Introduction

In a 1994 Guardian article entitled “Lie Back and Think of Efficiency,” then Labour MP for Dulwich Tessa Jowell quoted a letter she had received from one of her constituents, a London hospital consultant. He wrote, “[t]here have been two patients waiting in the casualty since Monday afternoon, that is for 40 hours, waiting for beds to become free in the hospital.”Footnote 1 In response, she visited five of the major casualty departments in London, none of which apparently had any beds available. At one site, an unconscious man was cared for on a mattress on the floor. Jowell leveraged this description of sick people “suffering private pain so publicly” into an attack on her political rivals, calling it a “calculated result of Government policy.” She also contrasted it with the “old days,” when there were more beds—some of which were even empty—and people were not “stacked in hospital corridors.”Footnote 2 Quantity of, and access to, hospital beds was, according to Jowell, a measure of NHS quality and a metric of good care. In her narrative, the bed became a political tool, one easily wielded against political foes, and a cipher for crisis and decay in the health service. This identity, however, had only emerged over time. Indeed, throughout the lifespan of the NHS and before, the hospital bed has meant many things. At various points, it has been made into a symbol of homeliness, hygiene, high technology, efficiency, standardization, inequality, abuse, and crisis.

These various meanings have been layered, co-existing rather than replacing one another, being deployed by different parties, for different ends.Footnote 3 As historian Rob Boddice says about objects, “[t]here is nothing intrinsically meaningful in any object, but the way in which an object is constructed in a space, placed into a narrative, associated with something beyond itself, and with past experiences, all endow said object with meaning.”Footnote 4 In this article, we interrogate this process of meaning-making for the NHS hospital bed. We argue that the hospital bed was always more than just a piece of furniture; it existed conceptually, and materially, in relation to a range of people, objects, social relations, political contexts, and more.Footnote 5 To do so, we make a distinction between the numerical bed, which is something of a political and media abstraction, and the material bed as object. These are only two of the many competing notions of what the bed is and ought to be. Yet, today, it is only the numerical bed—“how many beds do we have?”—that receives any kind of prominent coverage in political discourse or in the mainstream press.

This popular focus on the numerical bed is a relatively recent phenomenon. In broad terms, this article supports scholarship that shows that there was a politicization of the NHS in the 1970s.Footnote 6 Examining this politicization via the hospital bed also supports and advances scholarship that shows “crisis” and “decline” to be constructions.Footnote 7 This is not to claim that there were not genuine problems in the NHS at this time, but rather to argue that the language of “crisis” was often a choice that served particular political or rhetorical functions. There was an alternative narrative available, in which the bed is examined as a material object, in which declining bed numbers meant more efficient healthcare, greater comfort, or qualitative improvements in care. In showing these alternative narratives, this article aligns with and significantly advances a new trend in NHS historiography that goes beyond politics, economics, and even health to understand the place—and nature—of the NHS as a cultural construction.Footnote 8 These two intersecting—but distinct—bed stories show, to quote Sally Sheard, the value of “understanding the NHS as not a monolith but as a composite of hundreds of diverse parts.”Footnote 9 Different versions of the hospital bed bring some of these “diverse parts” firmly into view for the first time.

There are no existing material or political histories of the NHS bed. This is perhaps surprising considering its ubiquity, both as an object in the hospital and as a trope of political and media rhetoric. There is extensive, excellent historiography and interdisciplinary scholarship on the hospital bed or the sickbed as objects in other contexts.Footnote 10 Some of this work focuses on the bed as a material, sensory, and emotional object, while other work emphasizes changes to bed design or the meaning of beds. None of it, though, has yet considered hospital beds in relation to the NHS, nor put the material history of the bed as object in dialogue with the bed as political and economic symbol. Political and economic histories of the NHS are also commonplace, but they, in turn, tend to function at a “meta” level.Footnote 11 This article therefore offers new ways of thinking about hospital beds, as well as histories of the NHS, and its multiple meanings and multiple chronologies, in modern British history. For scholars of other places and subjects, this article also shows the value of starting with a narrow focal point that cuts across other approaches to history, rather than starting with a focus on, for example, material, political, or social history. Only by putting stories in dialogue is it possible to unpick the differences between them.

The Numerical Bed

Concerns about hospital bed shortages were present throughout the NHS's lifetime as part of ongoing anxieties over its health, resourcing, and resilience, but comments about bed shortages became increasingly prevalent and increasingly politicized as the service aged. This trend was apparent in health service policymaking, in the political manifestos of the period, and in the press. This first section of this article considers the history of NHS bed policy, and how this compares with discussions of bed numbers in political debate, manifestos, and the media. It shows that there was something of a disjuncture between the goals of policymaking, in which the decline or redistribution of hospital beds was part of making hospitals more streamlined and efficient, and other public discussions of bed numbers as a symbol of the NHS in “crisis.” Despite efforts to disentangle “good care” and “lots of beds,” particularly by Enoch Powell in the health service's early years, the two concepts were closely entwined in culture and politics. Furthermore, now newly reframed as a node in a system, the “bed” increasingly became a symbol of bottlenecks and inefficiency as concerns grew about the “blocking” of pathways to recovery. The absence of beds was thus a marker both of a perceived lack of investment in hospitals, drawing on long-held ideas about the bed as a symbol of care, and of the shortcomings of the new NHS as a streamlined, productive, or modern system. We offer, in this section, a case study to support the idea that the NHS “crisis” was always in part a constructed one, and show that the hospital bed was a particularly powerful tool for those who sought to escalate this notion.

In broad terms, the second half of the twentieth century was a period of falling bed numbers. The free-at-the-point-of-treatment service introduced in 1948 meant that healthcare was more accessible to a larger proportion of the population than ever before. On 5 July 1948, the NHS in England and Wales absorbed 1,143 voluntary hospitals with some 90,000 beds, and 1,545 municipal hospitals with about 390,000 beds (including 190,000 in psychiatric institutions and hospitals for people with intellectual disabilities).Footnote 12 There was some limited expansion of bed numbers, with 418,000 occupied beds in England and Wales by 1958, but the numbers soon dropped again, with a steady decline from around 1960 that continued throughout the rest of the century and beyond.Footnote 13 As Geoffrey Rivett notes, between 1969 and 1978, there was a 15 percent reduction in the total number of medical beds in the NHS.Footnote 14 A report published by The King's Fund in 2021 found that the total number of NHS hospital beds in England had more than halved over the preceding 30 years, from around 299,000 in 1987/88 to 141,000 in 2019/20.Footnote 15 This general picture of overall bed decline over the course of the later decades of the twentieth century of course obscures substantial variation according to place, specialty, and type of institution. The number of beds dedicated to respiratory diseases halved, whereas cardiological beds increased by 50 percent.Footnote 16 Infectious disease and general surgical beds also closed, due to the increased use of antibiotics. In maternity care, home deliveries were declining and by 1968, 80 percent of women were giving birth in hospital, so the number of maternity beds rose correspondingly.Footnote 17 In contrast, beds for the inpatient care of people with mental illness dropped from 157,427 in 1954 to 133,667 in 1969.Footnote 18 Even with these variations in mind, the decline in bed numbers is a useful overall starting point for understanding public concern about the issue, particularly as the nuances of different specialties were also often lost in public discourse.

In the early years of the NHS, there was already some concern about the capacity of the new system, particularly in the face of a largely absent hospital-building program. In 1949, doctor and Liberal politician Sir Henry Morris Jones claimed that before the Health Service Act had come into force, “no hospital in London or elsewhere refused emergency sick cases.”Footnote 19 He berated Aneurin Bevan, the Minister of Health, insisting that “[m]edical men had to be on the telephone for over an hour every day trying to get sick people into hospital.” The British Medical Journal (BMJ) confirmed his claims, writing that the “difficulty of getting acute cases into hospital is being experienced by practitioners throughout the country.”Footnote 20 Reports about bed shortages can also be found dotted through the tabloids right from the health service's inception. A Daily Mirror article from 23 December 1948, for example, declared “Doctor Sent Dying Woman Home: No Bed.”Footnote 21 At this time, such articles were relatively unusual, but—alongside the political and medical discussions of bed numbers—they served to connect hospital bed numbers to the problem of scarcity in the context of a system that was supposed to serve the entire population.

