-directed) (see e.g. Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002 for an overview). In this vein, Tyler Okimoto and Victoria Brescoll (Reference Okimoto and Brescoll2010) demonstrate that female politicians face a backlash if they violate communal prescriptions. In a large comparative study of party leadership selection, Diana O'Brien et al. (Reference O'Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015) provide empirical evidence that biases against women remain entrenched within political parties and that women face other, often higher, standards than men. Also, Markus Baumann et al. (Reference Baumann, Bäck and Davidsson2019) show that female politicians who deviate from party line in Sweden are indeed more likely to be sanctioned by party leaders: female defectors are less likely to be appointed to ministerial posts than their deviating male colleagues.

For another, women and men are assumed to differ in their relationship towards risk: compared to men, women are found to act in more risk-averse ways (e.g. Croson and Gneezy Reference Croson and Gneezy2009). To account for this phenomenon, some scholars argue that women and men attach different meanings to apparently the same risks due to gendered practices with regard to social roles (Gustafson Reference Gustafson1998), while others expect that gender differences stem from social learning (Booth et al. Reference Booth, Cardona-Sosa and Nolen2014).

Based on these considerations, men's room to manoeuvre should be larger: male legislators more readily take the risks of deviation which are, in addition, lower for them than for their female counterparts. Female MPs, in turn, have a higher incentive to toe the party line as they are assumed to be more risk-averse and aware that an indiscretion on their side might be penalized harshly.

Hypothesis 1: Female MPs are less likely to defect than male MPs.

Even though we expect women to be less likely to deviate, they might do so once the perceived benefits of defection outweigh the costs. One factor shifting this equation is re-election probability, since women and men tend to have different career ambitions and thus varying incentives to toe the party line once re-election is secured. Female representatives tend to focus primarily on staying in office rather than pursuing a position that reaches beyond the elective office presently held (Schmitt and Brant Reference Schmitt and Brant2019). This tendency might, at least partly, be driven by women being more averse to competition (Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2004) and election (Kanthak and Woon Reference Kanthak and Woon2015). In addition, competition for political leadership positions is particularly fierce for women as they face additional hurdles in recruitment processes (Baumann et al. Reference Baumann, Bäck and Davidsson2019; Lawless Reference Lawless2015), higher risks of failing (e.g. Goddard Reference Goddard2019; O'Brien et al. Reference O'Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015) and more personal costs (Galais et al. Reference Galais, Öhberg and Coller2016) than men. The fact that common career paths to higher offices (such as a long pre-parliamentary career and holding several positions within the party) are less feasible or popular for women (Windett Reference Windett2014), especially in Germany (Ohmura et al. Reference Ohmura, Bailer, Meißner and Selb2018), adds another explanation for the predominantly static career ambitions of women.

As career goals shape elective behaviour (e.g. Francis and Kenny Reference Francis and Kenny1996; Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1966; Treul Reference Treul2008),Footnote 1 we expect female MPs to have a certain leeway to express their own political opinion once they have secured re-election. By contrast, male MPs, who tend to have more progressive career ambitions, should have an incentive to gain the support and trust of their colleagues by being loyal to the party even if they have secured the support of the electorate (Francis and Kenny Reference Francis and Kenny1996; Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1966; Treul Reference Treul2008). Based on these considerations, we expect that once women have secured their position, they have less strategic incentives to toe the party line than men who tend to aim for higher political office.

Hypothesis 2: With increasing probability of re-election, female MPs are more likely to defect than male MPs.

Aside from electoral incentive structures, we expect the policy area in which the vote takes place to affect the likelihood of deviation. Women as a group share gender-specific experiences and problems (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Phillips Reference Phillips1995) and are thought to have a particular interest in policies related to feminine issues such as gender equality, social welfare, education, child care, healthcare or family. According to the ‘politics of presence’ argument (Phillips Reference Phillips1995), female politicians take up these distinct preferences of the female electorate when exercising their political role and substantively represent women. In addition to gendered interests, theories of substantive representation (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999) suggest that female MPs feel a certain obligation to push for an agenda that benefits women as a group. This additional mandate derives from women's historical under-representation informing a sense of responsibility to give priority to women's issues. As a result, elected women are more likely to view themselves as representatives of the female population (Xydias Reference Xydias2007, Reference Xydias2013), to regard representing women's interests as an important aspect of their profession (Reingold Reference Reingold1992) and to believe that women are the better representatives of women's interests in parliament (Coffé and Reiser Reference Coffé and Reiser2018).Footnote 2

