Substance use by those with severe psychiatric morbidity has been associated with negative outcomes (Reference Swofford, Kasckow and Scheller-GilkeySwofford et al, 1996): even moderate alcohol use is associated with readmission to hospital in the most severely disturbed patients with schizophrenia (Reference Drake, Osher and WallachDrake et al, 1989). In particular, the ability to sustain moderate alcohol consumption is highlighted. Although half to three-quarters of a cohort described as having severe mental illness and past substance use disorders remained in stable remission in the short term (Reference Dixon, McNary and LehmanDixon et al, 1998), longitudinal data for people with severe and persistent psychiatric disorders showed that less than 5% sustained moderate alcohol consumption over 7 years (Reference Drake and WallachDrake & Wallach, 1993). The relationship between moderate alcohol use and outcomes in those with less severe mental problems is yet to be established.

METHOD

Aims

The main aim of the study was to assess the relationship between alcohol consumption categories assessed at baseline and subsequent mental and general health morbidity and mortality in a cohort of people admitted to general hospital psychiatric wards. The secondary aim was to evaluate the development of alcohol use disorders associated with different alcohol consumption levels and reoccurrence of disorders in this cohort.

Design and data collection

The study used a prospective cohort design to analyse the relationship between alcohol consumption level assessed as part of a general hospital psychiatric admission in 1994–1996 and subsequent hospital admissions. Admission data were assembled using the Western Australian Data Linkage System. This can assemble administrative health data from a number of sources and covers the entire population of Western Australia from 1980 onwards (Reference Holman, Bass and RouseHolman et al, 1999). It has been used in a wide range of studies, from identifying post-operative complications (Reference Valinsky, Hockey and HobbsValinsky et al, 1999) to assessing death rates from ischaemic heart disease among psychiatric patients (Reference Lawrence, Holman and JablenskiLawrence et al, 2003).

In 2003 we submitted identifying details on the cohort for record linkage. The requested data covered deaths, specialist mental health unit in-patient and general hospital admissions, including psychiatric admissions. The Western Australian Linkage System contains diagnostic data coded using ICD–9–CM from 1988 to mid-1999 (World Health Organization, 1986) and ICD–10 from mid-1999 onwards (World Health Organization, 1992).

Participants

The participants were 1017 people who had agreed to take part in an earlier study (Reference Hulse, Saunders and RoydhouseHulse et al, 2000; Reference Hulse and TaitHulse & Tait, 2002). They were aged 18–65 years (median 39.7 years, interquartile range (IQR) 31.3–50.0 years) when they were admitted to a psychiatric ward at one of three participating general hospitals between September 1994 and October 1996. Those with poorer courses of disease (more severe conditions or who failed to stabilise) were transferred to a specialist psychiatric hospital and were ineligible for the baseline study and this follow-up study. In Western Australia the specialist hospital is a dedicated facility which includes locked and open wards for long-stay admissions and contains the state forensic psychiatric unit.

In the 5 years before the index admission, 479 participants (47.2%) had had no mental health admissions; the median total days in hospital with a mental health disorder was 1 day (IQR 0–20 days). The median length of stay for the index admission was 14 days (IQR 8–26 days). Participants gave written informed consent, and the study received university and hospital ethics approval. For the current study, access to the Western Australian Linkage System required additional institutional human research and ethics approvals.

Measures

For the current study, alcohol consumption categories of harmful use or dependence were determined by inspecting baseline hospital discharge diagnoses (ICD–9–CM). Those with a diagnosis of dependence or harmful use were assigned to these categories. As part of the baseline study, the level of alcohol consumption by patients was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al, Reference Saunders, Aasland and Amundsen1993a ,Reference Saunders, Aasland and Babor b ) to determine their eligibility for a brief alcohol intervention (Hulse & Tait, Reference Hulse and Tait2002, Reference Hulse and Tait2003). Those without an alcohol use disorder at baseline were classified as abstinent (non-users) if they scored zero on the AUDIT. All other sub-clinical levels of alcohol use were defined as moderate.

We defined mental health admissions as any in-patient admission where the discharge diagnosis included a code from the ICD chapter V (mental and behavioural disorders) (World Health Organization, 1986, 1992). The term ‘alcohol-related admissions’ included all conditions with an aetiological fraction of one (Reference English, Holman and MilneEnglish et al, 1995). This includes conditions such as alcoholic gastritis and alcoholic liver cirrhosis.

