Contemporary China represents one of the most restrictive environments for religion and religious groups around the globe (Fox, Reference Fox2008; Majumdar and Villa, Reference Majumdar and Villa2021; Office of International Religious Freedom, 2021). This is not by accident, but by design. Since coming to power in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has promoted state atheism, viewed religion as a “spiritual opium” and instrument of imperialism, and operated under the assumption that religious life will wither away as socialism advances (Dunch, Reference Dunch and Yang2008; Yang, Reference Yang2012). To encourage the waning of religion, strict parameters on religious belief and behavior have been put in place, including restricting ritual and worship to government-registered sites, requiring clergy to study in state-sanctioned schools for religious training, and recognizing only five religions—Buddhism, Daoism, Islam, Protestantism, and Catholicism. To bring religious communities under the influence of the party-state, Chinese Catholics are expected to be independent from the Vatican, and official Protestants should have no denominational affiliations.Footnote 1 Muslims must receive government approval to participate in the hajj,Footnote 2 and Chinese government authorities oversee the succession of living Buddhas for Tibetan Buddhism (CECC, 2007; Kuzmin, Reference Kuzmin2017). The reach of the Chinese state into religious life is extensive.

This article examines the shifting strategies used to restrict and regulate Christianity in contemporary China. We argue that these strategies of control have developed and evolved within a highly securitized environment for religion, which elevates religion to an issue of national importance and potential threat, and thus justifies the expansion of party-state control.Footnote 3 China's securitization of religion is distinctive in that it is both long-term and evolving. While securitization efforts in other countries often follow exogenous shocks and result in measures to contain national security crises, the process in China spans decades. Since coming to power, the CCP has viewed religion in general and Christianity in particular as a long-term, existential threat. Christianity is not only an ideological competitor for the communist party, but Catholics and Protestants tend to be stigmatized as foreign faiths and associated with Western aggression. As such, they are viewed as vehicles for foreign influence and potential subversion because of their transnational linkages, the global prominence of Christianity, and, especially for Catholics, the ecclesiastical authority of the Vatican. Further feeding into fears of Christianity's subversive potential, is the fact that churches are some of the largest and fastest growing forms of associational life in China, with many worshiping in unregistered churches outside of government control (Bays, Reference Bays2003; Xin, Reference Xin2009; Madsen, Reference Madsen2010; Koesel, Reference Koesel2013; Yang, Reference Yang2016). Some estimates suggest that Christian communities will grow to 265 million by 2030—meaning Christians will likely outnumber communist party members by more than 2:1 (Stark and Wang, Reference Stark and Wang2015).Footnote 4

We argue that these and other evolving concerns have sustained China's highly securitized environment for Christians and led to a range of policies and practices to exercise party-state control over churches. These strategies are both multi-dimensional and additive. They target different aspects of Christian life and build on one another to increase government oversight. Underlying these evolving strategies of control is the goal to ensure fealty to the CCP.

What follows advances this argument with a comparison of official Catholics and Protestants in China.Footnote 5 Specifically, the analysis begins by unpacking the highly securitized environment for Christians in China and the strategies of control that undergird it. Next, we draw on textual analysis of course materials used in state-sanctioned seminaries to illustrate how clergy are taught the “correct” understanding of church–state relations, reverence for the CCP, and the threat of external forces. The textbooks analyzed are written and vetted by regime representatives and, thus, provide new insight into how the party-state attempts to convey political knowledge to future religious leaders and influence them at the micro-level. The patterns we uncover demonstrate strikingly consistent efforts to favorably orient clergy toward the CCP, as the protector of China and Chinese Christians. The analysis then turns to the hardening of strategies under Xi Jinping. Here, we survey recent shifts in religious policy that restrict Christian communities with a focus on recent efforts to Sinicize (中国化) Christians. We compare the Sinicization plans of official Catholic and Protestant churches as well as local churches' Sinicization efforts and show the integration of political ideology over traditional culture and values. Sinicization in practice, thus, places politics and the Party at the center of churches and represents new efforts to domesticate Christianity. The conclusion returns to key findings, discusses implications for religious groups navigating restrictive political environments, and offers some reflections on the securitization of religion in China.

Securitization of religion

Securitization theory provides a useful framework for understanding the Chinese management of religious life and the growing reach of the party-state into religion and ritual. Security is about survival and securitization theory, in its most basic form, lays out the process by which an issue is elevated to the level of national importance to justify extraordinary state action (see, e.g., Buzan et al., Reference Buzan, Wæver and de Wilde1998; Buzan and Wæver, Reference Buzan and Wæver2003; Williams, Reference Williams2003; Gad and Petersen, Reference Gad and Petersen2011). The securitization process begins with political actors, typically leaders and elites but also media and other cultural influencers, deliberately naming and framing an issue as an existential threat to the nation, state, or economy in order to advance policies and procedures to contain or block the perceived threat (Wæver, Reference Wæver and Lipschutz1995, 55; Buzan et al., Reference Buzan, Wæver and de Wilde1998, 21–23, 241; Laustsen and Wæver, Reference Laustsen and Wæver2000, 708; Wæver, Reference Wæver2011). Successful securitization, thus, rests on the ability of regime representatives to present an issue in such a way that it persuades multiple audiences and advance policies and procedures outside of conventional politics (Cesari, Reference Cesari2012, 433). As Buzan et al. (Reference Buzan, Wæver and de Wilde1998, 21, 19) explain, “the invocation of security has been the key to legitimize the use of force, but more generally it has opened the way for the state to mobilize, or to take special powers to handle existential threats” until the threat is de-securitized and returns to the ordinary public sphere.

In practice, securitization occurs in both democracies and non-democracies as state representatives attempt to elevate concerns to that of a national emergency. While authoritarian leaders generally have a securitization advantage because they operate with fewer constraints, can manipulate the media, and are less dependent on public opinion than democratically elected leaders, autocrats nevertheless make efforts to frame issues as national threats in order to take preemptive action (but also see Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson2007; Koesel and Bunce, Reference Koesel and Bunce2013; Dukalskis, Reference Dukalskis2017). Viktor Orbán, for instance, securitized population decline in Hungary to mobilize support for pro-family policies that provided free fertility treatments, subsidies for large-passenger vehicles, and income tax exemptions for mothers with four or more children (Judah, Reference Judah2021). In Turkey, Erdoğan securitized opposition groups by “framing them as collaborators of sinister foreign powers who want to destroy their country and the Turkish nation,” a move that also justified further centralization of power (Yilmaz and Shipoli, Reference Yilmaz and Shipoli2021, 11).

One of the clearest examples of the securitization of religion occurred following 9/11, when a number of countries took steps to securitize Islam (Buzan, Reference Buzan2007). In democracies, this prompted debates about “good” versus “bad” Muslims that conflated Islam with violence and led to expanded government oversight over Islamic life (Mamdani, Reference Mamdani2002; Jackson, Reference Jackson2007; Downing, Reference Downing2019). These policies also increased discrimination (Fox and Akbaba, Reference Fox and Akbaba2015), racial profiling (Cole, Reference Cole2003), and restrictions on the civil liberties and religious freedom of Muslims (Mabee, Reference Mabee2007; Cesari, Reference Cesari2012). In autocracies, the securitization of Islam also fostered discrimination, such as the disproportionate linking of Muslims to extremist and terrorist organizations in Russia (Arnold, Reference Arnold2016; Laruelle, Reference Laruelle2021, 12) and discrediting Islamic political parties in Malaysia, a main competitor of the incumbent government (Rabasa, Reference Rabasa, Rabasa, Bernard, Chalk, Fair, Karasik, Lal, Lesser and Thaler2004, 51). At the same time, the global war on terror helped authoritarian governments justify the use of selective, and often repressive, measures against Muslim populations (Tschantret, Reference Tschantret2018; Potter and Wang, Reference Potter and Wang2022, 359). Securitization of Islam, therefore, opened the door for authoritarian leaders to take violent and preemptive measures against perceived religious threats.

