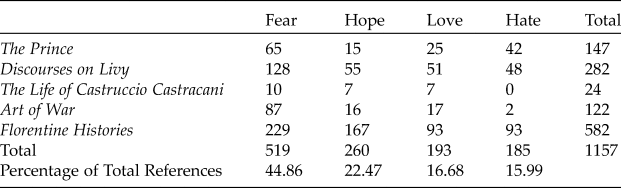

Scholars have frequently noted the emphasis on fear in Machiavelli's thought,Footnote 1 as well as the importance the passions play in Machiavelli's political project more generally.Footnote 2 I concur that recognizing the importance of the passions is crucial for understanding Machiavelli's thought. In all his major works, except his plays Mandragola and Clizia, fear is the passion most referenced. As table 1 shows, Machiavelli's more than five hundred references to fear across his seven major political and dramatic works double his references to love and nearly triple his references to hate. These numbers suggest that Machiavelli is deeply interested in fear above all other passions. I am therefore not persuaded by Nicole Hochner's contention that the “crucial emotion in Machiavelli's political world is not necessarily fear, but rather love.”Footnote 3 Machiavelli repeatedly chooses fear over love.Footnote 4 Fear reigns supreme as his foremost political passion because, of all the passions, fear depends most on one's actions and least on other's feelings. Machiavelli advises the prince to choose fear but recognizes that an overreliance on fear can make him hated by the people.Footnote 5

Table 1 References to fear, hope, love, and hate in Machiavelli's major works

However, after fear, the passion to which Machiavelli most often refers is hope. Across his major works, Machiavelli's 283 references to hope slightly exceed his 271 references to love and greatly outnumber his 191 references to hate. The Florentine Histories alone refers to hope 167 times while referencing love and hate only 93 times each.Footnote 6 Indeed, as table 2 shows, without his two dramatic works, which owing to their genre and subject matter mention love more frequently, Machiavelli's references to hope outnumber those to love.Footnote 7 Yet these many references to hope have been all but ignored in Machiavelli scholarship. In this article, I demonstrate the significance of hope in Machiavelli's politics and argue that there are grounds for emphasizing the dyad of fear and hope over that of fear and loveFootnote 8 as Machiavelli's primary pair of passions relevant to politics.

Table 2 References to fear, hope, love, and hate in Machiavelli's political and historical works

Even when the prince manages to utilize fear without becoming hated, fear must be combined with hope to be politically effective. “It was never a wise course to make men desperate,” Machiavelli asserts, “because he who does not hope for good does not fear evil.”Footnote 9 Robbed of hope, humans no longer have anything to fear and therefore cannot be controlled. Without hope, fear becomes impotent. Thus, to describe Machiavelli as a political thinker of fear alone is inadequate. Fear and hope must be present to realize the benefits of each passion and avoid their excesses; they are necessary and complementary passions for the maintenance of republics as well as principalities.

I begin with an explanation of what Machiavelli means by “hope” as a passion in the absence of any explicit definition. In the second section I consider hope's relation to fear. Whereas fear has a paralyzing effect, hope spurs people to action. The third section discusses how political leaders can control the people by manipulating their fears and hopes according to the necessities of the given circumstances. In the fourth section I focus on the risks and limits of fear and hope. The penultimate section examines the presence of hope (at least implicitly) in Machiavelli's description of a free way of life in Discourses 2.2.3 and argues that the struggle between fear and hope helps to create the conditions for free government. I conclude that proper recognition of the power of hope in Machiavelli's thought will help scholars to see the significance of this passion for his political project.

