Introduction

In most high-income countries, alcohol is the most prevalent psychoactive substance used. In many European countries, the use of alcohol and attributable disease burden remains high despite slight decreases in the past decades [Reference Pruckner, Hinterbuchinger, Fellinger, Konig, Waldhoer and Lesch1]. To alleviate the considerable alcohol-attributable disease burden in high-income countries, the World Health Organization recommends strict control policies (e.g., raising taxes or restricting availability) and access to screening, brief interventions, and treatment [Reference Ferreira-Borges, Neufeld, Probst, Burton and Carlin2]. A range of evidence-based and cost-effective psychosocial and pharmacological interventions are available, from brief interventions in primary health care (PHC) for hazardous drinking to specific psychological and pharmacological treatments for long-term and severe alcohol use disorder (AUD) in specialised care [Reference Carvalho, Heilig, Perez, Probst and Rehm3, Reference MacKillop, Agabio, Feldstein Ewing, Heilig, Kelly and Leggio4]. PHC is the entry point into the healthcare system for most people with AUD, where many clinical interventions are delivered [Reference Rehm, Anderson, Manthey, Shield, Struzzo and Wojnar5, Reference Anderson, O’Donnell and Kaner6]. In PHC settings, brief interventions may be offered for those drinking hazardously [Reference Carvalho, Heilig, Perez, Probst and Rehm3] and pharmacological treatments, including detoxification, are targeting those with more severe forms of AUD [Reference Jonas, Amick, Feltner, Bobashev, Thomas and Wines7]. In most jurisdictions, people with AUD are typically referred from PHC to the specialist treatment system [Reference Carvalho, Heilig, Perez, Probst and Rehm3]. In the specialist treatment system, patients with AUD are treated to maintain low alcohol consumption or abstinence after detoxification, initiate lifestyle changes, and prevent relapse [Reference Rehm, Allamani, Aubin, Della Vedova, Elekes and Frick8]. To facilitate and standardise AUD treatment, guidelines with or without pharmacological support are available (e.g., Germany: [Reference Kiefer, Batra, Petersen, Ardern, Tananska and Bischof9]; UK: [10]; global: [Reference Soyka, Kranzler, Hesselbrock, Kasper, Mutschler and Möller11]).

On average, less than one in five people with AUD have utilised alcohol-related treatment [Reference Mekonen, Chan, Connor, Hall, Hides and Leung12]. Treatment demand estimates are typically based on surveys like the World Mental Health Surveys Initiative [Reference Alonso, Angermeyer, Bernert, Bruffaerts, Brugha and Bryson13] where people with AUD report any help-seeking behaviour. This approach identifies individual risk factors linked to treatment demand, for example, higher alcohol intake and high comorbidity [Reference Rehm, Allamani, Elekes, Jakubczyk, Manthey and Probst14]. However, it lacks accurate information on the type and sequence of interventions, for example, actual treatment dates for specific interventions or prescribed medications. Such detailed information is crucial for maximising treatment access and effectiveness as highlighted in a recent study: In people discharged from hospital after an alcohol-related inpatient stay, the administration of medications for AUD was associated with reduced mortality and hospitalisations [Reference Bernstein, Baggett, Trivedi, Herzig and Anderson15].

Acknowledging the constraints of survey data to improve treatment access and effectiveness, it is essential to exploit information from electronic health records. To date, this source of information has been insufficiently analysed to uncover treatment pathways in the context of AUD. Demonstrating the potential of this approach, a recent study from Germany showed that the majority of patients who had undergone inpatient treatment, with or without detoxification, were found to have not utilised post-acute treatment – despite being recommended by official guidelines [Reference Mockl, Manthey, Murawski, Lindemann, Schulte and Reimer16].

In the present study, we seek to comprehensively describe treatment pathways for people with a first AUD diagnosis based on electronic health records from Hamburg, Germany. Specifically, we aim to characterise the population utilising alcohol-related interventions and compare them to people with AUD not utilising alcohol-related interventions to identify barriers to and gaps in treatment access and delivery.

Methods

Data sources and linkage

We obtained regional healthcare data from three different data sources for the years 2016–2021 for people residing in the German city of Hamburg: (a) two statutory health insurance providers (SHIs; AOK Rheinland/Hamburg – Die Gesundheitskasse; DAK – Gesundheit), (b) two German pension funds (PF; Deutsche Rentenversicherung Nord; Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund), and (c) municipality-funded outpatient addiction care services (OACS; from Basisdatendokumentation im Suchtbereich [BADO e.V.]). The data from both SHIs cover about 25% of the adult population in Hamburg and include addiction-specific, as well as other medical outpatient (especially PHC) and inpatient services (hospital stays with overnight stays), outpatient surgeries (hospital stays without overnight stays), and outpatient prescriptions. Data from the PF cover outpatient or inpatient addiction medicine rehabilitation, whereas the OACS data provide information on the utilisation of addiction support services, which mainly cover addiction counselling.

