Fifty of their most important outposts and nine hundred and eighty-five of their most famous villages were razed to the ground. Five hundred and eighty thousand men were slain in the various raids and battles, and the number of those that perished by famine, disease and fire was past finding out. Thus nearly the whole of Judaea was made desolate.

(Cass. Dio, Rom. Hist. 69.14.1–2Footnote 1)Scholars have long been skeptical of the historical accuracy of Cassius Dio's account of the consequences of the Bar Kokhba War (132–36 CE).Footnote 2 Several issues underlie their skepticism: the meaning Dio assigns to the toponym Judaea, the scope of the revolt and of the ensuing destruction of towns and villages, and the estimates of the number of settled sites in the region and its population during the period in question.Footnote 3 And yet, Cassius Dio is accepted as the most reliable historical source for the Second Revolt and this passage includes the only demographic figures in the literary sources concerning the population of Judaea in the Roman period. Reassessing Dio's accuracy thus has broader implications for the history of the Second Jewish Revolt and the demography of Roman Judaea, as well as our understanding of Dio's other descriptions and Roman record-keeping in wartime.

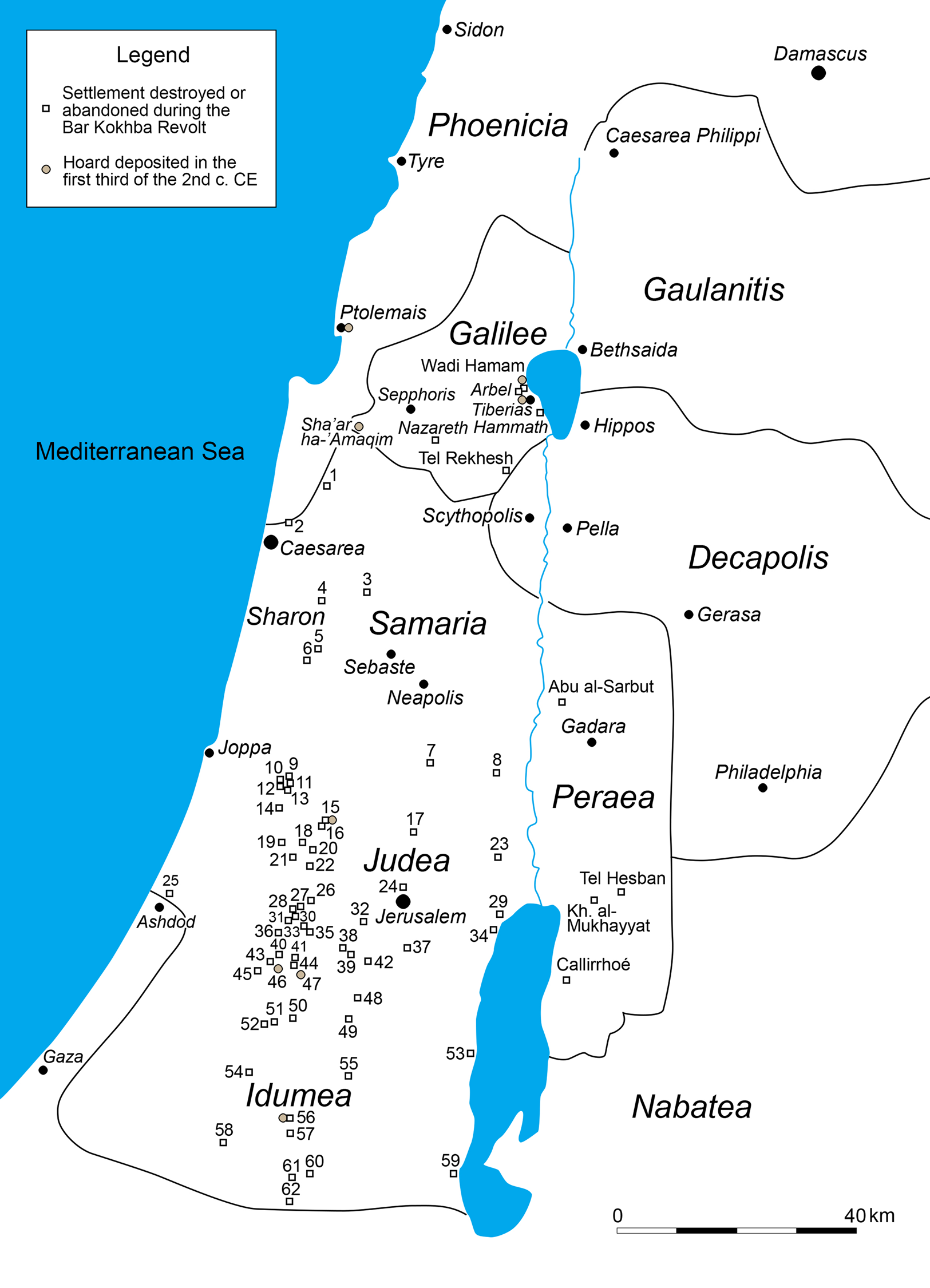

Precisely what Cassius Dio meant by “Judaea” may be a decisive factor for assessing the veracity of his account. The two main possibilities are the entire area of the Roman Provincia Judaea (province of Judea)Footnote 4 or the more limited geographic region denoted by the term “Land (or Country) of Judea” (Fig. 1).Footnote 5 If Dio was referring to the entire Roman province, his account places the revolt in most of the districts of Palestine, which contradicts what we know from other sources. On the other hand, if he had in mind the Land of Judea, it is hard to make his demographic data compatible with that limited region.

Fig. 1. Map of regions of Jewish settlement in Provincia Judaea from the late Second Temple period through the Bar Kokhba War. (Map by D. Raviv.)

Given that most texts from the Roman Period use “Judaea” to refer to the entire province, we may assume that Cassius Dio, too, wrote about the province and not just the Land of Judea.Footnote 6 Here we should note his use of the term to mean the region between Phoenicia and Egypt (Rom. Hist. 37.16). Recently, B. Isaac has proposed that Dio used “Judah-Judaea” with an ethnic sense, to mean the region of Jewish settlement within Provincia Judaea – that is, the “three lands.”Footnote 7 This would explain why he employed “Judaea” instead of “Palaestina” which was the current name of Provincia Judaea in his time. A similar ethnic reference is found in Pliny the Elder, who includes the 10 toparchies, Transjordan, and the Galilee in the region he calls “Judaea,” while excluding Samaria, Idumea, and the coastal cities (HN 5.70).

In accordance with Isaac's proposal, which we accept, Cassius Dio's count of the settlements destroyed in the war includes villages (κῶμαι) and forts (φρούρια) in the Land of Judea, Peraea (Jewish Transjordan), and other districts where the archaeological record indicates that the residents took an active part in the revolt. His reference to the destruction of the “important villages” (ὀνομαστόταται κῶμαι) might mean that his account omitted some sites destroyed during the war (such as manor houses and estates).Footnote 8 In the absence of clear criteria for determining what he considered to be an “important” village or a fort (see below regarding the settlement hierarchy), it is impossible to assess the reliability of his account as a whole.

