1 Overview

China, as one of the world’s largest creditors, has recently faced numerous defaults on its loans by recipient states, bringing the issue of Chinese debt restructuring to the forefront. This case study unpacks this process, with a particular focus on Zambia, a country emblematic of the broader dynamics at play. The primary aim is to elucidate the mechanisms and negotiations employed by China, a major global creditor, in debt restructuring agreements with low-income countries, with an emphasis on its engagements in Africa.

The case study starts with a deep analysis of the Zambia case, highlighting the negotiation tactics and terms of agreements between Zambia and China. This serves not only as a snapshot of China’s dealings with a specific country but also as a springboard for broader discussions. Subsequently, the case study broadens its scope to encompass China’s lending dynamics in the African continent. It dissects the patterns, similarities, and disparities in China’s lending practices across different African nations, elucidating the motives and implications.

Furthermore, the case study establishes a global context by acknowledging China as the world’s largest official creditor. It critically questions China’s choice to remain outside the Paris Club and considers China’s inclination or aversion toward coordinated debt restructuring.

Relying on primary sources from the Paris Club, World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the Chinese and Zambian governments, this case study ensures a robust and credible analysis. While the term “sovereign debt” is used in this case study, it is noteworthy that this terminology is not universally applied in the aforementioned discussions, indicating a divergence in the lexicon across different platforms and analyses.

2 Introduction

In November 2020, Zambia, a landlocked country in south-central Africa, defaulted on its sovereign debts – debts incurred by a government through borrowing from external lenders to finance national projects and programs. As the first African country to default on its Eurobonds during the COVID-19 pandemic, Zambia has struggled with large debts and a lack of foreign currency, making it difficult to purchase necessary products and repay its debt. China is Zambia’s largest sovereign creditor, meaning it is the largest external entity to which Zambia’s government owes money, holding almost one-third of the country’s total external debt.Footnote 1 In addition to being the largest sovereign creditor to Zambia, China is the second largest sovereign creditor in the world after the World Bank.Footnote 2

This case study examines ongoing debt restructuring in China and Zambia, focusing on China’s policies, practices, and approaches to debt restructuring in low-income countries. The analysis acknowledges the challenges in sourcing information, given that much of China’s debt is considered hidden.Footnote 3 Thus, the analysis is based on primary sources from the Paris Club, the World Bank, the IMF, and the governments of China and Zambia, juxtaposing their records with the less transparent aspects of China’s lending practices. This case study highlights China’s extensive lending activities to numerous countries, thereby establishing its position as the world’s largest sovereign creditor. Moreover, this case study will explore how the sovereign debt restructuring between China and debtor countries, including Zambia, lacks a coordinated approach, reflecting China’s tendency to negotiate debt agreements bilaterally rather than through multilateral frameworks.

Such a case study is significant because it provides insight into how China can negotiate with its debtors without becoming a permanent member of the Paris Club, an informal group of major creditor countries established in 1956 that have historically coordinated sustainable solutions to payment difficulties faced by debtor countries. The Paris Club plays a crucial role as a forum for debt restructuring negotiations, setting standards for transparency and coordination. However, it is pertinent to acknowledge that in some developing countries the Paris Club is perceived as being a club for former colonial powers. This perception suggests that the Paris Club may not always align with the best interests of recipient countries, a factor that shapes diverse global views on its role. This case study will provide detailed information on whether China is interested in coordinating debt restructuring and why China has not become a permanent member of the Paris Club. It discusses China’s approach to sovereign debt restructuring and the implications for countries from the Global South. In doing so, it will also shed light on the broader discourse around international debt relief and creditor–debtor dynamics. In addition, it will explain China’s status as the largest sovereign creditor and the likely impact of its policies on the world economy.

3 The Case

3.1 Background on the Economic and Political Context in Zambia Leading to Debt Restructuring

Zambia has a severe debt crisis, with more than half of its tax income going to debt repayment and a budget deficit of 9.5% of its GDP in 2022.Footnote 4 This high level of debt has rendered the government unable to pay its debts and import essential goods, resulting in a foreign currency shortage and a halt in economic growth. Several reasons, including government expenditure, declining commodity prices, and the COVID-19 pandemic, have contributed to Zambia’s debt crisis. Although the pandemic has exacerbated the country’s debt problems, it did not cause them. In recent years, Zambia has been confronted with a variety of economic issues, including a drop in copper prices (the main export), and these problems have been exacerbated by a lack of economic diversification and bad administration. President Edgar Lungu and his party, the Patriotic Front (PF), are primarily responsible for these difficulties.

Prior to 2011 when the PF came to power, the Zambian economy was enjoying growth and stability. The country’s GDP was growing at a constant pace, fueled by the copper mining industry and international investment. In addition, the government had undertaken economic measures that assisted in reducing poverty and improving the living conditions of many Zambians. However, since coming to office in 2011, President Edgar Lungu and the PF have pursued policies and taken actions that have increased the country’s debt, including expanding its use of Chinese external finance to support public works.

The IMF has highlighted the growing debt of Zambia and the prospect of debt distress. In 2017, it warned that Zambia’s debt levels had become unsustainable, and that the government was in danger of defaulting on its debts.Footnote 5 The IMF further noted that the country’s debt issue is exacerbated by the government’s significant borrowing to fund infrastructure projects.Footnote 6

According to the World Bank, the public external debt owed by the Zambian government is US$24.05 billion,Footnote 7 whereas only US$13.04 billion of external debt is reported by the Zambian Ministry of Finance and National Planning.Footnote 8 Although there are loans that have been authorized but do not yet appear in official figures, this large difference suggests a lack of transparency about the external debt. The China-Africa Research Initiative at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies has noted that official sources, which include the World Bank and the Zambian government, have not yet provided accurate information on the stock of debt owed by Zambia to Chinese lenders. Based on open sources and interviews, they suggest that the government of Zambia, including its state-owned enterprises, owes Chinese creditors approximately US$6.6 billion as of August 2021. This is nearly double the amount cited by the Zambian government; its Annual Economic Report 2021 disclosed that the country’s public external debt stock from China, specifically from the Export-Import Bank of China (Exim Bank) and the China Development Bank, stood at US$3.349 billion in 2021.Footnote 9

Based on the above figures, it is estimated that approximately 30% of Zambia’s total loans are attributable to China. Most of these external sovereign debts are owed to China for infrastructure projects, leading to speculation that any debt restructuring with China could involve handing over roads, airports, or even mines.Footnote 10 On 22 June 2023, Zambia struck a deal to restructure US$6.3 billion in debt owed to governments abroad, including China.Footnote 11 To combat the country’s debt crisis, the Zambian finance minister has taken a number of steps, such as suspending certain projects, seeking the advice of debt advisors, and engaging in negotiations with China.

