During the past few decades, there has been a worldwide decrease in undernutrition and a concomitant increase in overweight and obesity(Reference Black, Victora and Walker1–Reference Popkin3). These shifts occurred as a result of nutrition and epidemiological transitions. As a consequence, the burden of disease has shifted from primarily infectious and vector-transmitted diseases (associated with undernutrition) to non-communicable diseases such as type 2 diabetes and hypertension, which are associated with overweight and obesity(Reference Tzioumis and Adair4). Previous studies have found that as a country’s economy increases, so too does an urban lifestyle among its population, leading to reduced physical activity and increased consumption of energy-dense foods(Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng5). These factors help explain how populations can experience increases in overweight alongside persistent undernutrition(Reference Popkin3,Reference Popkin6–Reference Rivera-Dommarco, Barquera and González-Cossio8) , a situation that is fairly common for many countries in Latin America(Reference Rivera-Dommarco, Barquera and González-Cossio8–Reference Kosaka and Umezaki11).

Mexico has experienced a rapid and uneven nutrition transition. With economic growth, stunting prevalence has declined from 26·9% in 1988 to 13·6% in 2012(Reference Rivera-Dommarco, Cuevas-Nasu and González de Cosío12). Over the same time period, there was a 104% increase in the combined prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults, from 34·5% in 1988 to 71·2% in 2012(Reference Torres and Rojas13). However, these processes have not occurred in an even manner across Mexican states, regions(Reference Rivera-Dommarco, Cuevas-Nasu and González de Cosío12,Reference Gomez-Dantes, Fullman and Lamadrid-Figueroa14,Reference Rivera, Pedraza and Aburto15) or socio-economic groups(Reference Kroker-Lobos, Pedroza-Tobias and Pedraza16). Within this context, there has emerged a double-burden of malnutrition, frequently defined as households with both stunted children and overweight or obese mothers(Reference Tzioumis and Adair4,Reference Kroker-Lobos, Pedroza-Tobias and Pedraza16) . This coexistence poses challenges for health and nutrition policies as well as the healthcare system. For instance, widespread public programmes, such as conditional cash transfers that have been effective in reducing some forms of undernutrition, may have inadvertently contributed to obesity in some settings(Reference Fernald, Gertler and Hou17–Reference Shamah-Levy, Méndez-Gómez-Humarán and Gaona-Pineda20).

Prior research in Mexico has identified household characteristics such as living in the southern region and rural residence as well as maternal factors such as lower height, higher birth order, lower schooling and the presence of central maternal adiposity to be positively associated with child stunting(Reference Barquera, Peterson and Must21,Reference Shamah-Levy, Nasu and Moreno-Macias22) . The fact that over and undernutrition occur in the same household has given rise to the hypothesis that conditions that were once considered opposite sides of a plateau might actually share common causal factors such as a poor-quality diet(Reference Garrett and Ruel23), physical activity or aspects of the social and cultural environment(Reference Parra, Gomez and Iannotti24). Household food insecurity (HFI) (an indicator of poor household diet)(Reference Rodriguez, Mundo-Rosas and Mendez-Gomez-Humaran25) has been found to be positively associated with both childhood stunting(Reference Cuevas-Nasu, Rivera-Dommarco and Shamah-Levy26) and adult overweight(Reference Morales-Ruán, Méndez-Gómez Humarán and Shamah-Levy27). Additionally, severe HFI has been found to increase the risk of stunting in children with non-obese mothers, but not among whose mothers are obese(Reference Shamah-Levy, Mundo-Rosas and Morales-Ruan28).

Another potential shared causal factor between child stunting and maternal overweight is maternal height. In low- and middle-income countries, maternal height is inversely correlated with child stunting(Reference Özaltin, Hill and Subramanian29). Specifically, previous research carried out in Mexico found that as maternal height increases, the probability of having a stunted child decreases(Reference Shamah-Levy, Nasu and Moreno-Macias22). Evidence from Bangladesh, Indonesia and Guatemala suggests that short maternal height is associated with a higher risk of double-burden(Reference Lee, Houser and Must30,Reference Oddo, Rah and Semba31) . However, to our knowledge, no studies currently document such an association in Mexico.

In the current study, we construct mother–child dyads(Reference Parra, Gomez and Iannotti24,Reference Parra, Gomez and Iannotti32,Reference Parra, Iannotti and Gomez33) to assess the prevalence of different mutually exclusive groupings of mother and child nutritional status within the same household. These include: (1) households that have a stunted child and a non-overweight/obese mother (stunting-only); (2) those that have an overweight or obese mother but a non-stunted child (overweight-only); (3) those that have both a stunted child and an overweight or obese mother (double-burden) and (4) those with neither a stunted child nor an overweight or obese mother (neither-condition). We then test the association between short maternal stature and these different mother–child nutrition status groups, while controlling for important confounders.