In 1962, the Conservative Minister of Health Enoch Powell published the Hospital Plan for England and Wales. Significantly, and perhaps surprisingly, this plan did not seek to increase bed numbers.Footnote 22 It intended to produce a network of district general hospitals with 600–800 beds, but aimed specifically for better distribution of beds and their more efficient use, with an overall decline in NHS bed numbers. As Alistair Fair has shown, the Hospital Plan was just one of several “modernizing plans,” including the Robbins Report on higher education (1963), the Buchanan Report on traffic planning (1963), and the Parker Morris report on the design of housing (1961). The Hospital Plan also embedded a prevailing commitment to design standardization, an ideal also present in other examples of public architecture like schools and social housing.Footnote 23 Rational planning was, therefore, the key ideology sustaining Powell's plan, not just a straightforward expansion of the hospital service.

As the number of beds declined and media attention to bed numbers grew, there was very little public recognition that fewer beds were something that policymakers might choose in pursuit of a more efficient system. Instead, from very early on, a lack of beds was wielded as evidence of scarcity and a lack of investment. This rhetoric was encouraged by politicians across the political spectrum, who recognized—and in so doing reinforced—the symbolic importance of beds to citizens. In 1965, the Daily Mirror reported, under the heading “LACK OF BEDS COSTS LIVES—MP,” that the “Tory MP” for Arundel and Shoreham had said that, “people are dying unnecessarily because of the shortage of hospital beds.”Footnote 24 In 1966, the same newspaper reported that the Labour Health Minister had declared “there should be 1,500 more hospital beds for mothers-to-be by the end of next year.”Footnote 25 By the mid-1960s MPs and many Ministers from across the political spectrum emphasized in public statements that investment in hospital beds—or at least hospital beds for certain types of patient or service user—was important. This was also evident in the decade's political manifestos. The Labour Health Minister's emphasis on maternity beds had actually been pre-empted in the Conservative Party Manifesto in 1964: “priority will be given to additional maternity beds, so that every mother who needs to will be able to have her baby in hospital.”Footnote 26

While this kind of rhetoric was present in the 1960s, it was relatively sporadic and muted. In the 1970s, media coverage of hospital bed numbers underwent a significant tonal shift. The shortage of hospital beds became a repeated topic of parliamentary debate, a trope of media coverage, and tabloids adopted increasingly dramatic language, like “crisis” and “axing.” In July 1979, for example, the Sunday Mirror published an article with the large, capitalized headline: “HOSPITALS AT CRISIS POINT: Jobs and beds to go in cash curbs.” The article noted that, due to a funding shortfall, staff and “many” hospital beds were due to be “axed” in a “huge new crisis” for the health service.Footnote 27 Similar concerns were articulated across the political spectrum of the British media. On 12 February 1981, the Daily Mail published an article with the heading “Facing the axe … 4,000 hospital beds.”Footnote 28 This article was reporting on a specific policy announcement from the Health Minister in relation to cuts in London, the South East, and the Home Counties.

These changing meanings of the hospital bed took place in the context of what Sally Sheard identifies as an increasing politicization of the health service, a process that began in the 1970s and continued through the 1980s and beyond.Footnote 29 The hospital also became increasingly visible in homes from this period: on television, in books, and in the press.Footnote 30 It was at this time that new and very public anxieties emerged about the quantity of hospital beds, their distribution, occupancy, and efficiency. Further, it was then that debates about beds became proxies not just for what constituted good, “modern” healthcare, but for the state, resilience, and resourcing of the NHS.

This media rhetoric of “crisis” and growing attention to bed numbers in political manifestos did not seem to acknowledge that declining bed numbers were the result of a deliberate policy decision. The only way in which this goal of redistribution and efficiency had an impact on political and media discussions of the bed “crisis” was in relation to the apparent problem of “bed-blocking.” This was a product of the idea of fewer beds as a marker of efficiency: the bed was a node in a system, or part of a flow chart, and fewer bed numbers only worked as an efficiency measure if the system flowed freely. Even though people generally were spending less time in hospital and flowing through the system more rapidly, the idea of “bed-blocking” took hold at this time. The phrase was first used in parliamentary debates in the late 1970s but was taken up with enthusiasm by the media in the 1980s and 1990s. In 1978, the Labour MP and Under-Secretary of State for Health and Social Security Eric Deakins drew attention to the fact that the “elderly are major consumers of the services of the acute specialities.” He highlighted the plight of Bournemouth, with its “heavy concentration of elderly residents,” and the widespread “deficiencies in provision of geriatric services and of services for the elderly severely mentally infirm.” Together, this had resulted in “substantial ‘bed-blocking,’” which was a “major contributory factor to the district's long waiting lists for various forms of surgery.”Footnote 31 The problem was not, then, that there were not enough beds, but rather that they were being used in inefficient ways. It is significant, however, that the focus on these conversations stayed on the bed. The headline term “bed-blocking” again implied that bed numbers were the key problem, even when on closer examination much of the criticism was actually about shortages in social care provision. The bed was a powerful, catch-all symbol of NHS “crisis.”

This numerical, crisis-stricken version of the hospital bed also rarely considered other statistics that made sense of declining bed numbers, such as duration of stay or geographical distribution of beds. For example, as the number of hospital beds fell, so did length of stay, and the numbers of patients passing through hospitals increased. Rivett notes that, while numbers of medical beds dropped between 1969 and 1978, the average length of hospital stay also fell from 16 to 11 days. For surgical patients, the figure declined from 9.7 to 8.2 days, and 22 percent more medical patients and 10 percent more surgical patients were being discharged.Footnote 32 As noted above, there was also an increase in maternity beds, at the same time as those for long-stay older patients or mental health patients were cut. There was an effort to reduce bed surpluses in London in favor of more equitable access. Questions of equity and the redistribution of hospital beds were also central to attempts by Labour's Minister of Health and Social Care Barbara Castle to abolish the “pay beds” that allowed consultants to do private work in NHS hospitals.Footnote 33 In the 1970s, then, the policy around NHS beds was primarily one of redistribution, which meant a reduction where beds were perceived as unnecessary but an increase where there were shortages.

Much of this nuance was lost in the coverage provided by tabloid newspapers, which were very specific modes of communication that tended to simplify the question of NHS bed numbers. Elsewhere at this time, efforts were made to distinguish between the bed as a site of care and anxiety about bed numbers as a way of accessing that care. One local hospital gazette, ironically, considering the growing furor around bed number shortages in the national media, ran a story in March 1975 entitled “Can we staff these empty beds?,” emphasizing that bed numbers could not be assessed without appreciating the wider context of staffing.Footnote 34 This wider context, however, was often absent from tabloid newspapers’ coverage. In such texts, the quantity of hospital beds alone came to dominate public discussion about the NHS. In seeking to communicate “crisis,” bed numbers and waiting times were the most effective and simple tool. But this focus on numbers flattened a more complex issue. In fact, greater attention was paid during this time not only to reducing the amount of time spent in hospital beds, but also to improving the material experience of hospital beds and care. However, these issues were discussed deep in the pages of architectural or medical journals rather than in newspapers for public consumption.

