For the bureaucrats and experts working on population problems in the metropole, total war (1937–45), triggered by the outbreak of war with China in 1937, marked a watershed moment. The Konoe Fumimaro cabinet’s call for general mobilization to construct a “new order” in East Asia changed the official treatment of population issues in a number of ways. First, officials now redefined a large population as an asset and thus adopted a population growth policy.Footnote 1 Second, the government’s demand for a “high-quality” population during the war emphasized the significance of applying eugenics and racial hygiene to the official mobilization scheme.Footnote 2 Third, the government established the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MHW) in 1938 and made it the administrative office in charge of “regulating and utilizing” the population as a valuable “resource” for the nation at war.Footnote 3 Finally, in 1939, the government founded the Institute of Population Problems (IPP) within the MHW as an official institute dedicated to population studies.Footnote 4 The official effort to tackle the population issues in connection with the war culminated in the cabinet approval of the General Plan to Establish the National Population Policy (Jinkō Seisaku Kakuritsu Yōkō) on January 22, 1941. Toward the end of the war, the Japanese government had established what Ogino Miho once called the “system of managing the population under the war,” in which population bureaucrats and experts played a pivotal role.Footnote 5

With the emphasis on population increase and the improvement in population quality, the General Plan to Establish the National Population Policy was instituted in tandem with the eugenic and social policies established during the war, which aimed to primarily promote the health and welfare of women and children. Partly corroborating the Foucauldian theory of biopolitics, and partly the portrayal of wartime Japan as a “fascist welfare state,” the wartime population policy significantly reified the Japanese effort to enhance the reproductive capacity of the “population of Japan Proper” (naichi jinkō) and the colonial subjects, now called gaichi jinkō (“population of the outer territories”), for the eternal existence of Japan as a nation-state-empire.Footnote 6 Yet, the “system of managing the population under the war” was far more pervasive, generating various ways in which the population was articulated and controlled in relation to mass mobilization. One of these ways, which has hitherto enjoyed less attention in historical inquiries, was to regard the population as a composition and to manage the population’s quantity and quality by pursuing a balance in its composition through the population movement.Footnote 7 In the late 1930s and early 1940s, this way of discerning the population and population management manifested in the debate over a “comprehensive population distribution planning” policy, which surfaced as a mass mobilization measure accountable for one of the most important national policies in the total war: “national land planning” (kokudo keikaku).Footnote 8

This chapter is about the policy discussions and research on “population distribution” that emerged in the process of establishing a “national land plan” as a state policy. The population work for “national land planning” effectively illustrates the mode of interaction between science and state-led population management during the war in the context of fascist imperialism.Footnote 9 First, it shows the ways population experts imagined the population as a distributable “ethnic group/race” (minzoku/jinshu) and “resource” (shigen) and how they directly interacted with the Japanese state’s attempts to manage its population for the sake of fascist imperialism.Footnote 10 Second, it illustrates that population science under a dictatorship was, to borrow the words of Sang-hyun Kim, “actively mobilized by the state … to materialize the vision of a self-reliant political economy.”Footnote 11 Under a fascist regime, Japan invested in population research because demographic calculation was perceived to be fundamental for the construction of an economically and politically contained imperium, the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.Footnote 12

One outcome of the state mobilization of population research was the formalization of population studies as an officially endorsed field of inquiry. Another was the expanding role of technical and research bureaucrats in policy-oriented population research. For the most part, these bureaucrats, employed to undertake the state-sanctioned population research, diligently completed the tasks assigned to them. However, a closer look at their research practices also suggests that the knowledge created by population studies was founded upon unstable epistemological grounds, despite the assertion of certainties demanded by the political regime.

From Burden to Valuable Resource: The Population Phenomena in the 1930s

When government officials and population experts raised the issue of “population problems” during policy discussion in the early 1930s, the message they projected had changed little from that of the late 1920s. Their perspective was firmly locked onto the problem of “overpopulation.” The only difference: Policymakers were now wearily tracing the rising discourse of unemployment triggered by the Wall Street Crash of 1929.Footnote 13 Attributing the unstable economic situation that had been in place since the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 to the intensification of the leftist labor movements, these policymakers were worried that mass unemployment, in conjunction with the ever-growing population, might ultimately result in a political crisis. Population experts described this official concern using a blanket term: “unemployment problem” (shitsugyō mondai).Footnote 14

Though not so obvious at first, the issue of overpopulation implicit within the “unemployment problem” was very much a rural economy issue – one specifically linked to the rural community’s inability to absorb a surplus population.Footnote 15 Well before the early 1930s, the population growth rate in “the countryside” (gunbu) was already high, far exceeding that of “the urban area” (shibu).Footnote 16 This trend continued throughout the 1920s, with the rates gradually increasing: from 17.33 per 1,000 population in 1925 to 18.09 in 1930 in the countryside and from 5.60 to 6.92 in cities.Footnote 17 In turn, the rural economy was enduring enormous hardships due to the post–World War I (WWI) depression and the destabilization of economy after the Great Kanto Earthquake. It was also crushed by the volatile prices of rice and silk cocoons, the two major profit-making agricultural products for farmers.Footnote 18 Throughout the 1920s, the countryside was increasingly feeling the pressure of a growing population.

This was the backdrop when the worldwide depression of the early 1930s struck the rural economy in Japan.Footnote 19 From the Malthusian point of view, the economic depression brought a tangible population crisis to the countryside, obliterating the already precarious balance between population growth and subsistence growth. The effect of the collapse of the population-subsistence ratio was felt the harshest in the northern region of Aomori, Iwate, Miyagi, Akita, Yamagata, and Fukushima. The region additionally suffered from severe crop failures caused by cold summers in 1931 and 1934. Yet, in the face of this, the population kept expanding.Footnote 20 A scholar studying the diet in a village in Aomori Prefecture in 1934 lamented that villagers were so desperate that they were subsisting on rotten potatoes and sake lees.Footnote 21 In part to solve this dire situation, throughout the first half of the 1930s, families in the region sent more sons out to work in diversified industries and more daughters off to places, both in and outside of the region, in search of jobs as factory workers, entertainers, waitresses, and prostitutes than ever before.Footnote 22

In this context, experts raised concerns that the “unemployment problem” might further deepen the population crisis in the already debilitated rural community. They feared that the countryside, thus far a major supplier of labor force in cities, might lose an outlet for its “surplus population” due to the economic depression and that the surplus population would disrupt the political order. Official concerns peaked after the attempted military coup d’état by junior army officers on February 26, 1936. High-ranking government officials considered overpopulation, particularly in the farming villages, to be behind the incident, acting as a factor in the political radicalization that caused the attempted coup.Footnote 23 From the perspective of government officials, it seemed obvious that the post–Depression countryside had turned into a problem region due to the growing pressure caused by the expanding “surplus population.”

