Our every action is a battle cry against imperialism, and a battle hymn for the people’s unity against the great enemy of mankind: the United States of America.Footnote 1

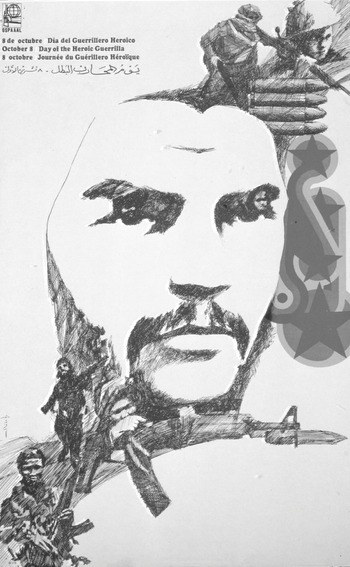

Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s message to the Havana meeting of the Organization of Solidarity with the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America (OSPAAAL) – also known as the Tricontinental Conference – was the clearest elucidation of his Tricontinental vision of revolutionary warfare. The speech lauded the Vietnamese people for their courageous struggle against US imperialism and called for the creation of many other Vietnams. Guevara’s conviction that the international proletariat shared a common enemy led him to promote a strategy for guerrilla warfare on the continents of what is now widely referred to as the “Global South.” Though the nomenclature took a while to catch up, this shift in the conceptual construct of the developing countries, from the “Third World” to the “Global South” tracked an evolving understanding of the ways in which the world was divided. Guevara, among others (Figure 10.1), came to believe that the most salient divisions were not between the capitalist and communist blocs, but between the Global North – the industrialized economic powers, including the Soviet Union and other highly developed economies of the Eastern bloc – and the Global South. The latter term was understood as including not only the peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America – in other words, the decolonizing world – but also the subject peoples within the industrialized countries, particularly African Americans in the United States.Footnote 2

Figure 10.1 Che Guevara’s death in 1967 affirmed his position as a global revolutionary icon. He became the most familiar face in a pantheon of Tricontinental martyrs that included Patrice Lumumba, Mehdi Ben Barka, and Amílcar Cabral. OSPAAAL posters memorialized these contemporaries while also drawing linkages to older revolutions with celebrations of Cuba’s José Martí and the Nicaraguan Augusto Sandino. OSPAAAL, Olivio Martinez, 1971. Offset, 54x33 cm.

Guevara’s views on this subject put him at odds with revolutionary Cuba’s superpower ally, the Soviet Union. Cuban leaders, particularly Fidel Castro, found themselves caught between conflicting strategies: to cultivate the solidarity of the developing world, with Cuba playing a leading role, and to develop an alliance with the Soviet Union as the only great power capable of protecting the Cuban Revolution against US aggression. While Castro struggled to balance on this tightrope of competing imperatives, over time Guevara became more outspoken in his criticism of the Soviet Union. This tendency is ironic in light of his earlier self-identification as a communist and the role he played in radicalizing the Cuban Revolution beyond the more moderate visions of noncommunist and anti-communist members of the 26th of July Movement.

This chapter traces the development of Guevara’s beliefs, ideas, and actions, particularly as they evolved within three unfolding and interrelated historical contexts: the shifting Cuban-Soviet alliance, the deterioration of relations with the United States as the Cuban Revolution confronted the realities and legacies of US imperialism, and the deepening yet ultimately quixotic quest for Third World solidarity. Guevara both embodied and foreshadowed a pattern that would play out elsewhere in the developing world – admiration and emulation of the Soviet Union, followed by disillusionment with the model on offer in Moscow and a shift toward emphasizing the commonalities and solidarities of the Third World. His internationalism, idealism, and optimism ultimately contributed to the failure of his Tricontinental revolutionary vision, as they led him to seriously underestimate the heightened appeal of nationalism among the peoples of the newly decolonizing states.

Becoming “el Che”

Born in 1928 in Argentina to a downwardly mobile family of aristocratic background, Ernesto Guevara de la Serna was raised in an atmosphere of intellectual and political debate. As a medical student at the University of Buenos Aires, he came into contact with militant communists and accompanied them to at least one communist youth meeting, where he witnessed the destructive sectarianism of Argentina’s radical left. These experiences compounded his innate skepticism and distrust of established authority, while inculcating disdain for the factionalism of Latin America’s communist parties. Though sympathetic to communism, he never became a formal member of the Argentine communist party or any other political party. Moreover, he criticized Latin America’s reformist left-wing parties for their anti-communism and amenability to cooperating with the United States. Guevara’s extensive travels around Latin America brought him face to face with the dreadful living conditions of poor peasants and urban workers in the countries he visited. He came to believe that the revolutionary struggle of “Nuestra América” was a shared one against US imperialism. Only by breaking Latin American dependence on the United States could the region truly decolonize and fulfill the promise of genuine freedom. Even at this early stage, Guevara’s outlook was international. He would repeatedly be frustrated by what he viewed as the parochial nationalism of many Latin American regimes and political parties.

