In September 2012, european_douchebag posted a photo to r/funny of a Sikh woman with untrimmed facial hair. R/funny is a large community on the social media platform Reddit—at the time, it had over 2.5 million members and european_douchebag’s original thread garnered over 1,500 comments. While many of the responses were relatively derogatory to start, the tone of the conversation soon shifted; commenters began to shame european_douchebag for making fun of the woman pictured. Later, the photo’s subject responded directly to the post, bringing national media attention to the incident (The Huffington Post 2012). Five days after that, european_douchebag deleted his account. Echoing the sentiments of other subjects of high-profile online public shaming (OPS), european_douchebag highlighted the vitriol and relentlessness of responses to his relatively low-stakes norm violation: “Being constantly reminded of a stupid post I made is kinda awful,” he wrote. “And all the people telling me I should kill myself and that im (sic) a terrible person is pretty bad too… I’m just a normal dude who made a dumb mistake that has led to a viral internet sensation” (european_douchebag 2012b).

European_douchebag is not unique in his experience of public shaming. “Thanks to the internet,” as comedian John Oliver put it in 2019, public shaming has become “one of America’s favorite past times” (The Guardian 2019). And while some argue that OPS can be an effective tool for accountability (Berndt Rasmussen and Yaouzis Reference Berndt Rasmussen and Yaouzis2020; Skoric et al. Reference Skoric, Chua, Liew, Wong and Yeo2010; Wall and Williams Reference Wall and Williams2007)—one often wielded by the relatively powerless who are otherwise largely locked out of public discourse (Clark Reference Clark2020)—the majority of scholars and journalists tend to agree that OPS is “widespread, dangerous, and continually increasing” (Muir, Roberts, and Sheridan Reference Muir, Roberts and Sheridan2021, 2–5).

Specific criticisms of OPS vary. Some point to the ways that OPS often involves serious infringements on the privacy and dignity of its targets (Cheung Reference Cheung2014; Laidlaw Reference Laidlaw2017). Others argue that it turns average users into “Harmless Torturers” who can “easily swarm the weak” (Bloom and Jordan Reference Bloom and Jordan2018). As a result, some argue, OPS creates an “online hate storm” that destroys lives and reputations (Daly Reference Daly2015) and leaves targets with “permanent digital baggage” (Solove Reference Solove2008, 93). Often, as in european_douchebag’s case, OPS is understood to be a disproportionate response to social norm violations—one that lacks due process for the shamed and accountability for the shamers (Billingham and Parr Reference Billingham and Parr2020b). Taken together, as Aitchinson and Meckled-Garcia (Reference Aitchinson and Meckled-Garcia2021, 3) conclude, it seems clear that OPS is a “moral wrong and social ill.”

Some of the critiques of OPS—for example, that it is a “failure of fundamental respect” (Aitchinson and Meckled-Garcia Reference Aitchinson and Meckled-Garcia2021, 15)—echo longstanding criticisms of public shaming, more generally (see Nussbaum Reference Nussbaum2004). But, as scholars like Harrison Frye (Reference Frye2022) persuasively argue, there are also unique challenges to public shaming in digital environments—like the unprecedented scale introduced by social media. By “increasing the number of individuals who can act in the name of enforcing a norm,” argues Frye, social media incentivize certain pathologies of norm enforcement “including disproportionate treatment, increased error, and alienation” (193). The “inexpensive, anonymous, instant, and easily accessible communication technology” of the internet, as Klonick (Reference Klonick2019) puts it, “has removed natural limits on shaming” (1032). Social media’s massive scale, these scholars argue, makes OPS more likely to be pathological than productive—an experience of harassment, domination, and alienation instead of a form of integrative social accountability.

But while this may be true in some cases, attributing the pathologies of OPS to scale alone risks overlooking other important factors at play. In european_douchebag’s case, for example, though the shaming ultimately developed these pathologies, it did not begin with them. In fact, one day prior to deleting his account, european_douchebag had apologized “to the Sikhs, [the woman pictured], and anyone else I offended,” acknowledging that his original post “was an incredibly rude, judgmental, and ignorant thing to post” (european_douchebag 2012a). This apology was largely accepted by the r/funny community, as posters noted it was “cool” that european_douchebag had admitted his mistake and thanked him for apologizing. And it seems that he did accept responsibility—and attempt to atone—for his original norm violation. In explaining his decision to delete his account, european_douchebag acknowledged the corrective effective of the shaming: “This whole ordeal has definitely impacted my life for the better,” he began, before closing by insisting that he was “glad so much positive stuff came from a negative post. Seriously” (european_douchebag 2012b). European_douchebag’s experience with OPS thus challenges how scholars commonly understand the practice. Before his shaming turned pathological, before he was harassed off Reddit, it seems european_douchebag’s public shaming was productive—it not only reinforced r/funny’s norms around appropriate posting, but also induced european_douchebag to reevaluate and change his behavior, bringing it in line with r/funny’s expectations. How can we explain this seeming contradiction?

Some, like Jacquet (Reference Jacquet2015), have suggested ways that differences in context can contribute to OPS’s success or failure. There are, after all, examples—like Greenpeace’s sustainable supermarkets rankings—where large-scale public shaming is not just productive but also perhaps the only option for accountability in the face of little legal recourse. Thus, it seems that large-scale OPS need not always result in the pathologies scholars like Frye and Klonick warn of. Indeed, as Jacquet argues, there may be several factors—like the kind of norm violation and the frequency with which shaming is used—that might contribute to “highly effective” shamings, even in large-scale online environments.

In this article, I propose an additional variable to consider when evaluating the efficacy of OPS. Alongside factors like scale, substance, and frequency, I argue, the network structure of OPS—meaning the pattern of relationships between those involved—also contributes to rendering these informal sanctioning practices productive or pathological. Instead of tracing the limitations of OPS to a “mob mentality” cultivated solely by social media’s mass scale, I focus on the interpersonal contexts within which OPS occurs and the ways that certain social media platforms facilitate network structures more conducive to productive OPS. In evaluating OPS by way of network structure, I argue, we can not only better understand why OPS works productively in some cases and not in others, but also derive lessons for how to deploy, discuss, and respond to it more effectively.

Whereas scale highlights the number of people involved in any given social network, structure emphasizes the relationships between the members involved in it. While network structure can be characterized in several ways, in this article I highlight the importance of network transitivity, or interconnectedness: specifically, the difference between open and closed network structures.Footnote 1 In closed networks, individuals have more shared connections with one another. In open networks, by contrast, there are fewer connections between individuals. And while scale can certainly influence structure—since smaller networks are more likely to be more highly transitive, or interconnected—they are conceptually distinct. Institutions, like membership organizations or states, can help to close large-scale networks (Coleman Reference Coleman1993), as can certain elements of the built environment (Forestal Reference Forestal2022). So while scale can have the deleterious effects on public shaming that scholars describe, it need not have to; as I will suggest, there are certain design elements that online platforms might employ to mitigate some pathologies of scale, while potentially retaining OPS as a productive social sanctioning practice.