The government responded to the crisis by further promoting overseas migration.Footnote 24 However, in the early 1930s, Latin America, which by then had become a major destination for the officially endorsed migration project, was becoming less attractive to Japanese emigrants.Footnote 25 During this period, Brazil, the major recipient country in the region, became less welcoming to the Japanese because Getúlio Vargas’s nationalist government, which came into power in 1930, imposed assimilation and exclusion policies on the quickly expanding Japanese migrant communities.Footnote 26 Under these circumstances, Manchuria loomed on the horizon as a new promised land.Footnote 27 The formation of Manchukuo as Japan’s puppet state in 1932 additionally gave the government hope that it could mobilize rural populations to turn Manchuria into an important site of colonial development.Footnote 28 After the Hirota cabinet approved a program for the mass colonization of Manchuria in 1937, local and prefectural organizations arranged a systematic emigration of farmers to Manchuria to establish “branch villages” (bunson).Footnote 29 Posters, travel journals, and historical writings stressed the image of Manchuria as a vast and empty frontier, urging many Japanese to dream of migration as an opportunity to materialize a vision of the future that they thought would be impossible to achieve at home.Footnote 30 For Japanese officials, the emigration of Japanese farmers to Manchuria would buttress what historian Louise Young once called “social imperialism.”Footnote 31 They were convinced that migration was an effective social policy that would relocate a myriad of domestic problems associated with “overpopulation” to Manchuria while also fostering Japan’s colonial development.Footnote 32

Population experts, especially social scientists working on the rural community, were behind the official migration program to Manchuria.Footnote 33 One of the most prominent was the agrarian economist Nasu Shiroshi (1888–1984). Nasu was affiliated with the agrarian movement led by Katō Kanji, a right-wing activist who, in the 1920s, ran schools for rural youth in Ibaraki and Yamagata to realize a farm colonization in Korea and Manchuria.Footnote 34 In the early 1930s, Nasu argued in front of government officials that agricultural migration to Manchuria was an effective way to relieve the population pressure of the resource-poor metropole and simultaneously give hope to the farming villages hardest hit by the depression.Footnote 35 Using his status as a well-reputed academic, in February 1932, Nasu and his colleague Hashimoto Denzaemon consulted with the Guangdong Army (or Kwantung Army, in Japanese Kantōgun), additionally justifying migration on the grounds of security.Footnote 36 Going along with government officials, agrarian population experts stressed that migration was simultaneously a panacea for the domestic problem of “overpopulation” and a tool for the imperial project to turn Manchukuo into Japan’s “life line.”Footnote 37

While the migration program continued into the late 1930s, the official discourse on population problems changed dramatically after the outbreak of war with China in 1937. With the rising demand for labor in the war industry, the narrative of an “unemployment problem” dissipated and was replaced by an argument that stressed the problem of labor shortage. Linked to this, the problem of declining fertility surged as a policy agenda, as mass conscription had a tangible effect on birth rates starting in the latter half of 1938.Footnote 38 The changing political situation in 1938 further exhorted government officials to reconsider population in a different light. In that year, the first Konoe Fumimaro cabinet (est. June 1937) redefined the war with China as a prolonged conflict, and on April 1, 1938, issued the National General Mobilization Law to mobilize the population for the construction of a “national defense state” (kokubō kokka). The demand for total mobilization intensified even more when Konoe issued a communiqué about the Chinese government in November 1938, which stated that the new goal of the current conflict was world peace realized through the “construction of a new order” for “eternal stability in East Asia.” This was immediately followed by another, issued a month later, which stated that the friendship, military collaboration, and economic cooperation of Japan, Manchuria, and China would be ideal for the construction of a “new order” in East Asia. In this political context, a large population size supported by high birth rates, which hitherto had been seen as a socioeconomic menace, was quickly redefined to represent “national power” (kokuryoku).Footnote 39

Also behind the change in the official discourse was an additional understanding of population that had gradually become dominant in policymaking since the interwar period: Population was a valuable national resource. This idea emerged shortly after WWI, when the term “resource” (shigen) entered the official lexicon.Footnote 40 WWI exposed Japan’s shortcomings as a small island nation that was poor in resources. This fostered the consensus, especially within the Army, that the government should invest in resource management to prepare the country for future conflicts.Footnote 41 This view led to the launch of the Cabinet Bureau of Resources in 1927 as the official organization charged with the investigation, management, and mobilization of resources.Footnote 42

The bureau defined resources broadly. According to Bureau Chief Matsui Haruo, “every kind of source contributing to the existence and prosperity of an organization” fell into the category of “resource.”Footnote 43 However, partly because of the army’s involvement in the bureau, Matsui’s seemingly neutral take on the term was full of political overtones.Footnote 44 Indeed, “resource,” as defined by Matsui, referred to materials that could be utilized for the expansion of military power and war industries, and the “organization” was not just any institution, it was the Japanese state preparing for a future war. This interpretation of resource simultaneously gave rise to the idea that the population, too, could be a type of resource. This articulated what Matsui called jinteki shigen (“human resource”), and he insisted that a population, like any other type of resource, could be mobilized for national prosperity. The notion of population as “human resource” was an aggregate of people whose capability was defined not only by size but also by its qualitative values, such as spirit, morality, and physical strength.Footnote 45 In effect, “human resource” for Matsui was human power that directly enhanced the nation’s economic and military capabilities.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, this formulation of population failed to become a mainstream narrative within the policy-oriented population debate, which was overly focused on the problem of “overpopulation.” However, the situation changed in the wake of total war. The concept of population as “human resource” gained currency in a political environment in favor of mass mobilization.Footnote 46 The tendency became prominent, especially after October 1937, when the government merged the existing Cabinet Bureau of Resources and the Planning Agency to create the Cabinet Planning Board (CPB) as the government office charged with resource management and total mobilization. The CPB explicitly understood “human resource” as manpower, a determining factor for the military and labor force being able to sustain the wartime economy and national defense.Footnote 47 This idea of population directly shaped the National General Mobilization Law drafted by the CPB. The law stipulated that “human resource,” juxtaposed with “material resource” (butteki shigen), would be subject to “controlled management” (tōsei unyō) in times of emergency so that the state could fully take advantage of its capabilities for national defense. For the rest of the war, this conceptualization buttressed the central government’s mobilization schemes, such as conscription, the migration of workers, and mass evacuation.Footnote 48

Alongside the rise of “human resource” in the official discourse, the meanings assigned to the growing rural population changed. The surplus population in the countryside, hitherto perceived suspiciously as a seed of political unrest, was now seen positively, as an asset directly assisting the Japanese state’s struggle to win the battle. In parallel, the farming community became described as the primary supplier of a healthy and morally sound “human resource” appropriate for serving the Japanese nation-state-empire. Needless to say, this view did not simply emerge out of a vacuum but was strongly informed by the antimodern, anti-western agrarianism endorsed by activists such as Katō that came to hold currency under the wartime fascist regime.Footnote 49 The ideology denounced cities for fostering western values of decadence, individualism, and liberalism, while romanticizing the farming community as a source of Japan’s national identity and power. When applied to the wartime population debate, the ideology manifested itself in criticism that blamed cities for causing the decline in people’s physical and mental constitutions and blamed the urban lifestyle for the fertility decline. At the same time, the ideology lent itself to the argument in favor of protecting the farming population by means of social policy.Footnote 50 The wartime demand for “human resource,” compounded with agrarianism, invited policymakers to revise their views on farmers. At the same time, the positive view reinforced the existing tendency to regard farmers as a primary target for policy interventions.

Wartime Population Policies: Creating a Large and Robust Population for the Nation at War

The concept of “human resource” amid war highlighted the significance of certain demographic phenomena in the policy discussion.Footnote 51 As already suggested above, fertility decline was attracting the most attention. In fact, even prior to the war, population experts were warning that the birth rate – falling after it peaked in 1920 at 36.19 per 1,000 population – heralded a contracting and aging population in the future.Footnote 52 But, a significant dip in the rates in 1938, from 30.61 the previous year to 26.70 per 1,000 population, was a significant blow to government officials.Footnote 53 They were now worried that Japan would have a less mobilizable “human resource” in the near future. As a MHW document succinctly summarized, the “lack of a population is a lack of military force and workforce,” and the country at war would certainly suffer from the consequences.Footnote 54 Due to this logic, government officials singled out fertility decline as a policy agenda.

Figure 4.1 The trend of birth and death rates in our country. A poster published by the IPP in 1942. The caption states how Japan was following England’s path, and if the trend continued, the Japanese population would start shrinking in 1956. Toward the end, the text below the graph states: “Not only can our imperial race not ignore this situation for our eternal development, but also it needs drastic and further strengthening of population quality and quantity.”