In assessing the prospects for revolution in Latin America, Guevara was most impressed by Guatemala under Colonel Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán. The second democratically elected president in Guatemalan history, Arbenz came to power in 1951 and began to enact reforms that alienated powerful US interests and threatened the prerogatives of key sectors of Guatemalan society. Arbenz drew resentment not only from US business interests and domestic stakeholders but also from regional strongmen. The struggle between dictators and democrats in Central America and the Caribbean had been underway since before the end of World War II, with tyrants like Trujillo in the Dominican Republic and Somoza in Nicaragua conspiring to topple democratic reformers like Arbenz and his predecessor, Juan José Arévalo.Footnote 3 Guevara became steeped in the Guatemalan revolutionary milieu, embarking upon an intellectual journey into Marxism-Leninism with his soon-to-be wife Hilda Gadea, a Peruvian and member of the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance and the Alliance of Democratic Youth, the mass organization of the Guatemalan communist party, the Partido Guatemalteco del Trabajo (PGT).Footnote 4 Arbenz had recently legalized the party, and Guevara applauded Arbenz’s willingness to cooperate with communist leaders.Footnote 5 For Guevara, it was Arbenz’s willingness to work with the communists that distinguished him from other Latin American leaders who were leftist and reformist yet still anti-communist. Through the PGT, Guevara came into contact with exiled Cubans who were plotting a return to their home island to overthrow the increasingly tyrannical regime of Fulgencio Batista. Guevara was in Guatemala City when a ragtag band of exiles led by Colonel Castillo Armas and backed by the CIA, which coordinated a devastatingly effective psychological warfare campaign against Arbenz, launched a coup. The CIA’s propaganda, especially radio broadcasts, convinced Arbenz that a much larger army, including US troops, was on its way. He capitulated without firing a shot and fled to Mexico City.Footnote 6 This was a profound moment for Guevara, one that would shape his later attitudes and experiences. He had been fully prepared to fight on behalf of the Arbenz government, expecting the regime to arm the peasants and workers. Guevara was crushed when he found out that Arbenz had failed even to put up a fight.Footnote 7

Guevara’s assessment of the events in Guatemala tracked closely with that of the Guatemalan communists and Soviet officials. Nikolai Leonov, a KGB officer whose later career would include multiple stints in various Latin American countries and who served as an information officer at the Soviet embassy in Mexico City in the early 1950s, observed that across Latin America, opposition to authoritarian regimes was increasing. He predicted that because of US support for regional dictators, this opposition could potentially spill over into a general protest against the “imperialistic policies” of the United States.Footnote 8 Arbenz himself had sent an urgent plea to Moscow for help in rebuffing US imperialist pretensions. In a communiqué that was circulated in the International Department of the Soviet Communist Party (CPSU) Central Committee, Arbenz claimed that his economic policies, particularly agrarian reform, had threatened “such powerful monopolies as United Fruit,” which had then petitioned the Eisenhower administration to lend “moral and material” support to their invasion plans. The United States was waging a campaign of slander and lies, tarnishing Guatemala as a “threat to the security of the American continent” and a “bridgehead of international communism” in order to create a pretext for “open intervention” in Guatemala’s internal affairs, with the ulterior motive of depriving the country of its sovereignty and independence.Footnote 9

Though many Soviet officials and representatives of trade unions and other party organizations sympathized with Arbenz, the highest-ranking leadership in the CPSU still adhered to a more dogmatic view of revolution that characterized Guatemala under Arbenz as “bourgeois-democratic” because it was not led directly by the Guatemalan communist party. This rigid ideological orthodoxy undermined Soviet influence on Latin America’s radical left and pointed to a critical divergence from the views of Guevara, who understood that Arbenz’s attempts to cultivate a measure of independence by allowing the Guatemalan communist party to operate legally represented a clear break from US-imposed definitions of “hemispheric solidarity.” Soviet propagandists, based on information supplied by the communist parties and trade unions, assumed that the US intervention was designed to protect the monopoly status of United Fruit, and they discerned no difference between the interests of the Eisenhower administration and those of the company.Footnote 10 Guevara’s analysis of the Guatemalan coup was similar to that of Soviet officials, even though he had greater faith in Arbenz’s reforms. He believed that the US State Department and the United Fruit Company were virtually indistinguishable. The coup had proven that victory could only be gained through “blood and fire” and that the “total extermination” of the reactionaries was the only way to achieve justice in America.Footnote 11 This oversimplified view of US-Latin American relations would later contribute to Guevara’s unraveling in Bolivia.

Guevara’s experience in Guatemala shaped the development of his revolutionary strategy. Specifically, he learned three key lessons from the Guatemalan coup. First, given that factions of the armed forces had turned against Arbenz, it seemed obvious that for a revolution to consolidate its gains in the face of US imperialism and its local lackeys, the army needed to be purged and created anew. A revolutionary regime had no reason to expect the support of the existing armed forces. Second, the leaders of the revolution must arm the populace in order to defend the revolution. Guevara sincerely believed that if only Arbenz had provided weapons to his supporters in the labor unions and the peasantry, he could have vanquished Castillo Armas even without the help of the regularly constituted armed forces. Finally, the experience of Arbenz even more firmly convinced Guevara that US imperialism could only be defeated via armed violence.Footnote 12

After fleeing Guatemala, Guevara traveled to Mexico City, where he linked up with Fidel Castro and the Cuban exiles. They received training from Alberto Bayo, a Cuban-born Spanish military officer who had conducted guerrilla operations with the Republican forces in the Spanish Civil War. Bayo, whom Guevara later described as the only real teacher he ever had, counted among his influences Augusto César Sandino, who led the insurgency against the US occupation of Nicaragua from 1927 to 1933.Footnote 13 Sandino’s guerrilla strategy attacked the morale of US combat forces as well as the American public’s will to fight. From his mountain outposts, he spread the struggle into the cities, protracting the conflict and refusing to engage US troops head on.Footnote 14 Bayo also borrowed heavily from the consummate theorist of guerrilla warfare, Mao Zedong, though there were profound differences between the two. Mao’s strategy was aimed at a foreign aggressor; Bayo’s aimed instead at a domestic authoritarian regime. Mao’s strategy combined conventional with irregular warfare, whereas Bayo advocated an entirely guerrilla campaign on the Sandino model. The two agreed on the crucial importance of cultivating the active support of the local peasantry. For Bayo, success in guerrilla warfare could be achieved only when “a people suffer, whether from foreign invasion, the imposition of a dictatorship, the existence of a government which is an enemy to the people, an oligarchic regime, etc.” If such conditions were lacking, Bayo asserted, “the guerrilla war will always be defeated.”Footnote 15 Holding the United States responsible for installing and supporting regimes that caused so much suffering in Latin America, Guevara left Mexico dedicated to applying Bayo’s strategies to the “armed struggle against Yankee imperialism” in Cuba.Footnote 16