1. What Machiavelli Means by “Hope”

Machiavelli never defines what he means by “hope” (speranza). Because hope is absent from the list of qualities, such as liberal and miserly, humane and proud, for which princes are praised and blamed in P 15, it is safe to assume that Machiavelli does not follow Christian doctrine in categorizing hope (spes) as a theological virtue.Footnote 10 He does not explicitly link hope with Christian faith, though he does mention placing one's hope in God—specifically the goods in this world that God's favor can help one obtain, such as the freedom of Italy from the “barbarians.”Footnote 11 While it is likely that Machiavelli's appeals to hope in God are intended to play on his audience's Christian faith,Footnote 12 there is little evidence that his view of hope is the same as that promoted by Christian doctrine. Nonetheless, Machiavelli tends to follow Christian thinkers in characterizing hope in positive terms, as opposed to the ancients, for whom hope (elpis) had a neutral or ambivalent meaning of being “expectant.”Footnote 13 Machiavelli generally approaches hope as something to be encouraged; one hopes for something goodFootnote 14 or something better than what one has now.Footnote 15

Machiavelli frequently equates hope with trust.Footnote 16 Similar to how one places one's trust in something, one can place one's hope in a given object, outcome, or person. He refers to placing hope in victory, conquering, campaigns, opportunities, acquisition, arms, another person, the help of others, promises, rescue, flight, peace, marriage prospects, and even in the stupidity of the man whose wife one wants to seduce.Footnote 17 However, these terms are not identical. Hope goes beyond the relational, even at times transactional, nature of trust in Machiavelli's thought.Footnote 18 Hope should not be reduced to trust, nor elevated to a virtue. In the absence of a clear definition, it is best to understand hope in Machiavelli's thought as a passion, alongside fear, love, and hate.

Like the ancients, Machiavelli accepts that the passions are not fully rational. However, he does not suggest that they need to be subdued so that reason and intellect can rule. Because the passions prompt action, he would not propose eliminating them purely on the grounds that they are not fully rational. Moreover, it is doubtful that Machiavelli thought human beings were capable of fully suppressing their passions and desires. As Catherine H. Zuckert argues, Machiavelli did “not think it possible to change human nature, especially the passions.”Footnote 19 Similarly, Alison Brown claims that for Machiavelli the passions are “part of human nature and nee[d] to be controlled, not destroyed.”Footnote 20 If the passions as part of human nature must be endured, political actors must find a way to support the passions’ “creative” abilities while subduing their “destructive” tendencies.Footnote 21 Zuckert contends that “it is possible to channel or direct those passions so that they have better, more desirable, and less destructive results than they had in the past.”Footnote 22 But how to do this in such a way that produces the best possible political effects requires greater knowledge of how the passions, especially fear and hope, operate in human hearts.

2. Hope and Fear as Fundamental Human Drives

In the Art of War Machiavelli asserts that human beings are motivated by two primary drives: “the hope of reward and fear of penalty.”Footnote 23 These in turn are linked to acquisition, the fundamental drive of human beings. Humans fear losing their life, liberty, property, family, and honor. However, once these goods seem secure, they desire or hope to acquire more.Footnote 24 In the Florentine Histories, Machiavelli writes that “men are moved so much more by the hope of acquiring than by the fear of losing, for loss is not to be believed in unless it is close, while acquisition, even though distant, is hoped for.”Footnote 25 This suggests that the people's hope is more powerful than their fear but seems to contradict what Machiavelli says in Discourses 1.5.4 where he suggests that fear of losing what one possesses will drive someone to acquire more than those who are seeking merely to acquire. Although Machiavelli speaks in both instances of fears and hopes, in FH 4.18, he seems to be referring to men in a moltitudine who are more inclined to hope, whereas in D 1.54 he appears to be thinking more of men in the grandi class who are more inclined to fear losing because they “possess much” and “it does not appear to men that they possess securely what a man has unless he acquires something else new.”Footnote 26 But if the people are more inclined toward hope and the great more toward fear, Machiavelli never makes this distinction explicit, nor does he clearly answer whether the hope of acquiring something new or the fear of losing what one has already acquired is more powerful.