As there is no common identifier in the different datasets, the data holders used a project-specific tool to create cryptographically encrypted identifiers based on personally identifiable variables (first name, last name, birth year, sex). The encrypts were used to identify persons in the different datasets and to link the respective data in one dataset that did contain pseudonymized identifiers only (for a more detailed data linkage description, see [Reference Manthey, Becher, Gallinat, Kraus, Martens and Möckl17]). The data linkage using personal identifying information was approved by the Federal Office for Social Security. This approval exempted us from seeking formal ethics approval as we had no access to personal identifying information at any time but only handled and analysed pseudonymised electronic health records.

Study population

We included SHI-insured patients meeting the following criteria in the analytical sample:

-

1) At least 3 years of complete insurance data

-

2) At least one AUD diagnosis (ICD-10: F10.1-F10.9)

-

3) 12 months before AUD diagnosis (look-behind window): No other AUD diagnosis and no diagnosis indicative of chronic harm from alcohol use (ICD-10: E24.4; G31.2; G62.1; G72.1; I42.6; K29.2; K70; K70.x; K85.2; K86.0; O35.4)

-

4) 24 months of available follow-up period after the AUD diagnosis

For each person, we identified the index date, that is, the first AUD diagnosis that was preceded by no other diagnosis indicative of chronic alcohol use (for more information on the study population definition, see Supplementary Material), followed by a period of 24 months. The choice of 24 months was considered a trade-off between maximising the follow-up and minimising the exclusion of patients due to lack of data. It is important to note that SHI data for more than 6 years are not retrospectively available due to data protection laws requiring any data to be deleted after 6 years.