The securitization of Christianity in China

In China, Christianity has always been at odds with the party-state and the securitization of religion began as the CCP rose to power. Viewed through the lens of Marxism–Leninism, Christianity was seen as an impediment to the advancement of socialism, a spiritual opium that kept the masses submissive, and a tool used by foreign forces to weaken China (Lenin, Reference Lenin1905; Mao, Reference Mao1949; He, Reference He1955). For the new communist regime, Christianity needed to be “secured.” Chinese Catholics and Protestants were viewed with particular scrutiny, if not hostility, because of their strong foreign ties and outspoken religious leaders, such as Pope Pius XII who was a vocal critic of communism and the Chinese regime's treatment of Catholics (Madsen, Reference Madsen, Kindopp and Hamrin2004). Christianity was also inextricably linked to imperialist aggression. To communicate these concerns, a letter signed by over 1,500 Protestant leaders sympathetic to the new regime appeared in the People's Daily—the mouthpiece of the CCP. The Protestant leaders called on Christians to “eliminate the influence of imperialism within Christianity” and to work toward building a New China under the leadership of the new government (Wu et al., Reference Wu1950). The letter also cautioned believers to be vigilant against imperialists seeking to exploit them and sow domestic discord or cultivate reactionary forces in China (Wu et al., Reference Wu1950; Wickeri, Reference Wickeri1998, 130). Other newspapers echoed these concerns. Christian missionaries and some clergy were denounced as foreign intelligence agents who aligned with Chinese feudal landlords as well as Japanese and American aggressors to deceive and oppress “good [Chinese] people” and challenge communism (FBIS, 1950b; Wu, Reference Wu1950; Xinhua, 1952). Party leaders, therefore, did not need to go to great lengths to justify the securitization of Christianity, beyond that it was antithetical to revolutionary goals and linked to imperialist aggression against China.

Chinese Catholics and Protestants also presented practical challenges for the new regime that hastened the need to secure churches. Christianity provided a value system that competed with Marxism–Leninism and Christians recognized an authority that transcended the party-state. Although Chinese Christians were less than one percent of the population in 1949, they nevertheless represented a foreign source of allegiance, and the CCP did not want a competing moral vanguard (Chan, Reference Chan2019, 18). Christian communities were additionally endowed with resources—or in Leninist terms organizational weapons—that made them particularly good at political mobilization, and therefore, a potential threat. They had tightly knit networks that bridged social and geographic cleavages, transnational linkages and allies, regular sources of funding, brick-and-mortar buildings, and charismatic leaders with devoted followers (Smith, Reference Smith1996; Koesel, Reference Koesel2014). Party leaders needed only to look to Chinese history for evidence of homegrown religious rebellions with Christian overtones, such as the Taiping rebellion, to further justify the securitization of Christianity.

For the CCP, religion in general, and Christianity in particular, was an existential threat that needed to be secured. Catholics and Protestants were seen as foreign faiths, linked to imperialist aggression and susceptible to hostile foreign influence; they were also large associational groups guided by beliefs that transcended the CCP (United Front Work Department of the CPC, 2006). This securitization process led to the introduction of long-term policies and practices to bring churches and clergy under control. As the next section demonstrates, the party-state's strategies to manage Christians are not only multi-dimensional, but also additive. They target different aspects of Christianity, such as patriotism among clergy and institutional oversight over churches, and work in tandem with one another to enhance the influence of the party-state over religious life.

Strategies of securitization

One of the first securitizing steps was to “liberate” Christianity from foreign influence. Foreign clergy and missionaries were expelled from the country, Christian schools and hospitals were nationalized or closed, and Christian leaders were expected to pledge their support to the new communist regime. Just as the Bolsheviks had cultivated “red priests” to align Orthodox Christianity with the goals of the Soviet Union (Roslof, Reference Roslof2002), the CCP required loyalty from priests and pastors. In return, Premier Zhou Enlai promised “Christianity complete freedom in Red China,” so long as imperialist tendencies were removed from churches and Christians supported the regime in building New China (FBIS, 1950a). The People's Daily justified these policies by casting Western missionaries as anti-Chinese agents whose “motives [were] often political rather than religious. Among them were spies and pioneers in aggression… [who] carried on activities against the interests of the Chinese people” (FBIS, 1950b). Chinese clergy were asked to sever all ties with the Vatican and foreign co-religionists, cultivate patriotism within their churches, and be vigilant about the threats posed by Western, anti-revolutionary conspiracies (Patterson, Reference Patterson1974; Goossaert and Palmer, Reference Goossaert and Palmer2011; Yang, Reference Yang2012; Wang, Reference Wang2020). For the new regime, all aspects of church life were expected to be free from foreign influence, but not necessarily from the influence of the party-state.

Religious patriotic associations

Another early strategy was to standardize party-state supervision over Christians. Chinese Catholics and Protestants were channeled into state-sponsored religious patriotic associations (RPAs) that were tasked with overseeing acceptable forms of religious behavior, limiting the autonomy of churches, and insulating them from external influence.Footnote 6 In practice, RPAs operated as communist-controlled mass organizations and were the “transmission belt” between the party-state and religious believers (Madsen, Reference Madsen, Kindopp and Hamrin2004, 93). Protestants were organized into the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM, 中国基督教三自爱国运动委员会) that centered around principles of self-governance, self-support, and self-propagation.Footnote 7 As the official Protestant church of China, the TSPM compelled Protestants to abandon denominational ties and cut off all communication and funding from abroad to “unite all Protestants in China under the leadership of the CCP and the People's Government.”Footnote 8 Not all Protestants welcomed these changes and rejected pressures to join the TSPM. Wang Daoming, an influential pastor, was a vocal critic of TSPM leadership, describing them as “followers of Judas” and “false prophets” (Wang, Reference Wang2002, 64–65). Wang and many of his supporters were arrested and imprisoned for refusing to join the state-led patriotic church (Zhao and Zhuang, Reference Zhao and Zhuang1997, 84).

Similarly, Catholics were channeled into the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association (CPA, 中国天主教爱国会); however, it proved more challenging to get bishops and priests to join. The CPA followed the same “three-self” principles as Protestants, which meant the Chinese Catholic Church was expected to be fully independent from Rome.Footnote 9 Pope Pius XII denounced these efforts and called on Chinese Catholics to resist the patriotic movement, making it extremely difficult to find clergy willing to risk excommunication (Madsen, Reference Madsen1998; Madsen, Reference Madsen, Kindopp and Hamrin2004, 94).

The establishment of RPAs and official patriotic churches meant little flexibility for Chinese Christians outside of these state-sponsored institutions as the only legal space for churches to operate was within the patriotic institutional framework. Christians who resisted or publicly criticized the RPAs were denounced as traitors and faced repression or imprisonment. He Chengxiang, the director of the Religious Affairs Bureau of the State Council, criticized clergy who refused to join as “unpatriotic” and labeled them as “political enemies” with “ulterior motives” seeking to “deceive some believers.” He called on “all good-hearted believers to see through this conspiracy and prevent themselves from being fooled by it” (He, Reference He1955, 4). The implication of these efforts was twofold: Christian communities were divided into either patriotic churches or those operating underground (Madsen, Reference Madsen1998; Yang, Reference Yang2012; Reny, Reference Reny2018); and those operating outside of official churches were labeled as traitors to the nation.