The Vanguard of the Latin American Revolution

Though the voyage and landing of the Granma was an utter disaster, the Castro brothers, Guevara, and several others survived and escaped into the Sierra Maestra mountains, where they waged guerrilla warfare against Batista’s forces for almost three years. Relations between the leaders of the urban underground and the leaders of the rural insurgency were tense at best, especially as Castro moved to consolidate his control over revolutionary strategy and tactics. Perhaps in large part due to the dispute between the urban and rural revolutionaries, Guevara assigned insufficient importance to the urban struggle in his theoretical writings on guerrilla warfare. The foco theory attributed to Guevara was popularized by Regis Debray, who oversimplified much of Guevara’s writings on revolutionary warfare.Footnote 17

Almost immediately upon consolidating power in Cuba, the revolutionaries of Castro’s 26th of July Movement began to look outward. Guevara, as one of the movement’s most committed internationalists, played a key role in planning for the earliest expeditions to spread the revolution to Cuba’s neighbors, especially those governed by brutal dictators like Somoza in Nicaragua and Trujillo in the Dominican Republic. These expeditions were motivated by ideological revolutionary romanticism as well as pragmatic security concerns. The Cubans sought not only to liberate their neighbors suffering under the tyranny of dictatorships but also to create a regional environment conducive to the consolidation of their own revolution.Footnote 18 Though all expeditions were either aborted or ended in spectacular failure, they demonstrated the regional outlook of the Cuban Revolution.

In June 1959, Guevara was dispatched on a tour of African and Asian states, many of which had been represented at the first Afro-Asian conference in Bandung in 1955. He also spent a week in Yugoslavia, his first visit to a socialist country. Although he found his trip fascinating, he was skeptical of the regime’s commitment to communism and frustrated by its refusal to grant a Cuban request for an arms deal.Footnote 19 Though raising some doubts about the socialist world, his travels solidified an ambition to unite the struggles of the peoples of all three continents – Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Che sensed that he was living at a crucial juncture in world history, when “the liberated people are becoming conscious of the great deceit they have been subjected to, the so-called racial inferiority.” Cuba’s identification with the Third World and integration into what would become known as the Non-Aligned Movement was, for Che, “the result of the historic convergence of all oppressed peoples.” The Cuban Revolution could be a catalyst for this convergence. Upon returning to Cuba from his travels around Africa and Asia, Che declared that “our continents will unite and destroy, once and for all, the anachronistic presence of colonialism.”Footnote 20

Guevara believed this global revolution would be summoned through armed violence and would result in a structural economic reordering in favor of small, postcolonial states, with Cuba serving as a model for both. In extrapolating the experience of the Cuban Revolution outward, Che acknowledged the existence of very few “exceptional” factors in the success of the revolution. The most important was that “North American imperialism was disoriented and unable to measure the true depth of the Cuban Revolution.” Future insurrections would not be able to count on such disorientation because “imperialism … learns from its mistakes.”Footnote 21 Yet Guevara remained confident of the hemisphere’s revolutionary prospects, because there existed, as Bayo had argued, common plights motivating the “colonial, semicolonial, or dependent” countries toward revolution. The “underdeveloped” world suffered from “distorted development” due to imperialist policies that encouraged raw material production and monocultural economies. Dependence on a single product, with a single market, was the result of “imperialist economic domination.”Footnote 22 In Cuba, the most basic fact of the economy was that it “was developed as a sugar factory of the United States.”Footnote 23 The revolution had been waged not merely to topple Batista but to reorder such unequal economic relations.

As head of the Department of Industrialization within the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INRA) and then as president of the National Bank, Guevara further developed his ideas about economic planning. Although his thinking was deeply influenced by Marxism-Leninism, he ultimately came to reject the economic prescriptions of the Soviet Union and other socialist states in Eastern Europe. He believed that the Soviet system had failed to advance the consciousness of the workers that was a prerequisite for the construction of genuine socialism.Footnote 24 Even before visiting the Soviet Union, he had read Soviet industrial manuals that referred to the law of value, which for Marx was at the center of the capitalist mode of production. The Soviet Union, in attempting to build communism from a pre-capitalist level of development, relied on the law of value, and hence the profit motive, to achieve efficiencies and thereby accelerate the development of productive forces. Guevara rejected this Soviet solution to the dilemma of industrialization, which he argued merely adopted the tools of capitalism but without the efficiency of the “free market.”Footnote 25 He further argued that the law of value should never operate in trade between the countries of the socialist bloc.Footnote 26 Specifically, he objected to the use of material incentives for production, maintaining that they must be replaced by moral incentives in order to undermine the law of value and achieve a truly socialist consciousness.Footnote 27 This idea would form one of the main planks in his critique of Soviet economic policy toward the developing world.