The current study adds several insights to the literature. As discussed above, previous studies on double-burden in Mexico either consider HFI(Reference Shamah-Levy, Mundo-Rosas and Morales-Ruan28) or maternal height(Reference Fernald and Neufeld9,Reference Shamah-Levy, Nasu and Moreno-Macias22) as potential predictors of double-burden, but to our knowledge, our study is the first to consider both factors simultaneously. Additionally, we construct four mutually exclusive categories of household nutritional status using the mother–child dyad as the unit of analysis(Reference Tzioumis and Adair4) and employ multivariate statistical techniques to control for a number of important potential confounders.

Methods

Data source

We performed secondary data analysis using the 2012 National Health and Nutrition Survey, a two-stage probabilistic, national, rural, urban and state representative survey(Reference Gutiérrez, Rivera-Dommarco and Shamah-Levy34). Data were collected from 50 528 households across the 32 Mexican states between October 2011 and May 2012(Reference Romero-Martínez, Shamah-Levy and Franco-Núñez35).

Mother–child dyads are our unit of analysis. These dyads are commonly used when assessing weight discordance because it is assumed that mothers and children are in closer contact and share more resources than do other household members(Reference Tzioumis and Adair4). We excluded 333 households (3·1%) from the study because mothers did not live in the household, had died or were not otherwise identifiable, and 5405 women because they were not randomly selected for anthropometric measures. Dyads were constructed by matching children <5 years old to their non-pregnant mothers aged 12–49 years with anthropometric data (n 4764). The child’s age was reported by the mother and no woman surveyed within this age range had more than one surveyed child <5 years old. Finally, 58 dyads (1·1%) were excluded because of missing HFI data. This resulted in an analytic sample of 4706 mother–child dyads (see online supplementary material, Appendix 1).

Outcome variable

Child nutritional status

Stunting was assessed using height and age measurements. Height was assessed with a stadiometer with 1 mm precision(Reference Shamah-Levy, Rivera-Dommarco and Verónica36). Height-for-age Z-scores for children 0–59 months old were calculated according to WHO standards(37). The range of valid scores included in the dataset was between −6·0 sd and 6·0 sd(Reference Gutiérrez, Rivera-Dommarco and Shamah-Levy34). Children were categorised into stunted (height-for-age Z-scores ≤ 2sd) and non-stunted (height-for-age Z-scores ≥ −2 sd) according to WHO cut-off points(38).

Maternal nutritional status

BMI of participants (kg/cm2) was assessed using height and weight. Weight was assessed using a SECA scale with 100 g precision and height with a stadiometer of 1 mm precision(Reference Shamah-Levy, Rivera-Dommarco and Verónica36). For adolescent women (13–19 years old) BMI-for-age Z-scores were calculated using WHO standards(Reference de Onis, Onyango and Borghi39). BMI values outside the range of 10–58 were excluded from the primary data source. Adolescents with Z-scores above +1 sd and below +2 sd were classified as overweight and those with Z-scores above +2 sd were classified as obese. Based on their BMI, women 20–49 years of age were classified into the following categories: underweight: BMI 10–18·49, normal weight: 18·5–24·99, overweight: 25–29·99 and obese ≥ 30(40). Mothers classified as overweight or obese were assigned a 1 or 0 otherwise.

Household nutrition status/types of mother–child dyad

Based on the nutritional status of the child and the mother, households were classified into four outcome categories:

-

Households with a stunted child and non-overweight/obese mother were classified as stunting-only.

-

Households with a non-stunted child and overweight/obese mother were classified as overweight-only.

-

Households that had both a stunted child and an overweight or obese mother were classified as double-burden.

-

Households that had neither a stunted child nor an overweight/obese mother were classified as neither-condition. This category was used as the reference group in multivariate analyses.

Independent variable

Maternal height was available as the mother’s height in cm. It was operationalised as a dichotomous variable. Consistent with previous studies, a value of 1 was assigned to mothers with height <150 cm, considered to be ‘short stature’ in the Mexican population(Reference Shamah-Levy, Nasu and Moreno-Macias22). A value of 0 was assigned otherwise.