It should be noted that even within state-led patriotic churches the loyalty of Catholics and Protestants remained in question. Government representatives called on clergy to “infuse Marxist-Leninist Thought” into church doctrine and for “the positive values of patriotism” to replace “negative religious propaganda” (Patterson, Reference Patterson1974, 25). Some church leaders answered these calls by reimagining biblical stories through the lens of Marxism–Leninism, such as “stressing Jesus as a member of the working class (son of a carpenter) who recruited the proletarians (fisherman), denounced the greedy capitalists (money changers in the temple), and sided with the oppressed class (healing the leper)” (Chan, Reference Chan2019, 44–45). Others sought to find common ground by pledging the help of Christians to build an “independent, democratic, strong and modern China” (quoted in Wickeri, Reference Wickeri1988; Ng, Reference Ng2012, 209). In a highly securitized environment for Christians, signaling support for the party-state was necessary to preserve open religious expression; yet, this often was insufficient.

Chinese authorities took additional measures to cultivate patriotic priests and pastors and to remind the public of the ongoing threat of global Christianity. State-run media called on Christian circles to be vigilant against foreign threats and to promote political and ideological self-transformation because “imperialism, particularly U.S. imperialism, has not reconciled itself to death, but has continued to resort to all possible means in an attempt to use religion to perpetrate sabotage against New China” (FBIS, 1961). Subsequent government policies reinforced the need for patriotic clergy who “love their motherland” and “support the socialist path” (Document 19, section 5), and regime representatives stressed the need for politically reliable clergy who “love the country and religion” (Wickeri, Reference Wickeri1988; Ye, Reference Ye2002, 13; Wang and Zhao, Reference Wang and Zhao2017). To ensure patriotism took hold within churches, the party-state took a role in the training of religious leaders, thus reflecting the multi-dimensional and evolving approach to managing Christianity.

Securing seminaries

Developing a pipeline of patriotic and politically reliable clergy meant increasing the influence of the party-state within Chinese seminaries. This process began in the 1950s alongside the development of RPAs and has expanded over time. Entrance examinations for seminaries, for example, test prospective students' knowledge of socialist values and seminaries are directed to admit “young religious personnel, who, in terms of politics, fervently love their homeland and support the Party's leadership and the socialist system, and who possess sufficient religious knowledge” (Ma and Li, Reference Ma and Li2018, 100; Document 19, section 9). Here, the emphasis on fervent patriotism above knowledge or religious background underscores the ongoing suspicion of clergy and interests in cultivating politically reliable Christians.

The securing of seminaries also extends to their faculty. Current policies require all schools of religious training to employ instructors who “have good ideological and moral character” and are able to “educate students on the basic principles determined by the constitution, patriotism, unity, and progress among ethnic groups, the rule of law and national security” (Order No. 16, 2021b, article 45). Seminaries are expected to recruit faculty with sound political backgrounds, loyal to the CCP, again reflecting the highly securitized environment. For example, a February 2021 job posting from the National Seminary of the Catholic Church in China (中国天主教神哲学院) reveals the importance of politics. The seminary seeks English and Political Education instructors and the basic requirements underscore political loyalty. Candidates must have:

(1) Chinese nationality;

(2) A firm political stance, supporting the leadership of the CCP and the socialist system, firmly planting the “four consciousnesses,” strengthening the “four self-confidences,” resolutely achieving the “two safeguards” and closely aligning with the Party's Central Committee that has Comrade Xi Jinping at its core regarding ideology, politics, and actions;Footnote 10

(3) Supporting and obeying the constitution, laws, and regulations of the CCP.Footnote 11

It is also worth noting that the professional requirements for the positions—an MA in English Literature/Linguistics and MA Political Science/Marxist Philosophy—fall further down on the job posting, indicating the priority of political qualifications over professional ones.

The securitization of seminaries has also meant the integration of patriotic education into theological training (Order of SARA No. 16, article 39; also see Vala, Reference Vala, Ashiwa and Wank2009; Kuo, Reference Kuo2011). In addition to studying Church history and pastoral communication, seminarians are taught the “correct” understanding of church–state relations in political education courses, such as “Ideology and Politics” (思想政治课). Of course, the teaching of political and patriotic education in seminaries is not new, courses have been in place since 1955 (He, Reference He1955, 12). What is new, however, is that clergy must now devote at least 30 percent of their studies to patriotic education training (Order of SARA No. 16, article 39). These courses meet weekly and generally span multiple years of a student's theological education. Moreover, although patriotic education is present in all Chinese schools and is an extensive component of the national curriculum, the percentage mandated in seminaries is more than double of what is required in non-religious colleges and universities (Ministry of Education of the PRC, 2018).Footnote 12 This reflects not only the importance of the party-state places on the political orientation of future religious leaders, but also that religion remains securitized.

To ensure standardization of political education training across seminaries, course materials have been developed by the State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA). The Patriotism Textbook (爱国主义教程), used in both Catholic and Protestant seminaries, is organized around themes that emphasize how religion should serve the party-state, such as supporting the socialist system and leadership of the CCP, promoting ethnic and national unity, and protecting rule of law, national sovereignty and security (SARA, 2005, 5–9). The Patriotism Textbook also lays out an authoritative framework for understanding church–state relations through the lens of patriotism and love for the party-state. The textbook explains,

The view that “I love my country, but I do not necessarily love the CCP, and I do not necessarily love the government,” separates patriotism from supporting the leadership of the party and the government, or making them oppose each other, is incorrect. Religious [training] school students who sincerely love the country and religion must accept and support the leadership of the CCP, and cannot use freedom of religious belief and separation of church and state as excuses to get rid of the Party's leadership and the state's lawful management of religious affairs. (SARA, 2005, 368–369)

As this passage illustrates, the students are taught that the expected relationship between church and state is patriotism, and that patriotism is inseparable from the Party. Another important lesson—and one that is repeated throughout the pages—is that Christians must accept the Party's leadership in the management of religious affairs. Simply put: the Party leads and Christians must follow. A final lesson of the textbook is that patriotism and love of the Party is imperative in foreign religions, such as Catholicism and Protestantism. The Patriotism Textbook explains:

It is well known that the spread of Catholicism and Protestantism in China has been accompanied by the sufferings of the Chinese people…Against the backdrop of Western powers' aggression against China by using gunboats to open up China, foreign missionaries overall served as tools for imperialism and colonialism to invade China. Many foreign missionaries directly assisted the expansion of colonialism, engaging in opium trafficking, gathering intelligence, inciting and participating in military aggression, seizing economic benefits, participating in planning and coercing the Qing government to sign unequal treaties. (SARA, 2005, 300–301)

The passages above are revealing in two important ways. One is the detail in which they link Christianity to Chinese subjugation. This reflects the long-term securitizing frames used against Christianity—that is, Christianity remains a potential vehicle for foreign influence. The other is the underlying message that the modern Chinese church must be oriented around patriotism in order to move beyond Christianity's imperial and colonial past. Chinese Christians cannot follow foreign faiths, but must be loyal to the CCP, who will keep Christians safe.