In August 1961, a special meeting of the Inter-American Economic and Social Council of the Organization of American States in Punta del Este, Uruguay, provided an ideal venue for Che to expound upon his economic ideas. First of all, he argued that economic planning was not possible until political power was in “the hands of the working class.” Second, the “imperialistic monopolies” must be “completely eliminated.” Finally, the “basic activities of production” must be “controlled by the state.” Only if those three preconditions held could real economic planning for development begin.Footnote 28 Che’s policies stood in stark contrast to the terms of the Alliance for Progress as presented by Kennedy administration officials at Punta del Este. Whereas the Alliance for Progress apportioned financial aid in the hopes of spurring moderate political and economic reforms, Che envisioned a revolutionary restructuring of the historically unequal economic relations across the Americas. He believed that it was necessary to protect Latin American businesses from foreign monopolies and that the United States must reduce tariffs on the industrial products of Latin American states. Furthermore, any foreign investment should be indirect and not subject to political conditions that discriminated against state enterprises. The interest rates on development loans should not exceed 3 percent, and the amortization period should be no less than ten years, with the possibility of extension in the case of balance of payments issues. Che also called for reforms to lighten the tax burden on the working class.Footnote 29 Additionally, he urged the US delegation to cease pressuring OAS member states not to trade with the socialist bloc.Footnote 30 As head of the Cuban delegation to the meeting, Guevara refused to sign onto the Alliance for Progress, arguing that it completely neglected the fundamental economic problems facing Latin America.Footnote 31

At the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in Geneva in 1964, Che continued to develop his economic platform. He declared that the “only solution” to the problems of humanity was to bring an end to the “exploitation of the dependent countries by the developed capitalist countries.”Footnote 32 Noting that the “socialist camp” had “developed uninterruptedly” at rates of growth much higher than its capitalist counterpart, he lamented the “total stagnation” of the underdeveloped world.Footnote 33 In Guevara’s view, this stagnation was a direct legacy of colonialism, and the decisive defeat of the imperialists was a necessary precondition for economic development.Footnote 34 Though the vast majority of his ire was reserved for the United States, by placing the socialist bloc within the developed world and counterposing the developed world with the decolonizing countries, Guevara gestured toward a different understanding of economic exploitation from the one offered by the Soviet Union. Guevara’s views on this issue were more closely aligned with those of the Chinese communists in positioning anti-imperialism – as opposed to class conflict – at the center of the struggle for economic liberation.

Between the Third World and the Soviet Union

From the outset, Cuban leaders positioned the revolution between the Third World and the Soviet Union. A combination of ideological convictions, geopolitical realities, and domestic political pressures conditioned early Cuban foreign policy. Castro sought to consolidate power in his hands domestically, using the Cuban communist party’s ties to Moscow to court the Soviet Union while simultaneously seeking to export the revolution to Cuba’s authoritarian neighbors in a bid to shore up regional security. In the looming confrontation with the United States, it was critical that Cuba’s neighbors not become a convenient launching point for a US invasion. Yet these oft-conflicting imperatives required a careful balancing act. Castro could announce his intentions to establish an alliance with the Soviets only once the more moderate factions of the revolutionary movement had been sidelined or eliminated. At the same time, the Cubans had to send reassuring signals to Moscow regarding the strictly tactical nature of their temporary compromises with the national bourgeoisie.Footnote 35

Castro repeatedly urged greater unity and emphasized the power of Cuba’s revolutionary example for the rest of Latin America.Footnote 36 In a speech at the UN, Castro declared that the “case of Cuba” is the “case of all underdeveloped, colonialized countries.”Footnote 37 At the same time, the Cubans were embarking upon what would ultimately become a highly contentious relationship with the Soviet Union. In March and April 1959, Cuban emissaries began making overtures; one emissary told the Soviet ambassador to Mexico that the Castro regime was striving to emulate the accomplishments of the Soviets and that the restoration of formal diplomatic relations between the two countries was “only a matter of time.”Footnote 38 It was not long, however, before Cuba’s efforts to export the revolution created tensions between the Soviet Union and countries in Latin America. Mexican officials expressed their disapproval of Cuban expeditions in the Caribbean to the Soviet ambassador in Mexico City in August 1959. The Mexican government had detained and deported three separate groups of Cubans who had been captured in Mexican territorial waters.Footnote 39 The Soviets had no interest in destabilizing the Mexican government, but they approached the Cuban Revolution with cautious optimism. The visit of Anastas Mikoyan to Havana in February 1960 to open the Soviet cultural and technical exhibit presented an opportunity for Moscow to evaluate the “character and path” of the Cuban Revolution and the possibilities for further Soviet-Cuban cooperation.Footnote 40

In October 1960, Che headed the first official Cuban delegation to the Soviet Union. His travels around the socialist bloc left his admiration for the Bolshevik revolution intact, but he also witnessed a clash between Soviet plans and Cuban revolutionary ambitions. According to Anatoly Dobrynin, Che requested Soviet assistance in constructing a steel mill and an automobile factory in Cuba in order to spur the industrialization of the economy. He was informed that what the Cuban economy really needed was hard currency and that the best way to obtain it was through continued sales of sugar.Footnote 41 Due in part to the continued operation of the law of value in intra-socialist bloc trade relations, as well as the Soviet prioritization of raw material imports over industrialization in its economic relations with Cuba, Che ultimately came to believe that the Soviet Union was complicit in the continued exploitation of decolonizing states.Footnote 42

Yet the Cubans needed the support of a great power patron like the Soviet Union in their confrontation with US imperialism. The case of Arbenz’s Guatemala seemingly proved that this confrontation would inevitably involve violence. Cuban leaders therefore sought to safeguard the security of the revolution by strengthening ties with the socialist bloc and the non-aligned world. Though Cuban ambitions most closely paralleled those of Third World radicals, only the Soviets and their Eastern European allies had the financial, industrial, and military resources that Cuba needed. This balancing act created tensions with Soviet leaders, who occasionally chastised the Cubans for their “revolutionary adventurism,” while some members of the Non-Aligned Movement viewed the Cubans as aligned with the communist bloc.Footnote 43 After the Bay of Pigs debacle of April 1961, which confirmed for the Soviets the fundamental inability of the United States to coexist peacefully with the Cuban Revolution, Havana amplified its requests for Soviet military assistance.Footnote 44

Fortunately for Castro, Cuban requests came at a time when Khrushchev was pursuing a more active approach to spreading Soviet influence in the decolonizing world. At the 22nd CPSU Congress in October 1961, Khrushchev lauded the “revolutionary struggle” of the peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, expressing his conviction that “the 1960s will go down in history as the years of the complete disintegration of the colonial system.” Yet “remnants” of the colonial system remained; Khrushchev singled out “the Guantanamo military base on Cuban soil,” occupied by the imperialists “against the will of the Cuban people.” The Soviet Union was “unswervingly fulfilling its internationalist duty.”Footnote 45 Khrushchev backed up this rhetoric with the provision of military aid to Cuba, including medium-range ballistic missiles capable of reaching targets in the United States and in some Latin American capitals.

