INTRODUCTION

After World War II, the demand for equal remuneration emerged as a major item on the agendas of international organizations. In 1948, the United Nations (UN) adopted a resolution on “equal pay”. The International Labour Organization (ILO) followed in 1951 with the Equal Remuneration Convention (No. 100). With 171 ratifications, the principle of equal remuneration became truly global. Additional transnational agreements, such as the 1957 Treaty of Rome of the European Economic Community (EEC), have also played an important role. Since the UN's International Women's Decade (1976–1985), several international agreements concerning women's rights as human rights and agreements on international labour standards have included equal remuneration for men and women for work of equal value.

In general, the concept of equal remuneration has been successful in changing national legislation, but implementation has been less successful, so that even today women earn, on average, only fifty per cent of what men do.Footnote 1 In 1980, the International Textile, Garment and Leather Workers’ Federation (ITGLWF) published a short summary of a questionnaire concerned with equal remuneration in the textile industry. It showed that South Africa was the only country out of twenty-one where legislation was not applicable to all workers in the industry, even though the principle had been implemented.Footnote 2 At that time, South Africa was politically isolated, due to apartheid, and since 1964 it had no longer been a member of the ILO. In 1981, South Africa introduced its first equal pay legislation, which applied to the minimum wages of workers covered by industrial council agreements only. Not until 1984 was legislation introduced that set minimum wages for all workers. Since 1991, the Labour Relations Act and the Wage Act have protected against wage differentials for men and women doing the same job.Footnote 3

This article shows that the struggle for equal remuneration was embedded in the struggle against apartheid, through resistance against poverty wages.Footnote 4 Poverty wages were an important trigger of worker mobilization in most South African industries. Few countries have tried to structure income inequality as systematically and brutally as South Africa did under apartheid.Footnote 5 Apartheid politics affected incomes directly, as African and white workers doing the same work with the same qualifications were paid differently. Important elements of labour-market apartheid included the long-term exclusion of African workers from education and training, pass laws, forced removals, and the denial of access to certain job positions and to collective bargaining. From the 1970s, the labour market began to be de-racialized. This was the result of anti-apartheid protests in South Africa as well as of international monitoring. This shows the dialectical composition of the advantages and disadvantages of apartheid. Apartheid capitalism offered multinational companies an opportunity to produce at low cost in South Africa; at the same time, these multinational companies could become sites of resistance to apartheid due to their high visibility in the international context. Racial inequality was the result not only of public policies, but also of the interaction between these policies and capitalist development. It also intersected with gender relations, and African women were at the bottom of these hierarchies.Footnote 6

The struggle over poverty wages has traditionally been described as a struggle by male breadwinners, ignoring the role of women workers. However, oral history projects and contemporary reports speak to the fact that women workers in the textile industry were just as involved in these activities as men.Footnote 7 The struggle for wage equality between men and women has been overlooked and widely neglected in research too, despite the fact that it was on the agenda of South African women workers’ organizations as early as in the interwar period.Footnote 8 The demand for equal pay is mentioned sporadically in studies on women workers and trade unions. Research has also dated the struggle for equal remuneration to the end of the 1980s. For example, in his book Striking Back Jeremy Baskin claims that the National Union of Metal Workers of South Africa (NUMSA) spearheaded the campaign against wage inequality in 1988,Footnote 9 but activists were reporting at the beginning of the 1980s that equal remuneration for men and women had been an accepted negotiating practice in the Federation of South African Trade Unions (FOSATU) since its foundation in 1979.Footnote 10

This article is concerned with the struggle and negotiating practice of the National Union of Textile Workers (NUTW), a founding member of FOSATU, to implement equal remuneration in the South African textile industry between 1980 and 1987. It contributes to the history of South African women workers and their struggles to implement equal remuneration. It sheds light on the history of international solidarity with South African workers, by including the activism and demands of women workers, and it contributes to the debates on globally available concepts and the level of success in their implementation.

Between 1980 and 1987, before the NUTW merged into the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union of South Africa (ACTWUSA), the union handled fifteen cases of wage discrimination against women. In fourteen cases, initiated before the legal reform of 1984, the most blatant forms of wage discrimination were ended. The union had a predominantly female membership and a high record of industrial action over poverty wages and recognition agreements. I argue that we can explain the success of the NUTW with reference to its combined strategy of shop-floor activism and international coalition building, its ability to manoeuvre between and make use of domestic and foreign political opportunities, and its long-term strategy to make wage categories more transparent. This was partly possible because resistance to apartheid had mobilized workers, and their protests created new political opportunity structures. Apartheid capitalism attracted multinational companies with its low production costs based on poverty wages, but at the same time these multinational companies could be used as political opportunity structures and enabled unions to transfer international concepts to protect workers’ rights to the shop floor in South Africa. This improved wages for women workers in the textile industry, but, as elsewhere, the introduction of equal remuneration also cost women their jobs in some cases. The introduction of equal pay could give rise to recategorizations of jobs, where women again were in the lowest wage categories, and their work was often labelled “light” compared to the “heavy” work of men.Footnote 11

THEORETICAL MODEL

Social movement theory can explain why social mobilization processes take place and the mechanisms behind their success or failure. According to Charles Tilly, Doug McAdam, and Sidney Tarrow, mobilization processes depend on the creation and use of political opportunities, the use of specific repertoires of protest, and the process of interpreting and framing of grievances to convince the opponent. Political opportunities can emerge through increasing political pluralism, decline in repression, a division within elites, or political enfranchisement. To understand why mobilization for equal remuneration took place in the South African textile industry at this time and why it was successful, it is necessary to look at the new political opportunities that emerged and were created at the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s, both in and outside South Africa. As a result of reforms in labour relations and of both domestic and foreign pressure, apartheid was reformed; activists were able to use these reforms as a new political opportunity. The creation and use of political opportunity structures took place at different levels of scale, and it is therefore necessary to study the connections between them to explain the outcome.Footnote 12

During apartheid, women workers’ activism was predominantly situated at the shop-floor level, but grievances at multinational plants were sometimes sent on global or transnational journeys because resistance to apartheid had also created political opportunity structures outside South Africa. These international opportunity structures became available through international agreements signed by multinationals and could be used to create a connection between the plant level in South Africa and the plant level in the country of the company's main seat. Sidney Tarrow's concept of transnational activism is useful to focus on the mechanisms taking place in the triangular relationship of transnational activists, such as trade unions or the anti-apartheid movement, the state, and international institutions such as the ILO or the European Community, and explains why and how political opportunities emerging either nationally or internationally can be used in the mobilization process.Footnote 13 The use of the term transnational to highlight border-crossing activities is the result of debates about “methodological nationalism” and aims at going beyond the nation state. In recent years, this term has been criticised for a perspective stuck in a focus on the interaction among nations or between international organizations and nations. As part of a debate on global history and the epistemologies of global history, the local as space – for example in migration history – or the local as a site for micro-historical analysis has come into focus and the concept of translocal and translocality has been used to develop global history in a way that can include individuals in studies of larger, global, and universal processes.Footnote 14 As already mentioned, in FOSATU and its member organizations the power to negotiate and to resist lay at the level of the shop floor, and therefore action was initiated at the local level. It could lead to shared actions with others at the national and international level or with other workers at a specific factory abroad. To highlight this local initiative, I use the concept of translocal activism, meaning forms of mobilization for action where local action includes a link with other local activists abroad, and/or with activists at the international/transnational level, to connect their local workplace to other workplaces abroad, to states, and to international institutions.

