Introduction

The prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is growing with the aging population, especially in China, one of the biggest developing countries which now has a demographic situation where the growth of the aged population has outpaced that of the younger generation,Reference Li, Shen and Chen1,Reference Jia, Wang and Wei2 in what can be termed “the grey society.” Therefore, defining the mortality and risk factors for mortality of those with AD will help us to understand the burden of the disease and provide beneficial changes in directing patient care. However, except for some reports about the prevalence of AD in China,Reference Jia, Wang and Wei2 there are little standardized mortality ratio (SMR) data with long-term follow-up in AD patients within China in the past two decades, when there has been substantially better health care available compared to two decades prior. Therefore, the present study was modeled after previous studiesReference Wang, Cheng and Zhang3 where in AD patient the mortality and associated risk factors were investigated in a clinic-based cohort.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This study is of a clinic-based cohort and follows a rigorous approach to answer the critical questions of survival and causes of death in AD. All AD patients belonging to the Chinese household registration system were recruited from the memory clinics of Rui Jin Hospital and Hua Shan Hospital by December 31, 2007 during the prior 365 days. These two hospitals accept AD patients referred from general practitioners, community doctors, and emergency department doctors all over the country. The memory clinics of Rui Jin Hospital affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine and of Hua Shan Hospital affiliated with Fudan University, Shanghai, are the two biggest referral centers for AD diagnosis and follow-up in Shanghai, and in the entire country. Initial inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of AD in accordance with the NINCDS-ADRDA for AD.Reference McKhann, Drachman and Folstein4 Patients with mild cognitive impairment were excluded. Due to an absence of accurate information from death certificates of other provinces, patients who lived outside of the Shanghai metropolis were excluded from the present study. All participants were assessed at baseline and followed up in the clinic or community until December 31, 2017.

The study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Rui Jin Hospital affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China. Written informed consent was obtained from legal guardians of each participant.

Clinical Assessment

At baseline, researchers collected subjects’ general information face to face, including demographic information, living conditions, and detailed medical history. Comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), and hyperlipidemia, were noted in particular. Then, all the subjects received a detailed neurological examination and underwent a psychiatric interview. The patients had a clinical diagnosis of probable dementia of Alzheimer type according to NINCDS-ADRDA.Reference McKhann, Drachman and Folstein4 Age at onset of AD was recorded as the age when the first symptoms were perceived by the patient or family member(s). The timing of symptom onset was based primarily on the reports of clinical symptoms from the subject and/or from family members, including when they first noticed that something was amiss. Participants underwent annual follow-up, but neurocognitive tests taken at baseline were not repeated during follow-up due to their heath conditions. All data gathered were verified by senior specialists.

Ascertainment of Vital Status

As of December 31, 2017, we confirmed the vital status of all participants. For those who had died, death certificates (cause and date of death) were obtained from the database of the Shanghai Municipal Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China, which also confirmed the veracity of the information therein. Estimates of mortality based on the municipal registry provided more precise information than phone calls to family members. Diagnoses on the death certificate were registered using the International Classification of Disease tenth revision (ICD-10). Primary causes of death were grouped into different categories based on the ICD-10 classifications.

Statistical Analysis

An expected number of deaths were obtained by applying the age- and sex-specific mortality rates of the Chinese urban population in the period 2008–2017, based on the China Public Health Statistical Yearbook (2008–2017). A Kaplan–Meier survival curve was used to assess the cumulative survival rate of AD patients. The t-test or χ 2 test was used to calculate differences between the survival group and deceased groups. Potential risk factors for death were entered into Cox’s proportional hazard modeling according to the results from the t-test or χ 2 test and previous reports.

All above data analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software. All p-values were two-tailed, and we considered p < 0.05 as significant.

Results

Sample Characteristics

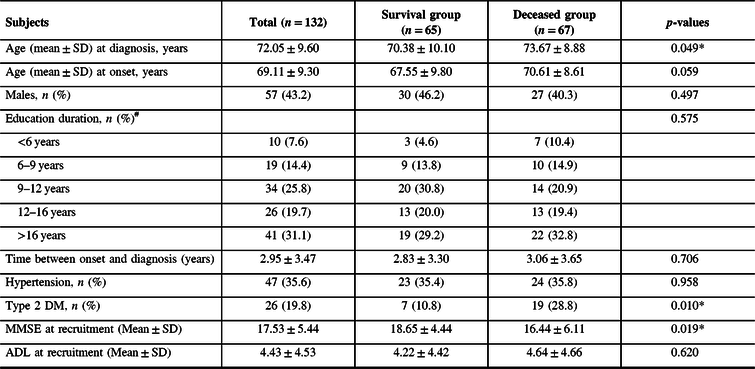

A total of 132 AD patients were followed up in the clinic until December 31, 2017. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics for survival and death in patients with AD

#The education information of two persons is missing.