Control variables

HFI was assessed using The Latin American and Caribbean Food Security Scale(41). This scale uses fifteen questions to measure the perceptions of food access during the past 3 months that result from the availability of household resources. It uses dichotomous questions to inquire on the perceptions of worry, quality and quantity of available foods. Positive response options were assigned a value of 1 and 0 otherwise. The total summation score allowed us to generate a categorical assessment of HFI using pre-established cut-off values(41). Households with no positive answers (score of 0) were considered food secure. Households with members under 18 years of age and 1–5 positive answers or without members under 18 years and a score between 1 and 3 were considered to have mild food insecurity. Households were classified as moderately food insecure when they had scores between 6 and 10 and members under 18 years of age, and 4–6 positive answers without members under 18 years old. Severely food insecure households were those with members with 18 years and a score between 11 and 15, and those without members under 18 years and 7–8 positive answers(41) (see online supplementary material, Appendix 2). To assess socio-economic status (SES), we used a pre-constructed measure of well-being based on household characteristics including household demographic structure, head of household characteristics, infrastructure conditions, household assets, consumption patterns and marginality level. The National Health and Nutrition Survey 2012 team used principal component analysis on the list of items and divided the resulting principal factor into quintiles(Reference Gutiérrez42). Quintile 1 (Q1) represents the lowest (poorest) and Quintile 5 (Q5) the highest possible level of SES. A dichotomous variable was used to control for exposure to urban environments. Urban localities were those with ≥2500 inhabitants and assigned a 1, and rural localities with <2500 inhabitants were assigned a 0, as provided by the primary data source. In order to control for regional variation, states were classified into four regions: South, North, Centre and Mexico City (classified as a region of its own due to population density)(Reference Gutiérrez, Rivera-Dommarco and Shamah-Levy34). Maternal age was operationalised into three categories: 13–19, 20–35 and 36–49 years.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using Stata version 14·2(43) and used the SVY command to incorporate sampling weights and adjust for complex survey design effects. We obtained means for continuous variables, proportions (%) for categorical variables and linearised se for both. First, we analysed the entire sample and then we stratified results by type of mother–child dyad. Then, we performed bivariate analysis to assess overall statistical differences between categories of household nutrition status using design-corrected F tests and adjusted Wald tests to determine statistical significance.

For multivariate analyses, we used a multinomial logistic model (mlogit) to assess the probability of having stunting-only, overweight-only and double-burden and compared with those where neither-condition was observed. We first estimated relative risk ratios (RRR) for maternal short stature (ref = non-short stature) with 95% CI adjusting for SES, locality type, maternal age and region. Additionally, we estimated the predicted probability of each outcome category for households with and without maternal short stature as well as the marginal effect (marginal effect at representative values)(Reference Long and Freese44). Both of these calculations adjusted for the same covariates in the RRR estimation. To test hypotheses, we used two-sided tests and P < 0·05 in all statistical analyses.

Results

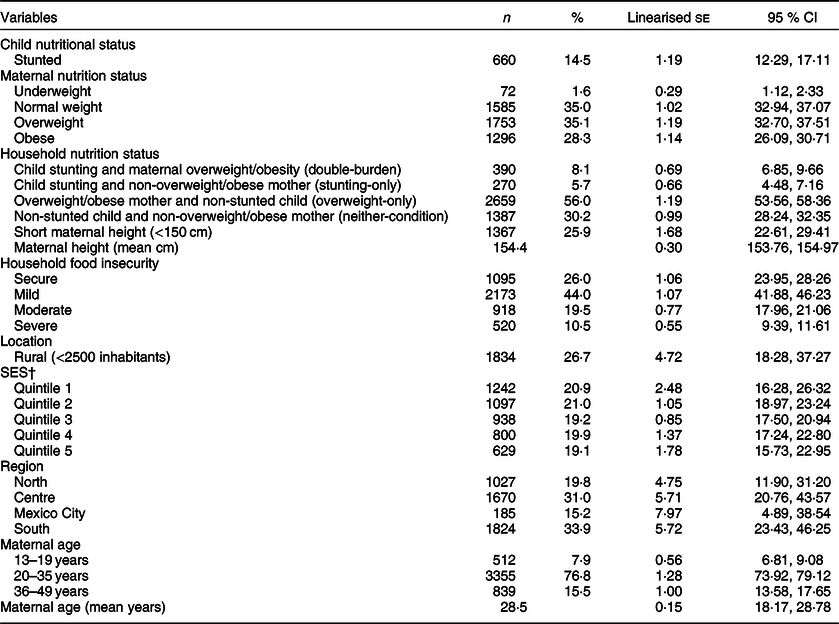

Out of the entire sample, 14·5% of children were stunted while 63·4% of mothers were overweight or obese. We found that 390 (8·1%) households were double-burden, 5·7% were stunting-only, more than half were overweight-only (56·0%) and 30·2% had neither-condition. The mean maternal height was 154 cm (with a se of 0·30) and 25·9% of the mothers had short stature. Mildly food insecure households were most common, representing 44·0% of households, while severe HFI households were the less frequent (10·5%). Mother–child dyads were evenly distributed across SES categories and concentrated in the Southern and Central regions (33·9 and 31·0%, respectively). Mean maternal age was 28 years and there were < 10% of adolescent mothers (Table 1).