To date, assessments of Cassius Dio's demographic data have relied on the results of the relatively superficial archaeological surveys conducted in and around Judea in the last three decades of the 20th c. In this article we reassess Dio's account, drawing on new archaeological evidence from excavations and more intensive surveys conducted in recent years in Judea, Peraea, and the Galilee. After reconstructing the scale of the revolt, we reconsider Dio's demographic data by applying the following research methods: an ethno-archaeological comparison with the settlement picture in the Ottoman period; a comparison with a similar settlement study conducted for the Galilee; and an estimate of settled sites from the Middle Roman period (70–136 CE), focusing on the Land of Judea and especially the northern Judean hills.Footnote 9 In light of the many methodological problems associated with estimating the population of ancient Palestine, we will concentrate on trying to determine the number of settlements destroyed in the war.Footnote 10 Following a short summary of the previous research on this topic, we define the region whose residents participated in the revolt and then present the results of the current study.

Research history

Reviewing the research history and the methods used by previous scholars shows the need for a broad and up-to-date archaeological database and a productive, multi-pronged methodology. S. Applebaum was the first to try assessing Cassius Dio's demographic data in the light of findings in the field. Drawing on the results of the “Emergency Survey,”Footnote 11 he estimated the agricultural capacity of Judea, Samaria, and the Jordan Valley.Footnote 12 His calculations included a number of variables (and unknowns), including the total number of Roman-period sites that had been uncovered or could be expected to be found in future surveys and in other regions; an estimate of the rural population in the upland regions of Byzantine-era Palestine; and demographic figures for modern Arab villages. This yielded a population of 552,427 persons for Judea and Samaria during the Roman period. Applebaum concluded that Cassius Dio's numbers were plausible and that in any event it should be assumed that the revolt extended beyond Judea to include Samaria and part of the Lower Galilee, and that it also affected Transjordan and Idumea.

M. Mor disputed Applebaum's estimate, on two main grounds. First, Mor pointed out that we cannot be sure that every survey site dated to the Roman period had a Jewish settlement at the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, or that it was one that took an active part in the revolt and was destroyed by its end. Second, he noted that Applebaum's estimates were lower than Cassius Dio's figure of wartime fatalities, which, according to Mor, included only soldiers and not civilians. According to Mor, Dio's data do not reflect the historical reality; nor is it possible to draw conclusions from them about the extent of the revolt outside the boundaries of Judea proper.Footnote 13 In his opinion, we should doubt the reliability of Dio's account, given its “apologetic tone” and the fact that it was edited at a later date. He asserts that Cassius Dio's “exaggerated” description was prompted by the need to justify the Roman legions’ heavy losses while suppressing the revolt.Footnote 14 Mor stresses that the absence of data and the lack of certainty regarding the size of the Jewish settlements make it difficult to give credence to Dio's figures.