In what follows, I argue that productive shaming is more likely to occur within a closed network structure. While empirical scholars have identified three social conditions necessary for public shaming to operate productively as a mechanism of social control—the (1) recognition of the shamer’s authority to sanction shared norms, (2) presence of reputational considerations for the shamed, and (3) possibility that the shamed will be reintegrated into the community, post-shaming—they have not yet explored the ways that closed networks help to facilitate these conditions.

After first outlining the relationship between closed networks and productive shaming, I then use this conceptual framework to show how social media platforms like Twitter and Wikipedia facilitate different network structures among users, with different results for OPS. Twitter, with its open social network structure, leads OPS on the platform to often devolve into pathological “piling on.” Wikipedia, by contrast, facilitates a closed network that makes it easier to deploy OPS techniques without these pathologies. I conclude by returning to the example of european_douchebag and Reddit to show how using the analytic lens of network structure can help us better understand the conditions under which OPS can remain productive and identify more effective strategies to mitigate its pathologies.

NETWORK STRUCTURE, SHAME, AND SOCIAL CONTROL

Democracy requires social norms. A shared set of norms—like reciprocity, cooperation, and conflict resolution—provide conditions under which citizens can work together to hold one another accountable and engage in the democratic practices of collective problem-solving (Van Schoelandt Reference Van Schoelandt2018). But in order for social norms to serve this function, they must be enforced (Ellickson Reference Ellickson1994). Indeed, it is only through enforcement—whether positive or negative—that norms gain their power. In modern mass democracies, this enforcement is often the responsibility of formal institutions, like the police. Yet unlike with laws, and the formal actors who enforce them, many other democratic norms are informal (e.g., Blajer de la Garza Reference Blajer de la Garza2019); in these cases, sanctioning is likewise conducted informally—by citizens on other citizens.

Informal social sanctions can take many forms, including public shaming. As “a practice of public moral criticism in response to violations of social norms” (Billingham and Parr Reference Billingham and Parr2020a, 997), the goal of public shaming is twofold. First, public shaming “motivates individuals to accept responsibility and take reparative action in the wake of” violating social norms (Tangney, Stuewig, and Mashek Reference Tangney, Stuewig and Mashek2007, 355); it also deters future norm violations by others (Finnemore and Hollis Reference Finnemore and Hollis2020; Krain Reference Krain2012). Productive public shaming, then, consists in reinforcing the norm in question on both an individual and collective level. By facilitating a critical self-awareness through which one comes to evaluate their actions through the eyes of their co-citizens (Rawls Reference Rawls1971), public shaming can be a powerful motivator for individuals to acknowledge their norm violation and correct their behavior. And because it consists of citizens holding one another to account, even—and especially—in cases where there is no recourse to formal authority (Etzioni Reference Etzioni2001), this horizontal sanctioning can be a salient reminder to the community of the importance of shared norms and the expectation that violations will be sanctioned. Indeed, as Tarnopolsky (Reference Tarnopolsky2010) points out, there is a long tradition of democratic communities turning to public shaming as a valuable, though informal, mechanism for expressing and enforcing the shared social norms grounding collective life.

That public shaming works as an effective method of social control is evident from empirical research. Scholars have found that aversion to shame is a powerful motivator for contributing to public goods (Kropf and Knack Reference Kropf and Knack2003; Samek and Sheremeta Reference Samek and Sheremeta2014). Likewise, there is compelling evidence that social pressures—including the threat of sanctions like public shaming—effectively induce people to engage in pro-social behaviors like political participation (Knack Reference Knack1992; Panagopoulos Reference Panagopoulos2010) even when those pressures are mediated by social media platforms like Facebook (Bond et al. Reference Bond, Fariss, Jones, Kramer, Marlow, Settle and Fowler2012).

But not all agree that public shaming—however effective—is desirable.Footnote 2 Critics of public shaming contend that the practice is inadequate for its intended purpose (Locke Reference Locke2016). Some argue that it is an undesirable form of mob rule (Whitman Reference Whitman1998), while others note that the practice is largely unreliable, as public shaming campaigns can often “misfire”—targeting innocent bystanders rather than focusing attention on the offender alone (Posner Reference Posner2000). Ultimately, goes this line of thinking, public shaming is an “assault on human dignity” (Nussbaum Reference Nussbaum2004, 4) wholly at odds with the principle of equal respect that grounds democratic society (Markel Reference Markel2001). And, indeed, the fragility of public shaming’s pro-social effects is evident in empirical research. In certain social contexts, public shaming can backfire; rather than mobilize feelings of recognition and repair, it can lead to disengagement that drives bad behavior “underground” (Murphy and Kiffin-Petersen Reference Murphy and Kiffin-Petersen2017).

In parsing these different outcomes, scholars have identified several conditions necessary for public shaming to be a productive mechanism of social sanction—meaning one which facilitates both pro-social behavioral changes and norm reinforcement. There must be (1) recognition, from all involved, of the shamer’s authority to sanction the shamed for violating shared norms. In addition, (2) the reputational considerations of shaming must be salient for the target of shaming. Finally, there must exist (3) the possibility that the shamed will be reintegrated into the community, post-shaming. These three elements of the social context are important considerations in determining public shaming’s efficacy. But while scholars have largely discussed these social conditions separately, in this section, I argue that they are more likely to obtain when there exists a certain social network structure between participants. In particular, I argue that public shaming is more likely to be productive within what the sociologist James Coleman calls a closed “social structure,” or network.

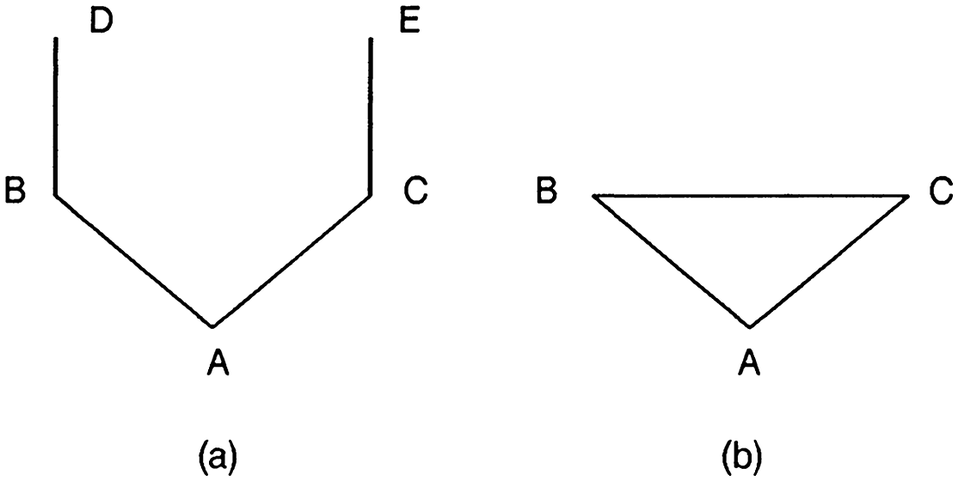

Closure, in Coleman’s understanding, refers to “the frequency of communication between two actors for whom another actor’s action has externalities in the same direction” (Coleman Reference Coleman1990a, 285). The more connections, and lines of communication, there are among members of a group, the more closed the network is—the fewer connections, the more open. Figure 1a (from Coleman Reference Coleman1988) is an open network; while B and C are both affected by A’s actions, there is no connection (or communication) between them. As a result, they will find it difficult to coordinate with one another to sanction A for her actions. In Figure 1b, by contrast, B and C have an existing relationship and thus a way to communicate with one another; sanctioning is much easier, and therefore more likely, because of this closed network structure. The “closure of the social structure” (Coleman Reference Coleman1988, 105–6) thus contributes to social sanctioning—like public shaming—serving as a productive form of social control.