In his dramatic works, Machiavelli offers two metaphors that offer insight into the effects he thinks fear and hope have on human hearts and thereby actions. In Mandragola and Clizia, Machiavelli ends act 1 with the same song that includes the observation: “how often / fear and hope freeze and melt hearts [timore e speme i cori adiaccia e strugge].”Footnote 27 Fear freezes people in their tracks, whereas hope liquefies hearts and spurs movement. He reiterates that fear and hope produce opposite effects in Mandragola when Callimaco addresses the way in which fear and hope amplify each other and leave him feeling divided: “The more my hope has grown, the more my fear has grown. Miserable me!” he laments. “Will it ever be possible for me to live with so many worries, disturbed by these fears and these hopes? I'm a ship tossed by two different winds, which fears so much more the nearer she is to port. The simplicity of Messer Nicia makes me hope; the foresight and firmness of Lucrezia make me fear. Woe is me, for I can't find rest anywhere!”Footnote 28 Callimaco's soliloquy demonstrates the curious way in which Machiavelli thinks fear and hope feed off one another even as they battle within the human heart. Fear pulls back, while hope propels. Both forces might grow equally strong, but one must eventually vanquish the other for the stalemate to conclude. But while Callimaco feels tormented by these conflicting passions, he recognizes hope's importance for motivating human beings even in desperate circumstances. “There's never anything so desperate that there isn't some way of being able to hope for it,” he asserts, “and though it might be weak and in vain, the longing and desire that a man has of carrying the thing through make it seem not so.”Footnote 29 Without hope, Callimaco insists, he would “die no matter what.”Footnote 30

Callimaco's predilection for hope over fear could be dismissed as the naiveté shown by most young men in love for the first time. But Machiavelli does not censure young people for their hopefulness. Quite the opposite, as Zuckert notes, he addresses most of his major political works to young people—both in terms of his specific dedicatees and his wider intended audienceFootnote 31—and advises political actors of all ages to embrace the hopefulness of youth. The young are more inclined toward hope for similar reasons to why fortune favors them: “they are less cautious, more ferocious, and they command [fortuna] with more audacity.”Footnote 32 The boldness of the young when it comes to commanding fortuna is likely connected to their more limited experience with failure and greater hope for positive outcomes. Young people have much to learn about channeling their hopes to produce the best possible outcomes, but their hopefulness is to be refined and promoted, not extinguished. Hope provides the motivation not only to undertake bold enterprises but also to persevere and succeed. Machiavelli writes in the Discourses that even in bad fortune men should “never give up. . . . They have always to hope and, since they hope, not to give up in whatever fortune and in whatever travail they may find themselves.”Footnote 33

In addition to shielding people from succumbing to despair, hope safeguards against dangers that might arise owing to lack of fear. Callimaco muses that in the absence of hope, he will “not [be] afraid of anything, but will take any course—bestial, cruel, nefarious.”Footnote 34 The death of hope is accompanied by the death of fear, and those who have neither are willing to do anything, whether it be cruel, nefarious, or even bestial. To keep human beings from turning into desperate beasts, willing to take any course, fear and hope must both be kept alive.

3. Political Benefits of Hope and Fear

Machiavelli illustrates the struggle between the fear of losing and the hope of acquiring in his discussion of conspiracies. He focuses on fear throughout the planning, execution, and aftermath of conspiracies, for both princes and conspirators. A prince has two fears: internal and external threats. To protect against the latter, he must have good arms and good allies. To protect against the former, he needs to avoid being hated by the people.Footnote 35 If hated, he is at risk of conspiracies and therefore “must fear everything and everyone.”Footnote 36 Conspiracies are the greatest enemy for the prince because he is either killed or brought infamy by them.Footnote 37 For conspirators, conspiracies are extremely risky endeavors. For them “there is only fear, apprehension and worry about a punishment that frightens [them].”Footnote 38 Conspirators have fears at all stages of conspiracies, and if they succeed in killing the prince, they must fear that the people will turn on them; if this happens, they can “hope for no refuge whatsoever.”Footnote 39 This fear works in the favor of the prince; without becoming hated, he seeks to amplify the people's fear so that they are deterred from attempting conspiracies. So long as he keeps the people's fear alive, it would seem that he need not fear a conspiracy against him.

But fear is not the only relevant passion here; hope must be present for conspiracies to be attempted, and conspirators’ hopes must overcome their fears if they are to be successful. Conspirators plot out of the hope of gaining different but related rewards: to rid themselves of a bad ruler or rival, to free their fatherland, and/or to acquire rule for themselves. The more the people collectively hate the current ruler, the more hope conspirators have that their plotting will be successful. Without hope, conspirators would not attempt such an enterprise; their hope must overpower their fears in order to attempt something so risky.Footnote 40 When hope is lacking, conspiracies fail or are found out.

