Why study Japan? For political scientists who conduct research, education, and policy engagement related to Japan, this is a fundamental question. At the individual level, there are surely a wide variety of answers to the question: a formative experience, an uplifting mentor, or inspiring class. In my own case, it was a combination of all three, but Susan Pharr's role cannot be overstated: as my Ph.D. advisor at Harvard, she encouraged my interest in Japan and gave me crucial advice about how to incorporate research on Japan into scholarship with broader appeal. For an even longer time thereafter, she provided invaluable support as a lifelong mentor and colleague. It is thus a distinct honor to contribute to this festschrift issue in honor of Susan's career.Footnote 1

In this article, I consider the role of research on Japanese politics and foreign policy within the broader field of political science. I begin by examining scholarship that deals with Japan in English-language academic journals over the last 40 years, which corresponds to the most active period of Susan's career. An overview of publications in both top political science journals and area studies journals indicates a thriving subfield. Japan-related publications in area studies journals have increased considerably over the past four decades, and there has been no corresponding decline of articles placed in top political science journals.

Nonetheless, Japanese politics research faces nontrivial headwinds within the broader field. This can be attributed to two factors: (1) general skepticism toward area studies by some scholars, who prefer to see the field focus on general theories with wide applicability to a variety of countries or the entire international system; and (2) the relative geopolitical and economic decline of Japan, which has diminished the perceived substantive importance of the country as a potential geopolitical competitor or powerhouse.

Japan scholars have responded in several ways to such skepticism. First, some scholars have brushed the critics aside and continued publishing Japan-specific research that sheds lights on important features of the country's politics and institutions. Second, others have incorporated empirical evidence from Japan within broader research programs that evaluate general theories of comparative politics or international relations. Both approaches have produced important contributions to the field, but they are also associated with important shortcomings that marginalize Japan, albeit in different ways.

The remainder of the article will focus on a third approach, which is equally compelling but generally receives less attention. I argue that Japan is a Harbinger State, which experiences many significant challenges before other countries in the international system.Footnote 2 As such, studying Japan can inform both scholars and policymakers about the challenges and political contestation other countries will likely confront in the future. Careful study of Japan can thus yield theoretical insights and early empirical evidence related to substantively important political issues of general interest.

After defining and laying out my conceptualization of the harbinger state, I will outline how Japan has plausibly held the status of harbinger within the areas of economic transformation, demographic and social transformation, and international relations transformation. I then consider several reasons why Japan is a step ahead of other countries in some areas but not others: selective openness to change, geographic location, and constitutional constraints. Finally, I will conclude with a summary and discussion of broader implications.

1. State of scholarship about Japan in political science

In this section, I will survey the state of Japan studies in political science using data on English-language journal publications. The data cover the last 40 years, a period that roughly corresponds to Susan Pharr's academic career. It suggests that research on Japanese politics and foreign policy remains robust despite common perceptions to the contrary: over the last 40 years, there has been a large increase in the volume of Japan-related articles and no meaningful decline in share of space devoted to Japan in top journals.