In addition to declining fertility, the “lowering” of the Japanese people’s physical strength caused concern among government officials. The problem of compromised physical strength had been addressed by military health officers since the 1910s (see Chapter 2). In the 1930s, Army Ministry Medical Affairs Director Koizumi Chikahiko (1884−1945) brought the argument to the frontlines of policy discussions.Footnote 55 Pointing to the rising number of men failing the physical examination for conscription due to tuberculosis and substandard muscle and bone strength, Koizumi warned that “physical aptitude” (tai’i) in Japan was in crisis.Footnote 56 He then pointed out that some countries in western Europe, confronted by a similar challenge after WWI, tried to rectify the situation by setting up a government office specialized in nurturing “people’s power” (minryoku) by means of public health and suggested Japan should follow a similar path.Footnote 57 Based on this logic, he urged his seniors at the Ministry of Arms to lobby the government to found what he called the “Hygiene Ministry” (Eiseishō).Footnote 58

What fueled official anxiety even more was the dire state of maternal and infant health in the countryside. This became apparent in the investigation into the demographics and health in approximately 134 villages that the Home Ministry Sanitary Bureau had conducted since 1918 as a follow-up to the HHSG (see Chapter 2). The study, published in 1929, clearly pointed out high stillbirth and child mortality rates in the countryside.Footnote 59 It pointed out that the ten-year average rate of stillbirth in the 7 and 77 villages studied by the bureau and local authorities, respectively, were 2.35 and 2.66 per 1,000 population, which exceeded the national average (2.18) and the average in cities (1.85).Footnote 60 The ten-year average rate of child mortality in all villages in the study was 16.2 per 100 live births, which was more than the national average of 13.7.Footnote 61 This trend alarmed population bureaucrats and experts because these figures revealed that the countryside, supposedly the source of strong, youthful, and high-quality “human resource,” was actually inundated with issues, which could easily lead to fertility decline and falling physical strength, the two biggest demographic problems of the day. They were concerned that high child mortality in rural areas symbolized the imminent future loss of Japan’s “national power.”Footnote 62

The wartime government came up with specific measures in response to these concerns. To accommodate the request from the Army Ministry, the Konoe cabinet authorized the establishment of the MHW, which materialized on January 11, 1938.Footnote 63 The MHW stated that its missions included the improvement of physical strength and maternal and child health to address issues related to fertility decline. In 1939, the MHW assigned the newly established Bureau of Society’s Life Section (Shakaikyoku Seikatsuka) to look into matters concerning population problems, and on August 1, 1941, it launched the Population Bureau.Footnote 64 In 1939, the government also set up the Institute of Population Problems (IPP) within the MHW as a permanently based official institution dedicated to population studies and policymaking.Footnote 65 As historian Fujino Yutaka once suggested, the “policy of cultivating and mobilizing ‘human resource’” under the “fascist regime” urged the wartime government to institutionalize the health and welfare administration and research dedicated to population matters.Footnote 66

Between 1940 and 1941, the IPP was involved in drafting a proposal for population policies, which culminated in the cabinet’s approval of the key wartime population policy, the General Plan to Establish the National Population Policy (Jinkō Seisaku Kakuritsu Yōkō, hereafter General Plan for Population, GPP) on January 22, 1941. The GPP was a direct response to the Outline of a Basic National Policy issued on July 26, 1940 by the second Konoe cabinet (est. July 22, 1940). The outline confirmed the Konoe cabinet’s commitment to the total mobilization for establishing a “new order in Greater East Asia.” It also exhorted Minister of Foreign Affairs Matsuoka Yūsuke to pronounce that Japan’s political goal was to establish a “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” – the term he coined to refer to an economically and politically integrated area in Asia under Japanese leadership – to fend off western imperial intervention and materialize world peace.Footnote 67 On the topic of population, the outline characterized a large and high-quality population as “a driving force for the execution of the national policy” and stated that the government should strive to “establish a permanent policy for population increase, for the improvement in the quality, and for the physical strength of the nation’s people.” Following the outline, on August 1, the cabinet decided that the MHW, CPB, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, and Ministry of Colonial Affairs would draw up a proposal to establish the population policy, while the Home Ministry, Army Ministry, Navy Ministry, and Ministry of Commerce and Industry would act as the main ministries involved in deliberations on the policy.Footnote 68

The GPP, which was made as a result of the interministerial collaboration, stated that it should act as a guide to establish a “fundamental and perpetual population policy” for the “construction and eternal and healthy development of a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.”Footnote 69 It further explained that the population policy should achieve the following four objectives: (1) “to ensure our population’s eternal development,” (2) “to surpass other countries in terms of the population’s growth power and population quality,” (3) “to acquire the required military and labor force for a high national defense state,” and (4) “to appropriately deploy populations to secure Japanese leadership vis-à-vis other East Asian races.” The GPP further presented the following four categories for policy measures: (a) “measures for population growth,” (b) “measures for strengthening population quality,” (c) “the preparation of relevant materials,” and (d) “the establishment of organizations.”Footnote 70

Responding to the outline, the GPP endorsed pronatalism.Footnote 71 It stated that a tangible goal of the current policy should be to increase the “population of Japan Proper” (naichijin jinkō) to 100 million by 1960.Footnote 72 To realize this objective, the GPP proposed the government strive to lower the average age of marriage down by approximately three years and to raise the average number of children per married couple up to five. It further stipulated that these pronatalist measures should be accompanied by others that aimed to lower general mortality by approximately 35 percent over the next two decades. Together, these measures would ensure the growth and perpetual development of the “population of Japan Proper,” thus enabling the population to perform at its full capacity as a “driving force” behind the national mission – so the outline stated.

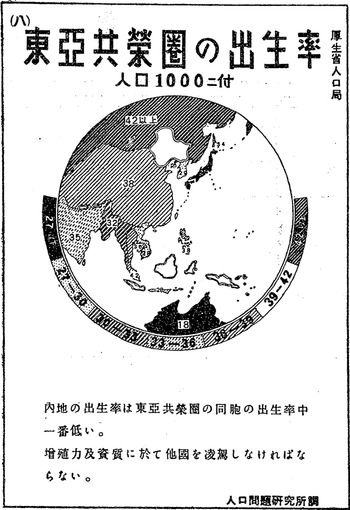

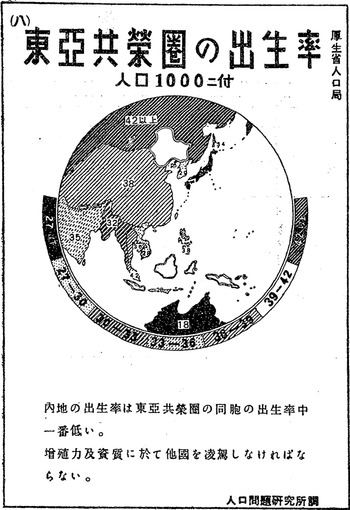

Figure 4.2 Birth rates within the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. A propaganda poster published by the IPP. The caption states: “The birth rate in Japan Proper is the lowest among the fellows in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. We need to supersede other countries in terms of population growth power and quality.”

In addition to pronatalism, eugenics also acted as a backbone for the GPP.Footnote 73 The GPP recommended that the government should “strengthen the physical and mental traits required for national defense and labor” and recommended the “diffusion of eugenic thought” and a thorough implementation of the National Eugenic Law (Kokumin Yūsei Hō), which was issued in May 1940. This eugenic clause in the GPP came in tandem with the MHW’s efforts to popularize eugenics.Footnote 74 From its inception, the MHW had an independent Section of Eugenics within the Division of Prevention. After the government issued the National Eugenic Law and the National Physical Strength Law (Kokumin Tairyoku Hō) in 1940, the MHW instigated the “healthy soldiers, healthy citizens” (kenpei kenmin) movement. This campaign, organized under Koizumi, the new minister of health and welfare, promoted eugenic health and educational initiatives as well as medical research in the metropole and the colonies on topics such as the eradication of tuberculosis, venereal disease control, sterilization, and psychosomatic disorders in order to produce a “physical robust, intellectually sharp, and determined … imperial Japanese population (kōkoku jinkō).”Footnote 75 The GPP placed these measures at the center of wartime population policy.