There are possible ripple effects from Zambia’s debt default that may affect other countries. It is certain that Zambia’s economic growth and development will be hampered by the state’s inability to gain future access to international credit markets due to the default. Beyond Zambia, its defaulting on debt might also trigger global financial instability by raising concerns about the ability of other developing countries that have borrowed heavily from China to repay their loans. It might also disrupt countries and sectors that rely on Zambia’s economy, such as mining and agriculture. In addition, if Zambia were to default on its debt, it may have a negative impact on international trade and investment.

3.2 China’s Lending Practices in Africa and Related Concerns

A comprehensive assessment of the debt restructuring process between Zambia and China requires understanding China’s lending practices in Africa and their possible influence on states like Zambia. As Zambia is presently facing a debt crisis and has been highly reliant on Chinese lending, it is essential to evaluate how these lending practices affect the difficulties and opportunities African states have in managing debt and supporting economic development. China has extended large-scale loans to Zambia to fund its infrastructure projects as part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), prompting scrutiny in recent years of China’s lending practices in Zambia, as well as across Africa. The BRI aspires to construct infrastructure to help promote commerce throughout Asia, Europe, and Africa, with China positioning itself as a significant lender of finance to African countries, such as Zambia, to accomplish this objective.

There are rising concerns over China’s general sovereign debt practice, as issues have been raised about the terms of loans, the sustainability of projects, and the potential for debt distress in African countries.Footnote 12 Notably, China’s sovereign debt practice in Africa has been different from those of conventional lenders. First, Chinese official loans offered by the Chinese government are often not as transparent as those provided via commercial channels. Chinese contracts tend to incorporate atypical confidentiality clauses, which prohibit the sovereign debtors from divulging not only the terms but also the very existence of the indebtedness. Moreover, dispute resolution mechanisms stipulated in these contracts often favor Chinese courts or arbitration institutions, potentially disadvantaging the debtor nations.

Moreover, Chinese financiers endeavor to secure advantageous positions relative to other creditors by employing security arrangements such as financier-managed revenue accounts and commitments to exclude the debt from aggregate restructuring (commonly referred to as “no Paris Club” clauses).Footnote 13 Additionally, clauses pertaining to cancellation, acceleration, and stabilization within Chinese contracts grant the lenders the potential to exert influence over the debtors’ domestic and international policies.Footnote 14 This combination of confidentiality, preferential standing, and policy influence may curtail the sovereign debtor’s avenues for crisis management and add layers of complexity to the renegotiation of debt.Footnote 15

Because China is Zambia’s largest creditor, and there is a perceived lack of transparency in its financing practices in Africa, allegations of engagement in debt-trap diplomacy arise as seemingly valid concerns. The term “debt-trap diplomacy” refers to the theory that a state, in this case China, provides loans to other states with the purpose of trapping them in a cycle of debt and then using that debt as leverage to obtain control over the states’ resources or political decisions. There is a widespread perception among journalists and politicians that Beijing utilizes foreign assistance (including both commercial loans issued by state-owned financial institutions and sovereign credit) to prop up rogue regimes or to control other nations via debt. While this claim has been widely circulated, it is important to critically examine the basis of these allegations.Footnote 16 Accessing comprehensive data on China’s financial aid programs is challenging, as the information is fragmented across thousands of documents in various languages, making it difficult to draw conclusive insights.

Although China lends money commercially, it does not publish information about its commercial lending operations or disclose information about its assistance programs via international reporting systems like the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD’s) creditor reporting system. In addition, it uses stringent confidentiality rules to keep its lending and financing operations under cover. Even though the Chinese Ministry of Finance publishes statistics on the state’s overall foreign aid spending, there is a lack of official information that offers a project-level or country-by-country breakdown of foreign lending. This has prompted concerns over the lack of openness and accountability in the lending procedure and the possibility of corruption. Yet a recent study suggests the evidence basis for examining the aims and impacts of China’s sovereign debt practice can be formed by “employing a new set of data collection methods.”Footnote 17

For example, using an innovative suite of data gathering techniques, AidData has compiled an invaluable dataset spanning three years.Footnote 18 This dataset contains details of 100 Chinese loan contracts involving 24 countries classified as having low to middle incomes and can be used to provide novel insights into the intricacies of China’s lending customs. In parallel, AidData, in collaboration with the Center for Global Development in Washington, the Kiel Institute in Germany, and the Peterson Institute for International Economics, undertook a rigorous comparative analysis of Chinese loan contracts and compared them with those furnished by other principal lenders. Through this method, they assessed the legal stipulations in China’s loans. By employing these cutting-edge data collection methodologies and rigorous analytical techniques, Chinese lending practices in the global arena can be better understood.

It is important to note that the conditions of China’s loans have benefited developing countries in Africa as they tend to have low interest rates and lengthy payback periods. This has made them appealing to African states, which have traditionally struggled to get financing from other creditors on favorable terms. Also, there are concerns that African states may become over-indebted and unable to repay their debts. Indeed, this seems to be the situation in Zambia, highlighting the complexity and risks associated with foreign debts, especially for countries with fragile economies.

China’s funding has been motivated by a desire to secure access to African states’ natural resources, including oil and minerals. This has prompted fears that African states may grow reliant on China and lose sovereignty over their natural resources. China’s financing policies in Africa have been marked by a lack of transparency, preferential loan conditions, and an emphasis on acquiring access to natural resources. However, an analysis of the lending patterns in relation to the locations of onshore deposits of petroleum, gold, gemstones, and diamonds has revealed that, despite the possibility of China’s lending practices being motivated by a desire for resources, there is no correlation between these natural resources and the direct outcomes of the loans.Footnote 19 This suggests that China’s motivations may be multifaceted and not solely driven by resource acquisition. However, it is vital to consider the broader implications and strategic interests that might be at play, even if the loans themselves do not yield immediate gains for China.

