Breast-feeding, particularly mother’s own milk, provides tremendous health benefits and nutrients to infants. Current recommendations in the USA include exclusive breast-feeding for the first 6 months of an infant’s life with continued breast-feeding through the first year or longer( 1 ). Breast-feeding initiation rates continue to increase in the USA and more than 80 % of children are ever breast-fed. However, in 2013, the maintenance of exclusive breast-feeding for 6 months (22·3 %) and any breast-feeding for a full year (30·7 %) were below the national Healthy People 2020 objectives of 25·5 and 34·1 %, respectively( 2 ). Considering the health benefits of breast-feeding for longer durations( 1 , Reference Bartick and Reinhold 3 ), this gap between initiation and duration rates highlights a need to provide additional support for mothers to maintain breast-feeding or providing their breast milk.

As posited in Rothman’s theory-based analysis of behavioural maintenance, if an individual is satisfied with the received outcomes of a behaviour or experience, then the behaviour is likely to be maintained( Reference Rothman 4 ). In a study applying this conceptualization to breast-feeding, women who reported initial breast-feeding experiences as negative were less likely to continue( Reference DiGirolamo, Thompson and Martorell 5 ). Similarly, those who were very or fairly dissatisfied with the breast-feeding experience reported a shorter median duration of breast-feeding compared with those who were very or fairly satisfied. Research highlights barriers to the maintenance of breast-feeding including those that are physiological (e.g. pain and difficulty breast-feeding)( Reference Augustin, Donovan and Lozano 6 – Reference Labarere, Gelbert-Baudino and Laborde 10 ) and social (e.g. breast-feeding in public, maternity leave policy)( Reference McInnes, Hoddinott and Britten 11 , Reference Langellier, Chaparro and Whaley 12 ) in nature.

Some women continue to breast-feed, or pump to provide breast milk, despite facing these physiological or social barriers. Studies have shown that maternal perceptions (i.e. attitudes, beliefs, response efficacy, self-efficacy) frequently considered in health behaviour theories such as the Theory of Planned Behaviour( Reference Ajzen 13 ) and the Extended Parallel Process Model( Reference Witte 14 ) have implications for breast-feeding maintenance. Mothers likely hold multiple perceptions about infant feeding stemming from both their own experiences and competing sociocultural ideals( Reference Kaufman, Deenadayalan and Karpati 15 ). In a qualitative study comparing breast-feeding and formula-feeding mothers, those who breast-fed tended to indicate a positive change in breast-feeding beliefs, becoming more pro-breast-feeding, while those who formula-fed their child tended to indicate no change in beliefs about breast-feeding( Reference Cricco-Lizza 16 ). This supports the notion that those holding more positive breast-feeding v. formula-feeding beliefs and attitudes may maintain breast-feeding for longer durations than others( Reference Avery, Duckett and Dodgson 17 ). Similarly, mothers who agree breast-feeding will reduce the baby’s risk for illnesses, showing high levels of response efficacy, are more likely to initiate breast-feeding and maintain exclusive breast-feeding at 2 months compared with those who do not agree( Reference Kornides and Kitsantas 18 ). Breast-feeding self-efficacy, defined as a mother’s belief that she will be able to organize and carry out the necessary actions to breast-feed her child( Reference McCarter-Spaulding and Gore 19 ), has been shown to predict breast-feeding maintenance( Reference Dennis and Faux 20 ). Self-efficacy measured at 1 week postpartum has significantly predicted breast-feeding maintenance at 1 and 6 months postpartum( Reference McCarter-Spaulding and Gore 19 ). It has been suggested that those who continue to breast-feed, despite negative experiences or barriers, may have developed a greater self-efficacy for breast-feeding which decreased the influence of the negative experiences( Reference DiGirolamo, Thompson and Martorell 5 ), perhaps mediating the relationship between barriers to breast-feeding and duration.