This trend continued into the 1980s, when “care in the community” took hold. The policy is most commonly associated with Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, but the premise, problem, and potential of community-based care had much longer roots, with reducing bed numbers at its center, particularly at large, long-stay institutions. There is a separate, extensive literature on such policies and their limited success, and it is not the purpose of this article to assess whether reducing bed numbers was genuinely “efficient” or made for better quality hospital or psychiatric care.Footnote 35 It is, however, noteworthy that many politicians advocated a reduction in bed numbers for long-stay patients, while simultaneously highlighting “bed shortages” and “waiting lists” for acute patients—particularly when politically expedient. Alongside manifesto promises about investing in new and “larger” hospitals, for example, the Conservative Party made statements such as, “most people who are ill or frail would prefer to stay in or near their own homes, rather than live in a hospital or institution. Helping people to stay in familiar surroundings is the aim of our policy ‘Care in the Community’” (1983).Footnote 36 At the same time, politicians across the political spectrum continued to emphasize the need for greater investment in hospital beds and the reduction of waiting times. In the mid-1980s, a number of health authorities closed beds to cope with budget squeezes but were requested to stop as the 1987 election loomed. Labour's Manifesto for this election declared: “The biggest single deficiency in the NHS today is the excessively high hospital waiting lists which, under the Tories, are increasing year by year. We shall speedily reduce them by computerizing bed allocation.”Footnote 37 In 1987, Frank Dobson, Labour's health spokesman, said, “over the last year there ha[s] been a new epidemic—an epidemic of hospitals short of beds, an epidemic of doctors hunting for beds, an epidemic of patients turned away.”Footnote 38 In 1992, they moved beyond promises of better use of beds to pledge £25 million to resolve the “shortage of intensive care beds.”Footnote 39

Beds—in the form of bed numbers—served a useful political purpose for Labour in opposition. The left-wing Daily Mirror used its bed statistics and dates carefully to make political points, for example, emphasizing in 1995 that one in three hospital beds had been lost “since 1979” when the Conservatives came into power, which was broadly true, although bed numbers had been in decline for decades.Footnote 40 The Conservatives lost on the NHS political “battleground” when—despite their arguments about the increasing number of outpatients moving through hospitals—public perception was that beds were no longer being cut for efficiency and therapeutic reasons, but just to save money.Footnote 41 Beyond media and political “battlegrounds,” discussions about bed numbers still emphasized the importance of thinking about redistribution and equality rather than just numbers. In the early 1990s there was also still a concern that too many hospital beds were concentrated in the capital.Footnote 42 In 1992, the Tomlinson report recommended London hospital closures and mergers to reduce inefficiencies in the city's health services.Footnote 43 However, these debates were largely contained within medical publications such as the BMJ.

The number of NHS hospital beds continued to decline from the 1990s onward. It is noteworthy that, while British bed reduction was already happening from a relatively low starting point in comparison to other countries, almost every European nation witnessed their own decline in bed numbers.Footnote 44 Despite this, there is often a sense in newspaper articles that the hospital beds crisis was and remains a uniquely British phenomenon. The Guardian recently compared NHS figures unfavorably with those of nearby countries, declaring Britain the “sick man of Europe.”Footnote 45 Distinct objects or features of healthcare systems have come to symbolize crisis in different countries. While discussions of healthcare scarcity in the United States have centered on costs and (in)equality, for example, and those in France have often focused on staffing or geographies of access, in the United Kingdom it is the bed that has become the primary focus of debate.Footnote 46

We have demonstrated that there was indeed a decrease in bed numbers over the course of the late twentieth century, but that it was not automatic that these trends should be framed in the language of “crisis” or “bed-blocking.” Opposition parties and tabloid journalists in particular found value in these ways of discussing the bed, which were more attention-grabbing than policies about bed redistribution or efficiency: beds being “axed” was a more emotive tool than beds being redistributed. There were, nevertheless, long-term implications to this kind of rhetoric. The NHS bed was increasingly politicized and deployed as evidence of the health of—or, conversely, the “crisis” in—the system as a whole.

Why was the hospital bed so politically important in relation to the perceived NHS crisis, particularly as its decline was neither a uniquely British phenomenon nor was it a new trend when the language of “crisis” picked up in the 1970s? It is worth turning to the question of “crisis” here, and returning to the 1970s to consider how the bed functioned in relation to this concept or construction. The bed—when framed in numerical terms—became a shorthand for the health of the new NHS as a national system, and this connection was built into political and media discussions from the start. It was highly successful as a communicative device, particularly in the context of this new welfare state. This was because it had embedded, long-term associations with care, but also—in simple terms—spoke to the need to provide access for all. The bed problem took hold in the media when the NHS in general was increasingly perceived and framed as a service in “crisis.” As Jennifer Crane and Agnes Arnold-Forster have both argued, the 1970s also marked the beginning of a new, emotional relationship between the health service and the British public, as well as the emergence of a new, deeply politicized, culture of protest around healthcare provision, resourcing, and access.Footnote 47

The idea of “crisis” has long been recognized as a construction. This is not to deny some of the real challenges that the NHS faced toward the end of the post-war period. Following what Rivett calls the “age of optimism” immediately after the end of the Second World War, the long 1970s has been represented as a dismal decade characterized by crumbling social democracy and the slow fracture of the welfare state.Footnote 48 Rodney Lowe described the mid-1970s as a time of “crisis” marked by high unemployment, industrial action, and a global recession.Footnote 49 However, as Martin Powell points out: “the death of the NHS has been pronounced many times.”Footnote 50 Powell is skeptical of such claims: “Like Mark Twain—accounts of its death have been exaggerated” and the “criterion [for its collapse] is often implicit, unclear or contestable.”Footnote 51 By looking through the lens of the bed as a single object that symbolized this crisis, it is possible both to support and enhance this analysis. The bed confirms Powell's notion that crisis is a construction. Indeed, the long history of the steady decline of hospital bed numbers and the rhetoric of “crisis” did not neatly align with the crisis that it was apparently describing. While some far-sightedjournalists expressed concern over bed numbers in the 1950s and 1960s, fractious media coverage of the “crisis” began in the 1970s, when the decline was already well underway. Powell argues that the NHS has been framed as in a state of perpetual crisis since its inception, but we use the bed to suggest that this particular permutation of crisis rhetoric emerged in earnest in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

This chronology aligns with that posed by Laura Salisbury et al. in their reflection on the NHS crisis and waiting for care.Footnote 52 They argue that, in the early years of the health service, it was acknowledged that “waiting was sometimes the cost of universal care.”Footnote 53 Waiting and accompanying shortages and resource insufficiencies were tolerated because people appreciated that they were “now a patient of the NHS … rather than someone who might never afford health care.”Footnote 54 Waiting, Salisbury et al. argue, “had a place as a collective practice within a shared, social project.”Footnote 55 This changed, however, in the late 1970s and into the 1980s, as the project of the social democratic welfare state started to collapse, and waiting started to signify the failure of the system.Footnote 56

These transformations also shaped the media coverage and political rhetoric around bed numbers. This coverage might explain, to an extent, why some thought that bed numbers had declined to crisis point in the late 1970s, but it does not fully illuminate what this rhetoric was intended to do. Why do people invoke crisis when discussing the NHS, and specifically when talking about beds? Fundamentally, when it comes to beds, the language of crisis is appealing because it is galvanizing, awareness-raising, and attention-grabbing. It was designed to provoke action, intervention, change, and reform. It is simple language, intended to make a simple point. Indeed, the media and many political discussions selectively framed hospital bed numbers in relation to particular problems (“bed-blocking” and waiting lists) while ignoring others (efficiencies and redistribution).

Beds were not the only symbol of crisis in this context, but they were a particularly useful one, in part because bed numbers were such an effective communication device. In practice, though, bed numbers were never the simple representation of health service security that they purported to be. Even taking out the contexts of redistribution, bed numbers always existed in relation to a number of other questions. For example, bed numbers alone were arguably meaningless outside the context of how many people they were meant to be serving, how many staff there were available to treat people in those beds, and other forms of resourcing “the bed.” As noted above, statistics that simply outlined declining bed numbers rarely paid attention to such wider issues. In that sense, it is perhaps obvious—but important to remember—that numbers themselves were also constructed and carefully wielded to grab headlines or meet political agendas. Statistics have been shown to be a particularly compelling communication tool. As one recent study on health journalism argues, “journalists associate statistics with neutrality, objectivity, and empirical evidence … News coverage that cites statistics is considered to be neutral and valued over coverage that cites other less empirical sources such as exemplars.”Footnote 57 While such an attitude to statistics is undoubtedly flawed, it helps to explain why media reports leaned so heavily on bed numbers to communicate the idea of “crisis.”