Further, it is essential to emphasize that Zambia’s debt situation has several causes and cannot be attributed exclusively to China’s lending policies. Poor financial management, wasteful politics, and a short-sighted pursuit of money have all contributed to the country’s present debt dilemma. Regarding Zambia’s development goals, former and current Zambian leaders appear to have a forward-looking development plan centered on infrastructure investment. It is important to note that under the new leadership of the United Party for National Development, the economy is showing resilience. Real GDP growth is now projected to be 4.7% in 2024.Footnote 20

3.3 China’s Sovereign Debt Restructuring Practices

Sovereign debt restructuring is defined as a process wherein a sovereign state renegotiates the terms of its debt obligations with creditors to ensure sustainability and manageability. This usually happens when a sovereign state is unable to meet its debt obligations or is facing imminent default, and it may involve reducing the principal amount, extending maturity periods, or lowering interest rates. Such a process involves “an exchange of outstanding sovereign debt instruments,” which is used by sovereign entities to avoid the risk of debt default of the existing sovereign debt or defer repayment.Footnote 21 Guzman, Ocampo, and Stiglitz noted that “the current system for sovereign debt restructuring features a decentralized market-based process in which the sovereign debtor engages in intricate and complicated negotiations with many creditors with different interests”; therefore, it often operates “under the backdrop of conflicting national legal regimes.”Footnote 22

With no exception, the current approaches taken by sovereign debtors of China are also decentralized and fragmented. Nonetheless, China has shown a willingness to renegotiate loans, mostly bilaterally, under certain conditions, such as when there is a clear risk of default that may impact its bilateral relations or economic interests. It is crucial to recognize that the differentiation between interest-free and interest-bearing loans is a common financial practice, not unique to China. Interest-free loans often entail less financial burden on the borrower, leading to a more favorable stance toward debt forgiveness by lenders. In contrast, interest-bearing loans, which generate revenue through interest, are usually subject to more stringent negotiations. Within this global context, China’s approach to debt management demonstrates a clear preference for leniency toward interest-free loans in terms of debt forgiveness, as opposed to the more complex discussions surrounding interest-bearing loans. Nevertheless, China has earned a reputation for being a skilled negotiator in the realm of debt discussions, particularly for loans that accrue interest.

Since there is no universal international sovereign debt regime for the BRI, there is increasing concern about current approaches to sovereign debt restructuring. China is now establishing a framework to improve the sovereign debt management system, including practical debt sustainability evaluation standards and a standardized sovereign debt restructuring procedure for foreign sovereign debtors.Footnote 23 This framework is spearheaded by the Chinese national government, aiming for a more streamlined and systematic approach. It encompasses guidelines for debt sustainability assessments and mechanisms for negotiating restructuring terms. However, the framework is still in early stages and its efficacy remains to be tested.

As Zambia struggled with high levels of debt, which subsequently led to its default, the government of Zambia sought assistance in managing its debt burden by requesting a suspension of debt payments through the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI). The primary aim of the DSSI is to address the debt sustainability problems faced by those low and lower-middle income countries during the COVID-19 crisis. Also, the DSSI is “a temporary measure to provide liquidity approved in April 2020.”Footnote 24 In November 2020, the G20 and the Paris Club countries endorsed the Common Framework for debt treatments beyond the DSSI (“Common Framework”), which seeks to “facilitate timely and orderly debt treatment for DSSI-eligible countries, with broad creditors’ participation including the private sector.”Footnote 25 The Common Framework provides a more structural approach for those DSSI-eligible countries to deal with unsustainable debts. Fundamentally, the Common Framework serves as a set of common rules (i.e., a basis of mutual agreement) for G20 countries (including those non-Paris Club members like China), the Paris Club members, and private creditors to deal with unstainable debts owed by DSSI-eligible countries in a more orderly manner.

On 16 June 2022, a group of sixteen countries established a creditor committee under the Common Framework. This is led by China and France, with South Africa serving as the vice-chair, and met to discuss Zambia’s request for debt relief beyond the G20 DSSI (following the guidelines set by the G20 and the Paris Club).Footnote 26 Subsequently, the creditor committee held the second meeting under the Common Framework on 18 July 2022. After this meeting, the committee supported Zambia’s efforts to secure an IMF upper credit tranche program and encouraged multilateral development banks to provide maximum support to meet the country’s long-term financial needs.Footnote 27 Such examples of sovereign debt restructuring between China and Zambia indicate that China is willing to work with other sovereign creditors to restructure the debt rather than handle defaults on its own. This could serve as a precedent for other countries, such as Sri Lanka and Pakistan, with significant debts to China.

Instead of being a permanent member of the Paris Club, China continues to participate in the Paris Club’s negotiation meetings on an ad hoc basis. Using this approach, it can still affect its debtor countries’ decision-making process, including those that sit as permanent members. By joining as an ad hoc member, China does not need to respond to every data-sharing request from other Paris Club permanent members, which is one of the likely reasons why China chooses not to become a permanent member.

The pandemic has to some degree united the interests of different players in the sovereign debt market. Due to the advent of the DSSI and the Common Framework, the distinction between sovereign creditors who are part of the Paris Club and those who do not belong to the current sovereign debt restructuring governing framework has become somewhat blurred. Nonetheless, the existing institutional architecture is inadequate to ensure sustainable debt restructuring and equitable burden-sharing among sovereign debt market players (especially those nontraditional and non-Western countries like China).

3.4 Implications for Zambia and Africa

Zambia’s debt crisis and debt restructuring process have significant implications for the country’s economy and society. In the short term, Zambia is likely to face economic challenges due to the debt crisis, including a decline in economic growth and a shortage of foreign currency. The Zambian government will also have to implement austerity measures to address the debt crisis, which may impact the population’s welfare. In the long term, the debt restructuring process and the terms of the agreement with China will have an important impact on Zambia’s economic prospects.

This scenario calls for a detailed understanding of China’s financial aid to various African states. China is the major bilateral creditor globally and it was estimated that China provided African states with loans amounting to almost US$160 billion from 2000 to 2020, predominantly via its state-controlled banking institutions.Footnote 28 The scrutiny of these lending practices has become more acute as countries like Zambia encounter challenges with loan repayments.

The Chinese government has implemented some measures in an attempt to alleviate the burden of debt, which has included absolving twenty-three interest-free loans extended to seventeen African countries.Footnote 29 This action was part of a commitment made by President Xi Jinping during the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation in 2021. In contrast, China exhibits a more rigid approach concerning the restructuring of debt that constitutes the majority of its loans, particularly those under the BRI. The state typically refrains from divulging the terms of its loans, and its approach to debt relief frequently manifests in the form of extensions in loan maturity or the provision of new loans rather than reductions in the principal amount.

In recent times, there has been a discernible shift in the lending practices of China in Africa. Loans are now disbursed after a meticulous assessment of loan applications and specific schemes. This represents a marked departure from previous practices that largely entailed the allocation of funds for infrastructure. This alteration might signify a more circumspect approach to lending in Africa, which could be attributed to the ongoing crises related to indebtedness. As mentioned, Zambia has reached an agreement to restructure its debt of US$6.3 billion owed to foreign governments, including China. If the debt restructuring is successful and the country can achieve a sustainable debt situation, it will be better positioned to attract investment and promote economic growth. However, if the debt restructuring is not successful and the country is unable to achieve a sustainable debt situation, it may face a prolonged period of economic stagnation.