Though initially only a guideline, the GPP’s status was elevated when Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 turned into a full-blown war involving the Allied Forces. Discourses on race and racism dominated the war, and the government leaders portrayed the population problem even more explicitly as a matter of Japanese leadership in the colored people’s racial struggle against white, western imperialism, which, in the specific context of Japan’s effort to construct a “new order” in East Asia, entailed a struggle that could be overcome through cooperation among the five races in the region (Koreans, Manchurians, Mongolians, Han Chinese, and Japanese).Footnote 76 Under these circumstances, in February 1942, the Konoe cabinet requested the newly founded Advisory Council for the Construction of Greater East Asia (Dai Tōa Kensetsu Shingikai) come up with “population and race policies to accompany the construction of Greater East Asia.” The advisory council’s response, a policy proposal titled “The Population and Race Policy Accompanying the Construction of the Greater East Asia,” stated the main goals of the population policy were to “expand and strengthen the Yamato race” and recommended the government implement the measures introduced in the GPP.Footnote 77 Following the proposal, in November 1942, the government founded the Ministry of Health and Welfare Research Institute (MHW-RI) Department of Population and Race and ordered the new institute to examine the GPP in light of the new policy.Footnote 78 After this, official activities for population and race policies converged more than ever before.

This characterization of population policy – as synonymous with the policy aiming to strengthen the physical and mental capabilities of the Japanese race – was widely shared among high-rank government officials during the war.Footnote 79 It focused on the corporeal aspect of a population and therefore endorsed eugenic, health, and reproductive measures as solutions to the problems of both population quantity and quality. Yet, this was not the only rationale that buttressed wartime population policy.Footnote 80 Another important rationale was summed up in the expression “population distribution,” which allowed contemporaries to expand the scope of their definition of the “population of Japan Proper”: in the context of Japan’s struggles to develop a multiethnic empire with a highly controlled economic system. It also exhorted wartime policy intellectuals and policymakers to ask how the “population of Japan Proper,” as “human resource,” could be best deployed across the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere to maximize Japan’s imperial power. Questions surrounding “population distribution” surged when the government pondered over the population problem in relation to its grand wartime state planning scheme: “national land planning.”

Distributing Populations for the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

As MHW IPP staff were writing drafts of the GPP, their colleagues in the Cabinet Planning Board (CPB) – another office assigned to draw up population policy – were also engaged in population issues. Reflecting the CPB’s role as the cabinet’s war planning and mobilization body, the CPB staff contextualized population problems in terms of the wartime state’s ultimate planning scheme: “national land planning.”

“National land planning” (kokudo keikaku) was conceived sometime in the fall of 1939 as a comprehensive state planning scheme designed for Konoe’s “new order” movement.Footnote 81 It was first discussed in the National Land Planning Study Group, which Konoe’s close advisor Gotō Ryūnosuke created within the Showa Research Association (Showa Kenkyūkai).Footnote 82 Representing the voice of pro-fascist, anti-capitalist “new order” supporters, Gotō claimed the top-down comprehensive state planning ensured by technocratic management was an ideal foundation for the self-sufficiency of the Japan-Manchuria-China Bloc. Responding to Gotō’s call, in January 1940, the association submitted the “Memorandum on National Land Planning,” which triggered policy deliberations within the CPB. The appointment of Hoshino Naoki as the head of the CPB at the inauguration of the second Konoe cabinet in July 1940 gave the policy initiative a boost, since Hoshino had already headed a similar project in Manchuria. The government proclaimed that the “establishment of a national land development plan aimed to expand a comprehensive national power throughout Japan, Manchuria, and China” would be a core policy item in the aforementioned Outline of a Basic National Policy. On September 24, 1940, the cabinet approved the General Plan to Establish National Land Planning (Kokudo Keikaku Settei Yōkō, hereafter the General Plan for Land, GPL), which was drafted by the CPB and based on the Outline of a Basic National Policy.

In a narrow sense, the national land planning delineated by the GPL was an economic policy endorsing self-sufficiency, a means to enhance national productive power via a careful planning of what Ramon H. Myers once called the “enclave economy” of the Japan-Manchuria-China Bloc.Footnote 83 Yet, it was not just a narrowly conceived and managed economic scheme.Footnote 84 “National land planning” was as much a policy of resource economics and national defense as a political technology for constructing a “new order” in East Asia. It involved state bureaucrats’ active participation in the comprehensive development and management of resources in relation to “national land” (kokudo), an ideologically laden, emotive concept denoting the topographical landmass, the geopolitical concept of space, and the source of Japan’s spiritual identity.

A key mandate of national land planning was to adopt a rational approach for seeking an optimal geographical relationship between the “national land” and resources to reach a higher level of efficiency.Footnote 85 To attain this goal, the GPL stressed that the resources acquired within the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere should be distributed “in a controlled manner” and “in relation to the national land,” and assigned the CPB to administer the controlled coordination of resources.Footnote 86

To fulfill the mandate, the GPL adopted the expansive definition of resources expressed by the CPB since the 1920s. They included natural resources (e.g., ore, trees, and water), energy, humanmade institutions, systems such as the industrial system, transportation, cultural and welfare facilities, and, finally, the population. Among these different kinds of resources, the GPL regarded population as particularly critical, thus spending a substantial amount of space elaborating on what it called “population planning,” or the designs for population policies.Footnote 87

As part of national land planning, the primary objective of “population planning” was to raise efficiency through a rational coordination of population and the “national land.” The GPL based on this principle stressed “population distribution” as the chief means for attaining the goal. It stipulated “population planning” should aim for “an appropriate distribution of the population according to regions and professional abilities” and included “comprehensive population distribution planning” (sōgōteki jinkō haibun keikaku) in the list of the nine most important policy items for national land planning. “Comprehensive population distribution planning,” according to the GPL, consisted of the following four interlinked measures: (1) coordination of urban populations, (2) distribution of populations divided by occupational categories, (3) distribution of populations divided by regions, and finally, (4) “comprehensive migration.” In practical term, this entailed the movement of primarily Japanese people within the Japan-Manchuria-China Bloc, or more broadly, the amorphous sphere of imperial Japan’s reach. However, it was not simply an extension of the existing state-endorsed migration scheme. The aim of the existing migration program was to solve the domestic problem of overpopulation by “relieving” the population pressure in the metropole. The “comprehensive population distribution planning” in the GPL was a population growth policy realized through a careful coordination of populations vis-à-vis Japan’s military strategy and the industrial adjustment within the Bloc.Footnote 88 These two migration schemes had different fundamental premises for the “population problem” that necessitated migration.