Table 1 Nutritional status, socio-economic, demographic characteristics and nutritional status of the sample (n 4706)*

SES, socio-economic status.

* Used weighted data to adjust for the complex design of the survey.

† Quintile 1 is the lowest and Quintile 5 the highest level of SES.

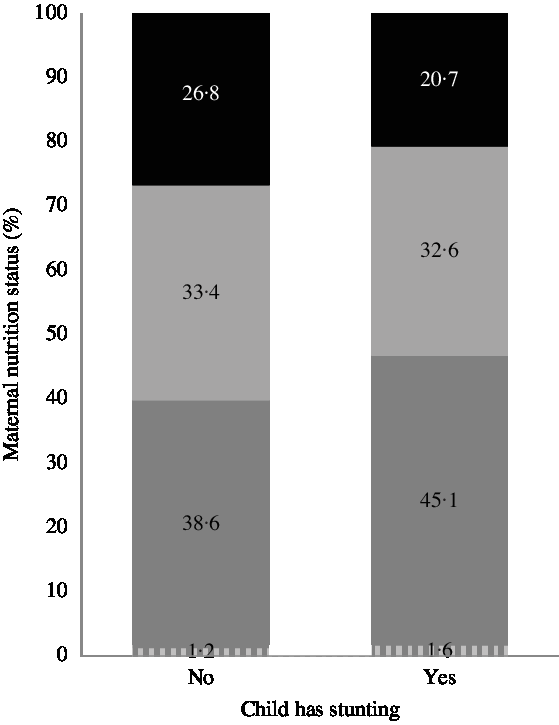

More than half of the children with stunting had an overweight or obese mother (53·3%). Of the remaining children with stunting, 1·6% had underweight mothers and 45·1% had mothers in the normal weight category. Children who were not stunted had a higher proportion of overweight or obese mothers (60·2%) and a lower proportion of normal or underweight ones (38·6 and 1·2%, respectively) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Child and maternal nutrition status. ![]() , Obesity;

, Obesity; ![]() , Overweight;

, Overweight; ![]() , Normal weight;

, Normal weight; ![]() , Low weight

, Low weight

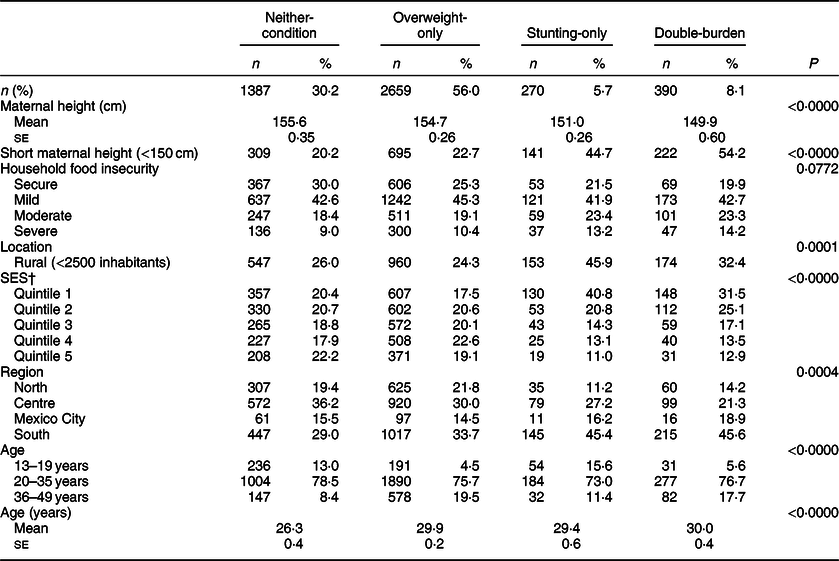

Stratified results show statistically significant differences across mother–child dyad types in mean maternal stature, proportion of mothers with short maternal height, locality type, SES, region and maternal age. Mothers in double-burden households had the lowest mean stature (149·9 cm) while those with neither-condition had the highest (155·6 cm). Double-burden households had the highest proportion of mothers with short stature (54·2%), followed by stunting-only households (44·7%), overweight-only (22·7%) and neither-condition households (20·2%). We also observed that double-burden and stunting-only households were mostly located in rural localities (32·4 and 45·9%, respectively), while overweight-only (24·3%) and neither-condition were not (26·0%). Regarding SES, neither-condition and overweight-only were equally distributed across quintiles, while stunting-only households and double-burden ones were mostly poorer and concentrated in Q1 and Q2 (70% of stunting-only were in Q1 and Q2, and about 50% of double-burden households were in these categories). In terms of regional distribution, double-burden (45·6%) and stunting-only (45·4%) had the highest concentration of pairs in the South, while neither-condition households were concentrated in the Centre (36·2%). Mothers in neither-condition households were younger (26 years) than those in overweight-only, stunting-only or double-burden ones (29 and 30 years) (Table 2).