Alcohol-related treatment

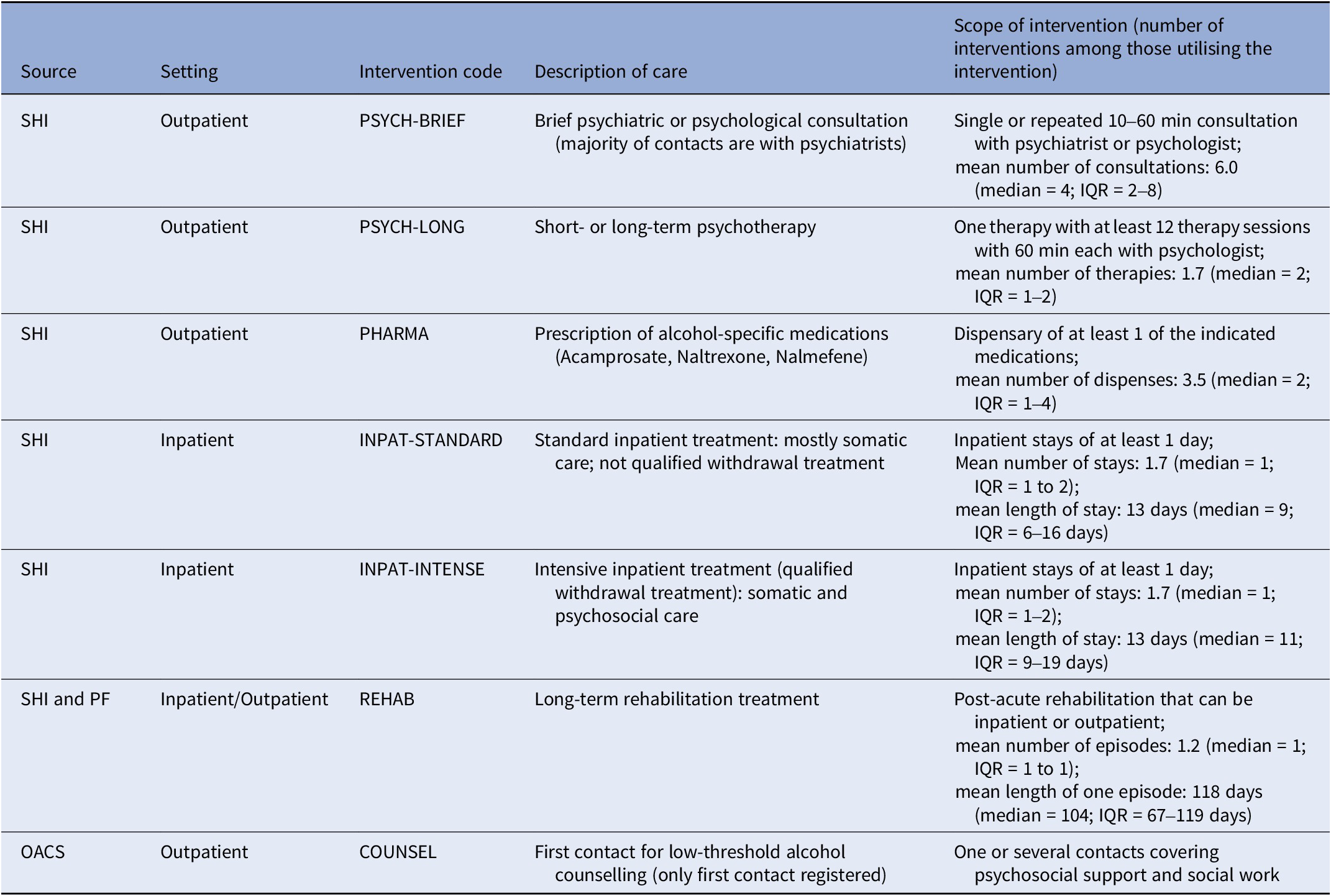

For the present study, we consider seven alcohol-related treatment types, which are described in detail in Table 1. In short, the available data allow us to identify four types of interventions delivered in outpatient settings (PSYCH-BRIEF, PSYCH-LONG, PHARMA, and COUNSEL), two intervention types delivered in inpatient settings (INPAT-STANDARD and INPAT-INTENSIVE), as well as one intervention type delivered in either inpatient or outpatient settings (REHAB).

Table 1. Description of seven treatment types analysed

Abbreviations: SHI, statutory health insurance; PF, pension funds; OACS, outpatient addiction care services.

For four intervention types (PSYCH-LONG, INPAT-STANDARD, INPAT-INTENSIVE, and REHAB), the exact start and end days were available from the data, while only single days of consultations or dispensations were registered for two intervention types (PSYCH-BRIEF and PHARMA). For one intervention type – COUNSEL – the start and end dates of counselling episodes were available, yet some episodes lasted several years during which hardly any contacts may have been made. To avoid assuming that alcohol-related interventions were delivered at any time between the start and end date, only the first contact after the index date was considered and, unlike for other interventions, subsequent contacts were not included due to lack of date information. Also, counselling episodes initiated before the index diagnosis were not considered, as we were interested in the pathway after the index diagnosis.

Sociodemographic information

For each patient, some sociodemographic information is available from the SHI, including time-invariant information on nationality (German, not German/unknown), sex (male/female) as well as the year of birth to calculate age at the time of index diagnosis (similar sized groupings: 18–34; 35–54; 55–64; 65–96 years). Time-varying information on employment/retirement status was grouped into four different categories: employed (including self-employed), unemployed, retired, and other (school, university, refugee, other). Patients were assigned the employment/retirement status that dominated the 12-month look-behind window (i.e., relative maximum in the 12 months preceding the index date).

Comorbidity

To characterise the patient’s health status before their first AUD diagnosis, we relied on diagnostic information from various settings contained in the SHI data set: outpatient medical treatments (general practitioner or specialists, e.g., psychiatrist, cardiologist), inpatient, outpatient surgery (brief surgeries in hospitals), rehabilitation (inpatient or outpatient), or temporary incapacity for work. We used ICD-10 diagnoses registered in these settings during the look-behind period (12 months before the index date) to calculate the Elixhauser comorbidity index [Reference Elixhauser, Steiner, Harris and Coffey18]. Ranging between 0 and 31, a higher Elixhauser score indicates presence of diagnoses in different disease groups (e.g., hypertension, liver disease, drug abuse), that is, a higher comorbidity. Psychiatric diagnoses may only be documented when psychiatric care is accessed, which could introduce a bias in the score. Thus, as done previously [Reference Jemberie, Padyab, McCarty and Lundgren19], we only considered physical comorbidities and removed diagnoses pertaining to alcohol (100% in our sample), drug abuse, psychosis, and depression from the score. The resulting Elixhauser physical comorbidity score has a narrower range (0–27). The distribution of the full score including psychiatric diagnoses is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Statistical analysis

We first identified patients utilising any alcohol-related treatment after a new AUD diagnosis. Among those with treatment utilisation, we conducted latent class analyses (LCAs) to identify treatment utilisation patterns. Seven binary variables indicative of the use of the seven treatment types within 24 months after AUD diagnosis were used as indicator variables in the LCA. Model selection was based on minimising the Bayesian information criterion while ensuring that the smallest class had a sufficient number of members (≥100; for model selection details see Supplementary Table 1).

As class membership probabilities were close 0 and 1 for most patients and classes, patients were distinctly assigned to one of the identified classes based on their maximum posterior class membership probability. To describe each class, we determined a) the dominant intervention type and b) overlaps between treatment types (e.g., INPAT-INTENSIVE and REHAB).