In contrast, W. Eck, who focused on the Roman side, noted that Cassius Dio's description accords with the realia reflected in inscriptions and other sources about the Roman military forces.Footnote 15 In his view, the origin and number of military units that were called into service to suppress the revolt, the involvement of the governors of the neighboring provinces (Arabia and Syria), and various actions that the Roman authorities implemented at the end of the rebellion clearly indicate that during the revolt the Imperial forces faced an extraordinary emergency throughout Provincia Judaea.

A. Kloner noted Applebaum's incomplete data and unknowns, including sites in what Kloner termed “Samaria,” a region where no hiding complexes have been found and which he does not believe was involved in the revolt.Footnote 16 He noted that initial surveys documented finds from the late Second Temple period at more than 400 sites in the Judean foothills. In his estimation, there were more than a thousand settlements in Judea (without “Samaria”) at the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, with a population of between 700,000 and 900,000.

B. Zissu documented more than 320 settled sites in Judea where the archaeological finds clearly indicate a Jewish population from the late Second Temple period through the Bar Kokhba Revolt.Footnote 17 Along with Kloner and H. Eshel, he noted that the distribution of the finds associated with the Bar Kokhba Revolt indicates active participation by the residents of the entire Land of Judea.Footnote 18 They concluded that Cassius Dio's demographic data reflect the settlement picture in Judea on the eve of the Bar Kokhba Revolt.

From this review, two main points emerge that demonstrate the need for a reexamination of the subject. First, the archaeological data referred to by previous scholars was very partial and did not allow for a clear definition of Jewish settlement areas from the days of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Second, any such assessment should be based on a precise definition of the area to which Dio referred. To this is added, of course, the central role of the archaeological evidence in reconstructing the Second Revolt, due to the lack of detailed and reliable historical sources.

The extent of the region that took part in the revolt

Bar Kokhba coins, destruction layers and abandonment deposits, hiding complexes, and refuge caves dated to the Bar Kokhba Revolt are indications of active participation in the uprising and help us demarcate the region in which it took place.Footnote 19 The coins are especially important because they coincide with the territory controlled by the Bar Kokhba administration. In addition, evidence from the mid-2nd c. CE onwards for the presence of a non-Jewish population in areas that were previously Jewish indicates that the Jews there were victims of the suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt.

Judea

Even though we understand Cassius Dio's use of “Judaea” to mean “Greater Judea” – i.e., all the districts of Jewish settlement in Provincia Judaea (primarily the “Three Lands” of Judea, Transjordan, and the Galilee) – the undeveloped state of research in Transjordan requires that our discussion focus on finds in the Land of Judea and the adjacent regions (the coastal plain, the Sharon, southern and western Samaria, Idumea, and the northern Negev), which, according to the archaeological record, were home to Jews who participated in the Bar Kokhba Revolt and which were consequently devastated by the rebellion's end.

Finds in the categories listed above have been uncovered throughout Judea proper and in adjacent regions, including the coastal plain, Idumea, the Samarian foothills, and the Sharon.Footnote 20 It should be emphasized that these regions are all part of the Land of Judea as that term was used from the late Second Temple period until the Bar Kokhba Revolt. During the Middle Roman period, this territory was divided into at least 10 toparchies – Gophna, Thamna, Acrabatta, Jericho, Herodium, Zif, Pella/Bethleptepha (Beit Nattif), Emmaus, Lydda, and Joppa – and several cities, such as Caesarea, Antipatris, and Jamnia. Except for the coastal plain and the cities with a mixed population, during the Early and Middle Roman periods Jews predominated in the vast majority of the rural areas under discussion here.Footnote 21

Among the finds mentioned above, the hiding complexes merit special attention. Although the phenomenon dates back to the late Second Temple period, the archaeological finds indicate that most of them were hewn out and used during the Bar Kokhba Revolt, in accordance with Cassius Dio's account. The hiding complexes in the Galilee are exceptions to this dating; only 20 can be associated with the Second Revolt.Footnote 22 The dating of most of the hiding complexes to the Bar Kokhba Revolt, the magnitude of the phenomenon (more than 460 systems have been documented in roughly 250 sites in Judea, in addition to 75 systems at about 50 sites in the Galilee), and their geographic distribution make the hiding complexes the most important evidence for estimating the boundaries of the region whose residents took an active part in the Bar Kokhba Revolt (or at least the region that made preparations for it). It should be emphasized that the distribution of the finds strongly reflects the involvement in the uprising of the residents of the northern Judean hills and western Samaria;Footnote 23 these regions were previously considered outside the territory involved in the revolt.Footnote 24 It will also be noted that these were regions of Jewish settlement, in contrast to the Samaritan population of central Samaria, which does not appear to have taken part in the revolt, and in any event was not significantly harmed by it.Footnote 25