The debt crisis and debt restructuring process in Zambia also have broader implications for the key challenges that sovereign debt and the decentralized governing framework for sovereign debt restructuring pose to international financial stability. As China is a major lender to many African countries, the experience of Zambia raises questions about the potential risks and benefits of China’s lending practices and approach to debt restructuring in Africa. For instance, this case highlights the need for greater transparency and accountability in China’s lending practices and the need for international coordination in addressing debt crises in countries from the Global South. Specifically, the lack of clarity in the lending terms emanating from China, encompassing aspects such as interest rates and stipulations regarding collateral, holds the potential to place debtor nations in precarious circumstances that are disadvantageous. This highlights the need for China to embrace an approach that is more transparent and that harmonizes with global norms, as such an approach may engender trust and facilitate collaboration. In addition, current efforts at the international level may provide frameworks that extend beyond the provision of solutions to immediate debt dilemmas and establish economic underpinnings for nations burdened by debt. Such an endeavor warrants a joint initiative involving principal lenders, including China, international fiscal establishments, and the governing bodies of the indebted nations, with the aim of crafting unified strategies that alleviate the strains of debt and catalyze economic stability.

4 Conclusion

The debt crisis and debt restructuring process in Zambia have been complex and ongoing, with significant implications for the country’s economy and society. There have also been consequences for other African countries that have received loans from China, and for international financial stability in general. This case study has examined China’s policies, practices, and approach to the debt restructuring of countries from the Global South, explicitly focusing on Zambia.

The analysis of the debt crisis in Zambia highlights the country’s economic challenges, driven by internal and external factors, including government spending, falling commodity prices, and external factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The high levels of debt, the composition of the debt, and the sustainability of the debt have all been major concerns in the country. The debt restructuring process and the terms of agreements with China will have an ongoing and important impact on Zambia’s economic prospects.

In conclusion, this case study highlights the need for greater transparency and accountability in China’s lending practices, and international coordination in addressing debt crises in low-income countries. It also highlights the potential implications of China’s approach to debt restructuring, not only for Zambia but also for other developing countries and the global economy as a whole.

5 Discussion Questions and Comments

5.1 For Law School Audiences

China’s growing economic presence in Africa poses several legal and strategic questions. Its approach to lending in Africa, marked by its distinctive features and strategic implications, warrants critical examination from a legal perspective. The intricacies of China’s lending practices, negotiation tactics, and the controversial notion of debt-trap diplomacy are pivotal topics for discussion in the context of international financial law and policy.

Given the above, discuss the following questions:

1. Which salient characteristics define China’s lending approaches in Africa, and in what ways do these diverge from conventional Western lending mechanisms?

2. In what manner does China’s practices in negotiations with indebted nations deviate from the methodologies deployed by the Paris Club affiliates?

3. Is there an abundance of substantiated evidence buttressing the allegation of “debt-trap diplomacy” pursuant to China’s lending practices in Africa, particularly in Zambia?

5.2 For Policy School Audiences

China’s burgeoning political influence in Africa illuminates a variety of strategic considerations. Its distinctive lending approach in Africa, marked by its unique characteristics and strategic implications, necessitates a comprehensive policy analysis.

Given the above, discuss the following questions:

1. Which factors underlie Zambia’s debt predicament, and what part have Chinese loans played in this context?

2. What are the more long-term ramifications of China’s lending practices and debt restructuring strategies for Africa and the additional nations comprising the Global South?

3. It has been argued that the rise of China, which is purportedly bringing about significant shifts in the global power dynamics, is propelled not only by using debt as a geopolitical policy lever but also by the process of lending money – extending credit to countries like Zambia to boost China’s influence and strategic interests. According to some observers, “[t]he spread of financialization, the modernization of Zambian space, and the competition for authority over the Zambian state’s balance sheet were all enabled by debt. In effect the rise of China was being partially subsidized by the lending of fictitious capital to pay for Chinese goods, services, and even labor.”Footnote 30 Do the aforementioned facts support the assertion that China engages in debt-trap diplomacy?

5.3 For Business School Audiences

China’s growing economic influence in Africa brings to light a range of strategic considerations. Its unique lending approach in Africa, marked by its decision not to accede to permanent membership of the Paris Club, calls for an in-depth analysis from a business standpoint. This choice enables China to function outside the conventional norms pertaining to sovereign debt restructuring, which might accord it augmented latitude in negotiations with debtor countries.

Given the above, discuss the following questions:

1. What plausible rationale could underpin China’s resolve not to accede to permanent membership of the Paris Club? How does this choice bear upon its endeavors in debt restructuring?

2. In respect of fulfilling its objectives and preserving its economic and political clout, how efficacious has China’s approach to sovereign debt restructuring proven?

1 Overview

Sino-African joint ventures (JV) are part of a developing relationship between China and African nations that encompasses a range of sectors and presents opportunities as well as challenges. Chinese investment in Sino-African JVs occurs for reasons such as financial support and strategic partnership to strengthen economic ties with African countries. By engaging in such partnerships, Chinese companies spread their investments across different sectors and regions. However, exiting a Sino-African JV may also be necessary for reasons such as a strategic refocus or business realignment; either Chinese or African parties may wish to exit a JV to focus on areas that are more in line with their changing long-term objectives. However, in the world of JVs, parties often face challenges when attempting to exit a partnership.

ICBC Standard Bank Plc (ICBCS) is a Sino-African JV involving the South African Standard Bank Group (“SB Group”) and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC). The JV provided an opportunity for the SB Group to realize proceeds that would release capital to further its growth strategy across South Africa and the rest of the African continent. China’s ICBC entered into the JV to elevate its global markets capabilities. In recent years, the SB Group has wished to exit the ICBCS JV but is restricted from doing so by the terms of its Sale and Purchase Agreement with ICBC.

This case study affords insights into some of the challenges of exiting a Sino-African banking JV agreement and explores the multifaceted impacts of Sino-African banking JVs. This knowledge is vital for informed decision-making by policymakers, businesses, and other stakeholders involved in these collaborations. The primary sources used in the case study were shareholder cautionary announcements, the Sale and Purchase Agreement, annual reporting statements, and press releases.

2 Introduction

On 8 November 2013, the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) released a Stock Exchange News Service announcement that the SB Group was engaged in discussions with ICBC relating to the potential disposal of its controlling stake in the SB Group’s London banking operation, Standard Bank Plc (SB Plc).Footnote 1 Given SB Group’s narrower strategic focus on Africa, it had reached the potential to create considerably more value through growing its franchise and generating incremental revenues from a wider spectrum of opportunities than were currently available to it.