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; ADL = Activity of Daily Living Scale.

*p < 0.05.

Mortality and Factors Related to Death

SMR of AD patients and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) is 1.225 (95% CI 0.944–1.563), comparable with an age- and sex-matched Chinese urban population over the same period. Mean survival time of AD patients from time of symptom onset is 145 (95% CI 126–164) months. Additionally, a Kaplan–Meier plot illustrates that type 2 DM at AD presentation predicted poor survival (p = 0.01) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Survival curves using the Kaplan–Meier method. Kaplan–Meier plots illustrating the overall survival, the effect of gender, and clinical phenotype at AD symptom onset and dependence on these traits of survival. (A) The survival curve of the total sample; (B) the effect of gender; and (C) concomitant type 2 DM effect on survival of AD patients in the cohort. Survival period begins at perceived symptom onset.

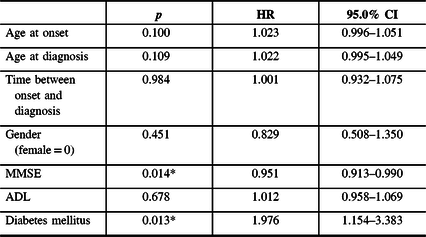

Findings of the single-factor Cox regression analysis are shown in Table 2, and the concomitant type 2 DM and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score were factors involved in statistically significant differences between the survival group and the deceased group (p < 0.05).

Table 2: Prediction of survival in AD in single-factor Cox’s proportional hazards regression model (HRs and 95% CI)

Abbreviations: MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; ADL = Activity of Daily Living Scale; HR = hazard radio; CI = confidence interval. *p < 0.05.

The independent predictors of mortality during follow-up were MMSE score (hazard ratio (HR) = 0.950, 95% CI 0.912–0.991 p = 0.016) and concomitant type 2 DM (HR = 1.845 95% CI 1.064–3.198, p = 0.029) after adjusting for age and sex, Table 3).

Table 3: Findings of the multivariate Cox regression analysis with time-dependent covariates for age and sex

Abbreviations: MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; HR = hazard radio; CI = confidence interval.

*p < 0.05.

Discussion

In the present study, we identified a similar mortality rate (1.225, 95% CI 0.944–1.563) for patients with AD compared to the general population over a 10-year follow-up period and also found that lower MMSE score and comorbid DM are predictors for poor survival. Although some previous studies indicated differential mortality of patients with dementia compared to the general population,Reference Li, Shen and Chen1,Reference Cereda, Pedrolli and Zagami5 our present study supports a nominally normal survival outcome despite an AD diagnosis during prior decade in Shanghai.

Several reasons can potentially explain why our current study demonstrates no elevated mortality for AD patients compared to various prior studies. (1) First, the diagnostic criteria used and rigorous clinical diagnosis in the present study exclude other types of dementia, such as frontotemporal dementia and vascular dementia. Indeed, according to a previous population-based study,Reference Garciaptacek, Farahmand and Religa6 non-AD dementias are associated with shorter survival and a higher risk of death than associated with AD. (2) Second, patients in this study were urban residents, a majority having a high level of education, and such persons tend to be sensitive to memory decline and to seek medical attention actively. Recently, a study by Zhou et al.Reference Zhou, Wang and Zeng7 also found that age-standardized years of life lost were significantly lower than the national mean for major causes including AD in Shanghai. Meanwhile, participants in our study are mostly from urban Shanghai. It is reasonable that patients from the urban, coastal region in eastern China generally have a better health outcome than individuals from other regions. In addition, in that population-based study, age-standardized disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for AD and other dementias were significantly lower than expected in Shanghai in 2017, in which the ratio of observed to expected difference in DALYs was only 0.69.Reference Zhou, Wang and Zeng7 (3) Furthermore, most previous studies were conducted in the 1990s. Improved quality of care in clinical practice and better awareness of disease might play a role in the observed reduced mortality in our cohort. As practitioners, the authors indeed note that there are relatively higher levels of diagnosis, treatment, and improved nursing standards for AD patients in Shanghai during the most recent two decades, compared with the two prior decades.