These missiles would open a divide between the Soviets and their revolutionary clients during the October Crisis, more familiar as the Cuban Missile Crisis in Washington and the Caribbean Crisis in Moscow.Footnote 46 The idea of installing missiles in Cuba originated with Khrushchev, and some Soviet officials were skeptical that Castro would accept the deal, as it contradicted his identification of Cuba with the non-aligned world. The Cubans believed that the Soviet provision of nuclear weapons could protect the revolution from US aggression while enhancing the strategic position of the entire socialist bloc. Yet during the crisis itself, when Castro urged Khrushchev to consider launching the weapons in the event of a direct US invasion of Cuba, the Soviet premier balked. Khrushchev’s failure even to consult the Cubans regarding negotiations with the Kennedy administration infuriated Havana and ushered in a chilly period of Soviet-Cuban relations.Footnote 47 Mao was quick to capitalize on Khrushchev’s “great power chauvinism,” accusing the Soviets of kowtowing to the imperialists and selling out the Cuban Revolution.Footnote 48 After blinking into the nuclear abyss, the Soviets actively sought to reduce tensions with the United States, and Chinese hostility escalated to the point of considering Soviet influence as akin to a second form of imperialism.Footnote 49

Despite the greater ideological affinity of the Cubans with the Chinese, Havana was still dependent on Soviet aid, requiring Cuban leaders to continue their balancing act. The November 1964 conference of Latin American communist parties hosted in Havana illustrated one such compromise with Moscow. Although Beijing-oriented regional communist parties were excluded from the gathering, the delegates proclaimed support for the armed struggle in several Latin American countries – Colombia, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Panama, Paraguay, and Venezuela – while continuing to pursue the peaceful path to power in the rest of the region.Footnote 50 Mao was reportedly furious about the conference; he railed against the “three demons” of “imperialism, the atomic bomb, and revisionism,” with the Soviet Union epitomizing the last of these.Footnote 51 The goal was clearly to discredit the predominantly white, industrially advanced Soviet Union in the eyes of the Third World, but Guevara seemed to reject the political implications of this “theory of the two imperialisms.” The Soviet Union was reliably anti-imperialist and played an invaluable role in sustaining Cuba in a hostile region, he believed, even if Cuban and Soviet priorities did not fully align in terms of economics, the transition to socialism, and support for armed revolutionary movements.

Though Cuba did not abandon its Soviet patron, Guevara critiqued the communist superpower for what he saw as its divergence from the revolutionary path. While celebrating the anniversary of the Russian Revolution in Moscow in November 1964, he criticized the Soviet model of industrial success before a crowd of local students, suggesting that the “Soviet Man” was not so very different from, for instance, a Yankee. This assertion reflected his belief that the continued operation of the law of value would perpetuate a capitalist consciousness and thereby prevent the emergence of a fundamentally new socialist outlook. The students, recognizing this opinion as an attack from the left, accused him of “Trotskyism.” Che rejected the epithet.Footnote 52 But upon his return to Cuba, he indulged in a lengthy attack on the notion of “goulash communism,” arguing that the reason the socialist bloc was falling behind the West was not because it was following the tenets of Marxism-Leninism but because it had abandoned them. The Soviets had succumbed to the law of value and adopted all manner of capitalist methods.Footnote 53 Many in the Cuban leadership, however, did not share Guevara’s views and sometimes criticized his extreme ideological purity.

The following month, Guevara departed for a three-month tour of several African countries and China, where he continued this line of attack. At the second economic seminar of Afro-Asian Solidarity, held in Algiers in February 1965, Che criticized the Soviets as “accomplices” of the West in the exploitation of the underdeveloped world, and he asserted that the socialist countries had a “moral duty to liquidate their tacit complicity with the exploiting countries of the West.” He urged the socialist bloc to use its power to transform international economic relations.Footnote 54 At the heart of the matter was Che’s belief that ongoing, global revolution was necessary if small states like Cuba were ever to attain true political and economic independence. Though less racialized, this theory of Third World revolution aligned with much of China’s rhetoric and created tensions with the countries of the socialist bloc. Raul Castro, in an effort to patch things up, privately suggested to at least one Eastern European diplomat that Che’s proposals were “too extreme.”Footnote 55 Nevertheless, Guevara would soon avail himself of the opportunity to back up his rhetorical exhortations to tricontinental solidarity with meaningful action, as he turned his sights to the ongoing struggle in Africa for liberation from European colonialism.

The Cuban Vision of Global Revolution

Guevara believed that a global revolution was necessary to achieve a socialist transformation of the international system. Obtaining power via armed force was an essential prerequisite for eliminating the continuing vestiges of imperialism and transforming global economic relations. The spread of armed revolts would inevitably weaken the United States as it aided reactionary governments and became directly involved in counterinsurgency. Though the Cubans came to power with ambitions of fomenting revolution in the Americas, Africa seemed more fertile ground after a wave of decolonization swept the continent in the early 1960s. While Che’s erstwhile adventures in the Congo proved frustrating, the 1966 Tricontinental Conference helped establish a shared Third World vision of socialist revolution that would provide the impetus for new insurgencies in Latin America.