On 29 January 2014, it was announced that Standard Bank London Holdings Limited (SBLH), a wholly owned subsidiary of SB Group, had entered into a Sale and Purchase Agreement with the ICBC.Footnote 2 The proposed transaction

was to create a Global Markets JV with ICBC, named the ICBC Standard Bank Plc.Footnote 3 The Sale and Purchase Agreement was reached through SB Plc, as the primary legal entity used by the Group’s London-based Global Markets business (“OA Global Markets Business”).Footnote 4 The Group’s African Global Markets businesses worked closely with the OA Global Markets Business to source and distribute African Global Markets Products.Footnote 5

The JV created a “unique and commercially compelling opportunity for the SB Group and ICBC to partner in Global Markets.”Footnote 6 It also benefited from the extensive international networks of both ICBC and SB Group, allowing it to serve clients across different regions and time zones.Footnote 7

However, eight years later, it was announced by the SB Group on 11 March 2022 that it was working to exit the JV.Footnote 8 The SB Group wished to exit the JV but was blocked by the Sale and Purchase Agreement with ICBC. Specifically, the lock-in provisions specified that SB Group was not entitled to sell its shares in the JV until ICBC exercised its right to buy the shares or until five years following the completion of the Sale and Purchase Agreement. The SB Group was also required to hold no less than 20% of its shares in the JV up to seven years following the completion of the Sale and Purchase Agreement.Footnote 9 In 2022, the lock-in provisions had expired, and the SB Group communicated its intention to exit the JV. It also started discussions about selling its shares to ICBC.

This case study considers the challenges of the ICBCS Sale and Purchase Agreement in order to gain a granular understanding of the process of exiting a Sino-African banking JV. It analyzes the nature and objectives of a JV between Chinese and African banks and outlines the terms and conditions of the Sale and Purchase Agreement to lay the foundation for an analysis of the triggers to exit a JV. It also explores the impact of changing circumstances on the objectives of the JV and considers whether there is protection against such changing circumstances, as provided in the Sale and Purchase Agreement. In light of the challenges to exiting a JV, the case study explores the importance of negotiating an exit plan in the face of different objectives, as illustrated by the challenges faced by SB Group and ICBC. Whereas the specific exit mechanisms in the lock-in provisions are not unique to the Sino-Africa banking relationship and are found in such agreements globally, in the context of the ICBCS JV this case study shows how such standard mechanisms serve Chinese long-term commercial and geostrategic interest in Africa over short-term gains.

3 The Case

3.1 Background

Corporations and financial institutions in China, the second largest economy and with one of the fastest growing traded currencies in the world, have been expanding rapidly beyond the national borders.Footnote 10 Considering that China and Africa in particular are increasingly important contributors to the global economy, a partnership between Chinese and African banks was viewed as unique in the banking sector and reflective of new linkages between emerging market economies.Footnote 11 Establishing the platform for a Global Markets partnership between ICBC and SB Group would facilitate the formation of a partnership in Global Markets between the largest banks in China and Africa (see the combined footprint in Figure 5.2.1).Footnote 12 Moreover, ICBC had been the SB Group’s strategic partner since 2008 (see the ICBC Standard Bank Group structure in Figure 5.2.2).Footnote 13 The two groups had cooperated on a wide range of initiatives in Africa and other emerging markets, with a particular focus on growing trade and investment flows between China and Africa.Footnote 14

Figure 5.2.1 Standard Bank and ICBC combined footprint

Figure 5.2.2 ICBC Standard Bank Group structure

3.1.1 Standard Bank Group Limited (SBGL) Growth Strategy

The SB Group, a South African bank with a primary listing on the JSE, can be traced back to the Standard Bank of British South Africa in 1862.Footnote 15 It was established as a South African subsidiary of the British overseas bank Standard Bank in London.Footnote 16 The original London-based business has gone through many changes, including expansion into China. Subsequently renamed as Standard Bank Group Limited, it has been building and operating a London-based Global Markets business, Standard Bank London Limited, since 1992.Footnote 17 It has thereafter served as the hub for the Corporate and Investment Banking (CIB) Division’s expansion into emerging markets outside South Africa.Footnote 18

In June 2005, the bank’s name in London was changed to Standard Bank Plc,Footnote 19 having grown from its African roots to be a significant player in commodity and financial market trading in emerging markets.Footnote 20 SB Plc allowed the SB Group to access global capital markets to facilitate growth and development in Africa, as well as to maintain SB Group’s position as a significant financial market participant in commodities trading.Footnote 21 The London-based business has branches in Dubai, the United Arab Emirates, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Japan, and Singapore. It also has representative offices in several locations such as Shanghai in China.Footnote 22 However, in more recent years, only Shanghai in China has remained relevant to the Group’s strategy.Footnote 23 The other representative offices have been reported to be in the process of being closed,Footnote 24 although the reasons for the closures have not been made publicly available.

Since the global financial crisis started in 2007, SB Plc has experienced significant challenges in adjusting its business model. This was exacerbated by the SB Group’s change of strategy from building a Global Emerging Market banking group to focusing primarily on Africa. These challenges included reduced revenue opportunities following the divestiture by the Group of several other businesses in countries outside Africa, among other factors.Footnote 25 Eventually, in 2011, the SB Group abandoned its strategy to be a global emerging markets player to concentrate on its investments in Africa. In line with other actions taken to restructure the SB Group’s international business and reallocate capital and other resources to deliver on its refined African strategy, the SB Group implemented several initiatives.Footnote 26 Substantive action was taken to reduce both the risk profile and the cost base of SB Plc and other operations outside Africa.Footnote 27

3.2 Objectives of the JV

By introducing ICBC as the majority shareholder in the JV, the partners created a new and larger commodity and financial markets platform and expanded the strategic emphasis for the OA Global Markets Business to focus, in particular, on SB Group partnering with China’s leading banking group.Footnote 28 In combination with the powerful client relationships of ICBC, the JV presented the OA Global Markets Business with promising franchise and revenue growth opportunities, while maintaining the role it performed for SB Group’s African business.

As discussed in the background of this case study, the SB Group’s strategy was to focus primarily on Africa. The proposed JV with ICBC presented an opportunity to realize proceeds on disposal that would release significant capital for the SB Group from its operations outside Africa, which could then be effectively deployed in furthering the Group’s growth strategy in South Africa and across the African continent.Footnote 29 Likewise, it would elevate the operations of ICBC.Footnote 30

3.3 Terms and Conditions of the JV

It was agreed that ICBC would acquire 60% of SB Plc’s fully diluted issued share capital from SBLH for cash.Footnote 31 SB Group completed the disposal of a 60% controlling interest in SB Plc to ICBC with effect from 1 February 2015 as of the “Closing Date” (see Group structure in Figure 5.2.2).Footnote 32 The purchase price was payable by ICBC on the basis of the net asset value of SB Plc, subject to audit verification.Footnote 33 Upon completion of the sale and purchase, ICBC would acquire a controlling interest in the Group’s London-based Global Markets business, focusing on commodities, fixed income, currencies, credit, and equities products. The SB Group would retain a minority shareholding interest sufficient to maintain the continuity of access to this business for the group’s African network and clients.Footnote 34