The hospital bed thus shows how some of the specific perceived qualities of crisis were produced, and particularly the role of tabloid newspapers in flattening out the nuances of a much more complicated picture around NHS hospital provision and access. This flattening also helps us to understand how “the NHS” was brought into being as a somewhat abstract and universal entity, just like the “crisis” in which it has apparently always been in. Finally, this focus on the hospital bed shows its power as a shorthand for “the NHS” itself because of the ways it implicitly brought together ideas about care, recovery, efficiency, investment, infrastructure, and more. As an object that was inherently both emotional and political, the bed thus offered more than many other symbols of “crisis” for those seeking to communicate NHS problems.

The problem is that “crisis,” as a call for action, actually often does the opposite. Rather than making radical change and reform possible, it constrains the range of potential responses. As Salisbury et al. put it, “there is something intrinsic to the structure of crisis that makes a crisis-free future hard to produce.”Footnote 58 Crisis rhetoric circumscribes the “terms of the problem,” and in doing so, prescribes “which actions are legitimate to address it.”Footnote 59 In terms of beds, the language of crisis articulates the problem in simplistic terms: that there are not enough beds in the NHS. Thus, the only way to respond to this crisis is to say that more beds are needed. This idea of “crisis” has also changed the meaning of the hospital bed, layering the political “crisis” on top of its more medical meanings of humanistic care, technology, and efficiency. This meant that it was not just difficult to produce a “crisis-free future,” but that it was impossible to produce a “crisis-free” hospital bed.

Overall “the bed”—as a numerical symbol of “crisis”—became a catch-all stand-in for the problems facing the NHS. There were plenty of rational arguments for a reduction, rather than an increase, in bed numbers, suggesting that public rhetoric about decline was less about the furniture itself and more about the role of the hospital bed as a politically pertinent shorthand for the health of the NHS as an institution. The idea of a bed shortage, or “blocked” beds, communicated such ideas simply and concisely. Controlling the narrative around hospital beds, or rather the meaning and implications of fewer hospital beds, was central to politics because the hospital bed had for so long been a symbol of the NHS itself and a cipher for the standard of NHS care. It supported a version of “the” NHS that was an abstract collective entity, defended by the public and the media across the political spectrum.

The Material Bed

Discussions in the public sphere tended to focus on bed numbers and waiting times, but discussions in the healthcare sector and among policymakers focused more on what beds could and should do for both patients and staff. The idea that fewer, better-designed beds could mean better care—though of course complicated and context-dependent—continued to have some traction in design, architecture, and healthcare circles in the late twentieth century. For many, the hospital bed was not just an abstract concept to be found on the pages of tabloid newspapers. It was a material object, which also underwent important changes in the late twentieth century. Understanding these changes adds even more weight to the argument that much has been lost in the emphasis on hospital beds as numbers—and that other stories about the bed can be told. The story of the material bed runs parallel to, and is interconnected with, that of the apparently crisis-stricken numerical bed, but has its own chronology and temporality. By paying close attention to the material bed, it is possible to go beyond the question of “crisis” and access, to think about the other roles that the bed could play in NHS care. It allows for a political-material story of the late twentieth century that does not hinge on the 1970s as a key point of transformation, and it provides a route into the history of one of the other, multiple versions of the NHS that can be overshadowed by NHS politics. It also offers a way for historians to break free of the cyclical trend (found in historiography, as much as in history) in which, to quote Salisbury et al., “crisis produces more crisis.”Footnote 60

The long cultural history of the hospital bed is crucial to understanding its significance in the NHS after 1948. As the new NHS faced challenges of infrastructure and finance, the hospital bed served a crucial function as a symbol of care and of the system itself. Building on the bed's long-term symbolism, NHS hospitals could present a vision of what they thought modern healthcare would, and should, be. The bed came to represent a complex constellation of meanings that were specific to the NHS, and which had built up over time as a number of different, co-existing aspects of modern healthcare. The NHS should be hygienic, efficient, and technological (these three were most often associated with modernity) and it should also be (in line with long-term ideas about care, and the newer principles of democratic healthcare in the Welfare State) “homely” and “humanistic.”Footnote 61 Rhetorically, the “humanistic” and “homely” were often situated in opposition to the institutional, modern, and technologically-advanced hospital. In practice though, as the hospital bed shows, it was not seen as fundamentally incompatible for a bed to be the site of “humanistic” care, to feel “homely” and comfortable, and to be an efficient piece of machinery. Bed design was key to showing that all of these meanings could co-exist in healthcare, and that efficient technology did not need to come at the expense of care and comfort. These ideas about what the NHS was, or should be, could sometimes be in tension, but more often they co-existed, and the bed came materially to embody all of these ideas.

Although we argue here that this constellation of meanings was a crucial part of the NHS's identity, they did not only come into being in 1948. In Architecture and the Modern Hospital, Julie Willis, Philip Goad and Cameron Logan provide an excellent overview of trends in modern hospital beds, in a chapter called “Everyone's Own Healing Machine.” This chapter shows that the NHS inherited co-existing ideas about modern healthcare—as efficient, high-technology, humanistic, and homely—that had built up over the course of at least a century.Footnote 62 The NHS certainly added new layers of meaning to the bed, particularly the idea of it as a site of negotiation of patients’ rights that was part of “humanization,” but it should not be seen as a dramatic turning point or departure. In this regard, the material bed allows for a different way of thinking about change over time, compared with a more traditional political or social NHS history. It shows how the hospital bed, as an object imbued with meaning accrued over time, was an agent in the making of the NHS hospital. NHS hospital staff, charitable organizations, designers, and architects then responded to and built on these meanings, for example, by redesigning the hospital bed and the layout of wards, as part of seeking to consolidate a particular vision of NHS care. This version of “the NHS” involved gradually moving toward fewer, better beds, in smaller wards, as part of the vision of efficient and caring healthcare. This material bed—and its temporalities—differed from the “numerical bed” discussed above, which emerged as a new phenomenon in the late twentieth century as part of public conversations about the NHS in crisis.

Entering the NHS in 1948, the hospital bed was a complex material symbol. Although Willis, Goad and Logan argue that the bed “as technology” came to replace older meanings, it is perhaps more useful to think of these developments as the building up of many co-existing layers of meaning. Entering the new healthcare system, the hospital bed carried all of these meanings: care, hygiene, homeliness, modernity, and technology. At this point, it did not yet carry the meaning of “crisis.” The bed as material object and site of care thus encapsulated the NHS itself. It is perhaps no surprise that the hospital bed, then, became a renewed focus for conversations about the modern hospital and modern healthcare. At the very beginning of the NHS, articles started to appear in medical journals about the principles of care in large institutions. The hospital bed became a symbol of the need for balance between efficiency and modernity, and care and humanity.Footnote 63 It needed to be more than a place to “lie” or “occupy” to achieve its status as a place of care. In November 1948, for example, one Lancet article “by a patient” observed that:

I could not help comparing the efficiency of a great hospital at work with its comparative neglect of human needs … Nobody seemed to know that a patient, on arrival, needs more than a bed to lie in and a case for her clothes.Footnote 64

Such articles emphasized that the bed could be a dehumanizing or inhumane place if it was poorly designed, or if the staff did not bring it into being as a space of care. The bed always existed in relation to ideas about the staffing, skills, and attitudes of the staff who looked after patients or service users. In 1953, another Lancet article noted that “The Central Health Services Council [CHSC] … warn all who work in hospitals of the danger of thinking of patients as ‘cases,’ and identifying them as—for instance—‘the duodenal in the first bed on the left’” and complained about “the practice, still strangely prevalent, of discussing the patient's more alarming symptoms, across his bed, with a class of students.”Footnote 65 The bed was never conceptualized as an object that could care in its own right, but rather as a material part of a web of relations. Changing the bed itself was one part of starting a conversation about these relations in general and seeking to shift some of the power dynamics of the new—apparently more democratic—healthcare system.