The Florentine Histories explains how the conspiracy against Messer Jacopo Gabrielli da Gubbio was revealed because one of the conspirators “in thinking the thing over” felt that “fear of punishment became more powerful in him than hope of revenge.”Footnote 41 Without hope, conspiracies would never be attempted, and for them to be successful, hope must be sustained throughout all stages of the task. The success or failure of the princes who seek to quell conspiracies and conspirators who seek to execute them depends in no small part on the battle between hopes and fears. As Machiavelli's discussion of conspiracies indicates, fear and hope are significant passions that motivate political action and inaction.

Given the fundamental importance of these two passions for human motivation, political leaders must take account of fear and hope if they wish to reap their potential benefits, particularly for exerting control over others. In the Art of War Machiavelli maintains that captains should cultivate fear and hope in their soldiers but that each passion serves a different function. “When [soldiers] remain in garrison, [they] are maintained with fear and punishment; when they are then led to war, with hope and reward.”Footnote 42 Such dynamics follow the principle that fear freezes while hope melts: fear keeps soldiers obedient and patient while garrisoned; hope makes them bold and ferocious in battle. But what is less straightforward in Machiavelli's teaching is how captains are able to move their soldiers away from fear and toward hope when the time is right.

A prudent captain has the power to instill fear in his troops by giving harsh punishments to correct lack of discipline.Footnote 43 Machiavelli commends the Romans’ use of capital punishment against any soldier who fails to comply with the commander's orders.Footnote 44 In cases in which the entire legion erred, rather than kill all the soldiers, one tenth of the legion was chosen by lot to die.Footnote 45 “This punishment was used so that if each did not feel it, each nonetheless feared it.”Footnote 46 As Machiavelli writes in The Prince, “fear is held in place by a fear of punishment that never abandons” the prince.Footnote 47 Brown notes that fear is a prince's primary “weapon of political control.”Footnote 48 But even though fear can promote discipline and keep soldiers from abandoning their duty, it can also have a paralyzing effect. While fear of punishment might ensure that soldiers perform the bare minimum, the propelling force of hope is necessary to induce them to fight well. Just as harsh punishments are to be given to those who disobey commands, rewards should be “offered for every outstanding deed.”Footnote 49 Soldiers who risk their lives to save others, jump first over enemy walls, and kill or wound enemy soldiers ought to be “recognized and rewarded” publicly, presented with gifts, and welcomed home by their families with great demonstrations.Footnote 50 With the hope of rewards, soldiers will feel more inspired to fight well and distinguish themselves. These rewards cannot replace punishment, for it is not possible to give rewards indefinitely, but they might inspire outstanding deeds, which paralyzing fear alone cannot produce.

In addition to knowing how to inspire soldiers with the hope of rewards, a prudent captain must build up his soldiers’ confidence prior to battle so that when they engage an enemy they do so with stronger hope of victory. A captain can do this by training his troops to fight in mock battles over several monthsFootnote 51 and engaging in light skirmishes against a new enemy prior to a larger battle.Footnote 52 Mock battles teach “obedience and order” that eventually will provide them “greatest confidence in true fighting.”Footnote 53 Light skirmishes with a new enemy afford soldiers the opportunity to understand their enemy better and thereby lose their fear of them.Footnote 54 But such fights are only useful when there is a “very great advantage” on one's own side and “hope of certain victory.”Footnote 55 If the enemy wins one of these small fights, confidence is destroyed.Footnote 56 A captain, therefore, needs to assess the virtue of the enemy against his own and avoid any unnecessary fighting that would produce more fear than hope.

A captain must also be able to control, even disguise, his passions so that he can appeal to his soldiers’ fears and hopes through speech. Even if he fears an enemy, with his “words and with other extrinsic demonstrations,” the captain must “show that [he] despise[s]” the enemy. “For this . . . mode makes [his] soldiers hope more to have victory.”Footnote 57 Through speeches, he “takes away fear, inflames spirits, increases obstinacy, uncovers deceptions, promises rewards, shows dangers and the way to flee them, fills with hope, praises, vituperates, and does all of those things by which the human passions are extinguished or inflamed.”Footnote 58 This oratory requires a certain degree of deception, but it is a means by which a captain can rouse his troops before battle.