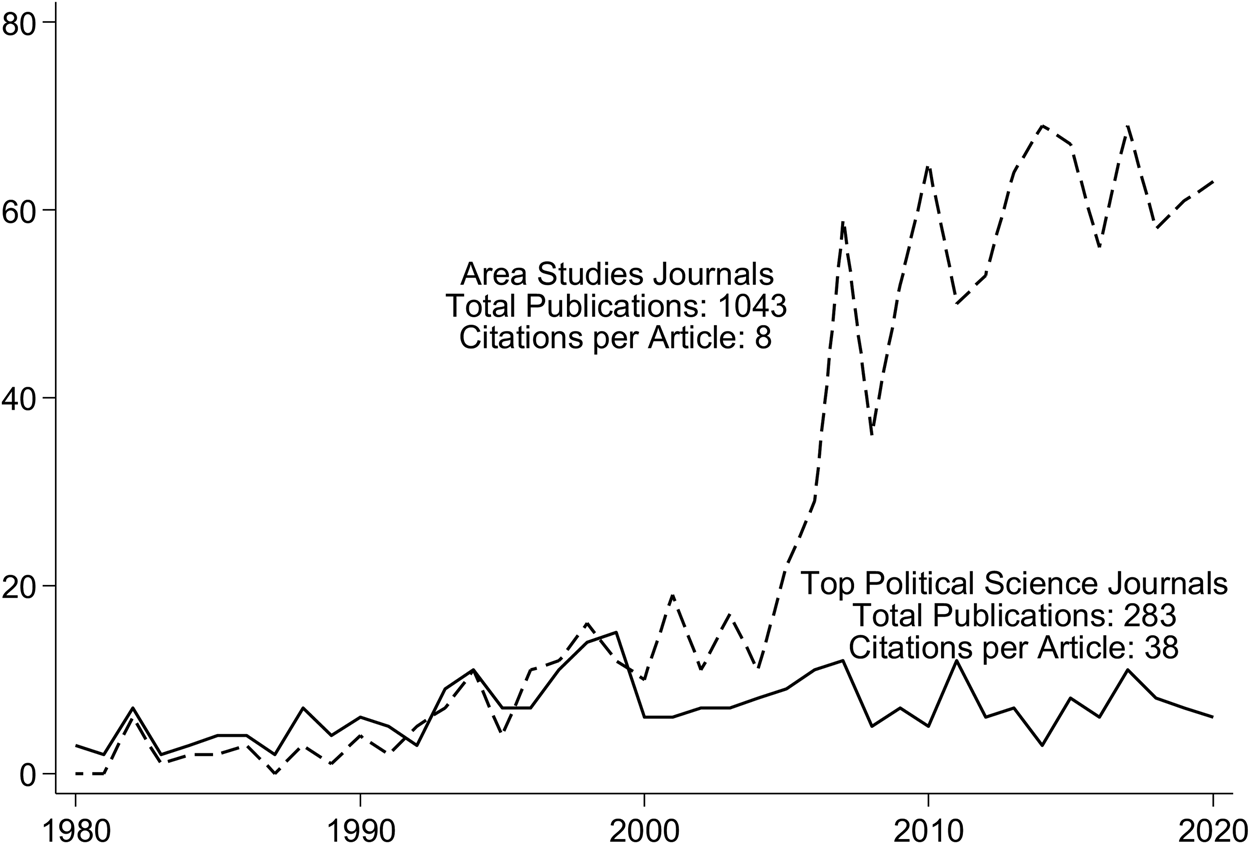

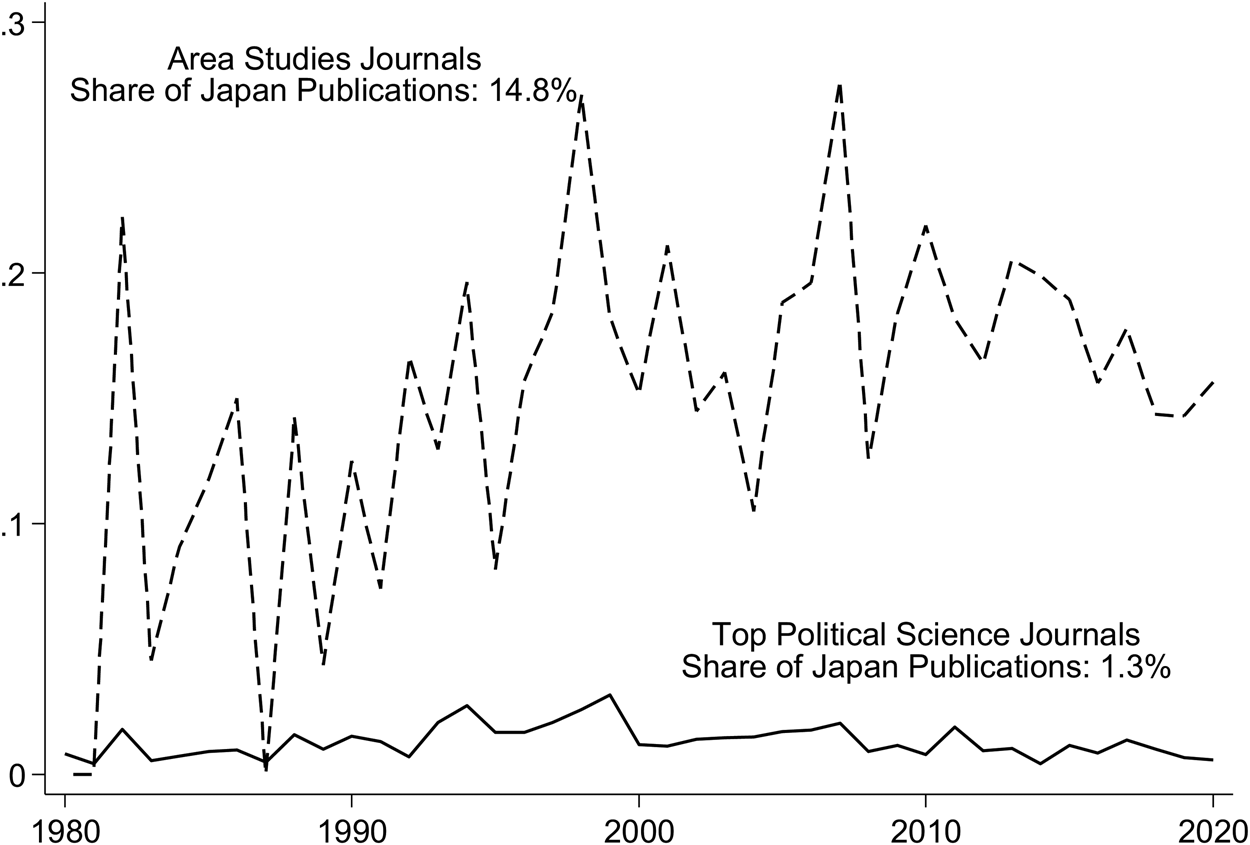

Figure 1 plots the number of publications related to Japanese politics or international relations in two sets of outlets during 1980–2020: (1) the top 15 political science journals and (2) area studies journals.Footnote 3 Figure 2 similarly plots shares. The main shift that stands out from the figures is the substantial increase in publications related to Japanese politics in area studies journals, with a particularly large increase since the mid-2000s. This largely reflects an increase in the number of area studies journals published: the Japan-share of articles in such journals does not exhibit a comparable increase.

Figure 1. Number of annual publications on Japanese politics and international relations: area studies journals and top fifteen political science journals (1980–2020).

Figure 2. Share of annual publications on Japanese politics and international relations: area studies journals and top fifteen political science journals (1980–2020).

Contrary to common perception, the increase in Japanese politics articles in area studies journals has not come at the expense of publications in top political science journals. The number of publications about Japan in such journals has largely held steady over the last 40 years. Shares have also been largely flat at around 1–2%. The figures understate the impact of research on Japan, as they only count English-language articles in which Japan is mentioned in the title, abstract, or keywords. Japan is often used as a case or source of data in many additional studies. Furthermore, important work on Japanese politics is published in books and edited volumes, Japanese-language publications, and lower-ranking political science journals, which are not part of the figures.

A total of 1–2% of articles published in top political science journals may seem like a low figure, but it is important to remember that top political science journals are subject to idiosyncratic biases that suppress the volume of publications on a variety of substantively important topics. The most important bias is the one in favor of single-country studies of Western states, particularly the USA. For example, there are more articles on a single US institution, Congress, than all articles on Japan, Korea, and India combined. A simple topic search on the names of recent US presidents produces more top journal publications than those devoted to major countries.Footnote 4 Furthermore, top journals have often neglected topics such as financial crises, climate change, and pandemics as ‘not of general interest’ despite their obvious substantive importance: these topics also typically occupy less than 2% of space in top political science journals (Lipscy, Reference Lipscy2020).

It is thus important to premise what follows by making it clear that there has been no meaningful decline of Japan studies in political science to date. The volume of Japan-related journal publications has increased considerably over time. Although the data do not measure quality, it is also clear that the sophistication of such research has grown markedly, reflecting increasing linguistic and cultural fluency along with a variety of theoretical and empirical approaches that were unavailable to earlier researchers.