An extensive set of studies indicate that legislators, indeed, have gendered preference structures and act accordingly. Analysing the link between descriptive and substantive representation, research suggests that female representatives prioritize women-related issues (Thomas Reference Thomas1994; Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2000); are more likely to introduce (e.g. Bratton Reference Bratton2005; Volden et al. Reference Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer2013) and support (Lovenduski and Norris Reference Lovenduski and Norris2003; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2003; Swers Reference Swers2002) bills in the interest of women; are more active on welfare- (Thomas and Welch Reference Thomas, Welch and Carroll2001) and ‘feminine’ committees (e.g. Heath et al. Reference Heath, Schwindt-Bayer and Taylor-Robinson2005); speak more often on women's issues (Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Debus and Müller2014); and are more likely to promote these topics in written and oral questions (Childs and Withey Reference Childs and Withey2004; Höhmann Reference Höhmann2020) compared to their male colleagues.Footnote 3 In addition, a number of studies suggest that women parliamentarians, irrespective of their party ideology, tend to challenge party cohesion by allying across party lines if feminine topics are at stake (e.g. Osborn Reference Osborn2012; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu, Wolbrecht, Beckwith and Baldez2008; Swers Reference Swers2002). Following this line of argumentation, we anticipate female MPs to be more likely to defect from the party line if votes are cast in feminine policy areas.

Hypothesis 3: Female MPs are more likely to defect from the party line than male MPs in feminine policy areas.

Research design

Case selection: vote defection in the German Bundestag

To trace gendered differences in vote defection, we analyse RCV data of the German parliament collected by Bergmann et al. (Reference Bergmann, Bailer, Ohmura, Saalfeld and Sieberer2018b). Covering 17 legislative periods from 1953 to 2013, it constitutes the most comprehensive data set on legislative voting behaviour in the German Bundestag to date.Footnote 4 The Bundestag is an attractive parliament to test the effect of gender on legislative behaviour. It is one of the most powerful legislatures in a parliamentary democracy (Sieberer Reference Sieberer2011) and its mixed electoral system allows us to account for different institutional settings. It thus offers the opportunity to observe the legislative behaviour of MPs who have to respond to the demands of different principles (Carey Reference Carey2007) while all unobserved country-specific characteristics are held constant.

RCVs are one of the most important sources on legislative behaviour as they put the voting decisions of MPs (yes, no, abstain) on public record. Published in the official minutes of the Bundestag, RCVs provide the only instrument to investigate voting behaviour in parliament on the individual level. As in most legislatures, RCVs are not the default mode of voting in the German parliament; roll calls have to be explicitly requested by a parliamentary group or at least 5% of the MPs (Sieberer et al. Reference Sieberer, Saalfeld, Ohmura, Bergmann and Bailer2018).Footnote 5 While early research concluded that position-taking efforts driving RCV requests lead to an overestimation of party cohesion (for the European Parliament: Carrubba and Gabel Reference Carrubba and Gabel1999), more recent literature suggests that policy-seeking objectives reduce cohesion (Finke Reference Finke2015), informing the view that selection biases are negligible (Hix et al. Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2018). Though it is empirically impossible to disprove the claim that RCVs are biased in nature, we do not expect biases to be of major concern to our analysis as we have no reason to suspect that potential selection affects men and women differently. We therefore expect RCVs to be representative of legislative votes, offering the unique opportunity to gain insights into potential gendered patterns of defection in legislative voting.

Our dependent variable, vote deviation, measures deviation from the party line, which is defined as the absolute majority position within the party group in the RCV or, if no absolute majority position exists, the position taken by the chair of the parliamentary party group (PPG). Vote defection is coded 1 if the legislator deviates or abstains, and 0 otherwise. Descriptive statistics (see Online Appendix, Table A1) reveal that rebellion from the party line in the German Bundestag is a rare event: of the 1,127,393 RCVs captured by our data, only 25,450 votes (2.29%) are classified as defection.Footnote 6 Given the disciplining power of parties in the Bundestag (Schüttemeyer Reference Schüttemeyer, Copeland and Patterson1994), this is not surprising and compares to similarly high levels of party voting in other parliamentary democracies (Coman Reference Coman2015), which has not hindered a lively debate on explanatory factors of vote rebellion.