Patients on general hospital psychiatric wards typically have a shorter hospital stay and a less extensive history of mental health disorders than those treated at specialist psychiatric hospitals where long-term in-patient treatment and extensive history of disease are common. For heuristic purposes, these groups are respectively described as having ‘less severe’ or ‘severe’ mental health disorders. The term ‘less severe’ also serves to differentiate this cohort from the cohort described by Drake and co-workers (Reference Drake, Osher and WallachDrake et al, 1989) as having ‘severe’ disorders.

Analysis

At all levels of alcohol consumption a proportion of people are likely to have had previous alcohol use disorders. This may be of particular importance for those in the abstinent group, as treatment for alcohol dependence typically recommends zero alcohol use. To reduce the potential for bias associated with this group, we used the Western Australian Linkage System to identify previous diagnoses of alcohol psychosis, dependence or withdrawal (e.g. ICD–9–CM codes 291.0–291.9, 303.00–303.99). A sensitivity analysis was conducted with and without participants classified as abstinent at baseline.

RESULTS

Of the 1017 people screened for alcohol consumption during the baseline study (1994–1996), 1015 were identified by the Western Australian Linkage System and for 996 of these (98%) the index admission was identified. The alcohol use groups comprised 31 dependent, 114 harmful, 621 moderate and 249 abstinent participants. Of the 19 individuals without an identified index admission, 5 were coded as alcohol abstinent and 12 as alcohol users from their AUDIT scores; the remaining 2 (one coded safe, the other harmful) were not identified by the Linkage System. The following analyses were conducted on the 1015 people, of whom 585 (58%) were women. There were 15 624 (median 6, IQR 2–15) post-index hospital admissions, involving 928 participants. The majority of admissions (11 719, 75%) included a mental health diagnosis (median 3, IQR 1–11), such admissions involving 801 people (79%). There were 2253 (median 0, IQR 0–1) alcohol-related admissions, involving 280 participants (28%). Table 1 shows the clinical and demographic features sub-divided according to alcohol consumption groups.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical features by alcohol consumption categories

| Variable | Alcohol consumption categories | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abstinent (n=249) | Moderate (n=621) | Harmful (n=114) | Dependent (n=31) | ||

| Gender, male: n (%) | 89 (36) | 251 (40) | 66 (58) | 24 (77) | <0.001 |

| Age, years: median (IQR) | 47 (35-58) | 38 (31-48) | 38 (30-46) | 45 (35-49) | <0.001 |

| Deaths: n (%) | 28 (11.2) | 48 (7.7) | 11 (9.6) | 6 (19.4) | 0.08 |

| Time to first mental health admission, days: mean (95% CI) | 832 (709-956) | 8992 (816-981) | 745 (562-928) | 3611 (109-614) | <0.005 |

| Mental health admission by 12 months: n (%) | 138 (55.4) | 341 (54.9) | 72 (63.2) | 25 (80.6) | <0.025 |

| Time to first alcohol admission, days: mean (95% CI) | 24113 (2349-2474) | 21372 (2071-2203) | 1211 (1004-1419) | 5111 (212-810) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol admissions by 12 months: n (%) | 6 (2.4) | 67 (10.7) | 51 (44.7) | 22 (71.0) | <0.001 |

| Time to first hospital admission, days: mean (95% CI) | 5904,5 (489-690) | 6162,5 (549-682) | 452 (325-578) | 341 (103-579) | <0.01 |

| Any hospital admission by 12 months: n (%) | 158 (63.5) | 396 (63.8) | 79 (69.3) | 25 (80.6) | 0.178 |

| Pre-index alcohol dependence: n (%) | 12 (4.8) | 13 (2.1) | 15 (13.2) | 14 (45.2) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol use disorder by 7 years: n (%) | 17 (6.8) | 112 (18.0) | 68 (59.6) | 28 (90.3) | <0.001 |

As shown in Table 1, there was a significant association between alcohol use group and gender. There was also a significant association between alcohol use group and age. An inspection of the means suggested that there was not a group by gender interaction. However, violation of the assumptions for analysis of variance (ANOVA) prevented statistical assessment.