In addition to the Patriotism Textbook developed by SARA, Catholic and Protestant seminaries use course materials designed for their specific communities in patriotic education courses. Catholic seminaries use the Chinese Catholic Independently and Autonomously-Run Church Course Material (中国天主教独立自主自办教会教育教材), a textbook published in 2002 by the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association (CPA) and Bishops Conference of Catholic Church in China (BCCCC). Protestants use the Protestant Patriotism Textbook (基督教爱国主义教程) developed in 2006 by the National Committee of the Three-Self Patriotic Movement of the Protestant Churches in China (TSPM) and the China Christian Council (CCC).Footnote 13 These textbooks are the most current editions available, serve as the authoritative course books in their respective seminaries, and the content reflects the political orientations the party-state deems as most important and wants to transmit to seminarians.Footnote 14 Although political knowledge is constructed in other ways, such as through teachers, families, friends, and the popular media, the textbooks provide a unique window into understanding how the party-state attempts to influence Catholics and Protestants. The textbooks not only convey the political values of those in power, but also reinforce the authority of the party-state over Christianity.

Data and methods

To unpack the content of patriotic education textbooks and how the party-state seeks to construct politically reliable priests and pastors, we combine qualitative and quantitative textual analysis.Footnote 15 This approach provides leverage in identifying the concrete political knowledge the party-state is attempting to transmit, as well as how the textbooks are seeking to orient seminarians favorably toward the party. To uncover patterns and associations that may be overlooked in the qualitative analysis, we utilize an Association Measure approach from corpus linguistics to examine how the textbooks associate certain ideas with the CCP and external threats.Footnote 16 Any two words “collocate” if they appear next to each other in a text. Association Measures detect collocations of words that have high degrees of cohesiveness and regularly appear together, as opposed to free word combinations that have low degrees of cohesiveness (Kolesnikova, Reference Kolesnikova2016). Association Measures also reveal relationships between words that a simple frequency count is unable to provide.

To evaluate the strength of word collocations, we utilize the log-Dice coefficient, an Association Measure that emphasizes the degree of exclusivity or mutual information between two words.Footnote 17 The log-Dice coefficient is a statistical validation measure operating on a scale with a fixed maximum of 14, with higher values indicating a more exclusive relationship between two words. Coefficients over 10 are considered highly associated (Rychlý, Reference Rychlý, Petr and Aleš2008). As a standardized measure, log-Dice permits comparison of the results between the textbooks. Log-Dice has the following expression where “f” stands for the frequency of a word, x or y, or of two words, x and y, appearing together (Rychlý, Reference Rychlý, Petr and Aleš2008):

Orienting Catholics and Protestants

How do textbooks orient seminarians toward the Party? The Catholic and Protestant textbooks follow a strikingly similar format to introduce church and party-state relations. Table 1 shows the parallel structure of the table of contents across the two volumes. Substantively, both begin with chapters on patriotism as part of the Christian tradition and stress that patriotism is the sacred duty of all Christians to love and serve the socialist motherland. The textbooks likewise situate external forms of Christianity within a historical context of imperialism, colonialism, and aggression against China. In doing so, this affirms the reorganization of Chinese Christians under the leadership of the party-state as well as the need to break external ties to protect Chinese churches from hostile, foreign forces and eliminate imperialist tendencies. The conclusions of both textbooks also provide parallel discussions of the merits of patriotic, progressive, and democratic churches built with Chinese characteristics and the ways in which Christians can contribute to a socialist society and serve the party-state.

Table 1. Chapter outline of patriotic education textbooks

As evident in Table 1, patriotism is a core theme across the textbooks and describes it as a sacred duty central to Christian teachings and traditions. The introductory chapters outline the nature of church–state relations in China as patriotic and patriotism is understood as both love of China and support for the Party. In chapter 3, for example, Protestant seminarians are asked to reflect: “How do you plan to inherit and carry forward the fine tradition of patriotism of Chinese Christians?” (TSPM and CCC, 2006, 185). Similarly, the Catholic textbook links patriotism to the Party in asking: “Why should patriotism be reflected first and foremost in supporting the leadership of the CCP?” (CPA and BCCCC, 2002, 22). Here, the expected answers are submission to and support for the CCP. The Catholic textbook teaches,

If you love the socialist motherland, you must consciously accept and support the leadership of the CCP. First, because China is taking the socialist road, it is inseparable from the leadership of the CCP. Second, because for over one hundred years in Chinese history, there has been no political party or social group able to take on the important task of leading the Chinese people to realize modernization compared to the CCP. (CPA and BCCCC, 2002, 12–13)

Catholics, therefore, learn that patriotism is inseparable with the CCP and that only the CCP can lead China. Protestants likewise are taught that “only the CCP can save China” (TSPM and CCC, 2006, 182); thus, reinforcing the lesson that Christians should follow the leadership of the CCP.

The Catholic and Protestant textbooks also provide guidance for how patriotic clergy should serve China. Chapter 10 of the Catholic textbook raises the question: “How to be clergyman who loves their country and loves [their] religion?” (CPA and BCCCC, 2002, 272). The given answer is that priests should manifest patriotism through anti-imperialist enthusiasm and make a clean break from the Church's imperial past (CPA and BCCCC, 2002, 263). The subtext, of course, is to associate the Vatican with imperial aggression against China.

Catholic clergy are also taught to fulfill their duty as citizens by putting China first—that is, “national interests and individual religious beliefs not only are not contradictory, but are closely related. Therefore, every clergyman and believer must hold high the banner of patriotism and put national interests first” (CPA and BCCCC, 2002, 265). Putting Chinese interests first means “loving the socialist motherland, advocating for the leadership of the CCP, persevering on the path of socialism, correctly handling the relationship between national interests and personal religious belief, and meanwhile, fulfilling the duty of being good citizens of the country and a good people of God” (CPA and BCCCC, 2002, 265). In sum, priests should link the Chinese Catholic Church to “the destiny of the motherland” and not to Rome (CPA and BCCCC, 2002, 266–267).

Another shared motif is the association of foreign Christians with aggression toward China, which justifies the severing of connections with Christian communities abroad. The Protestant textbook, for example, describes some Western missionaries as part of a “cultural invasion” (文化侵略) whose “activities were inseparable from imperialist political and cultural aggression” (TSPM and CCC, 2006, 128). Clergy learn that Western missionaries used schools, printing presses, and philanthropy as part of organized invasion efforts to manipulate Chinese public opinion and thinking (TSPM and CCC, 2006, 109–127). The Protestant textbook also warns of ongoing “overseas infiltration” so that clergy remain vigilant against hostile, external forces (TSPM and CCC, 2006, chapter 5).

The textbook also rallies Protestants to defend against ongoing foreign threats and repeats securitizing frames. The Protestant church should become a fortress protecting national sovereignty and clergy should protect the independence of the Chinese Protestant church as instinctually as “protecting their eyeballs” because the church has a responsibility to safeguard China's sovereignty (TSPM and CCC, 2006, 130). The Protestant textbook outlines long-term efforts of foreign forces to divide Chinese Christians, from ideology to organizational structure. It warns that if the infiltration of foreign forces are left unchecked, they will “undoubtedly pose a threat to national security, unity, and the quality of the population. Therefore, resisting the infiltration of foreign forces is an urgent task for China's churches, and it is also a sacred duty and fundamental quality that every theology student should possess” (TSPM and CCC, 2006, 258–259). Similarly, the Catholic textbook warns of a long-term threat, “imperialists used the church in various ways as the vanguard of their aggression…Their intention was to control the Chinese church, using it as an institution for long-term aggression and destruction in our country” (CPA and BCCCC, 2002, 106). “In order to break free from the conspiracy and aggression of imperialists,” theology students are advised to actively “work together to build a new China” (CPA and BCCCC, 2002, 106). These examples illustrate how seminarians are taught that their churches must be protected from hostile, foreign forces and the only way to do so is to actively support the leadership of the CCP.