Having said this, the argument for the “comprehensive population distribution planning” had roots in a number of overlapping discursive sites that thrived in the 1920s as Japan was struggling to build its international reputation as the only nonwestern, industrial colonial power. Among these, two stood out. One was the field of social sciences and social policy that engaged with the population problem as an economic – specifically labor – issue, and the other was geopolitics. As for the first, social scientists serving the IC-PFP Population Section recommended migration in the name of “labor adjustment” (see Chapter 3). Nearly a decade later, social scientists discussed migration again, but this time to tackle the problem of labor shortage and the declining quality of the workforce arising from the rapid expansion of the munitions industry.Footnote 89 The renowned economist Ōkouchi Kazuo argued that these labor problems were inhibiting the expansion of industrial productivity and suggested the government establish social policies aimed at controlling the supply of the workforce as “human resource.”Footnote 90 Partly in response to this kind of argument, between 1938 and 1939, the government issued a number of legislations to manage the labor market, including the amended Work Placement Law (Shokugyō Shōkai Hō) in April 1938 that nationalized the work placement scheme. In this context, government officials redefined work placement as a government initiative to “deploy labor appropriately.”Footnote 91

Corresponding to this trend, social policy specialists examined population distribution as a wartime labor policy, calling it a “deployment of the workforce.” The Labor Problem Study Group, established in February 1939 and consisting mainly of CPB bureaucrats, put forward the “quantitative deployment of labor force” as a specific measure for the wartime economy.Footnote 92 Taking up Ōkouchi’s idea that the wartime labor policy should be a “production policy that seizes workers as its object,” the study group argued that the policy should address the question of “how to distribute the labor force effectively … in relation to the maintenance and expansion of productivity as well as national defense.”Footnote 93 The GPL took up this idea. It explained that one of the policy’s objectives should be “an appropriate distribution of the population according to … professional abilities.” The “population distribution” in the GPL resonated with the narrative of the “deployment of the workforce” that prevailed in the policy discussions on wartime economy.Footnote 94

Another field endorsing “population distribution” for the GPL was geopolitics.Footnote 95 Geopolitics, originally formulated by Friedrich Ratzel, Rudolf Kjellén, and Karl Haushofer, was popularized in Japan in the latter half of the 1920s by figures such as the geographer Iimoto Nobuyuki.Footnote 96 Envisioned at a time when Japan’s international standing was becoming increasingly precarious, geopolitics was depicted in Japan as a theory that justified Japanese imperialism as a colored race’s struggle against western domination in global politics.Footnote 97 After Japan withdrew from the League of Nations in 1933 and began to explore an alternative way to ensure world peace through Pan-Asianism, the academic field called Greater East Asian Geopolitics (Daitōa Chisekigaku) gained political power.Footnote 98 Scholars in the field claimed that Japan, as a country endowed with a special relationship between land and people due to its unique geographical location, was in a fortunate position from which to overhaul the world order currently predicated upon the white-centric Westphalian system. The proponents of Greater East Asian Geopolitics also argued for a construction of a borderless and inclusive Lebensraum in East Asia, united by moral values arguably specific to Eastern philosophies, including altruism and filial piety.Footnote 99 Beginning around 1940, geographers striving to establish the field of Japanese Geopolitics (Nihon Chiseigaku) also promoted the view.Footnote 100 Under the Konoe government, their arguments legitimated the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, as well as the national land planning that aimed to materialize it.

In national land planning, the geopolitical idea of “race/ethnicity/people,” encapsulated in the term minzoku, buttressed the population distribution policy.Footnote 101 Applying the metaphor of “blood and soil” that had been originally presented by Haushofer, Japanese geopolitical thinkers claimed a race (= “blood”) to be a crucial geopolitical actor that maintained a mutually exclusive relationship with the land (= “soil”). Geopolitical thinker Ezawa Jōji equated the “land” with kokudo.Footnote 102 According to Ezawa, people would become minzoku by living in the kokudo. However, kokudo for minzoku did not represent a mere physical space but the “basis of communal affects,” the “externalization of the minzoku’s worldview and … collective experiences.”Footnote 103 Ezawa claimed the relationship between kokudo and minzoku therefore was intimate and powerful precisely because the power to expand the Lebensraum’s boundary resided in the mutually affective interactions occurring within the relationship.Footnote 104 It was this geopolitical formulation of minzoku and kokudo that made “population distribution” an urgent matter for national land planning. Geographer Iwata Kōzō emphasized national land planning should be a plan to attain an “appropriate” (tekisetsuna) relationship between the people and kokudo.Footnote 105 The GPL incorporated this argument when it depicted population distribution. It suggested, with the “population distribution … according to regions,” that the state would guarantee an “appropriate” relationship between the population and kokudo and fuel the limitless expansion of the self-sufficient Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere as Lebensraum.Footnote 106

The geopolitical concerns over race addressed by the GPL made it apparent that the GPL’s policy was indeed part and parcel of the general wartime population policy embodied in the GPP.Footnote 107 Both were premised on the idea that the population policy should facilitate the expansion and perpetuation of the Japanese population as the leading race in Asia. Both incorporated the logic ingrained in the Outline of a Basic National Policy, in particular, that the farming population as the source of Japan’s “national/ethnic/racial power” (minzokuryoku) should be protected through governmental policies.Footnote 108 The GPL’s and GPP’s population policies were synonymous in so far as they both aimed to enhance Japan’s “racial power.”

At the same time, the GPL approached the subject matter differently from the GPP. In contrast to the GPP, whose population measures were informed primarily by the biological model of population-as-race, an economic and geopolitical rationale buttressed the GPL. Furthermore, in part because the GPL concentrated on resource distribution, the GPL population measures endorsed a much more structural understanding of population. Population seen in this light was built on the axis of quality and quantity and made up of individuals with multiple social attributes. This notion of population further consolidated perspective on population quality and quantity that was different from the one that prevailed in the GPP. In contrast to the majority of the population quality measures in the GPP that focused on people’s genetic, physical, and mental constitutions, the population quality described by the GPL was shaped by a balance in the composition of social segments that defined the population. Similarly, while population quantity applied to the eugenic and health measures in the GPP exhorted pronatalism as a strategy for population expansion, population quantity in the GPL, focusing on the ratio of the population numbers in relation to the places of domicile and work, implied that a rational coordination of people’s location according to “regions” and “occupations” was the most effective means to increase a population’s size.

This distinctive approach was most visible in the specific measures the MHW and CPB came up with to tackle the issue of declining fertility among the farming population. While both recognized that the fertility decline among the farmers could weaken the “racial power” of the Japanese, the countermeasures they came up with were different. The MHW, which was involved in drafting the GPP, recommended health and welfare measures (e.g., the prevention of infant diarrhea and the expansion of maternity facilities). In turn, the CPB policymakers, when drafting the GPL, endorsed a controlled migration of farmers between the countryside and cities as well as between the metropole and colonies. To support this measure, the CPB applied the theory established in the early 1930s by the renowned social scientist Ueda Teijirō, who showed a correlation between fertility decline and the movement of people from the countryside to the cities.Footnote 109 In concrete terms, this meant the CPB policymakers deliberated on the migration and work deployment measures to “secure a certain percentage of the population of [Japanese] farmers in farming,” which should be based on the sum of the farmers in “Japan Proper” and those in the Japan-Manchuria-China Bloc.Footnote 110 After much discussion, they settled on 40 percent as the necessary figure.Footnote 111 The different solutions presented by the CPB and MHW in part mirrored the different perspectives of the GPP and GPL, and the different perspectives within the emerging fields of policy-oriented health and the social sciences specializing in population matters.

As a policy initiative, wartime national land planning was a failure.Footnote 112 While the plan was initially moving ahead quickly, in the end, the CPB went only as far as to produce the Proposal for the Outline of the Yellow Sea and Bo Hai National Land Planning in March 1943 and to distribute the Rough Draft of the Proposal and the Proposal for the Outline of Central Planning to various government offices in October 1943 as a policy guideline. The CPB ceased to exist in November 1943, when it was absorbed by the new Ministry of Munitions. Reasons for the policy failure were multifaceted, but internal politics was among the most conspicuous. The struggle for leadership over the wartime economy led to the accusation that communism had infiltrated the CPB, which ultimately led to the arrest of three CPB research bureaucrats for violating the Peace Preservation Law.Footnote 113 National land planning was directly influenced by the dissolution of the CPB after this incident.