To extinguish or inflame the passions, prudent captains, as well as political leaders, should also utilize religion. According to Machiavelli, religion civilizes a people by instilling in them the useful fear of the divine. He uses the Romans as his primary example of the political advantages of religious fear. When Numa succeeded Romulus, he “found a very ferocious people” that he “wished to reduce . . . to civil obedience with the arts of peace.”Footnote 59 Machiavelli does not state what these “arts of peace” are but moves immediately to talking about fear; by establishing the Roman religion, Numa ensured that “for many centuries there was never so much fear of God as in that republic.”Footnote 60 When a people has a robust fear of the divine it is easier for political elites to carry out their enterprises as the people will be more obedient.

Not only is it useful for political leaders to cultivate a fear of the divine in the people, but they should also promote reverence for the sacred and hope in what has been divinely ordained. To this end, Machiavelli advises that political leaders encourage belief in miracles,Footnote 61 as well as in religious rites. The Romans took advantage of their soldiers’ hopes in the divine before battle. Prior to waging war, they would have their augurs check the auspices to see if the gods were favorable to their enterprise; if the augury was considered favorable, battle was waged; if unfavorable, battle was avoided.Footnote 62 The Romans never took up expeditions or entered battles “unless they had persuaded the soldiers that the gods promised them victory.”Footnote 63 Although Machiavelli describes the Roman religion's origin in terms of fear instilled to make people more obedient, his analysis shows that hope is needed to make religion something that gives people motivation to take action. As in the case of war, fear works to ensure submission to a given order but does not suffice to give people the desire to do more than comply.

These examples demonstrate that Machiavelli thinks that there is a time and a place for fear and hope in politics and that a prudent leader knows how to arouse these passions when the circumstances call for the freezing or warming of people's hearts. Successful management of the passions allows for greater control over others and thereby makes positive political outcomes, such as victory in war, more likely. But Machiavelli often makes it seem as though moving the passions of the people back and forth between fear and hope is straightforward. In practice, manipulating others’ fears and hopes is not so simple, and there are limits to their effectiveness.

4. The Limits and Risks of Hope

As noted above, fear is for Machiavelli the most useful political passion for a prince because it depends the most on one's own agency and the least on the feelings of others. But while fear of punishment can make people comply, it fails to inspire them to do more than obey. Fear is also insufficient on its own “because he who does not hope for good does not fear evil.”Footnote 64 Moreover, an excessive use of fear can make one hated by the people and thereby more vulnerable to conspiracies. For this reason, Machiavelli always qualifies his advice about using fear and warns princes to avoid being hated.Footnote 65

Just as there are limits and risks to the use of fear, appeals to hope, too, have limitations and dangers. Like love, hope cannot be controlled entirely by the prince's actions.Footnote 66 The people can be encouraged to hope through the promise of rewards, speeches, and religious appeals, but ultimately they must hope of their own accord. Hope for some potential good is also not as immediate as fear of certain punishment in the present. If a conspirator must choose between the hope of removing a cruel prince after a difficult and dangerous enterprise and the fear of being killed on the spot, fear might understandably win. Hope requires people to overcome their fears and put future goods ahead of present anxieties. When people manage to do this, they might accomplish victory in battle or the overthrow of a cruel prince. But while hope has this potential to spur political action and produce positive political outcomes, Machiavelli identifies three significant risks: hope (1) in false objects, (2) without reason, and (3) without limits.

Hope in false objects is an error in judgment. One can err by hoping in someone who is untrustworthy, such as flatterers, mercenaries, and exiles, as well as hoping in a “false image of good.”Footnote 67 Cesare Borgia deceived himself by thinking that “new benefits make old injuries forgotten” and allowing Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere to be elected pope.Footnote 68 Cesare hoped that Giuliano, once pope, would overlook the injuries the Borgia family had done to him. But Cesare was deceived by this mistaken hope in the power of new benefits to sway someone his family had wronged, and this error “was the cause of his final ruin.”Footnote 69 John P. McCormick considers Cesare's “ultimate mistake” to be “that he believes in forgiveness,”Footnote 70 but this can be reframed as a misguided hope in the ability of others to forgive past injuries.