Relatively speaking, more articles about Japan are published in area studies journals in recent years. This may contribute to the perception that it has become difficult to publish Japan-related work in the discipline's leading journals. However, this mirrors a broader pattern in the discipline that is in no way exclusive to Japan studies – due to greater submission volumes and declining acceptance rates at top journals, virtually every subfield has experienced a relative shift toward specialized journals. This includes general subfields that are not subject to concerns about declining attention, such as security studies and international political economy.Footnote 5 Furthermore, there has been a migration of qualitative research toward specialized journals and books across subfields as top disciplinary journals increasingly emphasize causal inference using quantitative methods. The placement of Japan-related research has shifted analogously.Footnote 6

2. Why Japan? Skepticism and responses

Let us now return to the opening question: why study Japan? For many scholars of political science, an individual answer to the ‘why’ question is sufficient. An academic who studies topics such as political economy, democratic institutions, or international organizations usually only needs to provide a cursory statement about substantive importance. However, a scholar of Japanese politics faces greater scrutiny. Part of this is ideological, reflecting the ascendance of scholars deeply skeptical toward area studies in the broader discipline. For example, a prominent colleague once discouraged me from studying Japan on the grounds that ‘It's not political science if you're studying something that's a proper noun!’ According to this view, political science is a field that develops general theories and identifies empirical regularities that hold beyond a single-country context. To use an analogy from chemistry, theories are only valuable if they explain patterns common to the 118 elements of the Periodic Table – there is little utility in understanding specific states or characteristics of individual elements such as sodium and chlorine or how they might interact.

A second type of skepticism is of the realpolitik variety. Stated bluntly, some countries or regions may be worthy of dedicated attention because of their geopolitical or economic weight in the international system: understanding the politics and foreign policy of China or India may be justified on geopolitical grounds that are less convincing for New Zealand or the Maldives. According to this view, Japan might have deserved special status in the late-twentieth century when it grew rapidly and potentially threatened US preeminence. However, the situation has changed as the country gradually descends international ranking tables across a variety of measures, as illustrated in Table 1. Japan is still one of the largest economies in the world, a leading democracy in the world's most dynamic region, and key US ally. Nonetheless, it is undeniable that Japan's geopolitical weight in the world has declined in relative terms.

Table 1. Japan's international ranking

Notes: All financial values are in current US dollars.

Sources: World Bank, World Development Indicators; OECD Development Finance Data; SIPRI Military Expenditure Database.

2.1 Three responses to skepticism

How have scholars of Japanese politics addressed skepticism from the broader field? There are at least three common responses: (1) to dismiss the skeptics and study Japan as a country important in its own right; (2) to conduct broad, generalist research that incorporates Japan as a source of empirical evidence; and (3) to study Japan to generate theoretical ideas that have wide applicability to other country contexts. All three approaches have strengths and weaknesses, and there is important scholarship associated with each of them. It is not my intention to suggest that any of them should be abandoned in favor of another. However, the third approach – Japan as a source of general theory – seems to receive less attention compared to the other two.

The first response is to ignore the skeptics and continue studying Japan as a country inherently worthy of dedicated attention. The most vehement defense of this approach holds that Japan is basically unique, ‘what science calls a true anomaly’ that defies explanation based on theories and models developed in other contexts (Johnson and Keehn, Reference Johnson and Keehn1994). A more nuanced case can be made on the grounds that it is important to counteract pernicious biases in the field, such as the longstanding overemphasis on the Western experience in political science (Williams, Reference Williams1995; Kang and Lin, Reference Kang and Lin2019). The trivialization of scholarship on specific countries such as Japan is logically incoherent within a discipline that simultaneously dedicates an entire subfield, along with faculty lines and journal space, to single-country scholarship on American politics. Despite the decline of Japan in various international ranking tables, the politics and political economy of Japan remain no less fascinating today than it was in the 1990s.

The advantage of this relatively uncompromising approach is its flexibility, which allows researchers to explore any topic about contemporary Japan utilizing a variety of theoretical and empirical approaches. Scholarship in this vein has played an important role in characterizing and explaining core features of postwar Japanese politics such as its political parties, bureaucracy, and policy formulation processes (Curtis, Reference Curtis1971, Reference Curtis1988; Johnson, Reference Johnson1982; Samuels, Reference Samuels1987; Okimoto, Reference Okimoto1990; Calder, Reference Calder1991; Kato, Reference Kato1994; Schoppa, Reference Schoppa1996; Kohno, Reference Kohno1997; Krauss and Pekkanen, Reference Krauss and Pekkanen2011) as well as specific issue areas such as economic and financial policy (Rosenbluth, Reference Rosenbluth1989; Amyx, Reference Amyx2006; Vogel, Reference Vogel2006; Park et al., Reference Park, Kojo, Chiozza and Katada2018) and security policy (Green, Reference Green2001; Samuels, Reference Samuels2008; Oros, Reference Oros2017; Smith, Reference Smith2019; Le, Reference Le2021). Edited collections that trace major developments in Japanese politics based on broad themes or during specific time periods have also contributed important insights and served as crucial repositories of knowledge (Okimoto and Rohlen, Reference Okimoto and Rohlen1993; Reed et al., Reference Reed, McElwain and Shimizu2009; Gaunder, Reference Gaunder2011; Kushida and Lipscy, Reference Kushida and Lipscy2013; Pekkanen et al., Reference Pekkanen, Reed and Scheiner2013, Reference Pekkanen, Reed and Scheiner2015, Reference Pekkanen, Reed, Scheiner and Smith2018; McCarthy, Reference McCarthy2020; Hoshi and Lipscy, Reference Hoshi and Lipscy2021; Pekkanen and Pekkanen, Reference Pekkanen and Pekkanen2022).