I argue that part of the mobilization process depended on the local political opportunity structures created by the specific forms of exploitation on the shop floor in the South African textile industry under apartheid capitalism. Women workers mobilized locally for militant action, with numerous spontaneous strikes and protests. The outcome was highly dependent on the bargaining position of the union, the demonstration of its power, and its ability to change to a negotiation mode. As a reaction to mass protests and uprisings during the 1970s, the South African government, foreign governments, and international organizations introduced reforms and agreements to improve the situation of workers in South Africa. This created new domestic and foreign political opportunity structures for workers’ movements in South Africa. The recognition of non-racial unions is, without doubt, the most important achievement of the reforms and created new mobilization structures for workers. However, the global gender concepts embedded in these agreements, namely equal remuneration for men and women, have been overlooked by earlier research. The NUTW was able to translate and integrate global gender concepts in the framing of their local grievances and created one of the spaces that allowed the introduction of equal remuneration.Footnote 15 Multinational companies offered political opportunity structures, as they could be approached with reference to foreign legislation and agreements before South African legislation could be applied. After 1984, the union was more likely to refer to South African legislation. A comparison between the mobilization processes, domestic, foreign, and international political opportunity structures, and the mechanisms behind the translocal action versus national mobilization at two multinational plants, shows that the union used all available concepts and methods, combining translocal action with a legal strategy after the reform of equal pay legislation. In the last part of this article, I argue that the experiences of the equal pay cases led the NUTW to develop a national strategy for a more transparent wage structure, which contributed to advancing the struggle against multiple types of wage discrimination across the industry.

WOMEN'S ACTIVISM IN SOUTH AFRICAN WORKING-CLASS STRUGGLES

Despite coming from the same class, the experience of class differed between African female and male workers.Footnote 16 Apartheid also split groups of women workers. Job segregation resulted in different forms of discrimination and made it difficult to establish solidarity between groups of women. For example, coloured workers won trade union rights at the same time as white workers, before African women, which enabled them to reinforce job protection.Footnote 17

With a few exceptions, history has been concerned with the role of men in the mobilization of workers.Footnote 18 This is not peculiar to South Africa. The need to “gender” labour history has been discussed by feminist labour historians since the 1970s.Footnote 19 Feminist social scientists have criticised existing conceptions in political theory, as well as the analysis of politics and political actors, for excluding the activities and involvement of women in political organizations in general, and in trade unions specifically.Footnote 20 In the South African context, the colonial and apartheid construction of African women and their agency has contributed to their exclusion from analyses and conceptualizations of working-class struggles. African women were often described as docile and subordinate to men, in contrast to active male trade unionists taking part in the struggle.Footnote 21 The struggle over wages and working conditions has, according to Tshoaedi, often had a male bias, with frequent references to men being the breadwinner in the family, but interviews with women trade unionists have shown that these issues were as important in mobilizing women as they were for men.Footnote 22

Despite multiple intersecting forms of oppression, South African women have made significant contributions to workplace struggles as part of the formation of unions. Although women were important in mobilizing workers on the shop floor, they seldom became shop stewards or chairs of shop steward committees. They were often militant and dedicated members during strikes and demonstrations (Figure 1). For example, during the Durban strikes in 1973 a majority of the 100,000 participants were women.Footnote 23 Exposed to gender discrimination and sexual harassment by employers and male union comrades alike, women workers mobilized specifically for gender issues.Footnote 24 This has contributed to discussions about democracy and gender equality in the unions, including attitudes towards women in the unions, and put the demand for equal remuneration for men and women on the union agenda.Footnote 25

Figure 1. Women were important in mobilizing workers on the shop floor. Although they seldom became shop stewards, they were often militant and dedicated union members during strikes and demonstrations.

CATEGORICAL INEQUALITIES IN THE TEXTILE INDUSTRY

The poverty wages paid to the predominantly female African workforce in the textile industry were the reason why this sector had the second highest level of strike activity during the 1980s, after the metal industry.Footnote 26 Labour-market apartheid had been implemented in the textile industry as in other industries through job reservations for skilled white workers, and in the Western Cape through the Coloured Preferential Area Regulation. African workers held unskilled, low-paid jobs, their mobility was limited by pass laws, and they were excluded from collective bargaining.Footnote 27

After World War II, the textile and clothing industry was the fourth largest secondary-sector industry in South Africa. It was located in the Western Cape, the Free State, and Gauteng, and in cities like Cape Town, Durban, and Johannesburg, as well as in the reserves such as KwaZulu-Natal.