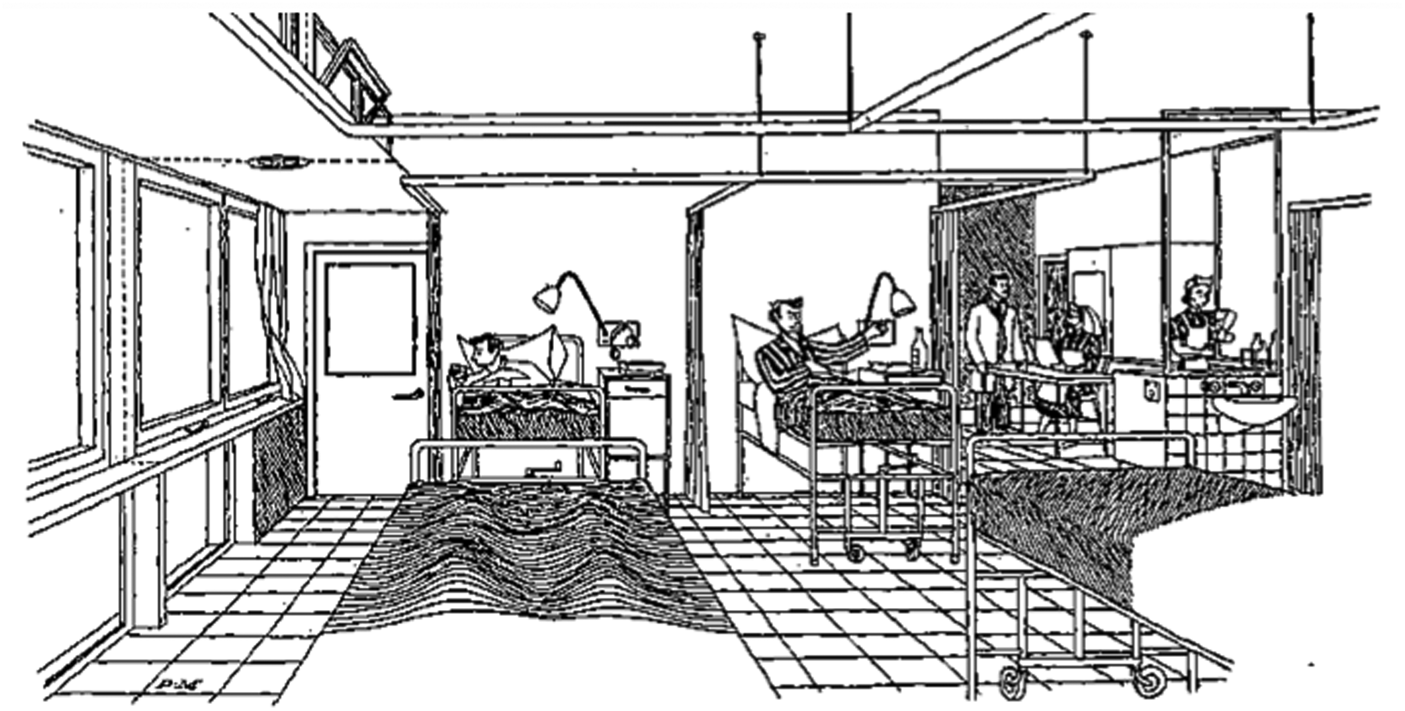

From the very start of the NHS there had been a turn against the idea of Nightingale wards as the ideal layout (where the patient became an impersonal “bed 3”). The Nuffield Trust was an early advocate of the use of smaller four- or six-bed bays. In its 1955 publication Studies in the Function and Design of Hospitals, the Nuffield Trust compared international trends and showed that Scandinavian and American design (the latter drawing on the former) had been using smaller, divided wards since the early twentieth century, but that such wards were still viewed as “experimental” in the 1930s in the United Kingdom.Footnote 66 The Nuffield Trust built some experimental ward units themselves, including at Larkfield Hospital in Greenock. It is notable that their drawings of the scheme, shown in Figure 1, are from the perspective of the top of a bed, in a four-bed unit where the bed is parallel to the window. To some extent moving beds parallel to the window was a decision based on efficient use of space, but it also allowed for patients to see out of a window and benefit from its light, while being protected from glare. The patient's point of view is the focus here, conceptually as well as literally, showing the importance of the bed to ideas about patient experience in the NHS: this way of seeing, from the top of a bed, offered an alternative vision of the ward to traditional floorplans or even photographs of empty spaces as found elsewhere.

Figure 1. “A Ward in the Investigation's experimental ward unit at Larkfield Hospital, Greenock: the patient's view.” Image from Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust, Studies in the Functions and Design of Hospitals (Oxford, 1955), p. 23. Reproduced with kind permission of the Nuffield Trust.

The Nuffield experiment also involved collaboration with a bed designer to make an adjustable bed more suitable for “modern policies of early ambulation” rather than older style beds that were “designed to save the nurses from having to stoop when attending to bedfast patients.”Footnote 67 Although this ward was not representative of common practice at the time, it shows how negotiation around the bed, its placement, its design, and the way the patient experienced it and staff interacted with it were all part of the making of new values in the NHS. Through the lens of the material bed, it is difficult to see the reduction of bed numbers as a symbol of “crisis.” The bed as an object in hospital has its own history, which intersected with political ideas about what the Welfare State should be and its values, but which also carried older meanings about the bed as a site of care and therefore as an opportunity for deinstitutionalization. The politics of the material bed were not about numbers or “crisis,” but rather about values, care, experience, and rights: the material bed was a story of quality, not quantity.

The goal of creating a hospital bed marked by personalization and care was not incompatible with the goal of creating a modern bed, suitable for efficient healthcare work. The co-existence of these ideas was made possible by the longer history of the hospital bed, with its layering of meaning and symbolism. Between 1952 and 1970, for example, a group undertaking a training assessment at Thornbury Hospital devoted space in their regular reports to discussing whether the space, including bedsteads, was “modern” or not. Cubicle curtains were introduced by 1959, and in 1965 they commented that “although the number of beds was reduced when cubicle curtains were installed, the female wards are still rather crowded … Consideration should be given to removing one of the 3 beds in the side wards … to facilitate the nursing care of these ill patients.”Footnote 68 In 1970, they noted the introduction of adjustable-height beds. In such reports, high-quality, modern care was actually linked to a lower number of better-designed beds. The modern hospital needed modern beds, and the design and materiality of beds—including bedside furniture, call systems and technologies, and privacy mechanisms—became central to this goal.

The most famous example of this trend is The King's Fund bed, which was developed by the charity after they were approached by the Ministry of Health in 1963 to develop a standardized hospital bedstead. In 1967, The King's Fund published a new specification for the design of a hospital bedstead after an evaluation of the efficiency of current designs carried out in conjunction with the Industrial Design (Engineering) Research Unit at London's Royal College of Art.Footnote 69 The bed redesign project reflected Enoch Powell's concerns about the need to save money and improve labor efficiency, as standardizing the hospital bed was one possible way to improve nurse productivity and reduce procurement costs.Footnote 70 This redesign and standardization of the hospital bed also reflected another shift in the making of the modern bed: the development of the idea of the bed as both an aid to medical intervention and a form of medical technology itself. The King's Fund bed symbolized what the modern hospital should be. Its design was grounded in extensive, robust research. It increased staff efficiency as well as patient comfort. It brought together the humanistic, the hygienic, and the modern (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The King's Fund hospital bed, Birmingham, England, 1994. Science Museum, London. Wellcome Image Collection. License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