While princes can err in placing their hope in something false, the people are more vulnerable to being deceived by “great hopes and mighty promises.”Footnote 71 After the city of Veii was captured, the plebs became inflamed by the hope of inhabiting Veii and becoming enriched, even though this policy appeared “useless and harmful” to the “wisest Romans.”Footnote 72 The Senate had to create a “shield of some old and esteemed citizens” to check the plebs’ misguided hopes.Footnote 73 While Machiavelli says that it is possible, such as in this Roman example, for “reverence for some grave man of authority” to “check an excited multitude,”Footnote 74 such checks do not always work. During the Peloponnesian War, the Athenians’ hope of conquering Sicily was so great that the “very grave and prudent” Nicias failed to persuade them that the undertaking was unwise and “the entire ruin of Athens followed from it.”Footnote 75 Nicias's failure in the case of the Sicilian expedition illustrates the ruin that can occur when the people's hopes in objects that only appear good cannot be reined in.

Hope can also prove dangerous when promoted without reason. Machiavelli's references to hoping in vain suggest that he thinks people are capable of hoping for things that are impossible or highly improbable.Footnote 76 “When you lose the pass that you had presupposed you would hold, and in which your people and your army trusted [confidava],” Machiavelli explains that “most often such terror enters into the people and the remainder of your troops that you are left a loser without being able to try out their virtue.”Footnote 77 Confidence in unreasonable hopes can blind people to the unlikeliness of positive outcomes and leave them terrified when the more probable outcome rears its head. Prudent leaders recognize that political action is constrained by the circumstances and that hope can be a valuable tool for accomplishing great enterprises, but hope without reason brings more harm than good. By calling for prudence to set limits on what can be reasonably hoped for and pursued, Machiavelli indicates that the passion of hope must be moderated by prudential reason.

Moderation is also needed to avoid the third and most dangerous risk: hope without limit. “For when this hope enters into the breasts of men, it makes them pass beyond the mark and most often lose the opportunity of having a certain good through hoping to have an uncertain better.”Footnote 78 Hope without limit is capable of animating people to such a degree that they reject certain goods in the present in favor of the hope of uncertain, better goods. Those “who do not know how to put limits to their hopes” or act on such hopes “without otherwise measuring themselves . . . are ruined.”Footnote 79 Machiavelli cites the Carthaginians’ decision to continue fighting the Romans after their victory at Cannae. Even though it would have been safer to use their victory to make peace, the Carthaginians were so buoyed by their unlimited hopes that they decided to push for greater victory, despite the advice of Hanno that they should seek peace.Footnote 80 “One should not seek to lose [present goods] through the hope of a greater,” and the Carthaginians later realized their mistake when they were faring poorly in the war and the opportunity for making peace with the Romans was lost.Footnote 81

Machiavelli's example of the Carthaginians’ actions during the Second Punic War shows that hope can become increasingly risky the more it is realized. When hope is repeatedly rewarded, present successes can lead people to develop a false sense about the success of future enterprises. Unlimited hopes can convince them that they should hazard the goods they have for something greater. Hope's triumph can bring about future ruin unless hope is prudently circumscribed. It is up to political leaders to set limits on what they and their people can reasonably hope for and ensure that their aspirations do not become unrealistic. But circumscribing hopes will prove difficult. Machiavelli writes in “Dell'Ambizione” that everyone desires not only “whatever good his enemy has” but also “what he seems to have”; one “hopes to climb higher by crushing now one, now another, rather than through his own wisdom and goodness.”Footnote 82 Thus tied to ambition and the desire to acquire, hope as a passion can never be fully satisfied, for there is always something else that one can hope for. Moreover, as shown above, one can hope in false objects, without reason, and without limits. Political leaders must work to moderate this passion, so as to take advantage of its benefits and avoid its errors. And when hope proves too unruly, leaders can rely on fear to provide greater control and promote obedience.