The completion of the sale and purchase was subject to the implementation of a proposed transaction that was, in turn, itself subject to fulfillment or waiver of the conditions precedent as per the Sale and Purchase Agreement.Footnote 35

Conditions Precedent: The focus of the proposed transaction was the OA Global Markets Business. The implementation of the transaction was subject to the fulfillment (or waiver) of several conditions precedent, such as regulatory approval in multiple jurisdictions.Footnote 36 This excluded the Global Markets business within CIB in Africa, which remained with the SB Group after the completion of the Sale and Purchase Agreement.Footnote 37

A series of steps was undertaken to reorganize the SB Plc Group as a condition to completion of the Sale and Purchase Agreement. These steps had to be effected or completed to the reasonable satisfaction of ICBC.Footnote 38 The reorganization constituted the SB Group, SB Plc, and relevant subsidiaries and operations in the United States and Singapore as a focused Global Markets platform.Footnote 39 In addition to regulatory approval, the SB Group had to remove and close all activities that it currently performed and any previously discontinued activities and legacy assets that did not form part of the OA Global Markets Business. This removal involved SB Plc and its representative offices in any relevant international location.Footnote 40 It was intended that SB Plc and its representative offices would be renamed upon completion of the Sale and Purchase Agreement, to reflect the changed ownership of the OA Global Markets Business.Footnote 41 A newly established UK entity or other SB Group entities would acquire or take transfer of all of the assets, liabilities, and employees of the businesses excluded from SB Plc, prior to completion of the Sale and Purchase Agreement.Footnote 42

Prior to the proposed transaction, the SB Group also transferred SB Plc Affiliates to SB Plc. So as to retain the Global Markets booking capabilities held by Standard New York Inc., Standard New York Securities Inc. and Standard Americas Inc. provided to SB Plc the shares owned by SBLH in Standard New York Inc.Footnote 43 In addition, SB Plc intended to close certain nonstrategic representative offices before completing the Sale and Purchase Agreement.Footnote 44

According to the terms of the Sale and Purchase Agreement, during the reorganization, no “Material Adverse Change” could take effect as of 29 January 2014.Footnote 45 This included a reduction in the net asset value (NAV) of the Standard Bank Plc Group of at least US$100 million and/or a decrease in the actual or reasonably projected revenue of the OA Global Markets Business for the twelve-month period commencing 1 January 2014 for an amount of US$50 million or more.Footnote 46

3.4 The Exit Terms of the JV

There was no prescribed expiration date of the JV term. Rather, the respective rights of ICBC and the SB Group to continue or exit the partnership commenced with the ICBC Call Option, two years after completion of the Sale and Purchase Agreement.

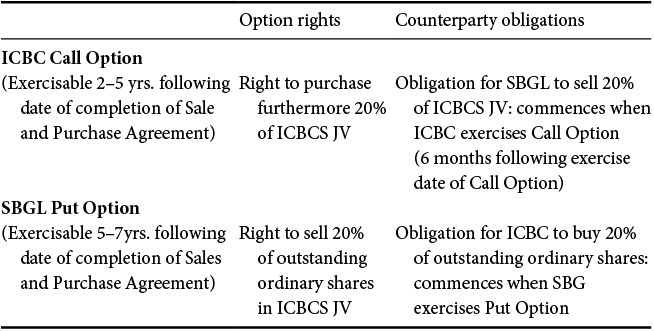

Lock-in provision: The SB Group was not entitled to sell any of its shares in the ICBCS JV until ICBC exercised its Call Option right or until five years following completion of the Sale and Purchase Agreement.Footnote 47 Notwithstanding its rights, the SB Group was restricted to hold no less than 20% of the shares in issue, until the seventh anniversary of completion (see Table 5.2.1 on exit mechanism rights and timelines).Footnote 48

Table 5.2.1 ICBC Standard Bank Plc exit mechanisms

| Option rights | Counterparty obligations | |

|---|---|---|

| ICBC Call Option (Exercisable 2–5 yrs. following date of completion of Sale and Purchase Agreement) | Right to purchase furthermore 20% of ICBCS JV | Obligation for SBGL to sell 20% of ICBCS JV: commences when ICBC exercises Call Option (6 months following exercise date of Call Option) |

| SBGL Put Option (Exercisable 5–7yrs. following date of completion of Sales and Purchase Agreement) | Right to sell 20% of outstanding ordinary shares in ICBCS JV | Obligation for ICBC to buy 20% of outstanding ordinary shares: commences when SBG exercises Put Option |

3.4.1 Exit Mechanisms

3.4.1.1 ICBC Call Option

Commencing two years following the completion of the Sale and Purchase Agreement, ICBC had the right to exercise a Call Option. For a five-year period from the commencement of the Call Option right, ICBC had the right to acquire a further 20% of the outstanding ordinary shares of SB Plc held by SBLH, in cash.Footnote 49 Payable by ICBC, the purchase price for the ICBC Call Option was determined as the higher of “(i) the most recent audited Consolidated NAV of SB Plc attributable to such shareholding, and (ii) the most recent audited consolidated profit before tax of SB Plc, capitalized at a five times multiple, attributable to such shareholding” but subject to a maximum amount of US$500 million.Footnote 50

3.4.1.2 Standard Bank Put Option

In the event that the ICBC Call Option was exercised, SB Group had the right to exercise a Put Option commencing six months after the exercise date of the ICBC Call Option.Footnote 51 Valid for a period of five years, the SB Group had the right to dispose of all its residual shares to ICBC, for cash.Footnote 52 The price of the shares was determined as being “90% of the most recent audited consolidated NAV of SB Plc attributable to such shareholding” subject to a maximum amount payable by ICBC in respect of the SB Group Put Option of US$600 million.Footnote 53

3.5 Changing Circumstances

Owing to changing circumstances in recent years, the ICBCS JV has faced losses that dragged on the SB Group’s earnings.Footnote 54 With the exclusion of ICBCS, the SB Group reported revenue growth.Footnote 55 The Sale and Purchase Agreement protects against changing circumstances prior to approval of the JV. It provides that prior to the completion of the sale of the controlling stake to ICBC, ICBC will have the right to terminate the Agreement in the event of any change in the circumstances that will, or be reasonably likely to have, a material adverse effect on the business, assets, liabilities, condition (financial or otherwise), and/or results of operation of Standard Bank Plc if it is not remedied.Footnote 56 Prior to approval of the JV, an unforeseen matter with potential loss arose relating to SB Plc client exposure at Qingdao Port in China. Certain amendments were agreed to ensure that ICBC did not incur any loss or receive any unintended benefit. Subsequent to approval of the JV, ICBCS incurred a loss as a result of bankruptcy of its client following an explosion at its Philadelphia refinery. Warranties for changes post JV are not provided for in the Sale and Purchase Agreement.