Beyond these common themes, it is important to note where the Catholic and Protestant textbooks differ. One area of difference is in the naming of external threats. The Protestant textbook discusses foreign Christian threats with broad references to Western missionaries, whereas the Catholic textbook singles out the Vatican. Priests learn of the Vatican's close relationship with colonial powers that facilitated aggression against China, that the Vatican is responsible for co-opting Chinese Catholics leaders in the past, and the Vatican is indifferent to the resistance and will of the Chinese people (CPA and BCCCC, 2002, 81–92). The Vatican is further associated with harming the Chinese nation and the textbook taps into nationalist sentiment, such as discussing how “the Vatican sided with the Japanese invaders, attacked the CCP's proposition of a joint war of resistance, and tried to persuade the Chinese Catholics not to fight against Japan, but to oppose the Communist Party and the Communist Party's anti-Japanese proposition” (CPA and BCCCC, 2002, 87). Indeed, the Catholic textbook devotes an entire chapter to Vatican aggression during anti-Japanese and civil wars. The central message is that the Vatican openly supported the occupation of China: “The Holy See openly sided with the Japanese invaders, supported Japan's invasion of China, and opposed [anti-Japanese] resistance of Chinese believers” (CPA and BCCCC, 2002, 85). The Vatican is further condemned for supporting the Nationalist government and organizing anti-communist organizations to fight against China's liberation (CPA and BCCCC, 2002, 94). The lesson from the Catholic textbook is clear: the Vatican is an existential threat to China.

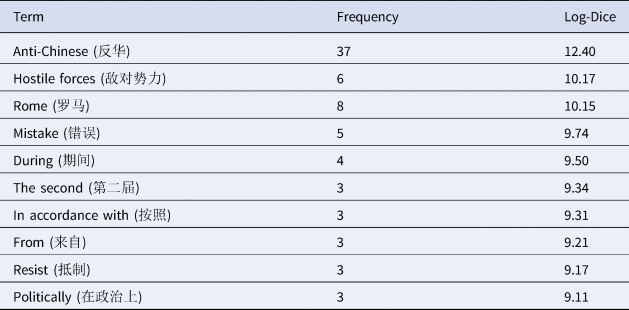

To put anti-Vatican sentiment further into context, we turn to the computational analysis and the terms most commonly associated with the “Vatican.” Table 2 presents the 10 terms most associated with the “Vatican” in the Catholic textbook. We find the most highly associated term is “anti-Chinese” (反华) and followed by “hostile forces” (敌对势力); the log-Dice coefficients of both confirm strong associations.

Table 2. Top collocates of “Vatican” in Catholic textbook

Note: Table shows statistical measures of collocation of top terms associated with “Vatican” (梵蒂冈) as identified using the log-Dice coefficient. The total frequency for the Vatican is 138; data reflect 2002 Catholic textbook.

To be sure, the association of the Vatican with negative terms is not surprising given the ecclesiastical authority of the Vatican over the universal Catholic Church, fear of foreign interference, and repeating subtext in the chapters that the Chinese Catholic Church is independent from Rome. However, the textbook does not directly denounce the Pope, but rather alludes to unnamed anti-Chinese and anti-communist forces within the Vatican. Seminarians are repeatedly reminded that the only path forward for Chinese Catholics is to remain politically independent and autonomous from the Vatican or risk being corrupted by anti-Chinese agents. They are instructed that “the Chinese Catholic Church will have a future in its evangelical cause only if it becomes politically independent and autonomous, perseveres in loving the country and the church, …[and] prevents the Vatican's anti-China forces” from taking hold (CPA and BCCCC, 2002, 145, emphasis added). The central lesson is that the anti-Chinese Vatican should have no political authority over Chinese Catholics and a clear boundary between church and state and between politics and religion must be maintained. Of course, this same rationale is not applied to the Chinese government because the Chinese Catholic Church should “want” to conform under the leadership of the CCP as patriotism demands.

Finally, we turn to computational analysis to further explore how the textbooks attempt to orient priests and pastors favorably toward the Party. Table 3 compares the 10 terms most associated with the “Chinese Communist Party” (CCP) in the two textbooks.

Table 3. Top collocates of “CCP” in the textbooks

Notes: Table shows statistical measures of collocation of the top terms associated with the “CCP” (中国共产党) as identified using the log-Dice coefficient. The frequency of the CCP is 70 in the Protestant textbook and 134 in the Catholic textbook. Data reflect 2006 Protestant textbook and 2002 Catholic textbook.

Here, we can make several observations. First, the terms associated with the CCP generally have positive connotations, such as leadership, endorse, support, founding, and cooperation. This is a sharp contrast to the negative terms associated with the Vatican and illustrate how positive and powerful language is attached to the Party. Second, the CCP is most highly associated with identical terms in both textbooks: “leadership” and “support.” Leadership collates with the CCP 61 times in the Catholic textbook and 23 times in the Protestant textbook. The log-Dice coefficients for these terms confirm the strong association. Moreover, the textbooks link the CCP to leadership and support in similar ways. The Catholic textbook instructs priests to “voluntarily accept and support the leadership of the CCP as the basic requirement for loving the country” (CPA and BCCCC, 2002, 12). The Protestant textbook teaches that theological education should nurture clergy who “politically support the leadership of the CCP, passionately love the socialist motherland and persevere in the direction of the Three-Self” (TSPM and CCC, 2006, 2). For Catholics and Protestants, the textbooks dictate there is neither a contradiction in nor an alternative to supporting the CCP.

The analysis thus far has examined the highly securitized environment for Christians and unpacked the policies and practices used to extend the reach of the party-state into the micro-foundations of religious training. These strategies of control have severed links with foreign coreligionists, channeled Catholics and Protestants into state-led patriotic churches, and promoted patriotic education in seminaries to reinforce the authority of the CCP over Christian affairs. These policies work in tandem with one another to increase party-state oversight over Christian affairs. The focus now shifts to recent securitizing moves under Xi Jinping that further expand party-state influence.

Securitizing religion under Xi Jinping

The securitized environment for religion has hardened under Xi Jinping. While previous Chinese leaders also placed a high premium on the threat of religion and sought to ensure it serves the interests of the party-state, Xi has taken a number of steps to bring religion under greater control by labeling it as an essential component of China's holistic national security (Xi, Reference Xi2014; Laliberte, Reference Laliberte2015, 204; Xinhua, 2021c).Footnote 18 This securitizing move has had several implications. Bureaucracies that oversee religious groups have been streamlined and restructured to increase CCP supervision and oversight; religious regulations have been strengthened and expanded; and all religious communities have been called on to “Sinicize” (中国化) and embrace Chinese traditional culture and values (Xinhua, 2022, 2016; Xu, Reference Xu2022). For Catholics and Protestants, these new measures of control build on past efforts, but expand the reach of the party-state deep into Christian communities in new ways, including shaping religious doctrines and activities and calling for the merger of party loyalty, patriotism, and Chinese culture.

Institutional oversight

A highly securitized environment for religion under Xi has meant the restructuring of institutions to expand party-state control over Christians. In 2018, the SARA—the government agency tasked with overseeing religious affairs since the 1950s—was reorganized under the United Front Work Department (UFWD) to “strengthen the Party's centralized and unified leadership over religious work” (Xinhua, 2018). This administrative shift is significant because the UFWD reports directly to the Central Committee of the Party. Meaning, the management of SARA has shifted from the government to the Party, which removes the arms' length oversight of religion to a full embrace by the most powerful organs of the CCP (Xinhua, 2021a). For Catholics and Protestants, the institutional shift means their patriotic associations now directly report to the UFWD, which is tasked with guiding clergy and believers to “adapt to a socialist society,” educate them in “socialist core values,” and prevent “foreign forces from interfering with and dominating” Chinese churches (Xinhua, 2021a). Interestingly enough, the UFWD is the same organization that Mao praised as a “magic weapon” of the Party to defeat domestic and foreign enemies, thus sending a strong signal as to how Xi intends to govern Christian communities (Chang, Reference Chang2018, 37).