The most salient and significant remains for delineating the region that participated in the war and was left depopulated and in ruins by its end are destruction layers and abandonment deposits (including hoards). Another type of evidence is provided by finds that reflect population exchanges and the penetration of non-Jewish residents into previously Jewish districts. Remains of this sort are generally discovered only through archaeological excavations. The excavations conducted in the Land of Judea point to the almost total destruction of Jewish settlement there at the end of the Bar Kokhba War.Footnote 26 Furthermore, it should be emphasized that evidence of destruction or abandonment dated to the Second Revolt has been discovered in most of the excavated Roman-period settlements in the wider region of Judea (Fig. 2 and Table 1). What is more, above these layers there is a gap in settlement.Footnote 27 Destruction layers and abandonment deposits have been found both in buildings and in underground installations carved out either underneath or near settlements, such as hiding complexes, burial caves, storage facilities, and field towers. The finds from Judea are supplemented by fragmentary evidence from Transjordan and the Galilee.

Fig. 2. Map of excavated sites in Provincia Judaea where destruction layers or abandonment deposits from the time of the Bar Kokhba War have been found. (Map by D. Raviv.)

Table 1. Names of the sites in Figure 2. References for each of these sites and additional bibliography are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Peraea (Jewish Transjordan)

The Jewish settlements in the Peraea, documented in historical accounts and archaeological finds from the late Second Temple period, no longer existed in the Late Roman and Byzantine periods. Their disappearance may be connected with the First Jewish Revolt (66–73 CE) or with the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Josephus's description of the Peraea Jews’ participation in the First Jewish Revolt suggests that there was little fighting there and that they were less involved than their brethren in the Galilee and Judea, districts where Jewish settlement continued after the First Jewish Revolt. Given that only a few of their settlements actively participated in the First Jewish Revolt, scholars have concluded that it is unlikely that it put an end to Jewish settlement in Peraea.Footnote 28 Moreover, Talmudic texts refer to Jewish residents there during the Jamnia generation (the period between the revolts),Footnote 29 and an inscription from 131 CE found in the Judean desert mentions a bridegroom named Joshua ben Menahem of the village of Soffathe in the Livias district in Peraea.Footnote 30

Finds that may reflect the Peraea Jews’ participation in the Bar Kokhba Revolt or their victimization at that time are a destruction layer from the first third of the 2nd c. CE at Tel Abu al-Sarbut in the Sukkoth Valley, and 2nd-c. CE abandonment deposits at al-Mukhayyat and Callirrhoe.Footnote 31 To these are added finds associated with a Roman military presence in the Peraea in the mid-2nd c. CE which indicate that the Jews there were victims of the suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. One of these is a papyrus, signed in Caesarea in 151 CE, which includes the name of a Roman veteran from the village of Meason in Peraea.Footnote 32 The implication of this document is that land in Peraea had been expropriated and granted to Roman settlers. Other evidence of the Roman military presence is a building inscription of the Sixth Legion dated to the 2nd c. CE found at a-Salt, which is to be identified as Gadara, one of the main Jewish settlements in Peraea.Footnote 33 The Peraea Jews’ participation in the Bar Kokhba Revolt may also be adduced from the remains of an impressive Roman fortification system in the Jordan Valley, uncovered during the Manasseh Hill Country Survey.Footnote 34 This system, which includes the remains of a military encampment and three fortresses, is dated to the 2nd c. CE and specifically to the period of the Bar Kokhba Revolt.Footnote 35 Ben David has proposed that the location of these fortifications, facing northern Peraea between the Sukkoth Valley and Regev, indicates that their chief targets were the Jewish settlements in Peraea.Footnote 36

Galilee

There is evidence that some Galilee residents participated in or at least prepared for the war: 19 hiding complexes dated to the 2nd c. CE; a destruction layer and two hoards discovered in Khirbet Wadi Ḥamam; a destruction layer in the southern synagogue of Ḥammath Tiberias, which has been dated to the end of the first third of the 2nd c. CE; finds indicating abandonment in the first half of the 2nd c. CE uncovered at Tel Rekhesh, Arbel, and Nazareth; hoards from the first third of the 2nd c. CE unearthed at three additional sites in the Galilee; remains from the period between the two revolts found in excavations of the Roman fortifications at Mt. Nitai; finds from the 2nd and 3rd c. CE in three karst caves in eastern Upper Galilee; and coins of Trajan found in the Nahal Amud cliffs.Footnote 37 Nonetheless, Jewish settlement in the Galilee as a whole was not affected during and after the Bar Kokhba Revolt. In his survey of the eastern Lower Galilee, U. Leibner reported that no settlement that had been studied was wholly abandoned then. What is more, it was in the period from 136 to 250 CE that settlement in the area peaked.Footnote 38 This archaeological evidence fits well with what we know from rabbinic texts about the flourishing of houses of study in the Galilee and the development of the Mishnah, the Tosefta, and the Halakhic Midrashim during the 2nd and 3rd c. CE – after the Bar Kokhba Revolt.

