After the second wave of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, far-reaching consequences have emerged. The impact of the pandemic on the mental health of health-care workers (HCWs) providing care during this crisis has been notorius. 1 Studies have shown that over a quarter of the health-care workforce has experienced mental health issues, Reference Pappa, Ntella and Giannakas2,Reference Saragih, Tonapa and Saragih3 such as increased depression, anxiety, and stress throughout the pandemic. Reference Chen, Liang and Li4–Reference Kang, Li and Hu7 Out-of-hospital emergency medical services (EMS) professionals, in particular, have reported sleep disruptions, anxiety, stress, and depressive symptoms, Reference Soto-Cámara, García-Santa-Basilia and Onrubia-Baticón8 surpassing those experienced by non-first line HCWs. Reference Zhu, Sun and Zhang9 This unique group of workers faces violence, aggression, and traumatic situations regularly, Reference Bennett, Williams and Page10 making them more vulnerable to mental health disorders compared with other HCWs. Reference Almutairi, Al-Rashdi and Almutairi11 The literature describes a higher prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress and an increased risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in out-of-hospital EMS professionals. Reference Bentley, Mac and Wilkins12,Reference Eiche, Birkholz and Jobst13 In the first stages of the pandemic, this professionals in Spain showed PTSD levels far above those reported in previous studies. Reference Martínez-Caballero, Cárdaba-García and Varas-Manovel14

Moreover, the initial challenges faced by health-care systems in managing the high mortality rate and rapid transmission of COVID-19 have further exacerbated the psychological strain on HCWs. Reference Diaz Villanueva, Lada Colunga and Villanueva Ordóñez15,Reference Dami and Berthoz16 It is expected that these effects will persist over time. Reference Greenberg, Docherty and Gnanapragasam17 Therefore, understanding the mental health status of HCWs, especially those in out-of-hospital EMS, is crucial for implementing targeted interventions and improving psychological resilience within health-care systems.

EMS is defined as a comprehensive system that provides timely out-of-hospital care to critically ill victims of sudden and life-threatening injuries to prevent needless mortality or long-term morbidity and disability. Reference Al-Shaqsi18,Reference Handberry, Bull-Otterson and Dai19 That is why the function of the emergency coordination center (ECC) is essential, because it receives and manages urgent care demands and mobilizes different resources to the incident. Reference Handberry, Bull-Otterson and Dai19 Click or tap here to enter text. Worldwide, there are 2 principal models of out-of-hospital EMS based on how health care is delivered. Reference Al-Shaqsi18 In the Franco-German model, based on the “stay and play” philosophy, health care is provided by a team of HCWs (physician, nurse, and emergency medical technicians [EMTs]), who stabilize and treat the patient AT THE site of the incident before hospital transfer if necessary. Reference Dick20 On the contrary, in the Anglo-American model, based on the “scoop and run” philosophy, health care is provided by paramedics, guided telematically by hospital medical personnel, who transport the patient to the hospital as quickly as possible. These professionals work together as a team, using their individual competencies to provide immediate assistance and stabilize patients before hospital transfer if necessary. Reference Roudsari, Nathens and Arreola-Risa21 The Spanish out-of-hospital EMS follows the Franco-German model, and its management is transferred to the different Autonomous Communities. Reference Castro Delgado, Cernuda Martínez and Romero Pareja22

Self-efficacy, a concept rooted in social cognitive theory, plays a significant role in emergency settings. According to Bandura’s theory, self-efficacy plays a pivotal role in the execution of behavior, as it greatly influences the connection between knowledge and action. Self-efficacy is a major factor in self-regulation and a significant predictor of physical and psychological health in difficult times. Reference Bandura23,Reference Karademas and Thomadakis24 Studies have explored the relationship between perceived stress and self-efficacy during the pandemic, indicating that higher self-efficacy can protect against negative mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, stress, and fear. Reference Bandura25–Reference Simonetti, Durante and Ambrosca27 Recognizing the potential impact of self-efficacy on psychological management, it becomes essential to examine how self-reported symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, and self-efficacy differ among different occupational groups.