Baseline primary diagnoses were grouped via discharge diagnostic codes and tabulated according to alcohol use groups (Table 2). The ‘other mental health’ disorders included 41 poisonings, of which 40 were classified as self-harm or suicide attempts. Notably the dependent group had 12 ‘other mental health’ diagnoses, of which 5 were self-harm poisonings.

Table 2 Alcohol use groups by baseline primary diagnostic category assigned from ICD–9–CM discharge codes

| Baseline primary diagnostic group (code) | Alcohol use group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abstinent n (%) | Moderate n (%) | Harmful n (%) | Dependent n (%) | |

| Schizophrenia (295) | 41 (16.5) | 85 (13.7) | 10 (8.8) | 2 (6.5) |

| Other psychosis (290-299 excluding 295) | 91 (36.5) | 240 (38.6) | 46 (40.4) | 8 (25.8) |

| Stress-related disorders (308-309) | 29 (11.6) | 119 (19.2) | 25 (21.9) | 7 (22.6) |

| Neurotic, personality and depressive disorders (300, 301, 311) | 50 (20.1) | 93 (15.0) | 18 (15.8) | 2 (6.5) |

| Other mental health plus poisoning (960-979)1 | 15 (6.0) | 38 (6.1) | 10 (8.8) | 12 (38.7) |

| Other disorders | 23 (9.2) | 46 (7.4) | 5 (4.4) | 0 (0) |

Mental health admissions

By 12 months there was a significant difference between groups in the proportion that had had at least 1 mental health admission (Table 1), with the moderate group having the lowest proportion of admissions (χ2=10.2 (3), P<0.025). Over 7 years there was a significant difference in total mental health admissions (abstinent group, median 3, IQR 1–9; dependent group, median 8, IQR 4–19; Kruskal–Wallis 15.5 (3), P<0.001). The abstinent and moderate groups had a similar level of admissions (Mann–Whitney U=75 948, P=0.68), but the moderate group had fewer admissions than the harmful group (U=30 880, P<0.05), whereas the abstinent group did not differ significantly from the harmful group (U=12 660, P=0.097).

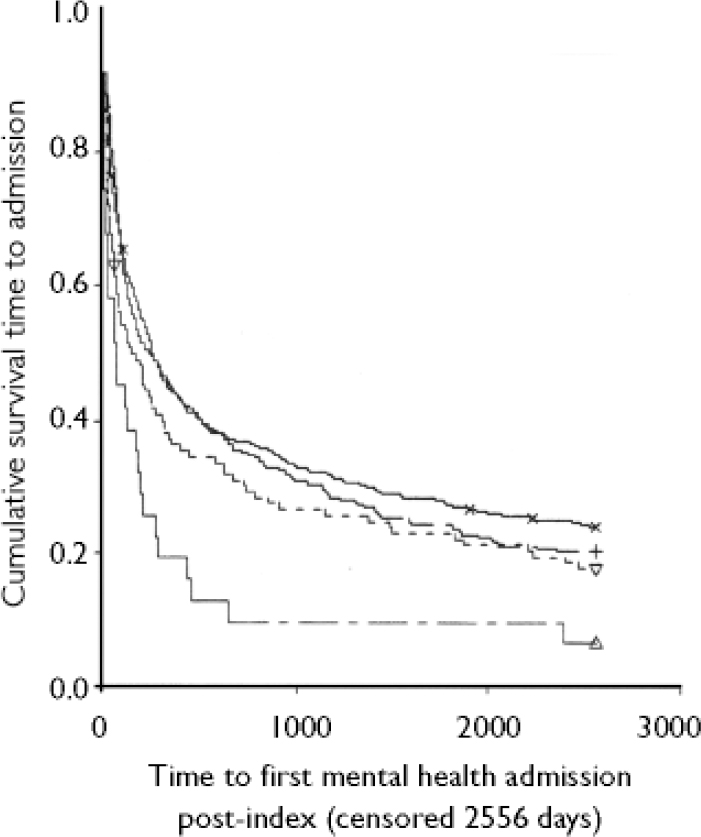

The survival time to first mental health admission was assessed with Kaplan–Meier survival curves (Fig. 1) and log-rank tests. There was a significant difference in survival times across the alcohol use categories (Table 1). By 7 years, only 6% of the dependent group had not had a mental health admission compared with 24% of the moderate group (mean survival times 361 and 899 days respectively). Between groups, the dependent group had significantly shorter survival times than all the other categories. Notably, the only other significant difference between groups in survival times was between the moderate and harmful groups (log-rank test 3.9 (1), P<0.05). There was no reliable difference between the abstinent and harmful groups (log-rank test 1.6 (1) P=0.21). Six cases were censored owing to death of the participant. After adjusting for gender, the same pattern of survival results was obtained.