The Cuban revolutionaries exhibited an early and intense interest in the African liberation movements, particularly in the struggle of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) against French colonialism. As Piero Gleijeses has shown, “Algeria was Cuba’s first love in Africa,” and exchanges of weapons and medical assistance began as early as December 1961.Footnote 56 These exchanges demonstrated just how quickly the Cuban regime acted upon its vision of global revolution. Connections between Cuba and Africa stretched beyond material interests. Intellectually, the Cuban leadership – particularly Che – was profoundly influenced by Frantz Fanon, the radical psychologist and FLN member of French West Indian descent, whose philosophical writings continue to inform postcolonial studies. One can note striking similarities in the views of the two revolutionary thinkers. They both viewed the world in Manichean terms and disdained the national bourgeoisie that served as handmaidens to Western imperialism. Neither saw the possibility or even desirability of rapprochement with the capitalist world. Perhaps most importantly, both men were humanists; they emphasized the commonalities linking oppressed peoples everywhere and sought to build solidarity by transcending the class, racial, ethnic, religious, and sectarian divides that have long plagued humankind.Footnote 57 They believed this could happen only if a people’s national consciousness evolved to a higher level – that of “a common cause, of a national destiny, and of a collective history.”Footnote 58 They shared an emphasis on the tricontinental nature of the revolutionary struggle, and both believed that in order to build a new society, the structures of the colonial system must be destroyed and a new consciousness created.

As for how the countries of the Third World should conduct themselves in an international system divided between capitalism and socialism, Fanon and Guevara agreed: “The Third World ought not to be content to define itself in the terms of values which have preceded it. On the contrary, the underdeveloped countries ought to do their utmost to find their own particular values and methods and a style which shall be peculiar to them.”Footnote 59 Che held a deeper respect for communism than did Fanon, but he agreed that the Soviet model did not fit seamlessly with the conditions of Latin America and Africa. For him, it was impossible “to realize socialism with the aid of the worn-out weapons left by capitalism” because the “economic base has undermined the development of consciousness.” In order “to construct communism simultaneously with the material base of our society, we must create a new man.” Che sought a merger of socialism and Third World internationalism, wherein the mobilization of the masses would be achieved by moral rather than material incentives.Footnote 60 Indeed, for Che, the “ultimate and most important revolutionary ambition” was “to see man liberated from his alienation,” a theme common to Third World theorists.Footnote 61 Both Fanon and Che argued that their parties would be the vanguard. They rejected the necessity of waiting for the “objective conditions” of a revolution to ripen and argued that such conditions could be created by revolutionary movements. “Africa will not be free through the mechanical development of material forces,” Fanon wrote in 1960, “but it is the hand of the African and his brain that will set into motion and implement the dialectics of the liberation of the continent.”Footnote 62

If Algeria offered the first concrete example of solidarity, then the Congo became the prime illustration of why such cooperation was needed, especially after the 1961 assassination of Patrice Lumumba. Many progressives and socialists around the world viewed Lumumba as a symbol of the anti-imperialist struggle, and many Cubans interpreted his assassination as evidence that the forces of imperialism would not relinquish power without a fight. Though Che blamed Lumumba’s murder on the “imperialists,” he acknowledged that the Congolese prime minister had made some mistakes. He put too much trust in the United Nations and international law and failed to understand that the imperialists could be defeated only via force of arms.Footnote 63 Guevara would go on to lead an advisory mission to the Congo in support of Congolese revolutionary Laurent Kabila. In order to blend in with the Africans, the mission was composed overwhelmingly of Afro-Cubans, including Che’s second-in-command, Víctor Dreke.Footnote 64

Guevara’s dream of a Cuban-aided African revolution would not be realized until after his death. Although the Cubans were successful in infiltrating 150 men into eastern Congo in early 1965, they found Kabila’s forces undisciplined, surprisingly small in number, and divided along ethnic and political lines. There was little sense of shared struggle or will to coordinate forces. Though Che tried to instill the lessons of the Cuban guerrilla experience, he found students inattentive and overly attached to superstitions he perceived as limiting their interest in training.Footnote 65 With more Cuban instructors than recruits, Che left the Congo before the year was out.Footnote 66 The only bright spot in this “history of a failure” was that Che made contact with Agostinho Neto, leader of the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA).Footnote 67 Neto requested instructors, weapons, and equipment to train and arm MPLA cadres and showed interest in fighting alongside experienced Cuban guerrillas.Footnote 68 In agreeing to these requests, Guevara unknowingly laid the groundwork for the later Cuban military intervention in the Angolan Civil War, which pitted the MPLA against US-backed anti-communist forces after the country’s independence in 1975. At the height of Cuban involvement in sub-Saharan Africa in the 1980s, nearly 40,000 Cuban combat troops actively protected the MPLA from both domestic foes and the neighboring South African military. The psychological and material costs of this war contributed to the ultimate collapse of apartheid.Footnote 69

Guevara’s failure in the Congo did not blunt the Cuban commitment to revolution. Though Che was the most vocal proponent of guerrilla tactics, much of the Cuban leadership shared his belief that only revolution on a global scale would transform the international system and that Cuba functioned as the vanguard for this global revolution. This was the motivation for the Castro regime to work together with Algeria’s Ahmed Ben Bella (until his ousting in mid-1965) to organize the first Tricontinental Conference, convened in Havana in January 1966. The conference sought to define and organize a tricontinental revolution by integrating the “two great contemporary currents of the World Revolution” – the Soviet-led socialist revolution and the “parallel current of the revolution for national liberation.”Footnote 70 The goal, then, was to bridge the ideological differences that fueled the Sino-Soviet split, replacing it with revolutionary unity on the Cuban model. Accordingly, Castro openly criticized the Chinese leadership in his remarks, even as the general commitment to armed struggle adopted elements of the more aggressive Maoist approach to revolution that made the Soviets uneasy.Footnote 71 The peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, the conference collectively concluded, “must answer imperialist violence with revolutionary violence.”Footnote 72 This was the type of revolutionary syncretism, drawing on a wide base of support from the Second and Third Worlds, that informed the Cuban model of revolution, which Che was attempting to export.