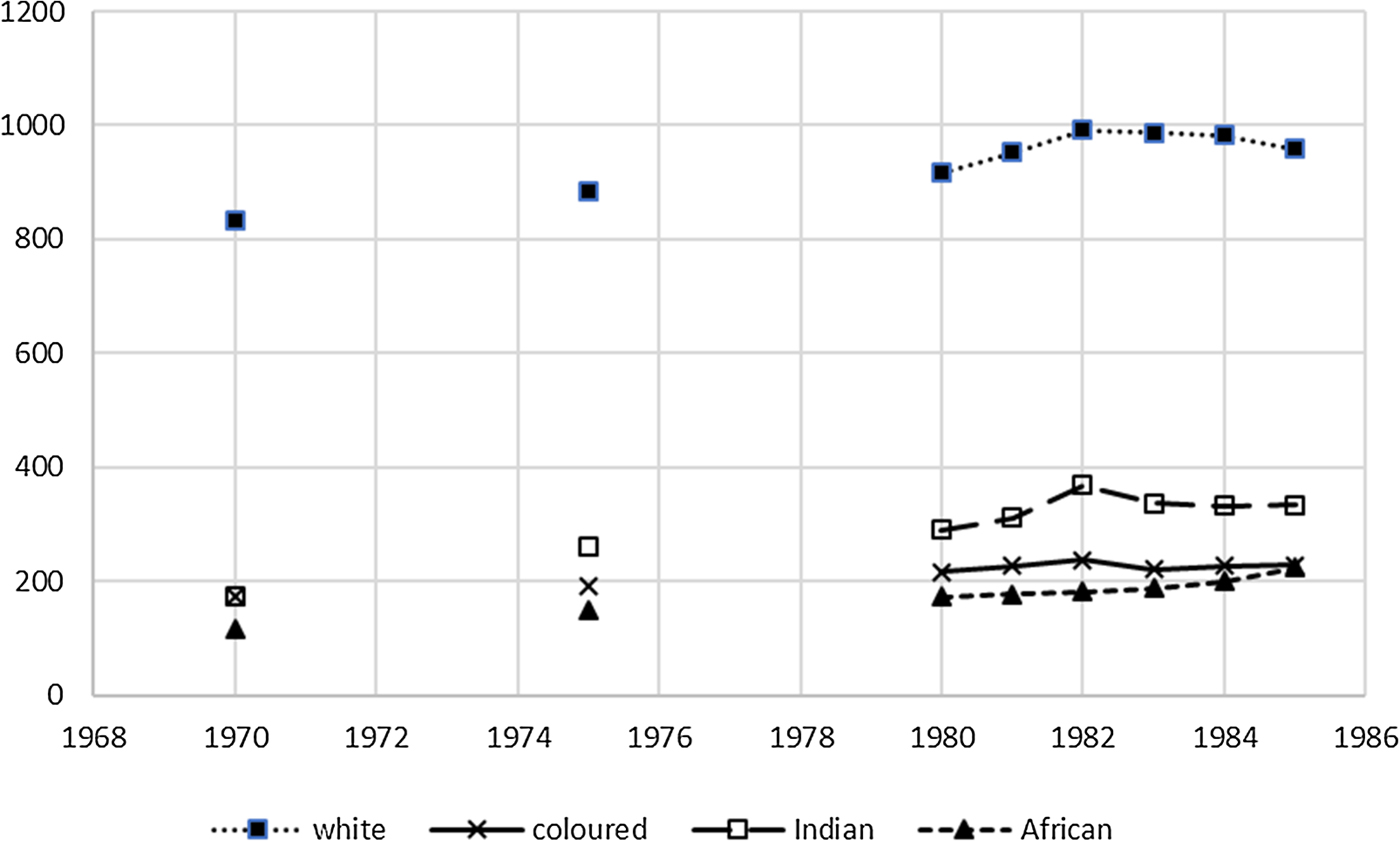

Official statistics on the workforce in the industry are not comparable over time. Some of the earlier censuses counted whites only and some excluded Africans. Moreover, racial definitions changed in the 1950s. Occupational and industry classifications were revised frequently, and gender was included only until 1960.Footnote 28 Despite inadequate statistics, we know from other sources that the composition of the workforce differed over time (see Figure 2). This was the result of the introduction of new technology in the 1960s, which increased demand for unskilled workers. Many jobs were downgraded and wages became very low. With this shift, African women moved into the industry and replaced white and coloured women, with a majority working as machine operators.Footnote 29 Since the 1970s, the proportions of different racial groups have been relatively stable, with only a small percentage of whites.Footnote 30 By 1980, about half of the workforce was female, with African women workers forming two thirds of the female workforce.Footnote 31

Figure 2. Size of workforce in the South African textile industry, 1955–1985, according to the racial categories of the apartheid regime.

From the 1960s, the industry needed large-scale investments for modernization. Production in South Africa was highly labour intensive and could survive only by producing import substitutes, protected by import tariffs and state subsidies for industries on the border of the reserves, the so-called homelands.Footnote 32 Between 1976 and 1981, only 1.9 per cent of production was exported.Footnote 33 The ownership structure in the industry during the 1970s and 1980s reflected the international relocation of the industry from northern Europe to southern Europe, Hungary, and the Global South. In South Africa, this had started in the 1930s, when British companies moved machines to South Africa. As a result, one third was owned by multinational companies, one third by the South African Frame Group, and one third by others.Footnote 34

Shifts between different racial groups and between male and female workers, as well as the relocation of production to the borderland areas, provided an opportunity for employers to downgrade and undervalue jobs, resulting in lower wage bills. South African decentralization policies offered cheap production in the reserves and on their borderlands. The idea was to attract European and Taiwanese companies to invest in labour-intensive industries on the border of the reserves, where about fifty-seven per cent of the female African population lived at the beginning of the 1980s. The largest investors were from the United Kingdom, Taiwan, and the US. The companies starting production in these areas were offered cheap labour, subsidized power, water and transport, tax concessions, cheap finance, subsidies, and exemptions from minimum wages. This was not enough to attract as many investors as envisaged, as the areas were simply too remote from markets to be attractive.Footnote 35 Nonetheless, textiles and clothing became the most prominent industries in these regions.

Most of the women in the reserves were excluded from work in urban areas due to pass laws and could find employment only in industries inside the reserves or on the borderland, where unskilled women were employed at extremely low wages.Footnote 36 In 1984, the NUTW reported that wages in Isithebe, part of KwaZulu, ranged between R14 and R22 per month, which was almost one third of the wages of a worker in Durban.Footnote 37 Wages were far below subsistence levels. During the first six month of 1984, a knitting-machine operator in Hammarsdale earned only 26.4 per cent of the recommended South African poverty level, as measured by the Household Effective Level (HEL), and only twenty-seven per cent of the recommended Supplemented Living Level (SLL). For a machine operator who had been working more than three and a half years, wages corresponded to forty-one per cent of the HEL and forty-two per cent of the SLL.Footnote 38

Like all other sectors and subsectors in manufacturing, official wage data for the textile industry for the period between 1970 and 1985 are highly inadequate. They show average wages only and do not include occupational wage rates (Figure 3).Footnote 39 We know that real wages all over the industry had been declining since the 1960s and had become an even more pressing issue after a rise in the cost of living at the turn of the 1980s. According to data from the NUTW published by the ITGLWF, real wages for a male knitting-machine operator decreased by more than 20 per cent between 1961 and 1983 (in 1975 prices) (from R26.21 to R17.58 per week). Due to the implementation of equal remuneration for men and women during the first half of the 1980s, wages for a female knitting-machine operator decreased only 12.8 per cent (from R20.16 to R17.58 per week) over the same period.Footnote 40

Figure 3. Monthly wages (in rand) in the South African textile industry at constant 1980 prices, according to racial categories of the apartheid regime

Although the data are highly inadequate, they show that by the mid-1980s income inequalities between blacks and whites had not changed in the textile industry. Additional, fragmentary data collected by unions and the ITGLWF indicate that wage gaps between men and women were introduced right from the start, when workers were first taken on. By 1984, after the implementation of equal remuneration, they had been closed, according to the data from the union. ITGLWF data on average weekly starting wages from 1977 showed that women earned 80 per cent (R18.90) of men's wages (R23.63).Footnote 41 Other examples show more blatant discrimination against women. Weekly wage data, including attendance bonuses, collected by the NUTW in January 1981 at SA Fabrics indicate (Table 1) that women were earning as little as fifty-one per cent (R30.90) of men's wages (R61.05).