Japan-specific scholarship can place the country in comparative context while shedding light on distinctive features of the Japanese political system that may be neglected in a broader study. Several of Susan Pharr's pivotal contributions carefully examine how the politics of an issue of general interest – such as protests and the role of the media – play out specifically in Japan, sometimes in unique ways attributable to particular institutions and norms (Pharr, Reference Pharr1990; Krauss and Pharr, Reference Krauss and Pharr1996). Distinctive features of Japanese politics and institutions – such as corporatism without labor (Pempel and Tsunekawa, Reference Pempel, Tsunekawa, Schmitter and Lehmbruch1979), egalitarianism without a European-style welfare state (Estevez-Abe, Reference Estevez-Abe2008), or the key role of off-budget financing through the postal savings system and Fiscal Investment and Loan Program (Park, Reference Park2011; Maclachlan, Reference Maclachlan2012) – can provide important correctives within a discipline that tends to rely heavily on theories and evidence drawn from Western countries.

The principal disadvantage of this approach is that it may contribute to the marginalization of Japan studies within political science, as single-country studies are increasingly difficult to place in high-ranking academic journals and academic presses. They also tend to attract less scholarly attention. Figure 1 illustrates both points: while the number of publications about Japanese politics has climbed considerably in recent decades, articles published in area studies journals tend to receive fewer citations. Nonetheless, such studies remain valuable in shedding light on underappreciated aspects of Japanese politics that may be difficult to slot neatly into prevailing debates in the broader discipline.

The second response is to incorporate Japan into the empirical section of a study framed more broadly. In this formulation, Japan serves as a case study in support of a more general, comparative theory or offers some feature advantageous for causal inference. Many contributions in this vein are situated within broader research programs or collections featuring scholars with diverse country expertise. Japan has occupied a prominent place in important cross-national, collaborative studies on topics of broad interest such as democratic governance (Pharr and Putnam, Reference Pharr and Putnam2000), one-party dominance (Pempel, Reference Pempel1990), internationalization and domestic politics (Keohane and Milner, Reference Keohane and Milner1996; Rosenbluth, Reference Rosenbluth, Keohane and Miller1996), varieties of capitalism (Estevez-Abe et al., Reference Estevez-Abe, Iversen, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001), and constructivist approaches to security studies (Berger, Reference Berger and Katzenstein1996; Katzenstein, Reference Katzenstein1996). The substantial literature that evolved around the consequences of Japan's electoral reform of 1994, which some scholars describe as a ‘natural experiment,’ follows this model (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Rosenbluth and Thies2000; Giannetti and Grofman, Reference Giannetti and Grofman2011; Catalinac, Reference Catalinac2016; Goplerud and Smith, Reference Goplerud and Smith2021). Japan has also been examined as a key case to address general, substantive questions in areas such as trade policy and the evolution of the international order (Davis, Reference Davis2003; Naoi, Reference Naoi2015; Lipscy, Reference Lipscy2017; Goddard, Reference Goddard2018; Funabashi and Ikenberry, Reference Funabashi and Ikenberry2020). Another common approach is to leverage some feature of Japan advantageous for causal inference – e.g., as-if random assignment of attributes such as the timing of municipal elections and candidate surnames – or to conduct survey experiments on Japanese subjects to examine questions of broader significance (Fukumoto and Horiuchi, Reference Fukumoto and Horiuchi2011; Fukumoto and Miwa, Reference Fukumoto and Miwa2018; Kitagawa and Chu, Reference Kitagawa and Chu2021).

The advantage of this approach is that it is a reasonably reliable way to publish research about Japan in high-ranking disciplinary journals, which increasingly emphasize internal validity and causal identification (Pepinsky, Reference Pepinsky2019). The disadvantage of the approach is that it tends to diminish the importance of studying Japan per se – in many cases, a different country could be substituted for Japan without great consequence for the scholarship. For example, Italy or New Zealand could be examined as other notable cases of electoral reform (Norris, Reference Norris1995), and a survey experiment on Japanese subjects could be easily replicated in another country. Familiarity with contemporary Japanese politics is essential to identify opportunities for credible causal inference or understand the nuances of major changes such as electoral reform. Developing area expertise in Japan involves nontrivial costs, such as the acquisition of language, cultural fluency, and networks among scholars and policymakers. This may contribute to a different kind of marginalization, as emerging scholars shy away from Japan in favor ‘easier’ or more familiar countries.

A third response seeks to combine the advantages of the first two approaches: namely, to develop theories around political challenges or policy responses that are distinctly Japanese but nonetheless have significant implications for the study of a broader set of countries. If feasible, this third response holds considerable promise for scholars of Japan. While the first two responses marginalize Japan in one way or another, the third response puts Japan studies front and center as the source of theoretical insights that hold major significance for the rest of the field. In the remainder of this essay, I will argue that Japan's status as a harbinger state makes this approach plausible and promising.

3. Harbinger state

I define a harbinger state as a country that engages in the politics of a particular issue prior to other countries. There are three conditions that must be satisfied for a country (or other political unit) to be considered a harbinger. The first condition concerns timing: the country must be early in confronting a new issue or challenge relative to other countries. The challenge need not be completely unprecedented: it may represent an unfamiliar phase or novel variation within a given issue area. A key question is whether the challenge can be addressed unproblematically with standard political arrangements and policy remedies that have been applied previously. For example, COVID-19 was neither the first pandemic nor even the first outbreak triggered by a SARS-CoV virus. Nonetheless, the virus was characterized by a combination of distinct features – e.g., asymptomatic spread, airborne transmission, and relatively high virulence – that made it difficult to contain using existing containment measures, thus necessitating an unprecedented political response.

Second, there must be a reasonable expectation that the issue in question will emerge with a lag elsewhere. Being early is not necessarily indicative of being a harbinger. The European Union is often heralded as a model of regional integration, but the project draws strength from commonalities among its member states – such as liberal democracy, economic development, and history – that are much weaker in other parts of the world. It is thus plausibly sui generis (Phelan, Reference Phelan2012). The politics of telecommunications regulation in Japan offers another example. Although Japanese firms were often far ahead of their global competitors in developing features for mobile handsets and other advanced products, they were trapped in a ‘Galapagos’ ecosystem that thrived only in the Japanese market, a pattern described as ‘leading without followers (Kushida, Reference Kushida2011).’ Thus, the issues confronted by telecommunications regulators in Japan did not foreshadow emerging challenges elsewhere.