Therefore, this study aims to assess the occurrence of self-reported symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, and self-efficacy in the different professional categories within the Spanish out-of-hospital EMS. Reference Mahmud, Hossain and Muyeed28,Reference Maiorano, Vagni and Giostra29

Methods

Study Design and Sample

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted, using a nonrandom sampling approach, using a self-completed questionnaire survey. The sample included all active Spanish out-of-hospital EMS professionals, who were on duty during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, and voluntarily expressed their wish to participate by completing the survey. The sample size was determined to be 1066 participants with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 3%. Ultimately, a total of 1666 professionals, including physicians, nurses, and EMTs, were enrolled for the purpose of this study, providing a diverse representation of the out-of-hospital EMS workforce.

Data Collection

The e-Encuesta® survey platform was used. Data were collected for 3 months between February 1, 2021, and April 30, 2021. The survey was distributed through the Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine (SEMES) and its Prehospital Emergency Research Network (RINVEMER). All the Spanish Autonomous Communities were recruited and invited to send the survey to their workers through official channels. The survey was distributed to the employees’ corporate email addresses, with a restriction of 1 submission per person, and the addresses were reviewed to prevent multiple responses from the same individual. To ensure anonymized results, the survey platform used a numbering system to assign a unique identifier to each participant. The first part of the survey explained the objective of the study and its voluntary and anonymous nature to potential participants, with a request for their consent to continue. The time required to answer the survey was approximately 10 to 12 min. The participants were informed of the possibility of withdrawing from the study at any time without further justification. Only fully completed questionnaires were considered for subsequent analysis.

Variables and Measuring Instruments

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

The instrument used to measure stress, anxiety, and depression was the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, based on the adaptation for the Spanish population by Badós López et al. (DASS-21). Reference Badós López, Solanas and Andrés30 This instrument consists of 21 items in which the subjects are asked to evaluate their experience of depression, anxiety, and stress during the week before the survey.

The “Depression” subscale contains 7 items on dysphoria, hopelessness, devaluation of life, self-depression, lack of interest/involvement, anhedonia, and inertia. The “Anxiety” subscale has 7 items related to autonomic arousal, skeletal muscle effects, situational anxiety, and subjective experience of anxious affect. The “Stress” subscale comprises 7 questions on the difficulty in relaxing, nervous excitement, feeling easily annoyed/agitated, becoming irritated quickly/over-reactive, and impatience.

Each item has a 4-point Likert scale. The rating options are “never applies to self” (0 points), “some degree/some of the time” (1 point), “considerable degree/a good amount of the time” (2 points), and “a lot/most of the time” (3 points). The score for each subscale is the duplicate sum of the 7 items. The scale value ranges from 0 to 42 points. The highest values are related to worse mental health.

The DASS-21 manual determines an individual’s level of depression, anxiety, and stress based on each subscale’s score on the following criteria. Reference Lovibond and Lovibond31 For depression, the criteria were set as follows: normal (0-9 points), mild (10-13 points), moderate (14-20 points), severe (21-27 points), and extremely severe (28-42 points). For anxiety, the standards were as follows: normal (0-7 points), mild (8-9 points), moderate (10-14 points), severe (15-19 points), and extremely severe (20-42 points). For stress, the criteria were as follows: normal (0-14 points), mild (15-18 points), moderate (19-25 points), severe (26-34 points), and extremely severe (35-42 points). DASS-21 has good discriminant validity in screening for mental disorders, with good psychometric properties. Reference Mitchell, Burns and Dorstyn32