Regulations

Xi has further expanded oversight over Christians with new regulations and revisions to earlier policies, such as the Regulations on Religious Affairs (RRA, 2018), Measures on the Administration of Internet Religious Information Services (Order No. 17, 2022), and Measures on the Management of Religious Clergy (Order No. 15, 2021a). These regulatory changes remind believers and clergy to remain “compatible with socialist society,” “put core socialist values into practice,” “resist the infiltration of foreign forces,” “love the motherland,” “support the leadership of the CCP,” and “safeguard national interests”—all themes present in earlier policies and patriotic education training (RRA, 2018, articles 3–5, 64, and 73; Order No. 15, 2021a, articles 3, 6, and 12). However, the regulations are distinctive in several ways. One is that they openly elevate religion to the level of national security. The regulations explicitly prohibit large, religious gatherings that endanger national security, public safety, or disrupt social order (RRA, 2018, article 64). The likely rationale of these changes is to contain the public gathering of Christians, which has been an area of contention for some unregistered churches (Reny, Reference Reny2018). Another distinction is that the regulations directly link religion to extremism and terrorism, especially regarding ties to overseas groups. The Measures on the Management of Religious Clergy warn clergy that any support of religious extremism, terrorism, sowing ethnic divisions, or accepting employment from foreign religious organizations are threats to national security (Order No. 15, 2021a, article 12). Similarly, the RRA cautions religious bodies and believers against propagating extremism or engaging in terrorist activities under the guise of religion (RRA, 2018, articles 4, 45, 63, and 73). These policies, however, fail to define religious extremism and terrorism, leaving the door open for uneven implementation.

The regulations additionally increase oversight over the dissemination of religious materials, including printed and online content. While past policies also placed restrictions on the printing and distribution of religious literature, both the RRA and Measures on the Administration of Internet Religious Information Services expand party-state supervision to online spaces. The given rationale is to protect “national ideological security” and safeguard “the legitimate rights and interests of religious citizens practicing core socialist values” (Order No. 17, 2022). One could argue that the unstated motivation is to reign in religious activity online, which has been a key arena for evangelizing, especially among younger populations and for connecting with Christians outside of China (Wielander, Reference Wielander2013; Maslakova, Reference Maslakova2019, 439). Churches and seminaries are now required to secure a license to operate online and all content from religious images and sermons to microblogs and live streaming of services must be approved by regime representatives and comply with existing laws (RRA, 2018, articles 47, 48, 68; Order No. 17, 2022, article 6). More importantly, online religious content must “not instigate the subversion of state power, oppose the leadership of the CCP, [or] undermine the socialist system, national unity, and social stability” (Order No. 17, 2022, article 14).

These new steps to securitize religion under Xi are important not only because they reveal expanding oversight of the party-state over Christian communities in person and virtually, but also because they signal a legalistic turn. The regulations make clear that Christian bodies and believers who endanger national security and cause social unrest will be held accountable in accordance with the law. In this way, securitization resembles efforts in other autocracies to reign in religious life, as in Russia where anti-extremist legislation has been used to target religious minorities, such as Jehovah's Witnesses (Koesel and Dunajeva, Reference Koesel, Dunajeva, Philpott and Shah2018). China is now poised to do the same.

Sinicization

A final securitizing strategy under Xi Jinping has been to Sinicize religious communities to embrace Chinese traditional culture and values. For Catholics and Protestants, this builds on past efforts to promote patriotism and loyalty within TSPM churches and to develop a Chinese Christian theology that is compatible with Chinese socialism (China Daily, 2014; Xinhua, 2021b; Li, Reference Li2022). However, securing Christianity through Sinicization also expands the influence of the party-state over new aspects of religious life, including doctrine.

Xi first introduced Sinicization in 2015, suggesting that the Party must guide religion to “adhere to the direction of Sinicization” (Jiao, Reference Jiao2015; Madsen, Reference Madsen and Madsen2021, 1). Since then, Sinicization has been promoted at the highest levels of government. At a 2016 National Conference on Religious Work, Xi called on religious communities to “dig deep into doctrines and canons that are in line with social harmony and progress, and favorable for the building of a healthy and civilized society, and interpret religious doctrines in a way that is conducive to modern China's progress and in line with our excellent traditional culture” (Cui, Reference Cui2016; Xinhua, 2016). At the 2022 Party National Congress, Xi repeated the Party's steadfast commitment to guide religion and that Sinicization of religion is necessary for religious groups to adapt to China's socialist society (also Xinhua, 2017, 2022, 34). All of this suggests that the Party is wading directly into “culture work.”

To ensure that Sinicization takes hold, Xi has joined provincial leaders on high-profile visits to religious sites to promote Sinicization's benefits of “harmony and stability” and to help religious communities “resist infiltration and destruction” from outside influences (Tian, Reference Tian2019; Hebei Daily, 2021; Li, Reference Li2021; Su, Reference Su2021). Xi has also called for the development of the “Three Troops” (三支队伍) to advance Sinicization efforts at home and protect China from hostile religious forces from abroad (CCTV, 2021; Xu, Reference Xu2022). The Three Troops initiative brings together Party and government officials, prominent religious representatives, and academic researchers of religion to ensure the coordinated development of Sinicization (Ma, Reference Ma2022; Xu, Reference Xu2022). Indeed, there is growing evidence that the Three Troops efforts are underway in both Catholic and Protestant communities (Lan, Reference Lan2022; Zhao, Reference Zhao2022). At the 10th National Congress of Chinese Catholics, for example, over 350 priests and laypeople from 28 provinces joined with scholars and representatives from the UFWD to address deepening the “theological construction of Sinicization” in Chinese Catholicism (Lan, Reference Lan2022).

Of course, Sinicization is hardly new. Xi's predecessors from Mao to Hu all took steps to adapt Marxism–Leninism to a Chinese context, which led to the development of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics and Sinicized Marxism (Hu, Reference Hu2007; Cheng, Reference Cheng2018; Su, Reference Su2021; Wang, Reference Wang2021; Yang, Reference Yang and Madsen2021). Historically, Christian missionaries also attempted to root churches locally to make them more acceptable (Xu, Reference Xu, Kindopp and Hamrin2004). Matteo Ricci, for example, dressed in gray robes like a Buddhist monk, presented himself as a Confucian scholar, and introduced Catholicism through Confucian concepts (Ricci et al., Reference Ricci, Lancashire, Hu and Malatesta1985, 6, 9, 13; Liu, Reference Liu2014). All of these efforts sought to Sinicize Christianity so that it would take hold and flourish in China. However, the CCP's Sinicization of Christians is distinctive from earlier efforts in that it actively situates the Party and politics at the center of religion.

Yang Fenggang argues that the ongoing Sinicization campaign “is not about cultural assimilation and integration, but political domestication of Chinese Christians” and suggests that “Chinafication” better captures the political objectives of the party-state (Yang, Reference Yang and Madsen2021, 38, 16). We agree with Yang's assessment that Sinicization is not primarily focused on embracing Chinese traditional culture or indigenizing Christianity, but advance the argument further to suggest Sinicization is about ensuring fealty to the party-state. Although calls for Sinicization invoke traditional China culture and values, in practice Sinicization prioritizes the integration of Party ideology, Party leadership, and Party loyalty. Sinicization is the “party-ification” (党化) of Christianity.Footnote 19 It increases both Party control and Party presence in churches.