Finally, class assignment was used to describe how patients with different treatment patterns differ in terms of a) sociodemographic information and b) comorbidity. For a), we conducted multinomial regression analyses predicting class membership (categorical variable) with sex, age group, nationality, and employment/retirement status as covariates. For b), we ran zero-inflated negative binomial regressions predicting the Elixhauser physical comorbidity score with sex, age, nationality, and employment/retirement status as covariates in the count model component and sex and age as covariates in the zero-inflation model component. Zero-inflated negative binomial regressions were chosen as optimal models due to the skewed distribution of the comorbidity score (see Supplementary Figure 6).

All analyses were performed in R version 4.2.3 [20], and the LCA was conducted using the R package poLCA [Reference Linzer and Lewis21] version 1.6.0.1. The underlying data cannot be shared due to data protection agreements, but all R codes used to prepare and analyse the data are in the public domain (https://github.com/jakobmanthey/PRAGMA_treatment-patterns/).

Results

Sample description

We identified n = 9,491 patients with an index AUD diagnosis and available information from a subsequent period of 24 months. During the first quarter, 75% of patients received either a F10.1 or F10.2 diagnosis in outpatient settings, while AUD diagnoses in inpatient settings or combinations of AUD diagnoses and settings were rare (see Supplementary Figure 3).

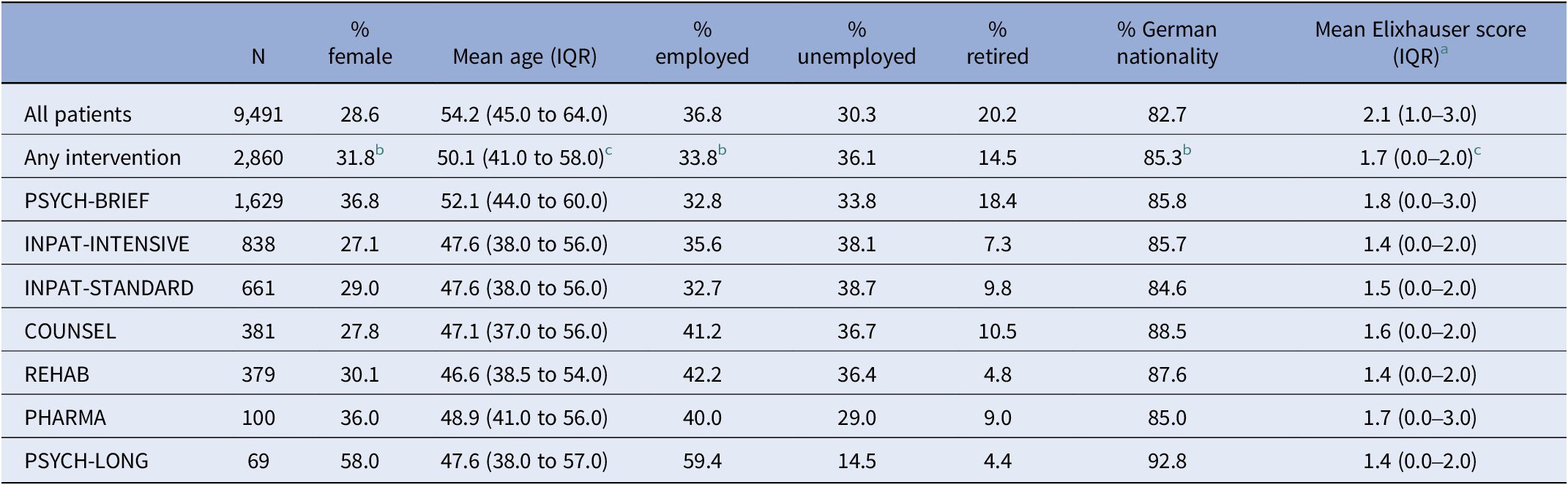

A sample description is given in Table 2. Of all patients, 28.6% were female (71.4%: male), had a mean age of 54.2 years, 36.8% were employed (unemployed: 30.3%; retired: 20.2%; other: 12.7%), and 82.7% had a German nationality. The mean Elixhauser physical comorbidity score was 2.1, that is, the study population had on average two conditions in addition to AUD diagnosed in the 12 months before the index diagnosis. Only 22.6% had an Elixhauser physical comorbidity score of 0, while 43.5% had one or two other conditions diagnosed (sum score 3+: 33.9%). Among those receiving any treatment, a higher share of women, younger, unemployed, and German nationals can be observed. Moreover, the physical comorbidity was on average lower among those utilising any treatment.

Table 2. Description of total sample (first row) and by type of treatment utilised, ordered by number of patients

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

a Only physical comorbidities; possible range: 0–27.

b Significant difference between patients with any versus no intervention; p < 0.001 from χ2 test.

c Significant difference between patients with any versus no intervention; p < 0.001 from t-test.