An ethno-archaeological comparison with the Ottoman period

A basic datum that can be used to estimate the scale of ancient settlement sites in Judea is the number of Arab villages in the region during the Ottoman period, for which there is relatively abundant demographic data.Footnote 39 This comparison will help evaluate the carrying capacity of the territory of Judea by giving an idea of whether this area ever had such a high number of settlements.

There were about 800 Arab villages in the Land of Judea during the Ottoman period, a number not very different from Cassius Dio's figure.Footnote 40 Note that surveys conducted in Judea tend to indicate that settlement in the Roman period was denser than in the Ottoman period.Footnote 41 If so, the figure of 800 villages for the Ottoman period should be taken as a minimum estimate of the number of settlements in that region in the Roman period.

A comparison with similar research on settlements in the Galilee

C. Ben David has conducted a similar demographic study of Jewish settlement in the Galilee during the late Second Temple period. Because of its importance for the current study, we will briefly review his methodology and results.Footnote 42 Ben David evaluated Josephus's report that there were 204 Jewish settlements in the Galilee in the Early Roman period (Vit. 235). On the assumption that Josephus's count included the Jewish district of the Golan (currently the central Golan Heights), he included the latter in his calculations. Ben David drew on two main bits of information: the number of Arab villages in the Galilee and the Golan in the 19th c.; and the number of Early Roman period settlement sites documented in high-resolution archaeological surveys of the central Golan and the eastern Lower Galilee. With regard to the first of these, the 185 villages identified in the region in the 19th c. indicate its potential; the figure is very close to Josephus's 204 settlements. As for the second item, the surveys located 68 Early Roman period settlement sites in the two regions. The total area of these surveys, 500 km2, covers about a third of the total area of the Galilee (roughly 1,500 km2). Extrapolating from the survey and multiplying its settlement count by three also yields 204 settlements in the Galilee. Assuming there was no significant difference between the Galilee and Judea with regard to the density of settlement, we can use the figure for the Galilee to estimate the number of settlements in Judea.Footnote 43 The area of the Land of Judea, excluding the arid desert, is about 6,500 km2, or four times as large as the Jewish Galilee. From this ratio, we can further extrapolate from the Galilee findings to arrive at an estimate of 800 villages in Judea during the Early Roman period – again, not significantly different from Cassius Dio's figure.

An estimate of the number of Middle Roman period settlements in the Land of Judea on the basis of the archaeological evidence

The results of archaeological surveys and excavations conducted in recent years, especially the excavations at rural sites all over the Land of Judea and its environs, supplemented by the New Southern Samaria Survey, enable us to assess Cassius Dio's demographic picture in greater detail than was previously possible.Footnote 44 The archaeological surveys provide the most important data for estimating the number of settlements at the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt.

The area of Jewish settlement in the Land of Judea is estimated at 6,500–7,000 km2, compared to 1,500 km2 in both Peraea and the Galilee. As mentioned above, the settled area of the Land of Judea was computed from the archaeological record, which indicates a continuous belt of Jewish settlement from the late Second Temple period through the Bar Kokhba Revolt, running from the Carmel in the north to the Negev in the south, but excluding central and northern Samaria, parts of which were inhabited by Samaritans.

Results of the archaeological surveys

Our evaluation of the data from the surveys conducted in the Land of Judea had to take into account several methodological problems. These included the lack of a systematic distinction between settlement sites and other contemporaneous sites with minimal remains (such as scattered sherds, agricultural installations, and tombs); the failure to specify the size and number of sherds collected at each site; the absence of a breakdown of Roman-period sites into secondary periods (Early, Middle, and Late Roman); the limits on excavating within villages that are inhabited today; and the fact that some regions still have not been surveyed, and surveys for others have not yet been published. In light of the incomplete data, we cannot currently offer a precise estimate of the number and size of settlements from the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt in Judea. What we can do is take the total number of Roman-period sites as the potential number of settlements for the period in question and use the data from the published high-resolution surveys to extrapolate the potential for Judea as a whole.