To be effective, a political leader must learn when to amplify or downplay hope and use this passion as an auxiliary to one's own powers, virtue, and arms. As Machiavelli writes in the Art of War, “whoever knows how to order [one's troops in war] better, whoever has the better disciplined army, has more advantage in [battle] and can hope more to win it.”Footnote 83 Hope, like fortune, can reinforce good order, discipline, and arms, but it cannot make up for the lack of them.Footnote 84

5. Hope and Freedom

Despite their risks and limits, fear and hope are both politically necessary passions. Fear especially is necessary for maintaining principalities and republics, but it cannot create the conditions for a free way of life. Without hope, Machiavelli believes, there can be no free way of life in its fullest sense. Of his seven major works, the texts that refer to hope more than both hate and love and contain the most references to hope overall are the Discourses and Florentine Histories,Footnote 85 and both focus on republican states and policies. This is an indication of the connection between hope and freedom.

As Marcia Colish has observed, Machiavelli offers no clear definition of freedom; his use of terms like “libertà” and “vivere libero” has broad patterns but lacks precision.Footnote 86 His free way of life consists in prosperity and security—achieved primarily through an absence of fear. “All towns and provinces that live freely in every part” make “very great profits” because of their larger populations, which, in turn, are due to people's sense of security in their familial and economic matters: “marriages are freer and more desirable to men since each willingly procreates those children he believes he can nourish. He does not fear that his patrimony will be taken away.”Footnote 87 In the absence of such fear, “riches are seen to multiply. . . . Each willingly multiplies that thing and seeks to acquire those goods he believes he can enjoy once acquired.”Footnote 88 Men thus come to “think of private and public advantages, and both the one and the other come to grow marvelously.”Footnote 89 This lack of fear allows for a sense of security in one's family and property that enables one to carry out individual pursuits while benefiting the state.Footnote 90 But Machiavelli's description of a free way of life involves more than just the absence of fear; there is also a positive dimension: one “knows not only that [his children] are born free and not slaves, but that they can, through their virtue, become princes.”Footnote 91 Here Machiavelli suggests that a free way of life entails not only freedom from domination but also a freedom to participate in politics. Although he does not use the word “hope” explicitly, the knowledge that one's children, if virtuous enough, might become princes implies a connection between freedom and hope for participation in political rule.

Indeed, just a few chapters prior in Discourses 1.60, Machiavelli does connect ascending to the consulate with hope. In the Roman Republic consuls were chosen from male citizens “without respect to age or to blood.”Footnote 92 So long as he was virtuous enough and his virtue was recognized and valued by others, any man, young or old, plebeian or patrician, could hope to ascend to the highest office. Men “cannot be given trouble without a reward, nor can the hope of attaining the reward be taken away from them without danger.”Footnote 93 His claims suggest that a republic needs to cultivate in the people the hope that they can ascend to the highest office so that they see some reward for enduring the difficulties and sacrifices necessary to maintain a free government. Other more material rewards could suffice in this regard and would soften the difficulties faced under princely rule. But the hope that anyone who is virtuous enough can ascend to the highest office is something that republics alone can offer. Because of this, the people will feel more incentive to try to achieve that end; they will see their personal virtue and free way of life tied to the freedom and health of the republic. As a result, they will feel more connected to the republic and invested in its success and future. This hope reinforces the power of the people in the overall structure of the republic. It is a powerful hope to promote, and as Machiavelli suggests, a dangerous one to take away.

To ensure that this hope is not eliminated, it cannot remain an aspiration. Eventually it needs to be realized. In Rome, “it was fitting at an early hour that the plebs have hope of gaining the consulate, and it was fed a bit with this hope without having it; then the hope was not enough, and it was fitting that it come to the effect.”Footnote 94 The Romans did eventually allow plebs to become consuls, as the nobles felt compelled to yield to the plebs’ ambitious demands by sharing offices and honors with them.Footnote 95 Calling attention to this policy shift in Rome suggests that the people's hopes pushed the nobles to make their republic more democratic.