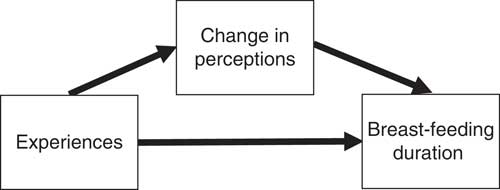

The objective of the present study was to identify factors that may facilitate breast-feeding for longer durations among first-time mothers by considering the roles of physiological experiences, social experiences and changes in maternal perceptions related to breast-feeding or providing breast milk (i.e. breast-feeding self-efficacy, beliefs and opinions about infant feeding options, response efficacy of breast-feeding and satisfaction) as distinct components potentially influencing breast-feeding duration. While previous studies tend to use one-time, prenatal measures of maternal perceptions( Reference Avery, Duckett and Dodgson 17 – Reference Dennis and Faux 20 ), the present study is innovative in the utilization of longitudinal data to explore changes in maternal perceptions occurring during the breast-feeding period that may result from experiences, thereby identifying underlying psychosocial factors that facilitate or deter the maintenance of breast-feeding and providing breast milk. We further hypothesized that changes in maternal perceptions would mediate the relationship between breast-feeding experiences and duration, over and above their prenatal or baseline perceptions (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Hypothesized mediation model

Methods

Longitudinal data in the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (IFPS II) were gathered from women in late pregnancy through their infant’s first year of life between 2005 and 2007 by the US Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention( Reference Fein, Labiner-Wolfe and Shealy 21 ). Data relevant to that study were collected via mailed self-administered questionnaires including a prenatal questionnaire, a neonatal questionnaire when the baby was 1 month old, and nine postnatal questionnaires sent monthly between months 2 and 7 postpartum and then at 7-week intervals until the baby was 12 months old, regardless of breast-feeding status( 22 ). Most variables considered in the current secondary analysis originated in the prenatal or neonatal questionnaires, and module B (module regarding breast-feeding cessation, completed when participants indicated recently stopping breast-feeding and/or pumping) in the postnatal questionnaires.

Participants were recruited via a nationally distributed consumer opinion panel of more than 500 000 households; the final sample consisted of 3033 women who completed the neonatal questionnaire, and 1807 completed all questionnaires( Reference Fein, Labiner-Wolfe and Shealy 21 , 22 ). The current analysis includes data from first-time mothers who indicated ever breast-feeding to eliminate the effect of prior infant feeding experiences( Reference Manstead, Profitt and Smart 23 ). Those who indicated never breast-feeding, had missing data that could not be imputed for whether they were a first-time mother or had ever breast-fed, or indicated having or adopting previous babies, were excluded from analysis. The final study sample of first-time mothers who ever breast-fed was 762 participants.

Measures

Breast-feeding duration

The time to event (breast-feeding cessation), or the number of weeks mothers maintained breast-feeding or pumping to provide breast milk, is the outcome of the present study. In module B, mothers indicated the infant’s age when she completely stopped breast-feeding or pumping. If a mother did not complete module B, time spent in maintenance was estimated as the time of the last completed survey or the midpoint of infant ages when she last indicated she was breast-feeding and the first questionnaire on which she was not breast-feeding. Mothers who stopped breast-feeding during the study period were classified as having reached the event of breast-feeding cessation (1=yes) and those who were still breast-feeding at the last questionnaire completed were classified as not reaching the event of breast-feeding cessation in the study period (0=no).

Experiences cited as reasons for breast-feeding cessation

In module B, mothers who stopped breast-feeding identified how important thirty-two reasons were to their decision (1=‘not at all important’ to 4=‘very important’). Responses to a total of fourteen physiological and six social experiences were dichotomized (1=somewhat or very important and 0=not at all or not very important; see Table 1). Four variables were created by combining highly correlated items (r≥0·45)( Reference Aday and Cornelius 24 ), resulting in eleven physiological and five social experiences considered in analysis.

Table 1 Experiences investigated in the present study of first-time mothers’ breast-feeding maintenance

Changes in perceptions

For each perception considered, the measure on the prenatal or neonatal questionnaire was considered baseline and the measure on later postnatal questionnaires was follow-up. The degree of change for each perception was calculated by subtracting the baseline measure from the last follow-up measure collected. A positive number indicated an increase, a negative number indicated a decrease, and zero indicated no change over time.

Mothers responded to questions regarding breast-feeding satisfaction: ‘How would you say you felt about breast-feeding during the first week you were breast-feeding?’ in the neonatal and ‘How do you feel about the experience of having breast-fed your baby?’ in the postnatal questionnaires (1=‘disliked very much’ to 5=‘liked very much’).