The surveys conducted in the Land of Judea count a minimum of 1,049 Roman period settlement sites.Footnote 45 It should be emphasized that this number includes only settlement sites and not all the sites surveyed. Note further that this is not the figure for all Roman-period settlements in the entire area, because the results of some surveys remain unpublished. If we rely on the maps produced by the unpublished surveys, the total number of sites jumps to between 1,345 and 1,465.

Although it is problematic to use this figure of Roman-period sites documented in surveys, given their lack of classification into secondary periods, the high-resolution data from published surveys do not reflect an increase in the number of settlements at the transition from the Early Roman to the Late Roman period. It can therefore be assumed that the vast majority of Roman-period sites were settled during the Early Roman period. In any event, when we try to start from the Roman-period sites to calculate a number for Bar Kokhba settlement sites, we must take into account the devastation in the region as a result of the First Jewish Revolt, as well as the growth of settlement activity in various parts of Judea in the Late Roman period.

The excavations and surveys conducted in Judea point to substantial settlement continuity from the Early Roman to the Middle Roman period. The available data do not permit a good estimate of the number of settlements destroyed during the First Revolt that were not resettled during the ensuing decades. Nevertheless, it appears that the destruction during the First Jewish Revolt was centered in Jerusalem and its rural hinterland.Footnote 46

A comparison between the settlement potential indicated by these calculations and Cassius Dio's account must also consider the population of the various localities, because the standard interpretation of his text is that his number for the destroyed settlements includes only important or well-known villages and not every locality. This means that we must subtract manor houses and perhaps also some of the small villages, according to Safrai's proposed classification, from the total number of settlement sites.Footnote 47 The authors of the surveys estimated that, in those years, between a third and half of all the settled sites in Judea were manor houses and small villages. Working from this proportion, we arrive at between 900 and 1,000 sites that can be considered important villages, or about two-thirds of the total number of settled sites.Footnote 48

On the other hand, we need to add the number of important/well-known sites that were destroyed in other parts of Provincia Judaea, mainly in Peraea and the Galilee. In his study of Jewish Transjordan, based on the Jordanian Antiquities Department's database, Nahum Sagiv documented about 160 settlement sites in Peraea where Late Hellenistic and/or Early Roman pottery items were identified.Footnote 49 Based on a comparison with the size of Jewish Galilee and the results of the Galilee survey, which indicated that Josephus's figure of 204 settlements was realistic (as Ben David showed), 160 settlements in Peraea is a realistic estimate. Although hiding complexes, refuge caves, and Bar Kokhba coins have not been discovered in Transjordan, the few excavations conducted there indicate a continuity of Jewish settlement after the First Jewish Revolt, followed by abandonment or destruction during the Bar Kokhba Revolt and a settlement gap during the Late Roman period.

The northern Judean hills (southern Samaria) as a test case

Because the surveys published to date do not provide sufficient information for determining the number of Middle Roman period settlement sites throughout Judea, we offer instead the results of a recent study in the northern Judean hills that clearly defined which settlement sites could be assigned to this period. This region, which runs from the Bethel highlands to the valleys around Nablus, was within the boundaries of Judea from the late Second Temple period until the Bar Kokhba Revolt.Footnote 50 Our study draws mainly on a reexamination of the data of the New Southern Samaria Survey and the Ephraim Survey, supplemented by the finds from archaeological excavations, other surveys, and fieldwork.

Finds from the surveys and excavations conducted in the northern Judean hills were assigned to the Middle Roman period on the basis of parallels to assemblages that could be precisely dated to the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Despite the morphological similarity in assemblages of pottery and glass items from the Early and Middle Roman periods, there are several features distinctive of the latter period, and especially the years of the Bar Kokhba Revolt itself, including the types of storage jars, jugs, kraters, casseroles, cooking pots, and oil lamps.Footnote 51

The results of the Ephraim Survey enable us to identify 62 settlement sites from the Middle Roman period in the region between the Bethel highlands and the Nablus area.Footnote 52 To these can be added 17 excavation sites where Middle Roman period artifacts have been unearthed and 8 sites where previous surveys and fieldwork uncovered remains from this period. The New Southern Samaria Survey documented sherds from the Middle Roman period at another 44 sites. Thus, we have a total of 131 settlement sites in the northern Judean hills where sherds that can be precisely dated to the Middle Roman period have been found. There are also at least four Jewish settlements that are mentioned both in the sources reflecting the situation during the Jamnia generation and in scrolls from the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, but where no finds from the period in question have been uncovered.