Fig. 1 Survival time to first mental health hospital admission post-index admission, by alcohol use group:––, abstinent (n=249); +, abstinent-censored; – moderate (n=621); ×, moderate-censored;----,harmful(n=114); ▿, harmful-censored; –, dependent (n=31); ▿, dependent-censored.

Alcohol-related admissions

By 12 months there was a significant difference in the proportion of each group that had experienced at least one alcohol-related admission (range 2.4–71.0%). There was a significant difference between groups in total alcohol-related admissions at 7 years (abstinent group, median 0, IQR 0–0; dependent group, median 5, IQR 2–18; Kruskal–Wallis 206.2 (3), P<0.001).

Survival times to first alcohol-related admission decreased for each increasing level of consumption; the respective mean survival times for the abstinent and dependent categories were 2411 and 511 days (Table 1). A between-groups assessment of survival times found significant differences between all the groups, including the abstinent and moderate categories (log-rank test 18.2 (1), P<0.001). There were 59 cases censored owing to death of the participant, of which 22 were in the abstinent and 34 in the moderate group. After adjusting for gender, the same pattern of survival results was obtained.

All-cause hospital admissions

At 12 months there was no reliable difference between the proportion of people in each group who had had a hospital admission (Table 1), with an unstandardised rate of 62.1 admissions per 100 person-years. At 7 years there was a significant difference between groups in the total number of hospital admissions (Kruskal–Wallis 10.9 (3), P<0.025), with the median number of admissions ranging from 6 (IQR 2–14) for the moderate users to 10 (IQR 6–22) for the dependent group.

There was a significant effect of alcohol use group on survival times to the first hospital admission of any type, with survival time decreasing from moderate through to dependent use (overall log-rank test 12.0 (3), P<0.01) (Table 1). The moderate group had a significantly longer survival time than both the dependent (log-rank test 7.5 (1), P<0.01) and harmful groups (log-rank test 5.1 (1), P<0.05). The abstinent group also had a longer survival time than the dependent group (log-rank test 6.3 (1), P<0.05). By 7 years most people had had at least one admission, the proportion ranging from 97% in the dependent to 81% in the moderate group. Three cases were censored owing to death of the participants. After adjusting for gender, this pattern of survival times was replicated except in that the abstinent group also had a longer survival time than the harmful group (log-rank test 4.4 (1), P<0.05).

Sensitivity analysis: pre-index alcohol dependence

We identified 54 participants (5.3%) who had a previous diagnosis of alcohol dependence at the time of the baseline screening. The number in each alcohol group is shown in Table 1 (penultimate row). After excluding the 12 people in the abstinent group, the above three survival analyses were rerun. In each case the pattern of findings was replicated except in relation to total hospital admissions, where the abstinent group had a significantly longer survival time than the harmful group before adjusting for gender.

Development and recurrence of alcohol use disorders

Of the 145 persons with an ‘active’ alcohol use disorder at index, 96 (66%) had a subsequent admission with an alcohol use disorder. Among the 64 people with pre-index alcohol use disorders, 32 (50%) were in remission at the index admission, of whom 20 (62.5%) were in the moderate group. Subsequently, 12 (37.5%) redeveloped an alcohol use disorder, of whom 10 (83.3%) were from the moderate group. Of the 838 without a disorder before or at index, 117 (14%) were later diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder, 102 (87%) of whom were in the moderate group. Overall, there was a significant difference in the proportion of people with ‘active’, ‘non-active’ and ‘no previous alcohol use disorders’ who developed an alcohol use disorder by 7 years (χ2=200.1 (2), P<0.01).