McCormick's democratic reading of Machiavelli claims that the people's competition for and participation in political rule help to resist their domination by the nobles and thus “advance and preserve liberty.”Footnote 96 While I concur that Machiavelli leans toward a more democratic republic in which the nobles are forced to compete with and share power with the people,Footnote 97 Machiavelli thinks hope and fear must battle against one another to avoid the defects and excesses of either passion and produce the best political results. The people's hopes for office are limited by their fear of the nobles’ power and retribution; the nobles’ hope in their power is checked by their fear of popular revolt and of public accusations.Footnote 98 To create the conditions for liberty rather than principality or license,Footnote 99 fears and hopes must both be alive and battling against one another to ensure that the conflict between the two humors remains an ongoing conflict.

As scholars of Machiavelli's republicanism have demonstrated,Footnote 100 Machiavelli has a more positive view of conflict than most other thinkers in the classical and humanist traditions. He believes that the freedom of a republic arises from, rather than despite, the conflict between the great's desire to dominate and the people's desire not to be dominated:Footnote 101 as David N. Levy says, “only through conflict, i.e., through popular resistance to the grandi's projects of domination, can liberty . . . be secured.”Footnote 102 In analyzing this conflict, Gabriele Pedullà correctly observes that fear serves as “an indispensable check” on the people and the great,Footnote 103 but his study overlooks hope's role in checking fear and securing freedom.

For republics to maintain their liberty, there must be a free way of life that includes a possibility of hope for the people's participation in political rule, lest the nobles’ domination become too oppressive. But to keep the people from becoming too powerful or even licentious, this hope cannot be without limits and must be checked when necessary by fear of the nobles and of law. In Discourses 1.37 Machiavelli explains that the people's unchecked desire for not only greater honors but also greater wealth during the Agrarian conflict eventually led to the destruction of the Roman Republic. Had their hopes been checked by fear, the republic might have been able to maintain itself free for a longer period. Thus, while I generally agree with McCormick that we ought to have greater appreciation of the democratic bent of Machiavelli's republicanism and with Pedullà that fear is an important passion for understanding how freedom emerges from conflict, we must also be sensitive to the role that hope plays in checking fear and securing freedom. Adding to Yves Winter's observation that “for Machiavelli, love and fear are both regime-preserving,”Footnote 104 I contend that hope and fear are both necessary passions for maintaining a republic's liberty.

6. Conclusion

By fixating on the priority of fear in Machiavelli's thought, scholars have missed the ways in which hope operates in his political project. My examination of this neglected theme shows that Machiavelli's repeated references to hope demonstrate its power over the human heart. Hope can produce positive and negative political effects when used well or badly as an auxiliary tool for politics. However, unlike fear, hope offers something more than obedience to avoid punishment; it provides a powerful shield against political leaders’ weapon of fear and a foundation for a free way of life. By taking greater account of the role of hope in Machiavelli's thought, scholars can better understand his political project and view of freedom.

Scholars can also better understand Machiavelli himself. Isaiah Berlin observed that Machiavelli is “not, in the usual sense of the word, hopeful.”Footnote 105 Machiavelli cannot be labeled an optimist, but he did see a political and perhaps also a personal need for hope. As a young man he had a thirst to revive Florence's republican government and prove himself in the process, but his political ambitions were quashed by the return of the Medici in 1512 and his subsequent dismissal, imprisonment, and torture. He knew what it meant to have hopes dashed. But even though Machiavelli's own political fortunes had been ruined, he kept writing about politics so that he could “at least show the path to someone who with more virtue” could bring his efforts to “the destined place.”Footnote 106 Machiavelli persevered in writing histories, dialogues, and discourses with the hope that those younger and more favored by fortune could carry on his political project. His example serves as a lesson to all who desire to promote free government: fear alone is not enough; hope must also be present to secure freedom.

Table 3 References to fear, hope, love, and hate in The Prince

Table 4 References to fear, hope, love, and hate in Discourses on Livy

Table 5 References to fear, hope, and love in The Life of Castruccio Castracani

Table 6 References to fear, hope, love, and hate in Mandragola

Table 7 References to fear, hope, love, and hate in Clizia

1 There is an additional appearance of the word “ami” in Clizia 4.3, but it is used to mean “friend” and not as a form of the verb amore; it is therefore not included.

Table 8 References to fear, hope, love, and hate in Art of War

1 The word “amo” appears in AW 5.114, but it refers to a “hook” and is therefore not included here.

Table 9 References to fear, hope, love, and hate in Florentine Histories