Explanatory variables

Our main explanatory variable, female (Hypothesis 1) is provided by Bergmann et al. (Reference Bergmann, Bailer, Ohmura, Saalfeld and Sieberer2018a), taking the value 1 for women and 0 for men. Aside from gender, we expect the re-election probability of individual MPs to affect their likelihood to defect from the party line (Hypothesis 2). Electoral safety predicts the chances that candidates will be re-elected in each of the German electoral tiers based on the most current available information on their electoral standing (Stoffel and Sieberer Reference Stoffel and Sieberer2018), ranging from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating absolute security to win a seat. We further assume that the subject of votes affects legislative behaviour, with women being more likely to deviate in feminine policy areas (Hypothesis 3). In accordance with Dee Goddard (Reference Goddard2019), our dummy takes the value 1 for RCVs falling into the pre-coded policy areas (Sieberer et al. Reference Sieberer, Saalfeld, Ohmura, Bergmann and Bailer2018) of ‘healthcare’, ‘education’, ‘law, crime and family issues’, ‘social welfare’ or ‘civil rights, minority issues and civil liberties’ and 0 otherwise (see Online Appendix, Table A2).

Control variables

To assess the impact of other factors assumed by extant research to affect voting behaviour, we include a number of individual-, vote- and party-level variables. In addition, we control for time effects by introducing electoral period as fixed effect in our models.

On the individual level, we test for the effect of seniority. Time serving in parliament is negatively linked to the likelihood of deviating from the party line because a higher reputation in the party increases influence on the party line and makes deviation superfluous (see e.g. Kam Reference Kam2009). Furthermore, MPs holding leadership positions should be less likely to deviate from the party line. They have higher stakes as defecting might endanger benefits related to their position, are more likely to shape the party line and hence face less incentive to deviate from it. Office is coded 1 if an MP holds an executive office (e.g. chancellor, cabinet minister or junior minister/parlamentarischer Staatssekretär) or a parliamentary office (e.g. president or vice-president of the Bundestag; chair or vice-chair of a permanent committee; chair or vice-chair of a PPG; party whip/parlamentarischer Geschäftsführer; or chair of a PPG working group) (Sieberer et al. Reference Sieberer, Saalfeld, Ohmura, Bergmann and Bailer2018). In addition, we control for the possibility that the substantial focus of the work of MPs affects the likelihood to deviate. Focus area accordingly measures the frequency of oral parliamentary questions raised in a specific policy area per MP and election period based on data from Tobias Remschel and Corinna Kroeber (Reference Remschel and Kroeber2020). If the motion voted upon lies in the expertise area of an MP, we expect a higher likelihood of defection. We further introduce district, a dummy coded 1 if an MP is elected via district mandate and 0 if running for a list mandate.

On the vote level, we control for an idiosyncrasy of the German legislative protocol: free votes. Free votes are defined as votes where at least one party group waives party discipline and does not give a voting recommendation to its members. Declaring votes free can be appealing out of strategic considerations to hide internal divisions and to avoid conflict on contentious notions (Ohmura Reference Ohmura2014) and thus artificially increase defection.

Our study further includes four party-level controls. First, ideological extremity is assumed to matter for defection, with extreme parties being less ideologically dispersed, showing higher levels of party unity (Rahat Reference Rahat2007) and hence less vote defection. To measure ideological extremity, we use squared Manifesto ratings (Volkens et al. Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2018), with higher values indicating more extreme positions. Second, we account for government participation with a variable taking the value 1 if a legislator is a member of a government party and 0 otherwise. Having more resources to impose discipline on their MPs than those in opposition (Carey Reference Carey2007; Laver and Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1996), defection should be lower in government parties. Third, to control for differences in parties' internal norms and recruitment styles, we include the party dummies CDU/CSU (Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union), SPD (Social Democratic Party), FDP (Free Democratic Party), Greens and Linke (Left). Fourth, the presence of women in parliament should lead to a diversification of interests (e.g. Phillips Reference Phillips1995) that makes rebellion more likely and thus we control for the percentage of women in a party.