This bed was an efficient technology that “cared,” and The King's Fund also did surveys of mattresses in 1960–63 that ensured the question of comfort was not forgotten.Footnote 71 As Science and Technology Studies (STS) scholars have long shown, acts of “care” have often involved entanglements between people and objects. Technologies have thus never been incompatible with “humanistic” healthcare. Nor, as many commentators on the hospital bed have repeatedly emphasized, could an object on its own—without interaction, or as part of an assemblage of human and non-human actors—provide “care.”Footnote 72 Care in the hospital bed was not only provided by doctors and nurses, but also by people bringing food and by the laundry workers who took great pride in their work as part of the healthcare system.Footnote 73

The King's Fund bed was not the only such project at this time, which in itself is significant. Others, such as the Birmingham Regional Hospital Board, were considering the issue of beds independently in the 1960s through their “endeavour to prepare a ‘draft specification’ for a hospital bed, to give maximum efficiency in use, avoid undue nursing fatigue and strain, facilitate normal nursing and bedside routines, and offer the highest standards of comfort to patients.”Footnote 74 This, in itself, shows the importance of the hospital bed as a site for reform and for the articulation of new healthcare principles. It is significant that these redesigns also came in the wake of the 1962 Hospital Plan, which promised new hospitals with more efficient bed use. The redesign of hospital beds confirmed their role as a tool or technology of recovery, in which people should theoretically spend as little time as possible. This built on medical literature from the 1940s and 1950s that had shown that early ambulation could actually help recovery, with a turn against the idea of a lengthy convalescence in bed as the ideal for patients.Footnote 75 The new NHS bed of the 1960s was designed to improve efficiency of care and, in theory, to be inhabited for less time, with greater comfort. The redesign of the hospital bed was a material representation of these new principles: the aim was not more beds, but better beds. Less time waiting, whether in a seat at the GP surgery or in the bank, was seen as a key marker of modernity at this time, facilitated by better technology in the post-war period. The hospital bed was one such technology.Footnote 76

There is evidence that The King's Fund bed was further adapted for local environments, for example, through color. One Design Guide on improving hospitals for long-stay residents noted the potential value of painting beds in bright colors in 1973: “Where an adjustable bed is needed, some models of the King's Fund bed are not too clinical in appearance. Hospital beds can sometimes be reduced in height and their frames painted in bright colours (in non-chip finish).”Footnote 77 Such comments were not just about adding some color to furniture for aesthetic purposes, but need to be understood in relation to the significance of hospital beds as material sites and symbols of care, a role that grew even more significant from the 1970s as the limited number of beds became a symbol of NHS crisis in the political sphere. At this time the material bed was also politicized: repainting was a political act, or at least can be seen as a response to the political climate. By suggesting painting such beds in bright colors, the Design Guide built on the principle that the beds symbolized care and attention rather than institutionalization. The tone of the advice implied that the limited addition of bright color to selected, meaningful items of hospital furniture and fittings could be a significant change made at a local level, perhaps even by ward staff, rather than as part of an integrated interior design scheme. They made such changes with the needs of patients in mind, although of course the reference to non-chip paint shows they were still mindful of the practical requirements of the hospital setting. The bed was, after all, still a material object that needed to be low maintenance and hygienic alongside symbolizing care: non-chip, wipe-down, brightly colored paint helped it materially to represent all of these ideas. They were not necessarily in tension, but rather were carefully negotiated and always in dialogue.

Material changes to the bed also altered patients’ experiences of hospital. Willis, Goad and Logan suggest that new bed design resulted in changes to hospital architecture. They also note that the technology “of, for and from the bed” radically “liberated the patient from helplessness and complete reliance on doctors and nurses,” and that these technologies grew in complexity over the course of the twentieth century from wheel castors that allowed mobility to fully adjustable beds and bedside communication devices.Footnote 78 It did take some time for hospitals to move toward new models of bed use. New ward layouts, for example, were hindered by the slow building program and the old infrastructure of the early NHS. The new King's Fund bed was popular but took time to be widely rolled out. In the meantime, there were informal and localized efforts to improve the experience of the hospital bed, from attaching curtains for privacy to adding bedside technologies and redesigning the bedstead and mattress.Footnote 79

NHS values continued to be negotiated and articulated through the layout and design of beds, and spaces containing beds, in hospitals. As large district general hospitals started to be built in the 1970s, there were growing concerns that such hospitals were “impersonal” and potentially “dehumanizing.”Footnote 80 For many patients, the bed was supposed to be a place of rest and recuperation, and it therefore became a focal point of complaints about issues such as noise from staff and other patients, a lack of privacy, and discomfort.Footnote 81 The “public” bed of mass wards was ideally a thing of the past, no longer compatible with humanistic, modern healthcare. Over time, six- or four-bed ward units became commonplace, and the model for some designers and architects even became the single-bed hospital room.Footnote 82 Design principles also sought to empower patients and support their experience, with an emphasis on the qualitative experience of beds rather than their number. Rather than a large ward of beds facing away from hospital windows, then, by the late twentieth century many new hospitals had small bays of beds parallel to windows, or single beds facing a view.Footnote 83 This is not to claim that giving patients a view from windows was an entirely new phenomenon in the NHS; indeed, in many older hospitals, particularly sanatoria, patients had been wheeled in their beds onto balconies for a change of view and some fresh air. However, there was a shift in design for patients within wards, and bed positioning increasingly prioritized patients’ experiences over, or at least in combination with, the access needs and convenience of staff.

In general, hospital architecture and design journals published an increasing number of articles on ward design, color schemes, bed positioning, and more. Some hospitals contemplated adding features of interest to hospital ceilings, to reflect the fact that some patients would be resting in a horizontal position, although in practice most ceilings were left white or off-white in wards to allow for rest; ceiling artworks were more popular in corridors where patients on beds might be wheeled through. Where there were concerns about isolation, beds were sometimes built to be private but with a view of other patients. A report in Hospital Development on the conversion of a unit for adolescents at St Mary's in Manchester in 1974, for example, noted that, “separate rooms were necessary and desirable to provide privacy both visual and acoustical at an age when embarrassment and awkwardness are common feelings … When separation was not required, social contact was to be encouraged … Bed head positions are located to give patients a view out of their rooms and across to their neighbours.”Footnote 84 Such careful design, in terms of the material and sensory history of care, was considered to represent the patient-centered principles of NHS care: the hotel-like single room also aligned with the idea of the “patient as consumer” from the 1980s onward.