Self-efficacy

To assess the self-efficacy of the participants, the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE-S) developed by Baessler and Schwarzer 1996, Reference Baessler and Schwarzer33 was used with the adaptation for the Spanish population by Sanjuán Suárez et al. and Bermúdez. Reference Sanjuán Suárez, Pérez García and Bermúdez Moreno34,Reference Schwarzer, Jerusalem, Weinman, Wright and Johnston35 The GSE-S examines the perception of personal control over one’s actions, capturing an individual’s belief in their capacity for self-realization and the ability to direct their life’s course actively and autonomously. It encompasses a sense of confidence in effectively managing various life stressors. Comprising 10 items rated on a 10-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = I do not agree/does not describe my experience at all to 10 = I totally agree/describes my experience perfectly), the GSE-S yields scores ranging from 10 to 100 points, with higher scores indicating greater levels of self-efficacy. Reference Sanjuán Suárez, Pérez García and Bermúdez Moreno34 This scale exhibits robust psychometric properties, demonstrating predictive validity in assessing coping styles and internal consistency with a coefficient of 0.87. Reference Grimaldo Muchotrigo36

Other Variables

Secondary variables related to the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants were collected, such as gender (male or female), age, professional category (physician, nurse, or EMT), and professional experience.

Statistical Analysis

Qualitative data were summarized using absolute frequencies (n) and percentages (%). Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation if they followed a normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test); otherwise, for non-normally distributed variables, the median and interquartile range (IQR = P75-P25) were used.

The possible relationship between the levels of stress, anxiety, depression, and self-efficacy and the professional category of the participants was analyzed by hypothesis testing with parametric or nonparametric tests, depending on their characteristics. The analysis was performed by segregating the values of the results of depression, anxiety, and stress variables in 2 categories: normal, mild, and moderate values and severe and extremely severe values. To assess the association between these categorized scales and the professional category, Pearson’s chi-squared test was used. The relationship between the professional categories and the raw scores of the GSE-S were analysed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis test according to the parametric or nonparametric behavior of the scale, respectively, and the Bonferroni correction technique was applied for post hoc comparisons. Simple logistic regression models were used to obtain the odds ratio of severe or extremely severe depression, anxiety, and stress for each occupational group.

All statistical calculations were performed using the SPSS statistical program (version 25.0 IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). A P-value of ≤0.05 was considered to show statistically significant differences.

Data Confidentiality and Ethical Assessment

The participants were informed of the ethical principles of confidentiality, personal data protection, and guarantee of digital rights in force in Spain. The study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki, and it has been approved by the Valladolid East Area Ethics Review Board (Castilla-León, Spain); Registration PI20-2052.

Results

Description of Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

This study presents a sample of 1666 out-of-hospital EMS HCWs from the whole territory of Spain, including the 17 autonomous communities and 2 autonomous cities, Ceuta and Melilla.

The sample comprised 833 (50.0%) men, 829 (49.7%) women, and 4 persons (0.3%) with nonbinary gender identity; with a mean age of 44.3 ± 9.9 y (range, 19-67 y), and a mean professional experience in EMS of 15.4 ± 9.1 y. There were 739 (44.4%) EMTs, followed by 474 (28.4%) nurses, and 453 (27.2%) physicians. The characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Description of the socio-demographic characteristics and comparison between variables according to the different occupational groups (physicians, nurses, and EMTs)

Presentation of Sample Values for Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and Self-Efficacy

Depression

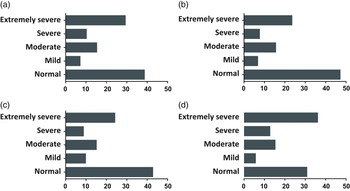

The results obtained from the study sample showed an average score of 15.7 ± 11.1 out of 42 on the Depression subscale. According to the criteria established in the DASS-21 manual, the average score obtained in the Depression subscale is classified as moderate. A total of 554 (33.3%) participants were classified as normal, 192 (11.5%) mild, 411 (24.7%) moderate, 206 (12.4%) severe, and the remaining 303 (18.2%) had values classified as very severe (Figure 1A). Within the physicians group, 172 (38.0%) were classified as normal, 61 (13.5%) as mild, 101 (22.3%) as moderate, 43 (9.5%) as severe, and 76 (16.8%) as extremely severe (Figure 1B). Within the nurses group, 181 (38.2%) were classified as normal, 50 (10.5%) as mild, 118 (24.9%) as moderate, 52 (11.0%) as severe, and 73 (15.4%) as extremely severe (Figure 1C). Within the EMTs group, 201 (27.2%) were classified as normal, 81 (11.0%) as mild, 192 (26.0%) as moderate, 111 (15.0%) as severe, and 154 (20.8%) as extremely severe (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Percentage of overall participants (A, n = 1666), physicians (B, n = 453), nurses (C, n = 474), and EMTs (D, n = 739) showing normal (0-9), mild (10-13), moderate (14-20), severe (21-27), and extremely severe (28-42) score in the Depression subscale of the DASS-21. Reference Badós López, Solanas and Andrés30,Reference Lovibond and Lovibond31

