Ika is a dialect of the Igbo language spoken in Ika South and Ika North East Local Government Areas of Delta State and the Igbanke area of Edo State in Nigeria. It belongs to the Niger Igbo cluster of dialects (Ikekeonwu Reference Ikekeonwu1986) spoken in areas bordering the west of the River Niger; Nwaozuzu (Reference Nwaozuzu2008) refers to these dialects as West Niger Group of Dialects. A word list of Ika, written by Williamson (Reference Williamson1968), was one of the earliest works on Ika and she points out in that work that Ika (and Ukwuani), though regarded as dialects of Igbo, are treated as separate on purely linguistic grounds. Ika phonology differs from that of Standard Igbo and other Igbo dialects and this is why the study of Ika has been of major interest to Igbo linguists in recent years. There have been moves to grant Ika a language status, as seen in the assignment of a unique reference code to Ika: the ISO language code for Ika is ISO 639–3 ikk while that for Igbo is ISO 639–3 ibo. Standard Igbo has the same consonants as Ika though the latter has two consonants, /ʃ/and/ʒ/, which do not exist in the Standard dialect. However, the vocalic system of Ika is largely different from that of Standard and some Igbo dialects which have eight vowels. Ika has a nine-vowel system which includes the schwa, which is a variant of some vowels. Furthermore, it has nine nasal vowels; Standard Igbo and other dialects of Igbo have no nasal vowels. Ika manifests intonation in addition to lexical tone. Standard Igbo and other Igbo dialects do not manifest intonation in the same way as Ika does; that is, they do not express attitudes and emotions through intonation. They manifest only lexical tone. In an earlier study of Northern Igbo dialects, Ikekeonwu (Reference Ikekeonwu1986) could only discover the existence of upstep in Abakaliki dialect. Okorji (Reference Okorji1991) and Egbeji (Reference Egbeji1999) have studied the intonation of Umuchu, an inland West dialect of Igbo. Their findings, particularly Egbeji’s, show that a declarative sentence can be changed to an interrogative one (repetitive question) by use of intonation. This is a syntactic function which can also be likened to what happens in Standard and most other Igbo dialects where the tone of the pronominal subject changes from high to low in the indication of interrogation. At present, therefore, there appears to be no evidence that attitudes and emotions can be expressed through intonation in Umuchu and other Igbo dialects as is observed in Ika.

Ikekeonwu (Reference Ikekeonwu1999) gives a vivid description of the Standard Igbo tone system; these tones also feature in Ika. Thus, Ika stands out as a dialect in which intonation and tone interact and this interaction affects the tonal realizations (see Uguru Reference Uguru2000).

Ika also stands out from other dialects in other respects. To show their differences, the future marker in Igbo and Ika are shown below in the translations ofthe English declarative sentence ‘I will go to the market’.

It can be observed that while in Standard Igbo, it immediately precedes the main verb in Ika the future marker is separated from the main verb.

Ika had been largely understudied but this is now changing. Uguru (Reference Uguru2004) discusses how intonation is used in narrative discourse,Uguru (Reference Uguru2005) discusses nasality in Ika, Uguru (Reference Uguru2006) deals with the relationship between intonation and meaning, and Uguru (Reference Uguru2007) discusses intonation variation and its acoustic effects.In 2010, the Holy Bible (New Testament) was translated into Ika. In writing this paper, the author, a fifty-year-old Ika female speaker read and recorded the Ika translation of the text ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ and the individual words used to exemplify the sounds of the dialect and the utterances illustrating the tone and intonation of the dialect. Phonemic transcription is what is mainly adopted in this Illustration.

Consonants

The infinitive form is marked by the prefix /í-/ and the tone on the first syllable of verb root is usually downstepped high, rarely low and never a full high tone. The phoneme /v/ is not commonly used in Ika except in ideophones and onomatopoeia.

Vowels

In Ika, there are nine oral vowels (in addition to the schwa, which acts like an allophone to some vowels) and nine nasal vowels. The schwa /ə/ does not have a phonemic status hence it is not included in the vowel chart. It is used here in the orthography because of want of proper letter to represent it. Using the letter representing the phoneme it replaced could be confusing.

Ika nasal vowels are indicated orthographically with word final alveolar nasal /n/, after the nasalized vowel (see Ika Bible Translation Committee 2010). Vowel nasality distinguishes minimal pairs in Ika (see Uguru Reference Uguru2005).

Vowel harmony is also a major feature in Ika.