Sinicization as party-ification is evident in a reference guide for government officials. The guide describes Sinicization in the following way:

Adhering to the direction of Sinicization of our country's religion means that religious personnel and believers must identify and agree with politics, love the motherland, support the socialist system, support the leadership of the CCP, and abide by the laws, regulations, and policies of the country; integrate culturally, meaning to interpret religious teachings according to the requirement of contemporary China's development and process and in line with the excellent traditional Chinese culture; adapt to society; adjust religious concepts, systems, organizations, etc. (Zhong, Reference Zhong2019, 62)

What is revealing from this passage is the importance of politics over traditional culture and of the Party over religion. Although Xi's Sinicization efforts call on Christians to become “more Chinese,” in effect, this means conforming to the current political ideology of the party-state “without expressing any doubts about its realism or consistency” (Madsen, Reference Madsen2019, 13). With Sinicization, the Party is folding culture and cultural work under its purview with the understanding that traditional Chinese culture and values are defined by the political interests of the regime.

Sinicization channeled by official churches

Interestingly, the numerous calls to Sinicize religion have not yielded a central policy outlining how churches should do so. Rather, religious communities have taken the lead in Sinicization efforts. The Catholic and Protestant patriotic associations have issued five-year plans outlining the development of Sinicization in their churches (CCC and TSPM, 2018; CPA and BCCCC, 2018). These Sinicization plans largely follow the broad strokes promulgated by the party-state—that is, Sinicization prioritizes the inclusion of politics over culture and acceptance of CCP leadership. The Catholic plan explains that “adherence to the direction of Sinicization of Catholics in China requires conscientious approval of politics. Love of the motherland, and obedience to the national regime is the responsibility and obligation of every Christian.” For Catholics, “the core of political approval is to accept the leadership of the CCP, support the socialist system, and preserve the authority of the Constitution and laws, the unity of the people, and the integrity of the motherland.” Sinicization is necessary to build a “harmonious foundation” of relations between Catholicism and the party-state and the integration of core socialist values to “enrich the practice of Sinicization of Catholicism” (CPA and BCCCC, 2018, II).

The Protestant plan is equally political and calls for the harmonization of Biblical teachings with the ideology of the party-state and for pastors to preach core socialist values from the pulpit. Core socialist values should be integrated into seminaries and promoted in “classrooms, teaching materials and students’ minds” and become a “standard for rating the development of civilized and harmonious churches” (CCC and TSPM, 2018, I). In short, the plan recommends churches be evaluated on their successful integration of Party ideology.

Beyond political ideology, both Catholic and Protestant plans give some attention to rooting religious rituals in Chinese culture. The Protestant plan recommends displaying expressions of faith in forms such as traditional melody, calligraphy, and paper cutting (CCC and TSPM, 2018, IV). Pastors should blend notions of love and respect attributed to Mencius with Biblical teaching that focus on loving others as yourself (CCC and TSPM, 2018, V). Catholics should look to Chinese philosophy to enrich Church theology as well as embrace elements of traditional culture into liturgy, spirituality, sacred music, architecture, and interior designs of church buildings while avoiding “radical or blind reform of rites, and resisting reluctance to change” (CPA and BCCCC, 2018, V, VII). The Catholic plan, therefore, is careful to note that Sinicization efforts should be seen as voluntary and flexible without, in fact, endorsing any deviation from the party-ification of churches.

To carry out Sinicization efforts, Catholics outline a plan to organize a team of architects and artists and develop a “Chinese Catholic Music and Art Training Center” to compile hymns with characteristics of Chinese Catholicism (CPA and BCCCC, 2018, VIII). When training priests on Catholic rites, the seminaries will also introduce education on traditional Chinese etiquette and history (CPA and BCCCC, 2018, VII). Protestants will similarly adjust seminary curricula to increase the proportion of courses on “the core socialist values, patriotism, Chinese history, literature, philosophy and arts and other traditional culture” (CCC and TSPM, 2018, III). Evidence indicates that Sinicization of seminaries is well underway. In 2020, faculty from 20 Protestant seminaries attended a conference to discuss revisions to the Protestant Patriotism Textbook, the main political education textbook (Lin, Reference Lin2020). Among the speakers were faculty from the School of Marxism and representatives from the Ideological and Political Teaching Committee at the Ministry of Education (Lin, Reference Lin2020), suggesting the political direction the revisions will take.

Sinicization as “public transcript”

It is also important to consider how scholars and local churches have responded to Xi's calls to Sinicize and the five-year plans. These efforts largely mirror the CCP's narrative on Sinicization as integrating political ideology and support for the CCP into churches and can be understood as reflecting the “public transcript” on Sinicization of Christianity (Scott, Reference Scott1990, 45; Vala, Reference Vala2018). The idea here is that the party-state controls, if not dominates, the “public stage” of Christian development in China and Catholics and Protestants learned to speak the language of the party-state or the official transcript (Scott, Reference Scott1990, 4, 18, 50; also see Kotkin, Reference Kotkin1995). The official transcript represents not only what the party-state wants to hear, but also what is expected of Christians in public spaces. It mirrors the discourse of the regime and is accommodationist. Of course, there is often a disconnection between the performed public transcript and what may be occurring in spaces where the party-state is less visible (Scott, Reference Scott1990, 4; Vala, Reference Vala2018); however, we suggest that Christian communities are contributing to the official Sinicization transcript in important ways.

Scholars of Christianity are helping ground Sinicization historically by highlighting the indigenous roots of Chinese churches and long history of embracing Chinese characteristics (Wang, Reference Wang1996; Zhang, Reference Zhang2001; Yang, Reference Yang and Madsen2021). Some date Sinicization to the indigenization movement led by Christians in the 1920s that transformed expressions of faith to be more Chinese in character, such as designing weddings and funerals similar to traditional Chinese rites (Wang, Reference Wang1996) and adopting the style of Buddhist prayers in churches (Zhang, Reference Zhang2001). Chinese theologians have also contributed to Sinicization debates by advocating for the integration of classical Chinese philosophy into Christianity, such as Confucian ideas of “benevolence” (仁) and “moderation” (中庸) (Xiao, Reference Xiao2001; Yan, Reference Yan2011). For these scholars, Sinicization is described as a natural progression and even “willed by God” because it fuels evangelization and church growth (Wang, Reference Wang1996; Chen, Reference Chen2018; also see Lee and O'Brien, Reference Lee and O'Brien2021, 907). These efforts reflect how Christian communities are helping write the public transcript on Sinicization.

Catholic and Protestant churches have likewise found innovative ways to perform publicly Sinicization. Some Protestant churches in Beijing have begun regularly holding flag-raising ceremonies and organizing congregants to hand-make the national flag (Communist Party Member Web, 2109). Others have hosted activities such as “patriotic book corners” (爱国书角), patriotic speech contests, and photo exhibitions (Communist Party Member Web, 2019). Still others have organized competitions among pastors to deliver the best sermon on the Sinicization, with examples including “A Brief Discussion on the Core Values of Socialism Based on Christian Beliefs of Honesty” and “Value System–Patriotism” (Xixing Subdistrict Office, 2022). Some churches have celebrated Sinicization efforts with lectures instructing how to meditate on the common ground of Chinese philosophy, core socialist values, and the Bible (CCC and TSPM of Guangdong Province, 2022).