Figure 1. Network Without (A) and With (B) Closure

Source: Image reproduced with permission from Coleman (Reference Coleman1988).

Consider the difference between a neighborhood with frequent block parties and an active list-serv and a neighborhood without these institutions. Within the former, neighbors are more likely to know one another; there are multiple opportunities for them to interact and communicate. Information regarding one neighbor’s misbehavior will therefore likely spread more quickly among the others. By contrast, within the latter neighborhood, the network structure is more open; while individual neighbors might have ties to one another, it is not necessarily the case that one’s ties will overlap with others’—there are likely fewer shared connections within the larger group. It is in the kind of closed network structure that characterizes the former neighborhood, then, that we would expect sanctions like public shaming to be more effective. And this is because, as I show below, the higher transitivity of a closed network helps to facilitate the social conditions that productive public shaming requires.

Shared Norms and Authority to Sanction

As a set of informal rules guiding appropriate modes of behavior, social norms “constitute an important component of stable society’s self-governing mechanism” (Coleman Reference Coleman1990a, 242). Because we live with other people, the consequences of our actions are often felt by others. Norms arise when a group of people recognize that they have a shared interest in managing those consequences; they are a method of social control. But for norms to serve this stabilizing function, everyone involved must, first, share the expectation that those norms exist and are sanctionable (Bicchieri Reference Bicchieri2016). There must also be “consensus that the right to control an action is held by persons other than the actor” (Coleman Reference Coleman1990a, 243). For public shaming to work as a method of social control, it requires recognition—by the target of shaming and those observing—that the shamers have the authority to sanction the actions of the shamed based on a set of shared norms. Only when shamers have the recognized authority to sanction norm violations on behalf of the community can public shaming serve as a mechanism of social control (Adkins Reference Adkins2019).

A closed network structure can help members agree on both what those shared norms are and others’ right to sanction violations of them.Footnote 3 Within closed networks, members are more likely to understand and experience the (often unintended) consequences of their own, and others’, actions; as a result, they are more likely to develop the expectations that norms are required to control those actions. And by facilitating a sense of the need for social norms to control behavior, a closed network also facilitates recognition that those norms must be enforced. Within a closed network, people are more likely to see themselves as members of a community, develop a vested interest in managing it, and exert social control to do so.

Reputational Considerations

In addition to recognizing the shamer’s authority to sanction violations of shared norms, effective public shaming also requires the presence of reputational considerations on the part of the shamed. Since public shaming is a “reputational punishment” (Aitchinson and Meckled-Garcia Reference Aitchinson and Meckled-Garcia2021, 2)—the force of which is found in its ability to diminish one’s standing within a community rather than material penalties—targets of shaming must care about their reputation if the shaming is to have a corrective effect. Indeed, we can imagine a scenario where a norm violator knows about a norm, and perhaps even recognizes others’ right to sanction violations of it, but remains impervious to the threat of punishment because they simply do not care.

While there are individual characteristics that play a role, the reputational considerations at stake in effective sanctioning are also influenced by the wider social networks in which individuals are embedded. “Reputation,” Coleman (Reference Coleman1988, S107) tells us, “cannot arise in an open structure” because it is only in closed networks that interactions are structured in ways that “bring an individual face to face with the same individual over a whole sequence of interactions” (Coleman Reference Coleman, Cook and Levi1990b, 254). A closed network incentivizes reputational considerations by facilitating the repeated interactions upon which reputation depends (Kanagaretnam et al. Reference Kanagaretnam, Mestelman, Nainar and Shehata2010; Molm, Takahashi, and Peterson Reference Molm, Takahashi and Peterson2000). In a closed network—one in which repeated encounters are more likely—it is more important that one maintains a trustworthy reputation. This is, in part, because there are a limited number of “nodes,” which means you are more likely to interact with others. But a closed network also facilitates more effective information spread, so that word of “bad behavior” can move quickly among members of the network—even if they are not engaged directly.

Possibility for Reintegration

While recognition and reputational considerations are necessary for public shaming to effectively sanction social norms, they are not sufficient to ensure that shaming will operate in a productive way—as a form of integrative social control—rather than exhibit pathologies of stigmatization or harassment. For public shaming to effectively sanction behavior, scholars argue, it must occur in a context where there is the possibility of reintegration (Chen Reference Chen2002; Schaible and Hughes Reference Schaible and Hughes2011). There must be opportunities for the shamed to atone for their violation and be accepted back into the community “through words or gestures of forgiveness or ceremonies to decertify the offender as deviant” (Braithwaite Reference Braithwaite1989, 100–1). Absent the possibility for reintegration, shaming becomes a “disintegrative” process in which “no effort is made to reconcile the offender with the community” (Braithwaite Reference Braithwaite1989, 101)—in other words, shaming becomes exile.

In order for reintegration to take place, however, there must be something to reintegrate in to; this is why, Braithwaite (Reference Braithwaite1989) argues, reintegrative shaming must take place within a community with high interdependency. Thus, Massaro (Reference Massaro1991) agrees, shaming sanctions tend to “work best within relatively bounded, close-knit communities, whose members ‘don’t mind their own business’ and who rely on each other” (1916). In this kind of interdependent environment, it is easier for targets of shaming to identify both who and what must be satisfied for reintegration to take place. Absent clear criteria for apology and atonement, the shaming will likely result in stigmatization. This possibility of reintegration is a key component of public shaming’s effectiveness as a mode of productive sanctioning; caring about one’s reputation is futile, after all, if there is no hope of recovering it.

This, too, is influenced by network structure. A closed network—one in which, recall, members are more likely to recognize shared norms—is one in which the shamed is more likely to understand how to reintegrate precisely because of those shared norms. In an open network, these conditions are less well-defined. Because open networks have fewer ties—with fewer repeated encounters and lines of communication—between their members, it is more difficult for targets of shaming to reintegrate; rather than facilitate the kind of community knowledge that makes reintegration possible, open networks instead incentivize members to “squeeze the identities of offenders into crude master categories of deviance” (Braithwaite Reference Braithwaite1989, 97). In an open network structure, because members have relatively little interaction with one another, it is more difficult for targets of shaming to know precisely how to atone and recover their reputation. Instead, the publicly shamed remain stigmatized as deviant, inviting precisely the kind of pathological behavior often associated with OPS.

Designing for Closed Networks

For public shaming to be effective, as we have seen, it must occur within a social context that facilitates recognition of shared norms, reputational considerations, and the possibility for reintegration—the conditions that help make shaming a productive and integrative form of social control, rather than a pathological punishment. Closed networks, as I have shown, contribute to this difference in outcome. And we can understand the dynamics of closed networks—how they facilitate productive public shaming, as well as how they are developed in the first place—by looking at the example of the Quiet Car.