The final row of Table 1 shows that there was a significant difference in the proportion of each alcohol consumption group that had at least one admission with an alcohol use disorder (dependent or harmful use). Surprisingly, although most of those with dependence had a readmission (28, 90.3%), few had readmission with an alcohol use disorder in the first 12 months (5, 16.1%).

Mortality

There were 93 deaths (48 women (52%)), and those who died were significantly older than those who did not die (median 43 (IQR 35–57) v. 39 (IQR 31–50) years, Mann–Whitney U=36 139, P=0.012). The dependent group had the greatest proportion of deaths (6, 19.4%), but there was no significant association between alcohol use group and death (χ2=6.7 (3), P=0.08). Suicide, as assessed from ICD codes, was recorded for 31 deaths (33%). There was no significant association between suicide and gender (χ2=0.19 (1), P<0.66) and the association between alcohol use group and suicide could not be reliably assessed because of the number of cells with few cases.

DISCUSSION

We investigated hospital admissions over the 7 years after a mental health hospital admission in a cohort with less severe mental health problems (characterised by a limited history of mental health hospital admissions). This cohort was also categorised according to their level of alcohol use at baseline (abstinent, moderate, harmful or dependent). Overall, we found that those with alcohol dependence had worse health outcomes than the other groups. However, there was a high level of morbidity in all groups, with more than 90% of participants having at least one hospital admission. For the general Australian population of the same age range, the rate of hospital admissions varies from about 20 per 100 person-years in those aged 20–24 years to about 40 per 100 person-years in those aged 60–64 years (Reference Glover, Harris and TennantGlover et al, 1999). In this cohort the rate was over 60 per 100 person-years, indicating that those with less severe mental health problems are at greater risk of morbidity and are greater consumers of hospital resources than the general population.

Development of alcohol use disorders and relapse

The ability to sustain moderate drinking is of importance in this cohort, as it has previously been found that those with severe mental health disorders are unlikely to sustain moderate levels of consumption, with about a quarter developing an alcohol use disorder (Reference Drake and WallachDrake & Wallach, 1993). In the current study, less than 2% of abstinent and about 12% of moderate users at baseline developed a first-time alcohol use disorder in the subsequent 7 years. By way of comparison, the estimated lifetime prevalence of alcohol use disorders is 13.5% in the US population and 34.1% in US mental hospitals (Reference Regier, Farmer and RaeRegier et al, 1990). Therefore, those in the cohort without a previous alcohol use disorder have a prevalence of these disorders over 7 years similar to that of the general US population lifetime estimate.

For those with an alcohol use disorder in remission at baseline, 37.5% had a recurrence within the follow-up period, with over 80% of these being from the moderate use group. In those categorised with alcohol dependence, only 16% had a recurrent alcohol use disorder within 12 months, but by 7 years this rose to 90.3%. In the harmful use group the respective figure was about 60%. In contrast, previous research has shown that about 50% of those with a severe mental health disorder and a past substance use disorder are likely to have a recurrence of their substance use disorder within 12 months (Reference Dixon, McNary and LehmanDixon et al, 1998). Accordingly, moderate alcohol use should be discouraged in those with but not those without a history of alcohol use disorders.

Moderate use v. abstinence

A special focus for this study was the possible difference in morbidity between those with moderate levels of alcohol use and non-users. We found no evidence to suggest that those using moderate levels of alcohol were more likely to have mental health or general health admissions or increased mortality than were those abstaining from alcohol. Furthermore, survival to either first mental health or first all-cause hospital admission was similar for the two groups. It was only with respect to alcohol-related morbidity that those in the abstinent group had better outcomes (e.g. longer survival times) than the moderate use group. This result needs to be tempered with the knowledge that only 10% of moderate consumers had an alcohol-related admission in the first year.