In contrast, the “population distribution” policy, originally presented in the GPL, survived in the GPP. The GPP depicted “population distribution” measures as an effective means of achieving one of its stated objectives, namely, “to appropriately deploy populations to secure Japanese leadership vis-à-vis other East Asian races.” It then presented the following two as part of “measures for strengthening population quality”:

(1) [The government should] plan for the rationalization of the population composition and distribution based on national land planning, in particular, [it should] plan for the dispersal of urban populations by means of evacuation. To achieve this, [the government should] do its utmost to disperse factories, schools, and other institutions in provinces.

(2) In view of the fact that the farming village is the most superior provider of military and work force, [the government should] do its utmost to maintain the population of farming communities of Japan Proper at a certain level and to keep 40% of the population of Japan Proper across Japan, Manchuria, and China for farming.

Later, population distribution comprised a core principle in the Population and Race Policy Accompanying the Construction of the Greater East Asia. The proposal contained two clauses, which reiterated the items in the GPP.Footnote 114 Following the proposal, the agricultural policy established on June 24, 1942 by the Advisory Council for the Construction of Greater East Asia stated explicitly that at least 40% of the population of Japan Proper should be comprised of a farming population at all times. In the same month, the government issued a general plan for war mobilization, which in effect banned the building of new factories in the four major industrial areas within Japan Proper. As the war intensified, the population policy initially designed for national land planning became integrated into general war mobilization policies.Footnote 115

The process of making a population policy for national land planning not only highlighted the centrality of the notion of population distribution in the wartime national policy, but it also underlined the increasingly important role scientific investigations played in policymaking: They were conducted by technical and research bureaucrats who specialized in population issues.

Research Bureaucrats for National Land Planning

Albeit a failure as a policy, national land planning highlighted a critical aspect of wartime statecraft: It relied on the brainpower and footwork of bureaucrats. At the top were elite bureaucrats such as Kishi Nobusuke (1896–1987), who drew up national land planning as the ultimate wartime mobilization scheme. They were “reform bureaucrats,” a new generation of state administrators who were defined by their proactive and managerial function and engaged in coordinating work within production and strategic planning.Footnote 116 They belonged to a line of what historian Laura Hein called “reasonable men” with “powerful words,” many of whom spent their formative years at the University of Tokyo where they were exposed to the Marxist social sciences and social movements of the 1910s and 1920s.Footnote 117 These reform bureaucrats thrived in the post-WWI industrial capitalist society, in which the technological advances engendering complex and expensive systems and the perceived decline in liberal capitalism led to an increased demand for a controlled economy and a strong state. During the war, they tried to materialize their technocratic vision of state organization through national land planning. To implement national land planning, they applied the political power derived from the close network of politicians, officers in the Army and Navy, and industrialists and used the state’s power to manage and coordinate industries both in the metropole and for the Japan–Manchuria–China Bloc.

Working side by side with these elite managerial technocrats were the technical bureaucrats called gijutsu kanryō, also known as gikan,Footnote 118 the title given to career bureaucrats who served the government through their medical, scientific or technical expertise. The category was established in the Meiji period, when the new government’s commitment to building a modern nation-state with a technologically enhanced industry and military instigated the training of technically competent bureaucrats. However, technical bureaucrats remained a minority within the state bureaucracy. The demand for them increased in the 1930s, after a report by the Cabinet Bureau of Resources on the poor state of scientific research triggered the move to establish governmental and semigovernmental institutions dedicated to the promotion of science.Footnote 119 After the National General Mobilization Law, technical bureaucrats were sought after even more. Specifically, the Konoe cabinet mobilized them for its “New Order for Science and Technology” (kagaku gijutsu shintaisei), formulated in 1941 to establish the state coordination of scientific and technological activities for rational resource management in both the metropole and its colonies.Footnote 120 In the first half of the 1940s, technical bureaucrats strove to consolidate their status in state bureaucracy by stressing their role as the vanguards of cutting-edge techno-science and by promising Japanese Empire’s self-sufficiency through their involvement in the scientific distribution of natural resources, labor, and capital.

Overlapping with technical bureaucrats was the category of bureaucrats specializing in fundamental research. Known by various titles, such as “research staff” (kenkyūin), “fieldworker” (chōsain), or “research bureaucrat” (kenkyūkan or chōsakan), these research bureaucrats, like technical bureaucrats, were civil servants with scientific expertise and often with a technocratic worldview. However, in contrast to technical bureaucrats, whose expertise was concentrated in highly technical and applied fields such as engineering and medicine, many research bureaucrats had backgrounds in social science.Footnote 121 Moreover, while technical bureaucrats were expected to stay in the same ministry for their entire career, research bureaucrats tended to be hired on a fixed-term basis for a specific project. Thus, many research bureaucrats moved between projects within the same ministry or worked on secondment for a fixed-term technical project organized by another ministry. Depending on the project, public intellectuals and scholars would also be recruited as temporary researchers serving for specific government ministries or other government organizations. In turn, some research bureaucrats, who were affiliated with external organizations accountable for official inquiries, were involved in drafting policy recommendations. In a nutshell, research bureaucrats contributed to state affairs by investigating issues specific to their areas of expertise, mainly for policymaking.Footnote 122

In the national land planning population policy, Tachi Minoru (1906–72) took central stage as a research bureaucrat.Footnote 123 Tachi was a product of the University of Tokyo’s social sciences that generated the “powerful men” mentioned above. He studied economics at the university between 1926 and 1929 and learned about population problems there.Footnote 124 Upon graduation, for over a year he continued his studies with Hijikata Seibi (1890–1975), the soon to be chair of the Department of Economics at the university. After serving as a commissioned editor for Nihon Hyōronsha publishing house for a little over three years, in 1933 Tachi was appointed by the recently founded Foundation-Institute for Research of Population Problems (IRPP) to serve as visiting staff. He then became a permanently based “research bureaucrat” (kenkyūkan) at the IPP when it was established in 1939. In 1942, he became the director of the Division of Population Policy Research of the MHW-RI Department of Population and Race. Shortly after the war, in May 1946, he became the director of the Department of General Affairs at the revived IPP, while still serving as a statistician for the MHW from 1947 on. From the time he assumed the directorship at the IPP in 1959 until his death in 1972, Tachi led population studies in Japan.

Prior to full-scale war with China, Tachi undertook research that became relevant to national land planning in later years. In the mid-1930s, he studied the Tohoku population as a member of the IRPP research staff, engaging with the question of population distribution.Footnote 125 During the war, Tachi collated and compared vital statistics in cities and rural areas, drawing on Mizushima Haruo’s demographic work on six major cities (Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, Kyoto, Kobe, and Yokohama).Footnote 126 At the IPP, along with his colleague Ueda Masao, Tachi compiled standardized birth, death, and population growth rates in every prefecture.Footnote 127 These studies became vital for engaging with the most pressing question for wartime population distribution policy: What percentage of the “population of Japan Proper,” especially the farmers, should be relocated without eroding the population’s ability to expand?