Treatment utilisation

Overall, 30% (n = 2,860) utilised at least one of the seven treatment options within 24 months of index AUD diagnosis. Brief contacts with psychiatrists or psychologists (PSYCH-BRIEF: 17%) were the most common treatment type, followed by inpatient qualified withdrawal treatment (INPAT-INTENSIVE: 9%) or regular inpatient treatment (INPAT-STANDARD: 7%). A similar proportion of patients were documented to enter rehabilitation services (REHAB: 4%) or to receive low-threshold counselling (COUNSEL: 4%) after index diagnosis. Only very few patients had alcohol-related medications prescribed (PHARMA: 1%) or received formal psychotherapy (PSYCH-LONG: 1%). Among those utilising at least one intervention, 70% utilised only one intervention type (2 types: 20%, 3 types: 8%, 4 or more types: 2%).

Treatment utilisation patterns

Among those utilising at least one intervention (n = 2,860), we identified six classes describing distinct treatment utilisation patterns (% refer to entire sample, see Figure 1):

-

(1) Brief psychiatric care (N = 1,267; 13.3%)

-

(2) Inpatient standard treatment only (N = 255; 2.7%)

-

(3) Inpatient intensive treatment (N = 597; 6.3%)

-

(4) Rehabilitation (N = 366; 3.9%)

-

(5) Counselling (N = 267; 2.8%)

-

(6) Mixed with a high share of pharmacological treatment (N = 108; 1.1%)

Figure 1. Utilisation of seven alcohol-specific treatment options 24 months after new AUD diagnoses for six latent classes. Displayed is the % in each class that utilises a specific treatment option in 3-month intervals. The % in the class label refers to the number of all n = 9,541 patients with a new AUD diagnosis that fall into that class.

In classes 1–5, all patients utilised one intervention type that was also used to label the class (e.g., inpatient intensive treatment in classes 3 and 4). In class 6, the respective patients were typically using multiple interventions of different types. Class 1 is characterised by very low utilisation rates of interventions other than psychiatric brief contacts. Class 2 is distinct from other classes as the only intervention in this class was inpatient standard treatment. Classes 3 and 4 are characterised by all patients utilising inpatient intensive treatment and rehabilitation, respectively. While 54% of patients in class 4 (rehabilitation) also utilise inpatient intensive treatment, rehabilitation is not used by any patient in class 3 (inpatient intensive treatment). In both classes 3 and 4, inpatient standard treatment is utilised by about one in four patients. Class 5 is characterised by all patients seeking low-threshold counselling support, while 23% also utilised brief psychiatric consultations and 15% entered inpatient standard treatment. Finally, class 6 is characterised by very high rates of pharmacological treatment (92%) and brief psychiatric care (62%), but all other interventions are also utilised in this group (utilisation rates: 6–39%).