Anxiety

The results obtained from the study sample showed an average score of 13.0 ± 11.1 on the anxiety questionnaire, classified as moderate according to the DASS-21. Taking this scale into account, a total of 642 (38.5%) participants were classified as normal, 117 (7.0%) mild, 253 (15.2%) moderate, 168 (10.1%) severe, and the remaining 486 (29.2%) had values classified as very severe (Figure 2 ª).

Figure 2. Percentage of overall participants (A, n = 1666), physicians (B, n = 453), nurses (C, n = 474), and EMTs (D, n = 739) showing normal (0-7), mild (8-9), moderate (10-14), severe (15-19), and extremely severe (20-42) score in the Anxiety subscale of the DASS-21. Reference Badós López, Solanas and Andrés30,Reference Lovibond and Lovibond31

Within the physicians’ group, 213 (47.0%) were classified as normal, 30 (6.6%) as mild, 70 (15.5%) as moderate, 34 (7.5%) as severe, and 106 (23.4%) as extremely severe (Figure 2B). Within the nurses’ group, 202 (42.6%) were classified as normal, 46 (9.7%) as mild, 71 (15.0%) as moderate, 41 (8.6%) as severe, and 114 (24.1%) as extremely severe (Figure 2C). Within the EMTs’ group, 227 (30.7%) were classified as normal, 41 (5.5%) as mild, 112 (15.2%) as moderate, 93 (12.6%) as severe, and 266 (36.0%) as extremely severe (Figure 2D).

Stress

The results obtained from the study sample showed an average score of 20.5 ± 11.0 on the stress questionnaire, classified as moderate according to the DASS-21. Considering this scale, a total of 541 (32.5%) participants were classified as normal, 197 (11.8%) mild, 310 (18.6%) moderate, 371 (22.3%) severe, and the remaining 247 (14.8%) had values classified as very severe (Figure 3 ª).

Figure 3. Percentage of overall participants (A, n = 1666), physicians (B, n = 453), nurses (C, n = 474), and EMTs (D, n = 739) showing normal (0-14), mild (15-18), moderate (19-25), severe (26-34), and extremely severe (35-42) score in the Stress subscale of the DASS-21. Reference Badós López, Solanas and Andrés30,Reference Lovibond and Lovibond31

Within the physicians’ group, 158 (34.9%) were classified as normal, 58 (12.8%) as mild, 83 (18.3%) as moderate, 91 (20.1%) as severe, and 63 (13.9%) as extremely severe (Figure 3B). Within the nurses’ group, 185 (39.0%) were classified as normal, 52 (11.0%) as mild, 81 (17.1%) as moderate, 93 (19.6%) as severe, and 63 (13.3%) as extremely severe (Figure 3C).

Self-efficacy

The results obtained from the study sample showed a mean score of 70.7 ± 15.8 on the self-completed General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) (Figure 4 ª). Physicians had an average score of 71.8 ± 15.4 (Figure 4B). Nurses had an average score of 70.0 ± 15.9 (Figure 4C). The EMTs had an average score of 70.5 ± 15.8 (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Self-efficacy results for overall participants (A, n = 1666), physicians (B, n = 453), nurses (C, n = 474), and EMTs (D, n = 739) range from 10 to 100. Reference Schwarzer, Jerusalem, Weinman, Wright and Johnston35

Comparative Analysis of Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and Self-Efficacy Across Professional Categories

Depression

Analyzing the percentage of EMS workers classified as severe or extremely severe, no significant differences were observed between physicians and nurses (26.3% vs 26.4; P = 0.972), but significant differences were observed between physicians and EMTs (26.3% vs 35.9%; P = 0.001) and between nurses and EMTs (26.4% vs 35.9%; P = 0.001). Taking this into account, it was observed that working as a EMTs has greater odds of severe or extremely severe depression vs the physicians’ group (OR: 1.569; 95% CI: 1.213-2.030) and vs nurses (OR: 1.561; 95% CI: 1.211-2.012).