3.5.1 Preapproval of JV

An unforeseen matter arose subsequent to the proposed transaction approval by the requisite majority of shareholders at the General Meeting held on 28 March 2014. In terms of the Sale and Purchase Agreement, the unforeseen matter impacted the disposal of SB Plc.Footnote 57 The proposed disposal by SBGL to ICBC of a controlling interest in ICBCS JV was withdrawn.

On 5 June 2014, the SB Group responded to media inquiries regarding stocks of metal held in bonded warehouses in Qingdao Port in China. These sparked suspicions of fraud, specifically concerning the duplication of warehouse receipts to secure funding from banks, thus allowing huge stockpiles of metals. Banks and trading houses conducted investigations on the security of metal holdings in China, which were also complicated by a cascade of financial deals with clients. The SB Group confirmed that it had commenced investigations into potential fraud at the port, with a potential loss arising from the circumstances.Footnote 58

The SB Group commenced legal proceedings to secure its position with respect to the aluminum.Footnote 59 The aluminum represented SB Plc’s collateral held for a series of commodity financing arrangements, otherwise characterized as repos.Footnote 60 The SB Group CIB discontinued operations, including the fair value adjustment on repo positions relating to aluminum financing in China. It recorded a headline loss of RMB 1,032 million.Footnote 61 The SB Group continued to pursue various alternatives in order to recover the client exposure in respect of this matter.

Notwithstanding the fact that SB Plc was impacted by the valuation of the client exposure, the changing circumstances were not considered material or in conflict with the terms of the transaction as approved by shareholders.Footnote 62 On 10 December 2014, it was announced that SB Group, SBLH, and ICBC agreed to certain amendments to the Sale and Purchase Agreement to ensure that the purchase price correctly reflected the true and eventual net asset impact of the aluminum exposure. The amendment endeavored to ensure that ICBC did not incur any loss or receive any unintended benefit as a result of the relevant client exposure.Footnote 63

3.5.2 Post Approval of JV

3.5.2.1 The US Oil Refinery Deal

In June 2019, ICBCS entered into its first major US trade agreement through a refinery deal with Philadelphia Energy Solutions (PES). The bank brought crude oil to the refinery in order to buy it and then resell refined products. A few days following the deal, the Philadelphia refinery suffered a fire, which resulted in the client filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in July 2019.Footnote 64

ICBCS incurred a loss of US$198 million relating to a single client loss arising from this explosion and the subsequent bankruptcy of its client, PES.Footnote 65 ICBCS also experienced weak conditions across key markets in the base metals business and subdued client activity, causing greater loss to the company.Footnote 66 As a result, the performance of the SB Group was below expectations in 2019.Footnote 67 Were it not for the explosion, the group’s earnings for the year ending December 2019 would have increased.Footnote 68

Although ICBCS’s losses weighed heavily on the group’s performance (as summarized in Figure 5.2.3), the SB Group Chief Executive Officer (CEO) referred to the ICBCS JV agreement, which restricted the group from selling the shares unless ICBC exercised its Call Option rights.Footnote 69 But as “the best outcome for this business … [was] greater with ICBCS,” the SB Group continued support to “get the business to break even.”Footnote 70

Figure 5.2.3 ICBCS annual profit/loss, 2015–2021

3.5.2.2 Ukraine and Russia

The ICBCS JV also faced risks related to exposure to entities that were both directly and indirectly impacted by Russia’s war in Ukraine.Footnote 71 As an emerging markets and commodities business, ICBCS had exposure to such organizations,Footnote 72 but at the announcement of the annual financial results for 2022, it was not yet possible for ICBCS to assess the impact of the war on its performance.Footnote 73

3.6 Exiting the JV

The SB Group has in recent years wished to exit the ICBCS JV and to deploy more capital on the African continent instead.Footnote 74 The JV did not align with its evolving strategy and has been described by the SB Group CEO as “off strategy for us and outside our purpose.” However, the restrictions placed on the SB Group prevented the sale of its shares or interests in the JV for at least five years or until ICBC exercised its Call Option.

The Group CEO indicated that it was unlikely that ICBC would exercise its Call Option until such time as ICBCS was profitable.Footnote 75 In regards to ICBCS, it reported a positive operational performance, contributing to boosting group earnings growth to above those figures recorded at SB activities level.Footnote 76 When ICBC’s Call Option also expired, the SB Group CEO announced during the annual results presentation on 11 March 2022 that discussions had commenced to exit the ICBCS JV.Footnote 77 It was revealed that the bank was trying to convince ICBC to buy its 40% stake in ICBCS,Footnote 78 but no time frame was given. The CEO has been quoted in recent years saying: “As a 40% shareholder we have limited influence on the ICBCS. Nor can we [SB Group] simply cut our losses.”Footnote 79

4 Conclusion

The ICBCS JV case study sheds light on the nature of Sino-African banking JVs. It demonstrates specific relationships between China and Africa, relating to sources of investment and financing for banks in Africa. The status of the ICBC, as a state-owned enterprise (SOE), underscores the significant role of the Chinese government in the JV. The JV may leverage Chinese government support, which often plays a significant role in facilitating JVs in Africa. This relationship is important to both Chinese and African parties but is not without challenges.

Following changing circumstances, the SB Group wished to exit the ICBCS JV in order to achieve its evolving strategic objectives. The main objective of the SB Group, to finance its growth strategy in Africa, had been negatively impacted by the financial performance of the JV. However, the main objective for ICBC, leveraging SB Plc to elevate its own capabilities, has remained relevant. This case study illustrates the challenges with respect to exiting a Sino-African JV, especially between parties that seek to achieve different objectives. It explores the terms and conditions of the ICBCS JV as well as the exit triggers and mechanisms of the African and Chinese parties to the JV. It also queries whether protection is offered to the parties of a JV agreement that takes account of evolving circumstances that may impact the interests of those parties and highlights the need to assess whether the parties mutually benefit from a JV or whether a case of asymmetry exists with respect to changing requirements.

Lock-in provisions typically specify a predetermined period during which parties are restricted from exiting a JV. The lock-in provision in the Sale and Purchase Agreement in the ICBCS JV case study restricted the ability to sell shares with the aim of safeguarding the interests of both parties and promoting a long-term commitment to the JV. The inclusion of a lock-in provision depends on the specific circumstances, goals, and preferences of the parties involved in forming the JV. It is not unique to Sino-African JVs but is a common feature in many similar agreements across different industries and sectors. However, the case study describes how the lock-in provisions serve the Chinese long-term perspective with Africa over short-term gains. Due to restrictive provisions in this particular JV, the SB Group did not have the unilateral ability to exit the agreement until the lock-in period had expired. Eventually, on expiry of the contractual restrictions, the SB Group commenced discussions to exit the JV. The outcome is yet to be determined.