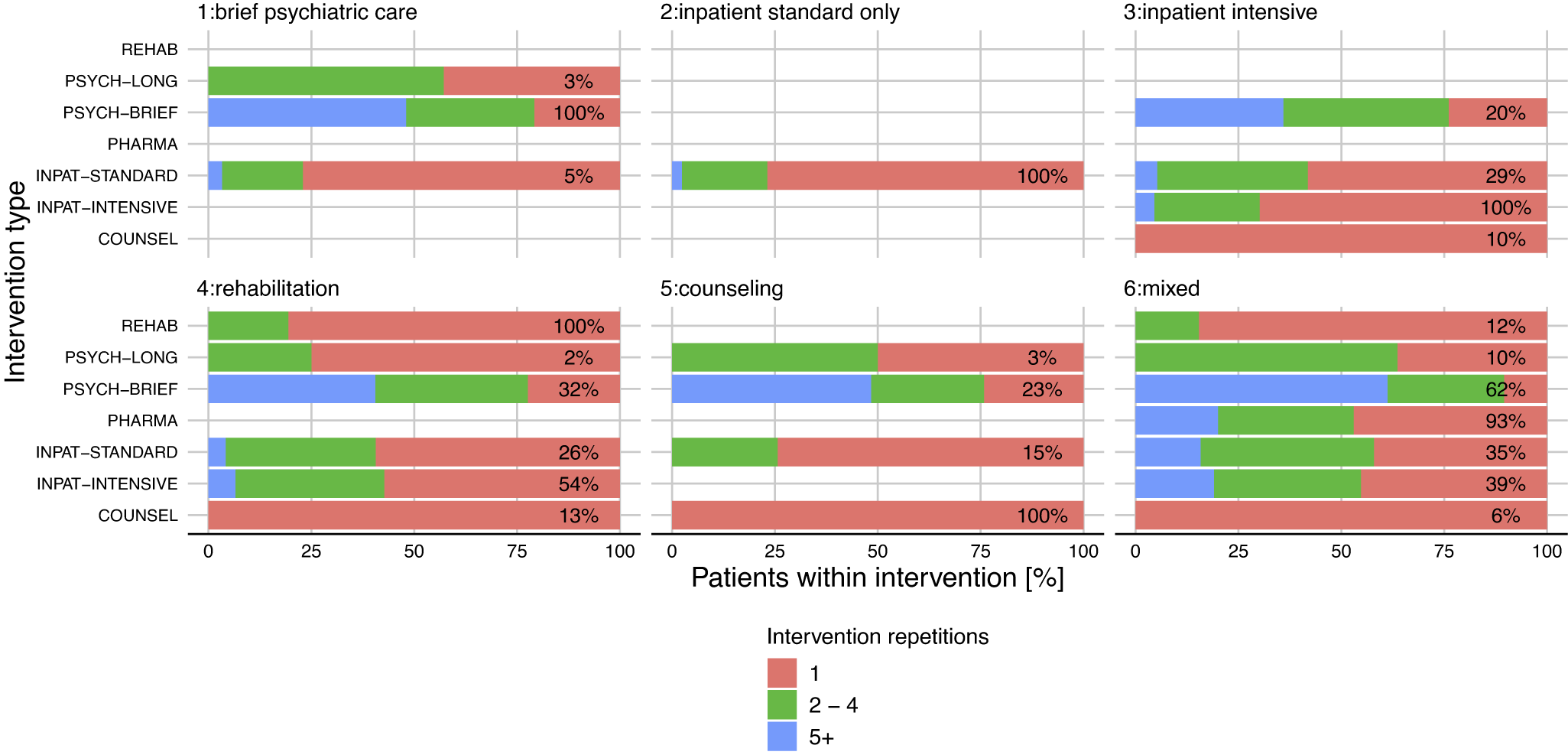

The intensity of each treatment was operationalised by the number of interventions utilised among those utilising at least one intervention of each type (see Figure 2). Across all latent classes, brief psychological consultations were utilised more than once by most patients, while most other intervention types were typically used only once. Class 6 was not only characterised by utilisation of various treatment types but also by on average more frequent utilisation of each treatment type. To which degree various treatment types were utilised by the same person within each class is shown in Supplementary Figure 2. Most people utilised only one treatment type, but high overlaps are observed in classes 4 (“rehabilitation”) and 6 (“mixed”) – those classes characterised by presence of multiple intervention types.

Figure 2. Intensity in utilisation of seven different treatment options within 24 months after first AUD diagnosis for six latent classes. On each bar, the percentage displays how many individuals in each class have utilised the respective intervention type, while the bar itself displays how often each intervention type was utilised within each class. For example, 54% of the rehabilitation class (#4) have used intensive inpatient treatment, and among these persons, the percentage of 1, 2–4, and 5 or more inpatient stays was 57.3%, 36.2%, and 6.5%, respectively.

Treatment utilisation patterns, baseline diagnoses, and sociodemographics

We explored whether treatment utilisation patterns are related to AUD diagnosis and setting recorded during the index quarter. Single F10.1 or F10.2 diagnoses in outpatient settings were more common among those seeking no treatment (class 0: 82.3%) as well as in classes 1 (brief psychiatric care: 77.3%) and 5 (counselling: 72.7%). In classes 2, 3, 4, and 6, a considerably higher share of inpatient AUD diagnoses at index quarter was observed (see Supplementary Figure 3).

With multinomial regression analyses, we investigated how age, sex, nationality, and employment/retirement status were linked to treatment utilisation patterns (model results: Supplementary Table 2 ; illustrations: Supplementary Figures 4 and 5). Compared to no treatment, every treatment utilisation pattern was linked to younger age. The classes 1 (brief psychiatric care), 4 (rehabilitation), and 6 (mixed) had statistically significantly higher shares of women than the no-treatment group. A higher share of German nationals was recorded in classes 1 (brief psychiatric care) and 3–5 (inpatient intensive, rehabilitation, counselling). Compared to employed patients, those unemployed had higher odds of utilising brief psychiatric care (class 1), inpatient standard treatment only (class 2), and inpatient intensive treatment (class 3). Those in retirement were more likely to receive brief psychiatric care (class 1) but less likely to receive rehabilitation treatment (class 4).

Treatment utilisation patterns and physical comorbidity score

The skewed distribution of the Elixhauser physical comorbidity scores is shown in Supplementary Figure 6. Most patients have 0 or 1 condition diagnosed in addition to AUD, while only a few patients have more than five conditions diagnosed. Compared to no treatment utilisation and controlling for differences in sex, age, employment/retirement status, and nationality, patients in classes 1–4 (brief psychiatric care, inpatient standard, inpatient intensive, rehabilitation) had statistically significantly lower comorbidity scores before their index AUD diagnosis. Specifically, the mean Elixhauser physical comorbidity scores were 8%, 17%, 16%, and 17% lower in classes 1–4, respectively (results see Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