In the neonatal questionnaire, mothers indicated their intended breast-feeding duration and were asked ‘How confident are you that you will be able to breast-feed until the baby is the age you marked?’ (1=‘not at all confident’ to 5=‘very confident’). In postnatal questionnaires for months 2, 5 and 7, mothers were asked how long they intended to continue breast-feeding and their confidence in meeting the intended duration. The last postnatal questionnaire which mothers indicated still breast-feeding and their confidence in meeting the goal was used to calculate change in breast-feeding confidence, or self-efficacy.

At baseline and month 7, mothers indicated how much they agreed/disagreed with four statements measuring response efficacy (1=‘strongly disagree’ to 5=‘strongly agree’): ‘If a baby/child is breast-fed, he or she will be less likely to (get ear infections, get respiratory illness, get diarrhoea, become obese)’. Each item was used independently in the analyses.

At baseline and month 7, mothers were asked: ‘How strongly do you agree or disagree … (Infant formula is as good as breast milk)?’ (1=‘strongly agree’ to 5=‘strongly disagree’). At baseline, mothers were also asked, ‘Which of the following is closest to your opinion? The best way to feed a baby is: (breast-feeding, a mix of both breast-feeding and formula feeding, formula feeding, breast-feeding and formula feeding are equally good ways to feed a baby)’. Then in month 3, they were asked about the best way to feed a 3-month-old baby. To calculate change about breast milk belief and opinion about the best way to feed a baby, a three-level variable was created indicating each type of belief (i.e. 3=breast-feeding, 2=mix of breast-feeding and formula feeding or they are equally good, and 1=formula feeding). Negative overall score indicated views became less pro-breast-feeding over time, zero indicated no change, and positive score indicated views became more pro-breast-feeding.

Maternal age, race, education, employment, marital status and income are commonly considered demographic factors in infant feeding research( Reference Meedya, Fahy and Kable 25 ) and these were measured prenatally in the IFPS II. Most variables were dichotomized due to little variability in the sample: race (1=white, 0=not white), marital status (1=married, 0=not married), education (1=more than high school, 0=high school or less), employment (1=employed by self or other either full- or part-time, 0=not employed) and household income (1=less than median income, 0=median income or more). Maternal age was used as a continuous variable.

Analyses

Participant demographics, breast-feeding duration, experiences and changes in perceptions were examined using descriptive statistics. Using accelerated failure time models based on the Weibull distribution for log-transformed duration times, the effect of physiological/social experiences and changes in maternal perceptions on breast-feeding duration were evaluated, controlling for baseline measures and demographic covariates. The accelerated failure time approach is a type of survival analysis that provides results that can be directly translated into expected reduction or extension of median time to event( Reference Patel, Kay and Rowell 26 ). Exponentiating the regression coefficients provides a direct estimate of the ratio between the breast-feeding duration of two mothers who differ by one unit with respect to that covariate, controlling for the other variables in the model. In the present paper we refer to this estimate as a ‘duration ratio’ (DR). Relationships between physiological and social experiences and changes in maternal perceptions, controlling for baseline measures, were explored using linear regression models. Changes in maternal perceptions significantly associated with both breast-feeding duration and experiences were added to the first model of the subsequent analysis looking at the associations between experiences and duration to explore possible mediation( Reference Baron and Kenny 27 ).

For each set of analyses, bivariate associations were explored. Significant factors were added to multivariate models with no a priori choice of reference variable, and non-significant factors were removed using backward elimination and judgement based on current literature. Analyses were conducted using the statistical software package SAS version 9.4.

Results

Characteristics of the 762 mothers are presented in Table 2. The majority were married (67·4 %), earned more than a high-school education (80·8 %), employed (70·9 %) and white (83·8 %). The mothers’ mean age was 26·7 (sd 5·6) years, and the median household income was between $US 45 000 and $US 49 999 with, on average, 2·5 (sd 1·1) people living in the household.

Table 2 Characteristics of participants: first-time mothers who ever breast-fed (n 762) from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (USA), 2005–2007

† Median household income was $US 45 000–49 999.

As shown in Table 3, at 12 months, 216 mothers (28·4 %) were still breast-feeding, pumping or stopped participating in the study, and are considered censored in the accelerated failure time model. Median breast-feeding duration was 19·4 weeks. Of those who stopped breast-feeding and pumping, physiological and social experiences commonly indicated as important reasons for stopping included: the experience of ‘milk problems’ (57·2 %), trouble sucking or latching (30·9 %) and ‘painful breast-feeding’ (23·1 %). Over time, mean breast-feeding self-efficacy and satisfaction scores increased significantly, indicating more pro-breast-feeding views compared with the baseline scores. However, the mean change scores for opinion about breast-feeding, belief about breast milk and response efficacy regarding protection against respiratory illnesses and diarrhoea decreased significantly over time, indicating that views changed to be less pro-breast-feeding compared with the baseline measures.