To sum up, we have clear archaeological and historical data for 135 Middle Roman period settlement sites in the northern Judean hills. Of these, 123 sites are clearly in the northern districts of Judea. We can plausibly add the 94 Arab villages currently inhabited in this area (on top of the 30 villages already included) that are located at ancient settlement sites. The cores of these villages have excellent natural conditions (nearby springs, agricultural areas, and ancient roads) and would have been among the largest and most important settlements in the region in antiquity. If we assume that half of these village sites remained inhabited at the transition from the Early to the Middle Roman period, as was the case with other sites in the region (a decrease of about 50% in the number of inhabited localities), we can add another 47 settled sites, producing a total of 170. It should be emphasized that this is the minimum number of settlements for this region during the Bar Kokhba Revolt, because it is likely that even more modern village sites were inhabited at this time. If so, we reach an estimate of 170 to 220 settlements in the northern Judean hills. As mentioned, the total area of the Land of Judea during this period was 6,500–7,000 km2, while that of the northern Judean hills is 1,150 km2, or about a sixth of the Land of Judea. Assuming that settlement density elsewhere in Judea was similar to that in the northern Judean hills,Footnote 53 there would have been more than a thousand settled sites (170–220 × 6 = 1,020–1,320) in the Land of Judea alone. To corroborate this estimate we need to reexamine the results of surveys conducted in other parts of Judea.

Another way to estimate the number of settlements in the northern Judean hills at the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt is to compare the situation during the Ottoman period. In that period, settlement in the same region peaked at about 150 villages in the 16th c.Footnote 54 This figure is based on the 124 villages that appear on the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF) map of the region, plus 26 villages found on the taxpayer rolls from the end of the 16th c.Footnote 55 The archaeological surveys yield 188 Ottoman-period settled sites in the northern Judean hills, compared to 118 Middle Roman sites in the same region. Of the Ottoman-period settlements, 108 are inhabited today and 80 are abandoned; of the Bar Kokhba settlements, 16 are currently inhabited and 102 are in ruins. That is, there are more ruins from the Middle Roman period (102) than from the Ottoman period (80). If we assume that the abandoned ruins reflect the zenith of settlement in the region, the available data indicate that settlement in this region at the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt exceeded that in the early Ottoman period. Accordingly, the number of villages in the northern Judean hills during the early Ottoman period, 150, can be taken as a minimum for the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. This number is somewhat smaller than the figure produced by the previous calculation (170).

Surveys in the northern Judean hills also attest to the destruction of Jewish settlements at the end of the war. According to the survey data, there were 49 settlements in the Late Roman period, compared to 131 in the Middle Roman period. Of the 49 Late Roman sites, 38 were already inhabited during the Middle Roman period; in other words, 93 of the 131 Middle Roman period sites (71%) were abandoned.

Discussion

In light of the increasing pace of archaeological research on rural Palestine in the Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine periods, we may assume that the picture sketched in this article will be more firmly established as time goes on. Nonetheless, the findings of this study permit a better assessment of the accuracy of Cassius Dio's account of the results of the Bar Kokhba War than was previously possible. Dio's account has three main sections: “All of Judea” (Ἰουδαία πᾶσα) prepares (ἐκɛκίνητο) for the revolt; “almost all” (ὀλίγου δɛῖν) of Judea is destroyed; and, finally, Dio provides numerical data about the devastation. The information at our disposal supports the thesis that Cassius Dio used the term “Judaea” to mean all the areas of Jewish settlement in Provincia Judaea (Fig. 1). Although his statement that the entire province prepared for the revolt contradicts what we know from the Galilee, it is possible that ἐκɛκίνητο (whose basic sense is “to be disturbed” or “to prepare for rebellion”) conveys the idea that Jews in the different parts of the province were not passive, but it does not denote active preparation and participation by all the Jews living there. It is logical that, given the familial, social, and political connections linking the residents of Judea, the Galilee, and Peraea, there was significant movement within Palestine during the revolt. This movement presumably included people, equipment, supplies, families reuniting, and other activities associated with preparing for and waging the war.

Cassius Dio's reference to the destruction of “almost all of Judea” can be explained by what we know about the total annihilation of Jewish settlement in the Land of Judea and its surroundings, as well as the incomplete evidence from Peraea that may indicate that its Jewish residents took part in the revolt and suffered as a result. In light of the findings from the Galilee, which show clearly that most of its residents did not take an active part in the war and escaped unharmed, it is possible that Dio's “almost” means that Jewish settlements in two of the Three Lands of Provincia Judaea were destroyed. We should emphasize that the Land of Judea was much larger than the regions of Jewish settlement in the Galilee and Peraea (more than twice the size of the other two regions combined), and that there were additional areas of settlement adjacent to the Land of Judea, including the Sharon and western Samaria, forming a belt of nearly continuous Jewish settlement from the Land of Judea northward to the Galilee, from the late Second Temple period until the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. This belt of Jewish settlement ran as far as Mt. Carmel, which is commonly accepted as marking the boundary between Provincia Judaea and Provincia Syria (Phoenicia).Footnote 56