Summary

This study investigated the utilisation of various alcohol-related treatment options in Hamburg, Germany, 24 months after an index AUD diagnosis. Relying on electronic health records of about 9,500 patients residing in the between 2016 and 2021, we find that only 3 in 10 patients utilised at least one treatment option. Brief consultations with psychiatrists or psychotherapists constitute the most frequently utilised treatment type, followed by intensive and standard inpatient (withdrawal) treatment, as well as post-acute rehabilitation treatment and low-threshold outpatient counselling. Alcohol-related pharmacotherapy and formal psychotherapy were very rarely utilised. The findings further suggest that treatment types are often not combined, except for rehabilitation treatment, which is often preceded by intensive inpatient treatment (qualified withdrawal, see also [Reference Manthey, Lindemann, Kraus, Reimer, Verthein and Schulte22]). Overall, people utilising alcohol-related treatment after their AUD diagnosis are more likely to be younger, and some treatment patterns are more prevalent among women and unemployed patients, and among patients with less physical comorbidity.

Limitations

We need to acknowledge three areas limiting the interpretation of our findings. First, by analysing electronic health records, we rely on the information documented for administrative and reimbursement purposes. For example, the diagnostic information may not be complete as some conditions may only be recognised by certain professionals and require in-depth (medical) assessments. By applying strict inclusion criteria and adhering to treatment definitions applied in previous studies (e.g., [Reference Mockl, Manthey, Murawski, Lindemann, Schulte and Reimer16]), we sought to minimise any biases inherent in the data. This specifically concerned psychiatric comorbidities, which were excluded from the data altogether and thus limits the assessment of comorbidity to physical conditions.

Second, we only had access to 6 years of data, which limited the look-behind window to 12 months for determining the index AUD diagnosis date. We cannot rule out that some patients had been diagnosed with AUD more than 12 months before the index date and may have even utilised alcohol-related treatments. As previous treatment experiences may influence current treatment utilisation behaviour, this unmeasured confounder constitutes a possible bias that we cannot control for.

Third, we were unable to consider all types of treatment available for people with AUD in Germany. While we have taken into account major treatment types recommended by the national guidelines [Reference Kiefer, Batra, Petersen, Ardern, Tananska and Bischof9], several services considered to be integral parts of the German addiction care system were not included in our analyses, such as integration assistance (“Eingliederungshilfe”), self-help groups, occupational support, and services offered in the judiciary system [Reference Bürkle, Fleischmann, Koch, Leune, Raiser and Ratzke23]. Further, due to not being explicitly reimbursed, brief interventions in PHC settings could not be identified in the data, but surveys suggest that delivery rates of brief interventions in Germany are low [Reference Kastaun, Garnett, Wilm and Kotz24, Reference Frischknecht, Hoffmann, Steinhauser, Lindemann, Buchholz and Manthey25]. Generally, we cannot gauge how many people with diagnosed AUD utilised treatment types other than those analysed in this study. It appears unlikely that we have missed important treatment types; thus, we believe that our findings overall are an accurate representation of reality in Hamburg. In rural areas, however, treatment utilisation may differ due to variations in treatment availability.

Implications

The findings suggest that 7 out of 10 patients with a diagnosed AUD do not utilise any alcohol-related treatment as defined in our study. Given that some of the treatments, for instance psychiatric consultations, might not have focussed solely on AUD but on other psychiatric conditions, this might even be an underestimation. Previous studies have already demonstrated the low treatment utilisation among people with AUD in the general population [Reference Mekonen, Chan, Connor, Hall, Hides and Leung12]. Our study completes that picture by demonstrating that very low treatment rates are also observed among those already recognised in the healthcare system. In other words, most people receiving an AUD diagnosis in PHC or other healthcare settings are not effectively referred to specialists and do not receive adequate care. To explain suboptimal care, patient-level and provider-level perspectives need to be considered.

For the patient, the AUD diagnosis may not be the primary reason for a healthcare visit. The higher comorbidity score among those not utilising alcohol-related treatments could be interpreted as many patients prioritising the management of other, perhaps more impairing conditions like liver disease or chronic pulmonary diseases. Importantly, heavy alcohol use is a risk factor for most of the identified physical comorbidities [Reference Rehm, Gmel, Gmel, Hasan, Imtiaz and Popova26], thus ignoring that untreated AUD may result in suboptimal care for those conditions. Those willing to enter specialist AUD treatment will encounter further barriers, for example, stigmatisation [Reference Kilian, Manthey, Carr, Hanschmidt, Rehm and Speerforck27], limited knowledge of treatment options [Reference Wallhed Finn, Bakshi and Andréasson28], long waiting times for withdrawal, and post-acute rehabilitation treatment [Reference Buchholz, Spies, Härter, Lindemann, Schulte and Kiefer29]. The higher unemployment rates among people entering specialist treatment in our study may indicate that current employment constitutes a barrier to entering treatment as it is incompatible with certain treatment types.