Third, a country's status as a harbinger should not be established solely through imposition. There are some issue areas in which being early is advantageous and thus a matter of contestation. Some states play an outsized role in global standard setting due to their geopolitical and economic power, which generates strong incentives for other countries to follow their regulatory lead (Drezner, Reference Drezner2007). Powerful states can directly or indirectly intervene in the affairs of weaker states, creating followers through coercion. Government officials in a harbinger state may certainly see merits in promoting the advantage of its own response and seeking emulators. However, the artificial creation of leader–follower relationships through coercive power should be considered a different phenomenon: e.g., the Soviet Union was not a harbinger state vis-à-vis other members of the Warsaw Pact.

Considerable existing scholarship focuses on the experiences of Western states as harbingers for political developments and contestation elsewhere. The UK in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries has been often studied as a frontrunner in the development of constitutional constraints on government authority, which had significant political consequences that later affected many other states (North and Weingast, Reference North and Weingast1989; Schultz and Weingast, Reference Schultz and Weingast2003). Early industrialization in the UK informed both policy among and scholarship about late-industrializing countries (Gerschenkron, Reference Gerschenkron1962). Classical work in comparative politics and international relations often consisted of extrapolating the political development and relationships among Western states into purportedly generalizable theories applicable to all states (Lipset, Reference Lipset1959; Waltz, Reference Waltz1979).

The focus on select Western countries in the existing literature is not wholly unjustified given their early industrialization and experience with associated societal and political transformations. However, the status of Western countries as harbingers can no longer be taken for granted. Countries such as the UK and USA have lost their status as clear economic and technological frontrunners, thanks to the rapid development and transformation of other countries, including non-Western states such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and increasingly China. Democratic institutions are under intense pressure in the USA and European countries in ways largely familiar to experts of democratic backsliding in other parts of the world (Levitsky and Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018). Scholars are increasingly questioning international relations scholarship that presumes the unproblematic generalization of Western-centric theories (Kang and Lin, Reference Kang and Lin2019; Zvobgo and Loken, Reference Zvobgo and Loken2020).

In the remainder of this article, I will consider the status of Japan as a harbinger state. I will argue that Japan has emerged as a harbinger across a range of issue areas and consider some of the reasons why this may be the case. It is not my intention to assert that Japan's status as a harbinger is unique. Other states surely play an analogous role depending on the specific issue area. The observations in this article are written with Japan in mind, but they thus have wider implications for the study of other countries and political units.

4. Japan as a harbinger state

In 1979, Ezra Vogel emerged as perhaps the most influential early advocate of the idea that Japan offers important lessons for other states, including those in the West. In Japan as Number One: Lessons for America, Vogel intentionally highlighted areas of Japanese strength – such as guidance by an elite bureaucracy and emphasis on consensus – that were mirrored by glaring weaknesses in America (Vogel, Reference Vogel1979). Less sophisticated, oftentimes uninformed revisionist narratives that overhyped the virtues of Japanese political, economic, and social institutions proliferated in the 1980s and early 1990s.Footnote 7

In 1979 – the same year Vogel published Japan as Number One – the Ministry of International Trade and Industry offered a cautionary observation, noting that ‘a turning point is coming, a move away from an industrial pattern of “reaping” technologies developed in the seedbeds of the West, to a pattern of “sowing and cultivating” that displays greater creativity. With the century of catch-up modernization at an end, from the 1980s onwards we will enter a new and unexplored phase.’Footnote 8 This prescient analysis foreshadowed the difficulties Japan would face as it sought to transition to a country at the economic and technological cutting edge. In 2007, Komiyama Hiroshi, then President of the University of Tokyo, argued that Japan had transitioned from an era of catch-up to frontrunner as a kadai senshinkoku (an advanced country in problem management) in areas such as the environment, energy, medicine, and education (Komiyama, Reference Komiyama2007). This language has been increasingly incorporated into Japanese government documents as the country confronts challenges that have no clear precedent elsewhere (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (Japan), 2010; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2012; Cabinet Secretariat (Japan), 2014).

It is important to emphasize the distinction between Japan as a leader and Japan as a harbinger. Scholars such as Vogel saw in Japan features that were admirable, effective, and worth imitating. However, for the most part, these features have not actually found emulators. Rather than reflecting an early response to universal challenges, the institutional strengths highlighted were often deeply rooted features of Japanese political, economic, and societal institutions. Even if Japan was a true leader on account of these institutions – a highly debatable proposition – exporting them would require wholesale reorganizations in other countries of equally well-established institutions, which would encounter fierce resistance. As Nobutaka Ike noted in his critique of Vogel's book: ‘The American Congress would certainly resist any attempt to reduce its power to legislate, and, whatever its advantages, the American public would very likely regard the elevation of the federal bureaucracy to a position comparable to that occupied by its Japanese counterpart as too high a price to pay (Ike, Reference Ike1980).’

Revisionist scholarship characterized Japan as a source from which to draw inspiration rather than a harbinger for what was to come. It was thus natural that the genre faded away after the 1990s along with Japan's economic stagnation and concurrent US economic reinvigoration. There were several areas where practical Japanese business practices were incorporated widely and became international standards – e.g., kaizen (incremental improvements), just-in-time inventory management, and various design principles. However, rather than finding Western emulators, the institutions that purportedly contributed to Japanese leadership – e.g., strong bureaucracies, lifetime employment, keiretsu, weak shareholder rights – came under stress and have themselves been the target of major reforms (Reed et al., Reference Reed, McElwain and Shimizu2009; Hoshi and Lipscy, Reference Hoshi and Lipscy2021).

It is also important to emphasize that a harbinger state is not the same as a bellwether state, which can be defined as a state that predicts how others will respond to an issue or challenge. The most effective solutions will not necessarily emerge in a country first confronting a novel challenge. If anything, first-mover status may lead to a slow process of failure and experimentation as a country discovers the shortcomings of existing policy responses and searches for effective solutions (Lipscy and Takinami, Reference Lipscy and Takinami2013). The Japanese government has often tended toward cautious experimentation and muddling through rather than decisive solutions. Nonetheless, the harbinger's policy response will offer important lessons for other states confronting the same challenge with a lag. For scholars, studying the politics of the harbinger state will be informative for understanding the nature and emerging pattern of political contestation in other countries.