Results: how gender shapes vote defection in the German Bundestag

To illuminate the effect of gender on vote defection probability, we conduct a series of logistic regression models with election period fixed effects (see Table 1). Model 1 probes for a general gender gap in vote defection (Hypothesis 1). Model 2 considers the interaction effect of electoral security with gender (Hypothesis 2). Model 3 tests for gender differences in rebellion in feminine policy areas (Hypothesis 3).

Table 1. Logistic Regression of Deviating Votes in the German Bundestag, 1953–2013

Note: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; \dag <0.10. Entries are unstandardized coefficients from a logit regression model. Standard errors in parentheses. Dependent variable is binary: deviation is coded as 1. Election period fixed effects are omitted.

Model 1a (see Table 1) indicates that – contrary to our expectation – women in the German Bundestag are slightly more likely to rebel against the party line than their male colleagues. To investigate this pattern in more detail, we introduce an interaction effect between gender and party affiliation in Model 1b. Figure 1 visualizes the marginal effect of gender on the likelihood to rebel by party. It demonstrates that women's higher likelihood to rebel is mostly driven by women in the FDP who tend to be more likely to deviate from the party line than their male colleagues. The same tendency applied to female members of the SPD. Women in the Greens are, in contrast, less rebellious than their male colleagues (p < 001). Effect sizes are, however, very small. Gender does not significantly explain differences in voting behaviour for MPs of the CDU/CSU and Die Linke.

Figure 1. Marginal Effects of Gender on the Likelihood of Vote Defection by Party (with 90% Confidence Intervals)

Note: Figure based on Model 1b in Table 1.

Yet, Figure 1 indicates that variation in vote defection is larger across parties than within parties. Thus, the impact of gender on the roll-call voting behaviour of MPs tends to depend on party affiliation, in line with findings from the US Senate (Frederick Reference Frederick2010). As suggested by previous studies, women seem to be mainly divided along partisan lines with only slight differences from their male colleagues of the same party (Frederick Reference Frederick2009; Jenkins Reference Jenkins2012; Papavero and Zucchini Reference Papavero and Zucchini2018; Simon and Palmer Reference Simon and Palmer2010). In sum, these findings do not support Hypothesis 1 but suggest that a disaggregated view on gender differences in legislative behaviour is crucial as differences between parties might offset effects.