Tachi began to express his opinions on population problems and policies publicly from the mid-1930s onward. He argued that the “population problem” had changed significantly in recent years. Amid the rise of racial struggles, it changed from being an “economic problem” (keizai mondai) to a “racial problem” (minzoku mondai).Footnote 128 Tachi then defined population as something that “organically composes a race or a nation, just like cells compose a biological body.”Footnote 129 In the early 1940s, he suggested the Japanese “race population problem” (minzoku jinkō mondai), related to the construction of “new East Asia,” was a problem of population quantity and quality, and policymakers should take into account the following elements of population: (1) as “military power,” (2) as “members required for the industry,” and (3) as “required for racial [growth].”Footnote 130 Tachi’s understanding of population problems was eclectic, predicated on the idea of population as an organic body and a sociological entity. This multifarious formulation of population informed his engagement with population studies and policies in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Through national land planning, research bureaucrats such as Tachi became a critical cog in the machine driving the Japanese state’s effort to expand the boundary of its nation-state-empire. At the same time, their research helped to establish population studies as a policy science, despite the policy itself failing to materialize.Footnote 131

Population Studies for National Land Planning

Since the 1910s, official investigation into demographic trends and problems was gradually becoming more important in policymaking. After the war with China broke out, the government invested in population research more directly and created the IPP in 1939. In parallel, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Scientific Research (Nihon Gakujutsu Shinkōkai) launched the Eleventh Special Committee in October 1939, which additionally promoted population research as a branch of the committee’s specialization, “racial science” (minzoku kagaku).Footnote 132 On June 19, 1941, experts in racial and population sciences founded the Japan National Racial Policy Study Group (Nihon Minzoku Kokusaku Kenkyūkai) as officially a nonofficial organization studying racial and population policies. The group acted as a policy think tank working alongside the MHW Population Bureau.Footnote 133 By the time the Konoe cabinet approved the GPL, population organizations both in and outside the government had long been fostering policy-oriented population research, creating foundations for population studies to thrive as a policy science.

Under these circumstances, population studies accountable for national land planning took place in three overlapping sites. The first was the CPB, charged with national land planning. Within the CPB, high-rank officials widely shared the idea that fundamental research, including demographic research, was a prerequisite for the government to actualize the vision of total state planning predicated upon a rational management of resources.Footnote 134 However, they also judged the existing research was organized haphazardly by different ministries, and this was preventing efficient planning.Footnote 135 Thus, in the wake of total war, the CPB decided to coordinate the research by making it in-house. It requested the government approve the employment of additional research staff, which was realized in 1937 with the CPB hiring fourteen new personnel members.Footnote 136 Along with this, specifically for population research, the CPB created an independent Population Group within the First Department Third Section and recruited six research bureaucrats.Footnote 137 After the approval of the GPL, the CPB officially made scientific research a part of its administrative work for national land planning.Footnote 138

The MHW IPP was the second site where national land planning population research was conducted. The research began in 1940, after the government published the Outline of a Basic National Policy. While drafting the GPP, IPP research staff collected data and examined subjects they saw as relevant to national land planning.Footnote 139 In October 1940, the IPP made a confidential report, the “General Plan for the Population Deployment as National Land Planning.”Footnote 140 The content of the report fed into the policymaking process and was reflected in the GPP and Rough Draft of the Proposal Outlining Central Planning of 1943.

Finally, the abovementioned research organizations were where population studies related to national land planning thrived during this period. Among them, the IRPP occupied central stage. It hosted the Fourth National Conference on Population Problems between November 14 and 15, 1940 in response to the official inquiry made by Minister of Health and Welfare Kanemitsu Tsuneo.Footnote 141 Following the conference, on December 18, 1940, the IRPP set up the National Land Planning Section Group within its National Population Policy Committee to make the national land planning population research more permanently based in the organization.Footnote 142 Comprised of members from the military, academia, and government offices, and headed by Director of the IRPP Sasaki Yukitada, the section group was a high priority within the IRPP.Footnote 143

Population studies conducted in these sites was integral to policymaking.Footnote 144 The research design drawn up by the CPB for its Population Group, for instance, confirmed population studies’ utility for national land planning. The topics the CPB assigned to the group included “relationship between supply and demand in populations,” “regional distribution of physical strengths according to racial groups,” and “the effect of population concentration and movement (organized by the place of origin and the destination),” which clearly resonated with the demographic goals of national land planning. In turn, these goals directly shaped the objectives of the population research conducted under the aegis of the CPB.Footnote 145 For instance, to correspond with national land planning’s goal for “the optimal location of the Japanese race vis-à-vis other races across the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere,” the CPB stated that its population research, “from the perspective of population expansion and welfare,” aimed to “adequately deploy the population of Japan Proper according to occupations and from the viewpoint of national missions, such as guiding various races in East Asia, promoting industries, development of resources, and the defense of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.”Footnote 146 Population research clearly interacted with the CPB’s administrative and policymaking activities in the state planning scheme. Behind this research arrangement was a trust in population studies within the government administration. The CPB valued the demographic work because it firmly believed that current population research was fully equipped to provide what Sheila Jasanoff once called the “serviceable truth,” the knowledge that “satisfies tests of scientific acceptability and supports reasoned decision making.”Footnote 147 Concretely speaking, the CPB officers were convinced that the demographic knowledge about the population composition produced by population research would effectively assist the government’s decisions regarding a coordinated distribution of the population of Japan Proper, because the idea that mathematical calculation and analysis would reveal the objective truth about the nation had by then reached a firm consensus in the scientific and policy fields. They further believed that population distribution based on this demographic knowledge would help the Japanese to assume the leading role in the construction of a “new order” in East Asia, first by fostering a rational arrangement of economic activities in the Japan–Manchuria–China Bloc and second by ensuring the construction of a hierarchical power structure between the Japanese and other races within the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.Footnote 148 For the CPB officers, demographic knowledge was key to the political maneuverings of the Japanese state and empire at war.

It was in this environment that Tachi thrived as a research bureaucrat engaged in national land planning population studies. Quickly building his reputation within the government and among his colleagues in the 1930s, Tachi was involved in national land planning population work in the CPB, IPP, and IRPP. At the CPB, Tachi was employed on a temporary basis to work in the Population Group and to assume a supervisory role for research on “the form of the decentralization of manufacturing industries and the limits of the urban population.”Footnote 149 At the IPP, he was involved in drafting the “General Plan for the Population Deployment as National Land Planning.” While there, he was also a member of the IRPP National Land Planning Section Group and drafted a policy recommendation document for the Fourth National Conference on Population Problems.Footnote 150 In the early 1940s, Tachi established his name as an expert in national land planning population research by moving agilely between the three institutions and between his roles as bureaucrat, population expert, and policy advisor.

Tachi’s population research for national land planning was motivated by his desire to come up with new planning schemes in alignment with the demands of the “new order” movement and therefore entirely different from the planning work of earlier eras. First, he claimed “comprehensive migration” in the GPL was not the same as the existing migration scheme, arguing that the latter, aiming to relieve population pressure, was based on a Malthusian, “liberalist concept.”Footnote 151 In contrast, “comprehensive migration” was combined with a controlled economy and a migration program that engaged with geopolitical concerns. Second, the government should consider forming “blocs” in the process of implementing population deployment “by regions.” However, unlike an earlier idea, the “blocs” in national land planning should not “foster a mechanical formation of a population group.” Instead, they should form “Lebensraum.”Footnote 152 Third, the “distribution of populations divided by occupational categories” should not be equated with a preexisting work placement scheme.Footnote 153 It should raise “industrial productivity,” but it should not be done at the cost of “consuming the human resource.” For this reason, it should be complemented with welfare measures.Footnote 154 Fourth, the “dispersal of industries” – “dispersing” factories around the nation to “adjust” the population ratio between cities and the countryside – should be conducted with caution.Footnote 155 Fifth and finally, policymakers should factor in the “human aspect,” which had been neglected in the existing planning schemes from which national land planning evolved. For this reason, they should consider building cultural and welfare institutions as a population measure for national land planning. This was important from the viewpoint of racial prosperity.Footnote 156 As Tachi saw it, population measures for national land planning were a “new order” planning policy because they addressed geopolitical and economic concerns as combined factors and maximized the population’s potential in the three domains he elaborated on above – military power, labor force, and the source of “racial power.” This was the reason why they were in no way the same as prewar liberalist population measures.