Still abroad weighing his next move after the Congo debacle, Guevara’s absence was notable, but the message he sent epitomized his vision of Tricontinental unity. Disunity hobbled Kabila’s Congolese revolution, and it had undermined the prospects for global revolution. As the Soviet Union, China, and the nations of the Third World squabbled in the years preceding the Tricontinental Conference, the United States deployed troops in the Dominican Republic and South Vietnam. Would-be revolutionaries had to recognize that “Yankee imperialism” – the “fortress of colonialism and neocolonialism” as the Cubans described it – represented the “greatest enemy of world peace” and constituted “public enemy number one of all the peoples of the world.”Footnote 73 Che argued that resistance to the United States was the locus of unity for the struggles of the world’s downcast. Those on the frontlines of the struggle required the support of both the Third World and the socialist countries – what he and others referred to as the “progressive forces of the world.” Specifically, he lamented the “sad reality” that Vietnam “is tragically alone,” putting most of the blame for the plight of the Vietnamese people on the shoulders of US imperialism but also condemning those “who hesitated to make Vietnam an inviolable part of the socialist world.” The Tricontinental strategy aimed at the complete destruction of imperialism and the creation of truly independent nations, but to achieve this goal, progressive governments had to encourage and support those actively fighting against the United States and its capitalist allies; there had to be “two, three … many Vietnams.”Footnote 74

The conference established the Latin American Solidarity Organization (OLAS), which was to be permanently headquartered in Havana. Castro used the August 1967 OLAS conference to snub the Soviets, ensuring that most delegations were headed by noncommunist revolutionary leaders and issuing provocative statements that were clearly aimed at Moscow. In his closing speech, Castro criticized those who suggested the possibility of a peaceful transition to socialism and asserted that armed violence was the irrevocable course of the revolution in Latin America.Footnote 75

The Ill-Fated Bolivian Adventure

Guevara chose Bolivia to launch the continental campaign because he viewed it as ripe for revolution. In 1964, General René Barrientos had staged a coup against President Víctor Paz Estenssoro of the leftist Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario (MNR). Víctor Paz had come to power in 1952 after an insurrection of armed tin miners, Indian peasants, and labor unionists forced a reluctant military to honor his democratic election two years prior. Guevara, who had visited the country in 1953, believed that the MNR was insufficiently radical, even though Víctor Paz had enacted meaningful agrarian reform, nationalized the tin mining companies, and granted universal suffrage.Footnote 76 After the coup, Barrientos pledged to continue these reforms but kept the peace through increasingly repressive measures, alienating key rural constituencies from the government in La Paz.

Rising political frustration combined with several other factors to make revolution seem feasible. First, Guevara believed that the Bolivian army and security forces were too small and weak to effectively confront a guerrilla challenge. Second, he believed that the United States would be slow to react to an insurgency there, despite evidence of intense US interest in Bolivia in the framework of the Alliance for Progress.Footnote 77 Guevara seemed to hope that that the foco would inspire others throughout South America, so that if the United States did intervene, it would sink into a quagmire. Third, the geographical location of the country in the heart of South America was seen as a strategic center from which the revolution could spread. Fourth, Mario Monje, General Secretary of the Bolivian Communist Party, agreed to provide logistical support, contacts, and cadres to the effort.Footnote 78 Finally, the political circumstances of Bolivia’s neighbors were not viewed as favorable. Though Che initially hoped to launch a foco in his homeland under the command of his friend and fellow Argentine Jorge Masetti, the column was destroyed by the harsh climate of northern Argentina, its inability to attract local support, and ruthless Argentine security forces. Neighboring Peru, meanwhile, boasted a popularly elected civilian government that was embarking upon a program of moderately progressive reforms and an army that had effectively suppressed several guerrilla insurgencies in the two years before Che set out for Bolivia.Footnote 79

From the outset, though, Che found the conditions for revolution had been greatly exaggerated. At the Tricontinental Conference, Monje, as head of the Bolivian delegation, deceived the Cubans about the revolutionary potential of Bolivia and about the Bolivian Communist Party’s own intentions to launch a guerrilla foco. Bolivia’s communist left had split into two factions, with Monje’s Bolivian Communist Party remaining loyal to Moscow and the New Bolivian Communist Party aligning with Beijing. Moreover, the majority of Bolivian Marxists identified with neither of these parties, but instead belonged to an array of other groups – most of them more powerful than the two communist parties – ranging from the Trotskyite Workers’ Revolutionary Party to the governing MNR. The rigidly orthodox Monje added to Guevara’s frustrations, insisting that any revolution must be party led. He refused to recognize the authority of a commander who was not a card-carrying communist and prevented the Bolivian communists who trained in Cuba from joining Che’s group. The communists promised aid and support that they never had any intention of delivering, and they may have even provided the Bolivian authorities with information regarding Che’s whereabouts.Footnote 80

Ultimately, the Bolivian disaster demonstrated that Che’s model of guerrilla warfare, based on a selective reading of the Cuban experience, was not readily generalizable and that he neglected the unique aspects of the Cuban Revolution to his own peril.Footnote 81 In addition to discounting the key role urban revolutionaries played in the 26th of July Movement, Guevara’s overweening dedication to militant confrontation led him to eschew the sort of tactical compromises that Castro had pursued in order to broaden cooperation among the various anti-Batista elements. Most importantly, Guevara overestimated Bolivian popular revolutionary sentiment and ultimately failed to gain local support. Even though Barrientos had seized power via a military coup, he was then popularly elected in 1966 (albeit facing little opposition). He traveled extensively through Bolivia, giving speeches to the Indians in Aymara and Quechua and promising further economic and social programs. Che viewed these and earlier reforms as insufficiently radical, but many Bolivian workers and peasants disagreed. Most remained invested in their society and felt they had already experienced their revolution for national liberation under Víctor Paz. Ultimately, perhaps the fundamental ingredient missing from Che’s foco was that its cause was not viewed as just by the majority of Bolivians.