Anxiety

Considering the percentage of EMS workers classified as severe or extremely severe, no significant differences were observed between physicians and nurses (30.9% vs 32.7%; P = 0.557), but significant differences were observed between physicians and EMTs (30.9% vs 48.6%; P < 0.001) and between nurses and EMTs (32.7% vs 48.6%; P < 0.001). Taking this into account, it was observed that working as a EMTs has greater odds for severe or extremely severe anxiety vs physicians (OR: 2.112; 95% CI: 1.652-2.701) and vs nurses (OR: 1.944; 95% CI: 1.529-2.701).

Stress

When analyzing the percentage of EMS workers classified as severe or extremely severe, no significant differences were observed between physicians and nurses (34.0% vs 32.9; P = 0.727), but significant differences were observed between physicians and EMTs (34.0% vs. 41.7%; P = 0.008) and between nurses and EMTs (32.9% vs 41.7%; P = 0.002).

Taking this into account, it was observed that working as EMTs has greater odds for severe or extremely severe stress vs physicians (OR: 1.387; 95% CI: 1.088-1.770) and vs nurses (OR: 1.457; 95% CI: 1.145-1.854).

Self-efficacy

No statistically significant differences were observed in the comparison between the professionals (P > 0.05).

Discussion

The present study analyzed the prevalence of self-reported depression, anxiety, stress, and self-efficacy across different occupational groups within out-of-hospital EMS after the second wave of the pandemic. Associations were found among rofesional categories and depression, anxiety, and stress. However, there was no significant relationship disclosed between self-efficacy and rofesional categories. These findings align with previous research demonstrating a higher prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among health-care professionals in different occupational settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reference Pappa, Ntella and Giannakas2,Reference Saragih, Tonapa and Saragih3,Reference Sahebi, Nejati-Zarnaqi and Moayedi5,Reference Sharma, Mudgal and Thakur37,Reference Ghahramani, Kasraei and Hayati38 Factors such as not being a physician and working on the front line have emerged as contributors to increased vulnerability to mental health issues. Reference Moitra, Rahman and Collins39

It is worth noting that most studies observing HCWs have focused exclusively on hospital settings, but the response may differ in the out-of-hospital setting. Reference Zhu, Sun and Zhang9 In fact, Soto et al. Reference Soto-Cámara, García-Santa-Basilia and Onrubia-Baticón8 after an exhaustive systematic review of the obsto f found a greater psychological impact among out-of-hospital professionals compared with other settings such as Primary Care Health Centers or Hospital Emergency Departments. Reference Soto-Cámara, García-Santa-Basilia and Onrubia-Baticón8 The scarcity of studies involving out-of-hospital staff complicates result comparisons. However, it is crucial to emphasize that the care provided in hospital emergency and critical care departments closely resembles that in out-of-hospital settings. The primary distinction lies in physical location: hospitals offer specialized, spacious environments, whereas ambulances or helicopters feature confined cabins with limited equipment. A study has shown that working conditions in an ambulance are more prone to coronavirus infection. Reference Lindsley, Blachere and McClelland40

During the early months of the pandemic, HCWs experienced insecurity due to resource and information shortages, as well as fear of infection. These concerns significantly impacted their mental well-being. Reference Juliana, Mohd Azmi and Effendy41 This research validates the obsto f of heightened mental health challenges among EMS personnel in Spain amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