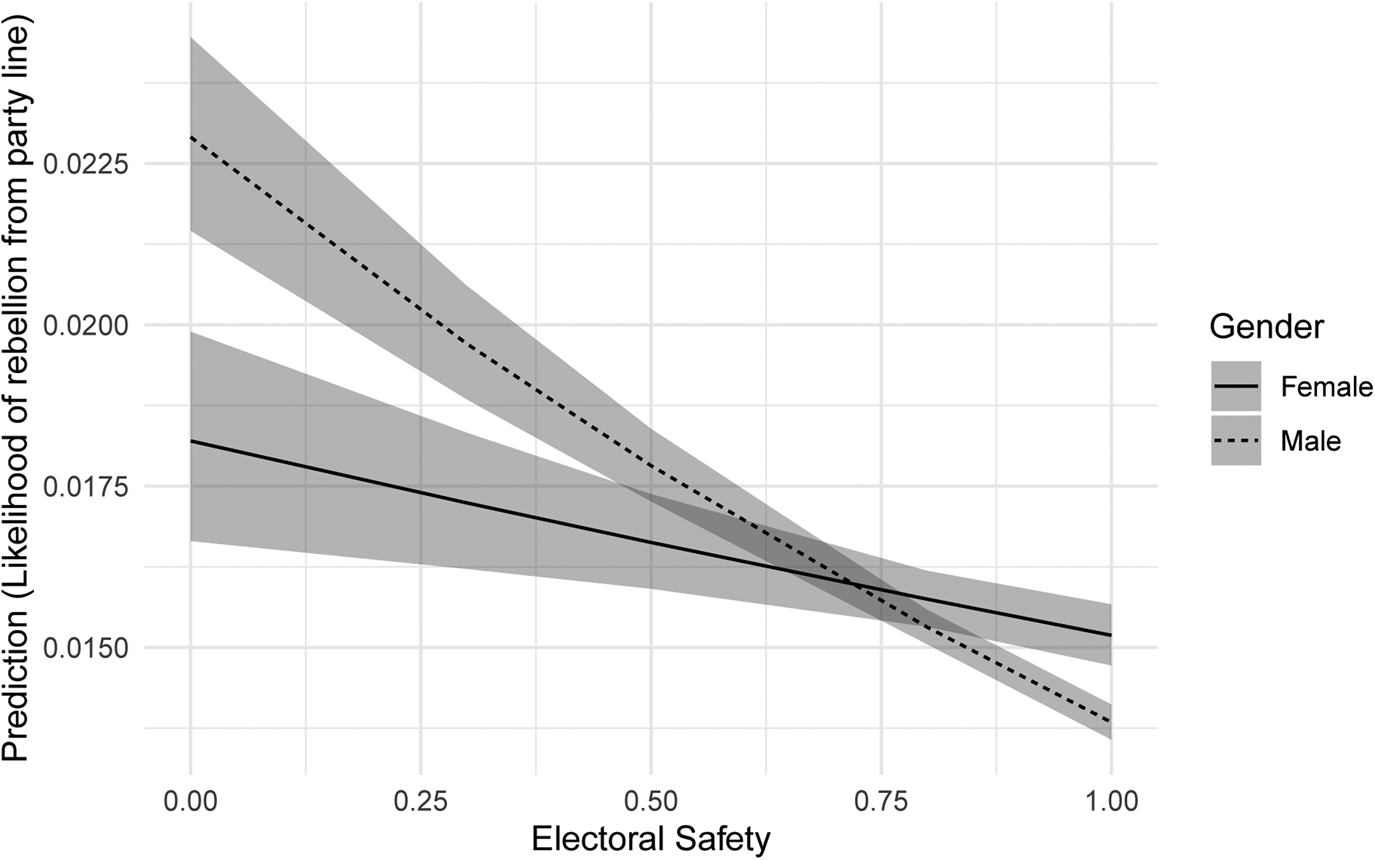

Model 2 tests Hypothesis 2's proposal that men and women react differently to increases in electoral safety. Overall, the re-election probability for all MPs has a negative effect on vote defection, implying that MPs become less likely to deviate with increasing electoral security. The interaction between gender and electoral security indicates, however, that men and women react differently: while men's predicted probability of deviating from the party line falls from 2.29% at minimum electoral security to 1.38% at maximum, women's decrease is considerably smaller (1.82% to 1.52%), leaving women at a higher probability of deviating than their male colleagues at high levels of re-election probability.

Figure 2 visually displays the interaction between gender and electoral safety and illustrates that this effect is not driven by an increasing likelihood of women deviating at higher levels of electoral security – as theoretically assumed – but by a smaller decrease in their defection probability compared to men. Female MPs seem to react little to incentive structures provided by the prospect of another term in parliament. By contrast, men, who are expected to have more progressive career ambitions, strongly adjust their behaviour and become increasingly loyal to their party as re-election probability increases. Election prospects, hence, do not seem to influence the vote-defecting behaviour of men and women at similar rates: re-election prospects seem to matter more for male MPs. This finding reflects previous literature that indicates that, generally, male MPs adjust their legislative agendas to career prospects in the US Congress (Schmitt and Brant Reference Schmitt and Brant2019). Taken together, we find support for Hypothesis 2 that female MPs are more likely to defect than male MPs as re-election probability increases, yet can only partly corroborate the proposed mechanism.

Figure 2. Marginal Effects of Gender and Electoral Safety on the Likelihood of Vote Defection (with 90% Confidence Intervals)

Note: Figure based on Model 2 in Table 1.

Turning to the content of motions, Model 3 includes an interaction effect between policy area and gender to probe whether women are more likely to deviate in votes cast in feminine policy areas than men, as proposed in Hypothesis 3. Results reveal that the content of motions, indeed, affects men and women's likelihood of rebelling differently. While male and female legislators do not significantly differ in their defection probability in non-feminine policy areas, gender differences appear once issues of disproportionate importance to women (such as welfare policy, healthcare or education) are voted upon. While female MPs have a predicted probability of deviating in feminine policy areas of 2.44%, men's likelihood to deviate is at 2.01% (see Figure 2). Taking a closer look at the within-women differences, the scope of this effect becomes comprehensible: with a predicted probability to defect in other policy areas of 1.59%, women's likelihood to deviate from the party line increases by 55.04% if the motion voted upon lies in feminine policy areas. In line with our Hypothesis 3 and as suggested by previous research (Coffé and Reiser Reference Coffé and Reiser2018; Xydias Reference Xydias2007, Reference Xydias2013), female legislators pick a side – they challenge party cohesion once feminine issues are at stake (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Marginal Effects of Gender and Policy Content on the Likelihood of Vote Defection (with 90% Confidence Intervals)

Note: Figure based on Model 3 in Table 1.