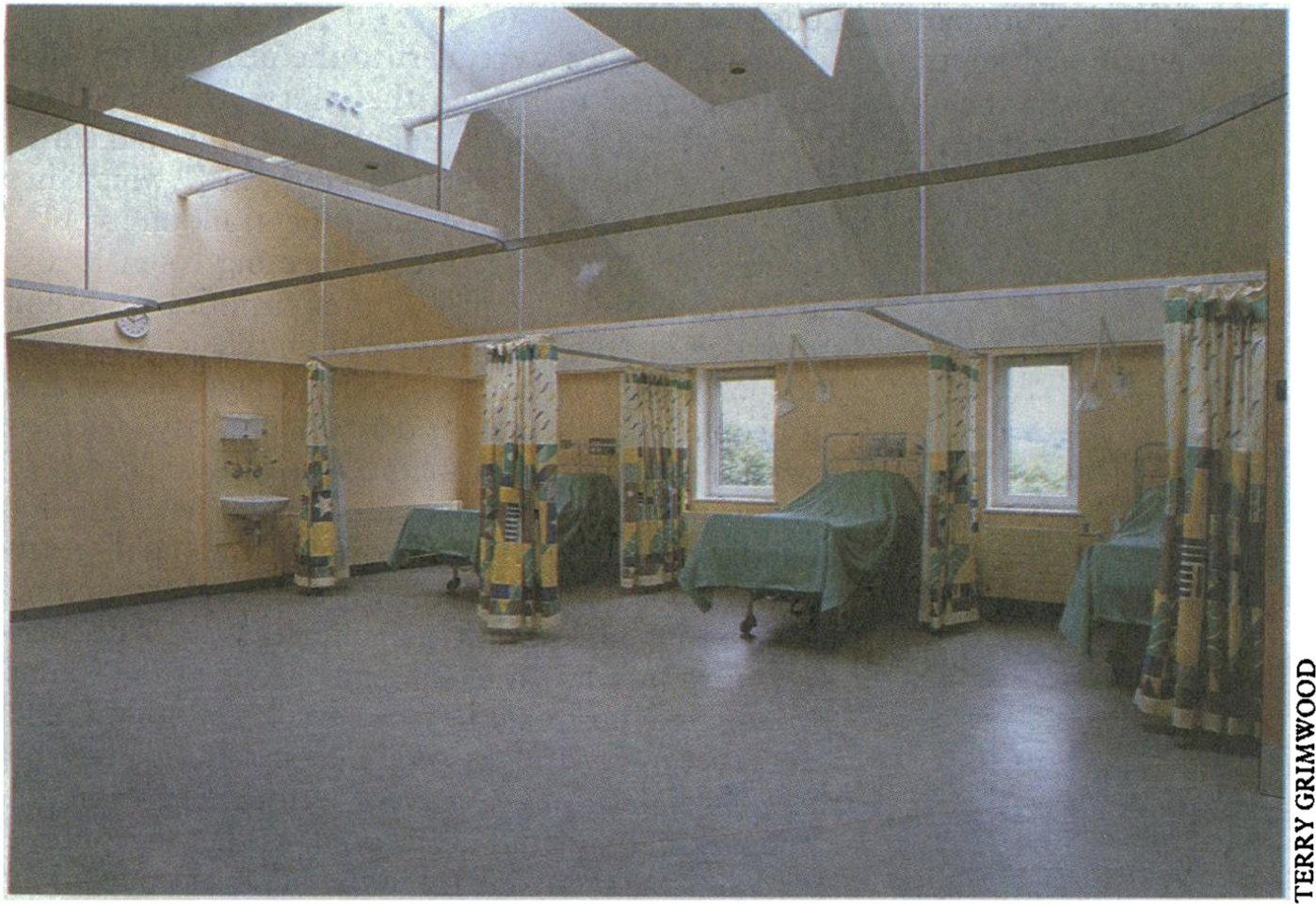

Over the course of the late twentieth century, new color palettes were introduced to bedding and bed curtains to try to make hospital wards feel less clinical (Figure 3). This was particularly important for larger wards, including old Nightingale wards that could not always be rebuilt, and in shared spaces in newer hospitals and smaller units. The Wellcome Library, for example, holds brightly colored bed curtains that were made for St Mary's Hospital on the Isle of Wight in the late 1980s (Figure 4). More recently, there have been concerted efforts to improve the design of bedside lockers, both for hygiene purposes and ease of cleaning, and to enhance their emotional and aesthetic value for patients.Footnote 85 Many of these design interventions were promoted in opposition to the apparently more cold and clinical “modern” hospital of the early twentieth century, although in practice hospitals had always used some color in bedding and “homeliness” was a long-standing goal of hospital design. Overall, by the end of the century the hospital bed was designed to be a more comfortable experience for patients and for staff, and to be a more private space.

Figure 3. Richard Burton, “St Mary's Hospital, Isle of Wight,” BMJ, 22–29 December 1990, 1423, photograph by Terry Grimwood. All best efforts have been made to contact the copyright holder.

Figure 4. Sian Tucker curtains. Wellcome Library, London, ART/IOW/F/1-4. Reproduced with permission of Sian Tucker and the Isle of Wight NHS Trust.

It can be tempting to tidy some of these trends into a “neat” story of the history of NHS beds. It would be possible to select vignettes that illustrate a dramatic change over time in the material and embodied experience of the bed between 1948 and present, from “the duodenal in the first bed on the left” to the bed as a site of embodied personhood and care. It is, indeed, important to recognize that there were some material and spatial advances in relation to the hospital bed. Being in quieter rooms, with fewer beds, more attention given to color and decoration, and better views from windows were all markers of a better quality experience of the bed even in the context of declining quantity. Historians of health, bodies, and materiality, however, also recognize that two experiences of hospitals beds would be just that: two experiences of hospital beds. No two accounts of the hospital bed can be taken as entirely representative of their given point in time. Hospitals have always been extremely varied places that have allowed for a range of encounters between people and beds. It is perhaps more revealing to look for points of commonality within wide-ranging experiences of a single hospital. When The King's Fund did a Patients Satisfaction Survey in London and Yorkshire in the late 1960s, many patients gave positive feedback about the beds and bed layouts when explicitly asked about them. For example, some commented: “The thing I liked best was being in a bedroom of my own”; “small wards of four beds such as I have been in, are much better than bigger wards. You have more privacy… at the same time you have company”; “I liked the privacy behind the curtains which went completely round the bed”; and “my bed was very comfortable.”Footnote 86 Others, in the same beds and same environments, were more critical. For example they complained that: “the sponge pillow becomes hard and very flat after being in bed for a few days”; “the beds were not comfy”; and “patients did not seem to have the same contact with the nurses as they did in the old type large wards.”Footnote 87 Some patients found single rooms isolating and preferred a level of interaction with others. Despite this wide variation in experiences of hospital beds in practice, it remains important that the bed as object or inhabited place was extremely important to staff, patients, and visitors alike. In these conversations, most references to the reduced number of beds were positive, and most discussions of beds focused on issues of quality, comfort, and care rather than on waiting times, access, and numbers. Even those who found the bed physically uncomfortable noted staff efforts to make the bed more comfortable, which were in themselves seen as important acts of care. One patient noted: “For me there was too much weight in the bedclothes, which was adjusted immediately on request. ‘The staff’ did everything they could to make it as comfortable as possible.”Footnote 88 For others, there was a perceived gain of peace and privacy in rooms with fewer beds, at the expense of “contact” with nursing staff. These surveys emphasize the wide range of attitudes to and experiences of beds, but they also underscore the continued association between beds—as a place of rest or lying, as an object in a room, and as a site of human interaction—and quality of care.

Negative comments about the experience of hospital beds also continued to be common throughout this period, a point that is itself worthy of note. The fact that the hospital bed was a focal point of complaints—and features heavily in people's memories of the hospital—supports the argument that the bed remained a symbol of care, and by extension also a focal point when there was a perceived absence of care. In one oral history interview, a British interviewee remembers being in hospital as a child in the 1960s, in a Nightingale Ward with 30 beds where the nurses “were forever tidying the bed even though you were laying in it they pulled the covers up. They wouldn't let you go out of bed to go to the toilet even though I could walk … We were given breakfast in bed and still weren't allowed out of bed.”Footnote 89 In this context, being trapped in bed for a long time is a negative memory. Being served “breakfast in bed” and having the bed constantly tidied was not synonymous with care for a distressed child who felt that they were not “comforted.” Similar comments were made in The King's Fund surveys in the 1960s. When asked what they liked least about staying in hospital, for example, one person responded, “staying in bed” and another wrote “I detest being inactive and lying in bed.”Footnote 90 The bed was not a substitute for care—it was supposed to be the site of care. The perceived absence of care, then, in this scenario becomes conflated with the idea of being trapped and helpless in bed.

The bed's ability to empower patients had its limits. This anxiety about being stuck in bed was part of a much longer history of the bed's role in relation to medical paternalism, deference, and rigid clinical hierarchies. In psychiatric settings, bed rest was designed to calm patients. Lengthy stretches of time spent in bed were infantilizing and, as Monika Ankele has argued, bed treatment for mentally ill people was intended to homogenize patients: “Lying in their beds, their blankets pulled up to their chins, every patient's external appearance was similar to that of the next.”Footnote 91 The bed, Ankele suggests, “took on a structuring function within the hospital space,” orienting doctors and creating a “kind of visible classification of patients.”Footnote 92 Ankele is actually writing about early twentieth-century Germany, but it is interesting to note some of the cross-cultural symbolisms around the modern bed and the connotations of bed rest. Ankele's points also ring true for NHS acute hospital settings where patients could easily be divided into ambulatory and bedridden. Moreover, the bed facilitated surveillance and control, because healthcare professionals walking through the ward could see all of the patients lying in their beds. Patients who were “stuck” in bed were also made vulnerable as they had no choice but to subject themselves to the medical gaze. For many, however, the hospital bed remained a symbol of the process of rest, care, and recovery, assuming that patients did—ultimately—have the opportunity to leave them. The importance of the bed as a symbol of care, rather than disempowerment, relied on the principle of being bed-free at some point in the future. The NHS shift to beds that facilitated early ambulation was part of encouraging this association between beds and recovery, rather than beds and disempowerment, and it was partly—though not always—successful.