Table 1. Wages in January 1981 at SA Fabrics (in ZAR).

* Plus one staff nurse.

Source: HP 2196 G 120.13, documents relating to arbitration.

A large unskilled workforce of predominantly African women, with wages far below the poverty line in the reserves; male-female wage differentials between twenty and sixty per cent; declining real wages since the 1960s; and a recent increase in the cost of living at the start of 1980 mobilized the textile workers to take militant action and triggered a range of spontaneous uprisings.

NEW POLITICAL OPPORTUNITIES

Protests against apartheid, such as the Durban strikes (1973), the uprisings in townships and especially in Soweto (1976), international pressure, and the decline in foreign investment, combined with an economic crisis, put pressure on the South African government and created new political opportunity structures. During the 1970s, governments in Western Europe and the United States were divided on the issue of sanctions as a way of ending apartheid. Some of these governments, the EEC, and some non-government organizations adopted so-called codes of conduct for multinational companies with subsidiaries in South Africa.Footnote 42 These agreements morally obliged multinational companies to implement the same working conditions in South Africa as at home. They were compromises between economic interests and moral obligations, legalizing the presence of foreign companies without sanctions. Companies had to draft reports to their national authorities, including information on wage levels, pay equity, and racial categories of employed workers.Footnote 43 The codes were welcomed by African workers as violations added to the high visibility of multinational companies and attracted the attention of international news media. They offered themes for contention and were used as checklists for unions during negotiations to remind companies of their moral obligations.Footnote 44

The South African government formed a commission under Professor Nicholas Everhardus Wiehahn to investigate possible reforms to South Africa's labour legislation.Footnote 45 Although aimed at reforming apartheid, these reports implied a nascent decline in apartheid and therefore opened up the possibility of new political opportunity structures in South Africa. The most prominent and important outcome was the recognition of non-racial unions, but less well known is the fact that both codes of conduct and the commission also pushed forward the global concept of equal remuneration for men and women. In the historiography on attempts to reform or end labour-market apartheid, the role of women has been entirely neglected, as has the role of these processes for women. I argue that the inclusion of global concepts of equal remuneration offered an international frame of reference that enabled African women in South Africa to put these demands on the agendas of trade unions.

All the codes urged South African subsidiaries of multinationals to pay fair wages, including equal remuneration for men and women. They also pushed for them to de-racialize facilities at work, to introduce equal and fair employment opportunities, to educate workers on an equal basis, and to promote African workers into managerial and other senior work categories. In addition, there were requirements to improve the quality of life for employees outside of their work environment, in areas of housing, education, and recreation. Further, the companies were urged to recognize non-racial trade unions and to reduce the hardships and inconveniences of migrant workers.Footnote 46 Equal remuneration for men and women added something specific to demands for decent wages. All codes demanded equal pay for equal and comparable work, with reference to ILO Convention No. 100 and Recommendation 111. The EEC Code of Conduct referred, in addition, to the Treaty of Rome and its narrower definition of equal remuneration as the same remuneration for the same work. It also included the demand that qualitative job evaluations be used as a strategy to implement equal remuneration. By 1985, all multinational companies excepting one British, Dutch, and German company had accepted the principle of equal pay with reference to the EEC Code of Conduct.Footnote 47

Equal remuneration was one of the few demands that did not conflict with racial segregation. The members of the Wiehahn Commission were suspicious of the different codes of conduct and condemned the negative attitude towards apartheid that permeated the codes of conduct.Footnote 48 The codes of conduct were a clear violation of the sovereignty of South African industrial relations, and these violations were criticized by representatives of the apartheid regime. Even though South Africa had withdrawn from the ILO in 1964, the members of the commission agreed that several ILO conventions were in accordance with South African labour legislation, but they could be accepted only if they did not interfere with the politics of apartheid.Footnote 49 ILO Convention No. 100 was one of the concepts that did not conflict with apartheid. The commission recommended that wage differences based on sex, age, or marital status should be outlawed, and that all laws contrary to the principle of equal treatment for men and women accepted by the 1935 Industrial Legislation Commission should be abolished.Footnote 50 With reference to a number of international codes, including ILO Convention No. 100 and Recommendation 111, the Commission on Transnational Corporations adopted by the UN ECOSOC, and the 1977 ILO Tripartite Declaration on Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy, the commission used international themes to frame the need to limit wage discrimination against women. However, compared to the intentions and the scope of the international concepts of equal remuneration, the introduction of the first equal pay legislation in South Africa in 1981 applied only to a limited number of women workers covered by industrial councils and only to minimum wages.Footnote 51

The codes of conduct, like the Wiehahn Commission, used global concepts to legitimise the introduction of equal remuneration, but because of their different, almost contradictory, attitudes towards foreign and international intervention, international themes played out differently. The codes of conduct were created with the intention of at least softening labour-market apartheid, even if not ending it. ILO Convention No. 100, as well as article 119 (now article 141) of the Treaty of Rome, referred to equal remuneration only in terms of gender and for that reason did not pose a threat to apartheid. The report of the commission and the codes of conduct brought these concepts to South Africa as a frame of reference, although South Africa was not a member of the organizations that had launched these concepts. The Wiehahn Commission used these concepts as part of its reform of apartheid, and although it formally rejected all international interference with the apartheid system the commission could not stop international interference at all multinational companies. This created two different political opportunity structures that were not available to all workers, for the codes of conduct applied only to workers at multinationals and until 1984 South African legislation covered only those workers under industrial councils. As the NUTW did not accept the industrial council system, this implied that the NUTW had good prospects of winning equal pay struggles only at multinationals, with reference to the codes of conduct.

NEW MOBILIZATION STRUCTURES

Without doubt, the Wiehahn Commission's recommendation that non-racial unions be recognized changed the mobilization structures for African workers by enabling the prospects of winning equal remuneration structures. According to Sakhela Buhlungu, black unions achieved the most decisive victories in their struggle for survival in the 1980s, because of the recognition of non-racial unions.Footnote 52 Spontaneous protests had characterized the non-racial labour movement since the 1960s, but the problem was to keep organizations sustainable over time, especially during the 1970s, when several leaders were imprisoned or banned. I argue that, in addition to these new mobilization structures, the specific repertoire of protest of the NUTW – a combination of shop-floor activism and international coalition building – enabled the union to create a stable mobilization structure that gave members on the shop floor negotiating power at their workplace and added international visibility that helped to put pressure on employers.