Table 3 Description of dependent and independent variables among the first-time mothers who ever breast-fed (n 762) from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (USA), 2005–2007

Change in perception mean is significantly different from baseline: **P<0·01, ***P<0·001.

As shown in Table 4, Model 1, results indicated that for each year increase in maternal age, breast-feeding duration tended to increase by 5 % (DR=1·05). Similarly, those with more than a high-school education or those married breast-fed for longer durations than those with fewer years of education or not married (79 and 54 % longer durations, respectively). Other covariates also considered in the analysis but found to be not significant and excluded were income and employment.

Table 4 Associations of demographics, experiences and change in perceptions with time spent in breast-feeding maintenance among first-time mothers who ever breast-fed (n 762) from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (USA), 2005–2007

DR, duration ratio.

*P<0·05, **P<0·01, ***P<0·001.

As shown in Table 4, Model 2, the experiences significantly associated with reduced breast-feeding duration, controlling for demographic covariates, included trouble with the baby’s suck or latch, overfull or engorged breasts, milk problems and painful experience (57, 41, 27 and 38 % reduction in breast-feeding duration, respectively). The experience of the baby beginning to bite was associated with a longer breast-feeding duration (54 % longer). This observation is likely explained by the fact that teeth emerge later in infancy( 28 ), and thus would only be reported by those who breast-fed to that point. Because it differs from other early experiences and is potentially misleading, experience of biting was not included in later analyses. Social experiences did not remain significant when considered along with physiological factors; the remaining four physiological experiences significantly associated with breast-feeding duration were considered in further analyses.

Considering covariates and baseline measures, each of the changes in maternal perceptions was significantly associated with breast-feeding duration in bivariate analysis. In the multivariate model (Table 4, Model 3), controlling for their baseline measures, changes representing an increase in self-efficacy, pro-breast-feeding opinion and belief about milk v. formula were associated with increases in breast-feeding duration (26, 63 and 31 % longer, respectively). Change in response efficacy with respect to diarrhoea was borderline significant, with a much smaller effect on duration (12 % longer).

The effect of physiological experiences on maternal perceptions adjusting for baseline and demographic covariates is presented in Table 5. Trouble with the baby’s suck or latch and milk problems were significantly associated with a decrease in self-efficacy. Trouble with the baby’s latch, milk problems and painful experiences were significantly associated with decline in pro-breast-feeding opinion. Trouble with the baby’s latch and painful breast-feeding were associated with a decrease in pro-breast-feeding belief. Overfull or engorged breasts were not significantly associated with changes in any of the perceptions evaluated.

Table 5 Associations of demographics, experiences and perceptions associated with changes in maternal breast-feeding perceptions among first-time mothers who ever breast-fed (n 762) from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (USA), 2005–2007

*P<0·05, **P<0·01, ***P<0·001.

The negative effects of physiological experiences on maternal perceptions suggested that it may be useful to break down the effect of experience into its direct and indirect effects, as in Fig. 1. The mediating effect of changes in perceptions is analysed in Table 6. The comparison of Model 1 and Model 2 indicates that changes in self-efficacy, belief and opinion partially mediate the relationship between experiences and breast-feeding duration. In particular, the negative effect of experiencing milk problems is no longer significant in the final model, while the negative effects of trouble with the baby’s suck or latch and pain on breast-feeding duration, while still significant, are smaller in magnitude. For example, as seen in Table 5, perceptions tend to be negatively impacted by negative experiences, which is why we see that the total effect of trouble with a baby’s suck or latch in Table 6, Model 1, representing both its direct effect as well as its indirect effect via maternal perceptions, is a 64 % reduction in duration. However, Table 6, Model 2 indicates that if a woman experiences trouble with a baby’s suck or latch, but her perceptions remain unchanged, this will lead to only a 44 % reduction in breast-feeding duration. Similar reductions are seen for negative experiences with respect to milk problems and pain, although the mediation with respect to pain appears to be rather small.