Of course, Japan is not a harbinger across all issue areas. It would be absurd to claim Japan is a step ahead of other countries in the politics of gender equality or space policy (Pekkanen and Kallender-Umezu, Reference Pekkanen and Kallender-Umezu2010; Steel, Reference Steel2019). In other cases, Japan has confronted global challenges in tandem with other countries, such as the 1970s oil shocks (Ikenberry, Reference Ikenberry1986; Meckling et al., Reference Meckling, Lipscy, Finnegan and Metz2022). In yet other areas – such as the management of compensatory policies and protests – the country may exhibit at least some patterns of political interaction that are relatively unique (Pharr, Reference Pharr1990; Calder, Reference Calder1991). In what follows, I will briefly survey three broad areas in which Japan has confronted some issues early and thus can be plausibly described as a harbinger state. The list is neither meant to be definitive nor comprehensive. I will also consider some of the reasons why Japan is a step ahead of other countries in some issues but not in others.

4.1 Economic transformation

The most widely studied domain of Japan as a harbinger is perhaps its two economic transitions: the growth miracle that catapulted the country to one of the largest economies of the world and the long stagnation that followed the bursting of asset price bubbles in 1991. During both transitions, Japanese economic policies attracted widespread scholarly attention, inspiring voluminous literatures on the sources of rapid economic growth for late-developing countries, relationship between the government and private sector, and the challenges of deflationary financial crises and stagnation.

Japan was not the first country to industrialize, but it was the first to do so outside of the West as a late-developing country. Japan's efforts to manage rapid, catch-up development thus became a topic of considerable interest and spawned academic literatures that contributed theoretical insights to a variety of subsequent scholarship. Early scholarship about the developmental state and industrial policy generated theoretical ideas rooted in careful study of Japan (Johnson, Reference Johnson1982; Samuels, Reference Samuels1987; Okimoto, Reference Okimoto1990). This literature significantly influenced subsequent work on late development and growth miracles (Amsden, Reference Amsden1992; World Bank, 1993; Rowen, Reference Rowen1998; Oi, Reference Oi1999; Doner et al., Reference Doner, Ritchie and Slater2005). In the policy domain, the governments of many developing countries, particularly those in East and Southeast Asia, sought to learn and adapt lessons from Japan's export-oriented developmental strategy (Haggard, Reference Haggard1990; Amsden, Reference Amsden2001). Theoretical approaches developed from careful study of Japanese economic institutions during this era shaped literatures that remain widely influential to this day. For example, Masahiko Aoki's pioneering game theoretic work on institutional complementarities in Japan was incorporated as a foundational feature of the varieties of capitalism (Aoki, Reference Aoki1988; Hall and Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001).

Similarly, Japan's economic difficulties after the 1990s were not the first example of a financial crisis or abrupt growth slowdown. However, the deflationary stagnation Japan experienced introduced new policy challenges – such as a liquidity trap and the zero lower bound of interest rates – that could not be resolved using conventional macroeconomic policy responses. Studies of Japan's stagnation began as a largely country-specific exercise, but the insights gained directly shaped subsequent academic debates about the political economy of financial crises in advanced industrialized countries (Bernanke, Reference Bernanke, Posen and Mikitani2000; Grimes, Reference Grimes2002; Hoshi and Kashyap, Reference Hoshi and Kashyap2004, Reference Hoshi and Kashyap2010; Amyx, Reference Amyx2006; Katada, Reference Katada2006; Park et al., Reference Park, Kojo, Chiozza and Katada2018). The US response to the 2008 subprime crisis drew directly on perceived lessons by policymakers who had either studied or helped managed the Japanese crisis, such as Ben Bernanke, Timothy Geithner, and Lawrence Summers. Compared to the Japanese response, which was characterized by a slow process of failure, experimentation, and discovery of novel policy solutions, the US response was characterized by the rapid application of the most successful Japanese policy measures (Lipscy and Takinami, Reference Lipscy and Takinami2013). Policy tools developed in Japan – particularly unconventional monetary policy measures such as zero interest rates and quantitative easing – came into widespread use across the globe.

Japan's status as a harbinger in a macroeconomic sense largely appears to be a thing of the past. In recent years, Japan's economy does not stand out for rapid growth or stagnation in the aggregate: on a per capita GDP basis, the Japanese economy is now growing at roughly the same rate as other advanced industrialized countries (Figure 3). This reflects the Japanification of other industrialized countries, with ‘secular stagnation’ setting in after the 2008 financial crisis, as well as the modestly improved macroeconomic performance of Japan during a period that roughly corresponds to the tenure of the Abe government and Abenomics reforms (Hoshi and Lipscy, Reference Hoshi and Lipscy2021).

Figure 3. Difference in GDP per capita growth rate (nominal, %), Japan vs average of high-income countries.

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Nonetheless, there are related areas where Japan still remains ahead of the curve in confronting economic challenges and thus worthy of continued attention from political economy scholars. Japan's early efforts to counteract secular stagnation through fiscal policy measures catapulted its public debt burden to a level second to none, but predictions of a major crisis have repeatedly fallen flat (Bamba and Weinstein, Reference Bamba, Weinstein, Lipscy and Hoshi2021). Other advanced industrialized countries are not far behind, especially after large fiscal outlays in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Important, existing scholarship on Japanese fiscal policy and pork barrel politics has contributed theoretical insights to the broader literature (Patterson and Beason, Reference Patterson and Beason2001; Scheiner, Reference Scheiner2005; Catalinac et al., Reference Catalinac, de Mesquita and Smith2020). Nonetheless, Japan as a harbinger for the politics of large public debt burdens, their management, and debates over austerity is an area ripe for further research (Bailey and Shibata, Reference Bailey and Shibata2019).