The NUTW was founded during the Durban strikes in 1973, but by the mid-1970s it had slowed down its activities because many of its leaders had been imprisoned or banned.Footnote 53 It was registered as a non-racial union in April 1981 and by 1983 it was among the largest and fastest-growing unions, with 20,000 members, a record of industrial action, and more than twenty recognition agreements. The NUTW was competing with several other unions, and during the early 1980s a bitter struggle between unions in the industry took place over possible new members and recognition agreements. But it worked together with the registered Textile Workers Industrial Union (TWIU), and for a time Johnny Copelyn was the secretary of both unions. This helped them in negotiations with the powerful Frame Group. By the end of the 1980s several mergers had taken place. In 1987, the NUTW merged with the ACTWUSA and in 1989 the ACTWUSA merged with the Garment and Allied Workers Union to form the South African Clothing and Textile Workers’ Union (SACTWU).Footnote 54

The NUTW was also a founding member of FOSATU, the strongest working-class organization fighting apartheid in the first half of the 1980s, with more than 140,000 members in 1985.Footnote 55 Between 1979 and 1985, FOSATU's affiliates focused on the local mobilization of workers under the political influence of “workerism”, which meant acting outside political parties. “Workerism” resulted in strong and autonomous industrial mobilization structures, with a distinctive bottom-up structure based on assemblies, shop steward committees, and representative bodies up to the leadership of the confederation. It mobilized large groups of women workers and involved them in the struggle.Footnote 56 “Workerism” was rooted in internationalism and local activism and heavily criticised by the banned “Charterist” South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU), which was allied with the ANC and the Freedom Charter. The NUTW's “workerism” was characterized by a plant-level bargaining strategy, which meant that decisions about wages were made locally at the factory. The NUTW created local political opportunity structures, sometimes using strikes and protests to get employers to the negotiating table. This was a protest against the industrial councils in South Africa, which were regarded as destructive of trade unionism and not representative of most workers.Footnote 57 The “workerism” of the NUTW brought together international and local political opportunity structures and, as early as the 1970s, enabled the union to create and use a translocal repertoire of protest. During these protests, local activists at a specific plant in South Africa and activists abroad, which could be either at the international level or at the mother plant of the company, put pressure on the multinational company. One of the first examples of this strategic approach was used in connection with the renegotiation of an earlier recognition agreement at a subsidiary of British Smith & Nephews outside Durban in 1977 (Figure 4). This was regarded as a turning point in union activism. After a boycott of the company's liaison committee and following contacts between the union in South Africa and the British union at the UK plant, the NUTW managed to use this connection to get publicity at home and abroad for the situation at the plant in South Africa, which put pressure on the company until the South African management gave in.Footnote 58 Using the union power of workers working for the same company but at a factory abroad enabled the NUTW to use this visibility abroad to force multinationals to ignore the pressure from the South African government. This strategy was used successfully in campaigns on a number of issues: in the struggle for recognition, against retrenchment, and for higher wages – including equal remuneration for men and women – despite the fact that international coalition building was a very complicated issue for the non-racial unions.Footnote 59

Figure 4. The NUTW used a translocal repertoire of protest and signed its first recognition agreement with Smith & Nephew, a British owned company, in 1974. NUTW representatives Johnny Copelyn (third from left) and Alec Erwin (second from left) signing an agreement with Dick Payne of the Tongaat Group covering union recognition at Hebox Textiles in 1982.

The relationship of the South African unions with the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) and the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) was problematic but offered resources. FOSATU did have active links with the ICFTU, mainly because this gave it access to the more powerful international trade secretariats (ITS) such as the International Metalworkers’ Federation and the ITGLWF.Footnote 60 At the beginning of the 1980s, the ITGLWF was probably the most experienced ITS when it came to multinationals, and it was the main partner for the NUTW.Footnote 61 The ICFTU and ITGLWF had access to information from management about the situation at different plants in South Africa and in the reserves that the NUTW had been denied.Footnote 62 The ITGLWF covered the costs of specific projects, of legal action, and the travel expenses of transnational activists who came to South Africa to support the NUTW. It was the money from the ITGLWF that linked the NUTW with the ICFTU. The ITGLWF was not as rich as other international trade secretariats, but it could apply for money from the ICFTU's fund earmarked for South Africa and use it for NUTW purposes.Footnote 63 In several of the equal pay cases, the NUTW built translocal coalitions between local activists and the international activists of the ITGLWF.

THE NUTW CASES OF WAGE DISCRIMINATION

During the 1980s, the NUTW had been successful in creating local opportunity structures. By 1983 it had recognition agreements with at least twenty factories before it merged with the ACTWUSA in 1987. For the period 1980 to 1987, I have found documentation on fifteen cases of wage discrimination against women in the industry. These are among the twenty-five cases relating to wages, wage discrimination, and the introduction of a new system for the categorization of jobs and wages. These cases are concerned with explicit wage discrimination in the form of different wage rates for men and women for the same job.

Table 2 gives an overview of the cases, the period of negotiation, and whether there was any translocal or international involvement, either through contacts or when international agreements or codes of conduct were used as a frame of reference. What do these cases tell us about the struggle for implementation? Not all the cases include enough information for a qualitative analysis, but a few include extensive documentation. In fourteen cases, the sources support the conclusion that the most blatant forms of formalized wage discrimination had ended by the second half of the 1980s; this confirms the NUTW wage data and the fact that most European companies subscribed to the principle of equal pay in accordance with the EEC Code of Conduct. Only in one case, Prilla Mills, was the outcome not documented. Here, wage discrimination was reported as late as 1986, and the reports ended with the breakdown of negotiations in the same year.Footnote 64

Table 2. NUTW cases of wage discrimination against women.

Source: AH 2196 G (factory cases).

A questionnaire published by the ITGLWF in 1980 showed that South Africa had implemented equal remuneration before legislation covered all workers in the textile industry.Footnote 65 The wage discrimination cases of the NUTW confirm that the struggle for equal remuneration took place and could be successful before legislation came into place. With one exception (Bonar Staflex), all cases of wage discrimination were taken up by the union before the new equal pay legislation came into effect in 1984; most but not all cases were settled before that date. Nine out of fourteen cases were settled before the legislation came into force, and five afterwards. In one case, Hebox Mills, the wage gap was closed in 1984, but the agreement to close the wage gap within the coming year had been made earlier, in 1983. This could be an indication for the effectiveness of the 1984 legislation in preventing wage discrimination.