Many of the features of the material bed outlined up to now were not specific to the NHS at this time. Ankele shows that the bed played similar material, sensory, embodied, social and cultural roles in Germany, as has Megan Brien in relation to Ireland.Footnote 93 Willis, Goad and Logan's important work on the different meanings of modern beds is also not specific to the United Kingdom. This article is not arguing that the complex layered meanings of the bed were only a feature of the NHS, but rather that the material bed existed in dialogue with the idea of the NHS and was an important site of negotiation for what NHS care looked and felt like in practice. Design features that were international, such as four-bed wards or adjustable and mobile beds, thus carried a specific meaning in the NHS as part of the rise of “patient-centered” care and the negotiation of a new, inclusive, democratic healthcare system. Even the principle of surveying people on their experience of the bed, a particular feature of the NHS and its charities, was part of the making of meaning and experience of the bed within this new system.

The bed was, therefore, an important symbol of the NHS and modern healthcare in both its political and its material form. While these were always interconnected, they also offer distinct stories with their own chronologies. In particular, the material bed offers an insight into more personal stories of hospital care and emphasizes the variety of people who passed through NHS hospital beds; this multiplicity differs from the more homogenizing numbers found in media stories of “patients,” “waiting lists,” and “beds.” Material beds were also a fundamentally qualitative feature of hospitals. As part of making “good” (rather than “efficient”) NHS care, fewer beds—when carefully designed—could actually be an indicator of a better hospital experience. Units or wards with fewer beds were hailed in architectural publications as more “homely” and “comfortable.”Footnote 94 In 1982, Susan Black wrote in Hospital Development of the progress in hospital interior design of which beds played a key part:

Twenty years ago … [patients] found themselves neatly filed in a narrow bed in a drably-tiled ward (reminiscent of a large public convenience), complete with decidedly unpleasant curtains and bedspread, dark brown or green courted floor of indeterminate composition, and a “stack” in the centre bearing weary flowers and curling X-rays. Today, hospital interior design has taken on a new lease of life.Footnote 95

Discussions about these kinds of design principles are evident throughout a range of historical sources from this period, from architecture publications to patients’ letters and medical journals.Footnote 96 In many of these sources, there is a sense of progress over the course of the late twentieth century in the aesthetics of the hospital bed, including having fewer beds in wards, smaller units, and more “human-scale” hospital buildings. This understanding of the hospital bed differs from that more commonly presented in the public sphere where, by the 1980s and 1990s, the bed was a numerical or statistical entity rather than just a material, emotional, and sensory one.

Conclusion: The End of the Bed?

In 1995, Norman Vetter noted in The Guardian that NHS hospital beds are “disappearing fast and have been doing so for many years … A projection of trends since 1951 indicates that the last NHS bed will vanish in 2014.”Footnote 97 This prediction has not quite come to pass, although in 2013, the British Medical Journal published an article by John Appleby of The King's Fund entitled “The Hospital Bed: On its Way Out?” This article noted the long-term decline in hospital bed numbers and the increasingly “efficient” use of beds, with patients spending less time in hospitals. The question he poses, to close the piece, is this: “Is the hospital slowly but inexorably on its way out to be replaced perhaps by ‘virtual wards’ and new configurations of care facilities? Or are we already close to the limit of substitution and technology development that would allow significant further reductions?”Footnote 98 Appleby's questions are important and timely but focus on the technical side of the hospital bed. Whether the hospital bed is on its “way out” is, here, framed as a matter of technology and feasibility, with an implicit assumption that the aim of the modern hospital is for patients to be in bed for as little time as possible. The future of the hospital bed, in this model, might be one that is found increasingly online or in the home. However, as this article has shown, the hospital bed is a vital social, cultural, economic, and political symbol. The promise of a hospital bed has come to be synonymous with NHS care and with the health of the system as a whole. Over the course of the health service's history, the absence of beds often represented not modernity and efficiency, but “crisis.” The significance of the hospital bed as symbol therefore may restrict what is possible in terms of NHS reform, not only as a problem of technology, but also as one of culture.

This article has outlined two broad ways in which the bed represented the new NHS in the late twentieth century. The material bed was a way of creating the “modern” NHS hospital. In this context, the bed was a symbol of both efficient and high-quality care, and fewer beds were theoretically desirable. For many in hospitals at this time, the goal was to have fewer, better beds, including not only the well-designed King's Fund bed, but also beds organized with regard to comfort, views, and privacy. Layered on top of this vision of the “modern” NHS hospital was a new political and economic story in which the bed was highly symbolic of scarcity, cuts, and under-resourcing. The new articulation of bed shortages as a “crisis” reveals a shift in public rhetoric around hospital beds toward the end of the twentieth century. The effectiveness of the scarce or absent “hospital bed” as symbol relied on cross-party popular and political sentiment about the NHS and what it represented to people, as a national institution worthy of protection.Footnote 99 Bed numbers, as a marker of the NHS under threat, could be easily wielded by both sides of the political spectrum as apparent evidence either of the economic, political, and healthcare failures of the opposition, or as evidence of their own plans for investment in healthcare infrastructure.

The scarce or absent hospital bed was to some extent a political and media construction. To claim this is not to deny that there was a numerical loss of beds over the course of the late twentieth century, nor to deny that such a loss of beds caused many problems. The purpose of this article is not to assess whether the decline in hospital bed numbers was a “good” or a “bad” thing, but rather to show that there have always been many possible narratives about the hospital bed: politicians, newspapers, doctors—and indeed historians—have always made choices about which of those narratives are given attention, which has had significant implications for the way that change over time has been understood. Rather than “crisis,” the decline in bed numbers might have meant: greater efficiency, fairer distribution of beds, or an increase in personal “humanistic” care. As Salisbury et al. argue, waiting—and in our case a lack of beds—“is not simply care's opposite.”Footnote 100 In practice, these different stories of the hospital bed are not incompatible. However, they spoke to different narratives around the NHS and the care it could provide, and they were used in different ways. Stories of the numerical decline of hospital beds served a valuable political function and spoke to public ideas of “the NHS” as an abstract idea or institution. The material bed, or the decline of bedrest, as an indicator of medical progress spoke much more to idea of the NHS hospital as a site of care. In showing this, it is possible to understand not only the value and role of the bed as a symbol in modern political and medical history, but also to start to break down the idea of “the NHS” as a single, unified entity.

These arguments relate to much more than the history of the hospital bed. Here, we have used the bed as a route into a better understanding of what “the NHS” means in the public imagination, and to explore the long-term tensions between on-the-ground healthcare in NHS hospitals and more political and abstract visions of “the NHS” as a crisis-stricken institution in need of public protection. These two issues and conceptualizations have of course always been entwined, as political decisions and public sentiment shape NHS provision and infrastructure. However, it is important to recognize them also as distinct. By focusing on subjects such as the economics, politics, or culture of the NHS, historians sometimes start with the assumption that “the NHS” is an inherently coherent institution. The hospital bed, which cuts across many different aspects of NHS history, from the material to the economic, helps to reveal the differences between “the NHS” in public imagination and some of its more practical and experiential elements. In addition to the specific arguments made here about NHS history, there is a bigger case to be made about the ways in which we approach and structure historical studies. Taking one object, and examining it in a multi-disciplinary way, can open up new historical understandings that bring together different approaches or ways of ordering history.