4.2 Demographic and societal transformation

Setting aside the vicissitudes of macroeconomic growth, Japan is also at the forefront of a variety of demographic and societal transformations with significant political consequences. Perhaps the most obvious of these is an accelerated demographic transition (Kaizuka and Krueger, Reference Kaizuka and Krueger2006). The share of the 65+ population in Japan is now almost 30%, by far the highest level in the world. However, other countries are not too far behind, as shown in Figure 4: within several decades, many major economies will reach contemporary Japanese levels of aging. Studies about Japan are thus well positioned to inform emerging debates about the impact of aging on a variety of salient dependent variables such as representation and democratic institutions, policymaking in the context of high and increasing public debt burdens, support for economic openness, support for militarized conflict, and redistributive politics between the old and the young (Kweon and Choi, Reference Kweon and Choi2021).

Figure 4. Share of population aged 65+, current and projected.

Source: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (Population Dynamics), World Population Prospects 2019. Projections are based on medium variant.

There are also a wide variety of social trends that were originally reported as cultural curiosities unique to Japan only to emerge with a lag in other countries: the inability of youth to achieve financial independence from their parents and associated social isolation popularized by terms such as parasite single and hikikomori (Saito, Reference Saito1998; Yamada, Reference Yamada1999); widespread loss of interest in marriage and sex described by soshokukei and zesshokukei (Fukasawa, Reference Fukasawa2009); the social isolation of elderly citizens and their communities described by kodokushi, kasoshuraku (Kanno, Reference Kanno2017); and rising crime committed by economically marginalized elderly members of society (koreisha hanzai) (Takayama, Reference Takayama2014). Many of these social trends can be attributed in part to Japan's early shift into economic stagnation and rapid aging compared to other countries. The politics surrounding these issues is ripe for early investigation in the Japanese context as they are already emerging in analogous forms across a variety of other societies.

4.3 International relations transformation

Japan has also been at the forefront of responding to transformative changes in the international order and emerging international relations challenges. Japan was the most prominent rising power in the second half of the twentieth century, ascending from postwar devastation to become the second largest economy in the world. Despite widespread predictions by scholars in the realist tradition that Japan would militarize and pursue confrontation with the USA, Japan's rise has been characterized by peaceful diplomacy and efforts to elevate the country's influence and status through the renegotiation of international agreements and organizations (Waltz, Reference Waltz1993; Lipscy and Tamaki, Reference Lipscy and Tamaki2022). This reflects both domestic policy and transformational changes in the international system that on the one hand dramatically increased the costs of militarized conflict and on the other hand created avenues for countries to elevate their influence and status peacefully. As the first major state to rise within the context of these transformative changes to the international order, Japan's experience holds important lessons for other states.

Japan has also been at the forefront of several international relations challenges associated with the increasing emergence of Asia as the center of global economic activity and geopolitical contestation. Japan was the first Asian country to face US mercantilist pressures and strongarming in the 1980s over concerns about its export-oriented policies and perceived unfair trade practices (Schoppa, Reference Schoppa1993). Such pressure subsequently spread to a variety of other countries, and especially intensified during the Trump administration. Japan's perceived failures in its response to US mercantilist pressures, such as the Plaza Accord, are often mentioned by policymakers in the region as errors to avoid. Japanese firms were also compelled to respond relatively early on to the rise of both peer competitors and complex supply chains in Asia, which emerged as a major political issue as kudoka (industrial hollowing out) after the 1980s.

Furthermore, Japan has been at the forefront of responding to the geopolitical rise of China, which is now seen by many Japanese policymakers as the country's principal national security challenge (Liff, Reference Liff2019). Chinese military spending eclipsed that of Japan in the 2000s, and Japanese public sentiment toward China soured along with increasing geopolitical and economic competition and mounting tensions over territorial and historical disputes. For much of the 2000s–2010s, there was a gap between the threat perception toward China of the Japanese government and Western counterparts, which led to considerable anxiety and Japanese efforts to counter Chinese influence through a geoeconomics strategy and initiatives such as the Quad, Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy, and Quality Infrastructure (Hosoya, Reference Hosoya2019; Katada, Reference Katada2020). However, as China's rise continues and its geopolitical and economic influence extends beyond Asia, governments in the rest of the world also began to perceive China as a serious geopolitical threat. Aside from elite opinion, public opinion polling on unfavorable views toward China also shows a pattern of early Japanese souring and subsequent global convergence toward Japanese levels (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Percent polled who have an unfavorable view of China.

Source: Silver et al. (Reference Silver, Devlin and Huang2020).

Finally, although on a much shorter timescale, Japan arguably played the role of harbinger for developed democracies in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic originated in China, but Japan was one of the first advanced industrialized democracies to experience contagion, and early coverage of the pandemic was briefly dominated by Japan's response to the outbreak aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship. The scientific evidence Japanese experts and policymakers obtained about the SARS-CoV-2 virus from this early experience, particularly about the likely aerosol transmission of the virus, was used to formulate several distinct features of Japan's response – the 3Cs (avoidance of crowded places, close-contact settings, and confined and enclosed spaces), retrospective contract tracing, and the public distribution of masks (Asia Pacific Initiative, 2020). These measures, which ultimately proved prescient, informed the responses in other countries as the pandemic spread more broadly, though to varying degrees and with a considerable lag in some cases.

5. Where and why is Japan a harbinger state?

Japan's position as a country one step ahead of others likely reflects the confluence of several factors. Although this is in no way intended to be a comprehensive list, three factors seem to stand out: selective openness to change, geographic location, and constitutional and normative constraints. It is worth repeating that Japan is not a harbinger states for all issues. Several of these characteristics also likely contribute to Japan being considerably behind other countries in specific issue areas.

First, to some extent, Japan's status as a harbinger likely reflects a selective openness to change. Japan's management of its rapid economic growth after World War II inspired many developing countries in part because Japan's developmental model adopted aspects of Western capitalism while maintaining distinctly Japanese institutional foundations. Japan's experience contributed to a shift away from naïve, ‘one-size-fits-all’ strategies among developmental economists in favor of adapting core principles to local institutions and conditions (Rodrik, Reference Rodrik, Aghion and Durlauf2005).