In a study conducted in Sarajevo in a hospital setting using the same DASS-21 scale, researchers reported a high prevalence of depression (46.5%), anxiety (61.4%), and stress (36.9%), with anxiety levels particularly associated with fear of the unknown. Reference Pašić, Štraus and Smajić42 In the present study, conducted approximately 1 y after the pandemic’s onset and following its second wave, a substantial prevalence of depression (66.7%), anxiety (61.5%), and stress (67.5%) was observed among surveyed EMS workers. Particularly, the prevalence of depression and stress was higher in our study compared with the aforementioned research conducted by Pašić et al. Reference Pašić, Štraus and Smajić42 As the pandemic progressed and more stable action protocols were established, health-care professionals had time to obsto f their actions, leading to feelings of guilt, frustration, regret, and ineffectiveness. Reference Junaid Tahir, Tariq and Anas Tahseen Asar43 Because this study was conducted after the second wave, the observed effect might have occurred within the sample. However, assurance is elusive, as there are no data available before the mentioned period within the sample.

All occupational groups in the study demonstrated high levels of self-efficacy, likely stemming from the well-developed skills of out-of-hospital emergency workers who routinely ite uncertain and urgent situations. Reference Mock, Wrenn and Wright44 This aligns with existing iteratura suggesting that self-efficacy, along with coping skills, altruism, and organizational support, acts as a protective factor against mental health problems. Reference Schneider, Talamonti and Gibson45

According to the systematic review by Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Talamonti and Gibson45 self-efficacy functions as a buffer against psychological distress, especially when bolstered by positive social support. Additionally, the study noted that, during the outbreak, a combination of altruistic risk-taking and stronger self-efficacy perceptions led to reduced likelihood of experiencing depressive symptoms. Reference Schneider, Talamonti and Gibson45 Health-care professionals with high levels of self-efficacy cope more effectively with difficulties and strive to increase their productivity, satisfaction, motivation, and adaptability, which contributes to positive work outcomes. Reference Bargsted, Ramírez-Vielma and Yeves46

Bernales-Turpo et al. Reference Bernales-Turpo, Quispe-Velasquez and Flores-Ticona47 suggested that job involvement mediates the effect of job self-efficacy on job performance, and that self-efficacy provides employees with the skills and resources to improve their performance. Reference Bernales-Turpo, Quispe-Velasquez and Flores-Ticona47 Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, a Madrid study found significant links between perceived stress, self-efficacy, resilience, and physical and mental health. The findings indicated that higher self-efficacy and resilience were linked to lower levels of perceived stress and better overall health outcomes. Reference Peñacoba, Catala and Velasco48

Furthermore, improved social support has also been shown to increase self-efficacy in the first wave. Reference Xiao, Zhang and Kong49 The strong feeling of teamwork generated at work may reinforce the feeling of social support. This, together with the ability to solve complex situations on a regular basis, could explain these non-significant differences in self-efficacy scores. Nonetheless, it is essential to conduct comprehensive studies to definitively establish these conclusions.

When comparing the physician category to nurses and EMTs, this study revealed that physicians exhibited lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. These findings are consistent with the results obtained in another Spanish study. Reference Torrente, Sousa and Sánchez-Ramos50 Research conducted before the pandemic showed that increased emotional responses of physicians were associated with a higher degree of accountability and frustration. Reference Barona, Sánchez and Moreno Manso51 The above fact was not observed in the current study, where the physicians showed levels closer to normal ob the obsto the categories for depression, anxiety, and stress. The results of this study are in line with the results of the work carried out during the pandemic with physicians and medical students in Pakistan, where low levels of anxiety (2.4%) and depression (11.9%) were found. Reference Junaid Tahir, Tariq and Anas Tahseen Asar43 In the case of the research presented in this article, the figures for anxiety and depression in doctors are slightly higher. The difference may lie in the fact that only EMS doctors were studied, but this is not certain, as more studies are needed to investigate this obsto.