There was tentative evidence that moderate alcohol use compared with abstinence was associated with a reduction in mental health admissions. Specifically, moderate users had fewer mental health admissions and a longer survival time before admission than the harmful group. The abstinent group was not reliably different from the harmful group on these measures, although the difference approached significance with respect to the number of admissions. For cardiovascular disease there is now extensive evidence that moderate amounts of alcohol confer benefits, compared with either non-use or heavy use of alcohol (Reference DollDoll, 1998). Given the known exacerbation of symptoms with even moderate alcohol consumption among those with severe mental health disorders, a finding of beneficial out-comes as suggested here for those with less severe mental health disorders needs to be interpreted with great care. These data are, however, consistent with other data from the general population, where moderate drinkers have a lower risk of symptoms of depression and anxiety than either non-users or heavy drinkers (Reference Rodgers, Korten and JormRodgers et al, 2000). They are also compatible with data on dementia in older adults (65+ years), where abstainers and heavy drinkers have a greater risk than moderate (1–6 drinks/day, defined as 12 oz of beer, 6 oz of wine or 1 shot of spirits) drinkers of developing dementia (Reference Mukamal, Kuller and FitzpatrickMukamal et al, 2003). Additional longitudinal data show that as few as 1–3 drinks/day (amounts not defined) reduce the risk of dementia in those aged 55 years and over (Reference Ruitenberg, van Swieten and WittemanRuitenberg et al, 2002).

There are a number of possible mechanisms by which moderate alcohol consumption may affect mental health: for example, via improved general health (cardiovascular health (Reference DollDoll, 1998)) or general psychological well-being (Reference Baum-BaickerBaum-Baicker, 1985). However, these authors caution that moderate alcohol consumption may simply act as a marker for an as yet unidentified causal variable such as social stability. If this were correct, then it would be in-appropriate to view moderate alcohol use as having a protective effect for psychiatric morbidity or to recommend moderate consumption by those with psychiatric morbidity. On the other hand, we suggest that moderate alcohol use should not be actively discouraged as it may assist in maintaining the social fabric. The need for a conservative approach is emphasised by the findings of a recent longitudinal study. This reported unadjusted benefits in relation to depression for moderate alcohol users compared with long-term abstainers, ex-drinkers, heavier-moderate and heavy drinkers, but found that adjustment for a range of socio-demographic and health variables left only the heavy drinking groups at a disadvantage (Reference Paschall, Freisthler and LiptonPaschall et al, 2005).

The inconsistency between our findings and those of a previous study, in which even moderate alcohol use exacerbated symptoms for those with severe mental health disorders (Reference Drake, Osher and WallachDrake et al, 1989), probably reflects differences in the study groups. In Drake et al's study all of the participants had a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia and, although they were recruited as out-patients, they had an extended history of mental health hospital admission (lifetime mean 4.4 years, s.d.=4.9). In contrast, nearly half of the participants in our study had no mental health admission in the 5 years before baseline and about 10% did not have a primary psychiatric diagnosis, although all were admitted to psychiatric wards. We therefore contend that the current cohort depicted here as having less severe illness is markedly different from cohorts previously described as having severe disorders.

Suicides

It has previously been found that people who have been psychiatric in-patients have a suicide rate more than 10 times that of the general Western Australian population (Reference Lawrence, Holman and JablenskyLawrence et al, 1999). Data from the USA have also shown that suicidality is a feature that distinguishes people with alcohol problems with and without depression (Reference Cornelius, Salloum and MezzichCornelius et al, 1995). Therefore the prevalence of suicide in the cohort, although high, is not unexpected. Nevertheless, it does suggest that further research is required to develop appropriate discharge and community support strategies for this population. Surprisingly, in the current study the proportion of suicides among men and women were similar, whereas previous research has shown that men have an elevated risk (3.4 times that for women) (Reference Lawrence, Holman and JablenskyLawrence et al, 1999).

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ The results do not support a general recommendation of alcohol abstinence for people with a less severe course of mental health disorders; indeed alcohol may be a protective factor or a marker for better mental health outcomes in this cohort.

-

▪ Health professionals should still advise individual patients with less severe mental health disorders not to consume alcohol where there are dangers of interactions with medications or where there is a history of previous alcohol use disorder.

-

▪ Health professionals should still treat concurrent alcohol use disorders.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ The participants were not randomly assigned to alcohol use categories, so inferences must be drawn with caution. Also, the diagnostic categories of dependent and harmful use were obtained from discharge codes assigned from clinical diagnosis rather than via research assessment using a standard instrument.

-

▪ Survival analysis assumes that those who are censored would not have had worse outcomes than those remaining in the study.

-

▪ The cohort was described as having less severe mental health disorders, but the extent of severity was not quantified.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Data Linkage Unit at the Department of Health, Western Australia, for assembling the study data, and the Australian Rotary Health Research Fund for their research grant funding.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.