Table 2 Nutritional status, socio-economic and demographic characteristics by type of mother–child dyad (n 4706)*

SES, socio-economic status.

* Used weighted data to adjust for the complex design of the survey. Significance was assessed with two-sided P < 0·05.

† Quintile 1 is the lowest and Quintile 5 the highest level of SES.

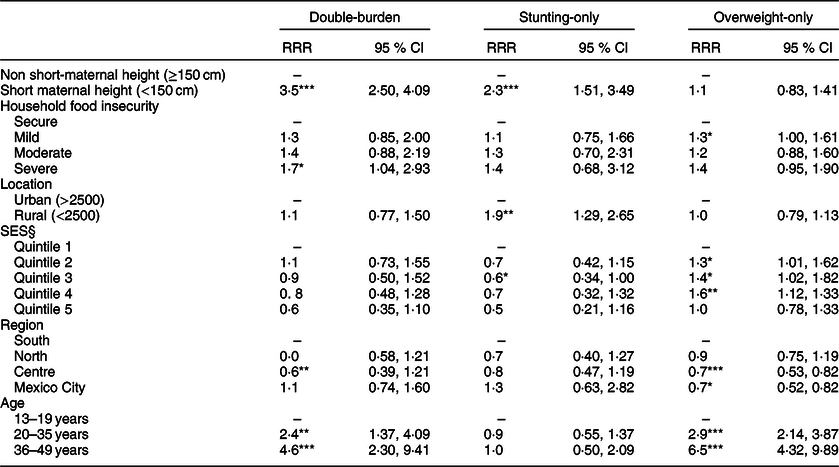

Our multivariate analyses show that maternal short stature (RRR = 3·5; 95% CI 2·50, 4·09) and severe HFI (RRR = 1·7; 95% CI 1·04, 2·93) were positively associated with double-burden, and that households in the Central region were less likely to develop double-burden than those in the South (RRR = 0·6; 95% CI 0·39, 1·21). Our results also show that the relative risk of having double-burden significantly increases with maternal age (Table 3).

Table 3 Relative risk ratios (RRR) and 95% CI of the factors associated to households with child stunting and maternal overweight (double-burden), households with child stunting and non-maternal overweight/obesity (stunting-only), households with a non-stunted child and maternal overweight/obesity (overweight-only) compared with households with a non-stunted child and a non-overweight/obese mother (neither-condition) (n 4706)† ‡

RRR, relative risk ratio; SES, socio-economic status.

† Showing adjusted RRR with 95% CI in parentheses from multinomial logistic regression model comparing double-burden, stunting-only and overweight-only households to those with neither-condition.

‡ Used weighted data to adjust for the complex design of the survey.

§ Quintile 1 is the lowest and Quintile 5 the highest level of SES.

*P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

Additionally, the relative risk of stunting-only was positively associated with the presence of maternal short stature (RRR = 2·3; 95% CI 1·51; 3·49) and rural residence (RRR = 1·9; 95% CI 1·29, 2·65). SES was negatively associated with stunting-only (RRR = 0·6; 95% CI 0·34, 1·00). It should be noted that rounding of the CI leads to an upper limit of 1·00, meaning that the association between SES and the presence of a stunted child with a non-overweight/obese mother is fairly small in magnitude. We found that households with mild HFI are more likely to have overweight-only (RRR = 1·3; 95% CI 1·00, 1·61) and so are those in higher SES quintiles (RRR = 1·6; 95% CI 1·12, 1·33). Also, dyads in the Central region and Mexico City are less likely to be overweight-only than those in the South (RRR = 0·7; 95% CI 0·53, 0·62 and RRR = 0·7; 95% CI 0·52, 0·82). Results also show that the RRR of overweight-only increases with maternal age (Table 3).