The above chart explains the vowels that can co-occur in a word. However, the two vowels, /a/ and /ԑ/, which are in the intersection, can co-occur with both sets of vowels. Even when they occur in the verb root, they can trigger vowels from either set of vowels though they tend to attract [–ATR] vowels more than [+ATR] ones.

Ika has a predominantly CV syllable structure, that is, V, CV. This can be seen in such words as ọ /

![]() / ‘he/she/it’ and yụ /j

/ ‘he/she/it’ and yụ /j

![]() / ‘you (sg)’. However, there can be some rare cases of CVC structure, as seen in the word vàm ‘fast movement’. There are no consonant clusters in Ika.

/ ‘you (sg)’. However, there can be some rare cases of CVC structure, as seen in the word vàm ‘fast movement’. There are no consonant clusters in Ika.

Intonation system

Both tone (use of pitch variation in distinguishing words lexically or grammatically) and intonation (use of pitch variation mainly for expressing emotions and attitudes) feature in Ika. There are two major tones: high and low. The third, downstep, is not a major tone but a downstepped high.

Like in any tone language, tone distinguishes between words in Ika, as can be seen in the minimal sets below.

Negation is usually marked by the suffix /-nɪ/ and usually bears the downstep. Polarity is marked by a low-toned pronominal subject /ò/.

There are also six tunes (Uguru Reference Uguru2000). These are outlined below.

Intonation is one of the major features in which Ika phonology differs from many Igbo dialects. Intonation involves the use of to express various meanings, for example attitudinal and emotional, and to mark syntactic form. Also, in the use of intonation, an utterance has only one prominent syllable (the nuclear syllable). These two features are observed in Ika but not in the Standard or other Igbo dialects. Of major importance is that intonation distinguishes between declaratives and interrogatives except in wh-questions. Thus, an utterance could have six distinct attitudinal meanings depending on the tune the speaker chooses to use. The examples below show this for the utterance, Ḿbà ‘No’.

The difference between Ika Low Rise (LR) and Fall Rise (FR) can be appreciated more in the following utterances:

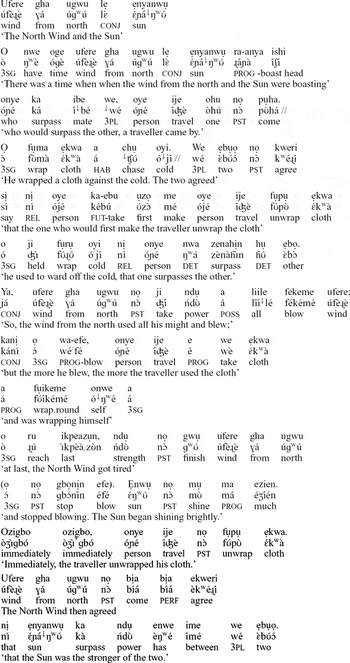

Transcription of recorded passage Ufere gha ugwu lẹ ẹnyanwụ ‘The North Wind and the Sun’

Annotations at syllable margins (rather than over vowels) indicate intonation while those over vowels mark tones. The tunes they represent are indicated in the translation. They are:

Orthographic version

Ufere gha ugwu lẹ ẹnyanwụ. O nwe oge ufere gha ugwu lẹ ẹnyanwụ ra-anya ishi onye ka ibe we, oye ije ohu nọ pụha. Ọ fụma ẹkwa achụ oyi. We ẹbụọ nọ kweri sị nị oye ka-ebu ụzọ me oye ije fụpụ ẹkwa o ji fụrụ oyi nị onye nwa zenahịn hụ ẹbọ. Ya, ufere gha ugwu nọ ji ndụ a liile fekeme ufere; kanị ọ wa-efe, onye ije ewe ẹkwa afụikeme onwe a o ru ikpeazụn, ndụ nọ gwụ ufere gha ugwu (ọ nọ gbọnịn efe). Ẹnwụ nọ mụma ezien. Ozigbo ozigbo, onye ije nọ fụpụ ẹkwa. Ufere gha ugwu nọ bịa bịa ekweri nị ẹnyanwụ ka ndụ enwe ime we ẹbụọ.

Interlinearized version

In this section, each segment consists of four lines: the first line is the original text in the orthographic form; the second line is the phonemic transcription, the third line is the interlinear gloss, and the fourth line is the English translation of the text.

Abbreviations

Acknowledgements

I wish to acknowledge all the people who have helped to make the publication of this paper possible. JIPA editors, reviewers and copy-editors have been of immense help in scrutinizing both the word and sound files. Queries about any slips or confusing issues should be directed to me, the author.