Focusing on nurses, the scientific obsto f presents findings parallel to those of this study regarding the effects of the pandemic on their mental health. In the current study, physicians and nurses show a considerable similarity, with no major differences found. However, variations emerge when comparing them to EMTs, with the latter group being the most affected. In general, the authors report higher levels of psychological impact among nurses ob among doctors in hospitals. Reference De Kock, Latham and Leslie52 A study in a Spanish hospital indicates that doctors were more often frustrated, and nurses felt sadder. Reference García-Fernández, Romero-Ferreiro and Padilla53 When focusing on nurses within a hospital setting, we observed greater symptoms of depression and anxiety compared with physicians. Reference Moitra, Rahman and Collins39,Reference García-Fernández, Romero-Ferreiro and Padilla53 The obsto f shows diverse results in this regard, although the findings of the present study do not uncover major differences between physicians and nurses, the levels of psychological impact tend to be higher among nurses in most studies. Another multi-center study conducted in 34 hospitals in China concluded that nurses, and especially women, experienced a greater deterioration of their mental health compared with other obsto fl categories. Reference Lai, Ma and Wang54 Nurses who were most exposed to infection in India reported high levels of anxiety and stress, results that resemble those found in this study. Reference Sharma, Mudgal and Thakur37 A meta-analysis incorporating cross-sectional descriptive studies involving 42,222 nurses from 13 countries highlighted ob mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, stress, insomnia, and post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as instances of physical and psychological violence in the workplace during the pandemic. Reference Varghese, George and Kondaguli55 Comparing the results of this study with the findings of a systematic review by García-Vivar et al., Reference García-Vivar, Rodríguez-Matesanz and San Martín-Rodríguez56 it appears that out-of-hospital nurses experience a greater prevalence of moderate to severe depression (48.6% vs 38.79%) and anxiety (47.7% vs 29.55%), although this should be verified by statistical tests to indicate whether the differences are indeed significant.

The group of EMTs is the most affected compared with other obsto fl categories as seen in this research. There are studies that examine pre-pandemic mental health among EMTs, such as a study in which EMTs scored high on anxiety due to working conditions, violence by patients, and working hours. Among the results of the aforesaid study was that the longer the time spent working in outpatient care, the lower the likelihood of anxiety. Reference Mock, Wrenn and Wright44 A meta-analysis that examines depression, anxiety, and stress among first responders reveals a substantial prevalence across all groups, with paramedics reporting depression rates (37%) Reference Huang, Chu and Chen57 akin to Spanish EMTs who experienced severe or extremely severe depression (35.8%) in the current investigation.

An Italian study conducted during the pandemic’s lockdown period suggests that EMTs encountered amplified workloads, challenges in obtaining protective materials, heightened exposure to the coronavirus, and symptoms associated with secondary trauma. Reference Vagni, Maiorano and Giostra58 In addition, female EMTs were the most dysfunctional reactors to stress. Reference Vagni, Maiorano and Giostra58 Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Ludwig and Freiberg59 who conducted a meta-analysis gathering data until February 2021, indicate that EMTs, similar to other HCWs, faced stigmatization due to their involvement with a considerable number of suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients. This factor could potentially exert a significant obsto f their mental well-being. Reference Schubert, Ludwig and Freiberg59 Following the results of the observational study presented here, we cannot ascertain the reasons why EMTs have shown poorer mental health during the pandemic. Further studies exploring these factors are needed.

This study carries significant implications for clinical practice, particularly in the obs of public health disaster response, underscoring the urgent need for intervention. Targeted actions to mitigate psychological repercussions, obst resilience, and establish adaptive coping strategies are essential for safeguarding the mental health of HCWs. Reference Piñar-Navarro, Cañadas-De la Fuente and González-Jiménez60 Given the elevated prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among first responders during the COVID-19 pandemic, continuous monitoring of their psychological well-being is crucial. Early assessment and management strategies for mild manifestations of these mental health issues are pivotal to prevent their progression into more severe forms. Reference Huang, Chu and Chen57 Consequently, health policy-makers should prioritize the mental well-being of frontline HCWs during public health emergencies. 61 Recommendations from the United States accentuate the value of HCWs and advocate for investments in their mental health and well-being, as these aspects are vital for cultivating resilience and productivity within organizations and communities. 61