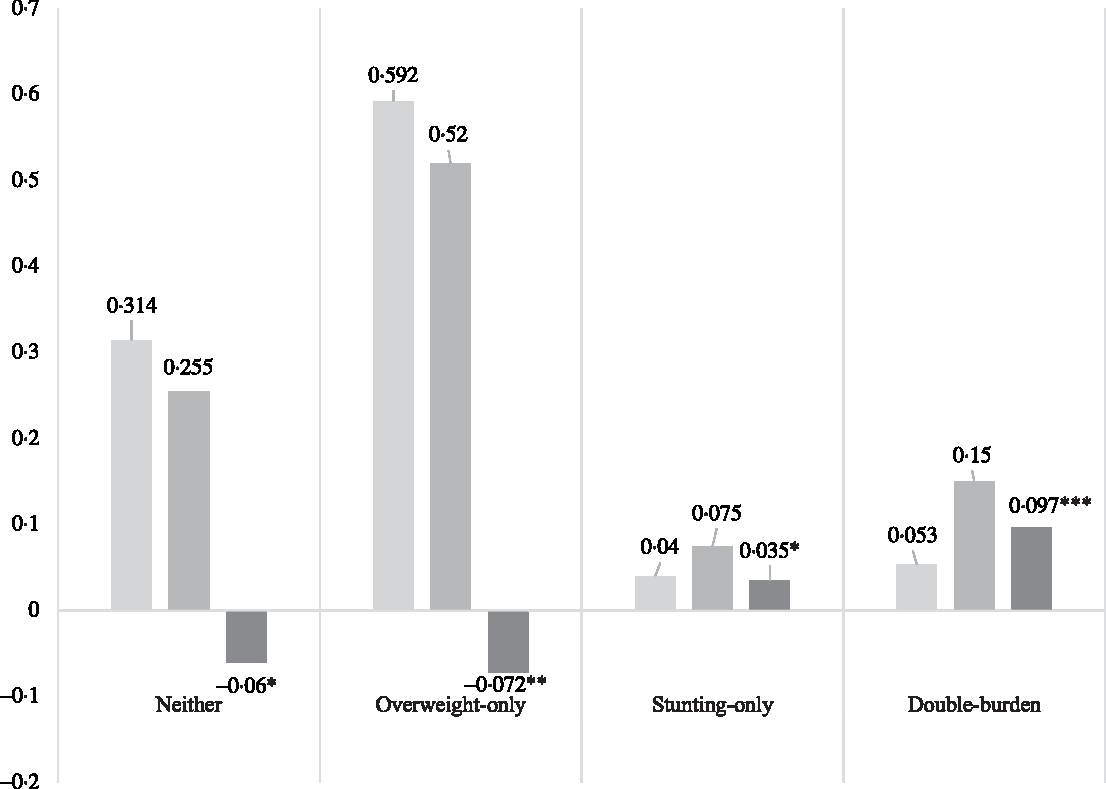

Having maternal short stature significantly increases a household’s probability of double-burden from 0·053 to 0·150, a change of 9·7 % points (p.p.) (P < 0·001) and from 0·04 to 0·075 (P = 0·019), a change of 0·035 in stunting-only households. We observed an inverse association between short maternal height and overweight-only and neither-condition households, where the probability of these outcomes was higher for women who did not have short stature (an absolute change of −7·2 and −6·0 p.p., respectively) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Predicted probabilities and marginal effect of maternal short stature on mother–child dyad nutrition status. Used weighted data to adjust for the complex design of the survey; *P < 0·05; ** P < 0·01; *** P < 0·001. ![]() , No short stature;

, No short stature; ![]() , Short stature;

, Short stature; ![]() , Absolute change

, Absolute change

Discussion

The current study estimated the prevalence of double-burden – households with child stunting and maternal overweight or obesity – and assessed whether mothers in double-burden households were more likely to be of short stature. Our results are consistent with previous estimations: the prevalence of double-burden households in Mexico was above 8%(Reference Kroker-Lobos, Pedroza-Tobias and Pedraza16), and the prevalence of households that have maternal overweight but not child stunting was greater than that of households without either condition.

The prevalence of double-burden households in Mexico was below than the prevalence of this phenomenon in lower middle-income Latin American countries such as Guatemala(Reference Lee, Houser and Must30,Reference Ramirez-Zea, Kroker-Lobos and Close-Fernandez45,Reference Doak, Campos Ponce and Vossenaar46) , Ecuador(Reference Freire, Silva-Jaramillo and Ramirez-Luzuriaga47) and Honduras(Reference Dieffenbach and Stein48), but was higher than in higher middle-income Latin American countries such as Colombia(Reference Parra, Gomez and Iannotti24,Reference Sarmiento, Parra and Gonzalez49) , Brazil(Reference Gubert, Spaniol and Segall-Correa50,Reference Gea-Horta, Silva Rde and Fiaccone51) and Peru(Reference Dieffenbach and Stein48). This could be due to the widespread prevalence of adult overweight and obesity in Mexico (63·4% of mothers in our sample), while < 6% of households were stunting-only. Overweight-only households were observed evenly across SES levels, while stunting-only households were found almost exclusively in the lowest SES levels and in rural localities.

Another major finding is that more than half of the children (53%) with stunting had an overweight or obese mother. Of the remaining 47% of stunted children, < 2% had mothers with low weight and 45% were in the normal weight category. A possible explanation for this result is that low weight households tend to have income that is insufficient to increase their BMI(Reference Fernald and Neufeld9), while the normal weight group might be at-risk of becoming overweight. Even though formal forecasting is beyond the scope of this paper, it is possible that if increasing adult overweight trends(Reference Pedroza and Rivera-Dommarco52) continue, all children with stunting could have overweight or obese mothers and therefore live in double-burden households. This situation merits further exploration and should be monitored.

Short maternal height was observed in 25% of our sample, in more than half of double-burden households and 45% of stunting-only households. Moreover, results from our multinomial logistic regression showed that in households with short maternal height, the likelihood of having stunting-only is twice than that of having neither-condition, consistent with previous studies in Mexico(Reference Fernald and Neufeld9,Reference Shamah-Levy, Nasu and Moreno-Macias22) . Specifically, there is a 3·5 p.p. (P-value = 0·019) difference of being stunting-only between households with and without maternal short stature. More importantly, the risk of double-burden increases by 9·7 p.p. (P-value <0·000) when the mother’s height is below 150 cm. The opposite association is observed for households that are overweight-only, where maternal short stature decreases the probability of overweight-only by 7·2 p.p. (P-value = 0·007) and of having neither-condition by 6%p.p. (P-value = 0·014). Having short height not only puts the mother at higher risk of overweight or obesity but also her child at higher risk of stunting. This is consistent with prior studies which have found that maternal short stature increases the risk of double-burden in Indonesia(Reference Oddo, Rah and Semba31), Guatemala(Reference Lee, Houser and Must30,Reference Doak, Campos Ponce and Vossenaar46) and Brazil(Reference Gea-Horta, Silva Rde and Fiaccone51).

A possible explanation for our findings can be found in a growing body of literature which supports that maternal short stature has adverse short- and long-term consequences on child development. For example, in some low- and middle-income countries, maternal short stature has been negatively associated with small-for-gestational-age, preterm births(Reference Kozuki, Katz and Lee53), child growth patterns(Reference Özaltin, Hill and Subramanian29,Reference Addo, Stein and Fall54,Reference Ali, Saaka and Adams55) and increased risk of infant mortality(Reference Özaltin, Hill and Subramanian29). Additionally, prior studies have identified that child undernutrition during the first years has an important influence on adult health outcomes such as obesity and non-communicable diseases(Reference Black, Victora and Walker1,Reference Beltrán-Sánchez, Crimmins and Teruel56) and that individuals with poor fetal growth or stunting in the first years of life are more likely to gain excessive weight during adolescence, placing them at higher risk of nutrition-related diseases(Reference Victora, Adair and Fall57). Furthermore, poor nutrition in early childhood could be an important driving factor behind obesity in low- and middle-income countries(Reference Abdullah10,Reference Victora, Adair and Fall57) . In that vein, within a dyadic context, maternal height becomes a significant predictor of maternal and child nutritional status, possibly reflecting the transmission of disease burden acquired by the mother during her early childhood.

Our results underline the importance of continuing to invest in prenatal care and early childhood development in order to improve health and well-being across the life course. Since experiences during the first years of life can lead to negative health outcomes and affect future generations, early childhood investments could be cost-effective alternatives to address adult outcomes(Reference Victora, Adair and Fall57–Reference Richter, Daelmans and Lombardi59).

In contrast with existing evidence from some Latin American countries(Reference Parra, Gomez and Iannotti32), our study shows that factors such as exposure to urban lifestyles and SES are not predictors of double-burden in Mexico, but do predict child stunting (without an overweight/obese mother). This could be because Mexico is at an advanced stage of an uneven health transition(Reference Gomez-Dantes, Fullman and Lamadrid-Figueroa14,Reference Kroker-Lobos, Pedroza-Tobias and Pedraza16) leading to a situation in which stunting-only households are concentrated in lower socio-economic strata, double-burden households are found in both urban and rural localities, overweight-only households are spread across the country and there is a higher proportion of neither-condition households in the Central region.

According to our results, HFI is a predictor of double-burden and overweight-only but not of stunting-only. We found a weak but statistically significant relationship between severe HFI and double-burden, consistent with other studies that have explored this association(Reference Gubert, Spaniol and Segall-Correa50). The weakness of this association could be due to the fact that both HFI and maternal overweight are widely spread across the country and that the causal pathways that explain nutrition status are highly complex. Nevertheless, there is evidence to support that HFI may be a shared factor in the causal pathways of child undernutrition and maternal overweight, indicating poor dietary quality(Reference Garrett and Ruel23,Reference Parra, Gomez and Iannotti24,Reference Jones, Mundo-Rosas and Cantoral60) . Our results diverge from those obtained in a previous study(Reference Shamah-Levy, Mundo-Rosas and Morales-Ruan28), where severe HFI increased the risk of stunting-only households but not of double-burden, these differences could be due to the fact that we included different variables in our models and a different analytic strategy.

Households with a stunted child but not an overweight or obese mother and those with double-burden share socio-demographic characteristics such as being concentrated in the lowest socio-economic quintiles, in the Southern region and in rural localities. Both conditions are also associated with short maternal height. These types of households are significantly different from maternal overweight-only households and those that have neither-condition, both of which are more evenly distributed across SES quintiles, in urban localities, in the Central region and have fewer mothers with short stature.

One of the limitations of our study is that by using cross-sectional data, we are unable to assess the direction of the association between some covariates such as HFI, SES and nutrition status, leading to possible reverse causality. The need for longitudinal studies to disentangle the complexity of these relationships has previously been acknowledged(Reference Kosaka and Umezaki11). Ideally, information on the mother’s early childhood environment would allow for assessing its effect on her adult outcomes and those of her children. However, even with data taken at only one time point, we are able to measure the significance of maternal height as a predictor of maternal and child nutrition status, potentially reflecting the transmission of nutrition and health conditions from one generation to another. In addition, our operationalisation of household nutrition status combined overweight and obese mothers. This should be taken with caution because there might be specific issues in the extremes of the BMI distribution(Reference Razak, Corsi and Slutsky61) and overweight and obesity might have different risk factors and effects.

Another limitation is that we do not account for the role played by nutrition and health policies in the development of child stunting and maternal overweight/obesity. As identified in previous studies, health and nutrition programmes originally devised to target undernutrition could be contributing to the development of overweight or obesity. For example, in the case of Mexico’s conditional cash transfers, doubling the cash transfer was associated with better motor development and nutrition among children(Reference Fernald, Gertler and Neufeld62), but to a higher BMI, diastolic blood pressure and overweight among adults(Reference Fernald, Gertler and Hou17). More recent studies found that cash and in-kind transfers not only increase fruit, vegetable and micronutrient consumption but also lead to excess energy consumption(Reference Leroy, Gadsden and Rodríguez-Ramírez18). In that vein, our findings continue to draw attention to the challenges set by the double-burden of malnutrition for public programmes that seek to improve health and nutrition, which has been pointed out in existing literature(Reference Fernald63).

It is also important to highlight that studies seeking to understand the drivers of the double-burden of malnutrition may operationalise this outcome in different ways, defining it as the coexistence of maternal adiposity and child stunting(Reference Barquera, Peterson and Must21), overweight and anaemia(Reference Jones, Mundo-Rosas and Cantoral60), child overweight with concurrent stunting(Reference Fernald and Neufeld9,Reference Bates, Gjonca and Leone64) and at least one household member with overweight and one with underweight(Reference Doak65). Each measurement poses different challenges and can yield different results. Our findings highlight the complexities of the relationships between undernutrition, overweight and their associated factors in a country in an advanced stage of the nutrition transition that has experienced economic growth while widening inequality gaps(Reference Fernald and Neufeld9,Reference Gomez-Dantes, Fullman and Lamadrid-Figueroa14,Reference Kroker-Lobos, Pedroza-Tobias and Pedraza16) .

Conclusions

Maternal overweight and HFI are generalised population issues in Mexico, where six out of ten women between 13 and 49 years of age are overweight or obese and only three in ten households are food secure. Additionally, over 50% of children who are stunted have a mother who is overweight or obese. It is possible that at least 20% of the remaining mothers will develop either of these conditions over the next few years. Women who are short stature are more likely to be overweight and have a stunted child than those who are not short-statured. These findings underline the challenges faced by public healthcare systems, which have to tend to a population with multiple forms of malnutrition. These difficulties are also faced by public programmes targeting undernutrition, which must develop strategies to prevent unhealthy weight gain among their beneficiary population.

The significance of maternal height as a predictor of maternal overweight and childhood stunting highlights the importance of devising policies that focus on the quality of prenatal care and early childhood development, for they might represent a cost-effective way of preventing child undernutrition and later adverse health outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: None. Financial support: L.F.B. received support from the Graduate Research Summer Mentorship program from the UCLA Graduate Division to conduct part of this research. This research did not receive any other support from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: L.F.B. conceived the article, developed the conceptual model analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. J.M. drafted and critically revised the manuscript, R.K. interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: We performed secondary analysis using a survey for which respondents provided written consent after being notified of the survey’s purpose.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898002000292X