Quiet Cars are demarcated train cars on commuter rail lines with strong norms of silence, intended to provide quiet spaces to work or relax. Though there are often signs demarcating the Quiet Car and outlining its rules, formal enforcement is uneven, at best, since conductors are not always present. Instead, the norm of quietness is (famously) upheld by other passengers, especially frequent riders, who have a vested interest in making the commute a quiet one. By recognizing this shared interest in a strong norm of quietness, the Quiet Car riders also recognize the community’s shared authority to sanction—by publicly “shushing,” if nothing else—those who violate this norm (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2014). And, importantly, this sanctioning is aimed largely at the act rather than the rider; once the shamed stops being loud—often with a quick apology—they are welcomed back into the Quiet Car community.

Yet not all train riders will feel the power of this public “shushing” sanction. It is the car’s regular riders who are more likely to want to maintain their reputation as norm-followers because they repeatedly encounter one another by virtue of their shared commute. “Tourists,” by contrast—or infrequent Quiet Car passengers—may not develop the same reputational considerations because this threat of repeated interaction is minimal. For tourists, the network of the Quiet Car is more open—they have no connections to other riders beyond their single ride. While they may be aware of norms of silence (Quiet Cars are often well-signed!) and acknowledge other riders’ right to “shush,” this public sanction may not have the intended effect; because the reputational considerations are lacking, tourists are just not as incentivized to care.

Public shaming is more likely to be successful within the confines of the Quiet Car because of the closed network that car engenders. And there are certain environmental features of the Quiet Car which help to facilitate this closed network. In contrast to the rest of the train, the Quiet Car is set apart as a clearly defined space; most who enter the Quiet Car do so precisely because they share the norm of quietness that visibly demarcates it. Moreover, by virtue of this buy-in—and the regularity of commuting—riders in the Quiet Car are more likely to encounter one another repeatedly; because there is (usually) only one Quiet Car, that space is the only option available for those who value quietness. By providing a well-defined space in which shared norms are clearly expressed and riders can be socialized into them, then, the Quiet Car’s environmental characteristics help to generate a more closed network among its riders.

In digital environments, like those of social media, these environmental characteristics can be harder to replicate. Indeed, as Coleman (Reference Coleman1993) warned, “[t]he closure of social networks has been destroyed by the technological changes that have expanded social circles and erased the geographic constraint on social relations” (9). But this loss, Coleman continues, “is correctable in society through the explicit design of institutions” (Coleman Reference Coleman1993, 10). In addressing the problems of OPS, then, the challenge we face is partly one of thoughtful and intentional design choices: to facilitate productive OPS, we must design systems with “sufficient closure and continuity” (Coleman Reference Coleman1993, 12). Analyzing the dynamics of OPS on different social media platforms can help us understand how to do just that.

“MOSTLY AN EXAMPLE OF TWITTER RUN AMOK” Footnote 4

Echoing Coleman’s warnings, many scholars point to the ways that social media’s affordances—including increased speed, scale, and surveillance capacity, as well as individual “disinhibition” facilitated by anonymity (Ge Reference Ge2020)—are altering the who and the how of public shaming. OPS often follows a familiar pattern: someone’s “bad” behavior is uploaded to social media—usually Twitter—where it begins to circulate. Aided by high-follower accounts who retweet it and hashtags that begin to “trend,” the person’s behavior becomes the subject of intense scrutiny. As part of this process, many times users will “dox” the target of shaming, calling for “real world” punishments by revealing personal information—like the target’s name, location, and employer—often drawn from other public social media accounts. The result, as many have argued, is a full-scale mobbing that destroys lives and often leaves the targets depressed, resentful, and bewildered (Ronson Reference Ronson2015).

And, critics argue, this is to be expected. With social media, more “individuals [are] now armed with an unparalleled ability to watch, evaluate, and reprimand other people on the internet for supposed deviances from social norms” (Muir, Roberts, and Sheridan Reference Muir, Roberts and Sheridan2021, 1). And our actions can linger, as videos circulate and recirculate. By transforming the scale of public shaming (Frye Reference Frye2022), scholars agree that digital technologies—and social media in particular—turned a perhaps-once-productive practice of social sanction into a kind of pathological “norm enforcement that is indeterminate, uncalibrated, and often tips into behavior punishable in its own right” (Klonick Reference Klonick2019, 1032).

This concern is not unfounded. Recent work confirms that OPS events, though most often characterized by jokes and judgments, also often include personal abuse, insults, and slurs (Basak et al. Reference Basak, Sural, Ganguly and Ghosh2019). And there is clear evidence that women and people of color are more likely to be targets of online harassment and threats (Sobieraj Reference Sobieraj2020). Yet making proclamations about OPS based solely on this dimension risks overgeneralizing. For one, it overlooks the myriad ways that many social media users deploy public shaming as an ordered, reintegrative, and ultimately productive form of social sanction (Clark Reference Clark2020). Indeed, early platforms like Cyberworlds and eBay operated with robust and effective mechanisms of public shaming as a tool of social control (Williams Reference Williams2006). And there are contemporary large-scale online platforms, like Threadless (with around three million monthly active users), that utilize sanctioning practices like public shaming as a productive form of social accountability—without a negative shift into harassment and threats (Bauer, Franke, and Tuertscher Reference Bauer, Franke and Tuertscher2016).Footnote 5

Attending to network structure’s role in facilitating the conditions required for productive public shaming can help account for these differences between cases of OPS. We know that certain social contexts make effective public shaming more likely. And we know that closed network structures—like the kind often facilitated by well-defined offline spaces like Quiet Cars—help to create these contexts. But the same design characteristics that mark these offline spaces can also be present in online environments as well.

In this section, I compare the design of two major social media platforms to show how they facilitate different network structures among users, with important consequences for how OPS plays out.Footnote 6 Twitter, for example, is characterized by a more open network among users that incentivizes pathological OPS on the platform. By contrast, Wikipedia facilitates a community characterized by a more closed network that makes OPS a viable mechanism of productive social norm enforcement. By examining the design elements that influence these platforms’ network structures, we can better identify how, why, and under what conditions OPS may work effectively as a mode of social sanctioning and when it is likely to devolve instead into harassment, bullying, and threats.