Furthermore, the response of the Barrientos regime to the presence of the guerrillas was highly effective. The Bolivian president requested the assistance of the CIA in the counterinsurgency campaign to eradicate Che’s foco but was still able to portray the campaign in a nationalist light because most members of Guevara’s group were Cuban and not Bolivian. He repeatedly drew attention to the foreign nature of the guerrilla movement and portrayed himself as a staunch defender of Bolivian law and order. In a deft move to appeal to Bolivia’s radical left, Barrientos even appointed four Marxists to his cabinet during the period of Che’s guerrilla activity in the country. Though he faced criticism from right-wing circles, he explained that he was not opposed to Marxists so long as they worked within the democratic process. With limited popular support, Guevara’s early success in battles against the Bolivian security forces gave way to months of frustration. On October 9, 1967, he was captured and executed by a Bolivian Ranger unit that had received counterinsurgency training from US Army Special Forces.Footnote 82

Aftermath and Legacies

Though there was a tremendous outpouring of grief among Latin America’s radical left, Che’s capture and execution were virtually ignored in Moscow. A brief Pravda obituary praised his “deep devotion to the cause of the revolutionary liberation of the peoples and great personal courage and fearlessness,” but the only public commemoration of Che’s life was a rally held by a small group of Latin American students from Moscow’s Patrice Lumumba People’s Friendship University.Footnote 83 Soviet news media continued to disparage the brand of revolutionary “adventurism” that Che exemplified, and a month after his execution, Brezhnev gave a speech in which he declared that socialist revolutions should only be launched in countries where the necessary objective conditions for revolution had already been fulfilled. The message was a clear reference to Che’s failure in Bolivia. Orthodox communist parties in Latin America followed suit, issuing denunciations of armed struggle and declaring their loyalty to the CPSU line.

The death of Che and the obliteration of the nascent Bolivian foco he had nurtured, combined with guerrilla defeats in Guatemala, Colombia, and Venezuela, contributed to an improvement in Cuba’s relations with the USSR. Though Castro continued to aid revolutionary movements, he was more selective in determining which ones to support. He continued to advocate the armed struggle but softened his rhetoric about the inevitability of violence.Footnote 84 By refusing to condemn the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, Castro signaled his support for Moscow’s foreign policy. Though his speech about the episode contained several veiled criticisms of the Soviets, it marked a turning point after which Soviet-Cuban relations were closer and less contentious. In 1972, Cuba became a member of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA), the Soviet-led economic assistance organization comprising the socialist bloc countries. Later in the year, a series of bilateral trade, economic, and financial agreements reshaped the Cuban economy along Soviet lines, eventually making the island’s economic dependence on Moscow almost total. Cuban officials now loyally defended Soviet policy positions in international organizations, especially the Non-Aligned Movement and the United Nations, but so too did the USSR become a key backer of Cuban support for Third World nationalism, actively aiding Castro’s support for communist governments in Angola and Ethiopia in the 1970s and 1980s.

Che’s radicalism and his fierce devotion to spreading the revolution would continue to inspire armed revolutionaries in Latin America, even after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the complete collapse of Soviet-style communism in Europe. Yet Che’s ideals and actions had exacerbated tensions in the Cuban-Soviet alliance and provoked the wrath of Washington. The ideological and theoretical hair-splitting that distinguished the Fidelistas from the Maoists from the pro-Soviet factions undermined the unity and cooperation necessary for effective action. The United States, unwilling to tolerate the rise of any leftist regime, happily took advantage of divisions by consolidating alliances with a range of Latin American dictatorships. The Pentagon designed and disseminated counterinsurgency tactics to stamp out the spreading influence of Fidelista and other Marxist-inspired guerrilla groups. The Vietnams that Che sought to inspire in South America failed as US counterinsurgency doctrine and training spread across the continent, culminating in Operation Condor, a transnational network of right-wing violence and oppression of the Marxist left.Footnote 85 In the United States, though some radical groups answered Che’s call (perhaps most infamously, the Weathermen), ultimately US society managed to cleave together in the maintenance of the status quo.Footnote 86

Nevertheless, the internationalism and solidarity that Che epitomized continue to animate Cuban foreign policy into the twenty-first century. Cuba provides humanitarian aid to dozens of countries in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Europe alongside emergency support, especially medical and health workers, to countries suffering from natural disasters. Thousands of students from all over the world received free medical education at the Latin American School of Medicine in Havana. Cuba even provided health care to children affected by the 1986 nuclear accident in Chernobyl.Footnote 87 Moreover, Che distinguished himself as an economic philosopher whose ideas shaped the Cuban economy and continue to inspire progressives worldwide. Many of the items on his agenda would appear in the 1970s in the guise of the New International Economic Order (NIEO), a political project aimed at enshrining the economic sovereignty of the postcolonial states. The major proponents of the program advocated a complete restructuring of global economic relations along lines similar to those Che sketched out at the 1961 Punta del Este conference.Footnote 88 The NIEO ultimately suffered the same fate as Che’s Tricontinental revolutionary vision. Both fell victim not only to the dominance of the industrialized capitalist world, headed by the United States, but also to the continuing appeal of nationalism and the enduring primacy of national interests.