Similarly, an important trigger for the long stagnation after the bubble years was financial liberalization coupled with insufficient adaptation of traditional, informal regulatory structures (Amyx, Reference Amyx2006). Demographic decline in part reflects the rapid transformation of Japanese society as a result of economic development on the one hand and the slow pace of the political system in making legal, institutional, and normative adjustments necessary to promote gender equity, adequate childcare, and work–life balance (Rosenbluth, Reference Rosenbluth2006). This gap between economic and social change on the one hand and governing institutions is not unique to Japan, which is why the country can be plausibly described as a harbinger. However, the gap emerged early and grew particularly wide because of the rapidity of Japan's economic transformation coupled with lagging institutional change. The slow pace of political adjustment to economic and societal shifts contributes to Japan's status as a laggard in areas such as gender equality, minority rights, and immigration (Chung, Reference Chung2010; Strausz, Reference Strausz2019).

Second, Japan's geographic location also likely plays a role. Japan is a leading country in a part of the world that is at the forefront of both geopolitical competition and economic dynamism. Japan is thus affected relatively early by trends and challenges that emerge in the region. Japanese defense planners reacted early and sounded the alarm to the geopolitical challenge presented by China in part because of geographic proximity. Japan was also early in integrating into and managing value chains in the region, which came to occupy a central place in the global economy. Albeit on a shorter timescale, Japan also likely encountered the COVID-19 pandemic early due to large travel volumes vis-à-vis China, which can be attributed in part to regional proximity and economic integration. Japan's geographic location also likely contributes to its status as a laggard in some areas. Japan's slow response to climate change (Aldrich et al., Reference Aldrich, Lipscy and McCarthy2019; Incerti and Lipscy, Reference Incerti, Lipscy, Hancock and Allison2020) may have been more proactive if the country was subject to peer pressure as a member of the European Union or shared a land border with a resource-rich country, which would give it more options to manage energy security challenges.

Finally, Japan's distinct constitutional and normative constraints may play some role in compelling Japan to pursue policy trajectories that other countries only arrive at later. Japan's peaceful rise in the postwar order, which defied realist predictions of militarization and confrontation with the USA, was shaped by constraints imposed by Article 9 and postwar pacifism but also demonstrated to other countries that a nonviolent route to international prominence was feasible. During the COVID-19 pandemic, domestic constraints on legally enforceable lockdown orders compelled Japanese policymakers to develop an approach that did not sharply restrict personal liberties, contributing to innovations such as retrospective contact tracing and an early adoption of the 3Cs that came to be adopted worldwide (Lipscy, Reference Lipscy, Pekkanen, Reed and Smith2023). Of course, these constraints also put Japan behind in areas where other countries enjoy flexibility, most obviously in the acquisition and development of military capabilities. It is also worth noting that being a laggard is not necessarily a bad thing: one could argue that domestic institutional constraints have forestalled Japan from becoming a harbinger of democratic backsliding and populist backlash against the liberal order.

6. Conclusion

There are a variety of reasons why scholars study Japan. None of them is inherently better than the others. It is perfectly reasonable to pursue research on Japan because the country is fascinating and important. However, it is also true that research in the field of political science will have a greater impact if it generates or tests general theories that apply across a wide variety of contexts. Understanding and navigating this tradeoff is an important skill for scholars with expertise in the politics and foreign policy of Japan.

I identified three common approaches to conducting Japan-related research, which can be concisely summarized as (1) Japan-specific; (2) testing general theories using evidence from Japan; and (3) generating general theories from studies of Japan. I then argued that the third approach is relatively neglected and worth of greater attention owing to Japan's status as a harbinger state. Japan's status as a harbinger state in several key issue areas can be leveraged by scholars to develop theories and conduct early empirical tests about political issues that are likely to become generalized in the future. Policymakers can seek lessons from Japan's policy record to understand and prepare for emerging challenges.

The concept of the harbinger state developed here is in no way meant to be exclusive to Japan. I defined a harbinger state as a country that engages in the politics of a particular issue prior to others and included the caveat that being early should not be the result of imposition. Given my premise that studying Japan is useful for developing ideas and theories with wide applicability, it would only be fitting if scholars who specialize in the study of other countries find the concept useful.

I also emphasized that it is important to distinguish between a harbinger, leader, and bellwether. Japan may be early in confronting new challenges, but that does not mean its policy responses are always worthy of emulation or predictive of political outcomes elsewhere. Comparative study of cross-national variation remains essential. Timing may also influence how a country responds to an emerging challenge, as it affects the availability of received wisdom about effective solutions.

The study of Japan in political science remains more robust than ever. This is thanks in large measure to the contributions of Susan Pharr and other scholars of her generation. Scholarship has grown in both quantity and quality. The intellectual community continues to expand, and new initiatives such as the Japanese Politics Online Seminar Series are connecting scholars across geographic boundaries (Catalinac et al., Reference Catalinac, Crabtree, Davis, Fujihira, Horiuchi, Lipscy, Rosenbluth and Smith2022). Studies of Japan in top political science journals have been published at a consistent pace while the volume of publications has increased considerably over the past four decades. The number of top journal publications about Japan remains low in absolute terms, but this reflects idiosyncrasies of the discipline rather than issues specific to Japan: the field has often arbitrarily marginalized non-Western, country-specific studies and topics such as climate change and pandemics as ‘not of general interest.’ The discipline will surely evolve toward a notion of general interest that is less distorted and more attuned to objective reality, but as with all things in the academy, change takes time. In the meantime, Japan remains a fascinating country that will remain an important source of both innovative theory and empirical evidence for the field.

Acknowledgments

I thank Christina Davis, Margarita Estevez-Abe, Timothy George, Rieko Kage, Junko Kato, Kenneth McElwain, Robert Pekkanen, Susan Pharr, Dan Smith, and Hiroki Takeuchi for their helpful feedback. An earlier version of this paper was presented at ‘Japan in the World: A Symposium in Honor of Susan J. Pharr, Edwin O. Reischauer Professor of Japanese Politics,’ Harvard University, 25 May 2021.