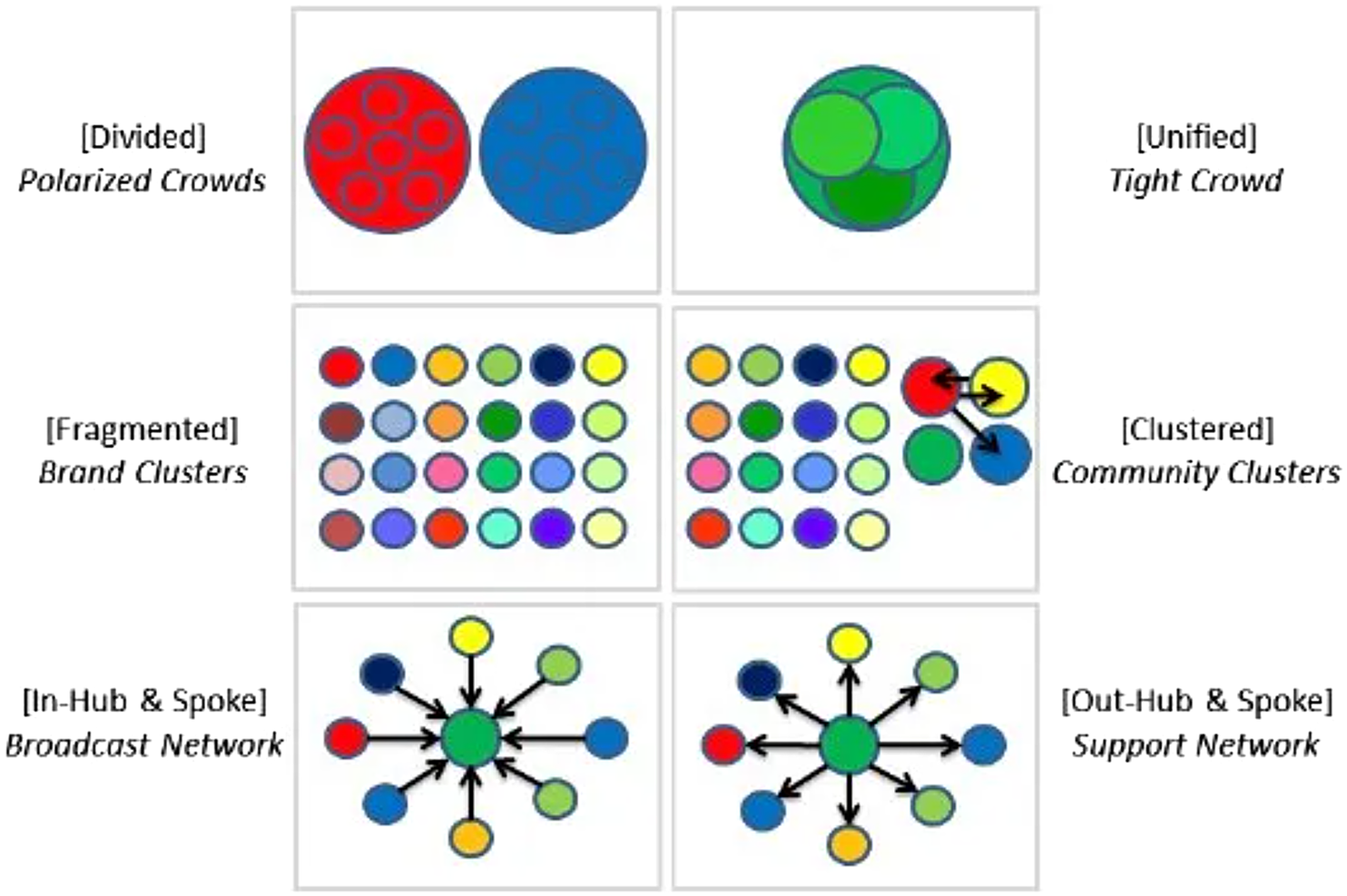

Twitter is designed to prioritize individual connections. Unlike Facebook, on which “Friendships” must be reciprocated, Twitter’s user relationships are often asymmetrical. Users can opt to “follow” those users whose tweets they wish to see regularly; there is no obligation, however, that anyone will “follow back.” And they largely do not (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Rainie, Shneiderman and Himelboim2014). Instead, Twitter tends to facilitate a more hierarchical network structure, characterized by high-follower “hubs” with many spokes but few connections between them (Himelboim et al. Reference Himelboim, Smith, Rainie and Espina2017; see Figure 2).Footnote 7 And Twitter has, over time, made changes to its user experience, like introducing a sorting algorithm, which likely work to further cluster users around high-profile accounts, exacerbating this asymmetrical effect (Oremus Reference Oremus2017).Footnote 8 By encouraging “the formation and maintenance of looser, distal ties, or a mix of close and loose ties wherein reciprocity is more arbitrary” (Shane-Simpson et al. Reference Shane-Simpson, Manago, Gaggi and Gillespie-Lynch2018, 285), Twitter connects users in an open network structure. And this open network structure is why, I argue, OPS on Twitter is more likely to exhibit the pathologies scholars describe.Footnote 9

Figure 2. The Six Structures of Twitter Conversation Networks

Note: Of the six most common conversation networks on Twitter, only one (“Tight Crowd”) is characterized by the high interconnectedness of a closed network. Tight crowds are often associated with conference hashtags and other offline communities. By contrast, the other common conversation patterns are more characteristic of open networks, with fewer overlapping connections between users. Image reproduced with permission from Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Rainie, Shneiderman and Himelboim2014).

Because the network is largely open, Twitter users are generally unable to identify shared norms; there is also no recognition of a collective authority to sanction those norms.Footnote 10 Instead of a community, Twitter is better understood as an aggregation of individuals who may be talking about the same thing.Footnote 11 For the same reasons, targets of Twitter shamings are unlikely to develop the reputational considerations required for productive shaming. With little sense they will encounter one another again—or even that they share network connections—there are few reasons for Twitter users, as such, to care about others’ opinions of them. Finally, even if targets of Twitter shamings do want to atone for their misbehavior, there is no clear mechanism for this kind of reintegration. Targets of Twitter shamings cannot be reintegrated into a community if that community does not exist.

Consider the case of Amy Cooper—a typical example of how OPS unfolds on Twitter. In May 2020, Cooper (the “Central Park Karen”) was publicly shamed on Twitter for calling the police on Christian Cooper, a Black birdwatcher who confronted her about her off-leash dog in Central Park’s Bramble. But rather than a coordinated, collective rebuke of a clearly defined norm violation against a recognizable community, Cooper’s shaming overwhelmingly consisted of a series of individual responses, each with their own focus and tenor; there was disagreement among Twitter users over precisely what norms Cooper violated or what, if anything, she could do to atone.

Moreover, Twitter’s open network structure meant that Cooper had fewer reputational considerations that would lead her to take the reputational threat of public shaming on Twitter to heart. The consequences she did face—like a loss of employment—were not primarily the reputational sanctions of public shaming, but rather the more severe, and tangible, punishments of material losses. Moreover, these punishments lacked any kind of reintegrative function. And this, again, is to be expected. Those entities that did the punishing, such as her employer, were not necessarily part of the same network—or at least were not recognized as such—as those shaming Cooper on Twitter. Just as there was disagreement over what norms Cooper violated, it was also not clear what community she needed to reintegrate into or how to go about doing so. We should therefore not be surprised that the shaming was not only ineffective as a form of sanction—in May 2021, Cooper sued her employer, invoking the same racist dog-whistling she was shamed for a year priorFootnote 12—but that it also developed the pathologies of disproportionate harassment that scholars of OPS warn of.

While scale certainly contributes to the pathologies of OPS on Twitter—the aggregation of thousands of retweets, likes, and comments can itself be overwhelming (Bloom and Jordan Reference Bloom and Jordan2018)—it cannot fully account for what went wrong in Cooper’s case and others like it. The problem is not simply that many people are involved in sanctioning; it is also that the sanctioning lacks direction. Twitter’s open network structure facilitates conditions under which targets of shaming face discordant, vague criticisms from random strangers, rather than a coordinated, specific sanctioning by authoritative members of a recognized community. But the same is not necessarily true of all social media platforms. Indeed, as I show below, there are instances of OPS on other platforms that, unlike Twitter shamings, work effectively as a form of social sanction. These other platforms—notably, Wikipedia and Reddit—also involve a large scale. Yet they have effectively wielded OPS as a tool of social control to build longstanding communities online. Attending to the role of network structure, I argue, can help explain why.