The present study confirms previous studies that found shorter survival time for individuals with AD and comorbid type 2 DM.Reference Helzner, Scarmeas and Cosentino8–Reference Imfeld, Bodmer and Jick11 A previous study determined that the duration of diabetes was an important modifier of dementia onset and survival.Reference Zilkens, Davis and Spilsbury9 Moreover, a history of diabetes may be associated with a faster annual rate of cognitive decline in AD patients.Reference Helzner, Luchsinger and Scarmeas12 DM seems to promote specific neuropathologic processes that contribute to dementia, concurrent with cerebral atrophy, lacunar infarcts, and white matter lesions.Reference Jongen, Grond and Kappelle13,Reference van Harten, de Leeuw and Weinstein14 However, the evidence for an association between DM and cognitive decline in AD patients is contradicted in other studies.Reference Regan, Katona and Walker15,Reference Mielke, Rosenberg and Tschanz16 One hypothesis is that diabetic patients may have more frequently received cardiovascular risk-modifying medications or insulin-sensitizing agents, which might contribute to a slower progression of cognitive decline in patients with AD.Reference Mielke, Rosenberg and Tschanz16 Notably, both AD and DM are chronic diseases that may share common pathologic features,Reference Knowles, Vendruscolo and Dobson17 where there is mounting evidence of brain glucose dysregulation in AD.Reference An, Varma and Varma18 In our view, insulin resistance and abnormal glucose metabolism of pre-existing type 2 DM patients may influence insulin sensitivity in brain and aggravate β-amyloid accumulationReference Han and Li19 and, consequently, accelerate the progression of AD.

Consistent with previous studies, lower MMSE score indicated a higher risk of death.Reference Go, Lee and Seo10,Reference Zhao, Zhou and Ding20 Notably, patients with faster cognitive decline tend to have significantly lower MMSE score at the time of diagnosis of AD.Reference Carcaillon, Pérès and Péré21 Another cohort study on mortality risk after diagnosis of various types of dementia demonstrated an association between worse baseline cognition (as represented by MMSE) and higher risk of death.Reference Garciaptacek, Farahmand and Religa6 Interestingly, both age at onset and age at diagnosis are not associated with mortality in AD in our study.

In the present study, sex and education levels were not significant risk factors impacting AD patient survival. Although we presently found that AD increased mortality risk more significantly among women (SMRs of female AD patients are 1.593 (95% CI 1.129–2.183)), this controversial result could be related to the fact that males in general already have an elevated mortality risk and a reduced life expectancy compared to females. For this reason, significant sex differences of survival have not been observed, although our results are consistent with a 15-year epidemiological study.Reference Ganguli, Dodge and Shen22

Limitations

Our study is one of the few mortality studies focusing on AD and, to our knowledge, is the first long-term follow-up prospective study of mortality in Chinese AD patients to date. Mortality data obtained from a national death registry are accurate and reliable. However, our study also has limitations. First, selection bias is inevitable in this clinic-based study, as community patients are different from those seeing specialists, but the survival trends for both groups have been reported to be similar.Reference Zhou, Wang and Zeng7 Additionally, the survival rate was similar for patients with AD compared to the general population in our study, and this may be due to insufficient follow-up time (only 10 years) and the exclusion of the oldest AD patients (>90 years old) from the follow-up subjects, according to NINCDS-ADRDA criteria of AD.Reference McKhann, Drachman and Folstein4 Second, our sample size is relatively small. Last, the factors associated with death reported here are values taken at baseline and do not take into account possible changes in some factors over time. Given that other cognitive scales were not used, and potential confounding variables were not measured or were measured incompletely, future prospective studies should investigate mortality with a more comprehensive cognitive evaluation and more sophisticated analytical methods and larger sample sizes.

Conclusions

This study suggests that AD patients seem to have no significant difference in survival from that of the general population in the urban region of Shanghai (based on the China Public Health Statistical database). However, poor cognitive status and comorbid diabetes are risk predictors for poor survival. Therefore, our study suggests that interventions for these risk factors should be tailored for specific AD patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the patients for their participation in this study.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81671043), the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission-Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant Support (20172001), and the “Shuguang Program (16SG15)” supported by the Shanghai Education Development Foundation and the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission.

Disclosures

All authors have no disclosures to report.

Statement of Authorship

RJR, GW, and QHG conceived and oversaw the writing; YQZ, CFW, and GX contributed to the writing; QHZ, XYX, HLC, and YW each reviewed, critiqued, and edited the manuscript.

Ethics Approval and Consent

The study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Rui Jin Hospital affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China.