There is some indication that the late implementation in the last five cases was due to a hostile attitude among the employers towards the union, which made negotiations difficult or even impossible and prolonged the struggle. In addition to Prilla Mills, mentioned earlier, the Frame factory was involved in twenty-five cases of legal action with the NUTW. The two multinationals, Moii River Textiles and Falke, were violating basic union rights, which was brought to the attention of the ITGLWF. As regards Bonar Staflex, the application to the industrial court was filed in December 1987, by which time the NUTW had already merged with ACTWUSA. This indicates that until 1984 the union had to use frames of reference other than national legislation to convince their opponents.

The cases also confirm that the NUTW systematically targeted multinationals. Among the fourteen successful cases there were, to my knowledge, at least five multinational companies and in all these cases the union either used its contacts with foreign unions, the ITGLWF, and foreign anti-apartheid organizations, or referred to the codes of conduct for companies with subsidiaries in South Africa.

In another five of the fourteen cases, the wage gap was closed through ordinary wage negotiations, before the legislation had come into effect. In these cases, wages were often equalized over a period of one or two years. Some of the minutes of these negotiations reveal that the discussions about equal pay were concluded with formulations such as “we all agree on the principle of equal pay”. This indicates that even though wage discrimination of women was still legal, there was a widely established acceptance of the principle of equal pay.

In an additional four cases it remains unclear if and how negotiations about wage discrimination against women took place. The records simply indicate that the wage differentials between men and women disappeared, but there are several possible explanations for this. Either the wage gap was closed, or men and women were no longer doing the same work, or their work was no longer categorized as the same work. A common way of keeping women's wages low, used across the world, was to move these women workers from gender-specific wage categories to the lowest paid categories in a new wage structure, often so-called light work categories, while men's work was categorized as heavy work.Footnote 66 Another recurring problem in the clothing and textile industry, especially in the South African-owned Frame Group, which also occurred in one of the NUTW cases, was that women were replaced by men or machines as soon as agreements about equal pay had been reached. Employers claimed that women workers were more expensive because of their sickness- and childcare-related absenteeism.Footnote 67

The fifteen cases indicate that wage equality was taken up before the legal reform. This could be an indication of the legal effects of the prevention of the most blatant forms of wage discrimination against women, or it could be an indication that the union had managed to end wage discrimination through systematic negotiations. Of approximately twenty companies with recognition agreements, fourteen discriminated against women workers. In only six cases did the union use a more militant repertoire of protest. This might have enabled the union to bring the partners to the negotiating table, but it required a shift to a less militant strategy during the bargaining process.

GLOBAL FRAMING OF LOCAL GRIEVANCES

As national legislation did not apply in the case of SA Fabrics and the plant was owned by a multinational company, the NUTW connected local political opportunity structures with international opportunity structures and framed their local grievances globally. Through international coalition building, the local grievances of the SA Fabrics workers were linked with the ITGLWF, which supported the case with money and by sending its general secretary Charles Ford to South Africa as a witness during the arbitration.Footnote 68 According to the former general secretary Johnny Copelyn, SA Fabrics was rather naive about this arbitration. The company had probably hoped it would not have to go to court and had not thought about how easy it would be for the various activists involved in the conflict to bring in support from outside South Africa.Footnote 69

Table 2 indicates an increase in cases where equal remuneration was implemented around 1983. A possible explanation for this could be what at first glance seemed to be a success in the first equal pay case at SA Fabrics. The case had received rather high visibility due to its format: it was the first private arbitration in South Africa, the ITGLWF introduced new principles in industrial relations, and an unfortunate outcome was that women workers lost their jobs after the equalization of wages. The case was used as an example in the education of women workers by FOSATU and the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU). It is likely that this case influenced the future strategy of the NUTW. In a letter to Charles Ford, the general secretary of the ITGLWF, Alec Erwin emphasized that it was “vitally important” to introduce the new principles Ford had used during the arbitration in industrial relations practice.Footnote 70 The case itself was rather typical for the situation in the textile industry at the beginning of the 1980s: 56 per cent of the workforce was African; 33 per cent Indian; 10 per cent white; and 1 per cent coloured. Wages were low, and because of the rise in the cost of living at the end of the 1970s real wages at the factory had declined by 11.3 per cent by the end of 1980. When workers discovered at the beginning of 1981 that the increase was 5 per cent instead of 12 per cent, a spontaneous strike broke out. This was a situation where the NUTW had to handle the spontaneous militancy typical for this period in order to ensure negotiations with the employers. The trade union leaders convinced the workers that bargaining would be more effective than continuing the strike, and as a result management agreed to a general wage increase to calm the situation. The union had agreed to deal with details of the increase for each wage category later.Footnote 71 One of the issues was the discrimination against women workers. Basic wages, attendance bonuses, and family allowances paid to women were all lower than those paid to men doing the same or similar work. Management suggested private arbitration, which resulted in a 12.5 per cent increase and three months’ backpay, with an agreement to equalize basic wages for men and women by July 1982.Footnote 72 But shortly after this, the company started making workers redundant. It is likely that most of the women lost their jobs due to the equal pay case.Footnote 73 According to SA Fabrics, women were more difficult to place in shift work as they needed exemptions from the Factory Act. Women were regarded as less useful as employees because of their liability to take maternity leave, and finally, the employer argued, women were not the breadwinners in a household and were therefore not entitled to the full marriage allowances, which varied with the number of children.Footnote 74 Women had recently been employed to replace men for as little as fifty-one per cent of male wage rate for the same job (Table 1). At this time, the NUTW had no retrenchment agreement with the company, and even using the “last in, first out” principle would have cost the women their jobs.Footnote 75 Before the redundancies, the company had employed 596 men and thirty-seven women (Table 1).

Ford, representing the ITGLWF but also an experienced trade unionist from the UK, reminded the owners about their obligations to British equal pay legislation, the equal pay paragraph of the Treaty of Rome, and paragraph 21 of the ILO's Tripartite Declaration on Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy about the elimination of all discrimination, inter alia that based on sex. And he underlined that this agreement was acknowledged by multinational companies. But a moral reminder to management would have an effect only if management were ready to negotiate with the union.Footnote 76 To bring them to the bargaining table after a strike required management to have a certain degree of trust in the union. Copelyn navigated skilfully between showing that the leaders of the union were in control of the workers and putting pressure on the management. Similarly, as Ford had done when comparing the situation at the UK plant with the South African plant, Copelyn compared the wages at SA Fabrics with the company that paid the lowest wages in the industry, to show that starting rates at SA Fabrics were even lower.Footnote 77 Ford also invited negotiations; he showed an understanding of the specific situation for multinational companies when operating in developing countries where comparable employers did not exist, but he recommended that the workers be treated as fairly as the political system allowed. To mitigate the conflict, Ford described the process of ending wage discrimination against women, again with examples from Europe, as an almost evolutionary process. He pointed to EEC directives as an example of how to remove discrimination in job classification systems.Footnote 78

The South African case also illustrates how border-crossing activism needed to navigate between local militancy and international “labour diplomacy”. The activists played different roles: the NUTW representatives framed their arguments with reference to the South African situation, and Ford acted as an expert on equal pay legislation in Europe and managed to shift the topic in a way that displayed British legislation as the most relevant at the plant in South Africa. Although the ITGLWF was involved in several of the cases, to my knowledge this was the only case where an ITGLWF representative was personally involved on the shop floor in South Africa.