Wikipedia

First organized in 2001, Wikipedia is (in)famous as the “free encyclopedia” that anyone can edit. Despite this lack of gatekeeping, Wikipedia has become an invaluable source of human knowledge. As of 2022, the site boasts more than 58 million articles in over 300 languages; the English version alone has over 6.4 million articles (Wikipedia:About 2022). While the platform has faced serious criticism regarding its lack of diversity—of both editors and articles (Ford and Wajcman Reference Ford and Wajcman2017)—it nevertheless hosts over 130,000 active contributors (self-titled “Wikipedians” or “editors”) who not only produce a high-quality public good (The Economist 2021) but also serve as “a model for many forms of social endeavor online” (Cooke Reference Cooke2020).

As perhaps the most ambitious and successful collaborative project on the internet, scholars have spent considerable time and effort to understand how precisely Wikipedians are able to maintain such high standards of quality in an environment with little formal authority and the possibility that anyone—even trolls—can contribute.Footnote 13 Scholars have shown, for example, the importance of diverse contributors and role diversification (Welser et al. Reference Welser, Cosley, Kossinets, Lin, Dokshin, Gay and Smith2011) and have examined the patterns of communication and collaboration between editors (Rychwalska et al. Reference Rychwalska, Talaga, Ziembowicz and Jemielniak2021). But, as is the case for many online communities, the main driver of order on Wikipedia is the existence, and enforcement, of social norms (Goldspink Reference Goldspink2010, 654).

While Wikipedia has gradually developed more “bureaucratic rules” and “standardized and transparent procedures” to govern disputes (Rijshouwer, Uitermark, and Koster Reference Rijshouwer, Uitermark and Koster2021, 14), the majority of sanctioning on the platform remains informal—editors sanction other editors, thereby socializing them into the community’s norms (Morgan and Filippova Reference Morgan and Filippova2018). In perhaps the most visible rebuke of one’s editing behavior, an editor’s changes to an article might be “reverted”—meaning they are removed from the article entirely, indicating they do not meet the community’s norms of quality. These public, yet informal, social sanctioning mechanisms work precisely because Wikipedia provides the social conditions required for sanctions like public shaming to be an effective form of social control.

For one, Wikipedia hosts a well-defined community, with a set of clear norms—like the “neutral point of view”—widely distributed among community members; editors likewise recognize the community’s authority to sanction editors who violate those norms (Piskorski and Gorbatâi Reference Piskorski and Gorbatâi2017). And these sanctioning practices are effective, in part, because editors care about their reputations in the community. As Wikipedia itself makes clear, the “community is founded on individual reputation and trust” (Wikipedia:Expectations and Norms of the Wikipedia Community 2022). The importance of one’s reputation is therefore paramount: “Past behavior, recorded in each editor’s contribution history,” continues the Expectations page, “may be a factor in community discussions related to sought positions of trust or potential sanctions.” Editors therefore have good reason to maintain their standing in the community; their ongoing ability to contribute to the project depends on it.

But sanctioning on Wikipedia need not destroy one’s reputation. Though sanctions like reverts are public, they are also understood as a rebuke of the editor’s actions, not the offending editor as such. Editors can explain their edits on the article “Talk” pages, where they become the subject of discussion or justification with other community members. Simply having one’s edits reverted is thus not cause for stigmatization—though such ostracism may occur if an editor fails to acknowledge the public sanction and atone for their bad behavior and instead engages in a “revert war” whereby they continue readding the deleted material.

Wikipedia exhibits these social conditions that contribute to productive shaming, in part, because of the community’s social network structure. While Twitter facilitates a more open network among its users, Wikipedia cultivates a more closed network. And this is due, at least in part, to the way the platform is designed. Unlike on Twitter, Wikipedia users engage with one another in discrete spaces— for example, article Talk pages, the Teahouse, and WikiProjects.Footnote 14 Moreover, individual editors often work on a subset of articles, where they encounter one another repeatedly. The individual article pages work like the space of the Quiet Car; within them, editors tend to form closer, reciprocal relationships with one another (Lerner and Lomi Reference Lerner and Lomi2020) and these Wikipedians, with more reciprocal ties, are more likely to enforce norms and less likely to violate them (Piskorski and Gorbatâi Reference Piskorski and Gorbatâi2017).

Because Wikipedia is organized around durable, bounded spaces like Talk pages, editors can more easily identify agreed-upon social norms and recognize others’ authority to sanction violations of them. The repeated encounters such spaces engender—and the community they generate—make editors’ reputational considerations salient. And these clear norms and community attachments also give norm violators a sense of how to properly atone once sanctioned, directing them how to reintegrate and regain standing within that community. The result is a large-scale social media platform on which public sanctioning practices serve as a productive mechanism of social control.

COMPLICATING NETWORK STRUCTURE: THE CASE OF REDDIT

As a clearly defined collaborative endeavor where editors are coproducers of a tangible product, Wikipedia is unusual among online communities. But despite its idiosyncrasies, Wikipedia is not alone in its successful use of OPS. As we saw in the introduction, Reddit also hosted a productive shaming of european_douchebag—at least initially. After posting a photo of a Sikh woman to r/funny, european_douchebag was shamed by his fellow Redditors. He soon apologized and the matter was seemingly resolved until he explained, one day later, that he was deleting his account due to receiving relentless harassment. Returning to this example, using the lens of network structure developed above, not only shows how Reddit’s design can help facilitate productive OPS, but also reveals additional nuances in cases of OPS overlooked by a singular emphasis on scale.

Revisiting European_douchebag

Compare the cases of Amy Cooper and european_douchebag: both involved individual norm violations that resulted in shaming on two large-scale social media platforms and ultimately made national news. But the social contexts of the two shamings varied considerably. Unlike Amy Cooper, who was shamed in Twitter’s open network, european_douchebag’s shaming occurred on Reddit. Reddit is a popular social media platform that hosts over 330 million monthly active users in around 140,000 subreddits, which are organized around a variety of user-driven interests and often support all kinds of collective action (Flores-Saviaga, Keegan, and Savage Reference Flores-Saviaga, Keegan and Savage2018; Matias Reference Matias2016; Mills and Fish Reference Mills and Fish2015; Tiffany Reference Tiffany2020).

Reddit’s subreddit structure facilitates more closed networks among users (Choi et al. Reference Choi, Han, Chung, Ahn, Chun and Kwon2015). Like Wikipedia’s Talk pages, Reddit’s subreddits are discrete spaces that house clearly defined communities. Upon entering a subreddit, the group’s shared norms are clear; engagements with other Redditors happen within this collective context. As a result, the subreddit design encourages users to recognize their membership in a community with shared norms and the authority to sanction them; moreover, they facilitate the repeated interactions that make reputation meaningful. This social context means that Redditors can, and do, use public shaming productively as a tool of social control, even in large-scale digital environments with millions of users. And we can see the effects of Reddit’s closed network context in european_douchebag’s shaming.