Optimal treatment provision may be further complicated by the very fragmented treatment system in Germany. While we linked three major data sources to give a comprehensive account of alcohol treatment services, however, we could not consider all possible treatments. From both a patient and a healthcare provider perspective, the complex treatment system can be perceived as a barrier. To navigate through the healthcare system is a core aspect of alcohol health literacy and requires training or comprehensive experiences. Surveys of PHC providers suggest that they are ill-prepared, indicated by low knowledge of existing guidelines and insufficient time to deal with AUD [Reference Buchholz, Spies, Härter, Lindemann, Schulte and Kiefer29] as well as lack of postgraduate training on alcohol-related topics [Reference Kraus, Schulte, Manthey and Rehm30]. Finally, AUD remains a stigmatised condition that impedes optimal care on various levels, including but not limited to the patient–clinician relationship and allocation of resources [Reference Schomerus, Leonhard, Manthey, Morris, Neufeld and Kilian31].

Importantly, we find that a substantial share of people with AUD is in regular contact with psychiatrists – a pattern we have not seen in previous studies on this subject. The available data do not allow for an extensive characterisation of the treatment provided, except that medications specific to AUD were rarely prescribed. Further research investigating patient perspectives on consulting psychiatrists versus general practitioners can help to tailor treatment options according to personal preferences. It should be explored to which degree brief interventions are contained in psychiatric consultations. As the efficacy of brief interventions for severe AUD may be limited [Reference Saitz32], more extensive interventions may be required for many people with AUD in regular contact with psychiatrists.

Finally, it should be noted that among those utilising alcohol treatments, usually one type of treatment is utilised and only a few people combine various treatment types. One notable exception is inpatient intensive treatment followed by post-acute rehabilitation treatment. This cascade of care is a core recommendation in the national guidelines [Reference Kiefer, Batra, Petersen, Ardern, Tananska and Bischof9], but only very few patients were documented to follow this pathway. Surprisingly, brief consultations with psychiatrists or psychotherapists appear to be an important treatment option that has hardly gained any scientific attention to date. Addiction-specific training of psychiatrists, for example, in giving alcohol brief advice, could improve care provision. Unlike brief consultations, SHI-reimbursed formal psychotherapy requires patients to be abstinent within 10 sessions [33]. Thus, brief consultations appear to be the more accessible treatment option. However, further research is required to understand the actual care delivered in this format. Possibly, the brief consultations identified in our study focus on psychiatric conditions other than AUD, which may be one reason why the prescription of pharmacological interventions to reduce craving and maintain abstinence was so rarely recorded in our study. Given the compelling evidence of pharmacotherapy for AUD [Reference Heikkinen, Taipale, Tanskanen, Mittendorfer-Rutz, Lahteenvuo and Tiihonen34], the observed very low prescription rates constitute perhaps the most pronounced healthcare provision gap. According to estimates for 2004, increasing the coverage of AUD patients in pharmacological treatment can delay up to 10,000 deaths within 1 year [Reference Rehm, Shield, Gmel, Rehm and Frick35].

Conclusion

This data-linkage study offers a novel approach to understanding the real-world utilisation of alcohol-related treatment options after a first AUD diagnosis in the fragmented German healthcare system. Our findings demonstrate that treatment pathways mostly contrast with national guidelines. The majority of patients diagnosed with AUD do not receive adequate care, with possibly detrimental effects on other psychiatric or physical conditions. Minimising structural and social barriers is not only required to ensure optimal healthcare provision for those affected but also to reduce the overall societal burden attributable to alcohol use.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2025.8.

Data availability statement

The underlying data and R codes are publicly available (https://github.com/jakobmanthey/PRAGMA_treatment-patterns/).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the data owners (AOK Rheinland/Hamburg – Die Gesundheitskasse; DAK – Gesundheit, Deutsche Rentenversicherung Nord, Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund, and BADO e.V.) as well as Fabian Zambasi for plausibility checks and anonymisation procedures.

Author contribution

Conceptualisation: JM; Methodology: JM and KH; Software: JM and KH; Validation: JM, SB, BS, and LK; Formal analysis: JM and KH; Investigation: all authors; Resources: JM and BS; Data curation: JM and KH; Writing – original draft: JM, BS, and LK; Writing – review & editing: all authors; Visualisation: JM and KH; Supervision: JM; Project administration: BS; Funding acquisition: JM and BS.

Financial support

This publication is based on the project “Patient Routes of People with Alcohol Use Disorder in Germany” (PRAGMA), which was funded by the Innovation Committee of the Federal Joint Committee (Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss, GBA) under the funding code 01VSF21029. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, or preparation of this publication.

Competing interest

Unrelated to the present work, JM has worked as consultant for and received honoraria from various public health agencies. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.