TRANSLOCAL ACTION

The second case concerns Falke Textiles and follows a pattern of local grievances and militant action at the local level similar to that seen in the first case. The Falke case is typical for the other NUTW cases in that it took much longer for the union to be recognized, and so longer to establish local opportunity structures, and this prolonged the outcome of the negotiations. It differs from SA Fabrics in the interaction between local, national, and international opportunity structures. First, the reform of South African legislation in 1984 made it applicable to the plant. Secondly, international coalitions with the ITGLWF were not as important as in the SA Fabrics case. Despite the attempt of the ITGLWF to connect the NUTW with the German textile and clothing workers’ union, Gewerkschaft Textil und Bekleidung (GTB), this did not result in effective coalition building between the unions. Instead, the structure of action built mainly on a coalition with local West German anti-apartheid groups, which managed to activate other anti-apartheid groups and a well-known social democratic politician, who put pressure on the German management. In the Falke case action was used to create visibility in West Germany. This opened up an opportunity in the negotiations to raise the question of equal remuneration.

Falke was a subsidiary of the German company Falke, located in Bellville near Cape Town. In January 1983, about 150 African and coloured workers were employed at the plant, but unfortunately the sources do not include any information about the numbers of men and women.Footnote 79 The two major problems were recognition of the union and excessively low wages, including wage discrimination against female workers. Conflicts, including strikes and legal procedures, are documented as occurring between 1983 and 1987.Footnote 80 The workers had contacted the NUTW in January 1983 for support; Falke responded with extreme hostility and the situation escalated into strikes.Footnote 81 Solving this difficult situation so that negotiations could begin was vital for the struggle against poverty wages and wage discrimination against women. Negotiations resumed in the second half of 1984, when management made its first proposal to increase wages, which included differentiated minimum wages for men and women.Footnote 82 The union representative for the Western Cape Branch, Virginia Engel, rejected this proposal with reference to the South African legislation and the results of the Wiehahn Commission.Footnote 83 In January 1985, management presented a new proposal for a general increase of twelve per cent for all employees, but the proposal still included a difference in the minimum wage for men and for women. The NUTW refused to sign an agreement that included discrimination against women workers and referred once more to South African legislation. By February 1985, the Falke management had promised to make a clear commitment to equalizing wages between men and women. The final agreement, including equalized wages, was signed at some point during the end of February or the beginning of March 1985.Footnote 84

This case confirms the thesis that the legal reform of 1984 made it easier to frame local grievances with reference to South African legislation, which means connecting it to national opportunity structures. However, the problem of denied negotiations remained an obstacle to the negotiation of equal remuneration for men and women. What were the processes and mechanisms behind the success of this case?

First, the Falke case shows that the local internalization of international agreements, in this case the EEC Code of Conduct, needed international visibility. In other words, it required a shift in claims from the shop floor in South Africa to West Germany. The minutes of the local negotiating committee do not indicate that this happened during negotiations in Bellville. The EEC Code of Conduct was not referred to explicitly, but its principles were part of the union's demands. The union demanded job descriptions and job evaluations, and access to the statistics on number of workers and wages, as stipulated in the EEC Code of Conduct. The reports to the German Gewerkschaft Textil und Bekleidung and to the ITGLWF included explicit references to the EEC Code of Conduct.Footnote 85 Second, the NUTW had difficulties building coalitions with the German union. Without coalitions, it was almost impossible to bring the German union on board in the struggle and to support the claims of the South African workers. The NUTW had contacted the local branch of the GTB twice and asked explicitly for support in the struggle for recognition and decent wages, referring to the EEC Code of Conduct, but without success.Footnote 86 The ITGLWF offered a space for international coalition building and the NUTW used the meetings of the ITGLWF in Tel Aviv in October 1984 and in Tunis in January 1985 to speak directly to the president of the GTB, Berthold Keller, who promised to support the case and contacted Falke's management in Germany.Footnote 87 But this resulted in a difficult situation, for it placed the Falke management's word against the NUTW's word. Falke rejected all accusations by the NUTW and informed the German union that all problems had been resolved by the recognition agreement.Footnote 88 This must have disarmed the arguments of the German union. The contact between the NUTW and the GBT on this matter seems to have ended here.

Instead, the NUTW got in touch with a German organization involved in the anti-apartheid struggle, namely the South Africa Scholarship Fund e.V. in Tübingen (SASF). The contacts were the result of networks between church organizations in Germany, namely the Kirchlicher Dienst in der Arbeitswelt (KDA), and South Africa.Footnote 89 The correspondence between the NUTW and these organizations indicates a shift to activism in Germany, which increased pressure on the South African management. In January 1985, the SASF published a report on the situation at Falke in its quarterly magazine, which added to the visibility of the case in Germany.Footnote 90 Robert Kriger of the SASF, originally from the Western Cape and a friend of Virginia Engel, wrote to her: “We felt that most German firms only react when some form of negative publicity regarding their overseas subsidiaries (esp. SA) is distributed here.”Footnote 91 This strategy was successful. Kriger offered Engel to help build coalitions between the German and the South African workers and to put pressure on both the management and the German union. According to Kriger, Falke and the GTB were “bombarded with hundreds of letters and petitions”; the German-speaking women's organization Frauen für Südafrika, with members in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, threatened to put Falke products on their boycott list.Footnote 92 Heide Simonis, a member of the German parliament who visited the plant in South Africa at the suggestion of the SASF, confronted Falke's management in Germany and lambasted the GTB for its inaction in the matter.Footnote 93 The SASF contacted the manager at Falke's German headquarters, Franz-Otto Falke, who responded only after the agreement had been reached in March 1985, to say that the demands had been met by the management, a formal recognition agreement had been signed, and “a positive, formal working relationship” had been established between management and the union.Footnote 94

The lack of sources from the Falke management makes it difficult to prove the direct influence of the activity in Germany on the decision of the Falke management to finally sign a wage agreement. But the visibility initiated through the activities of the SASF makes it very likely that the pressure on the German management opened opportunity space in Bellville and enabled local activists to include the demand for equal remuneration in this space. Coalition building with unions in Germany proved more difficult, but this was compensated for by the networks of churches that could reach both workers and organizations at the local level. In addition, as in the SA Fabrics case, international coalition building included access to monetary resources: the SASF donated almost R2,000 to the Western Cape branch, and more money was to come.