Taking a glance at control variables, findings suggest that effects are stable across model specifications and mirror previous research. On the individual level, results reveal that holding a parliamentary or executive office significantly reduces the probability of MPs deviating, a finding in line with existing research (Sieberer Reference Sieberer2010). Seniority, according to expectations, increases the likelihood to deviate. The effect of mandate type points in the expected direction: parliamentarians elected into office via the district tier are more likely to deviate than their colleagues with list mandates. In accordance with theory, legislators are also more likely to deviate from party lines in their focus area of work. On the vote level, expectations regarding free votes are confirmed: deviation becomes significantly more likely if party discipline has been waived. Turning to the party level, government participation has a disciplining effect on legislators' behaviour, resulting in a lower likelihood of deviation if an MP is a member of a government party (Carey Reference Carey2007; Laver and Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1996). The odds of defection further decrease as ideological extremity increases, indicating that members of centrist parties are more likely to defect than their colleagues in ideologically more extreme parties (Rahat Reference Rahat2007). An increasing share of women in a party, by contrast, raises the overall likelihood of legislators defecting, suggesting that MPs react to a diversification of the legislature. Overall, our findings suggest that gender affects vote defection – but only to a comparatively small degree. If we consider incentive structures and the content of motions, gender, indeed, shapes defecting behaviour. In line with previous research, however, contextual factors such as government participation bear a considerably greater weight on vote defection.

Conclusion

Assessing the determinants of vote defection has attracted considerable attention. Yet, previous research has overlooked the increasing diversity of perspectives that rising numbers of women in parliament have brought along. Contributing to a more complete account of legislative behaviour, we tested whether gender shapes the odds of party (dis-)loyalty.

Analysing RCVs in the German Bundestag (1953–2013), this article indicates that gender affects vote defection – but only to a small extent. Once we take incentive structures provided by electoral security and policy content into consideration, male and female legislators behave differently. Men are less likely to be loyal to the party than women if re-election probability is low, while female legislators are more likely to consider defection from the party line in policy areas that are important to them.

Given the high-pressure environment in which RCVs are taking place, these gender differences in voting behaviour are indicative of gender gaps. If we see gender differences here, we have reason to assume that they also exist across other levels of policymaking. Nonetheless, we want to call attention to the size of these effects: our analyses echo previous research, showing that contextual factors such as government participation are the main drivers of vote rebellion.

The implications of this study are twofold: first, speaking to the literature on party cohesion, the results suggest that institutional-level factors still reign supreme when it comes to predicting vote defection. Political gatekeepers seem to succeed in selecting candidates with preferences that are in line with the party position. This way, selectors increase reliability towards the electorate and the likelihood of achieving shared policy goals once in parliament. Yet, under certain circumstances, legislators follow their own agenda, and gender shapes, to some degree, whether MPs take the risky decision to rebel against the party line. Second, in line with literature suggesting that female MPs are more likely than men to act on behalf of women in the electorate (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Phillips Reference Phillips1995), our results imply that in the high-pressure environment of RCVs as well, female legislators follow their own agenda if ‘feminine’ policy issues are at stake.

Future studies might want to explore the generalizability of our findings across countries and over time. So far, research testing for the effect of gender on legislative party cohesion relies on case studies only. Understanding the dynamics of the interaction between gender and legislative deviation in different contexts would provide us with a more fine-grained picture of vote rebellion. A particularly fruitful avenue for research might be tracing the effect of intra-party selection processes and recruitment structures across parties on gender differences in rebellion. Taken together, our research calls for a disaggregated view on voting behaviour that helps us to discern when women rebel.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.40.

Acknowledgements

We thank Yannick Stiller, Gabriele Spilker, the editors and two anonymous reviewers for comments and suggestions that greatly improved this contribution.