Table 6 Final model showing associations between demographics, experiences and perceptions and time spent in breast-feeding maintenance among first-time mothers who ever breast-fed (n 762) from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (USA), 2005–2007

DR, duration ratio.

*P<0·05, **P<0·01, ***P<0·001.

Discussion

The primary aim of the present study was to identify factors that may facilitate breast-feeding for longer durations among first-time mothers by examining the relationships between both physiological and social experiences and changes in maternal perceptions during the breast-feeding period. We hypothesized that changes in perceptions would mediate the association between experiences and breast-feeding duration. We demonstrated quantitatively and longitudinally that maternal perceptions (e.g. self-efficacy, opinions and beliefs) change over time and these changes are significantly associated with breast-feeding duration. Furthermore, the effect of negative physiological experiences on breast-feeding duration appears to be partially mediated by these changes in maternal perception.

Mothers’ perceptions likely change many times throughout the breast-feeding experience. While we were unable to measure each instance of change in relation to experiences, the present study is unique in its evaluation of changes between prenatal and postnatal measures of perceptions, rather than only considering perceptions measured prenatally or at baseline. Findings indicate that increases towards stronger pro-breast-feeding opinion and belief, and increase in breast-feeding self-efficacy tend to increase breast-feeding duration. Conversely, negative physiological experiences tend to decrease these beliefs, leading to substantial decreases in breast-feeding duration on top of the direct impact of those experiences. These findings emphasize the importance of assessing mothers’ perceptions regarding breast-feeding and feeding breast milk after they initiate, on an ongoing basis, to enhance our understanding of infant feeding behaviour and breast-feeding duration. We may be able to address the gap between high breast-feeding initiation rate and short duration by facilitating positive changes and minimizing negative changes in mothers’ perceptions at opportune times. While both prenatal and postnatal support and education improve maternal perceptions and the rates of breast-feeding maintenance, postnatal support alone has been shown to be slightly more effective than prenatal education in extending breast-feeding duration( Reference Lin-Lin, Yap-Seng and Yiong-Huak 29 ). The present study showed that perceptions of self-efficacy, opinions and beliefs change over time, suggesting the type of support needed may also change. Thus, it may be plausible to mitigate barriers and facilitate positive changes in perceptions, towards a more pro-breast-feeding view, through ongoing, systematic postnatal interventions that can be tailored to mothers’ experiences.

The current study showed that both physiological and social experiences cited as reasons to stop breast-feeding are associated with breast-feeding duration; however, when considered together, social experiences did not remain significant, suggesting the physiological experiences may have greater implications for mothers maintaining breast-feeding. However, the physiological experiences need to be considered within mothers’ social contexts. For example, mothers returning to work may experience trouble with pumping or milk flow/supply; however, provision of breast milk is likely to be maintained if the workplace supports, protects and promotes breast-feeding( Reference Abdulwadud and Snow 30 ). Similarly, breast and nipple pain is often associated with suboptimal positioning and latch( Reference Berens 31 ). Social factors such as support and early attention from health-care providers or experienced support providers to confirm correct positioning may help prevent these problems( Reference Berens 31 ). Painful breast-feeding or trouble with the baby’s latch may come as a surprise to mothers who anticipated breast-feeding to be an easy or natural process( Reference Kelleher 32 ). This unexpected pain and trouble likely happens early, in the first few days and weeks of breast-feeding, and may be a stressor leading to hesitation or anxiety with breast-feeding caused by the anticipation of pain and physical vulnerability( Reference Kelleher 32 ), which may decrease breast-feeding self-efficacy and opinion about breast-feeding. Our results suggest we may be able to break the cycle of negative experiences decreasing breast-feeding perceptions and decreasing duration through interventions addressing sources of these experiences early and promoting positive increases in breast-feeding perceptions.

While breast-feeding is an enjoyable experience for some, many mothers do not feel prepared for the contrast between ideal breast-feeding and reality where breast-feeding is met with difficulties( Reference Kelleher 32 ); thus, the experience does not always match their expectation. The observed changes in breast-feeding self-efficacy, opinion and belief becoming less pro-breast-feeding in the present study may partly be explained by this unmatched expectation and reality. Future research should explore possible methods for reducing the gap between ideal and realistic breast-feeding experiences, and ensure early breast-feeding success, by continuing to equip mothers with effective knowledge and skills to initiate and troubleshooting and coping skills to maintain breast-feeding.