In r/funny, european_douchebag was shamed by a cohesive community with clearly shared norms and of which he was a member. And this shaped his response. Throughout his comments, european_douchebag not only identifies how he violated the specific shared norms of r/funny, but also recognizes his fellow Redditors’ authority to sanction his actions. As part of his apology, he acknowledges that

r/Funny wasn’t the proper place to post this. Maybe r/racism or r/douchebagsofreddit or r/intolerance would have been more appropriate…I’m sorry for being the part of reddit that is intolerant and douchebaggy. This isn’t 4chan, or 9gag, or some other stupid website where people post things like I did. It’s fucking reddit… So reddit I’m sorry for being an asshole and for giving you negative publicity.

(european_douchebag 2012a)In this apology, european_douchebag is drawing on the specific expectations of Reddit—and r/funny in particular—in framing his response. Contrast this with Cooper’s apology to Christian Cooper and “everyone who’s seen that video, everyone that’s been offended… everyone who thinks of me in a lower light and I understand why they do” (Price, Beckford, and Intarasuwan Reference Price, Beckford and Intarasuwan2020). Where european_douchebag explicitly identifies both the norms he violated (of anti-racism, tolerance, and anti-“douchebaggery”) and the community he is apologizing too (Reddit and r/funny), Cooper’s apology lacks this specificity. Further, european_douchebag concludes his apology by reiterating his commitment to Reddit’s norms, noting that “Just because you’re anonymous doesn’t mean you can be an asshole” (european_douchebag 2012a). Later, he downplays the significance of the apology, claiming “I don’t think I did anything special, it was just an apology,” indicating that he does not see this atoning as taking extraordinary measure, but rather simply meeting the expectations of his community.

If his apology signals shared expectations around r/funny’s norms, european_douchebag’s posts also reveal the reputational considerations that make OPS an effective form of social sanctioning. In his apology, he notes that he made the original post “for stupid internet points” (european_douchebag 2012a).Footnote 15 And, as the shaming began, he responded at one point by sharing his hopes that “you guys [the other Redditors] won’t remember me as ‘that douchebag that posted the picture of the Sikh girl!’” In both cases, we see evidence that european_douchebag cared what his fellow Redditors thought of him and attempted to behave in a manner that would be viewed favorably—though he obviously misjudged this initially.

Finally, other Redditors’ comments signal the possibility for european_douchebag’s reintegration, post-shaming. While there are plenty who remained skeptical of his changed heart, the comments on european_douchebag’s apology post largely commended him for apologizing. Notably, even the skeptics acknowledged the power of OPS in changing Redditors’ behavior; their skepticism was not about whether european_douchebag atoned for his violation, but rather his motive for doing so. One asked, rhetorically, “You think he would have even considered apologizing if this had not blown up? Ridiculous.” Another simply acknowledged that “Reddit is full of assholes until they get called out.” Here, we see that even those who viewed european_douchebag’s response less charitably nevertheless recognized the power of public shaming in bringing about his public apology.Footnote 16 In this example, then, we see european_douchebag’s shaming play out in a specific context that contributed to its more positive outcome—the network structure of r/funny was more closed than that of Twitter, making it easier for european_douchebag to contextualize his shaming and respond productively.

But, of course, though european_douchebag’s shaming might have begun as an example of productive OPS—in that he acknowledged his norm violation, apologized, and was welcomed back into the community after atoning—it did not end that way. One day after apologizing and receiving a positive response from r/funny, european_douchebag deleted his account citing relentless harassment by Redditors and media alike. But while this deletion may seem to confirm critics’ claims regarding the pathologies of large-scale OPS, a closer look at the circumstances surrounding european_douchebag’s shaming uncovers more complex dynamics.

Beyond Open and Closed

The example of european_douchebag suggests how more closed networks—like the r/funny subreddit—can help mitigate some of the pathologies associated with large-scale OPS. But it also highlights the ways that digital technologies often facilitate network structures that transcend a simple distinction between open and closed in ways that further complicate the dynamics of OPS. As we saw, while european_douchebag eventually deleted his account, citing common OPS pathologies, prior to that he had a seemingly productive shaming experience—one that resulted in his own change of heart as well as reinforced the norms of r/funny. Examining this case through the lens of network structure can help us to untangle some of this seeming contradiction by revealing nuances to OPS that cannot be captured when focusing on scale alone.

For one, the case of european_douchebag shows how easily OPS can move between networks, with different effects. Crucially, while european_douchebag’s shaming initially occurred within the relatively closed network of r/funny, it did not remain contained to this original context. Rather, the shaming “escaped” when the incident was publicized by national news media like HuffPo and CNN, as well as covered on other subreddits like r/goldredditsays, r/feminism, and r/defaultgems (each with thousands of members). The result was that european_douchebag was soon subject to shaming in many different contexts: not only in the more closed network of r/funny, but also in the more open networks of Reddit and the media. And, as might be expected, once the shaming escaped its original closed network of r/funny, it also became less productive and more pathological.Footnote 17

But in demonstrating the ease with which OPS can “escape” specific networks online, the european_douchebag example also shows how the structures of interaction on social media platforms resist easy classification into open versus closed networks. As I have argued, r/funny is a more closed network from the perspective of its members, especially compared to Twitter. But it is, importantly, not hermetically sealed.Footnote 18 As a page that everyone can visit, content on r/funny is accessible to “lurkers.” Anyone can read the exchanges in r/funny without participating in them or even being visible to the actual members of that subreddit. This can, in part, explain the trajectory of european_douchebag’s shaming; it was nonmember observers—like journalists—who moved the shaming from a single closed network into multiple more open ones as they publicized the story more widely. Rather than retain the specificity of the r/funny context, this move meant that european_douchebag’s behavior was soon subject to scrutiny from vaguely defined “publics” he did not have the same relationship with—a situation more like Cooper’s on Twitter. And this was made possible, in part, because the initial shaming that took place within r/funny’s closed network was visible to people outside of it.

Network structure can thus help explain the apparent contradiction in european_douchebag’s OPS experience; his shaming was both productive and pathological because it occurred in different kinds of networks almost simultaneously. On the one hand, european_douchebag could easily contextualize his initial shaming and respond to the rebuke from r/funny members for what it was—a collective sanctioning for violating a shared community norm. On the other hand, european_douchebag’s experience of OPS also devolved when nonmember observers moved it from the more closed context of r/funny into the more open network of mass media and Reddit more generally.Footnote 19 The result is that european_douchebag was subject to OPS pathologies like harassment and harm just as others, like Cooper, were.

But, crucially—unlike Cooper and others—european_douchebag also continued to describe his experience of public shaming as positive and transformative, even after experiencing its pathologies. Recall that, after deciding to delete his account, european_douchebag felt obligated to explain that decision to the r/funny community; even then, he insisted that the experience was positive and that “My apology to [the woman photographed] was sincere. People can say what they want but in my heart and hopefully hers, it was sincere.” By attending to the network structures involved, we can better understand why european_douchebag had such a different reaction to his shaming, even though he cited an OPS experience characterized by certain pathologies—like receiving death threats and relentless reminders of his mistake—similar to Cooper’s. The original context of r/funny’s more closed network helped ensure that european_douchebag’s shaming remained, at least in part, productive.