NATIONAL REPERCUSSIONS OF LOCAL STRUGGLES

There are reasons to believe that the legal reforms in 1984 ended the most blatant forms of wage discrimination in the textile industry, but the wage differentials between workers in rural and urban areas remained a challenge. In some of the equal remuneration cases, employers reacted to the equalization of wages by changing existing wage categories and by moving women into “light industrial work categories” and men into “heavy industrial wage categories” to justify lower wages for women. This form of wage discrimination was more difficult to detect compared with separate wage categories for men and women with different rates.Footnote 95 Charles Tilly has described job categories, the demarcation of jobs, the ranking of jobs, power over categorical differentials, and the recruitment of new employees as “organizational junctions” that generate inequality.Footnote 96 The NUTW started to handle this problem systematically around the mid-1980s, when membership was growing and it became relevant to develop a strategy for the entire industry. The strategy was the result of experiences from wage negotiations in general and, as I argue, the recommendations to implement equal remuneration specifically. This was a shift from a local to a national strategy, which grew out of the necessity to gain access to wage data at the plant level.

Wage statistics constitute an important power resource, available almost exclusively to employers. The unions’ lack of access to them gave employers an advantage during negotiations. From the 1960s, international bodies such as the ICFTU, the ILO, and the EEC recommended mapping wages and wage categories by means of job descriptions and job evaluations.Footnote 97 Ford had referred to this in his statement during the arbitration, and the NUTW had requested details of pay rates or job categories with reference to the EEC Code of Conduct after Falke's management had denied them this information for months.Footnote 98 This was not a problem specific to the Falke plant – it was widespread in the textile industry and a general problem in South Africa.Footnote 99

Some activists saw the job evaluation system as a tool of employers, but others saw it as a chance for workers to influence the design and content of these categories.Footnote 100 The NUTW worked systematically to influence the design. In most of the twenty-five NUTW cases concerned with wage negotiations, the files include wage slips from workers; these were used to assemble existing wage categories and wage data. But it turned out to be difficult to compare the available data and therefore, in agreement with the employers, the union tried to change the grading system.Footnote 101 In some cases the NUTW had to renegotiate existing job-grading systems and make them fit into the NUTW system. The most common job evaluation system in South Africa was the Paterson system, which based the grading of jobs purely on the level of decision making that was part of the job. This resulted in six bands, where manual workers were placed in the lowest bands. These bands were then subdivided into more categories. In most cases management introduced the system without any union influence. Although it was declared to be a means to describe the job content only, the evaluation structure also determined the wage structure.Footnote 102 The results of these changes of categories enabled the NUTW to gain a more systematic overview of wage categories, job descriptions, and job evaluations across the textile industry. This system made it more likely that latent wage discrimination against women could be detected, and it helped to demonstrate the wage inequalities between plants in and outside the reserves.Footnote 103

The collection of data and the introduction of a low-scale job-grading system had a second purpose: to keep the number of divisions between workers as low as possible. A high number of different wage categories indicates a substantial division of workers that can be used to create wage differentials. Detailed categories are helpful in mapping inequalities because they add to the visibility of inequality, but to end categorical inequality it is important to keep the number of categories low. The NUTW introduced a system that consisted of a maximum of five job grades across the whole textile industry.Footnote 104 This was an effective way to abolish the ninety or even more wage-grading-category systems, including gendered wage categories.

Internalized from foreign and international agreements and recommendations at the local level, the NUTW developed a national strategy that advanced the struggle against labour-market apartheid by adding visibility to different types of wage inequality and by aiming to minimize the division of workers for general wage justice. This shift towards a more technocratic and academic approach enabled the NUTW to make the wage structure more transparent. It reduced the number of divisions in categories of work and thereby also among groups of workers in rural and urban areas. This still left open the possibility of biased categories, but having fewer categories meant they were easier to compare and made it easier to detect inequalities.

CONCLUSION

The concept of equal remuneration has been successful in changing national legislation worldwide, but there has been less success in implementing the necessary legislation on a global scale. In South Africa's textile industry, implementation predated legislation during the 1980s. The resistance to apartheid and the embedded struggles against higher wages created political opportunity structures at different levels of scale and enabled the NUTW to systematically and successfully demand equal remuneration before legislation came into place and before COSATU and NUMSA launched their major campaigns in the second half of the 1980s.

To compensate for the lack of adequate national legislation covering all workers, union activists in South Africa connected local opportunity structures with foreign and international opportunity structures until national legislation changed and became applicable to all workers. South Africa had attracted multinational companies owing to its low production costs as a result of labour-market apartheid. At the same time, due to the international monitoring of the apartheid regime, these companies were often bound to national and international agreements that obliged them to treat their workers in South Africa in the same way as at home.

The struggle against apartheid had mobilized a large militant female workforce in the textile industry which stood behind the systematic elimination of the most blatant forms of wage discrimination against women in the industry. They had mobilized workers to fight for local political opportunity structures in the form of recognition agreements between employers and the NUTW. Through a connection of local opportunity structures with foreign or international opportunity structures, it became possible to refer to legislation in the company's country of origin and to the international agreements signed by the country of origin. South African activists depended therefore on international coalition building, and sometimes activism needed to be shifted from the shop floor in South Africa to other countries. International and transnational coalition building made foreign and international concepts of equal remuneration available to women-worker activists on the shop floor of multinational plants in South Africa, before legislation became applicable to a larger proportion of workers in other plants as well. However, without the local activism of the union in South Africa these concepts remained toothless. South African workers had to initiate the connections either through representatives of international trade secretariats or through union activists either in the company's country of origin or by local activists at the mother plant of the transnational activists. These connections illustrate at the same time the limitations of translocal action. Pressure on foreign companies was most effectively applied by foreign activists on their employers at home not to follow South African legislation. Once South African equal pay legislation covered all workers, the union turned to national opportunity structures instead and referred directly to South African legislation.

When unions started to analyse the more hidden forms of wage discrimination against women, they used new methods of mapping wage equalities recommended for the elimination of gendered wage gaps. And although these methods did have their problems, they have contributed to the transparency of wage structures and to advancing the struggle for wage equity in general across the entire industry. This implies that the struggle among women workers advanced the situation of all workers. It is therefore important to look at different levels of scale and at the connections and entanglements between them in order to make women's activism visible, and this invites us to study the impact of their activism on the situation of all workers.