Some Catholic churches have participated in Sinicization by arranging pilgrimages to “holy sites” for the CCP. The Yibin Catholic Diocese in Sichuan organized a “Red Journey of Thanksgiving to the Party” that visited the museum commemorating the Red Army's crossing of the Chishui river and camps operated by the Nationalist government that imprisoned martyrs of the revolution (Jing, Reference Jing2021; Sichuan Catholic Web, 2021). These “red” pilgrimages have been described by church leaders as an effort to “stay true to their original mission of patriotism,” understand the “sacrifice of the revolutionary martyrs,” and “walk with the Party and government in the same direction” (Jing, Reference Jing2021; Sichuan Catholic Web, 2021).

Other churches take more creative approaches to Sinicization. The Fujian Protestant Theological Seminary hosted a celebration for the 100th anniversary of the CCP and invited high ranking party-representatives from bureaucracies that oversee religion (CCC and TSPM of Fujian Province, 2021a). The celebration featured a musical, “With No Regrets,” that depicts sentimental stories of Christians who have devoted their life to serving the Party (CCC and TSPM of Fujian Province, 2021b). One Christian figure featured is Chen Guoxiang, a preacher imprisoned by the Nationalist government for hiding communist guerrillas. Another highlights Patriotic Pastor Wu, a covert soldier for the Red Army. The musical also tells the story of a Fujianese Christian, known as the “red doctor” (红色医生), who was baptized as a child, embraced the Chinese revolution, and “dedicated his entire life to the Party, country, and People's Army's medical needs” (CCC and TSPM of Fujian Province, 2021b). The principal message from the musical is that faithfulness to God and faithfulness to the Party go hand-in-hand; being a good Protestant means to support the Party.

These examples are more illustrative than exhaustive, but they show the diverse ways in which Christians are complying publicly and participating in writing the public transcript on Sinicization. They also reinforce the point that Sinicization in practice is the party-ification of Christianity. Of course, these Sinicization efforts are for public consumption and the intended audience is likely the party-state. Our data do not provide insight into whether Christians are participating in these efforts voluntarily or begrudgingly, what is happening behind closed doors when the party-state is less present, or whether Sinicization efforts are more than a survival strategy for Christian communities. However, research by Lee and O'Brien (Reference Lee and O'Brien2021) offer some important insights on these points. Based on extensive interviews with Protestants, Lee and O'Brien conclude it is difficult to determine whether Protestants are embracing Sinicization as “grudging compliance,” “acceptance of the inevitable,” or “active consent” (Reference Lee and O'Brien2021, 913). At the same time, they argue that Protestants are far from passive and are actively “maneuvering inside the box they are confined in, helping shape the space within which Protestantism operates, and exerting meaningful influence over what the Xi effect amounts to on the ground” (Lee and O'Brien, Reference Lee and O'Brien2021, 904, 913). Our analysis complements these findings and suggests that Christians are not only “maneuvering inside the box” of Sinicization but are to a degree deciding the shape of the box itself. So far, the party-state seems content to allow churches some flexibility to Sinicize, so long as their efforts align with the official transcript and show necessary reverence for the Party. This observation also resonates with broader studies of church–state dynamics in China. This research demonstrates that although the party-state maintains considerable power over religious groups, Christian communities are not without leverage in their interactions with local authorities (Huang, Reference Huang2014; Koesel, Reference Koesel2014; Liu and White, Reference Liu and White2019) and can be given a wide berth in their activities, especially when they signal support in patriotic ways (Huang and Yang, Reference Huang, Fenggang, Yang and Tamney2005; McCarthy, Reference McCarthy2013).

Conclusion

This article set out to examine the shifting strategies of the party-state to regulate Christian churches in contemporary China. We demonstrated that securitization of Christianity is an ongoing process that has meant the expansion of the party-state deep into religious life, from severing ties with foreign Christians and organizing patriotic churches to cultivating patriotic pastors and priests and attempting to influence the micro-foundations of religious training. Our analysis of patriotic education in seminaries detailed how clergy are educated to favor the party-state, disdain foreign Christianity, and understand Chinese church–state relations through a patriotic lens. Throughout the article we have also shown that patriotism is being constructed not only as love for China, but also as love for the CCP.

Under Xi Jinping, we demonstrated that the securitization of religion has expanded with new efforts to increase party-state control over Christianity, including bureaucratic restructuring and regulations to increase oversight over various aspects of religious life. Most notably has been the calls for Christians to become more “Chinese” in orientation and to Sinicize. We find that Sinicization efforts focus less on the inclusion of traditional Chinese culture or values, in favor of the political orientation of churches. Sinicization integrates socialist core values and love for the leadership of the CCP at the center of religious life. The practical effect is that Sinicization is wholly party-ification of Christianity. More research is needed, however, to explore the implications of Sinicization, whether these efforts will displace other values within churches or what coexistence will look like over time, and what is taking place outside of the official transcript on Sinicization.

These findings also contribute to a growing body of work on the strategies authoritarian leaders use to entrench their power and manage societal groups (see, especially, Wintrobe, Reference Wintrobe2001; Gandhi and Przeworski, Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2006; Svolik, Reference Svolik2012; Frantz and Kendall-Taylor, Reference Frantz and Kendall-Taylor2014). We demonstrate that the management of religion moves beyond strategies of overt violence and toward multifaceted efforts to transform religion so that it aligns with the ambitions and interests of those in power. These long-term and multi-dimensional strategies of control offer new insight into how authoritarian leaders attempt to “domesticate” religion and religious communities in order to minimize perceived threats.

The findings also contribute to a deeper understanding of how Christians negotiate highly restrictive environments where religion is viewed as a security threat and the state is strong. We offer new empirical evidence into how Catholics and Protestants signal they are patriotic and the innovative ways they contribute to writing the official transcript on Sinicization. In spite of these innovations, however, we remain pessimistic that Sinicization will translate into greater religious freedom or political capital for Chinese Christians. Catholics and Protestants are minorities in China, and the party-state has given no indication of downgrading the threat of religion. In fact, Xi's inclusion of religion as part of China's holistic national security suggests the opposite. Religion will continue to operate in a highly securitized environment.

A final contribution is providing insight to the securitization of religion within China. This is important for two reasons. One is that it traces the evolving reach of the party-state into churches. Although Chinese authorities uphold the Marxist perspective that the death of religion is an inevitable historical process, they are nevertheless developing new strategies to shape the doctrines and practices of Christianity that put the Party at the core. Indeed, these strategies of control are not limited to Catholics and Protestants, but are applied to all religious groups. This would suggest that the Chinese government is planning for a long-term coexistence with religion and expecting growing religious communities to share the political values of the Party. Thus, the party-ification of religion will likely expand. The other reason is that it brings China into comparison with other countries that have elevated religion to an issue of national security. China is following the lead of countries such as Russia in taking on the role of both defender and definer of religion. China is securitizing spiritual and moral values to preempt perceived domestic threats and to counter external influence. Considering that religious beliefs and practices are growing in China, including among communist party members who are expected to remain atheists,Footnote 20 there is every reason to expect the securitization of religion will continue.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048323000329.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the editors of Politics and Religion and the external reviewers for their valuable feedback. We are also grateful to Kevin O'Brien, Loren Reinoso, Susan McCarthy, Eddy U, David Stroup, Juan Wang and the participants of the Identities and Nation-state Building in China Workshop for comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors, Peitong Jing and Karrie J. Koesel, declare none.

Peitong Jing is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame.

Karrie J. Koesel is an associate professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame.