Increasing recognition of the effect of brain disorder on mental health and insights into the indelible inseparability of mind and body (Reference Yudofsky and HalesYudofsky & Hales, 2002) have contributed to a growing interest in neuropsychiatry. This interest has been fuelled by the arbitrariness of the historical separation of neurology and psychiatry, and recognition of the growing overlap between the two, with advancement of scientific knowledge. In the UK, early identification and management of cognitive, behavioural and mood symptoms in people with neurological disorders, in the true Meyerian tradition of psychobiology (Reference LidzLidz, 1966), is now an important quality requirement of the National Service Framework for long-term conditions (Reference Agrawal and MitchellAgrawal & Mitchell, 2005; Department of Health, 2005).

Yet, the current map of neuropsychiatry service provision in the UK is still not clear. Traditionally, such services have been provided at a few regional or national centres and users were expected to travel long distances for a neuropsychiatrist's opinion. This is very much against the ideals of integrated, interdisciplinary and easily accessible neuropsychiatry services (Department of Health, 2005). Geographic distance to accessible neuropsychiatry services has been found to be associated with unmet need (Reference Fleminger, Leigh and McCarthyFleminger et al, 2006). This highlights the need for reasonably local neuropsychiatry services with clear referral pathways.

Nationally, there is a dearth of information about neuropsychiatry services, their referral pathways and funding streams. There have been a few papers on individual neuropsychiatry services or a group of services in the UK (Reference Leonard, Majid and SivakumarLeonard et al, 2002; Reference Barrett and SudharsanBarrett & Sudharsan, 2005; Reference Fleminger, Leigh and McCarthyFleminger et al, 2006), but they do not provide a coherent national picture.

Hence, the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Special Interest Group in Neuropsychiatry decided to survey College members who had expressed an interest in neuropsychiatry, to obtain information on current neuropsychiatry service provision, including staffing levels, services provided, their setting, referral pathways and funding streams. Our aim was to use this information to inform neuropsychiatry service development in the UK.

Method

A questionnaire was developed by a working group of the Special Interest Group in Neuropsychiatry. This was posted to 508 College members by the audit department of South West London and St George's Mental Health Trust on behalf of the Group. An envelope was included for the reply and an additional sheet of paper was enclosed to allow the trainees, who may have felt they were not responsible for providing any services, to respond. The members were mailed after 4 weeks to encourage response from those who did not answer the initial letter. All the responses were collated and entered on to an SPSS database and analysed with the help of the Trust's audit department.

Results

A total of 251 members (49.4%) replied to the survey: 161 (64.1%) after the first mailing and a further 90 (35.9%) following second mailing. Some trainees who were not responsible for providing a neuropsychiatry service answered by telephone, as the questionnaire did not apply to them.

Of the 251 respondents, 70 reported (27.9%) that they were responsible for providing some degree of neuropsychiatry service. The rest (n=181), who felt that the survey did not apply to them, included trainees (35.1%), members who had an interest in but were not responsible for providing any neuropsychiatry service (30.4%), and others (32.1%). This latter group included ‘addressee not known or moved’ or questionnaire returns without stating a reason. Only a small proportion of the respondents (2.6%) reported no interest in neuropsychiatry.

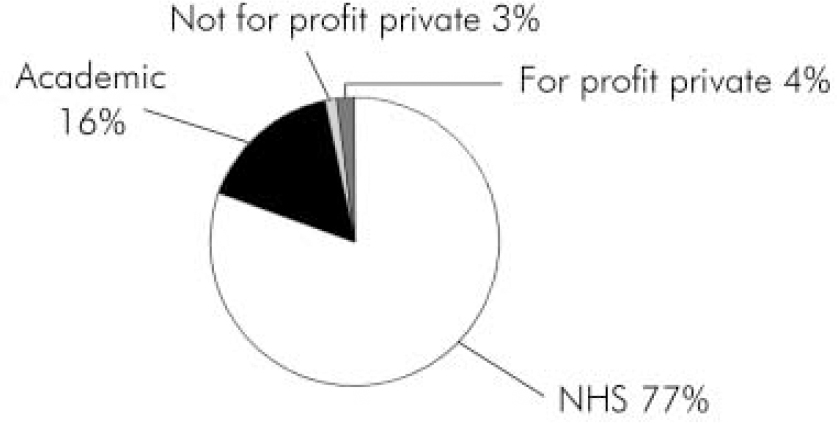

In our analysis we focused on 70 respondents who reported being responsible for or providing some neuropsychiatry services. The vast majority of these (77%) were National Health Service (NHS) consultants, a small number were academics (16%) and a few (7%) worked in the private sector (Fig. 1).

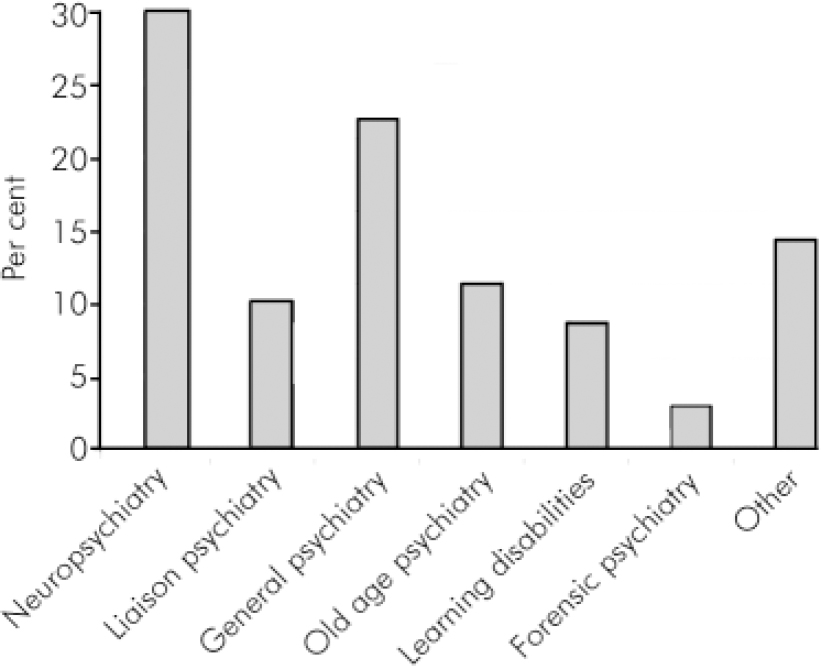

Only 21 of these respondents (30%) were principally employed as neuropsychiatrists. The rest had a range of principal employments in various psychiatric subspecialties (Fig. 2). However, the great majority of these nevertheless provided at least 1–2 sessions worth of neuropsychiatry input.

Of those who were principally employed as a neuropsychiatrist (n=21), similar proportions were working in the NHS sector and had academic jobs as in Fig. 1. Over half (52.4%) of the neuropsychiatrists were working full-time in clinical neuropsychiatry – one in five did 6–9 sessions and about a quarter did 3–5 sessions. Part-time neuropsychiatrists were either doing split clinical jobs with other psychiatric subspecialties (30%) or academic jobs (40%), with the rest not specifying.

A wide range of neuropsychiatry services (defined as those employing a neuropsychiatrist) were offered (Table 1). The most common of these were out-patient services and specialist clinics. Over half (61.9%) had in-patient beds. Community nursing was only rarely available as a part of neuropsychiatry service. Most of the services covered a wide range of neuropsychiatry areas. The most common of these were brain injury, memory and epilepsy clinics (Table 2).

Table 1. Neuropsychiatry services provided by the 21 neuropsychiatrists1

| Type of services | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Special interest clinic | 12 (57.1) |

| General hospital liaison psychiatry | 10 (47.6) |

| Specialist neuropsychiatry service | 18 (85.7) |

| Out-patient service | 19 (90.5) |

| Neuroscience liaison psychiatry | 13 (61.9) |

| Day patients | 7 (33.3) |

| Community nursing | 5 (23.8) |

| In-patient beds | 13 (61.9) |

Table 2. Areas covered by neuropsychiatric services provided by the 21 neuropsychiatrists1

| Type of conditions | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Brain injury | 20 (95.2) |

| Epilepsy | 19 (90.5) |

| Movement disorder | 13 (61.9) |

| Cognitive and memory disorder | 17 (81.0) |

| Sleep disorder | 12 (57.1) |

| Liaison psychiatry | 15 (71.4) |

| Neuropsychiatry of developmental disorder | 15 (71.4) |

| Neurological unexplained symptoms | 13 (61.9) |

| Other | 3 (14.3) |

Of the 21 doctors who were principally appointed as neuropsychiatrists, over 70% of the neuropsychiatry services had existed for more than 10 years, 5% for more than 5 but less than 10 years and the rest had been developed within the last 5 years. Although 52% of the services had expanded in the last 5 years (including the ones which were developed in this period), 38% remained unchanged and 10% were forced to reduce in size.

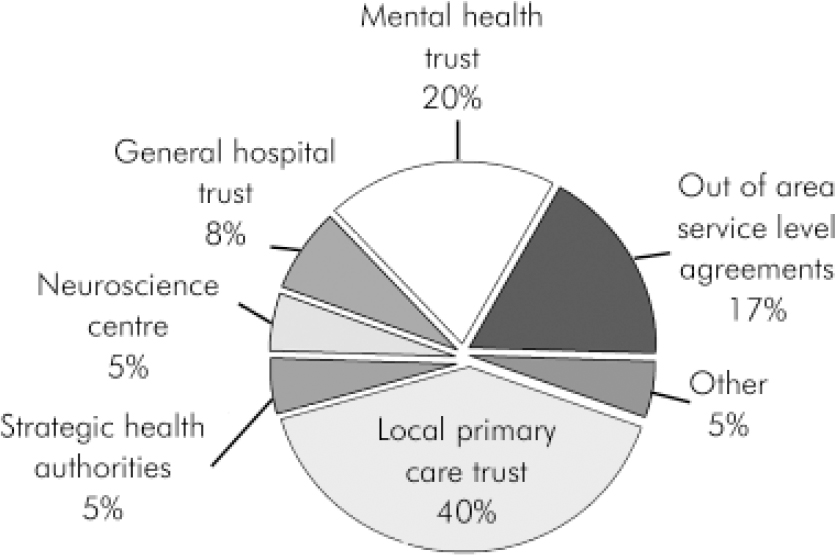

Over half of the services were principally based in teaching hospitals (56%); the rest were based in brain injury rehabilitation units (14%), regional neurosciences centres (10%), district general hospitals (10%), and other settings (10%). The sources of funding of the services varied widely (Fig. 3). Three-fourths of the funds was, however, channelled through mental health trusts.

The majority of neuropsychiatry services accepted referrals from a wide range of sources (Table 3), including psychiatrists, neuroscience clinicians (neurologists, neurosurgeons, neuropsychologists, etc.) and specialist units such as brain injury rehabilitation centres. Despite the perceived tertiary nature of neuropsychiatry, three-quarters of the services accepted referrals from primary care.

Table 3. Referral pathways (N=21 neuropsychiatrists)

| Sources of referrals | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Neuroscience clinicians | 18 (85.7) |

| General practitioners | 16 (76.2) |

| Psychiatrists | 19 (90.5) |

| Other general hospital consultants | 17 (81.0) |

| Specialist units | 12 (57.1) |

Fig. 1. Type of employment (n=70).

Fig. 2. Clinical field of principal employment (n=70).

Discussion

This is the first national survey of its kind. It focused on the members of the Royal College of Psychiatrists with interest in neuropsychiatry. Although it is possible that some psychiatrists who provide neuropsychiatry services may not have registered an interest, for the purpose of the study we assumed it is unlikely that clinicians principally employed as neuropsychiatrists will not have done so. The rate of response to our survey was consistent with other postal surveys. A high number of trainees and other clinicians expressing interest in neuropsychiatry reflects the growing interest in this specialty. This needs to be fostered and a clear neuropsychiatry training programme has to be provided to meet their needs (Reference Mitchell and AgrawalMitchell & Agrawal, 2005).

Fig. 3. Sources of funding (n=21 neuropsychiatrists).

We found that there were 21 consultants who were principally employed as a neuropsychiatrist in the UK. This number is consistent with the number of neuropsychiatrists known to our interest group. The majority were based in a few major regional, national or teaching hospitals. This confirms the patchy nature of current neuropsychiatry service provision.

A range of psychiatric consultants currently provide some degree of neuropsychiatric input, mostly in the form of 1–2 special interest clinics a week. Out of the 21 consultants who were employed as neuropsychiatrists, about half were devoting all their sessions to clinical neuropsychiatry and most of the rest devoted 3–9 sessions to clinical work. They provided a wide range of neuropsychiatry services, including a number of specialist neuropsychiatry clinics. Referrals were accepted from primary, secondary or tertiary services. Hence, where the neuropsychiatry services existed, they provided a reasonably comprehensive service. However, in-patient neuropsychiatry beds were not commonly available.

One of the most worrying aspects identified was that of the two-thirds of neuropsychiatry services that had existed for more than a decade, a significant proportion had not expanded in recent years and a significant number was forced to reduce in size. This occurred at a time when neurological and psychiatric services went through an unprecedented expansion and the overall numbers of consultants increased in the UK by over 70% (Department of Health, 2004). This could possibly be attributed to the predominant focus of national service framework for mental health (Department of Health, 1999) on providing comprehensive community services. The wide range of funding sources of existing neuropsychiatry services indicate a lack of coherent funding and commissioning arrangements. This can again be a factor contributing to the lack of appropriate neuropsychiatry service development in the UK.

In conclusion, neuropsychiatry services in the UK are currently based in a few regional centres. This represents a grossly inadequate service provision. Although some other psychiatric specialists try and fill in the gap with the help of special interest clinics, this can not be a reliable way to meet the population need. Neuropsychiatry service development seems to have lagged behind other psychiatric and neuroscience services significantly over the past decade. Lack of clarity of funding streams, commissioning arrangements, and appropriate guidelines about what would constitute an adequate neuropsychiatry service could be contributing to this limited and currently inequitable service provision.

Declaration of interest

S.F. is the lead consultant neuropsychiatrist for two brain injury units which both require primary care trusts to authorise in-patient admissions and out-patient appointments.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Audit Department of the South West London and St George's Mental Health Trust at Springfield Hospital which provided substantial help and support. In particular, we thank Ms Liz Collins, Ms Jane Dunnell and Ms Grace Chew.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.