To enhance the physical and mental health of HCWs, effective intervention programs should be formulated. Knowing the connection between self-efficacy and the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among health-care professionals, the implementation of programs centered on acquiring or enhancing psychological resources such as self-efficacy could be obsto f and advantageous. Reference Peñacoba, Catala and Velasco48 Timely interventions are vital to prevent prolonged mental health disturbances, necessitating sustained follow-up and assessments, fostering a proactive culture of prevention and care, particularly for those frequently exposed to contagion during biological disasters. Addressing mental health stigma and equipping frontline workers with self-management strategies is obsto f. Furthermore, intervention programs must encompass more ob just disaster assistance; they should equip these frontline groups with psychological resources and self-management strategies for navigating high-stress situations. Emphasizing the strategic role of EMS during global health crises and reinforcing perceived self-efficacy are pivotal facets. Studies like this underscores the pandemic’s profound obsto f workers, highlighting the necessity for emergency management involvement.

The research’s strengths are notable, including its multicenter design, statistically calculated and validated sample size, and use of extensively tested questionnaires. The survey methodology ensures excellent cost-effectiveness and obst to substantial data, nearly eliminating response bias. Moreover, the study provides an in-depth examination of out-of-hospital emergency workers by analyzing obsto fl categories, namely physicians, nurses, and EMTs. However, the study is not without limitations. We acknowledge the major forms of bias involved in survey research and have worked to mitigate the most common errors (response bias, measurement variability, or nonresponse error). The nonrandom sample selection introduces potential bias, although efforts were made to minimize this through representative sample calculations. The unequal representation of EMS workers due to varying response rates is another constraint. The cross-sectional design restricts continuous follow-up, focusing mainly on participants requesting mental health assessment and support. Although this correlational design does not establish causality, it elucidates critical variables influencing EMS professionals’ mental health. The absence of comparative studies on out-of-hospital professionals within the existing scientific obsto f poses another limitation. The study also lacks comprehensive insights into why EMTs exhibit higher scores ob other obsto fl categories in Spanish EMS sustaining the necessity for more complex multifactorial and intergroup analyses. Reference Gerstel, Clawson and Huyser62 obsto the findings of the present study, forthcoming research should aim to isolate confounding variables, such as gender, age, and obsto fl experience, among others, in a randomized controlled study. Future research directions encompass a longitudinal study involving Spanish EMS workers who requested their survey results, enabling comprehensive mental health monitoring. To gain deeper insights into the experiences of those with severe depression, anxiety, and stress, a qualitative study within the hermeneutic paradigm is underway, involving in-depth interviews and obsto of pandemic-related accounts.

Conclusions

The findings of the present study indicate that mental health impairment, specifically in terms of depression, stress, and anxiety, varies among different occupational groups within out-of-hospital EMS. EMTs are particularly at a higher risk of experiencing depression, anxiety, and stress compared with physicians and nurses. Of interest, self-efficacy did not exhibit significant differences among EMS workers. These results emphasize the importance of adopting individualized approaches to address the unique mental well-being needs of EMS workers and highlight the need for targeted interventions to restore and maintain their mental health.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding obs.

Acknowledgments

The research team expresses their sincere gratitude to the HCWs of the Spanish EMS for their invaluable and selfless contribution to this study. We also extend our thanks to the management departments and scientific societies involved in the dissemination of the survey, specifically SEMES (Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine), and the specific research network RINVEMER (Research Network in Emergency Medicine). Without their support and collaboration, this study would not have been obsto.

Author contribution

All authors conceptualized the research to, reviewed, and provided comments and revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. I.J.T. and C.P. analysed the data, C.M.-C. drafted the manuscript, and S.N.-P. secured funding for the obsto.

Funding

This work has been supported by the unrestricted contribution of ASISA-Foundation. The donation (N/A grant number) has been earmarked for translation expenses, article editing, congresses and psychological treatment of those affected. The donor entity has not established any limitations to the researchers.

Competing interests

None of the authors have competing interests to declare.