As for how many settlements existed in the Land of Judea at the time of the Bar Kokhba War, the archaeological evidence, primarily from excavations, indicates that not every Second Temple period settlement should automatically be included in the count for the years between the two revolts and during the Bar Kokhba Revolt. The current study has suggested that three independent methods yield the result that there were more than a thousand settlements in the Land of Judea during the Bar Kokhba Revolt: (1) the number of Ottoman-period villages (about 800) and the lower density of settlement then than during the Roman period; (2) the total number of Roman-period settlement sites in the region in question, according to the archaeological surveys (1,345–1,465), a number that reflects the settlement potential; and (3) the number of settled sites from the Middle Roman period that have been documented in the northern Judean hills (170–220), from which we computed the number of settlements in the rest of the Land of Judea, assuming similar density, and reached a result of more than a thousand; to this must be added settlements in the Peraea and the Galilee that were destroyed during the war. These settlements located in Judea, Peraea, and Galilee may be among Cassius Dio's 985 destroyed villages.

The sites documented in the Land of Judea include dozens of fortified settlements from the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, which may be among Cassius Dio's 50 destroyed fortresses. As mentioned previously, in the absence of Dio's definition of a fortress, it is impossible to confirm this number. S. Yeivin remarked the closeness of the Midrashic reference to 52 or 54 battles (pulmesa'ot) that Hadrian waged (Lamentations Rabbah 2:4) and Dio's 50 fortresses.Footnote 57 A number of scholars have attempted to identify these fortresses in the field.Footnote 58 It is worth noting that it is difficult to identify and classify fortified sites from the period in question, because most of them were settled in later periods and the old fortifications were reused (some are still inhabited today). This imposes significant limitations on the study of settlement remains because of the sites’ state of preservation and because of the problem of accessing them. To this can be added the small number of archaeological excavations of relevant sites, because a scientific dig is sometimes the only way to identify and date Roman-period fortifications. Another obstacle to the identification of destroyed rebel fortresses is that the historical background is often unclear and it is impossible to determine whether fortifications were manned by Jewish or Roman forces.

Archaeologists have found five types of sites that might be included in Cassius Dio's category of outposts (φρούρια): (1) fortified towns or villages located on ancient tells;Footnote 59 (2) fortified towns or villages that had been royal (Hasmonean-Herodian) fortresses or strongholds; (3) towns or villages that were fortified during the First Jewish Revolt or for defense against bandits;Footnote 60 (4) fortified sites that had previously been manned by Roman soldiers, such as the outposts along the Roman limes; and (5) fortified manor houses and estates. Dozens of these sites have been documented in the Land of Judea, in Peraea, and in the Galilee.

Regarding the number of casualties suffered by the residents of Judea in the war, given the great uncertainty about the size of settlements and the population density, we must make do with a general estimate that reflects the potential indicated by the archaeological record. Working from the total settled area in the Middle Roman period that was documented in southern Samaria, we can offer a rough estimate of 500,000–650,000 for the population of the Land of Judea. To this we must add the Jewish residents of Transjordan and the Galilee who were killed during the war. Given the scale of popular resistance and the absence of a clear distinction between military forces and civilians on the Jewish side, it seems reasonable that Dio's figure of 580,000 represents the total number of Jewish victims of the war (“the slain of Beitar”), both soldiers and noncombatants. This explanation is also consistent with the accepted view that such demographic numbers should usually be understood as the total numbers of the population.Footnote 61 Hence, Mor's claim about Cassius Dio's exaggeration would be acceptable only if Dio were referring here to military forces alone.

We can supplement the archaeological record with literary sources that report the results of the war on the Jewish side, as discussed at length in the scholarship.Footnote 62 The most noteworthy of these are rabbinic texts that offer wildly exaggerated figures for the slaughter in Judea, in contrast with the continued Jewish settlement in the Galilee.Footnote 63 Despite the legendary character of some of these accounts, their juxtaposition with the settlement picture offered here allows us to propose that these sources refer to Judea in the narrow geographic sense (the Land of Judea) and that the “slain of Beitar” denotes all the Jewish casualties of the war.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the potential contribution of the archaeological record and supports the view of those scholars who have taken Cassius Dio's demographic data as a reliable account, which he based on contemporary documentation.Footnote 64 Population numbers presented in literary sources are commonly believed to be unreliable. However, the present article suggests that in some cases, especially when the numbers are not “suspiciously neat,” their reliability can be relatively high.Footnote 65 The source of Dio's figures may be a record made by Roman officials during the war or afterward, either as part of Roman military record-keeping culture or within the framework of a census conducted by the Roman administration in this time of demographic change.Footnote 66 The present study thus illustrates the important contribution of a productive, multi-pronged methodology of archaeological study for the evaluation of literary descriptions of demographic data originating from Roman military record-keeping in wartime.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1 provides references for each of the sites mapped in Fig. 2, with additional bibliography. To view the supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047759421000271.