Previous studies have shown the importance of support from family( Reference Ingram and Johnson 33 ), peers( Reference Arlotti, Cottrell and Lee 34 ) and health-care professionals( Reference Renfrew, McCormick and Wade 35 ) in helping mothers continue breast-feeding. However, given that 81 % of mothers initiate breast-feeding in the USA, but a significantly smaller proportion (about 31 %) maintains for at least a full year or longer( 2 ), we need to continue exploring cost-effective ways to provide ongoing support to breast-feeding mothers after they have left the hospital and breast-feeding has been established. Having a health-care provider involved in follow-up support with breast-feeding mothers is known to be associated with increased breast-feeding duration( Reference Taveras, Capra and Braveman 36 , Reference Labarere, Gelbert-Baudino and Ayral 37 ). Systems providing proactive support and ongoing education prenatally and in the weeks and months following birth are likely to be more effective than if mothers are expected to reach out for help on their own( Reference Renfrew, McCormick and Wade 35 , Reference Tedder 38 ). Results from our study help to narrow the focus of these support interventions to address perceptions that may arise from early breast-feeding experiences. Theory-based programmes to address these perceptions and methods to increase the accessibility and systematic delivery of breast-feeding support from health-care providers after mothers have left the hospital should be investigated further.

Limitations

Results may not be generalized to the overall population due to selection, social desirability and recall( Reference Fein, Labiner-Wolfe and Shealy 21 ) biases. The present study participants were more likely to be white, married and have higher education levels than the general population of first-time mothers. This demographic group has been shown to breast-feed for a longer duration, on average, than other groups (e.g. African American, unmarried mothers)( Reference Meedya, Fahy and Kable 25 , Reference Chin, Myers and Magnus 39 ). However, whether other demographic groups experience similar changes in perception over time, and the impact of these changes on breast-feeding duration, is unknown. Future longitudinal studies would benefit from more demographic variability, which would enable researchers to investigate whether the changes observed in the present study are similar across different subgroups of women. This information would help to tailor interventions to meet the needs of differing subgroups. Also, as in any study without a prespecified model, the use of the same data to both select a model and estimate model parameters may introduce bias.

A wave system was used in data collection and follow-up measures of perceptions did not occur at the same time mothers encountered physiological experiences; thus, some of the change scores represented change over shorter time periods than other measures. It could be that a mother experienced pain and stopped breast-feeding a few weeks before completing the next survey measuring her perceptions. Similarly, the experiences were measured only among mothers who stopped breast-feeding and cited the experiences as reasons for stopping. It is possible that mothers who continued breast-feeding beyond the study period encountered similar experiences, but they did not respond to questions about their breast-feeding cessation.

Conclusion

The present study identified underlying experiences and changes in maternal perceptions that may respectively hinder or facilitate the maintenance of breast-feeding among first-time mothers. As anticipated from Rothman’s concept of behavioural maintenance( Reference Rothman 4 ), those experiencing problems with latch, milk flow/supply and pain were likely to cite them as reasons to stop breast-feeding sooner than mothers who did not experience these factors or consider them to be important reasons for stopping breast-feeding. However, increases in breast-feeding self-efficacy, and favourable opinions about breast-feeding and beliefs about breast milk, were associated with increases in breast-feeding duration and maintaining these perceptions mitigated the negative impact of early breast-feeding problems on duration. These findings provide insight into public health implications in the development and evaluation of breast-feeding interventions for postpartum mothers. Considering that mothers’ perceptions of breast-feeding self-efficacy, belief about breast milk and opinion about breast-feeding can change over time and positive changes can help reduce negative effects of experiencing trouble with suck/latch and painful breast-feeding, future research and interventions should explore the best ways to continually monitor and positively influence these factors. An ongoing, systematic approach to interventions targeting prominent factors identified in the present study, both before and after initiation, may help improve breast-feeding perceptions and decrease the overall negative impacts of experiences, effectively increasing breast-feeding duration.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to acknowledge Dr Laura Schwab-Reese for her assistance with survival analysis methods and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for sharing the IFPS II data. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: E.J.S. conceived of and conducted the study and wrote the article. S.C., T.T.C., P.J.M., P.B. and S.A. were instrumental in providing assistance with theoretical components, data analysis and article preparation. Ethics of human subject participation: The Institutional Review Board at the University of Iowa determined that the study, which used de-identified secondary data, was not human subjects research.