5 Discussion Questions and Comments

5.1 For Law School Audiences

1. This case study highlights the opportunity provided by the ICBCS JV for the SB Group to realize proceeds on disposal that would then release significant capital to be deployed in furthering the Group’s growth strategy in Africa. This raises questions as to the nature of Sino-African banking JVs and their structure (Figure 5.2.2). How does the Sino-African JV align with the bank’s growth strategy in Africa as discussed in the case study? More generally, does the JV capture the relationship of China with Africa, as a source of investment and financing for banks in Africa?

2. The terms and conditions of the ICBCS JV involve various conditions precedent. The case describes a series of steps that were to be undertaken to reorganize the SB Plc Group as a condition for completion of the Sale and Purchase Agreement. Warranties for changes pre approval of the JV are provided for in the Agreement but not warranties against changing circumstances post approval. However, changing circumstances post approval of the JV also modified the performance of the parties and negatively impacted the financial performance of the JV (Figure 5.2.3). Are changing circumstances prior to approval of the JV significant? Are changing circumstances post approval of the JV pertinent or in conflict with the conditions of the transaction?

3. There is no specific expiration date for the ICBCS JV. The exit mechanisms of the JV, such as the ICBC Call Option and the Standard Bank Put Option listed in Table 5.2.1, are discussed in this study. ICBC had the right to exercise a Call Option. The SB Group only had the right to exercise a Put Option in the event that the ICBC Call Option was exercised. Following completion of the JV, ICBC reported the Option was unlikely to be exercised until ICBCS was profitable. Are there any risks or uncertainties associated with these exit mechanisms? Learning from the case study, how effective are these mechanisms in addressing potential challenges, post approval of the JV? Did mechanisms included in the JV Sale and Purchase Agreement protect the parties involved from changing circumstances?

4. The case study sheds light on the challenges faced by SB Group and the restrictions imposed by the terms of the Sale and Purchase Agreement with ICBC. Due to the restrictive provisions of the Agreement, the SB Group did not have the unilateral ability to exit the JV. The lock-in provision, which restricted the SB Group from selling its shares until ICBC exercised its Call Option or after seven years following completion of the Agreement, raises questions about the flexibility and control of the SB Group over its investment. How does the restrictive provision impact the SB Group’s ability to exit the ICBCS JV? How important is it to have a well-defined exit strategy in JV agreements? To what extent does the lock-in provision in the ICBCS JV reflect a balance between short-term gains of SB and Chinese long-term commitment reflected by the strategy of ICBC?

5.2 For Policy School Audiences

1. Foreign direct investment (FDI) can provide both an entry strategy for one organization and access to finance for another. As policies open more sectors to foreign investment, and based on the ICBCS JV, discuss China’s use of FDI in the South African bank, SBG. What are the potential benefits of FDI in the economies of the respective parties to the Sino-African banking JV? Discuss the objectives that China aims to achieve through the use of FDI. Is policy formulation significant in defining the economic value of ICBCS JV? Considering the ICBCS JV case, is there value in policies to promote JVs?

2. This case study illustrates that one approach to FDI is through JVs. From the host government’s rationale, JV policies protect sovereignty by ensuring that foreign investors are restricted from having control over key decisions in the economy. By that rationale, discuss policy options for exit strategies that further promote host state sovereignty.

3. In terms of outbound foreign direct investment (OFDI), both host state and home state governments regulate such projects. Consider both perspectives. What should be the main criteria for host states in approving FDI projects? How does a host state’s relationship with the home state shape such policies? For example, how does the US regulate Chinese FDI versus a country like South Africa? From the home state side, what are the key priorities and how should PRC authorities regulate OFDI? What difference does it make when the JV is based in a third-party state as in this case where ICBC JV is based in the UK? What role should the UK’s policies play in such an instance?

4. Many questions may arise when an SOE and a private enterprise enter into a JV. ICBC is a state-owned commercial bank operating for the benefit of citizens. The SB Group is a profit-driven, publicly listed company that is owned by investors. How does the involvement of SOEs, such as ICBC, in JVs like the ICBCS JV reflect broader government policies and objectives, particularly in the context of long-term Sino-African economic relations? What policies may be essential for the success of the ICBCS JV? Is there a need for specific policies aimed at facilitating such FDI initiatives? How can policies “level the playing field” between private and state-owned firms?

5.3 For Business School Audiences

1. What factors should ICBC have considered when deciding to invest in the JV? Analyze the structure of the JV, as illustrated in Figure 5.2.2, and discuss the alignment of the JV structure with the role of Chinese parties in African banks. How does the JV contribute to the SB Group’s growth strategy in Africa, and how does it position ICBC in the context of its global markets’ capability? In addition to strengthening economic ties, what other assets does ICBC offer that make it an attractive Sino-African banking JV partner?

2. JVs can be a tool for strategic planning such as expanding markets, building capabilities, and aligning goals. The ICBCS JV case describes a series of steps that were to be undertaken to reorganize the SB Plc Group as a condition for completion of the Sale and Purchase Agreement. Explore how the terms and conditions of the ICBCS JV align with the stated objectives of establishing a partnership in global markets. Did the ICBCS JV fit in the wider scheme of the parties’ strategic objectives? Did the parties consider a long-term or short-term view of the JV? How can businesses effectively navigate and address asymmetrical interests and objectives between the Chinese and African partners in a JV, as exemplified by the divergent long-term and short-term goals of ICBC and the SB Group in the ICBCS JV, respectively? Assess how changing circumstances post approval align or conflict with the objectives outlined in the case pre approval of the JV. How did the JV contribute to both SB Group’s focus on Africa and ICBC’s global markets capabilities?

3. Assess the impact of changing circumstances on the performance of the ICBCS JV, both pre and post approval. Consider the conditions precedent and their relevance to the changing circumstances. Are changing circumstances prior to approval significant in the context of JV agreements, and how do they differ from changing circumstances post approval? How do changing circumstances align or conflict with the conditions of the transaction?

4. Evaluate the role and efficacy of the exit mechanisms in addressing potential challenges post approval. Consider the effectiveness of these mechanisms and their associated risks or uncertainties. How do the exit mechanisms in the Sale and Purchase Agreement mitigate risks, especially considering ICBC’s reluctance to exercise the Call Option, most likely until the JV is profitable? Are there alternative exit strategies that could have been considered from a business perspective?

5. Analyze the impact of the lock-in provision on the SB Group’s ability to exit the JV and its control over the investment. Discuss the trade-offs between the restrictive provision and the SB Group’s flexibility. Considering the challenges faced by SB Group due to the lock-in provision, how can businesses entering JV agreements effectively consider and negotiate exit strategies and lock-in provisions?