Tachi’s population work based on this philosophy was wide ranging. He compiled vital statistics and analyzed the patterns of child mortality, age, and gender composition.Footnote 157 He also compiled materials indicating the numbers for the “working populations of Japan Proper” in commerce, heavy industries, ore industries, fisheries, transportation, civil service, freelance work, and housemaid and butler work.Footnote 158 Furthermore, reflecting the centrality of the metropole’s farming population for wartime population policy, he also engaged with the question of how the countryside could act as, what he called, the “imaginary hinterland,” a land supplying populations to cities without destroying its own population’s capacity to grow.Footnote 159 At the same time, Tachi tried to collect demographic materials concerning other strategically important population groups (e.g., Manchurians, Koreans, and the Taiwanese).Footnote 160

Tachi’s work directly contributed to national land planning. The results from the research on the distribution of people in the countryside versus cities were directly useful for the government when trying to decide to what extent it should work toward “dispersing populations of overextended cities … in relation to the dispersion of industries into regions” and “develop the city in a way that it can retain reproductive and growth power” and “prevent industrialization from lowering the population’s power in regional small- to mid-size cities.”Footnote 161 He also used vital statistics to calculate the “excess labor” among the women of Japan Proper and the maximum number of the women mobilizable for war industries.Footnote 162 Vital statistics was also used to ascertain how many people within “Japan Proper” should be relocated between 1943 and 1960 (in the two periods divided by the year 1950).Footnote 163 The data calculated from these works was used to produce the “General Plan for the Population Deployment as National Land Planning.” The document estimated that 85,579,000 should be the minimum population required for Japan Proper in 1950 “for the development of the Japanese race.” Of these, 49,074,000 should be of a “productive age” and at least 35,269,000 workers should be strategically deployed to various industries within Japan Proper. In addition, a minimum of 19,686,000 Japanese people should be based in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, of which 8,111,000 should be in “China Proper” (shina hondo), 6,885,000 in Manchuria, 2,200,000 in Korea, and 2,390,000 in the area covering French Indochina, Thailand, Dutch East India, and the Philippines.Footnote 164 Later, in 1942, for the work the IPP conducted in response to the inquiry made by the Third Section of the Advisory Council for the Construction of Greater East Asia, Tachi recalculated figures for a strategic distribution of the population of Japan Proper. The document concluded that a minimum of 9,410,000 additional people in “Japan Proper” would need to be relocated between 1940 and 1950 to the area covering Korea, Taiwan, Manchuria, “China Proper,” French Indochina, Thailand, Burma, the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, Australia, and New Zealand, and of those, 6,330,000 should be dedicated to agriculture.Footnote 165 The documents became the basis for the recommendations made in the aforementioned Rough Draft of the Proposal Outlining Central Planning of 1943.Footnote 166

As such, population studies conducted by research bureaucrats quickly became institutionalized as the war progressed. Reflecting the government’s trust in population research, the government employed population experts for national land planning and assigned them to provide data on population distribution, which was strategically important for the execution of the wartime national policy. Tachi, as one of the most prominent research bureaucrats in this context, duly responded to the role ascribed to him and produced demographic knowledge that policymakers could utilize readily. The total war fostered a specific form of population studies conducted by research bureaucrats.

However, the political influence on population studies did not end there. National policy also shaped the studies profoundly by exhorting researchers to focus on certain demographic subjects that were particularly pertinent to Japan’s political struggles. In turn, by orienting itself to the policy debate, demographic studies crystallized the racial and gender stereotyping within the characterization of the target population groups in the debate. Consequently, the demographic subjects appearing in the population research were depicted in gendered and racialized terms.

Gendered and Racialized Demographic Subjects

The population research Tachi was involved in was significant, not only because it provided applicable demographic data for policymaking, but also because it elaborated on the demographic subjects who were perceived as threats to the Konoe cabinet’s “sacred mission” to construct a “new order” in East Asia. In the context of national land planning, in which the “sacred mission” was depicted in terms of ethnonational struggles, the identified demographic subjects were also depicted as racialized national groups.Footnote 167

Among them were the populations of western countries vying for power in Asia, in particular the Soviet Union (USSR). Caricaturing the population as “a basis of national power,” population experts showed interest in the Soviet population, especially after the Nomonhan Incident of 1939, in which the devastating defeat in the military confrontation with the USSR dealt the Japanese Army a serious blow. They were particularly concerned that the Soviets would prevent Japan from completing the “sacred mission” with USSR’s expansive landmass and population. Koya Yoshio, Tachi’s colleague at the MHW-RI and one of the most influential technical bureaucrats specializing in racial science (see Chapter 6), claimed the USSR was formidable not only because of its vast landmass but also because of its demographic composition, which was biased toward children and youth thanks to high fertility. In contrast, the Japanese population was meager in size and getting old due to the fertility decline. Comparing the demographic trend of the two countries, Koya warned that the “racially young” Soviets would soon take over Japan’s position as the ruler of Asia.Footnote 168 As Koya saw it, fecundity represented racial vitality and political force, thus the “racially younger” and larger populations of the neighboring countries in Asia, enabled by fecundity, necessarily jeopardized the Japanese influence in Asia.

Population research internalized this logic as it collected the Soviet demographic data in the early 1940s. The MHW-RI Department of Population and Race compiled data about Soviet statistics on birth, death, and natural population growth rates and on the population composition by class, age, and occupation, along with those of other western countries participating in the current war (the United States, England, Germany, and Italy).Footnote 169 In 1943, Tachi, as a member of the department’s research staff, prepared confidential notes showing estimates of the recent population trends in the USSR. For the work, he used the census data from 1897 – since the time of Imperial Russia – population estimates calculated by the USSR and the South Manchurian Railway, and vital statistics produced by the scholar Tachi called “Kuczynski.”Footnote 170

Tachi’s findings about the current state of the Soviet demography were more modest than the alarmist view presented by Koya and other colleagues earlier in the decade. He estimated that the Soviet population had actually decreased from 173,549,000 in 1940 to 171,812,000 in 1943, and would even further decrease to 162,898,000 if soldiers’ deaths from the current war were counted.Footnote 171 He attributed the population contraction to the drastic fertility decline in the 1930s, which occurred despite pronatalist policies.Footnote 172 Tachi also carried out a covert study on the population capable of engaging in (re)productive activities and concluded that “the capacity of the USSR to mobilize human resources has reached a limitation. [Yet] it would not be impossible to expand military mobilization [therefore] we should not see this as a considerable obstacle for [the Soviets] securing a production force.”Footnote 173 Compared to the rhetoric of racial scientists that magnified the racial power of the Soviets, Tachi’s evaluation of the Soviet demography was soberer. However, Tachi’s study also implied that the Soviets were still capable of undermining Japan’s “sacred mission.” In this way, Tachi’s population research consolidated the image of the Soviets as a potential threat to Japan’s political project in Asia.

If the Soviets were perceived as an external threat, Koreans were depicted as a demographic subject destabilizing the Japanese endeavor from within. From the onset of the Japanese annexation of Korea, Japanese-language literary and medical writings pathologized Koreans as prone to crime and depicted this “proclivity” as a factor that would undermine Japanese colonial rule in Korea.Footnote 174 This view, informed by racism, continued into the 1920s within the discussion of “overpopulation.” Confronted with an independent movement, Japanese colonial officers viewed “overpopulation” as a potential catalyst for further political tension that could jeopardize Japan’s colonial rule in the peninsula. At the same time, in the context of the 1920s, in which Japan itself had a growing population and was relying more and more on rice imported from Korea, the population growth in Korea heralded a future crisis in the relationship between the Government-General of Korea and the metropolitan government.Footnote 175 Japanese colonial officials thought the expanding Korean population would erode their effort to build a sustainable relationship between colonial Korea and the metropole.Footnote 176