Naming and Shaming

Of course, european_douchebag—unlike Cooper—was also able to mitigate many of the harms associated with pathological OPS simply by deleting his Reddit account. Some—including european_douchebag himselfFootnote 20—may thus attribute these differences in outcome to the use of Amy Cooper’s “real” name versus european_douchebag’s Reddit-specific pseudonym. Because european_douchebag could eventually discard his online identity, so this argument goes, he may not have experienced the pathologies of OPS as powerfully as Cooper did. There may be some truth to this claim—but it, too, is influenced by network structure.

The reputational costs of being shamed with one’s legal identity—the costs european_douchebag was able to avoid by deleting his account—are, scholars have argued, only significant insofar as they reflect our embeddedness within networks of people whose opinions matter to us (boyd Reference boyd2012; Forestal Reference Forestal2017). Because european_douchebag used a unique pseudonym, his reputational considerations were contained within the relatively closed network of the Reddit platform; only within that specific community did his name have meaning. This is not to say european_douchebag’s use of a pseudonym negated the reputational considerations at stake in public shaming; as we saw, there is strong evidence that european_douchebag cared deeply about how other Redditors perceived him. But the use of a pseudonym did mean that european_douchebag was able to manage his networks and keep them separate. His behavior—and the resulting reputation—on Reddit could be contained to that context without necessarily impacting other spheres, like european_douchebag’s home or workplace, where his legal identity was used instead. Moreover, when the shaming did “escape”—as it did when the news of his shaming spread—he was able to manage the consequences by deleting his account.

Cooper, by contrast, was shamed using her legal identity. Because one’s legal name usually has meaning within many different networks—among them, family, friends, and workplaces—the use of Cooper’s legal name made it more likely that her reputational considerations would expand beyond a single network without recourse.Footnote 21 In effect, shaming Cooper with her legal identity led to a type of unintentional context collapse that Davis and Jurgenson (Reference Davis and Jurgenson2014) call “context collision.” Ultimately, being shamed with her legal identity meant Cooper’s shaming could more easily “escape” beyond Twitter into her personal and professional lives. The use of Cooper’s legal name, then, rather than meaningful in itself, was significant because it left her no way to contain her shaming to the relevant community—a community that did not exist in the first place because she was originally shamed in Twitter’s open network.Footnote 22 While naming conventions certainly contributed to the differences between Amy Cooper and europrean_douchebag’s shamings, then, they cannot fully account for these differences. Instead, by attending to the ways that names—like scale—are mediated by network structure, we can better understand the complexities of OPS as they unfold.

SOCIAL MEDIA AND SOCIAL CONTROL

OPS is a concern for those invested in ensuring the internet is safe and welcoming for all. As a result, scholars have suggested strategies for mitigating the pathologies of OPS—solutions that largely center on adopting new social norms, whether around the appropriate scale of public shaming (Frye Reference Frye2022) or “about the use of the Internet” more generally (Billingham and Parr Reference Billingham and Parr2020a, 1011). As I argue, however, the kind of social norm creation and enforcement these scholars appeal to is more effective within a specific network structure. In more closed networks, like those of Reddit and Wikipedia, it is easier for members to agree upon shared norms and accept sanctioning to enforce them. In more open networks, like that of Twitter, it is less likely members will share norms or recognize others’ authority to sanction them. And yet these distinctions are not binary, as online behavior can easily spread from one network into others, complicating this open/closed dichotomy. As we work to reshape online behavior around the use of OPS, then, our goal should be to develop norms and enforcement practices that are responsive to these structural distinctions. To that end, widening our focus from scale to network structure not only helps to explain some seeming contradictions in different cases of OPS, but also opens several new possibilities for future research to help mitigate its pathologies.

One such area of investigation is that of enforcement practices. We know that platforms with more closed networks, like Reddit, have successfully established norms—for example, against doxxing and harassment (Fiesler et al. Reference Fiesler, Jiang, McCann, Frye and Brubaker2018)—that scholars argue will help protect against OPS harms (Billingham and Parr Reference Billingham and Parr2020a). These norms are most often enforced actively, by user-moderators empowered to punish by banning or blocking members and removing content. But we have also seen successful instances of passive enforcement, in which shared norms are made explicit through regular, visible reminders that nevertheless increase norm compliance among users (Matias Reference Matias2019). What remains to be seen, however, is whether these same kinds of enforcement practices are as effective in more open networks. Indeed, the kind of platform-sanctioned, community-led active moderation we see on Reddit and Wikipedia may not be feasible on Twitter, where the community is less well-defined (if not nonexistent); instead, “top-down” corporate moderation may be the most effective, though imperfect, means of active enforcement. At the same time, there is some evidence that simply “nudging” Twitter users to abide by norms against, for example, offensive speech can be effective at shifting behavior (Katsaros, Yang, and Fratamico Reference Katsaros, Yang and Fratamico2022). It is possible, then, that this more passive intervention—one that reminds users of shared norms and helps them conceptualize their role in a larger community—might work to help mitigate some pathologies of OPS, even in open networks. But more research is required to determine precisely which enforcement practices are best suited to what network structures.

In studying norm enforcement practices, scholars should also attend to the fact that network structure can be characterized along several dimensions, many of which are likely to affect OPS outcomes. In this article, I have argued that network transitivity, or the degree of closure, is one aspect of network structure to which we should attend. But it is not the only one. Future research might also focus on the network’s degree of homophily, or similarity between actors; it is plausible that open, yet homophilic networks are able to overcome incentives to pathologize OPS. Or scholars might investigate the multiplexity of networks, as networks with higher degrees of multiplexity—or overlapping network contexts (e.g., people connected by both work and family)—might also constrain behaviors in ways that mitigate the pathologies of OPS, even if the networks themselves are more open. Finally, we might study how OPS changes given actors’ positions within the network (e.g., their centrality). More “central” nodes in a network—those with more influence—may be subject to greater scrutiny, due to their higher visibility; on the other hand, their role in facilitating the network may give them a “pass” on “bad” behavior—only more research can tell.

Finally, in calling for more scholarly attention to the role of network structure, I am not making the case that structure alone determines OPS outcomes. With this in mind, scholars interested in OPS should also consider how the pathologizing incentives of open networks might be mitigated by other factors—not just enforcement practices, but also, as Jacquet (Reference Jacquet2015) suggests, considerations such as the type of norm violation and the magnitude of shaming’s benefits. There is good reason to think, as I have argued, that these variables intersect with network structure in ways that are meaningful for shaping OPS outcomes. But more research is required if we are to understand precisely how, so we may best ensure that OPS works productively as a form of democratic social control.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Yuna Blajer de la Garza, Danielle Hanley, Eric Hansen, Sarah Maxey, Menaka Philips, Kara Ross Camarena, and Abe Singer for their helpful feedback on this project in its various stages. Earlier drafts of the article were presented at the 2022 WPSA, APSA, APT, and PPE conferences; thanks to Colin Koopman, Spencer McKay, and Michelle Chun for their thoughtful comments, and to the other panelists and participants for insightful discussion.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The author affirms this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.